1. The Foundations of Contemporary Approaches to Experiential Learning

The modern discovery of inner experience, of a realm of purely personal events that are always at the individual’s command and that are his exclusively as well as inexpensively for refuge, consolidation and thrill, is also a great and liberating discovery. It implies a new worth and sense of dignity in human individuality, a sense that an individual is not merely a property of nature, set in place according to a scheme independent of him . . . but that he adds something, that he makes a contribution. It is the counterpart of what distinguishes modern science, experimental hypothetical, a logic of discovery having therefore opportunity for individual temperament, ingenuity, invention. It is the counterpart of modern politics, art, religion and industry where individuality is given room and movement, in contrast to the ancient scheme of experience, which held individuals tightly within a given order subordinate to its structure and patterns.

—John Dewey, Experience and Nature

Human beings are unique among all living organisms in that their primary adaptive specialization lies not in some particular physical form or skill or fit in an ecological niche, but rather in identification with the process of adaptation itself—in the process of learning. We are thus the learning species, and our survival depends on our ability to adapt not only in the reactive sense of fitting into the physical and social worlds, but in the proactive sense of creating and shaping those worlds.

Our species long ago left the harmony of a nonreflective union with the “natural” order to embark on an adaptive journey of its own choosing. With this choosing has come responsibility for a world that is increasingly of our own creation—a world paved in concrete, girded in steel, wrapped in plastic, and positively awash in symbolic communications. From those first few shards of clay recording inventories of ancient commerce has sprung a symbol store that is exploding at exponential rates, and that has been growing thus for hundreds of years. On paper, through wires and glass, on cables into our homes—even in the invisible air around us, our world is filled with songs and stories, news and commerce interlaced on precisely encoded radio waves and microwaves.

The risks and rewards of mankind’s fateful choice have become increasingly apparent to us all as our transforming and creative capacities shower us with the bounty of technology and haunt us with the nightmare of a world that ends with the final countdown, “. . . three, two, one, zero.” This is civilization on the high wire, where one misstep can send us cascading into oblivion. We cannot go back, for the processes we have initiated now have their own momentum. Machines have begun talking to machines, and we grow accustomed to obeying their conclusions. We cannot step off—“drop out”—for the safety net of the natural order has been torn and weakened by our aggressive creativity. We can only go forward on this path—nature’s “human” experiment in survival.

We have cast our lot with learning, and learning will pull us through. But this learning process must be reimbued with the texture and feeling of human experiences shared and interpreted through dialogue with one another. In the over-eager embrace of the rational, scientific, and technological, our concept of the learning process itself was distorted first by rationalism and later by behaviorism. We lost touch with our own experience as the source of personal learning and development and, in the process, lost that experiential centeredness necessary to counterbalance the loss of “scientific” centeredness that has been progressively slipping away since Copernicus.

That learning is an increasing preoccupation for everyone is not surprising. The emerging “global village,” where events in places we have barely heard of quickly disrupt our daily lives, the dizzying rate of change, and the exponential growth of knowledge all generate nearly overwhelming needs to learn just to survive. Indeed, it might well be said that learning is an increasing occupation for us all; for in every aspect of our life and work, to stay abreast of events and to keep our skills up to the “state of the art” requires more and more of our time and energy. For individuals and organizations alike, learning to adapt to new “rules of the game” is becoming as critical as performing well under the old rules. In moving toward what some are optimistically heralding as “the future learning society,” some monumental problems and challenges are before us. According to some observers, we are on the brink of a revolution in the educational system—sparked by wrenching economic and demographic forces and fueled by rapid social and technological changes that render a “frontloaded” educational strategy obsolete. New challenges for social justice and equal opportunity are arising, based on Supreme Court decisions affirming the individual’s right of access to education and work based on proven ability to perform; these decisions challenge the validity of traditional diplomas and tests as measures of that ability. Organizations need new ways to renew and revitalize themselves and to forestall obsolescence for the organization and the people in it. But perhaps most of all, the future learning society represents a personal challenge for millions of adults who find learning is no longer “for kids” but a central lifelong task essential for personal development and career success.

Some specifics help to underscore dimensions of this personal challenge:

![]() Between 80 and 90 percent of the adult population will carry out at least one learning project this year, and the typical adult will spend 500 hours during the year learning new things (Tough, 1977).

Between 80 and 90 percent of the adult population will carry out at least one learning project this year, and the typical adult will spend 500 hours during the year learning new things (Tough, 1977).

![]() Department of Labor statistics estimate that the average American will change jobs seven times and careers three times during his or her lifetime. A 1978 study estimated that 40 million Americans are in a state of job or career transition, and over half these people plan additional education (Arbeiter et al., 1978).

Department of Labor statistics estimate that the average American will change jobs seven times and careers three times during his or her lifetime. A 1978 study estimated that 40 million Americans are in a state of job or career transition, and over half these people plan additional education (Arbeiter et al., 1978).

![]() A study by the American College Testing Program (1982) shows that credit given in colleges and universities for prior learning experience has grown steadily from 1973–74 to 1980–82. In 1980–82, 1¼ million quarter credit hours were awarded for prior learning experience. That learning is a lifelong process is increasingly being recognized by the traditional credit/degree structure of higher education.

A study by the American College Testing Program (1982) shows that credit given in colleges and universities for prior learning experience has grown steadily from 1973–74 to 1980–82. In 1980–82, 1¼ million quarter credit hours were awarded for prior learning experience. That learning is a lifelong process is increasingly being recognized by the traditional credit/degree structure of higher education.

People do learn from their experience, and the results of that learning can be reliably assessed and certified for college credit. At the same time, programs of sponsored experiential learning are on the increase in higher education. Internships, field placements, work/study assignments, structured exercises and role plays, gaming simulations, and other forms of experience-based education are playing a larger role in the curricula of undergraduate and professional programs. For many so-called nontraditional students—minorities, the poor, and mature adults—experiential learning has become the method of choice for learning and personal development. Experience-based education has become widely accepted as a method of instruction in colleges and universities across the nation.

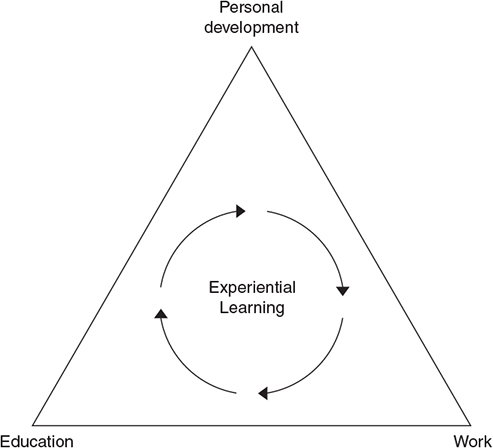

Yet in spite of its increasingly widespread use and acceptance, experiential learning has its critics and skeptics. Some see it as gimmicky and faddish, more concerned with technique and process than content and substance. It often appears too thoroughly pragmatic for the academic mind, dangerously associated with the disturbing anti-intellectual and vocationalist trends in American society. This book is in one sense addressed to the concerns of these critics and skeptics, for without guiding theory and principles, experiential learning can well become another educational fad—just new techniques for the educator’s bag of tricks. Experiential learning theory offers something more substantial and enduring. It offers the foundation for an approach to education and learning as a lifelong process that is soundly based in intellectual traditions of social psychology, philosophy, and cognitive psychology. The experiential learning model pursues a framework for examining and strengthening the critical linkages among education, work, and personal development. See Figure 1.1. It offers a system of competencies for describing job demands and corresponding educational objectives, and it emphasizes the critical linkages that can be developed between the classroom and the “real world” with experiential learning methods. It pictures the workplace as a learning environment that can enhance and supplement formal education and can foster personal development through meaningful work and career-development opportunities. And it stresses the role of formal education in lifelong learning and the development of individuals to their full potential as citizens, family members, and human beings.

Figure 1.1 Experiential Learning as the Process that Links Education, Work, and Personal Development

In this chapter, we will examine the major traditions of experiential learning, exploring the dimensions of current practice and their intellectual origins. By understanding and articulating the themes of these traditions, we will be far more capable of shaping and guiding the development of the exciting new educational programs based on experiential learning. As Kurt Lewin, one of the founders of experiential learning, said in his most famous remark, “There is nothing so practical as a good theory.”

Experiential Learning in Higher Education: The Legacy of John Dewey

In the field of higher education, there is a growing group of educators—faculty, administrators, and interested outsiders—who see experiential education as a way to revitalize the university curriculum and to cope with many of the changes facing higher education today. Although this movement is attributed to the educational philosophy of John Dewey, its source is in reality a diverse group spanning several generations. At a conference of the National Society for Internships and Experiential Education (NSIEE), a speaker remarked that there were three identifiable generations in the room: the older generation of Deweyite progressive educators, the now middle-aged children of the 1960s’ Peace Corps and civil-rights movement, and Vietnam political activists of the 1970s. Yet it is the work of Dewey, without doubt the most influential educational theorist of the twentieth century, that best articulates the guiding principles for programs of experiential learning in higher education. In 1938, Dewey wrote Experience and Education in an attempt to bring some understanding to the growing conflict between “traditional” education and his “progressive” approach. In it, he outlined the directions for change implied in his approach:

If one attempts to formulate the philosophy of education implicit in the practices of the new education, we may, I think, discover certain common principles. . . To imposition from above is opposed expression and cultivation of individuality; to external discipline is opposed free activity; to learning from texts and teachers, learning through experience; to acquisition of isolated skills and techniques by drill is opposed acquisition of them as means of attaining ends which make direct vital appeal; to preparation for a more or less remote future is opposed making the most of the opportunities of present life; to static aims and materials is opposed acquaintance with a changing world. . . .

I take it that the fundamental unity of the newer philosophy is found in the idea that there is an intimate and necessary relation between the processes of actual experience and education. [Dewey, 1938, pp. 19, 20]

In the last 40 years, many of Dewey’s ideas have found their way into “traditional” educational programs, but the challenges his approaches were developed to meet, those of coping with change and lifelong learning, have increased even more dramatically. It is to meeting these challenges that experiential educators in higher education have addressed themselves—not in the polarized spirit of what Arthur Chickering (1977) calls “either/orneriness,” but in a spirit of cooperative innovation that integrates the best of the traditional and the experiential. The tools for this work involve many traditional methods that are as old as, or in some cases older than, the formal education system itself. These methods include apprenticeships, internships, work/study programs, cooperative education, studio arts, laboratory studies, and field projects. In all these methods, learning is experiential, in the sense that:

. . . the learner is directly in touch with the realities being studied. . . . It involves direct encounter with the phenomenon being studied rather than merely thinking about the encounter or only considering the possibility of doing something with it. [Keeton and Tate, 1978, p. 2]

In higher education today, these “traditional” experiential learning methods are receiving renewed interest and attention, owing in large measure to the changing educational environment in this country. As universities have moved through open-enrollment programs and so on, to expand educational opportunities for the poor and minorities, there has been a corresponding need for educational methods that can translate the abstract ideas of academia into the concrete practical realities of these people’s lives. Many of these new students have not been rigorously socialized into the classroom/textbook way of learning but have developed their own distinctive approach to learning, sometimes characterized as “survival skills” or “street wisdom.” For these, the field placement or work/study program is an empowering experience that allows them to capitalize on their practical strengths while testing the application of ideas discussed in the classroom.

Similarly, as the population in general grows older and the frequency of adult career change continues to increase, the “action” in higher education will be centered around adult learners who demand that the relevance and application of ideas be demonstrated and tested against their own accumulated experience and wisdom. Many now approach education and midlife with a sense of fear (“I’ve forgotten how to study”) and resentment based on unpleasant memories of their childhood schooling. As Rita Weathersby has pointed out, “adults’ learning interests are embedded in their personal histories, in their visions of who they are in the world and in what they can do and want to do” (1978, p. 19). For these adults, learning methods that combine work and study, theory and practice provide a more familiar and therefore more productive arena for learning.

Finally, there is a marked trend toward vocationalism in higher education, spurred on by a group of often angry and hostile critics—students who feel cheated because the career expectations created in college have not been met, and employers who feel that the graduates they recruit into their organizations are woefully unprepared. Something has clearly gone awry in the supposed link between education and work, resulting in strong demands that higher education “shape up” and make itself relevant. There are in my view dangerous currents of anti-intellectualism in this movement, based on reactionary and counterproductive views of learning and development; but a real problem has been identified here. Experiential learning offers some avenues for solving it constructively.

For another group of educators, experiential learning is not a set of educational methods; it is a statement of fact: People do learn from their experiences. The emphasis of this group is on assessment of prior experience-based learning in order to grant academic credit for degree programs or certification for licensing in trades and professions. The granting of credit for prior experience is viewed by some as a movement of great promise:

The great significance of systematic recognition of prior learning is the linkage it provides between formal education and adult life; that is, a mechanism for integrating education and work, for recognizing the validity of all learning that is relevant to a college degree and for actively fostering recurrent education. [Willingham et al., 1977, p. 60]

Yet it has also raised great concern, primarily about the maintenance of quality, since such assessment procedures might easily be abused by “degree mills” or mail-order diploma operations. To respond to both these opportunities and these concerns, in 1973 the Cooperative Assessment of Experiential Learning (CAEL) project was established in cooperation with the Educational Testing Service to create and implement practical and valid methodologies for assessing what people have learned from their prior work and life experience.1

1. CAEL has since changed its name to the Council for the Advancement of Experiential Learning to reflect its broader interests in experiential learning methods as well as assessment.

As might be expected, researchers and practitioners in this area are more concerned with what people learn—the identifiable knowledge and skill outcomes of learning from accumulated experience—than they are with how learning takes place, the process of experiential learning. This emphasis on the outcomes of learning and their reliable assessment is critical to the establishment of effective links between education and work, since this linkage depends on the accurate identification and matching of personal skills with job demands. Since the Supreme Court’s Griggs v. Duke Power decision, establishing an equitable and valid matching process has become a top priority in our nation’s efforts toward equal employment opportunity. In that case, Griggs, an applicant for a janitorial job, sued to challenge a requirement that applicants have a high school diploma. In supporting Griggs, the court ruled that no test, certificate, or other procedure can be used to limit access to a job unless it is shown to be a valid predictor of performance on that job. This ruling, which has since been extended and supported by other high-court rulings, has set forth a great challenge to educators, behavioral scientists, and employers—to develop competence-based methods of instruction and assessment that are meaningfully related to the world of work.

Taken together, the renewed emphasis on “traditional” experiential learning methods and the emphasis on competence-based methods of education, assessment, and certification signal significant changes in the structure of higher education. Arthur Chickering sees it this way:

. . . there is no question that issues raised by experiential learning go to the heart of the academic enterprise. Experiential learning leads us to question the assumptions and conventions underlying many of our practices. It turns us away from credit hours and calendar time toward competence, working knowledge, and information pertinent to jobs, family relationships, community responsibilities, and broad social concerns. It reminds us that higher education can do more than develop verbal skills and deposit information in those storage banks between the ears. It can contribute to more complex kinds of intellectual development and to more pervasive dimensions of human development required for effective citizenship. It can help students cope with shifting developmental tasks imposed by the life cycle and rapid social change.

If these potentials are to be realized, major changes in the current structures, processes, and content of higher education will be required. The campus will no longer be the sole location for learning, the professor no longer the sole source of wisdom. Instead, campus facilities and professional expertise will be resources linked to a wide range of educational settings, to practitioners, field supervisors, and adjunct faculty. This linking together will be achieved through systematic relationships with cultural organizations, businesses, social agencies, museums, and political and governmental operations. We no longer will bind ourselves completely to the procrustean beds of fixed time units set by semester, trimester, or quarter systems, which stretch some learning to the point of transparency and lop off other learning at the head or foot. Instead, such systems will be supplemented by flexible scheduling options that tailor time to the requirements for learning and to the working realities of various experiential opportunities. Educational standards and credentials will increasingly rest on demonstrated levels of knowledge and competence as well as on actual gains made by students and the value added by college programs. We will recognize the key significance of differences among students, not only in verbal skills and academic preparation but also in learning styles, capacity for independent work, self-understanding, social awareness and human values. Batch processing of large groups will be supplemented by personalized instruction and contract learning.

The academy and the professoriat will continue to carry major responsibility for research activities, for generating new knowledge, and for supplying the perspectives necessary to cope with the major social problems rushing toward us. That work will be enriched and strengthened by more broad-based faculty and student participation and by its wide-ranging links to ongoing experiential settings. [Chickering, 1977, pp. 86–87]

Experiential Learning in Training and Organization Development: The Contributions of Kurt Lewin

Another tradition of experiential learning, larger in numbers of participants and perhaps wider in its scope of influence, stems from the research on group dynamics by the founder of American social psychology, Kurt Lewin. Lewin’s work has had a profound influence on the discipline of social psychology and on its practical counterpart, the field of organizational behavior. His innovative research methods and theories, coupled with the personal charisma of his intellectual leadership, have been felt through three generations of scholars and practitioners in both fields. Although the scope of his work has been vast, ranging from leadership and management style to mathematical contributions to social-science field theory, it is his work on group dynamics and the methodology of action research that have had the most far-reaching practical significance. From these studies came the laboratory-training method and T-groups (T = training), one of the most potent educational innovations in this century. The action-research method has proved a useful approach to planned-change interventions in small groups and large complex organizations and community systems. Today this methodology forms the cornerstone of most organization development efforts. The consistent theme in all Lewin’s work was his concern for the integration of theory and practice, stimulated if not created by his experience as a refugee to the United States from Nazi Germany. His classic studies on authoritarian, democratic, and laissez faire leadership styles were his attempt to understand in a practical way the psychological dynamics of dictatorship and democracy. His best-known quotation, “There is nothing so practical as a good theory,” symbolizes his commitment to the integration of scientific inquiry and social problem solving. His approach is illustrated no better than in the actual historical event that spawned the “discovery” of the T-group (see Marrow, 1969). In the summer of 1946, Lewin and his colleagues, most notably Ronnald Lippitt, Leland Bradford, and Kenneth Benne, set out to design a new approach to leadership and group-dynamics training for the Connecticut State Interracial Commission. The two-week training program began with an experimental emphasis encouraging group discussion and decision making in an atmosphere where staff and participants treated one another as peers. In addition, the research and training staff collected extensive observations and recordings of the groups’ activities. When the participants went home at night, the research staff gathered together to report and analyze the data collected during the day. Most of the staff felt that trainees should not be involved in these analytical sessions where their experiences and behavior were being discussed, for fear that the discussions might be harmful to them. Lewin was receptive, however, when a small group of participants asked to join in these discussions. One of the men who was there, Ronald Lippitt, describes what happened in the discussion meeting that three trainees attended:

Sometime during the evening, an observer made some remarks about the behavior of one of the three persons who were sitting in—a woman trainee. She broke in to disagree with the observation and described it from her point of view. For a while there was quite an active dialogue between the research observer, the trainer, and the trainee about the interpretation of the event, with Kurt an active prober, obviously enjoying this different source of data that had to be coped with and integrated.

At the end of the evening the trainees asked if they could come back for the next meeting at which their behavior would be evaluated. Kurt, feeling that it had been a valuable contribution rather than an intrusion, enthusiastically agreed to their return. The next night at least half of the 50 or 60 participants were there as a result of the grapevine reporting of the activity by the three delegates.

The evening session from then on became the significant learning experience of the day, with the focus on actual behavioral events and with active dialogue about differences of interpretation and observation of the events by those who had participated in them. [Lippitt, 1949]

Thus the discovery was made that learning is best facilitated in an environment where there is dialectic tension and conflict between immediate, concrete experience and analytic detachment. By bringing together the immediate experiences of the trainees and the conceptual models of the staff in an open atmosphere where inputs from each perspective could challenge and stimulate the other, a learning environment occurred with remarkable vitality and creativity.

Although Lewin was to die in 1947, the power of the educational process he had discovered was not lost on the other staff who were there. In the summer of 1947, they continued development of the insights they had gained in a three-week program for change agents, this time in Bethel, Maine. It was here that the basic outlines of T-group theory and the laboratory method began to take shape. It is important to note that even in these early beginnings, the struggle between the “here-and-now” experiential orientation and the “there-and-then” theoretical orientation that has continued to plague the movement was in evidence:

There resulted a competition between discussing here-and-now happenings, which of necessity focused on the personal, interpersonal and group levels; and discussing outside case materials. This sometimes resulted in the rejection of any serious consideration of the observer’s report of behavioral data. More often it led eventually to rejection of outside problems as less involving and fascinating. [Benne, 1964, p. 86]

Later, in the early years of the National Training Laboratories,2 this conflict expressed itself in intense debates among staff as to how conceptual material should be integrated into the “basic encounter” process of the T-group. And still later, in the 1960s, on the waves of youth culture, acid rock, and Eastern mysticism, the movement was to be virtually split apart into “West Coast” existential factions and “East Coast” traditionalists (Argyris, 1970). As we shall see later in our inquiry, this conflict between experience and theory is not unique to the laboratory-training process but is, in fact, a central dynamic in the process of experiential learning itself.

2. Now known as the NTL Institute for Applied Behavioral Sciences.

In its continuing struggle, debate, and innovation around this and other issues, the laboratory-training movement has had a profound influence on the practice of adult education, training, and organization development. In particular, it was the spawning ground for two streams of development that are of central importance to experiential learning, one of values and one of technology. T-groups and the so-called laboratory method on which they were based gave central focus to the value of subjective personal experience in learning, an emphasis that at the time stood in sharp contrast to the “empty-organism” behaviorist theories of learning and classical physical-science definitions of knowledge acquisition as an impersonal, totally logical process based on detached, objective observation. This emphasis on subjective experience has developed into a strong commitment in the practice of experiential learning to existential values of personal involvement, and responsibility and humanistic values emphasizing that feelings as well as thoughts are facts.

To the leaders of the movement, these values, coupled with the basic values of a humanistic scientific process—a spirit of inquiry, expanded consciousness and choice, and authenticity in relationships—offered new hope-filled ideals for the conduct of human relationships and the management of organizations (Schein and Bennis, 1965). More than any other single source, it was this set of core values that stimulated the modern participative-management philosophies (variously called Theory Y management, 9.9 management, System 4 management, Theory Z, and so on) so widely practiced in this country and increasingly around the world. In addition, these values have formed the guiding principles for the field of organization development and the practice of planned change in organizations, groups, and communities. The most recent and comprehensive statement of the relationship between laboratory-training values and experiential learning is the work of Argyris and Schon (1974, 1978). They maintain that learning from experience is essential for individual and organizational effectiveness and that this learning can occur only in situations where personal values and organizational norms support action based on valid information, free and informed choice, and internal commitment.

Equally important, there has emerged from the early work in sensitivity training a rapidly expanding applied technology for experiential learning. Beginning with small tasks (such as a decision-making problem) that were used in T-groups to focus the group’s experience on a particular issue (for example, processes of group decision making), there has developed an immense variety of tasks, structured exercises, simulations, cases, games, observation tools, role plays, skill-practice routines, and so on. The common core of these technologies is a simulated situation designed to create personal experiences for learners that serve to initiate their own process of inquiry and understanding. These technologies have had a profound effect on education, particularly for adult learners. The training and development field has experienced a virtual revolution in its methodology, moving from a “dog and pony show” approach that was only a fancy imitation of the traditional lecture method to a complex educational technology that relies heavily on experience-based simulations and self-directed learning designs (Knowles, 1970). Indeed, there are many who share the view of Harold Hodskinson, a former director of the National Institute for Education and the current president of the NTL Institute, that these private-sector innovations in educational technology are challenging the ability of the formal educational establishment to compete in an open market. Along with the American Society for Training and Development (ASTD), specialized associations of academics and training and development practitioners have been formed to extend experiential approaches that were initially focused on the human-relationship issues emphasized in T-groups to other content areas, such as finance, marketing, and planning through the use of computer-aided instruction, video recording, structured role-play cases, and other software and hardware techniques. In addition, there are countless small and relatively large organizations specializing in the various educational technologies that have grown to support the $50 billion training and development industry in the United States. Although the laboratory-training movement has not been responsible for all these developments, it has had an undeniable influence on many of them.

Jean Piaget and the Cognitive-Development Tradition of Experiential Learning

The Dewey and Lewin traditions of experiential learning represent external challenges to the idealist or, as James (1907) terms them, rationalist philosophies that have dominated thinking about learning and education since the Middle Ages; Dewey from the philosophical perspective of pragmatism, and Lewin from the phenomenological perspective of Gestalt psychology. The third tradition of experiential learning represents more of a challenge from within the rationalist perspective, stemming as it does from the work of the French developmental psychologist and genetic epistemologist Jean Piaget. His work on child development must stand on a par with that of Freud; but whereas Freud placed his emphasis on the socioemotional processes of development, Piaget’s focus is on cognitive-development processes—on the nature of intelligence and how it develops. Throughout his work, Piaget is as much an epistemological philosopher as he is a psychologist. In fact, he sees in his studies of the development of cognitive processes in childhood the key to understanding the nature of human knowledge itself.

It was in Piaget’s first psychological studies that he came across the insight that was to make him world-famous. He began to work as a student of Alfred Binet, the creator of the first intelligence test, standardizing test items for use in IQ and aptitude tests. During this work, Piaget’s interests began to diverge sharply from the traditional testing approach. He found himself much less interested in whether the answers that children gave to test problems were correct or not than he was in the process of reasoning that children used to arrive at the answers. He began to discover age-related regularities in these reasoning processes. Children at certain ages not only gave wrong answers but also showed qualitatively different ways of arriving at them. Younger children were not “dumber” than older children; they merely thought about things in an entirely different way. In the 50 years that followed this discovery, these ideas were to be developed and explored in thousands of studies by Piaget and his co-workers.

Stated most simply, Piaget’s theory describes how intelligence is shaped by experience. Intelligence is not an innate internal characteristic of the individual but arises as a product of the interaction between the person and his or her environment. And for Piaget, action is the key. He has shown, in careful descriptive studies of children from infants to teenagers, that abstract reasoning and the power to manipulate symbols arise from the infant’s actions in exploring and coping with the immediate concrete environment. The growing child’s system of knowing changes qualitatively in successively identifiable stages, moving from an enactive stage, where knowledge is represented in concrete actions and is not separable from the experiences that spawn it, to an ikonic stage, where knowledge is represented in images that have an increasingly autonomous status from the experiences they represent, to stages of concrete and formal operations, where knowledge is represented in symbolic terms, symbols capable of being manipulated internally with complete independence from experiential reality.

In spite of its scope and the initial flurry of interest in his work in the late 1920s, Piaget’s research did not receive wide recognition in this country until the 1960s. Stemming as it did from the French rationalist tradition, Piaget’s work was not readily acceptable to the empirical tradition of American psychology, particularly since his clinical methods did not seem to meet the rigorous experimental standards that characterized the behaviorist research programs that dominated American psychology from 1920 to 1960. In addition, Piaget’s interests were more descriptive than practical. He viewed with some disdain the pragmatic orientation of American researchers and educators who sought to speed up or facilitate the development of the cognitive stages he had identified, referring to these interests in planned change and development as the “American question.”

Piaget’s ultimate recognition in America was due in no small part to the parallel work of the most prominent American cognitive psychologist, Jerome Bruner. Bruner saw in the growing knowledge of cognitive developmental processes the scientific foundations for a theory of instruction. Knowledge of cognitive developmental stages would make it possible to design curricula in any field in such a way that subject matter could be taught respectably to learners at any age or stage of cognitive development. This idea became at once a guiding objective and a great challenge to educators. A new movement in curriculum development and teaching emerged around this idea, a movement focused on the design of experience-based educational programs using the principles of cognitive-development theory. Most of these curriculum-development efforts were addressed to the subject matters of science and mathematics for elementary and secondary students, although related efforts have been made in other subject areas, such as social studies, and such experience-based curricula can be found in some freshman and sophomore college-level courses. The major task addressed by these programs was the translation of the abstract symbolic principles of science and mathematics into modes of representation that could be grasped by people at more concrete stages of cognitive development. Typically, this representation takes the form of concrete objects that can be manipulated and experimented with by the learner to discover the scientific principle involved. Many of these were modifications of Piaget’s original experiments—for example, allowing children to pour water back and forth from tall, thin beakers to short, fat ones to discover the principle of conservation.

When introduced in the proper climate, these experience-based curricula had the same exhilarating effect on the learning process as Lewin’s discovery of the T-group. Children were freed from the lockstep pace of memorizing (or ignoring) watered-down presentations of scientific and mathematical principles that in some cases actually made learning more advanced principles more difficult; for example, to spend years learning to count only in base 10 makes learning base 2, 3, and so on, much more difficult. Learning became individualized, concrete, and self-directed. Moreover, the child was learning about the process of discovering knowledge, not just the content. Children became “little scientists,” exploring, experimenting, and drawing their own conclusions. These classrooms buzzed with the excitement and energy of intrinsically motivated learning activity. These experience-based learning programs changed the educational process in two ways. First, they altered the content of curriculum, providing new ways of teaching subjects that were formerly thought to be too advanced and sophisticated for youngsters; and second, they altered the learning process, the way that students went about learning these subjects.

Even though in many quarters these innovations met an enthusiastic reception and eventual successful implementation, they also provoked strong reaction and criticism. Some of these criticisms were justified. This new way of learning required a new approach to teaching. In some cases, teachers managed the learning process well, and intrinsically motivated learning was the result. In others, the climate for learning was somehow different; students did not learn the principle of conservation by experimenting with the water jars, they just learned how to pour water back and forth. Other criticisms seem to me less valid. Some have blamed the decline on SAT scores on the new math and other self-directed curricula that made learning appear to be fun and lacking in disciplined practice of the basics. In spirit, these debates are strongly reminiscent of the controversy surrounding Dewey’s progressive-education movement and the experience/theory conflicts concerning T-groups.

The cognitive-development tradition has had a less direct but equally powerful effect on adult learning. Although Piaget’s stages of cognitive development terminated in adolescence, the idea that there are identifiable regularities in the development process has been extended into later adulthood by a number of researchers. In method and conceptual structure, these approaches owe a great deal to the Piagetian scheme. One of the first such approaches was Lawrence Kohlberg’s extension of Piaget’s early work on moral development (see Kurtines and Greif, 1974). Kohlberg began his research on schoolchildren but soon found that only the early stages of moral judgment that he had identified were actually achieved in childhood and that for many adults, the challenges of the later stages of moral judgment still lay before them. William Perry, in his outstanding book, Forms of Intellectual and Ethical Development in the College Years (1970), found similar patterns in the way Harvard students’ systems of knowledge evolved through the college years, moving from absolutist, authority-centered, right/wrong views of knowledge in early college years, through stages of extreme relativism and, in their later college years, toward higher stages of personal commitment within relativism. Perry also found that these higher stages of development were not achieved by all students during college but, for many, posed developmental challenges that extended into their later lives. Jane Loevinger (1976) has attempted to integrate these and other cognitive developmental theories (for instance, Harvey, Hunt, and Schroder, 1961) with the socioemotional developmental theories of Erikson and others (described below) under the general rubric of ego development. Her six stages of ego development—impulsive, self-protective, conformist, conscientious, autonomous, and finally, integrated—clearly identify learning and development as a lifelong process.

The effects of these new conceptions of adult development are only now beginning to be felt. With the recognition that learning and development are lifelong processes, there comes a corresponding responsibility for social institutions and organizations to conduct their affairs in such a way that adults have experiences that facilitate their personal learning and development. One application of Kohlberg’s work in moral development, for example, has been in prison reform (Hickey and Scharf, 1980), attempting in the management of prisons to build a climate that fosters development toward higher moral stages through the creation of a “just community” within the prison society. Although perhaps not as dramatic and obvious, there is a corresponding need in many public and private organizations to improve the climate for learning and development. It is not just in prisons that people feel they must adopt self-protective and conformist postures in order to survive, seeing little reward for conscientious, autonomous, and integrated behavior.

Other Contributions to Experiential Learning Theory

Dewey, Lewin, and Piaget must stand as the foremost intellectual ancestors of experiential learning theory; however, there are other, related streams of thought that will contribute substantially to this inquiry. First among these are the therapeutic psychologies, stemming chiefly from psychoanalysis and reflected most particularly in the work of Carl Jung, although also including Erik Erikson, the humanistic traditions of Carl Rogers’s client-centered therapy, Fritz Perls’s gestalt therapy, and the self-actualization psychology of Abraham Maslow.

This school of thought brings two important dimensions to experiential learning. First is the concept of adaptation, which gives a central role to affective experience. The notion that healthy adaptation requires the effective integration of cognitive and affective processes is of course central to the practice of nearly all forms of psychotherapy. The second contribution of the therapeutic psychologies is the conception of socioemotional development throughout the life cycle. The developmental schemes of Erik Erikson, Carl Rogers, and Abraham Maslow give a consistent and articulated picture of the challenges of adult development, a picture that fits well with the cognitive schemes just discussed. Taken together, these socioemotional and cognitive-development models provide a holistic framework for describing the adult development process and the learning challenges it poses. It is Jung’s theory, however, with its concept of psychological types representing different modes of adapting to the world, and his developmental theory of individuation that will be most useful for understanding learning from experience.

A second line of contribution to experiential learning theory comes from what might be called the radical educators—in particular, the work of Brazilian educator and revolutionary Paulo Freire (1973, 1974), and of Ivan Illich (1972), whose critique of Western education and plan to “deschool” society concretely applies many of Freire’s ideas to contemporary American social problems. The core of these men’s arguments is that the educational system is primarily an agency of social control, a control that is ultimately oppressive and conservative of the capitalist system of class discrimination. The means for changing this system is by instilling in the population what Freire calls “critical consciousness,” the active exploration of the personal, experiential meaning of abstract concepts through dialogue among equals. If views of education and learning are to be cast on a political spectrum, then this viewpoint must be seen as the revolutionary extension of the liberal, humanistic perspective characteristic of the Deweyite progressive educators and laboratory-training practitioners. As such, these views serve to highlight the central role of the dialectic between abstract concepts and subjective personal experience in educational/political conflicts between the right, which places priority on maintenance of the social order, and the left, which values more highly individual freedom and expression.

Two further perspectives will be central to an inquiry helping to unravel the relationships between learning and knowledge. The first is the very active area of brain research, which is attempting to identify relationships between brain functioning and consciousness. Most relevant for our purpose is that line of research that seeks to identify and describe differences in cognitive functioning associated with the left and right hemispheres of the brain (Levy, 1980). The relevance of this work for experiential learning theory lies in the fact that the modes of knowing associated with the left and right hemispheres correspond directly with the distinction between concrete experiential and abstract cognitive approaches to learning. Thus, in his review of this literature, Corballis concludes:

Such evidence may be taken as support for the idea that the left hemisphere is the more specialized for abstract or symbolic representation, in which the symbols need bear no physical resemblance to the objects they represent, while the right hemisphere maintains representations that are isomorphic with reality itself. . . . [Corballis, 1980, p. 288]

The implication here is that these two modes of knowing or grasping the world stand as equal and complementary processes. This position stands in sharp contrast to that of Piaget and other cognitive theorists, who consider concrete, experience-oriented forms of knowing as lower developmental manifestations of true knowledge, represented by abstract propositional reasoning.

A full exploration of this issue requires examination of the philosophical literature, particularly the domains of metaphysics and epistemology. Here also, the scientific rational traditions have been dominant, even though challenged since the early years of this century by the pragmatism of Dewey, James, and others, and certain scientists and mathematicians like Michael Polanyi and Albert Einstein, who in their own work came upon the limitations of rational scientific inquiry. Of special relevance is the work of the philosopher and metaphysician Stephen Pepper (1966, 1942), who developed a system of world hypotheses on which he bases a typology of knowledge systems. With this framework as a guide, we shall be able to explore the relationships between the learning process and the knowledge systems that flow from it.

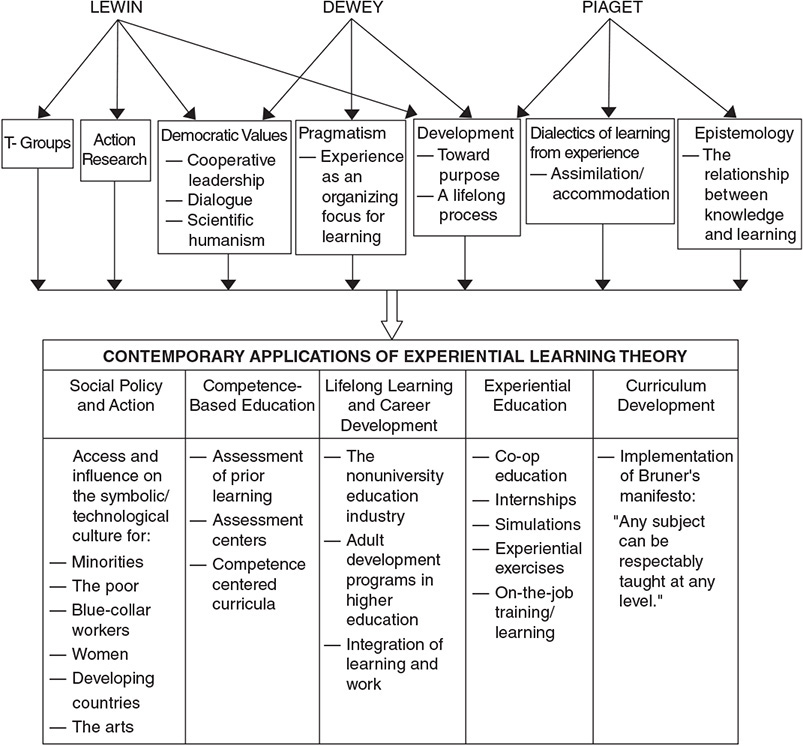

Figure 1.2 summarizes seven themes that offer guidance and direction for programs of experiential learning. These themes stem from the work of Dewey, Lewin, and Piaget. From Kurt Lewin and his followers comes the theory and technology of T-groups and action research. The articulation of the democratic values guiding experiential learning is to be found in both Lewin’s work and the educational philosophy of John Dewey. Dewey’s pragmatism forms the philosophical rationale for the primary role of personal experience in experiential learning. Common to all three traditions of experiential learning is the emphasis on development toward a life of purpose and self-direction as the organizing principle for education. Piaget’s distinctive contributions to experiential learning are his description of the learning process as a dialectic between assimilating experience into concepts and accommodating concepts to experience, and his work on epistemology—the relationship between the structure of knowledge and how it is learned.

These themes suggest guiding principles for current and emerging applications of experiential learning theory. In the case of social policy and action, experiential learning can be the basis for constructive efforts to promote access to and influence on the dominant technological/symbolic culture for those who have previously been excluded: minorities, the poor, workers, women, people in developing countries, and those in the arts. In competence-based education, experiential learning offers the theory of learning most appropriate for the assessment of prior learning and for the design of competence-centered curricula. Lifelong learning and career-development programs can find in experiential learning theory a conceptual rationale and guiding philosophy as well as practical educational tools. Finally, experiential learning suggests the principles for the conduct of experiential education in its many forms and for the design of curricula implementing Bruner’s manifesto: “Any subject can be respectably taught at any level.”

In all these applications it is important to recognize that experiential learning is not a series of techniques to be applied in current practice but a program for profoundly re-creating our personal lives and social systems. William Torbert puts the issue this way:

In seeking to organize experiential learning, we must recognize that we are stepping beyond the personally, institutionally, and epistemologically preconstituted universe and that we deeply resist this initiative, no matter how often we have returned to it. We must recognize too that the art of organizing through living inquiry—the art of continually exploring beyond pre-constituted universes and continually constructing and enacting universes in concert with others—is as yet a publicly undiscovered art. To treat the dilemma of organizing experiential learning on any lesser scale is to doom ourselves to frustration, isolation or failure. [1979, p. 42]

The Dewey, Lewin, and Piagetian traditions of experiential learning have produced a remarkable variety of vital and innovative programs. In their brief histories, these traditions have had a profound effect on education and the learning process. The influence of these ideas has been felt in formal education at all levels, in public and private organizations in this country and around the world, and in the personal lives of countless adult learners. Yet the future holds even greater challenges and opportunities. For these challenges to be successfully met, it is essential that these traditions learn from one another and cooperate to create a sound theoretical base from which to govern practice. Although in practice these traditions can appear very different—a student internship, a business simulation, a sensitivity training group, an action research project, a discovery curriculum in elementary science study—there is an underlying unity in the nature of the learning process on which they are based. It is to an examination of that process that we now turn.

Update and Reflections

Foundational Scholars of Experiential Learning Theory

nanos gigantum humeris insidentes If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.

—Isaac Newton

Chapter 1 described the conceptual foundations of experiential learning theory (ELT) with particular emphasis on the works of John Dewey, Kurt Lewin, and Jean Piaget who at the time were the particular scholars who informed my research on experiential learning and learning style. I also included other scholars—William James, Carl Rogers, Paulo Freire, Lev Vygotsky and Carl Jung—who influenced the development of other parts of the theory. I discovered Mary Parker Follett some time after the book was published and have used her work ever since. From their varied professions and cultural perspectives, these great Western scholars have had a profound impact on our thinking about learning and development, challenging and inspiring us to better ways of learning and growing as human beings. Their contributions span 100 years beginning at the end of the nineteenth century with William James, John Dewey, and Mary Parker Follett and ending at the end of the twentieth century with the deaths of Carl Rogers and Paulo Freire (refer to Figure 1.1). In spite of the Western origins of their work, their influence today is global; East and West, North and South. Their approaches were in many respects more consistent with the East Asian Confucian and Taoist spiritual traditions that were shaped by the 5,000-year-old Chinese text Yijing (![]() —the Book of Changes (Trinh and Kolb, 2011). Jung in particular was influenced in his later years by Hinduism, Buddhism, and Taoism, concluding that development toward integration and individuation is central to all religions. James also studied Eastern thought and his radical empiricism became a central focus for the Japanese philosopher Kitaro Nishida (1911).

—the Book of Changes (Trinh and Kolb, 2011). Jung in particular was influenced in his later years by Hinduism, Buddhism, and Taoism, concluding that development toward integration and individuation is central to all religions. James also studied Eastern thought and his radical empiricism became a central focus for the Japanese philosopher Kitaro Nishida (1911).

Liminal Scholars

I was first attracted to the ideas of these scholars, delighted in discovering one piece after another of the puzzle of learning from experience. Their work opened my eyes to things that had never occurred to me. Later, as I explored how they lived and did their work, I found much to be inspired by and emulate. A remarkable similarity among these nine scholars, aside from their shared view of the importance of experience in learning, is that they all are what I call liminal scholars, standing at the boundaries of the mainstream establishment of their fields and working from theoretical and methodical perspectives that ran counter to the prevailing scientific norms of their time. As a result, it is only in recent years that their ideas have reemerged to influence learning, education, and development.

Mary Parker Follett, 1868–1933, for example, was awarded a Lifetime Achievement Award by the International Leadership Association in 2011—78 years after her death. She graduated ‘summa cum laude’ from Radcliff College but was not allowed to pursue a Ph.D. because she was a woman. She was a broad thinker who spanned disciplines and schools of thought, challenging her academic colleagues to think outside their disciplinary boxes. True to her theory of relations, she refused to identify with any particular school of thought but stood in “the space between” drawing insights from both perspectives. For example, while many see her as a Gestalt theorist along with Lewin, she drew from both Gestalt theory and the opposing school of behaviorism in creating her approach. While she was a popular lecturer and writer in her day, Peter Drucker observed that “she gradually became ‘non-person’” after her death in 1933. Her radical circular theory of power that emphasized cooperation and humanistic ideas about management and organizations was foreign to the culture of management in the 1930s and 40s. Today she has gained new recognition as a foundational figure. According to Warren Bennis, “Just about everything written today about leadership and organizations comes from Mary Parker Follett’s writings and lectures” (Smith, 2002).

William James also found himself outside of the mainstream of behaviorist psychology with examination of conscious experience in his two-volume magnum opus The Principles of Psychology. He devotes the last two thirds of the work to what he called the “study of the mind from within” (James, 1890, p. 225). Today, “his ideas about consciousness have been resurrected by modern neuroscientists such as Karl Pribram and Roger Sperry who drew on James’ work for their own formulations. The geneticist Francis Crick, reviewing the philosophical implications of biological advances in our understanding of consciousness, has invoked James as a guiding philosopher who had said it all a hundred years ago” (Taylor and Wozniak, 1996, p. xxxii). His examination of the role of attention in conscious experience and his ideo-motor theory of action, addressing how consciousness of one’s learning process can be used to intentionally improve learning, were foundational for the later work on metacognition and deliberate experiential learning described in the Chapter 8 Update and Reflections. He is also recognized as the founder of the contemporary concept of dual processing theories (Evans, 2008) derived from his dual knowledge concepts of apprehension and comprehension.

Lev Vygotsky, whose prodigious brilliantly creative career was ended prematurely by his death from tuberculosis at age 38, was called the Mozart of psychology by Stephen Toulmin. This is in spite of the fact that he never had any formal training in psychology, being interested in literature, poetry, and philosophy when he was young. The Soviet authorities of his time kept him under pressure to toe the ideological Marxist line in his theories, and after his death the government repudiated his ideas. Today, however, his work is hugely influential in education around the world (Tharpe and Gallimore, 1988), and his ideas about the role of culture in the development of thought are widely cited as foundational for liberation ideologies, social constructionism, and activity theory (Bruner, 1986; Holman, Pavlica, and Thorpe, 1997).

These scholars not only studied experiential learning; they lived it. They approached their scientific inquiry as learning from experience, examining their own personal experience, using careful observation, building sophisticated and creative theoretical systems, bringing a passionate advocacy for their ideas for the betterment of humanity. I suspect they would all subscribe to Carl Rogers’ description of his approach to research, “I have come to see both research and theory as being aimed toward the inward ordering of significant experience. Thus research is not something esoteric, nor an activity in which one engages to gain professional kudos. It is the persistent, disciplined effort to make sense and order out of the phenomena of subjective experience. Such effort is justified because it is satisfying to perceive the world as having order and because rewarding results often ensue when one understands the orderly relationships which appear to exist in nature. One of these rewarding results is that the ordering of one segment of experience in a theory immediately opens up new vistas of inquiry, research, and thought, thus leading one continually forward. (I have, at times, carried on research for purposes other than the above to satisfy others, to convince opponents and sceptics, to gain prestige, and for other unsavory reasons. These errors in judgment and activity have only deepened the above positive conviction.)” (1959, p. 188).

Most, like Rogers, also chaffed at the confines of conventional disciplinary inquiry methods, “In the invitation to participate in the APA study, I have been asked to cast our theoretical thinking in the terminology of the independent-intervening-dependent variable, in so far as this is feasible. I regret that I find this terminology somehow uncongenial. I cannot justify my negative reaction very adequately, and perhaps it is an irrational one, for the logic behind these terms seems unassailable. But to me the terms seem static, they seem to deny the restless, dynamic, searching, changing aspects of scientific movement . . . The terms also seem to me to smack too much of the laboratory, where one undertakes an experiment de novo, with everything under control, rather than of a science which is endeavoring to wrest from the phenomena of experience the inherent order which they contain” (1959, p. 189).

Jean Piaget, for example, ignored sample sizes, statistical tests, and experimental and control groups in the creation of his theories. He focused instead on observations of his children, presenting them with cleverly designed puzzles and problems to understand the process of how they solved them. Unlike Binet, his mentor, and other intelligence researchers, he was less interested in correct answers than how children arrived at these answers. Not surprisingly, his successive case study technique was not well received in American psychology when it was introduced in 1926. However, by the 1950s with the rise of cognitive psychology and, particularly, Jerome Bruner’s generous advocacy for his approach, his ideas and methods gained widespread acceptance and influence in education.

Another inspiration for me was the passionate advocacy of many to the scholars for the betterment of the world through learning. The leadership provided by John Dewey and Mary Parker Follett to the Progressive Movement of the 1920s focused the profound insights of their thinking on democracy, social justice, education, and advocacy for the needy.

Paulo Freire was first a social activist where he developed his theories based on this work. His work on literacy campaigns in Brazil, later extended to other countries in South America and Africa, used what he called culture circles based on his theory of conscientiziation, the ability to problematize and take transformative action on the social, political, economic, and cultural realities that shape us. Culture circles in their process were much like Lewin’s T-groups where group participants were active participants in creating the topics to be explored through dialogue with the help of a coordinator. They differed from the T-group, however, in that their focus was on actively shaping the reality of the participants’ lives, exploring topics such as the vote for illiterates, nationalism, political revolution in Brazilian democracy, and freedom. “The first experiments with the method began in 1962 involving 300 rural farmers who were taught how to read and write in 45 days. In 1964, 20,000 culture circles were planned to be set up. However, the military coup in that year interrupted Freire’s work. He was jailed for 70 days and later went into exile in Chile” (Nyirenda, 1996, p. 4).

Kurt Lewin’s commitment to solving social problems and conflicts was born out of his marginalization growing up as a Jew in the strongly anti-Semitic culture of East Prussia. It continued throughout his life culminating in his creation of the Center for Group Dynamics at MIT and his leadership in the Commission on Community Interrelations (CCI), which conducted many action research projects, including The Connecticut State Interracial Commission to combat racial and religious prejudice that led to the creation of the T-Group (see Chapter 1, pp. 8–12). His development of the action research methodology in these projects has had a great continuing influence.

Often described as the founder of social psychology, Lewin’s influence in the field is so pervasive that it is hard to define. Warren Bennis said simply, “. . . we are all Lewinians.” John Thibaut, one of Lewin’s research assistants at MIT, said, “. . . it is not so difficult to understand why he was influential. He had an uncanny intuition about what problems were important and what kinds of concepts and research situations were necessary to study them. And though he was obsessed with theory, he was not satisfied with the attainment of theoretical closures but demanded of the theory that its implications for human life be pursued with equal patience and zeal” (cited in Marrow, 1969, p. 189). Yet, paradoxically, he too was a liminal scholar, working for the most part outside the psychological establishment. “No prestigious university offered him an appointment. (His significant work was done in odd settings, such as the Cornell School of Home Economics and the Iowa Child Welfare Research Station.) The American Psychological Association never selected him for any assignment or appointed him to any important committee. . . .” (Marrow, 1969, p. 227).

My deep admiration for Lewin stems from the many students and colleagues he nurtured and developed to become outstanding scholars in their own right. His influence in the field came not so much from his published works, which can be hard to find, but from those who worked with him. He consistently put their names forward in publications. Jerome Frank, a graduate student of Lewin’s, describes how he accomplished this, “Each new idea or problem seemed to arouse him, and he was able to share his feelings with colleagues and juniors. . . . Seminars were held in his home, and it was hard to distinguish the influence of his ideas from the influence of his personality. Because Lewin could be critical without hurting, he stimulated creativity in all those around him. . . . He seemed to enjoy all kinds of human beings and, open and free as he was, shared his ideas immediately—even if they were half-formed—eager for comments and reactions while the original idea was still being developed” (cited in Marrow, 1969, p. 54).

Contributions to Experiential Learning

The following summary of the key contributions of the foundational scholars to experiential learning can only highlight the influence of their work in experiential learning theory. Their respective approaches will be elaborated on in subsequent chapters.

William James (1841–1910)

In the introduction, I have already described how James, among the foundational scholars, is the originator of experiential learning theory in his philosophy of radical empiricism and the dual knowledge theory, knowing by apprehension (CE) and comprehension (AC) (see Chapter 3, pp. 69–77). James proposed radical empiricism as a new philosophy of reality and mind that resolved the conflicts between nineteenth century rationalism and empiricism and integrated both sensation and thought in experience. His concept of pure experience helps elucidate the dual knowledge idea of concrete experience as present-oriented experiencing free from conceptual interpretation.

James, description of the primacy of the direct perception of Concrete Experience and how it is altered by transformation through the other learning modes is the first description of the experiential learning cycle I have found: “The instant field of the present is at all times what I call ‘pure experience.’ It is only virtually or potentially either object or subject as yet. For the time being it is plain, unqualified actuality, or existence, a simple that (CE). In this naïf immediacy it is of course valid; it is there, we act upon it (AE); and the doubling of it in retrospection into a state of mind and a reality intended thereby (RO), is just one of the acts. The ‘state of mind’ first treated explicitly as such in retrospection will stand corrected or confirmed (AC), and the retrospective experience in its turn will get a similar treatment; but the immediate experience in its passing is always ‘truth,’ practical truth, something to act on, at its own moment. If the world were then and there to go out like a candle, it would remain truth absolute and objective, for it would be the ‘last word,’ would have no critic, and no one would ever oppose the thought in it to the reality intended” (1912, pp. 23–24).

John Dewey (1859–1952)

Dewey (1905) supported James in his theory of radical empiricism and pure experience against his other contemporary critics. Their ideas were foundational for the later development of the philosophy of pragmatism with C. S. Peirce.

In Art as Experience he also embraced a version of James, dual knowledge theory where self and environment are mutually transformed through a dialectic between rational controlled doing and what he called receptive undergoing, “Perception of relationship between what is done and what is undergone constitutes the work of intelligence . . . (1934, p. 45). Until the artist is satisfied in perception with what he is doing, he continues shaping and re-shaping. The making comes to an end when its result is experienced as good—and the experience comes not by mere intellectual and outside judgment but in direct perception” (1934, p. 49).

Dewey’s contribution to experiential education began in the progressive education movement he founded by establishing the laboratory schools at the University of Chicago in 1896. The following excerpts from his article “My Pedagogic Creed” (1897) describe key propositions of experiential learning:

1. “. . . education must be conceived as a continuing reconstruction of experience: . . . the process and goal of education are one and the same thing.” (13)

2. “I believe that education is a process of living and not a preparation for future living.” (7)

3. “I believe that education which does not occur through forms of life that are worth living for their own sake is always a poor substitute for genuine reality and tends to cramp and to deaden.” (7)

4. “I believe that interests are the signs and symptoms of growing power. I believe they represent dawning capacities. I believe that only through the continual and sympathetic observation of childhood’s interests can the adult enter into the child’s life and see what it is ready for.” (15)

Mary Parker Follett (1868–1933)

For Follett the keys to creativity, will, and power lie in deep experiencing. Like Dewey’s “undergoing,” surrendering the totality of one’s self to each new experience, Follett describes, “All that I am, all that life has made me, every past experience that I have had—woven into the tissue of my life—I must give to the new experience. . . . We integrate our experience, and then the richer human being that we are goes into the new experience; again we give our self and always by giving rise above the old self”(1924, pp. 136–137).

True to her Gestalt influence, she saw everything in relation. Anticipating Norbert Weiner’s discovery of cybernetics by many years, she described how we co-create one another in relationship by circular response. Through circular response transactions we create each other. In this co-creation, she describes how we can meet together in experience to evoke learning and development in one another: “. . . the essence of experience, the law of relation, is reciprocal freeing: here is the ‘rock and the substance of the human spirit.’ This is the truth of stimulus and response: evocation. We are all rooted in that great unknown in which are the infinite latents of humanity. And these latents are evoked, called forth into visibility, summoned, by the action and reaction of one on the other. All human interaction should be the evocation by each from the other of new forms undreamed of before, and all intercourse that is not evocation should be eschewed. Release, evocation—evocation by release, release by evocation—this is the fundamental law of the universe. . . . To free the energies of the human spirit is the high potentiality of all human association.” Mary Parker Follett along with Carl Rogers, Lev Vygotsky, and Paulo Freire all gave a central place to the relationship between educator and learner in their theories (see Chapter 7 Update and Reflections).

Kurt Lewin (1890–1947)

I have described Lewin’s major practical contributions to experiential learning, the T-Group laboratory method, and action research in EL Chapter 1. Lewin’s concept of the life space that describes subjective experience as a holistic field of forces is the most systematic framework for describing experience even to this day. Based on his field theory using mathematical concepts of topography, he describes the life space as the totality of the situation as the person experiences it at a moment in time. The life space is a field of interdependent forces including needs, goals, memories, as well as events in the environment, barriers, and pathways. Lewin believed that behavior was shaped by contemporary causation. Only those forces present in the here-and-now influenced behavior. The life space conception was inspirational for the experiential learning theory concept of learning spaces described in the Chapter 7 Update and Reflections.

Jean Piaget (1896–1980)

Piaget’s constructivism describes the child’s development from less to more complex discrete stages of thinking driven by the dialectic tension between previous information acquired through the process of assimilation and the accommodation of existing cognitive structures to new information. While his account portrays a linear developmental continuum with stages roughly equivalent to the child’s age (as described in Chapter 2, pp. 54–55), I modified his scheme in its incorporation into experiential learning theory to depict it within the learning cycle (see Figure 2.3) to indicate that development beyond adolescence involves the integration of abstract cognitive frameworks with experience (see Chapter 6, pp. 201–205 and Update and Reflections).

The educational implications of constructivism, that learning is best facilitated by a process that draws out the students’ beliefs and ideas about a topic so that they can be examined, tested, and integrated with new, more refined ideas, has had a profound impact on education at all levels all over the world (see Chapter 3 Update and Reflections). In addition, his stage theory has formed the foundation of nearly all theories of adult development (see Chapter 6 Update and Reflections).

Lev Vygotsky (1896–1934)

While much attention has been given to the origins of experiential learning in the constructivism of Piaget, less attention has been given to its basis in the social constructivism of Vygotsky (Kayes, 2002). Piaget focused on the process of internal cognitive development in the individual, while the focus for Vygotsky was on the historical, cultural and social context of individuals in a relationship, emphasizing the “tools of culture” and mentoring by more knowledgeable community members. He is best known for his concept of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD)—a learning space that promotes the transition from a pedagogical stage, where something can be demonstrated with the assistance of a more knowledgeable other, to an expert stage of independent performance. The ZPD is based on his law of internalization where the child’s novel capacities begin in the interpersonal realm and are gradually transferred into the intra-personal realm (Vygotsky, 1978). What is internalized is “mediational means” or tools of culture, the most important of which is language.

The key technique for accomplishing this transition is called “scaffolding.” In scaffolding the educator tailors the learning process to the individual needs and developmental level of the learner. Scaffolding provides the structure and support necessary to progressively build knowledge. The model of teaching around the cycle described above provides a framework for this scaffolding process. When an educator has a personal relationship with a learner, he or she can skillfully intervene to reinforce or alter a learner’s pattern of interaction with the world (see Chapter 7 Update and Reflections).

Carl Jung (1875–1961)