5. Share-Based Compensation Plans

Aims and objectives of this chapter

• Explain all accounting and finance issues in share-based compensation

• Explain stock award plans

• Discuss the evolution of SFAS 123(R)

• Explain the accounting for restricted stock awards

• Discuss stock option expensing

• Discuss the debate on stock option expensing

• Explain the accounting for stock options

• Discuss stock plans with contingencies

• Explain tax implications of stock plans

• Discuss the APIC pool and deferred tax assets as they relate to stock option plans

• Explain the international tax implications of share-based employee compensation plans

• Discuss the differences between IFRS and GAAP in employee stock option accounting

• Discuss stock purchase plans

• Discuss stock appreciation rights

• Demonstrate the accounting for stock appreciation rights

A current common compensation practice is to include a share-based equity compensation plan as part of the total compensation package. The practice has been prevalent as part of an executive or senior management compensation programs, but now many companies around the world are including a share-based component in their total compensation package.

High-tech companies use these plans for all categories of employees. And if not for all employees, these companies use share-based plans to attract and retain key technical employees. Technical employees are the source of intellectual capital that high-tech companies need to succeed. Share-based plans are also almost always used to compensate outside board of directors.

Companies use share-based plans as a major component of the total compensation package because these plans motivate plan participants to act in the best interest of all shareholders.

The fact that the use of share-based plans is increasing is evidenced by the growth of professional organizations such as Global Equity Organization1 and National Center for Employee Ownership.2

Share-based compensation plans have many dimensions covering eligibility, amounts of the grant, competitive practices, ownership culture, legal, tax, accounting, dilution (overhang), under-water options, and repricing of options. This chapter analyzes the accounting and finance issues that affect share-based compensation plans.

Share-based plans can consist of outright grants of shares, stock options, stock purchase plans, stock appreciation rights, or even cash payments tied to the market price of shares (phantom stock plans). Although the structure of these plans varies, the goal is the same: to compensate employees based on performance incentives. The accounting goals are also common across all plans: to establish a fair value of the compensation and to spread the calculated compensation value over the term of the receiving employee’s service period.

Stock option expenses can be quite significant. After all, CEOs often hold stock options or stock grants with a value that is between 30 to 50 times their cash compensation. In addition, it has become common practice to distribute stock options and stock grants to a large percentage of the employee population, thus increasing stock option expenses.

Stock Award Plans

Ever since the Federal Accounting Standards Board (FASB) issued its FAS 123 regulation, which now requires expensing of stock plans, companies have been adopting stock award plans. Award plans are grants of shares of stock subject to certain conditions. The conditions are normally called restrictions, and that is why these award programs are called restricted stock awards.

The restrictions are usually tied to continued employment for some pre-determined period. An employment restriction may state that if the employee terminates voluntarily or is terminated by the firm before the predetermined period ends, the shares awarded can be forfeited. The employee cannot sell the shares during the restriction period. The restrictions are designed to motivate the employee to stay with the company for a certain period of time or even motivate the employee to achieve certain preset performance goals.

On the grant date, the shares are transferred to employees subject to an agreement that the employee cannot sell, transfer, or pledge the shares until vesting occurs, which means until the employee earns these shares by way of removing the restrictions imposed. The shares can be forfeited if the restrictions are not satisfied. The company might retain the physical possession of the shares during the restriction period. The employee can be given all the rights of a shareholder subject to the restrictions and forfeiture requirements.

Advantages of restricted stock plans include the following:

• Restricted stock does not become worthless. No matter what happens to the market price of the underlining shares, the restricted stock retains some value.

• With restricted stock, dilution of current shareholder, interests is less of an issue as compared to stock options. In restricted stock plans, the number of shares granted is not as large as that granted in stock option plans. The reason for the lower number is that at the end of the vesting period the shares granted will have some value whereas under stock option plans the shares awarded might not have any value. In other words, the stock option values might be “under water” if the market price of a stock goes below the exercise price.

• Restricted stock plans align employee incentives better with the company’s objectives. Often, the holder of restricted stock is also a shareholder, resulting in a better alignment with the long-term objectives of the company.

The compensation expense amount connected with a restricted stock is the market price of regular stock being traded on the date the restricted stock was granted. This amount is accrued as a compensation expense over the service period for which participants receive the shares, usually from the time the restricted stock is granted until the time the restrictions lapse or the restrictions are lifted. Once the restrictions are lifted, paid-in capital in restricted stock is replaced by common stock and paid-in capital in excess of par. The compensation expense is calculated on the date the grant is made, and the valued is based on the market price of the stock on that date. Market-price changes that happen after the grant date do not affect the restricted stock valuation.

For restricted stock plans, most companies base vesting on continued employment for a period of three to five years. Some companies might base vesting on some performance criteria, such as revenue, net income, or operating cash flows. Or the criteria can be a combination of various financial metrics. If the stock is a dividend-yielding stock, the participant collects the dividends, but those dividends can be forfeited if the participant terminates employment before the stipulated vesting date.3

3 Kiesco, D.E., Weygandt, J.J., Warfield, T.D., Intermediate Accounting, 13e., Wiley, 2010.

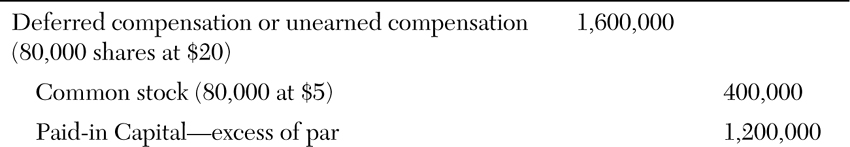

Accounting for Restricted Stock Awards

Let’s assume that on January 1, 2013, Zentec Corporation granted a restricted stock award of 80,000 shares with a term of four years, expiring on December 31, 2016, to four of its executives at 20,000 shares each. Shares have a current market price of $20 per share. The service period is four years. Vesting for the four executives occurs if they stay with the company for the entire four-year term. The par value of the shares granted is $5 per share for the restricted stock grant.

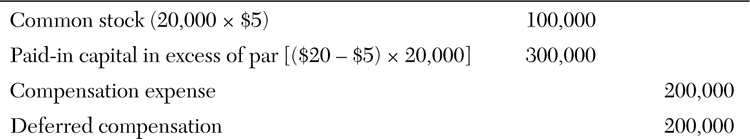

Zentec makes the journal entry shown in Exhibit 5-1 on the date of the grant.

The credit entry of common stock and paid-in capital in excess of par indicates that stock has been issued. The debit entry of unearned compensation or deferred compensation is entered as a contra-equity account in the equity section of the balance sheet. This amount indicates that the company will recognize a compensation expense for each of the four years. Unearned compensation is a cost of service that has not been performed as yet. Therefore, it is not an asset.

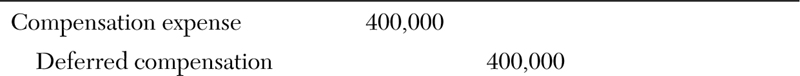

At the end of each year 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016 (on December 31 of each year), Zentec will enter a compensation expense for that year. For example, for 2013 the entry is as shown in Exhibit 5-2.

Note: $100,000 for each executive; $400,000 for 4 executives

If any of the four executives leave before the four-year period ends, he or she will forfeit rights to the shares and Zentec will reverse the accounting entries already recorded. For example, suppose that one executive leaves on April 3, 2015. No expense has been recognized for 2015 as yet. The reversing entry is as shown in Exhibit 5-3.

Note: $400,000 applies to one executive for the entire grant

Zentec reverses the compensation expense of $200,000 recorded through 2013. Also, it debits common stock and paid-in capital in excess of par, in recognition of the forfeiture. Zentec also credits unearned compensation for the next 2 years, because of the termination of the one executive.

In the restricted stock plan, vesting did not occur at all for the executives so nothing was earned out. Therefore, reversal entries need to be made. One executive left before the continued employment requirement was met. Therefore, that executive’s stock grant was forfeited.

Restricted stock plans have many advantages, not the least of which is the relative simplicity of the accounting just demonstrated. So because of the accounting, simplicity, and lower-per-unit grants, restricted stock has fast become a very attractive equity compensation element.

Stock Option Plans

In stock award programs, grants of stock are made, whereas in stock option programs, an option to purchase a stock is granted to participating employees. Over the past 40 years, stock option programs have become an integral part of the total compensation package for senior managers, executives, and key employees.4 Although used first in the United States, companies across the globe stock now use option plans.

4 A survey published in AICPA’s Accounting Trends and Techniques, 2007, reported that of 600 companies, 590 companies stated that they had stock option plans.

The accounting objective for stock option plans is to recognize an expense for these plans over the employment period of the employee who was awarded options under a stock option plan.

Options have been a controversial feature of the total compensation strategy. This is because stock options have made many CEOs exceptionally wealthy. Stock options have been legendary in the high-technology industry. There have also been various cases of malpractice with option-price backdating and grant amounts that defied logic. These factors have led to a great deal of scrutiny from various governmental agencies and resulted in these plans being immersed in tax and legal issues. (Note that this chapter focuses solely on the accounting issues related to stock option plans.)

Fundamentally, stock options give employees the option to purchase stock at (1) a specified exercise price (normally the market price on the date of the grant), (2) a predetermined period of time for vesting the option granted and for exercising the option, and (3) with a specified time for the contract period (option term).

The Stock Option Expensing Debate

The debate has been about what monetary value should be assigned to these options for expensing purposes. So, the controversy has been around how to measure the value of these options. Note that this form of compensation is noncash compensation.

In the past, options were valued (and not reported on the income statement, but rather were explained in footnotes to the financial statements) at their intrinsic value. That means, let’s say, an option was granted at an exercise price of $10, but the market price on the date of the grant was $15. So, the option had an intrinsic value of $5. But, usually, options were granted at an exercise price that was the same as the market price on the date of the grant. Therefore, the option actually had a zero intrinsic value and as such there was no expense to be recognized. Before the stock option expensing regulation (FAS 123(R)) was promulgated, zero intrinsic valuation was assumed for expensing purposes even though the real value of these options could have been in the millions of dollars. This led a lot of people to start questioning the logic of recognizing zero expense when stock options were an integral part of an executives’ compensation and indeed had value. In the absence of expense recognition, executives were raking in large sums of money when they exercised and sold their options. Although there is no cash impact for the company when it comes to the valuation of stock option plans, there is an implied expense involved. Because of the noncash nature of this implied expense, stock option expensing has been a matter of much debate.

Prior to 1993, stock options were being valued under the intrinsic value method under APB opinion 25. The FASB had been wavering all over on what standards for option expensing would be appropriate (the “right” way to determine the fair value of stock options). In 1993, the FASB issued a standard that would have required a fair value measurement process, but these standards were met with a lot of criticism from the public. FASB then agreed under pressure to encourage rather than require the use of fair value valuation.

Public pressure encouraged FASB to consider fair value valuation methods in the first place. The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the U.S. Congress urged the FASB to consider issuing standards that would use a fair value valuation method. These bodies became concerned at the lack of clear accounting for these high-payout compensation arrangements. In 1992, a bill was introduced in Congress that sought to require companies to report a compensation expense for stock options based on the fair value of the stock options. Responding to the public outcry, the FASB issued the new 1993 Exposure Draft. But because there were huge counterarguments put forth by the parties who did not want any expensing of options, the two schools of thought clearly diverged, leaving FASB with an unenviable dilemma. Supporters of the FASB Exposure Draft held to their views that these programs do have a value that needs to be recognized as a compensation expense. Supporters for fair value expensing came mostly from the academic community. The faction opposing expensing included executives (mainly from the high-tech industry), auditors, and members of Congress and of the SEC. Congress and the SEC were, in the beginning, in support of the Exposure Draft but changed their minds with the political winds and in the end opposed it.

After 2002 came a period of voluntary expensing. Many companies, on their own initiative, started using the fair value valuation methodology in their accounting for these stock options. However, public pressure continued against the excesses of executive compensation. A renewed interest surfaced for fair value expensing versus intrinsic value expensing.

The ongoing pressure on FASB to use fair value measurements grew again. Warren Buffet issued statements in favor of fair value expensing. More and more companies started using fair value expensing. (Note that the International Accounting Standards Board used fair value expensing.) However, vigorous opposition continued from the high-tech industry. High-tech companies were really concerned about the sudden erosion of their profitability position if fair value expensing were to be implemented. The inevitable happened when the FASB issued FAS 123 (finally revised in 2004). FAS 123 requires fair value valuation and associated expensing and completely does away with the intrinsic value methodology.

Note here that the valuation of stock options has nothing to do with cash flows. The only issue is expense recognition.

Finally, with the issuance of fair value expensing standards there has been a decrease in the incidence of stock option plans (because they were indeed expensive when fair value measurements were applied and these expenses are used to offset revenue).

In many cases, stock option plans have been replaced by restricted stock plans and cash-based plans.

Stock Option Expensing

Now we will analyze how stock options are expensed and accounted for based on the FAS 123 standard.

The accounting for stock options is similar to that of restricted stock. Compensation is measured at fair value and then expensed over the employment period of the employee. But the valuation of stock options requires the use of a mathematical equation.5 This mathematical equation takes into consideration the following:

5 The mathematical equation can take two forms: the Black-Scholes model and a Lattice model.

• The exercise price of the option. The exercise price is the price at which the employee can buy the option shares from the employer. Normally, the exercise price is the market price on the date the grant is made.

• Expected term of the option-exercise period.

• Current market price of the stock.

• Expected dividends.

• Expected risk-free rate of return during the term of the option.

• Expected volatility of the stock.

The mathematical model normally used for the determination of the fair value for stock options is the Black-Scholes option-pricing model. (Note that an alternative model—a lattice model, which is based on the on a binomial probability distribution—can also be used).

SFAS 123(R) called for the use of equations that would allow flexibility in modeling the ways in which employees might exercise options and also the employee-termination trends after the options vest.6 Option pricing theory is often discussed in most accounting texts. This chapter’s appendix provides you the theoretical framework.

6 “Share-Based Payment,” Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 123 (revised 2004), (Norwalk, CT: FASB 2004), par. A27–A29.

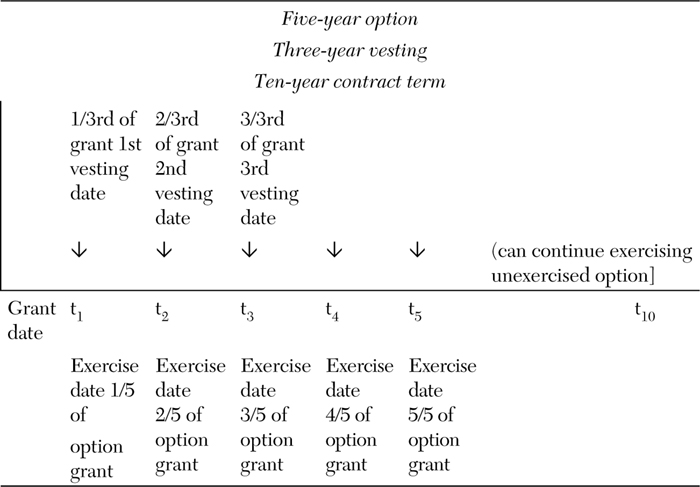

Compensation expense calculated using the option pricing equation is expensed over the duration of employment for the employee. Also, employees receiving options are not allowed to exercise their options before the expiry of specific periods of time. These time periods are called exercise periods. And even after the expiration of the exercise time period the options can still be exercised before the expiration of the contract period. Compensation expense is spread out over a vesting period—the time period over which the options are earned out. So, from the date on which the options were granted until the first date on which the plan allows an employee to earn the option is called the vesting period. Exhibit 5-4 further explains these time periods.

Exhibit 5-4. Stock Option Grant Timeline*

* Note that in this example we have purposely separated vesting and exercising sequence. In reality, these two sequences would in most cases be the same.

This timeline example is for an option granted as a five-year grant. One-fifth of the number of options granted would be eligible for exercise on the annual anniversary date of the grant. Other plan provisions would indicate that if the employee did not exercise the options granted by the end of the fifth year, the employee would get another five more years to exercise, because these options, according to the plan, have a ten-year contractual duration. At the end of ten years, the option expires and the shares are forfeited.

You need to understand the following key terms related to the accounting of stock options and FAS 123(R):

• Grant date: The date from which the employee starts benefiting from or being adversely affected by changes in the price of the stock.

• Measurement date: The date at which the fair value determination is made. If it is an equity award, the measurement date is equal to the grant date. If it is a contingent award, like a restricted stock award, the measurement date is equal to the settlement date.

• Service inception date: The date on which the service period begins.

• Tranche: The lowest common denominator of an award. Tranches separate a grant into the components in which shares or units are actually earned.

In addition, there are two basic ways by which expense amortization occurs when it comes to stock options:

• Graded amortization: The grants are broken down into tranches such that a single tranche is viewed as an independent grant. Expenses within the tranche are straight-lined.

• Straight-line: Expenses are evenly distributed across a grant based on the total vesting period and total number of shares expected to vest.

The Accounting for Stock Options

To demonstrate the process for accounting for stock options, we look at two case examples. First, we continue with the Zentec Corporation example for all Zentec’s executives. The second example introduces a different company: UMB Corporation. This case demonstrates expensing for an option where the exercise price differs from the market price on the date of the account.

Example 1

On January 1, 2013, Zentec Corporation granted options to their executives totaling 1,000,000 of the company’s $5 par value shares with a four-year vesting and exercise period. The first vesting date is January 1, 2014. The exercise price is the market price on the date of the grant, which in the continuing example is $20. The fair value of the option was calculated to be $25 (using a mathematical model).

Journal entries were as follows:

January 1, 2013 no entry

Total compensation expense:

$25 estimated fair value per option as estimated using the Black-Scholes model × 1,000,000 options granted = $25,000,000 total compensation. This is a four-year grant, so expense per year is $25,000,000 / 4 = $6,250,000 per year recorded on December 31, 2013, 2014, 2015, and 2016.

In each year, the expense that will flow to the income statement is:

The next few paragraphs cover situations that affect the accounting for stock options and therefore the compensation expense.

Forfeitures

Options are quite often forfeited before they vest. This is because of employee terminations and other reasons resulting in contract term violations. The fair value estimate needs to be adjusted for these incidents. If a forfeiture rate of 2% is expected because of historical trends, $25,000,000 would be adjusted to 98% or $24,500,000. The annual compensation would now change from $6,250,000 to $6,125,000. This forfeiture adjustment to the fair value-based compensation expense must be made on the original date of the calculation. If the forfeiture estimate needs to be changed during the four-year option term of the option, adjustments need to be made at that later date.

In the original example, on January 1, 2015, the forfeiture rate estimate, based on new evidence, is changed to 95% from 98%, and then the compensation expense for the four-year period needs to be $23,750,000 (or $5,937,500 per year). For 2013 and 2014, however, the compensation expense has been booked at $6,125,000 (or $12,250,000 for two years). However, it should have been booked at $5,937,500 per year and for two years $11,875,000. So, now only an additional $11,500,000 needs to be booked for the two remaining years, or $5,750,000 per year.

Booked for the first two years = 12,750,000

The four-year amount needs to be adjusted to = 23,750,000

So, for the next two years, the amount that needs to be booked = $23,750,000 – $12,750,000 = $11,500,000 (or $5,750,000 for each of the next two years). Of course, if estimates are changed mid-year, to be technically correct the proration of expenses should be done by the number of months in the year that the change affects.

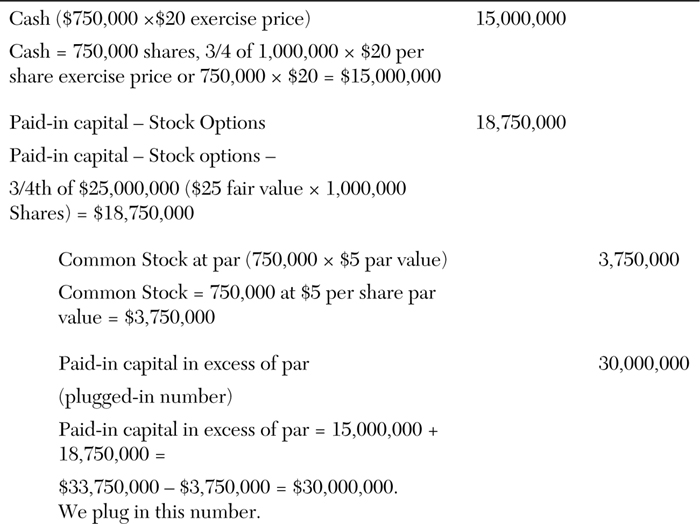

Options Exercised

Let’s assume that three quarters of these options (750,000 options) that were granted in the example were exercised by 2017 when the stock price reached $100 a share. (Wouldn’t the employees love this scenario?) But the market price given here is not relevant when it comes to the stock option valuation. Fluctuations in the market price of the stock do not affect stock option valuations.

Exhibit 5-5 shows the required journal entries.

Options Expire

Sometimes employees let the options expire without exercising them. In this example, if we assume that one quarter of the options that remained were allowed to expire, the required journal entries would be as shown here.

In this example, we have ignored the forfeitures.

Example 2

To further demonstrate the accounting entries, here is another example. To reinforce the accounting aspects of stock option expensing, we again look at the accounting entries needed for the two most common occurrences after grant: option exercise and option expiration.

The top ten managers of UMB Corporation were granted 20,000 stock options each of the company’s $5 par value common stock by the board of directors. The board granted these options effective January 1, 2013. These are options that vest over a five-year period, and the contractual term of the plan is seven years. So, the managers have seven years to exercise these options. The stipulated option exercise price is $30 per share, and the current market price for the shares is $40 per share. Therefore, these options are being granted at a discount from the market price (discounted stock options).

These options as of the date of the grant are in the money. In other words, the options have value on the grant date. These options cannot be distributed under a qualified incentive stock option plan (ISO), which has tax advantages compared to standard nonqualified stock option grants. As of January 1, 2013, they are in the money, but upon vesting they might not be in the money. It depends on the market price on the vesting dates. Also, whether the executive holds on to the stock or sells them will dictate the value that the executive will derive.

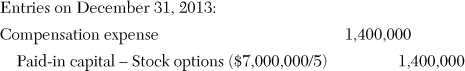

In this example, let’s also assume that the option-pricing model (Black-Scholes) UMB Corporation utilizes values these options at a fair value of $35 per share, or a total compensation expense of $7,000,000 (10 managers ×20,000 shares each ×$35 a share) or $1,400,000 per year ($7,000,000 ÷ Five-year vesting period). Note that the market price of the shares on the date of grant does not affect option expensing.

At the date of the grant, January 1, 2013, no accounting entries are made. We assume also that the service period for these managers is the same as the five-year vesting period.

UMB Corporation is allocating these expenses evenly over the five years. So at the end of each year (2013 [shown above], 2014, 2014, 2016, 2017), $1,400,000 compensation expense will be recorded. After five years, $7,000,000 will have been expensed.

Options Exercised

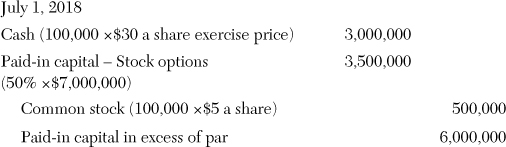

If on July 1, 2018, UMB Corporation’s managers exercise 100,000 shares of the 200,000 (10 managers × 20,000 shares each) granted (50% of the options; five and a half years after the grant date), the journal entries would be as follows:

Options Expire

If UMB Corporation’s managers do not exercise the remaining 50% of the original 200,000 shares granted and the seven-year contract term expires, the accounting entries are as follows:

Note that forfeiture rules should be applied if necessary, as demonstrated in Example 1. Forfeiture rules are applied if there were service requirements that were not fulfilled by the executive or a performance targets were not achieved.

Stock Plan with Contingencies

Some stock plans have a contingency based on a performance condition or a market condition. These conditions need to be satisfied per the plan provisions before a participating employee can benefit from the stock awarded. These conditions or contingencies can be a stipulated performance measure on any financial metric, such as, target revenue, earnings per share, sales growth, net income, operating cash, and so on. Or a condition can be established based on stock performance. The stipulation could be set indicating that the stock option or award will not be earned by the participant unless the growth in the company’s market stock price exceeds a hurdle based on a stock market index. (For example, the company’s stock price has to exceed the growth in the Dow Jones Industrial Index by over 25%.)

There are two triggers for expensing of options or awards for the company when there are contingencies set: the probability of removing the condition or the contingency, and whether the condition or contingency was indeed removed.

The compensation expense estimates take into consideration the likelihood of forfeiture, in case the contingencies and conditions are not met, and also the likelihood of exceeding the performance targets.

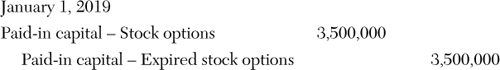

Let’s assume in the Zentec Corporation example that a performance target was established by stating the stock options or awards will be earned only if revenues grow above a 25% year-to-year growth rate. If it is determined probable that the 25% revenue growth target will be achieved, compensation expense recognition will occur, and it will be the same as in the previous example (1,000,000 shares × the fair value estimate of $25 per share, resulting in a compensation expense of $25,000,000 over the four-year term). If after two years it is determined that that 25% revenue target will not be achieved, the compensation expense estimate must be changed to zero. An accounting reversal needs to be made. The $12,500,000 amount already expensed will have to be reversed.

If the probability at the beginning of the option award four-year term is that the performance target is not going to be met, no expense needs to be recognized at the beginning of the term. Suppose, however, that in two years the probability is changed and it is determined that the performance target will be met. In that case, at that time compensation expense recognition needs to occur. However, we now know that the compensation expense estimate for the four-year period needed to be $25,000,000. So, at the end of the second year, the journal entries need to be as shown here:

Tax Implications of Stock Plans

In the United States, the tax implications of stock option expensing are governed by two regulations: FAS 123(R) and SFAS 109. These are the accounting standards dealing with treatment of stock compensation for the purposes of calculating tax expense or the income tax provision.

For tax purposes, plans can qualify as an incentive stock option (ISO), under the tax code, or the plan could be designated as a nonqualified plan. Qualified plans are called incentive stock options, and nonqualified plans are designated as nonqualified stock option plans.

For a stock option plan to be designated as a qualified plan under the tax code, the exercise price of the option needs to be the same as the market price on the date of the grant. For such plans, no taxes need to be paid until the shares are sold, and the company granting those options does not get a tax deduction for those expenses.

For nonqualified stock option plans, taxes need to be paid at the time of exercise. At the same time, the company gets a tax deduction. The deduction is calculated based on the difference between the exercise price and the market price on the date of exercise. This creates a temporary difference between accounting income and taxable income. For accounting income, the expense is deducted in the current period, but the tax deduction is taken when the options are exercised. This creates a deferred tax asset (DTA). A DTA is an expectation that at a later date a tax deduction can be taken for the share-based award that was granted. The DTA is therefore an estimated tax benefit. This applies to stock option grants and also grants under restricted stock awards. For incentive stock option grants and a 423 Plan (a stock purchase plan), there is no “temporary difference” recognized, and no DTA needs to be recorded.

Before we analyze the tax issues in detail using our continuing example of Zentec Corporation, let’s look at a simpler example that should explain the concepts being discussed. A nonqualified stock option grant of 1,000 shares is made at a fair value of $10 per share. The corporate tax rate is 40%, which results in a DTA of $4,000. Both the compensation expense ($10,000) and the DTA ($4,000) are recognized over the service period. This effectively reduces the cost of the option granted to $6,000.

Another important point to note here is that under FAS 123(R) there is a concept called the additional paid-in capital pool (the APIC pool). This account differs from the generic APIC account that is used for other specific purposes. Under FAS 123(R), when a tax deduction exceeds the compensation expense, the excess increases a temporary APIC pool. And, when the tax deduction is less than the compensation expense, the existing APIC pool is used to offset the difference. If the amount needed exceeds the remaining APIC pool, it becomes an additional tax expense.

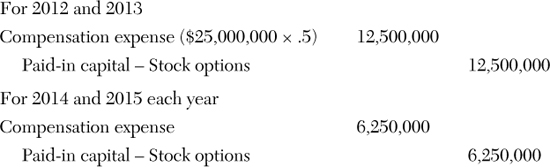

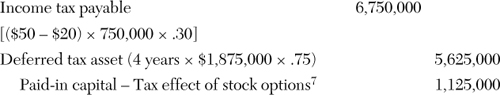

Now let’s look at the tax effects from our continuing Zentec Corporation example.

Assuming a 30% income tax rate, the following journal entries need to be made:

Assume for the Zentec Corporation example that three quarters of the options granted (1,000,000 × .75 = 750,000) at the beginning of 2013 were exercised on December 31, 2018. Assume also that the market price of the stock is $50 a share on December 31, 2018. Note the exercise price for the Zentec Corporation example is $20 a share. In this case, the tax benefit will exceed the DTA.

Note that this was a four-year grant.7

7 SFAS 109 (par. 36 c).

Now assume that the market price of the stock is $25 a share on December 31, 2019. Note the exercise price for the Zentec Corporation example is $20 a share. In this case, the tax benefit will be less than the DTA.

If the actual tax benefit is greater than the estimated tax benefit, this leads to an excess. More benefit comes to the company and this amount is posted to APIC.

If the actual tax benefit is less than the estimated tax benefit, a shortfall occurs, which provides fewer benefits to the company than originally projected. So, the company must either increase tax expense (income statement) or decrease APIC (balance sheet) to account for the shortfall. Most companies will want to decrease APIC. However, the company is permitted to decrease the APIC pool only to the extent that it exists. This creates a possible tax expense, which creates an offset against the existing APIC pool.

Here are two further examples that illustrate the concepts being discussed:

Example 1: Estimated DTA is greater than the actual tax benefit

NQ granted for 5,000 shares, price = $5

SFAS(R) expense = $4 per share × 5,000 shares = $20,000

DTA = 40% × $20,000 = $8,000

Shares exercised when market value = $10

Tax deduction = 5,000 shares × $5 gain per share = $25,000

Actual tax benefit = $25,000 × 40% = $10,000

Estimated tax benefit = $8,000

Excess = $2,000 (APIC)

Example 2: Expected DTA is less than the actual tax benefit

NQ granted for 5,000 shares, price = $3.00

Expense = $4.00 per share × 5000 shares = $20,000

DTA = 40% × $20,000 = $8,000

Shares exercised when market value = $5

Tax deduction = 5,000 shares × $2 gain per share = $10,000

Actual tax benefit = $10,000 × 40% = $4,000

Estimated tax benefit = $8,000

Shortfall = $4,000

In summary, when one is reconciling the estimated to actual tax benefit, two conditions can exist. The first exists when the estimated amount is equal to the DTA. Here we book the DTA as an expense. So, the booked amount will be the FAS 123(R) expense times the corporate tax rate. The other condition is when there is an excess or shortfall. The recognition for this condition is made at the taxable event. The actual tax benefit is calculated using the applicable corporate tax rate. The excess or shortfall is reconciled with the APIC pool. Excesses increase the APIC pool and shortfalls are offset against the existing APIC pool. If the amount needed exceeds remaining APIC pool, an additional expense is recorded.

International Tax Implications of Share-Based Employee Compensation Plans

With the growth in the globalization of business, there has been an increase in the prevalence of global employee compensation programs. Compensation programs now have to be designed for employees on worldwide basis. Therefore, we are also witnessing a growing trend in cross-border employee stock option plans. These plans must then comply with the tax laws and regulations in a wide variety of tax jurisdictions.

Stock Options

The basic tax principle affecting stock option plans is the same principle that exists for any other compensation program: The employee should be taxed when the compensation is received. In the case of options, this event occurs when the option is granted.

However, international tax policy, rules, and practice are not uniform when it comes to the policy of taxed when granted. Tax liability may arise at varying points of time, depending on the specific tax jurisdiction. The variation in practice may be guided by a particular government’s desire to tax compensation at the earliest point in time.

The taxing jurisdiction becomes a major determining factor for tax liabilities in the international arena. And the tax jurisdiction mainly depends on the country of employment. Cash compensation is normally taxed by the country in which the employee is employed. However, tax treaties often dictate that capital gain income should be taxed in the country in which the employee resides. So, conflicting practice can hinder effective decision making. An employee may be granted an equity award in one country, vest that award in another country, exercise that award in yet another country, and finally sell that award in a fourth country. Employer withholdings and even individual tax implications can differ in each jurisdiction in which the company operates and distributes shares under various employee stock-based compensation plans.

With regard to share-based employee stock plans, corporate taxpayers want to focus on the following:

• Ensure that sufficient income is earned and taxed in each tax jurisdiction so that the company can utilize all available tax credits.

• Decide whether to have maximum compliance and adhere to reporting and withholding requirements in most if not all tax jurisdictions.

• Conduct an annual review of plans for compliance with local tax laws and rules.

• Determine whether granting awards in a particular country constitutes a public offering, which might require various detailed prospectus filings.

The other international tax issues with regard to international taxation of employee share plans for U.S. multinational corporations include the following:

• U.S. multinationals must expense stock awards even if those grants are made to their non-U.S. employees working abroad.

• If the foreign operation is a branch operation of the U.S. parent, generally any income tax deduction may be taken by the parent and can also possibly be claimed as a local deduction. If the foreign operation is not a “pass-through” operation, only the local jurisdiction gets the deduction if it is allowed in that jurisdiction.

• That entity that has the most likelihood of claiming a deduction can record a DTA based on the applicable effective tax rate. And then the entity that actually claims the deduction calculates any shortfall or excess against the DTA accrued. The timing of when the ultimate tax deduction can be taken varies by local jurisdiction.

• Very few tax jurisdictions allow a tax deduction without that jurisdiction’s local entity bearing the actual cost related to the employee stock plan. So, a tax deduction strategy has to be developed. A common approach for companies is to establish intercompany chargebacks. The steps in executing global intercompany stock chargebacks are as follows:

1. The parent company delivers stock to the employee.

2. The employee pays the exercise price to the parent company.

3. The employee provides services to the foreign operation.

4. The foreign operation reimburses the parent company for the spread (the current market price minus exercise price) pursuant to a reimbursement agreement.

Other requirements might exist, too, such as documentation of a contractual obligation prior to the grant date before chargeback practices can be implemented.

IFRS Versus GAAP: Differences in Employee Stock Plan Accounting

This section examines the differences between U.S. Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) and International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) with regard to employee stock option plans. This is important because of the impending convergence between U.S. GAAP and IFRS.

In Income Tax Accounting

U.S. GAAP dictates that a DTA for a stock option should be based on the options fair value (FAS 123(R)) on the date the option is granted. A DTA is still recorded irrespective of whether the option is “out of the money.” No adjustments are made to the fair value of the underlining stock prior to the exercise or expiration date. Under IFRS, the DTA is based on the tax deduction available based on the current market price of the underlying share at each reporting date. Therefore, DTA is recognized only when the option is “in the money.” Under IFRS, in most tax jurisdictions the tax deduction is based on the intrinsic value of the stock option at exercise. This is the excess of the stock value over of the stock option exercise price. So, where exercise price equals fair value, no DTA is recognized under IFRS at the time of the grant. Tax benefits are recognized only if the fair value exceeds the exercise price. This happens as the stock price rises. Often, the tax benefit recognition trails the recorded compensation expense.

Under IFRS, because of remeasurement each reporting period caused by fair value fluctuations, the effective tax rate is subject to change. This results in volatility in the effective tax rate and the deferred accounts over the life of the stock options. This is because of the stock price changes at each recording period. And under IFRS, these changes are reported in the operating section of the statement of cash flows.

Under IFRS, the tax effect of any excess in the estimated tax deduction over the recorded compensation expense is recorded in the equity section of the balance sheet and also as a DTA. Under U.S. GAAP, only excess tax benefit recognized at the time the exercise is credited to equity in the APIC account. IFRS does not apply the U.S. GAAP concept of an APIC pool, which enables tax benefit shortfalls to be offset against aggregated prior windfalls.

The difference in the calculation of the DTA under U.S. GAAP and IFRS is demonstrated in the following example.

Let’s assume that on January 1, 2013, ABC Corporation grants 5,000 options with a grant date fair value of $20. The awards vest after five years of service. The exercise price is $33. And the share price at the end of the first year, 2013, is $35. The company’s tax rate is 30%.

The DTA under U.S. GAAP is as follows:

5,000 options × $20 × 1/5 vesting × 30% = $6,000

Under IFRS, the company calculates the DTA based on the current market share price as the reporting date of December 31, 2013:

5,000 options × ($35- $33) × 1/5 vesting × 30% = $600

Under IFRS, the tax benefit is considerably lower than under U.S. GAAP.

In Valuation and Expense Recognition

Although both IFRS and U.S. GAAP require compensation expense determination using value pricing models, the accounting for tiered options differs. IFRS requires each vesting tranche of an option to be valued using different fair values, whereas U.S. GAAP allows aggregate estimation or each tranche can be valued separately.

The amortization of the expenses under IFRS needs to be commenced on the grant date. Under U.S. GAAP, amortization can be straight-line or accelerated for awards that vest after the required service period.

For Payroll Tax Accounting

Under U.S. GAAP, a company recognizes a payroll tax liability for employee stock plans when the liability arises (that is, when the options are exercised). Under IFRS, companies can recognize an accrued payroll tax liability when the options vest. Under IFRS, Social Security taxes related to employee share plans are accrued at each reporting date. This can require payroll process changes and thus create a lot more administrative work.

Employee Share Purchase Plans

Employee share purchase plans (ESPPs) or 423 Plans generally permit employees to purchase stock at a discount or favorable terms through payroll deductions. The primary objective of these plans is to encourage employee ownership of companies. Also, these plans allow employees to purchase shares without incurring brokerage fees. Some companies, to encourage employee participation, match or partially match employee purchases.

A qualified 423 ESPP allows employees under U.S. tax law to purchase stock at a discount from fair market value without any taxes owed on the discount at the time of purchase. In some cases, a holding period is required for the purchased stock to receive favorable long-term capital gains tax treatment on a portion of your gains when the shares are sold.

A nonqualified ESPP usually is structured like qualified 423 Plan, but without the preferred tax treatment for employees.

ESPPs can be considered compensation expenses unless three conditions are satisfied:

• All employees have to be eligible to participate. No restrictions can be placed on employee participation.

• The discount provided has to be small, less than 5%. If the amount is 5% or less, no compensation needs to be recorded. Many plans have had discount percentages of 15% or more. These plans are considered compensation for tax purposes.

• The plan cannot have an option feature.

Plans that are considered compensatory should record the compensation expense over the employment service life of participating employees.

If all employees can participate and employees have no more than one month after the price is fixed to enroll and the discount is no greater than 5%, the accounting for these plans is straightforward. The company just records the sale of shares as the employee buys the shares.

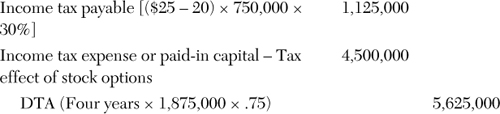

If the discount is more than 5%, the plan is considered compensation, and an expense has to be recorded. Suppose, for instance, that an employee purchases shares under the plan for $4,250 (15% discount) rather than the current market price of $5,000. The $750 discount is recorded as a compensation expense:

Stock Appreciation Rights

Stock appreciation rights (SARs) allow employees who are granted stock options to receive a cash or stock payment upon the exercise of the option. The payment of stock or cash is based on the difference between a predetermined price (usually the market price on the date of the grant) and the market price on the date of exercise. This overcomes a major disadvantage of stock option plans where the employees are required to buy the shares at the exercise price. Upon exercising his or her options, the employee has to come up with the cash. If the employee received a large grant, the cash outlay can be quite onerous. Note that the payment can be made either in cash or shares. The participant has the choice. The granting of SARs mitigates the cash-outlay disadvantage.

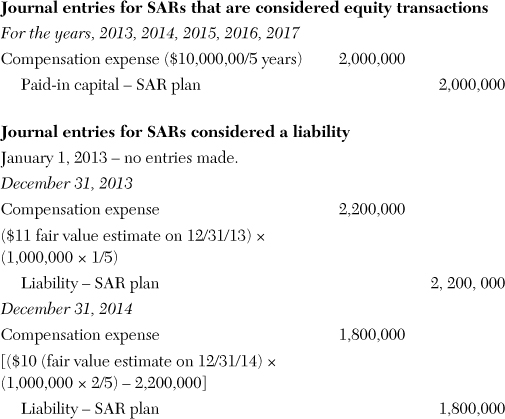

If an employer decides to settle the SAR with stock, the transaction becomes an equity transaction. If the employee elects to receive a cash settlement or has the option to elect a cash settlement, the award is then considered a liability transaction. This definition is based on the definition of liabilities under SFAS No. 6. Because a cash-settled SAR requires the transfer of an asset (cash), it is considered a liability. And if a SAR award requires the transfer of stock (equity), it is considered an equity transaction.

SARs Payable in Shares

When a SAR is considered an equity exchange (because the employer can settle the claim in stock rather than cash), the fair value of the SAR is estimated on the grant date. The compensation expense is accrued over the employment period of the employee. The fair value of the SAR is the same as that of a stock option, developed using an appropriate pricing model. The same fair value determination method is used and the compensation expense is accrued over the service life. No adjustments are made based on future changes in the stock price.

SARs Payable in Cash

For cash-settled SARs, which is a liability as stated previously, a fair value estimation is done, and a compensation expense is taken over the service period in the same way as done for options and other share-based plans. Because these plans are considered a liability, however, the fair value must be reestimated over time to continually readjust the fair value and corresponding compensation expense until it is paid.

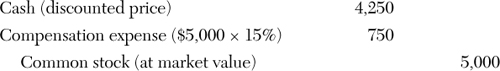

The period’s expense is that portion of the total compensation expense earned to date by SAR participants based on the fraction of the employment term that has elapsed. This amount is reduced by any already expensed amounts for past periods.

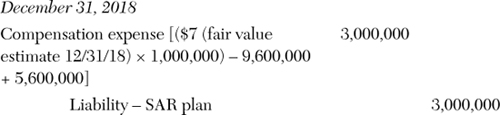

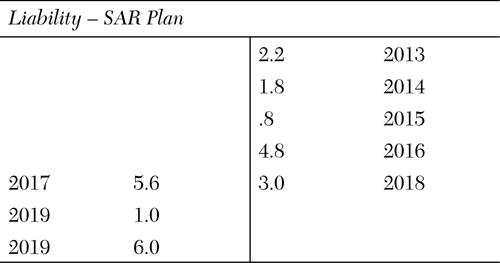

Suppose, for instance, that the fair value of the SAR at the end of a period is $10. The total compensation would be $10 million if one million SARs were to vest. Let’s assume that one million SARs were granted on January 1, 2013, and that these are five-year grants. So, the compensation expense for each year is $2,000,000 if SARs are considered to be equity. This is because the company can settle in shares at exercise. The SARs can also be considered to be a liability because there can be an election made to settle in cash. The journal entries for both these transactions are shown here.

The variability occurs in this example because of the changing market price of the stock.

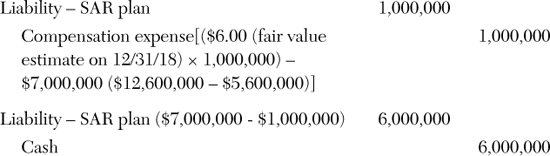

We continue to adjust both the expense and liability until the SARs are exercised or they expire. Let’s assume that in this example the SARs are exercised on September 14, 2019, when the fair value is $6.00 and the earn-out is in cash.

Exhibit 5-6 demonstrates the numbers for each year.

Exhibit 5-6. Demonstrating the Numbers with a T-account

All SARS Exercised on September 14, 2019

As you have seen in this chapter, share-based compensation has been gaining in popularity across the world. But this is an area rife with accounting, finance, and tax issues. It is a fairly technical topic. And it is imperative that compensation and benefits professional (and HR professionals) have an in-depth understanding of the accounting and finance principles behind share-based compensation. Relying exclusively on consultants is not a very good idea.

Key Concepts in This Chapter

• Restricted stock plans

• SFAS 123(R)

• Stock option expensing

• Stock plans with contingencies

• Tax implications of stock plans

• Deferred tax assets

• APIC pool

• Stock purchase plans

• Stock appreciation rights

• Incentive stock plans

• Nonqualified stock plans

• Accounting for stock options

• Option pricing theory

• International tax implications of share-based employee compensation plans

• IFRS versus U.S. GAAP with respect to share-based compensation

Appendix: Stock Options and Earnings per Share

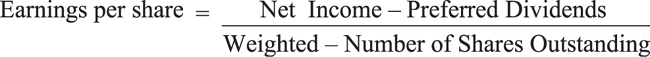

An important accounting issue with regard to employee share plans is their effect on the key accounting indicator of business success: earnings per share ratio. Stakeholders use many financial indicators to evaluate the success or failure of companies. No one indicator can be claimed to be the most important. Many believe that the earnings per share (EPS) indicator comes closest to being the most important. Because of the importance of EPS, we need to analyze how employee share-based compensation plans can affect the calculation of the EPS.

There are two ways in which the EPS indicator is presented in financial statements.

First, the basic earnings per share calculation:

To calculate the weighted average number of shares, companies must weigh the shares by the fraction of the period they are outstanding. A weighted average is used because the number of outstanding shares can fluctuate during a reporting period.

But there is second aspect to the EPS calculation. This involves complex capital structures. Companies with “complex capital structures”—those with a potential common stock impact—must also report diluted EPS.

Potentially, common stock options when exercised can increase the number of common shares, which will result in decreasing the EPS; therefore, it constitutes a complex capital structure.

Both the basic EPS and diluted EPS reflect the current earning power of a company’s common stock. But diluted EPS measures how the exercise of stock options would affect EPS in the event that all options were exercised.

Employee share-based plans like stock options are in a category of instruments that may become common stock once they are exercised. They will then dilute (reduce) earnings and are therefore called potential common shares. A company is said to have a complex capital structure if there are potential common shares involved from exercising stock options or from earning out stock awards.

For stock options, an assumption is made that the options have been exercised. Another assumption is also made that the options were exercised at the beginning of the reporting period or when the options were issued, whichever is later.

The treasury stock method is now used, which assumes that the cash proceeds from selling the new shares at the exercise price is used to buy back as many shares as possible at the stock’s average market price during the reporting year.

In the treasury stock method, an assumption is made that the options will be exercised; then, the numerator of the EPS equation increases. However, this cannot be the only assumption that is being made. If the options were exercised, that would generate cash for the company. The cash can be used in wide variety of different ways. As a matter of fact, each and every company might have a different way to use the cash, depending on their needs and desires. However, this use of cash will certainly also have an effect on the numerator (that is, net income). Under GAAP, a uniform application is applied to the EPS calculation, in the interest of intercompany comparability. So in GAAP, an assumption is made that the funds received upon exercise will be used by companies to buy back the stock of their companies at the average market price during the reporting period. Consequently, the weighted average number of shares in the denominator are increased by the difference in the number of shares exercised versus the number of shares the company buys back.

This is called the treasury stock method, based on the assumption that treasury shares are being purchased with the cash generated by the exercising of options. This treasury method, under GAAP, is an effort to create intercompany comparability.

But, two scenarios can exist when the treasury stock method is applied. If the exercise price of the option is lower than the average market price, the shares are added to the denominator (dilution occurs). If the exercise price of the option is higher than the market price of the stock, this effect reduces the number of shares in the denominator. In this case, the options are antidilutive.

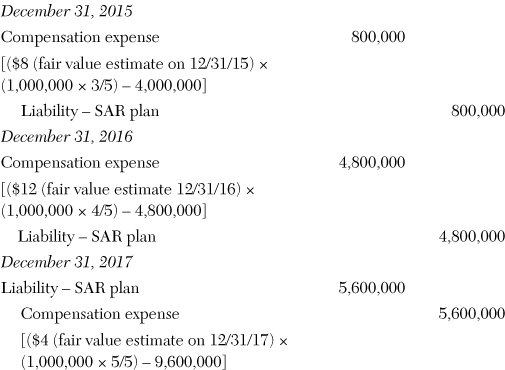

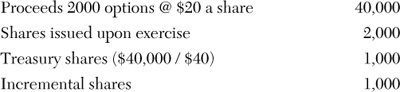

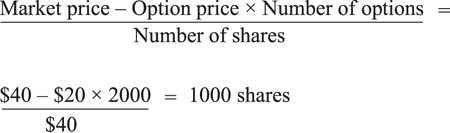

Now, let’s look at the calculations assuming that there are 2,000 options granted at an average market price of $40 per share at a point in time. The treasury method would consider that there are only 1,000 incremental shares outstanding.

Or

The impact of employee share plans on EPS depends on the plan type. For purposes of diluted EPS, accounting needs to be maintained as to when the options are being exercised so that the flow through of the effect on the numerator of the EPS equation can be updated at the EPS calculation point.

Effect of Restricted Stock

Awards of restricted stock are treated like options for EPS purposes. In most cases, unvested awards are excluded from basic EPS and are included in diluted EPS. Once vested, these awards are included in basic EPS—even if the shares haven’t actually been issued.

For purposes of computing diluted EPS, restricted stock are also considered outstanding at the beginning of a reporting period, even though they are contingent on an employee’s continued service. However, performance-based awards that are contingent on earnings or stock price targets are not included in diluted EPS unless those targets are being met as of the end of the reporting period.