9. Healthcare Benefits Cost Management

Aims and objectives of this chapter

• Discuss healthcare benefits cost containment

• Expose the causes for the escalating costs of healthcare benefit programs

• Consider various healthcare cost management options.

• Review consumer-driven healthcare cost containment initiatives

• Examine health savings accounts

• Discuss health reimbursement accounts

• Examine flexible spending accounts

• Discuss utilization reviews

• Discuss corporate wellness programs

• Model the forecasting of healthcare benefit program costs

This chapter examines healthcare benefits costs for employers only. Because this category of employee benefits is the major component of the total employee benefits program, understanding and forecasting these costs accurately is vital. After all, on average, the cost of a total employee benefit program is about 30% of the total compensation program costs in most organizations. So, in most organizations, this is a big-ticket cost, requiring close analysis and monitoring.

The Background

Any book about financial and accounting aspects of human resource (HR) management must examine the escalating costs of employer-sponsored healthcare programs. The cost of this one element of the total compensation system has been continually rising, and so organizations need to exert sufficient analytical rigor and, when possible, implement fairly stringent cost-containment measures. Rising overall costs of doing business and stiff global competition make this even more of a business imperative.

Medical costs, which seem to continually increase, are a hot-button issue. Recent media coverage of the subject has been extensive, fueling emotions and ongoing political debates. With the Affordable Care Act (ObamaCare) signed into law, and the Supreme Court upholding its constitutionality, the issue remains at the forefront of our current societal dialogue and so must also be addressed by decision makers in business organizations.

The overall inflation rate (of all goods and services) has been around 2.3% since the year 2002. In contrast, the average annual premium for family healthcare coverage through an employer-sponsored plan reached $15,073 in 2011, an increase of 9% over the previous year (according to a Kaiser Family Foundation study). The annual growth in premiums has slowed in recent years to 5%, however, rising just 3% in 2010. Double-digit increases in medical premiums were the norm for a long time, so any relief from that is most welcome. Note, however, that overall the cost of family coverage has doubled since 2001, when premiums averaged $7,061, compared with a 34% gain in wages over the same period, according to the New York Times.1 Any moderation in the inflation rate of medical premiums for employers is the result of the slowing down of the economy since 2008 (and the not-so-robust economic recovery since then). Nevertheless, the same NY Times article suggests that employers expect to see medical premiums increasing at an annual rate of about 5% over the next few years.

1 Data from www.nytimes.com/2011/09/28/business/health-insurance-costs-rise-sharply-this-year-study-shows.

Note, as well, that since the recession of 2008-2009 and the weak recovery thereafter the number of people covered by employer-sponsored healthcare programs has steadily declined. In a comprehensive briefing paper published by the Economic Policy Institute, author Elise Gould provides some interesting statistics derived from an analysis from U.S. Census Bureau data.2 She states that for the entire under-65 population, the number of those covered by employer-sponsored medical benefit coverage fell from about 170 million to about 157 million from 2000/2001 to 2009/2010. This indicates that more and more people are uninsured because they are not in an employer-sponsored plan.

2 Gould, Elise, “A Decade of Declines in Employer-Sponsored Health Insurance Coverage,” EPI Briefing Paper #337, February 23, 2012.

The contributing factor is that over the past four years unemployment has been in the range of 8% to 10%. This is a good and a bad piece of information. Because the number of covered employees has been going down, the total cost of medical coverage has been (most probably) decreasing along with it. However, many people are currently unemployed. During their unemployment period, they could be on COBRA (Consolidated Omnibus Budget Recovery Act) coverage for up to 18 months. When their COBRA expires, they often go uninsured. When they need medical care, the uninsured go to the public hospitals and receive care free of charge. However, somebody has to pick up the tab for the uninsured. And most likely, the remaining working employees pick up this tab with higher premiums and with rising doctor fees and hospital costs.

In 2010, 49.1 million people under 65 were uninsured. This is a huge indirect cost, borne by those covered by employer-sponsored medical plans. Therefore, rising medical premiums and unit coverage costs offset any potential savings from fewer persons being covered. So, even as the number of people covered by employer-sponsored medical plans declines, the cost of medical plans continues to climb faster than the overall inflation rate. For example, since 2001, premiums for employer-sponsored health coverage for families have increased by 113%, placing more cost burdens on employers and workers. And health expenditures in the United States neared $2.6 trillion in 2010, more than ten times the $256 billion spent in 1980.3 According to the Congressional Budget Office, between 1975 and 2005, annual per-person health spending in the United States rose, on average, 2% faster than per-person economic growth.

3 U.S. Healthcare Costs, Kaiser EDU.org, Health policy explained, www.kaiseredu.org/issue-modules/us-health-care-costs/background-brief.aspx.

The Reasons for the Rising Costs

Many factors have contributed to the ever-rising cost of employer-sponsored medical benefit programs (medical premiums), including the following:

• Cost of medical malpractice insurance

• The unusually high increase in hospital costs

• The ever-increasing number of underinsured and uninsured who need care (which adds indirectly to the cost of medical premiums because the payers [hospitals, doctors, and insurance companies] are forced to pass these costs on to regular plan participants)

• The increasing demand for medical services from an expanding population base

• The consumer demand for better medical care and services

This is a plethora of reasons—many factors contributing to increasing costs. Many of these reasons are situational and not necessarily caused by problems within the structures of medical care.

There are other reasons for the rising costs as well. Among these is that for several years spending on prescription drugs has been a primary contributor to the increase in overall healthcare spending. Analysts state that the availability of more expensive prescription drugs, with their high development costs, is contributing to the rising costs.

Similarly, state-of-the-art medical technologies fuel healthcare spending through development costs and the subsequent demand for more costly services. These technologies might be improving quality of diagnosis and care, but they might not necessarily be cost-effective.

People in general are living longer, but they often face severe diseases as they do so. This places a tremendous demand on the healthcare system. Severe chronic diseases account for more than 70% of total healthcare expenses. Treatment of heart disease, obesity, diabetes, and other long-term disease conditions contributes to the rise in healthcare costs. In addition, as the population ages, use of medical care increases, with the cost of care rising with a person’s age. Data indicates that in the last two years of a person’s life is when the highest healthcare expenses are incurred.

Another reason for the rising costs is the inefficiency and the waste in the system. There is evidence that an excess of 25% of healthcare spending (or more $600 billion) a year can be traced to inefficiency and waste.4

4 Chanin, Jeffrey, Parke, Robert, and Mirkin, David, “Insight – Expert Thinking from Milliman,” Want to manage employer healthcare costs? It starts with managing utilization, March 18, 2010, http://insight.milliman.com/article.php?cntid=7217.

Businesses are always scrambling to improve their bottom lines. And because of the increasing pressures from rising costs of medical plans and because of pending regulations (for example, the Affordable Care Act), businesses remain vigilant about this major cost element that can affect their bottom lines directly. All of this evidence suggests that management will continue to challenge the HR and benefits department staff to build various cost-containment measures in to their healthcare plan designs, annual updates, and revisions.

Nevertheless, this is a joint responsibility of the HR staff and the accounting staff. One activity where cooperation is essential is in projecting as accurately as possible the future costs of medical benefit programs. Accurate costs are essential for effective financial planning, budgeting, and overall effective managerial accounting. We discuss the projecting of medical benefit costs later on in this chapter.

Much has been written and published on the subject of healthcare costs and their containment, with entire books and numerous articles devoted to the subject. Even so, the objective of this chapter is to review the issue of healthcare costs from the employer’s point of view and to discuss various cost-containment alternatives that can be built in to medical benefit plan designs.

The main objective for the employer in providing employees with a medical plan benefit is to help employees mitigate the financial risks associated with getting sick, both on minor and major illnesses. The mitigation of the risks is done for both the employee and his or her direct family. Major exposure arises when the employee or any member of his or her family becomes severely ill for whatever reason. These can be catastrophic events. Another primary reason that employers provide medical benefits to employees is to ensure that the employee stays physically healthy so that the employee currently is and continues to be productive for the entire duration of the employee’s service life within the organization.

So, the medical benefit plan is an important component of the total compensation program. But costs need to be managed by building various cost-containment features into the design of the plan and by systematically forecasting these costs for effective managerial budgeting and control. We now look first at cost-containment ideas and concepts. Then the discussion turns to the issue of forecasting and budgeting medical benefit expenses.

Cost Containment Alternatives

Healthcare benefit is one of the keys to the hiring and retaining of critical employees. So, when this benefit costs the employer large sums of money, it becomes imperative that these costs be analyzed and containment measures be put into place. Many cost-containment ideas and concepts have been floated. This discussion focuses on the most direct and concrete concepts for the cost containment of healthcare expenses.

Consumer-Driven Healthcare

One concrete way to contain costs has been given the broad designation of consumer-driven healthcare. The fundamental principle here is that individuals are in control of their health condition—the good and the bad. The individual can direct the medical care expenditure by choosing a healthy lifestyle, by controlling diet, and by exercising. Consumer-driven healthcare advocates that the individual should self-direct these expenditures with monies they directly set aside as a saving for the eventuality of these expenses (with some structural facilitation provided by employers and the government). After all, when the employees are spending their own money, it makes them responsible purchasers of healthcare and they create the necessary cost-containment measures by themselves for themselves.

Self-directed healthcare programs that have been introduced in the recent past include

• Health savings accounts

• Health reimbursement accounts

• Flexible spending accounts (not really a consumer-driven cost-containment initiative, but rather a pretax spending provision)

Health Savings Accounts

Health savings accounts (HSAs) were created in 2003 so that individuals covered by high-deductible health plans could receive tax-preferred treatment of money saved for medical expenses. Generally, an adult who is covered by a high-deductible health plan (and has no other first-dollar coverage) may establish an HSA.

The caveat for the establishment of an HSA is that an individual is eligible for an HSA only if he or she is covered by a high-deductible health plan. A high-deductible health plan (HDHP) is a health insurance plan with lower premiums and higher deductibles than a traditional health plan. HDHPs are usually for catastrophic coverage, intended to cover specific catastrophic illnesses.

HSAs were established as part of the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act, which was signed into law by President George W. Bush on December 8, 2003.

A survey conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation in September 2008 found that 8% of covered workers were enrolled in a consumer-driven health plan (including both HSAs and health reimbursement accounts), up from 4% in 2006. The study found that roughly 10% of firms offered such plans to their workers. Evidence suggests that the vast majority of HSA plans were employer-sponsored plans and about 25% of the total plans were individually set up. Another survey, done by America’s Health Insurance Plans (AHIP), provides confirming evidence. They reported that the number of Americans covered by HSA-qualified plans had grown to 6.1 million as of January 2008 (4.6 million through employer-sponsored plans and 1.5 million covered by individually purchased HSA-qualified plans).

Evidence gleaned from various data sources on the use of HSAs since inception finds that contributions to these plans far outstrip the withdrawals. Contributions are normally almost double the withdrawals.

Contributions to an HSA may be made by any individual member of an HSA-eligible high-deductible health plan or by their employer, or by any other person. If the employer makes a contribution to such a plan, the plan is considered the same as any other Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) qualified plan, and nondiscrimination rules become effective. If contributions are made through a Section 125 plan, however, nondiscrimination rules do not apply.

Employers have flexibility in the design of the plans in that they may treat full-time and part-time employees differently. Employers may also treat individual and family participants differently.

Contributions from an employer or employee may be made on a pretax basis through an employer. In the absence of employer contributions, contributions may be made on a post-tax basis and then used to decrease gross taxable income the following year.

The main advantage of making pretax contributions is the ability to avoid the FICA and the Medicare tax deduction, which amounts to a savings of 7.65%. Because of the temporary Social Security tax rate holiday, the 7.65% number may be different for employees. The stated percentage applies to employer and employee (subject to limits of the Social Security Wage Base). Regardless of the method or tax savings associated with the deposit, the deposits may only be made for persons covered under an HSA-eligible high-deductible plan.

Initially, the annual maximum deposit to an HSA was the lesser of the actual deductible or specified Internal Revenue Service (IRS) limits. Congress later abolished the limit based on the deductible and set statutory limits for maximum contributions. All contributions to an HSA, regardless of source, count toward the annual maximum. A catch-up provision also applies for plan participants who are age 55 or older, allowing the IRS limit to be increased.

All deposits to an HSA become the property of the policyholder, regardless of the source of the deposit. Funds deposited but not withdrawn each year carry over into the next year. Policyholders who end their HSA-eligible insurance coverage lose eligibility to deposit further funds, but funds already in the HSA remain available for use.

The Tax Relief and Health Care Act of 2006, signed into law on December 20, 2006, added a provision allowing a one-time rollover of Individual Retirement Account (IRA) assets to be used to fund up to one year’s maximum HSA contribution. State tax treatment of HSAs varies. According to IRS Publication 969: Health Savings Accounts and Other Tax-Favored Health Plans, an individual can generally make contributions to an HSA for a given tax year until the deadline for filing income tax returns for that year, which is typically April 15.

IRS-stipulated contributions for the years 2012 and 2013 are as follows, respectively:

• Single: $3,100 and $3,250

• Family: $6,250 and $6,450

Funds in an HSA can be invested in investments similar to the investments made in IRA funds. Investment earnings are sheltered from taxation until the money is withdrawn.

HSAs funds can be “rolled over” from fund to fund. However, an HSA cannot be rolled into an IRA or a 401(k), and funds from IRAs and similar investments cannot be rolled into an HSA, except for the one-time IRA transfer mentioned earlier.

Unlike some employer contributions to a 401(k) plan, all HSA contributions belong to the participant immediately, regardless of the deposit source. HSA participants do not have to obtain advance approval from their HSA trustee or their medical insurer to withdraw funds, and the funds are not subject to income tax if made for qualified medical expenses. These include costs for services and items covered by the health plan but subject to cost sharing, such as a deductible and coinsurance or copayments. Funds can be withdrawn for expenses not covered under medical plans (such as dental, vision, and chiropractic care; durable medical equipment such as eyeglasses and hearing aids; and transportation expenses related to medical care). Through December 31, 2010, nonprescription over-the-counter medications were also eligible. Beginning January 1, 2011, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, also known as Health Care Reform, stipulates HSA funds can no longer be used to buy over-the-counter drugs without a doctor’s prescription.

There are several ways that funds in an HSA can be withdrawn, such as through a debit card, personal checks, and a reimbursement process similar to medical insurance. Funds can be withdrawn for any reason, but withdrawals that are not for documented qualified medical expenses are subject to income taxes and a 20% penalty. The 20% tax penalty is waived for persons who have reached the age of 65 or have become disabled at the time of the withdrawal. Then, only income tax is paid on the withdrawal, and in effect the account has grown tax deferred (similar to an IRA). Medical expenses continue to be tax free. Prior to January 1, 2011, when new rules governing HSAs in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act went in to effect, the penalty for nonqualified withdrawals was 10%.

Account holders are required to retain documentation for their qualified medical expenses. Failure to retain and provide documentation could cause the IRS to rule withdrawals were not for qualified medical expenses and subject the taxpayer to additional penalties.

The HSA plan is an innovation whose primary objective was to contain healthcare costs for employers. It is believed that HSAs should reduce the growth of healthcare costs and increase the efficiency of the healthcare system. When individuals spend their own money, it makes them responsible purchasers of healthcare. They pursue cost-effective choices. Many believe that individuals who see that they are having to pay the medical expenses themselves will consume less medical care, ask the doctors more questions about tests and medical exams, shop for lower-cost options, and be more vigilant against excess and fraud in the healthcare industry. For all these reasons, the HSA program has great value as a cost-containment measure.

Two other plans fall within the genre of consumer-driven health plans. These plans have similar objectives but differ in structure.

Health Reimbursement Arrangement

Health reimbursement accounts or health reimbursement arrangements (HRAs) are IRS-approved programs that allow an employer to set aside funds to reimburse medical expenses that have been paid by employees. HRA programs have tax advantages for both employees and employers.

An HRA is an account offered to employees or retirees that the employee can use to pay for deductible and co-insurance amounts or covered medical expenses. Like an HSA, leftover dollars generally can be used from year to year, as long as the employee continues to be a member of the plan. Also, the money is contributed by the employer and doesn’t count as income, saving valuable tax dollars.

Employers set up HRA programs and then engage a third-party administrator to manage the program. A feature of this plan can be that participants would be allowed to roll over plan balances from one year to the next. However, the employer needs to decide how much can be rolled over from one year to the next. This can be stipulated as a percentage or a flat amount.

According to the IRS, an HRA “must be funded solely by an employer,” and contributions cannot be paid through a voluntary salary-reduction agreement. No limit applies to the employer’s contributions, which are excluded from an employee’s income.

Per the IRS regulations documented in IRS Publication 96, “Employees are reimbursed tax free for qualified medical expenses up to a maximum dollar amount for a coverage period.” HRAs reimburse only those items (copays, coinsurance, deductibles, and services) agreed to by the employer that are not covered by the company’s standard insurance plan. With an HRA, employers fund individual reimbursement accounts for their employees and define what those funds can be used for.

Before a plan is implemented, qualified claims must be described in the HRA plan document. Approved reimbursements could be for medical services, dental services, copays, coinsurance, and deductibles. But these reimbursement guidelines can vary from plan to plan. The employer is not required to prepay into a fund for reimbursements. Instead, the employer can reimburse employee claims as they occur.

Reimbursements under an HRA can be made for current and former employees, spouses, and any person the employee could have claimed as a dependent on the employee’s tax return (with stipulated exceptions).

The biggest cost-containment advantage of an HRA plan is that employers will have predictability regarding their expenses in providing attractive healthcare benefits for their employees. Employers will know their maximum expense liabilities.

Flexible Spending Accounts

As indicated earlier, flexible spending accounts (FSAs) cannot be classified as a cost-containment device for the employer. Instead, an FSA is more of a program that facilitates employees spending their own money on healthcare and dependent care expenses. In such programs, an individual can set aside a certain percentage of earnings to pay for qualified expenses, mostly medical expenses and dependent care expenses. The money set aside by the individual is not subject to payroll taxes. A major disadvantage of an FSA is that funds not used in an FSA by the end of the year are lost to the employee. This is not the case with an HSA.

The most common type of FSA is a medical-expense FSA. HSAs and FSAs are similar in nature. The main difference is that an HSA is offered as a component of a consumer-driven healthcare plan, whereas an FSA can also be offered with a traditional health benefit plan.

An FSA plan can have two components; one is for qualified medical expenses, and the other is for dependent care expenses.

Medical-Expense FSA

The most common type of FSA is used to pay for medical expenses not paid for by insurance, usually deductibles, copayments, and coinsurance amounts. As of January 1, 2011, over-the-counter medications are allowed only when purchased with a doctor’s prescription, with the exception of insulin. Over-the-counter medical devices, such as bandages, crutches, and eyeglass repair kits, are covered.

Prior to the enactment of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, the IRS permitted employers to set any maximum annual amount for their employees. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act amended Section 125 such that FSAs cannot allow employees to choose an annual election in excess of a limit determined by the IRS. The annual limit will be $2,500 for the first plan year beginning after December 31, 2012. The IRS will index subsequent plan years’ limits for cost-of-living adjustments. Employers have the option to limit their employees’ annual elections further. This change starts in plan years that begin after December 31, 2012. The limit is applied to each employee, without regard to whether the employee has a spouse or children. Nonelective contributions made by the employer that are not deducted from the employee’s wages are not counted against the limit. An employee employed by multiple unrelated employers may elect an amount up to the limit under each employer’s plan. The limit does not apply to HSAs, HRAs, or the employee’s share of the cost of employer-sponsored health insurance coverage.5

5 All the provisions stated have been derived from http://healthcare.gov and from the IRS Web site http://irs.gov.

Dependent Care FSA

FSAs can also be established to pay for certain expenses to care for dependents who live with someone while that person is at work. The dependent care FSA is federally capped at $5,000 per year, per household. Married spouses can each elect an FSA, but their total combined elections cannot exceed $5,000. At tax time, all withdrawals in excess of $5,000 are taxed.

Other FSA Provisions

An FSA’s coverage period ends either at the time the plan year ends or at the time when coverage under the plan ends.

In recent years, the FSA debit card was developed to allow employees to access the FSA directly. It also simplified the substantiation requirement, which required labor-intensive claims processing.

A drawback to the FSA program is that the money set aside must be spent “within the coverage period” as defined by the benefits plan coverage definition. The plan year is commonly defined as the calendar year. Monies left unspent at the end of the coverage period are forfeited. These funds can be used for administrative costs or can be equally distributed as taxable income among all plan participants. The coverage period ceases with the termination of employment, whether the employee or the employer initiated the termination. The exception to the rule is when the employee continues coverage with the company under COBRA or another arrangement.

The next most direct and concrete way to contain healthcare expenses are utilization reviews.

Utilization Reviews

The utilization review process has been used for awhile now. It is a process that determines whether medical services are appropriate and necessary. The process helps the organization minimize costs. Utilization reviews take various forms, including the following:

• Preadmission review for scheduled hospitalization (precertification review)

• Admission review for unscheduled hospitalization (precertification review)

• Second opinions for elective surgeries (precertification reviews)

• Concurrent reviews

• Individual case retrospective reviews

• Aggregate plan retrospective reviews

Insurance companies engage doctors and other healthcare professionals to perform these reviews. The reviews could also be conducted by independent agencies. In utilization reviews, there is a need to balance the desire to directly reduce the volume of services provided and the desire to increase the quality of care.

There are various types of utilization reviews. First is the precertification review. This is the preapproval process for treatments that the insurance companies have designated require precertification before the medical care is provided. Most precertification lists include nonemergency hospitalizations, outpatient surgery, skilled nursing and rehabilitation services, home care services, and some home medical equipment. The review and approval involves determining whether the requested service is medically necessary.

Most insurance plans have predetermined criteria or clinical guidelines of care for a given condition. Once the precertification request is submitted to the insurance company, a committee reviews these guidelines and determines whether the particular case meets the criteria for precertification coverage. If necessary, the committee may contact the healthcare provider. The process begins with data collection, including the symptoms, diagnosis, results of any lab tests, and a list of required services. The committee then reviews the submitted case against the criteria for the given condition. It may compare the medical information provided to the health plan’s medical-necessity benchmarks.

The second type of a review is the concurrent review. Concurrent reviews are used for approval of medically necessary treatments or services. Concurrent reviews are conducted during active management of a condition. This could be inpatient or ongoing outpatient care. The main objective of a concurrent review is to make sure that the patient is getting the right care in a timely and cost-effective way. After the physician has started a specific course of medical treatment, any new treatments found on the insurance companies’ preapproval list are submitted to the insurance company for approval. Information is collected on the care provided up to that point in time. Information on clinical status and any progress or lack thereof is collected. Once the insurance company or an independent review organization reviews the information, the physician and other providers are informed as to the insurance company’s position with respect to the particular case.

An important part of concurrent review is the assessment of the need for continued hospitalization. This is because a primary objective of the concurrent review is to decrease the amount of time the patient remains in the hospital. Often, the concurrent review feedback includes a specific discharge plan. This plan can include transfers to rehabilitation, hospice, or nursing facilities. Although discharge plans often change due to complications or abnormal test results, it is very important to minimize length of hospital stays to contain costs.

The final type of utilization review is the retrospective review. In this review, medical records are audited on the particular case after the treatment is completed. The retrospective review takes two forms. One reviews a particular plan’s aggregate utilization statistics, and the other deals with individual cases.

The insurance company can use the results to approve or deny coverage an individual has already received. The particulars of individual cases are compared to those of other patients with the same condition. Based on the retrospective review of the individual cases, the insurance company may revise treatment guidelines and criteria for that specific condition.

The other function of an individual case retrospective review is the after-the-fact approval of treatments that were conducted without precertification approvals. This can happen if a particular case was an extreme medical emergency and so time prevented the parties involved from securing precertification approvals. Emergency acute care surgeries often result in requesting eligibility for this type of review. The review takes place before any payment is made to the provider or hospital.

The second type of retrospective utilization reviews is the aggregate group review done by the insurance company for the plan sponsor. The plan sponsor, because of confidentiality laws, cannot be shown review results for individual cases. So, they need statistical data in aggregates. Here, average statistics on incident experience is provided for that particular plan sponsor compared to appropriate benchmarks. The health insurance company, an independent review organization, or the hospital involved in the treatment can conduct retrospective reviews.

The term utilization management is often used interchangeably with the term utilization review. Because the plan sponsor has to foot the bill for all medical costs in an employer-sponsored healthcare plan, they demonstrate the most concern as to how these expenses are being managed. Now, because of advances in information technology, plan sponsors require intermediaries (brokers and insurance companies) to provide them with empirical data about plan utilization. They are also requesting that this data be analyzed to provide them appropriate benchmark studies. Employers believe these studies can help them with their cost-containment efforts by showing them areas for utilization improvement, better waste management potential, and improved ways to adhere to evidence-based medical practices.

Corporate Wellness Programs

Another much discussed healthcare cost containment concept is to encourage and motivate employees to stay healthy. These programs usually fall under the generic title corporate wellness programs.

Proponents of this concept contend that there are many hidden costs of poor health. In a U.S. Chamber of Commerce innovative publication, Leading by Example,6 Dan Ustian, president and CEO of Lincoln Plating, suggests that the main hidden costs of an unhealthy employee population base are (1) higher direct healthcare costs, (2) lower worker output, (3) higher rates of disability, (4) higher rates of absenteeism, (5) higher rates of injury, and (6) more workers’ compensation claims. So, according to Mr. Ustian, it is important to understand the factors that are connecting the health of the organization’s employees and the corporate performance.

6 Leading by Example, Leading Practices for Employee Health Management, U.S. Chamber of Commerce and the Partnership for Prevention, 2007.

In the U.S. Chamber of Commerce study, a new concept was introduced with regard to corporate health: presenteeism. It suggests that there are instances of diminished worker productivity on the job attributable to employee poor health conditions. This leads to an increased concern that unmanaged health conditions such as diabetes, migraine headaches, or asthma attacks can affect on-the-job productivity of workers. Thus, negative employee health factors are of concern to many companies.

The saying “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure” suggests that preventive services under the title wellness programs should be implemented as a cost-containment measure. As mentioned in the U.S. Chamber of Commerce study, Intel’s president and CEO, Paul Otellini,7 talks about a landmark study done by the Partnership for Prevention. In the study, they assessed the impact of 25 preventive health services recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force and the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.8 Preventive services recommended included

7 Ibid.

8 Maciosek, M.V., Coffield, A.B., Edwards, N.M., Goodman, M.J., Flottemesch, T.J., and Solberg, L.I., “Priorities among effective clinical preventive services: Results of a systematic review and analysis,” American Journal Preventive Medicine, Vol. 31, No. 1, 2006, pp. 52–56, http://www.prevent.org/data/files/initiatives/prioritiesamongeffectiveclinicalpreventivesvcsresultsofreviewandanalysis.pdf

• Tobacco-use screening/brief intervention

• Colorectal cancer screening

• Hypertension screening

• Influenza immunization

• Problem drinking screening/brief counseling

• Cervical cancer screening

• Cholesterol screening

The report suggests that companies that are instituting healthcare cost-containment measures should examine their current healthcare benefit programs and determine whether coverage gaps exist with respect to preventive services. If the gaps do exist, they should fill the gaps with the addition of the highest-priority preventive services. They should also consider providing incentives for preventive healthcare by reducing out-of-pocket costs for preventive services. They should also educate employees proactively on the value of preventive services and the resources provided under the company-sponsored healthcare plan.

It has also been suggested that companies need to add a health-promotion program as part of their healthcare cost-containment efforts. “The main goals of health promotion are to reduce health risks and optimize health and productivity while lowering total health-related costs,” says Andrew N. Liveris, chairman and CEO of Erickson Retirement Communities in the same U.S. Chamber of Commerce and Partnership for Prevention report.9 A health-promotion program includes

9 Ibid.

• Supportive environments

• Integration with the company’s ongoing programs and structures

• Health screening

In an effort to promote wellness, companies provide employees with health coaches and risk assessments. Individuals who meet wellness goals are rewarded with discounts off annual premiums. Firms also sponsor wellness committees whose job is to create awareness and to develop promotional and competitive activities. The idea is to engage employees by encouraging each other to stay healthy in an effort to contain the costs as well as increase employee engagement and at the same time increase productivity.

Finally, proponents of organizational wellness programs suggest that return on investment on dollars spent for wellness programs can be much above 100%. It is better to pay for preventive medicine than to spend large sums of money on catastrophic illnesses. That argument is hard to refute.

Other Cost Containment Alternatives

In addition to the core concepts that have been reviewed so far, other healthcare cost-containment measures include the following:

• Discount drug programs: Many large retailers (for instance, Wal-Mart) have deep-discount prescription drug programs. Companies should offer the programs to employees and then encourage employees to use the programs. A significant employee participation in such programs can assist organizations with their healthcare costs-containment programs.

• Spousal coverage: An employee’s spouse can often secure coverage at his or her own place of employment. In these cases, organizations have a provision in their plans stating that if an employee’s spouse has comparable coverage available at their place of employment the employee’s employer will not cover the spouse. Some companies impose a surcharge in these situations.

• Self-funding: With the costs rising and with uncertainties of the new healthcare reform, organizations are considering self-funding as a real cost-containment alternative.

Forecasting Healthcare Benefit Costs

The final topic this chapter covers is forecasting the cost of healthcare benefit programs for budgeting purposes. After all, if we want to contain costs for this ever-increasing component of the total compensation system, we need to develop accurate forecasts and budgets so that the actual expenses can be compared to the forecasts and budgets and then managed with clarity.

A macro goal for most organizations is that the overall benefit program (including costs of the healthcare benefits) should account for approximately 30% of total compensation costs. This will provide an overall total benefits cost target.

Historical data collection on the breakdown of each benefit line item should be undertaken. Here is a comprehensive list of all the benefit components:

• Legally required benefits mandated by various laws

• Medical benefits

• Disability benefits (mandatory and supplementary)

• Group life insurance (company provided and supplementary)

• Accidental death and dismemberment insurance

• Defined benefit pension plan (if the organization has one)

• Defined contribution pension plan (404(k))

• Vision and dental care plans

• Employee service plans

• Employee advisory services

Here is a step-by-step process to develop a fairly accurate forecast for the healthcare benefit program for an upcoming budget year:

1. Collect data on the historical expenditures for each of the line items listed here. Collect data on as many years as possible (from a data-retrievable-ease point of view).

2. After collecting the data, calculate an average dollar cost across the years.

3. An average dollar cost weighted by the total employee population is desirable.

4. Calculate a total dollar cost for all benefit line items.

5. Calculate a percentage for each line item cost of the total weighted average cost.

6. Determine the 30% total benefits cost target with the assistance of the accounting department for the budget year. This measure is usually called–the benefit burden rate.

7. After deriving the 30% total dollar number, apply the percentage numbers calculated in a previous step to the forecasted 30% budgeted total benefits number to determine the budgeted dollar number for each line item benefit budgeted cost.

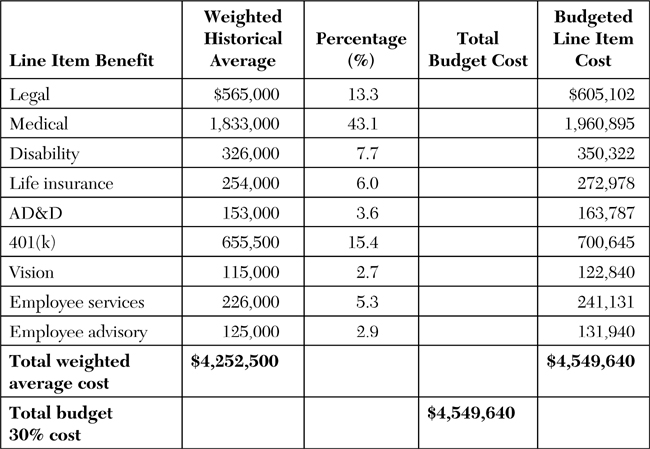

Using this method, organizations can determine the total budgeted cost for the healthcare benefit plan for the upcoming year, as shown in Exhibit 9-1.

Exhibit 9-1. Benefit Cost Forecasting

The budgeted healthcare benefits for the upcoming year in this example are $1,960,895. As shown in this exhibit, healthcare benefit costs are the largest line item benefit cost in most organizations. This budgeted healthcare cost number should be used to develop the specifics of the healthcare program next year.

As a final point about healthcare cost containment, most organizations should shop around every year for a better deal for their healthcare dollar. Those who shop may find opportunities to change carriers for better rates. Just because an employer receives a small rate increase from their existing carrier does not mean that all other carriers will charge the same rates. Of course, you must watch out for loss-leading practices. Remember, insurance companies pay benefit brokers, and their motivations are not directed toward earning a lower commission for the benefit of their clients. Instead, they seek to maximize their commission earnings. So, buyer beware!

Key Concepts in This Chapter

• Consumer-driven healthcare

• Health savings accounts

• Health reimbursement accounts

• Flexible spending accounts

• Utilization reviews

• Utilization management

• Healthcare cost-containment challenges

• Corporate wellness programs

• Forecasting healthcare benefit programs

• Precertification reviews

• Concurrent reviews

• Retrospective reviews