10. The Accounting and Financing of Retirement Plans

Aims and objectives of this chapter

• Establish a framework for employer-sponsored pension plans

• Further explain the difference between defined-benefit and defined-contribution pension plans

• Discuss the accounting for pension plans

• Review the accounting of defined contribution pension plans

• Explain accounting issues surrounding loans under defined contribution pension plans

• Discuss the accounting of defined benefit pension plans

• Explain the concept of income-replacement ratio

• Explain the reasons for the decrease in the use of defined benefit pension plans

• Explain the role of the actuary in the determination of defined benefit plan costs

• Discuss all the components involved in the accounting of defined-benefit pension plans

• Explain all elements of the pension benefit obligation

• Explain the accumulated benefit obligation

• Explain the vested benefit obligation

• Explain the projected benefit obligation

• Discuss the role of Pension Benefit Guarantee Corporation

• Examine the elements involved in accounting for the PBO changes

• Discuss the elements involved in the accounting for pension plan assets

• Explain the reasons for underfunding of defined benefit pension plans

• Explain the elements involved in the accounting for the annual pension expense

• Explore the components of the pension expense

• Review pension plan journal entries and financial statement requirements

• Review the accounting standards governing pension plan accounting

Pension funds in the United States are the largest source of accumulated investment funds. These pension funds control about one fourth of the stock market. Pension costs of an organization constitute one of the largest expenditures of any organization. The organizational liability to provide benefits is huge. Therefore, accounting for these expenditures is a very important organizational responsibility. The responsibility is normally shared between the human resource (HR) department and the accounting department.

The Background

So, pension plans are employer-sponsored programs providing benefits to retired employees for services provided to the employer during working years. From an accounting point of view, there are two entities here: the sponsoring employer and the pension plan itself. The pension plan’s role is to receive contributions from employers, administer the pension plan assets, and make payments to retired employees. When employers contribute to the pension plan, they are funding the plan. Some pension plans are contributory, where an employee bears some of costs of the plan. Other plans are noncontributory, where the employer bears the entire cost of the plan. Note that the pension plan is a separate legal and accounting entity from the sponsoring company.

Individuals accumulate pension funds in an attempt to ensure old-age financial security, when that person will not be able to continue with gainful economic employment. Therefore, the goal is to collect funds so that when the retirement comes around there will be enough of a passive income that will enable retirees and their partners to live a risk-free and comfortable life, without financial concerns. The idea is to replace earned wages with this source of income at retirement.

Living costs do not have to continue at the preretirement levels; pension planners usually target an income-replacement ratio at retirement of around 70% to 80% of the preretirement income. To achieve that goal, individuals save and invest in stocks, bonds, certificates of deposit (CDs), and so on for the sole purpose of saving for retirement.

From an individual’s point of view, because of many uncontrollable factors, effective retirement planning suggests a three-prong approach to old-age income security: private savings and investments, government Social Security (less secure day by day), and employer-provided retirement programs.

This is where employer-sponsored retirement plans come in. Companies sponsor retirement programs to provide employees with a sense of security, to create a satisfied and motivated workforce. Sometimes, based on collective bargaining agreements, employers are obligated to provide retirement benefits.

Employers also are motivated to sponsor retirement programs because of specific tax advantages derived from such programs. Employer-sponsored retirement programs that comply with the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) are called qualified plans because they qualify for tax advantages for the employer. An employer is allowed to take an immediate tax deduction for contributions made into a pension fund within specified limits.

There is also a tax benefit because pension fund assets are accumulated on a tax-free basis. The employee is not taxed on a current basis for contributions they make or are made on their behalf by their employers until they retire and start receiving the retirement benefits. The earnings of the pension funds are also not taxed until benefits are received, which is usually after retirement age. Individual retirement accounts (IRAs), Roth IRAs, and company-sponsored 401(k) plans all are tax-advantaged plans. In other words, contributions to these plans are made with before-tax dollars.

For all these reasons, understanding the accounting, finance, and tax aspects of these programs is a must for all those involved in these plans (that is, those who are responsible for the design, development, and administration of the plans), irrespective of their functional designations or their core competencies.

Participation in employer-sponsored retirement plans in the United States grew from 43 million in 1997 to 86 million in 2007.1 This growth in participation in employer-sponsored retirement plans is directly correlated with the expansion of workers who participated in defined contribution plans (for example, 401(k) plans). Between calendar years 1977 and 2007, the number of participants in defined contribution plans increased 358% compared to a 31% decrease in defined benefit plans. More than two-thirds of workers covered by pension plans are covered by defined-contribution pension plans now. Note, however, that in the United States, 88% of public employees are still covered by a defined-benefit pension plan.2

1 Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration, Statistical Trends in Retirement Plans, August 9, 2010, Reference Number: 2010-10-097.

2 “City employees’ golden years start too soon.” Opinion editorial. Statesman.com. May 7, 2009.

In the private sector, defined benefit plans are certainly on a downward trend with respect to the number of these plans. The reasons are as follows:

• Governmental regulations make defined benefit pension plans administratively complicated.

• Employers do not want the risk of the future with respect to defined-benefit pension plans.

• Long-term “one-employer” employment is not the norm any more.

Although decreasing in numbers, the understanding of the accounting and financing implications of defined benefit pension plans remains an important area of study.

Defined Contribution and Defined Benefit Pension Plans “Defined”

Before we go any further, let’s define the concepts of defined contribution and defined benefit pension plans, which have also been discussed in the previous chapters.

Defined Contribution Pension Plans

In a defined contribution pension plan, the employee contributes an amount voluntarily and regularly on a before-tax basis. The contributions are then invested, based on the employee’s choice, usually in various company-approved investment instruments. There is an annual limit for employee contributions imposed by the government. The limit for employee contributions to a defined contribution plan for the year 2013 is $17,500, up from $17,000 in 2012. The employer normally agrees to match the employee’s contribution by a fixed matching contribution amount. The retirement distributions, upon reaching retirement age, then depend on the size of the accumulated funds in the defined contribution plan.

Defined Benefit Pension Plans

Defined benefit plans promise participants a fixed retirement benefit established by a predefined formula. Factors that are considered in the equation include:

• Years of service

• A compensation amount (either final career average pay or the pay level in the year immediately before retirement)

• Age

Such pension plans have to ensure sufficient funds are available to pay out the defined benefit when disbursement of funds to participants is required.

The Accounting of the Plans

Currently, the basic accounting standards requires that the cost of providing postemployment retirement benefits be recognized when the employee is in active service, rather than when the company actually pays those benefits.3

3 Most Intermediate Accounting books cover the subject of pension plan accounting. The explanation in this book relies primarily, but not exclusively, on material from: Spiceland, J. David, James Sepe, Mark Nelson, and Lawrence Tomassini, Intermediate Accounting, 5th Edition, McGraw-Hill Irwin, New York, 2009.

The Accounting for Defined Contribution Plans

Employers offering defined contribution plans may promise the participant a fixed matching contribution based on the contribution made by the employee. The employer may agree to match each year and deposit the employee contribution into a trust fund based on a formula. The formula might consider factors such as age, length of employee service, and the compensation level of the employee. There are several variations of defined contribution plans, such as money purchase plans, thrift plans, and 401(k) plans. Over 70% of American workers participate in 401(k) plans, with over $2 trillion invested in 401(k) plans. 401(k) plans are now the most commonly used form for the accumulation of retirement savings.

Defined contribution plans can also be tied into company performance, as in profit-sharing plans, 401(k) profit-sharing plans, and incentive savings plans. The retirement benefits that an employee finally collects under a defined contribution plan depend on the amounts contributed to the plan over the years and the investment performance of the funds.

Accounting for defined contribution plans is fairly straightforward. Each year, the employer records a pension expense equal to the amount the organization contributes to the plan. On the income statement, the amount of the contribution is recorded as an operating expense (typically under Selling, General, and Administrative Expenses) in the period the employee provides the employment services to have earned the contribution.

Suppose that a defined contribution plan promises an annual contribution of 5% of the employee’s salary. If the total employee base payroll of those who have elected to participate in the company sponsored 401(k) plan is $10 million, the accounting entry is as follows:

If the employer recognizes and records pension expense on a monthly basis (a more likely scenario), the monthly journal entry will be as follows:

In most companies, the contribution is “matched” with the employee’s base salary. Including the many other elements of cash compensation for matching purposes will introduce too much variability to the pension expense.

In some instances, if the employer chooses to contribute less than the contracted amount to the plan, a pension liability is accrued for these expenses. However, when the employer pays more than the obligated amount to the plan, the employer records a pension asset. On the balance sheet, if the contribution is paid in the same period as the employee earns the benefit, no entries are necessary. If service-related benefits are earned in one period but are expensed in the next, however, the company must record a liability for the amount of the contribution until it is expensed in the income statement. This amount typically falls under Accrued Salary or Other Accrued Expenses.

If the company has recorded a pension payable and makes the contribution at the end of a year, the company then debits Pension Payable (that is, decreases liability) and credits Cash.

Note also that these accounting entries need to be made as and when the employee earns the company contributions by completing the requisite service period. If the plan contract indicates that the company will match up to a certain percentage of employee salary as and when the employee makes his or her contribution, it can be assumed that the service period has been completed. It is important to note that the accounting record keeping is different from the vesting of the employer contributions, which in most plans happens only after the employee has completed a specific employment period. This period in most defined contribution plans is usually three to five years.

Also note that under a defined contribution plan the amount of the employee’s retirement income depends on how well the funds in the employee’s account do over time. The employee bears all the risk of uncertain investment returns. Therefore, investment portfolio strategic choice becomes critical.

Loans under the Plan

IRS regulations allow loans to be taken out from one’s 401(k) accounts. The plan document has to have a provision for such loans. A loan will not be taxable if certain conditions are met.

Generally, a participant may borrow up to 50% of the vested account balance. The loan has to be repaid to the plan within five years, unless the loan was to buy the principal home of the 401(k) account holder. Loans need to be repaid regularly, at least quarterly, over the life of the loan. 401(k) account balances are lowered for loans if there was already a loan outstanding during previous one year before the new loan. Certain participant loans can be considered taxable distributions.

Prior to September 2010, Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) guidance allowed participant loans to be classified as plan investments as per 962-325-45-10. Subtopic 962-325 stated that these loans be generally measured at fair value. In practice, though, most participant loans were carried at their unpaid principal balance plus any accrued but unpaid interest, which was considered a good faith approximation of fair value. And because some parties raised issues with the fair value determination, the standard was revised as of September 2010. These parties questioned whether the standard as written conformed to the requirement to use observable inputs, such as market interest rates, borrower’s credit risk, and historical default rates, to estimate the fair value of participant loans.

So, the current revised standard and guidance indicates that loans to participants be classified as notes receivable from participants. FASB suggested that the guidance now would reduce the amount of time that plan administrators spend on estimating the fair value of participant loans using observable inputs. The classification of participant loans as notes receivable from participants acknowledges that participant loans are unique from other investments in that a participant taking out such a loan essentially borrows against his or her own individual vested benefit account balance.

Also in the discussion about the revised standard it was concluded that it is more meaningful to measure participant loans at their unpaid principal balance plus any accrued but unpaid interest rather than at fair value. Participant loans cannot be sold by the plan. Furthermore, if a participant were to default, the unpaid balance of the loan would reduce the participant’s account, and there would be no effect on the plan’s investment returns or any other participant’s account balance.4

4 Adapted from Financial Accounting Series, Accounting Standards update, No. 2010, September 25, 2010, Plan Accounting–Defined Contribution Pension Plans (Topic 962), Reporting Loans to Participants by Defined Contribution Pension Plans, a consensus of the FASB Emerging Issue Task Force.

401(k) plan’s distribution rules are well-defined in IRS regulations. There are specific rules for hardship withdrawals also.

The Accounting for Defined Benefit Pension Plans

Defined benefit plans are based on a predetermined benefit formula. These benefits usually depend on the employee’s years of service and on the compensation level of the employees close to retirement. The company has to determine what they should contribute today using the time value of money. The funding method used should ensure that sufficient funds are available in the plan to pay the required benefit when the need arises.

In a defined benefit plan, the employees receive the specified benefits when they retire and they are the beneficiaries of the defined benefit trust. The trust’s main objective is the safeguard and proper investment of the accumulated funds so that there is enough to cover the obligations to pay the retirement benefits. Although the pension trust is a separate entity from the employer, the trust assets belong to the employer, and the employer is responsible to pay the defined benefits no matter what the financial position of the trust when benefits have to be paid. So, the employer has to make up any deficiencies in the trust and make up any shortfalls when needed. When there are excesses in the trust, the employer can recapture those excesses either by reducing future funding or taking the excess funds out for other uses. Thus, the employer is at risk with the defined benefit plan because it is their responsibility to ensure that sufficient funds have been accumulated in the defined benefit trust to pay employees’ retirement benefits based on the predetermined formula when needed.

The annual predetermined benefit formula normally starts off with an acceptable income replacement ratio (percentage of preretirement income that will be replaced after retirement).5 The conceptual reasoning behind the income-replacement percentage factor is the percentage of preretirement income the retired person needs to sustain the same standard of living he or she enjoyed before retiring. Logic suggests that the percentage needed is something below 100%. This is because the retired person does not have same types of expenditures in retirement (for example, employment expenses, commuting expenses, child-rearing expenses, and food expenses for a family with children). Therefore, this is usually a policy decision, and in a unionized organization it is often a matter of bargaining negotiations.

5 The theory behind the income-replacement ratio is that a retiring employee can sufficiently manage to live the preretirement standard of living at less than 100% of preretirement income because their living expenses are not as high as they were in their earlier years (no children at home, no employment-related expenses, and so forth).

The annual benefit pension formula consists of various factors: an average employee salary (either final year, or career average salary, or final five- or ten-year salary), years of credited service, and a preestablished percentage factor such as 1.0%, or 1.5%, or 2.5%. The acceptable formula for any organization needs to be derived using an iterative calculation method with the ultimate goal of achieving the policy-driven income-replacement ratio. Additional factors that go into the calculation are mortality estimates and the estimated number of retirement years before the employee dies.

An example of a derived annual defined benefit formula is shown here.

2.5% × final five year average salary × years of credited service = the retirement benefit lump sum amount.

So, an employee who retires after 35 years of credited service and whose final five-year average salary is $150,000 would receive an annual retirement benefit of

2.5% × 35 × $150,000 = $131,250

This works out to be an income-replacement ratio of 87.5%, which is an acceptable income-replacement ratio. Sometimes the calculated lump-sum retirement benefit is (in the preceding example, $ 131,250) distributed via an annuity.

Note that as a result of union negotiations, organizations have inserted different twists to the income-replacement percentage factor. Here is how the California State Teachers’ Retirement System (CalSTRS) describes this income-replacement factor:

The age factor is the percent of final compensation to which you are entitled for each year of service credit, determined by your age on the last day of the month in which your retirement is effective. It is set at 2% at age 60. The age factor is decreased if you retire before age 60 and increased to a maximum of 2.4% if you retire later than age 60. If you retire with at least 30 years of earned service credit, a 0.2% career factor will be added to your age factor, up to a maximum age factor of 2.4%.6

6 California Teachers’ Association Retirement Employee Web site: http://ctainvest.org/home/CalSTRS-CalPERS/about-calstrs/calstrs-retirement-benefit.aspx.

Some organizations call this income-replacement factor a retirement factor; others call it the age factor. Conceptually and theoretically, however, the need for this factor in the defined benefit pension formula is as what has been proposed here: an income replacement percentage (a percentage of preretirement income needed by the retiree to live at the same standard of living he or she enjoyed before retiring). Manipulating this factor to fit self-serving needs just increases the costs of these programs. No wonder private employers are moving away from defined benefit pension plans. This manipulation of the income replacement ratios adds to the “black box” nature of defined benefit pension plans.

Note that in plans where the defined benefit formula uses the final average pay it is possible to make the final average pay artificially high, thus deriving a retirement income level that is higher than preretirement income. One can add overtime pay, accumulated vacation pay, expense reimbursements, and other items to make final pay very high. This results in a high level of defined benefit formula generated retirement income. In these situations, the retiree ends up at an income level that is higher than his or her employment period income level. In essence, they get paid more for not working. The logic of such expenditures is really hard to comprehend. This is an issue that is generating a lot public displeasure with the California Public Service employee defined benefit retirement programs.

But more assumptions, covered with uncertainties, have to be made to accumulate enough funds to be able to distribute the promised benefits using the predetermined formula. Also note that these defined benefits are contractually promised to the retiring employee. The assumptions cover the rate of return on plan assets, employee turnover impacting the number of eligible employees, the actual retirement age when the employee retires (which will impact the length of the retirement period benefits will need to be paid out), inflation rates, salary-increase trends resulting in future salary levels, and interest rates.

All of these unknowns, assumptions, calculations, and the use of a fairly arbitrary defined benefit formula can make defined benefit plans a complicated, uncertain, and very expensive black box.

Defined benefit pension plans have suffered from many structural issues. Because many assumptions are used in the calculations, these assumptions need to be continually adjusted for changing financial conditions. In addition, pension investment targets have not been met regularly. Pension liabilities have increased, but pension assets have not kept pace. All of these factors and many others have caused the decrease in the incidence of defined benefit pension plans, at least in the private sector. Nevertheless, as long as these plans exist, there is a need to study the structure from a finance and accounting perspective.

The calculation of the retirement benefit expenses, obligations, liabilities, and the determination of the formula is the responsibility of an actuary. An actuary is professionally trained and certified in a particular branch of mathematics and statistics. They assign probabilities to future events and calculate the organization’s defined benefits plan assets and liabilities. Employers depend on actuaries for assistance with developing, implementing, and funding of pension plans. However, these calculations involve a lot of subjectivity. Therefore, the actual numbers end up deviating from calculated figures. This necessitates a lot of adjustments to assumptions to ensure that there are sufficient accumulated funds to pay the promised benefits. The actuary works in a challenging environment, in that the accounting estimates of liabilities and expenses need to be created for cash payments that may occur years in the future. Forecasting has many perils.

The risk of the pension-obligation amount increasing from amounts previously calculated is borne by the employer because in a defined benefit plan a fixed predetermined formula is used. Over the years, the uncertainties of the economic environment and the volatility in the financial markets have resulted in changing pension asset balances. Pension investments have not performed as well as expected. The employer’s financial inability to fund the plan regularly has prevented plans from making up funding deficiencies. The shareholders have been confronted with large amounts of unfunded pension liabilities. This has often resulted in weak balance sheets.

Also, falling interest rates and bear markets have wreaked havoc with pension plans, creating a “pensions crisis.” The pension plans of many companies have been severely underfunded, as a result companies, such as United Airlines, have had to file for bankruptcy, stating that it is not possible for them to meet their pension obligations. For all these reasons, FASB reformed pension accounting and in 2006 passed a new standard (SFAS 158), in part to fix the problems with pension accounting. The scene has not been pretty! We discuss the FASB standards governing defined benefit pension plans later in the chapter.

The Accounting for Defined Benefit Plans Explained

From an accounting point of view, the key elements to consider in defined benefit plan accounting are as follows:

• The obligation of the employer to pay the retirement benefit when the employee retires at a future date

• The accumulation of assets in the pension plan to pay retirement benefits from, as, and when the participating employee retires

• The periodic expense of offering and maintaining a pension plan

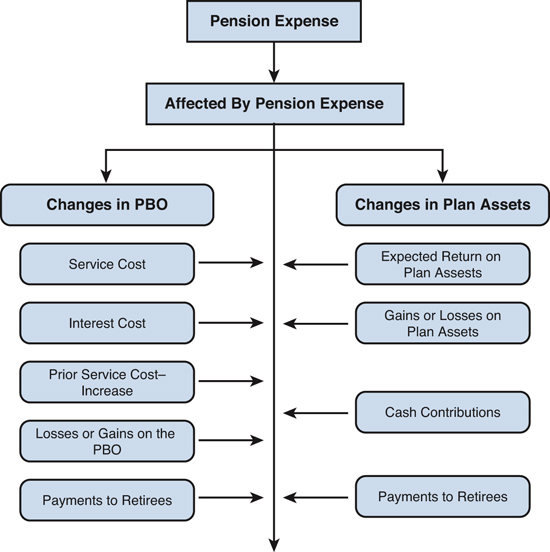

Currently, the expense items are not reported individually in the financial statements, but the pension obligation is netted against pension assets, and the net amount has to be shown as a line item on the balance sheet. The individual balances are reported separately in the footnote disclosures. Also, a calculated pension expense needs to be shown as an operating expense on the income statement. The expense is a composite of the periodic changes in both the plan obligations and the plan assets. The components of the pension expense are as follows:

• The service cost related to employee service during a specific period.

• The interest accrued on the pension liability during a given period.

• The impact of the return on plan assets, on the balances. If this is negative, it reduces the pension expense. The opposite is true if the returns are positive.

• The increased impact of the amortization of prior service cost attributed to employee service.

• Either the positive or negative impact of the losses or gains from revisions in the pension liability or from investing the plan assets.

We now take a closer look at the pension obligation and the pension asset. Then we review the components of the pension expense.

The Pension Benefit Obligation

The employer’s pension obligation is the deferred obligation the employer has to its employees for the service they have rendered satisfying the terms of the pension plan. There are various ways of measuring that obligation.

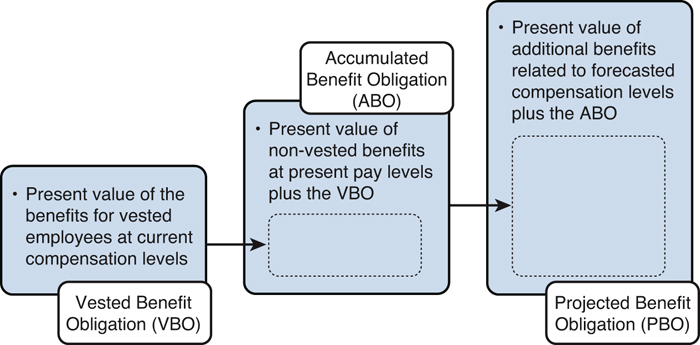

The different measurement methods for the benefit obligations are as follows:

• The vested benefit obligation (VBO): This is the amount of the accumulated benefit obligation that plan participants are entitled to receive regardless of whether they discontinue their current employment with their present employer or not (the vested pension benefits). Pension plans usually require a minimum years of service before the employee attains the vested benefits status. The calculation is made at the current salary levels. Since 1989, the plan provisions should indicate that benefits must vest (1) completely within five years or (2) 20% within three years with another 20% vesting each subsequent year until full vesting within seven years.

• The accumulated benefit obligation (ABO): This is the amount estimated by the actuary of the discounted present value of the retirement benefits earned by employees as of the valuation date, using the current compensation level of those employees and the plan’s pension formula. The measurement here is based on both the vested and nonvested years of service. The current salaries are used in this calculation.

• The projected benefit obligation (PBO): The amount the actuary calculates as the present value of vested and nonvested benefits accrued to date based on all the employees’ projected salaries at retirement. The accounting profession has adopted the projected benefit obligation (PBO) as the measure for overall pension liability of an organization.

Another way of looking at the projected benefit obligation is the build-up method. Three components form the total pension benefit obligation. The summary given in Exhibit 10-1 should further clarify the three elements of the total pension benefit obligation.

Exhibit 10-1. The Build-up Method for the PBO

A Note about the Pension Benefit Guarantee Corporation

The Pension Benefit Guarantee Corporation (PBGC) was established under the ERISA legislation as a governmental insurance entity to which qualified plans pay a premium for each participant enrolled in a plan. The role of the PBGC was to serve as a payer of last resort for retirement benefits in case of a plan default due to a bankruptcy. The maximum pension benefit guaranteed by PBGC is set by law and adjusted yearly. For plans that end in 2011, under PBGC’s insurance program for single-employer plans, workers who retire at age 65 can receive up to $4,500 per month (or $54,000 per year).7 PBGC’s role is similar to the role that the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) plays in the banking sector. For 2011, the premium rate is $9 per participant for multiemployer plans; single-employer plans pay $35 per participant plus $9 for each $1,000 of unfunded vested benefits. The per-participant rates are indexed for inflation.8

7 “Maximum monthly guarantee tables.” Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation.

8 Federal Register, Vol. 72, No. 230, November 30, 2007, Notices 67765.000.

Note that during fiscal year 2010 the PBGC paid $5.6 billion in benefits to participants of failed pension plans. That year, 147 pension plans failed, and the PBGC’s deficit increased 4.5% to $23 billion. The PBGC has a total of $102.5 billion in obligations and $79.5 billion in assets.9 Not a pretty picture!

9 “Insurer reports wider annual deficit,” Washington Post, November 16, 2010.

The Projected Benefit Obligation

Note the defined benefit formula might indicate that the final average salary or the final-year salary needs to be used. To calculate the projected benefit obligation, the actuary projects the salary levels using an estimate of future salary increases. Using the salary projection, the actuary creates an estimate of the final average pay or the final-year salary. The projections for salary levels are used to project the benefit obligation liability.

Let’s look at an example of the calculations for the different pension obligation measures using ten employees.

Let’s suppose that the Safari Group hired ten employees in 1995. The company has a defined benefit pension plan with the predefined benefit formula as follows:

2.0% × Final year salary × Years of credited service

Let’s now say that all ten employees are scheduled to retire in 2030 after 35 years of service. These employees’ retirement period is estimated to be on the average 30 years (we are taking an average here for simplicity; in actuality, the actuary would do the calculation separately for each employee). At the end of 2005, after ten years of service, the base salaries of the ten employees totaled $700,000. The projected salary at retirement for the ten employees totaled $1,465,645. The average salary increase assumption being used here is 3.0% per year. The interest rate assumption for this example is 4%.

So, what is the projected benefit obligation for the ten employees?

1. First, determine retirement benefits earned to date (after ten years of services at the end of year 2005):

2.0% × 10 years × $1,465,645 = $293,129 (or $ 29,313 per person per year)

2. Next, find the present value of the retirement benefits as of the retirement date:

n= 30 years; i =4%; $293,129 × 17.29203* = $5,068,795 ($506,880 per person)

Retirement benefits are scheduled to be paid out for 30 years.

*Note 1: Using appropriate PV tables discount factor for 30 years; present value of an ordinary annuity of $1.

3. Next, find the present value of retirement benefits as of the current date:

n = 25 years; i = 4%; $5,068,795 × .37512* = $1,901,406 ($190,141 per person PBO at the end of year 2005)

*Note 2: Using appropriate PV tables discount factor for 25 years; present value of $1.

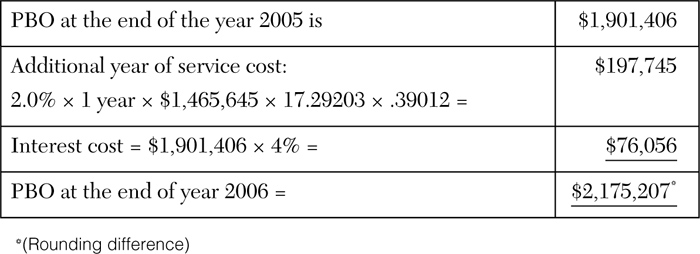

From year to year, the estimate for the projected benefits obligation changes. This is because the actuary has to add an additional year of service and the participating employee is one year closer to retirement. So, the present value increases. The other factors that change the PBO estimate from year to year are the gains or losses on pension assets, prior service cost, and the benefits paid to employees who retired during the current year.

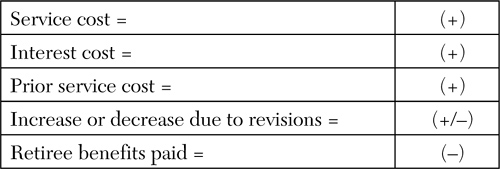

So, the PBO changes because of the following:

• Service cost: At the end of a year, an additional year has expired for pension obligation calculation purposes. So, the change in the pension obligation reflects the increase in the PBO estimate resulting from the additional year of service. Another year of service will change the calculations in this manner:

At the end of the year 2006, the calculations demonstrated for the ten employees will change in this manner:

1. 2.0% × 11 years × $1,465,645 = $322,442 (or $32,244 per person per year)

2. n = 30 years, i = 4.0%; $322,442 × 17.29203* = $5,575,677 (or $557,568 per person)

*Note 3: the same discount factor for 30 years shown in the previous calculation.

3. n = 24 years, i = 4.0%; $5,575,677 × .39012* = $2,175,183 ($217,518 per person PBO at the end of the year 2006)

*Note 4: Using appropriate PV tables discount factor for 24 years; present value of $1.

The PBO has increased from $1,901,406 to $2,175,183; an increase of $273,777 ($27,378 per person).

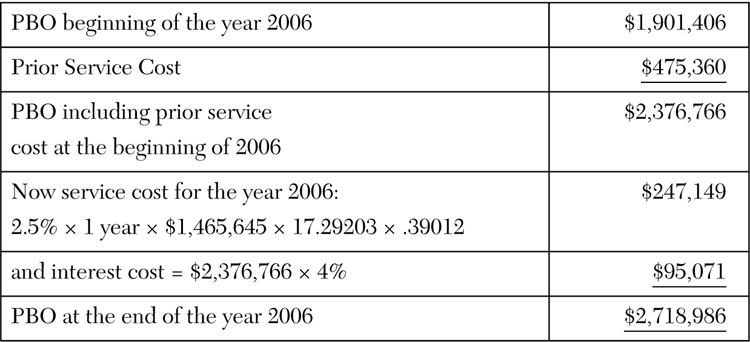

• Interest cost: Another reason the PBO estimate increases is because of interest cost. Because the PBO is a liability, interest on the liability changes from year to year. This estimate is calculated by multiplying the discount rate by the PBO balance existing at the beginning of the year. The calculations in Exhibit 10-2 demonstrate that PBO changes are reflecting an additional service year and the interest cost for the ten employees.

Exhibit 10-2. PBO at the end of 2006

• Prior service cost: Sometimes the sponsoring organization might amend the plan during a given year by changing the plan formula. When the new defined benefit formula is applied during the current year, the PBO estimate changes. The estimate going forward might either increase or decrease. Plan designers might designate these benefit plan changes to be on a proactive (going forward) or retroactive (going back) basis. The PBO estimates made during the current period can change based on the retroactive or the proactive designation. This change element is called the prior service cost change. To demonstrate how the plan changes affect the pension benefit obligation when changes are made on a retroactive basis, consider the calculation for the ten employee example shown here.

Let’s say in our example plan design changes the benefit formula (changed January 2, 2006) as follows:

2.5% × Years of credited service × Final year pay (instead of 2%)

Now we see how the formula change affects the PBO:

1. 2.5% × $1,465,645 × 10 years = $366,411

2. $366,411 × 17.29203* = $6,335,990

3. $6,335,990 × .37512* = $2,376,766

Prior service cost then is = $2,376,766 – $1,901,406 = $475,360 ($47,536 per person)

*Note 4: From PV tables discount factors (see previous explanations).

So, now we see the PBO at the end of the year 2006 as shown in Exhibit 10-3.

Exhibit 10-3. PBO at the end of year 2006 with formula change

$2,718,986 is changed from $2,175,207 because of formula change.

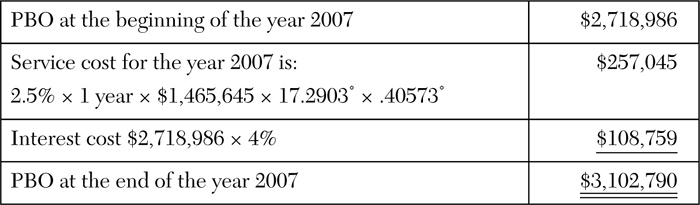

Let’s assume that in our example it is now year 2007. The end of year 2007 calculation is (for the ten person case) as shown in Exhibit 10-4.

Exhibit 10-4. PBO at the end of 2007

*Note 5: From PV tables discount factors for 30 years and 23 years, respectively.

• Gain or loss on the PBO: If the actuary revises his or her calculation assumptions during the current year, this might result in a gain or a loss. The actuary might change the following assumptions:

• A change of life expectancy

• The assumption as to when retirement will actually occur

• A change made in the assumed discount rate

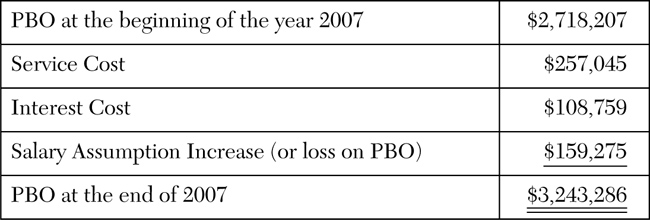

If any of these assumption changes are executed, the PBO obligation can show a gain or a loss. Let’s see an example of this factor in the ten-employee example we are using.

Now let’s assume that a change is made for the final-year salary from $1,465,645 to $1,550,000 in the year 2007.

The PBO with the revision will be as follows

2.5% × 12 years × $1,550,000 = $465,000

$465,000 × 17.29203* = $8,039,990

$8,039,990 × .40573* = $3,262,065

*Note 6: From PV tables discount factors for 30 years and 23 years, respectively.

The PBO increase because of the revised assumption to final-year salary by = $3,262,065 – $3,102,790 = $159,275 ($15,928 per person).

Exhibit 10-5 shows a summary of the change.

Exhibit 10-5. PBO end of year 2007 with Salary assumption increase

• Payment of retirement benefits: This is the change in the PBO that takes place when employees retire during the current period and retirement benefits are paid out to these employees resulting in reducing the pension benefit obligation.

So, in summary, the PBO changes because of the factors listed in Exhibit 10-6.

Exhibit 10-6. Factors affecting PBO

Aggregate Calculation

Our example here has focused the calculations for ten employees only for ease of understanding. Normally, the actuary makes the estimates and projections for the entire employee population covered under the defined benefit pension plan.

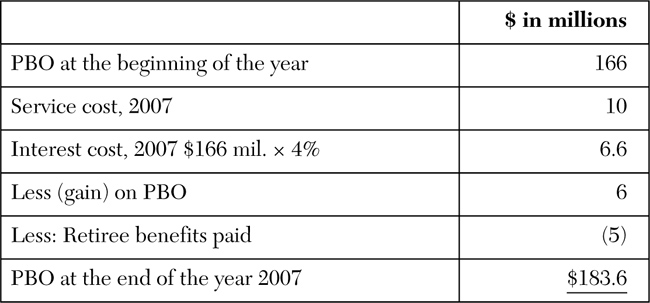

Let’s assume that the aggregate (total of all employees) calculations for the Safari Group are as shown in Exhibit 10-7. The changes in the PBO for the Safari Group during the year 2007 are shown; all amounts are assumed.

Exhibit 10-7. Aggregate PBO Calculations

Pension Plan Assets

Calculation of the pension obligation is one thing, regardless of whether the obligation is the vested benefit obligation, or the accumulated benefit obligation, or the projected benefit obligation. The other thing is having enough funds to pay the obligations when necessary.

So, the defined benefit plan has to accumulate enough assets to be able pay the benefit obligations. The balances in the pension plan assets have to be reported in the footnotes of the company’s financial statements.

A trustee holds the assets of the pension plan. The pension plan trustee accepts the employer’s contribution to the plan and invests the funds accumulated and pays out pension benefits to retired employees. The trustee is normally a bank or a company that provides services as a pension plan trustee. The trustee, on the advice of a pension plan advisor, invests pension plan assets in stocks, bonds, and other types of income-producing assets. The investment advisor or manager influences pension plan investments by directing the trustee to invest the funds as advised.

The investment advisor or manager acts in accordance and within the structure developed by a retirement committee. The retirement committee sets up an appropriate retirement funds investment policy. This committee also establishes the ongoing funding policy for the pension plan. For example, they might lay out a policy that states that the company will fund each year’s incremental service cost and also a portion of the prior year’s service cost if the plan formula is or has been changed. They will also advise whether retroactivity will be applied. The goal is to ensure that the pension asset balances are sufficient to be able to pay the benefits as and when they become due. The pension plan assets fluctuate based on dividends earned, interest, and market-price appreciation.

Each year, the actuary calculates whether the company needs to contribute more funds to be set aside to pay the benefits. To do this, they need to estimate an expected rate of return that the accumulated funds will produce. This is because the higher the expected return, the more funds will be available to pay out in benefits and the less current contributions will be needed from the company. If the estimate of the expected rate of return does not materialize, the company might need to make additional contributions from general funds to ensure that there are enough pension plan assets to meet the obligations. In the recent past, rate-of-return estimates have been around 3% to 9%, with 6.0% being the median percentage. These are the estimates actuaries have used.

So, during any given calculating period, if the actuary calculates that the plan assets will not suffice to meet the projected benefit obligation, the pension plan is underfunded. Over the past few years, the reality has been that defined benefit plans have remained underfunded. The reasons for underfunding have been many, including the main ones listed here:

• Because of limited cash availability, companies have been unable to continue funding pension plans. Therefore, the underfunding condition has been difficult to remove. The inability to replenish the plan with additional contribution funds got aggravated over the years, and many companies therefore have had to convert defined benefit plans to defined contribution plans or completely disband defined benefit pension plans.

• From year to year, actuaries have found that their assumptions for plan calculations have needed to be revised (and mainly downward). This downward adjustment has been made specifically for the rate-of-return assumption, mainly because investments have suffered from increased market volatility.

• Union pressure to change benefit formulas upward. This has increased the projected pension benefit obligation and increased the underfunding situations.

With the passage of ERISA, minimum funding standards have been introduced to protect plan participants. But the bust and boom scenarios of the stock market have created projected benefit obligation overfunding and underfunding. In addition, companies have diverted pension funds when there has been overfunding situations. The diversion of funds has reduced the long-term viability of the plans over an extended period of time. This has resulted in many firms being in an underfunded situation. Sponsoring companies have had financial troubles, and therefore the pension plans were disbanded. PBGC insurance got triggered. Excessive demands on the PBGC have also negatively impacted the whole system. The PBGC benefit amount in case of a sponsor disbanding their plan is $3,500 a month. Often, this payment is much less than the promised benefit. And because calls to PBGC to pay more and more retirement benefits for bankrupt plans have increased, PBGC has had to increase per-participant premiums. Thus, in a circular manner, the defined benefit plan environment has become problematic, leaving companies no other option than to discontinue defined benefit pension plans and to introduce defined contribution plans instead.

But, there is still no requirement to report pension plan obligations or the accumulated pension plan assets directly in the financial statements in any reporting period. Organizations need to report only the net difference between the two amounts, either as net pension liability or a net pension asset depending on the funding status of the plan.

Let’s now demonstrate aggregate calculations with the Safari Group example.

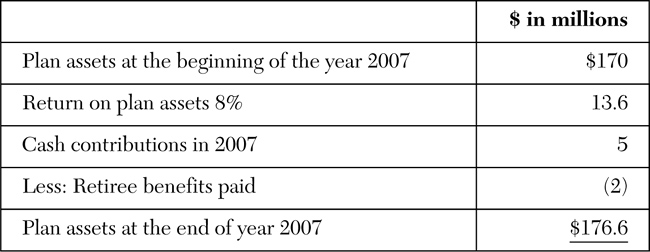

The Safari Group decides that it will fund a portion of each year’s service cost. Let’s say that the retirement committee has decided to fund the plan with $5 million for the year.

Let’s assume that the plan assets at the beginning of the year 2007 were $170 million. The expected return was 7%, but the actual return in 2007 was 8%. And let’s assume that the company paid out $2 million in retirement during the year 2007.

Exhibit 10-8 shows the plan’s assets at the end of 2007.

Exhibit 10-8. The Plan Assets at Year’s End 2007

And let’s assume that the PBO at the end of the year for the entire employee population was $183.6, as indicated in Exhibit 10-7. The plan is now underfunded. Companies are required to recognize on their balance sheets the underfunded or overfunded status of their defined benefit plans. This status is recorded on the balance sheet as the netted amount of the fair values of plan assets and the projected benefit obligation.

The Pension Expense

The pension expense relates directly to the changes in the projected benefit obligation and the change in plan assets discussed in the previous sections. Once calculated, the pension expense is directly reported as a period expense on the current period’s income statement. The pension expense reported on the income statement is a combination of changes that took place in the pension obligation, the pension plan assets, and the current-year increase in the employer’s obligation attributed to the employee service during the current reporting year. The pension expense then is considered as a current period compensation expense along with other total compensation expenses such as wages, salaries, sales commissions, incentives, bonuses, and the various other forms of compensation discussed in this book. So, in essence, the accounting process is matching all the forms of total compensation with the services provided by employees during that specific time period.

Exhibit 10-9 explains the derivation of the pension expense.

Exhibit 10-9. Factors affecting the Pension Expense

We will now discuss each component of the pension expense:

• Service cost: This is the change in the PBO attributable to the employee service that was provided during the current reporting year for which the financial statements are being prepared. More precisely, the service cost is said to be the actuarial present value of retirement benefits based on a predetermined benefit formula applied to the employee service rendered during the past year. FASB has adopted a benefits/year-of-service actuarial method. The important point to note here is that the service cost or the present obligation has to be calculated using the future compensation levels

• Interest cost: This is the cost that is calculated by multiplying the actuary’s discount rate (interest rate) by the beginning-year projected benefit obligation. This is the interest for the period on the PBO outstanding during the period. FASB states that the assumed discount rate should reflect the rates at which pension benefits are expected to be settled. Companies usually look for rates of return on high-quality fixed-income investments currently available in the market. Note that the interest cost is combined with the other components of the pension expense and reported as part of the pension expense and not shown separately in the income statement as an interest expense.

• Return on plan assets: The return on plan assets is derived from investing the plan assets in various investment instruments, such as, stocks, bonds, and various other securities. But each year there has to be a reconciliation of the expected rate of return used versus the actual rate of return achieved. This is because the employer contributions and actual returns on the accumulated pension assets increase the pension plan assets.

We know that if the plan assets are invested wisely and the assets accrue positive returns that the employer sponsoring the plan does not have to contribute as much to the plan. Positive returns reduce the cost of the pension plan, and so the amount to be reported as pension expense will be reduced by positive investment returns. The actual returns earned on the plan’s assets increase the fund balance and as a result reduce the employer’s cost of providing employee pension benefits.

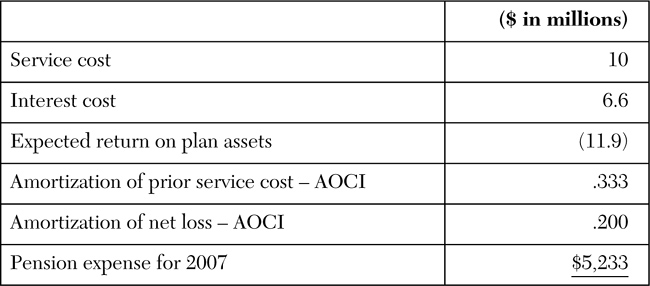

In the Safari Group example, the expected return is used in deriving the pension expense. In the example, the expected rate of return was 7% on the beginning of the year plan assets of $170 million. $170 million × .07 = $11.9 million.

Then there is the question of how and when to reconcile differences between the actual rate of return and expected rate of return that was used in the estimates. FASB has required that the expected rate of return be used in the calculation of the pension expense. This seems counter logical because the pension expense is reduced by the actual rate of return on plan assets and the charge to pension should reflect the actual return. But FASB guidance says otherwise. The difference between the actual rate of return and the expected rate of return is considered a gain or a loss on plan assets.

• Amortization of prior service cost: If a plan sponsor for whatever reason changes the pension benefit formula during a given reporting year, the actuary has to change the pension benefit obligation to reflect that change. Sometimes a plan sponsor changes the benefit formula during a given year but because of the terms of a union contract or for just good employee relations the plan sponsor agrees to retroactively give credit for prior service years. Of course, such action might not work with the employee if the employer revises the formula downward. In this case, the expedient path would be that the reduced formula would take effect only going forward. In any case, normally the formula is revised upward, with the pension benefit obligation increasing.

But how does the accounting convention treat the increased pension obligation? The increased obligation can be reported entirely as a current period expense in the year of the plan amendment. But under FASB, the increased costs associated with plan amendments cannot all be carried to expense in the year of the amendment but must be amortized. The time period to amortize these costs is over the time the employees who benefit from the changes will work for the company.

Also note that under FASB the unamortized balance of prior service cost is not an asset, although it is being amortized, but it is carried as a shareholder equity account under accumulated other comprehensive income (AOCI).

Suppose, for example, that in aggregate the prior service cost (which was explained in the ten-employees example) is $5 million at the beginning of 2007. Also assume that the average service period remaining for all employees at Safari Communications is 15 years. Then, the current-year pension expense for the amortization of prior-year service cost will be as follows:

$5 million / 15 years = $333,333, and this will be the number that will be used as part of this year’s pension expense.

• Amortization of a net loss or net gain: Gains or losses occur when the assumptions used to calculate both the pension obligations and the pension assets are revised during the current year. Accounting conventions, like the prior service costs, do not allow the entire gain or loss resulting from updating the pension obligation to be reported on the income statement as a pension expense in the year the changes are made. However, it is reported as other comprehensive income on the statement of comprehensive income. Then it is carried as Net Loss – AOCI or a Net Gain – AOCI depending on whether there are greater losses or gains. These amounts are reported as part of AOCI on the balance sheet in the Shareholder’s Equity section.

A case can be made that these gains or losses should be shown as part of the current-year earnings because these gains or losses affect the net cost of providing the defined benefit plan. But FASB designates that the income statement recognition for both the gains and losses be delayed.

The current delayed recognition of gains or losses achieves income smoothing, but this stance is not true to the accounting principle, referred to as the matching principle. But the practical justification for the delay principle is the fact that over time, gains and losses cancel each other out. And if that were the case, why subject corporate income statements to nonoperational fluctuations via the changes in the pension benefit account?

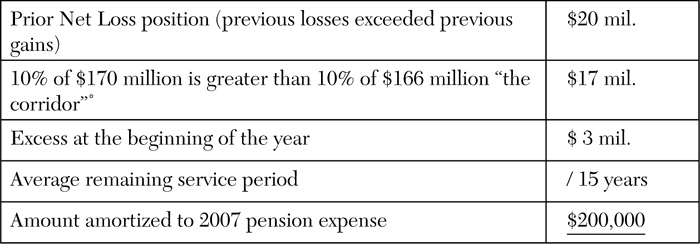

So, in any year when the gain or loss is excessive, there needs to be recognition in the pension expense account.

SFAS 87 arbitrarily assigns a 10% threshold to the excess evaluation. When the PBO or the pension asset gain or loss at the beginning of the year is more than the 10% threshold, then there needs to be recognition. This 10% threshold is called a corridor. The corridor states that 10% of either the PBO or the pension asset, whichever is higher at the beginning of the year, will be taken as a pension expense. The excess is charged to income over a period of time and not all at once. The amount of the excess that is charged to income is the excess divided by the average remaining service period of all active employees who would be scheduled to receive retirement benefits. The calculation of the amortized amount for the amortization of a net loss or net gain is shown in Exhibit 10-10.

Exhibit 10-10. The Corridor Calculation

Let’s say that the Safari Group had a cumulative net loss position.

*Note 7: In the example, the aggregate numbers were $170 million plan assets at the beginning of the year and $166 million PBO at the beginning of the year.

So, for this example, the summary of pension expense in 2007 is as shown in Exhibit 10-11.

Exhibit 10-11. Summary of Pension Expense in 2007

Note that numbers for Exhibit 10-11 came from Exhibit 10-7.

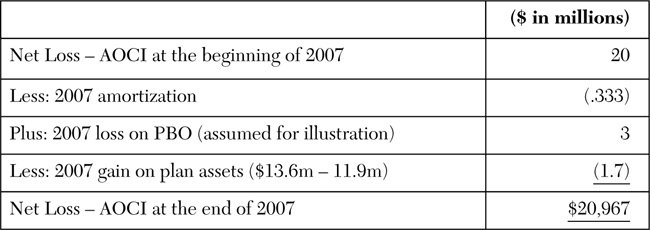

So, the Net Loss – AOCI account at the end of 2007 will be as shown in Exhibit 10-12.

Exhibit 10-12. Net Loss – AOCI Account

The Accounting Record-Keeping

Here we include a brief review of the required journal entries for pension accounting. As discussed previously, gains or losses resulting from (1) changing PBO assumption and (2) from the return of assets being either higher or lower than expected are not immediately charged to pension expense in any given year. They are reported as part of other comprehensive income (OCI) on the statement of comprehensive income.

If a loss occurs, because of a change in assumption, an increase (credit) in the PBO account is recorded, and an associated decrease (debit) is recorded to the OCI account. If a change in assumption causes a gain in the PBO account, a debit is recorded, and a credit is recorded to the OCI account.

If there is a gain because the actual returns were higher than the expected return, the plan assets increase. The increase in the plan assets is the difference between the expected and the actual return. In this case, the PBO account is debited and a credit entry is made to the OCI account reflecting the gain. If the actual return was the less-than-expected return, a debit entry is made to the OCI account and a credit to plan assets is recorded.

There is also a need to make a change in the prior service account for any new prior service cost when it occurs. For this, a debit entry is made to Prior Service Cost – OCI (increase because of plan revision) and a credit entry is made to the PBO account.

As indicated, prior service cost as well as gains or losses when they occur are reported as OCI on the statement of comprehensive income. The OCI items accumulate as Prior Service Cost – AOCI and net loss (or gain) – AOCI. When this account is amortized, the amortization amounts are also reported in the Statement of Comprehensive Income. Amortization reduces Prior Service Cost – OCI and Net Loss – AOCI. Because these accounts have debit balances, the amortization amounts are credited. Net gain amortization is debited because net gain has a credit balance.

The funded status of the plan is reported in the balance sheet, and that is the difference between the PBO and the plan assets.

When the company contributes additional funds to the plan, the plan assets are debited and cash is credited.

To record a pension expense, the following entries need to be made.

1. Pension expense (debit).

2. Plan assets (expected return on assets) (debit)

3. Amortization of prior service cost – OCI (for a given year) (credit)

4. Amortization of net loss – OCI (for a given year) (credit)

5. PBO (service cost + interest cost) – credit (an increase)

On a typical balance sheet, the Net Pension Liability (which has been explained before) is reported in the Liabilities section of the balance sheet. And in the Shareholder’s Equity section, you would find the following accounts reported under Accumulated Other Comprehensive Income:

• Net Loss – AOCI

• Prior Service Cost – AOCI

ERISA, FASB, and American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) have established requirements for financial statement issuance for defined benefit pension plans. We briefly review these required statements in the next section.

Statement of Accumulated Plan Benefits for Defined Benefit Pension Plans

In addition to other reporting and disclosure requirements, defined benefit pension plans are required to report the actuarial present value of accumulated plan benefits for the beginning and the ending of the plan year. In addition, the change to the present value of accumulated benefits (PVAB) from year to year has to be reported. Note that this amount is not the actual plan liability. The PVAB reflects only those benefits that have accumulated as of a specific date. The PVAB can be reported on the same page as the Statement of Net Assets Available for Plan Benefits, or it can be reported in a separate statement. It can also be reported in a footnote. The report needs to show numbers for (1) vested benefits for participants currently receiving benefits, (2) other vested benefits, and (3) nonvested benefits. The method of calculation and significant assumptions used to calculate the PVAB needs to be reported in a footnote.

Statement of Changes in Accumulated Plan Benefits for Defined Benefit Pension Plans

Here information on the changes in the PVAB from the previous to the current reporting period can be presented as a separate financial statement or in the footnote. This can be presented in a narrative or a reconciliation format. Any changes in accumulated plan benefits made during the plan year needs to be reported as of that year, and there is no requirement for retroactive reporting. Any significant factor, whether affecting independently or in conjunction with other factors, needs to be identified. Minimum disclosure requirements for this statement include (1) plan amendments, (2) changes in the nature of the plan (for example, resulting from spinoffs and mergers), and (3) changes in actuarial assumptions. Other changes in accumulated benefits and benefits paid, including actuarial gains or losses, as a result of changes in the discount rates need to be disclosed as well.

Reporting Requirements for Defined Contribution Plans

In defined contribution pension plans, amounts contributed by participants and the investment results of the accumulated funds and forfeitures allocated all affect the plan balances.

The required disclosure requirements are as follows:

• Amount of unallocated assets

• The basis used to allocate assets to participant accounts when there is a difference in the allocation basis from that used to record assets in the financial statements

• Net assets and significant components of the changes in net assets for nonparticipant-directed investment programs

• Amounts allocated to participants who have withdrawn from the plan

• Nonparticipant-directed investments that represent more than 5% of total net assets

Note also that an auditor’s report on employee benefit plan financial statements is normally included as part of the annual reports as per ERISA standards. These audit reports need to conform to requirements of SFAS No. 58 – Reports on Audited Financial Statements.

Accounting Standards Affecting Pension Plans

In September 2006, SFAS 158, Employers’ Accounting for Defined Benefit Pension and Other Postretirement Plans – An Amendment of FASB Statements No. 87, 88, 106, 132 (R), was issued. This statement significantly changed balance sheet reporting of defined benefit pension plans.

The instability in the defined benefit pension plan environment resulted in FASB reforming pension accounting. With the passage of SFAS 158, this was accomplished. Before SFAS 158, certain events, such as plan amendments or actuarial gains or losses, were granted delayed balance sheet recognition. Therefore, the plan’s funded status (plan assets minus obligations) was rarely reported on the balance sheet. SFAS 158 requires companies to report the plan’s funded status either as an asset or a liability on the balance sheets.

The framework for pension accounting under Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) was first established with the standard SFAS 87. The focus of SFAS 87 was obtaining a stable and permanent measure of the pension expense. Pension expense was included in net income – net periodic pension cost. This smoothed out the volatile components of the pension costs (for example, actuarial gains and losses, prior service, and actual return on planned assets). To connect the pension to the balance sheet, SFAS recognized the cumulative net periodic cost (accrued or prepaid pension cost) on the balance sheet instead of the actual funded status of the plan.

SFAS 158 improves financial reporting by more clearly communicating the funded status of the defined benefit pension plans. Under SFAS 158, companies with defined benefit pension plans must recognize the difference between the plan’s projected benefit obligation and the fair value of the plan assets, either as an asset or a liability. The unrecognized prior service costs and actuarial gains and losses that were previously reported in the footnotes are now recognized on the balance sheet, with an offsetting amount in accumulated other comprehensive income in shareholder’s equity.

The pension expense included in net income remains SFAS 87’s net periodic pension cost. This remains a function of service cost, interest cost, expected return on pension plan assets, and amortization of unrecognized items. However, actuarial gains or losses and prior service costs that arise during a period are recognized as part of comprehensive income amortization of actuarial gains or losses; prior service costs require reclassification adjustment to comprehensive income.

Key Concepts in This Chapter

• Income replacement ratio

• Defined contribution pension plans

• Loans from defined contribution pension plans

• Defined benefit pension plans

• FASB standards for the accounting of pension plans

• Pension benefit obligation

• Accumulated benefit obligation

• Projected benefit obligation

• Pension Benefit Guarantee Corporation

• Service cost

• Interest cost

• Prior service cost

• Gain or loss on the PBO

• Pension plan assets

• The pension expense

• Return on plan assets

• Amortization of prior service cost

• Amortization of a net loss or net gain

• Statement of accumulated plan benefits

• Changes to accumulated plan benefits

• Reporting requirements for defined benefit pension plans

• Actuary’s role in costing defined benefit pension plans