Chapter 1. Project Management Framework Fundamentals

This chapter covers the following PMP exam topics:

![]() Understand the Project Management Framework

Understand the Project Management Framework

![]() Explain Organizational and Environmental Factors

Explain Organizational and Environmental Factors

![]() Describe the Project Life Cycle

Describe the Project Life Cycle

(For more information on the PMP exam topics, see “About the PMP Exam” in the Introduction.)

This chapter introduces the basic terminology and topics that the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK) covers and provides a general outline for the PMP exam material. The Project Management Institute (PMI) was formed in 1969 as a group dedicated to the discipline of project management. PMI published the first draft of the PMBOK in 1986 as a study guide for the PMP certification exam and a standard collection of project management best practices. The current PMBOK version is the result of changes in the project management discipline, as well as standardization of project management concepts. The topics in this chapter correspond to the first three chapters of the PMBOK, including project introduction, project life cycle, and project processes.

The Project Management framework is the first section of the PMBOK and serves as the foundation for the document. Briefly stated, it presents the structure used to discuss and organize projects. The PMBOK uses this structure to document all facets of a project on which consensus has been reached among a broadly diverse group of project managers. The PMBOK is not only the document that defines the methods to manage projects; it is also the most widely accepted project management foundation. This document provides a frame of reference for managing projects and teaching the fundamental concepts of project management.

Note that the PMBOK does not address every area of project management in all industries. It does, however, address the recognized best practices for the management of a single project. Most organizations have developed their own practices that are specific to their organization.

It is important that you read the PMBOK. Although many good references and test preparation sources can help prepare for the PMP exam, they are not substitutes for the PMBOK itself.

The PMP exam tests your knowledge of project management in the context of the PMBOK and PMI philosophy. Regardless of the experience you might have in project management, your answers will be correct only if they concur with PMI philosophy. If the PMBOK presents a method that differs from your experience, go with the PMBOK’s approach. That being said, the PMP exam will also contain questions that are not specifically addressed in the PMBOK. It is important that you coordinate your understanding of project management with that of PMI. This book will help you do that.

What a Project Is and What It Is Not

The starting point in discussing how projects should be properly managed is to first understand what a project is (and what it is not). According to the PMBOK, a project has two main characteristics that differentiate it from regular, day-to-day operation. Know these two characteristics of projects.

A Project Is Temporary

Unlike day-to-day operation, a project has specific starting and ending dates. Of the two dates, the ending date is the more important. A project ends either when its objectives have been met or when the project is terminated due to its objectives not being met. If you can’t tell when an endeavor starts or ends, it’s not a project. This characteristic is important because projects are, by definition, constrained by a schedule.

A Project Is an Endeavor Undertaken to Produce a Unique Product or Service

In addition to having a discrete time frame, a project must also produce one or more specific products or services. A project must “do” something. A project that terminates on schedule might still not be successful; it must also produce something unique.

ExamAlert

The PMP exam contains a few questions on the definition of project. Simply put, if an endeavor fails to meet both of the project criteria, it is an operational activity. Remember this: Projects exist to achieve a goal. When the goal is met, the project is complete. Operations conduct activities that sustain processes, often indefinitely.

Programs, Portfolios, and the PMO

It is common practice for an organization to have more than one project active at a time. In fact, several projects that share common characteristics or are related in some way are often grouped together to make management of the projects more efficient. A group of related projects is called a program. If there are multiple projects and programs in an organization, they can further be grouped into one or more portfolios. A portfolio is a collection of projects and programs that satisfy the strategic needs of an organization.

ExamAlert

The PMP exam and the PMBOK only cover techniques to manage single projects. You need to be aware of what programs and portfolios are, but you will only address single project management topics in regard to the exam.

Many organizations have found that project management is so effective that they maintain an organizational unit with the primary responsibility of managing projects and programs. The unit is commonly called the project management office (PMO). The PMO is responsible for coordinating projects and, in some cases, providing resources for managing projects. A PMO can make the project manager’s job easier by maintaining project management standards and implementing policies and procedures that are common within the organization. According to the PMBOK, the PMO supports project managers by

![]() “Managing shared resources across all projects administered by the PMO.”

“Managing shared resources across all projects administered by the PMO.”

![]() “Identifying and developing project management methodology, best practices, and standards.”

“Identifying and developing project management methodology, best practices, and standards.”

![]() “Coaching, mentoring, training, and oversight.”

“Coaching, mentoring, training, and oversight.”

![]() “Monitoring compliance with project management standards policies, procedures, and templates via project audits.”

“Monitoring compliance with project management standards policies, procedures, and templates via project audits.”

![]() “Developing and managing project policies, procedures, templates, and other shared documentation (organizational process assets).”

“Developing and managing project policies, procedures, templates, and other shared documentation (organizational process assets).”

![]() “Coordinating communication across projects.”

“Coordinating communication across projects.”

The PMBOK defines three types of PMO structures, depending on the amount of influence and control the PMO has over projects. These are the three types of PMO structures:

![]() Supportive—The PMO supplies technical and administrative support and provides input to project managers, as needed. This type of PMO provides low control.

Supportive—The PMO supplies technical and administrative support and provides input to project managers, as needed. This type of PMO provides low control.

![]() Controlling—The PMO does not directly manage projects but does require compliance with organizational methodologies, frameworks, and tools. This type of PMO provides medium control.

Controlling—The PMO does not directly manage projects but does require compliance with organizational methodologies, frameworks, and tools. This type of PMO provides medium control.

![]() Directive—The PMO manages projects directly. This type of PMO provides a high level of control.

Directive—The PMO manages projects directly. This type of PMO provides a high level of control.

What Project Management Is

According to the PMBOK, “Project management is the application of knowledge, skills, tools, and techniques to project activities to meet project requirements.” In other words, project management is taking what you know and proactively applying that knowledge to effectively guide your project through its life cycle.

The purpose of applying this knowledge is to help the project meet its objectives. Sounds pretty straightforward, doesn’t it? The PMP exam tests your project management knowledge, but it’s more than that. It is also a test that evaluates your ability to apply your knowledge through the use of skills, tools, and techniques. The application of project management knowledge is what makes the exam challenging. Understanding project management is more than just memorization. You do have to memorize some things (and we’ll let you know what those are), but it’s more important to know how to apply what you know. Some of the hardest questions on the exam look like they have two, or even three, correct answers. You really have to understand the PMBOK to choose the most correct answer.

ExamAlert

Did you notice I said the most correct answer? The PMP exam throws several questions at you that seem to have more than one correct answer. In fact, many questions on the exam have multiple answers that can be considered correct. You need to be able to choose the one that best satisfies the question as asked. Read each question carefully and always remember that the PMBOK rules.

Changes in the PMBOK Guide, Fifth Edition

PMI is constantly reviewing its documents and exams for currency and applicability to today’s project management practices. The PMBOK Guide, Fifth Edition, was released in December 2012 as an update to the previous edition, the PMBOK Guide, Fourth Edition. There are several changes in the new edition. None of the changes are major, although the PMBOK has been slightly reorganized to better reflect current project management practices. The changes from the Fourth Edition focus on increasing the consistency and clarity of the guide and on harmonizing with other PMI standards and ISO 21500. Here is a summary of the changes that are included in the PMBOK Guide, Fifth Edition:

![]() Established business rules to promote clarity and consistency within the inputs, tools and techniques, and outputs for all processes.

Established business rules to promote clarity and consistency within the inputs, tools and techniques, and outputs for all processes.

![]() Ensured that terms in the PMBOK align with the PMI Lexicon of Project Management Terms.

Ensured that terms in the PMBOK align with the PMI Lexicon of Project Management Terms.

![]() Improved consistency by defining and using standard terms throughout the PMBOK, including work performance data, work performance information, and work performance reports.

Improved consistency by defining and using standard terms throughout the PMBOK, including work performance data, work performance information, and work performance reports.

![]() Added five new processes, moved one to a different knowledge area, and added a new knowledge area. The PMBOK Guide, Fifth Edition, defines a total of 47 processes (up from 42 defined in the PMBOK Guide, Fourth Edition).

Added five new processes, moved one to a different knowledge area, and added a new knowledge area. The PMBOK Guide, Fifth Edition, defines a total of 47 processes (up from 42 defined in the PMBOK Guide, Fourth Edition).

![]() Clarified the differences between the Project Management Plan and the Project Documents.

Clarified the differences between the Project Management Plan and the Project Documents.

![]() Moved the Standard for Project Management of a Project from Section 3 to Appendix A1 and replaced Section 3 with an overview of the process groups and knowledge areas.

Moved the Standard for Project Management of a Project from Section 3 to Appendix A1 and replaced Section 3 with an overview of the process groups and knowledge areas.

ExamAlert

PMI transitioned to the PMBOK Guide, Fifth Edition exam on July 31, 2013. All PMP exams after the transition date are based on the PMBOK Guide, Fifth Edition. If you have been studying another reference that is based on the PMBOK Guide, Fourth Edition, make sure you review the newer PMBOK before taking the exam. (Of course, this reference covers the new PMBOK material.)

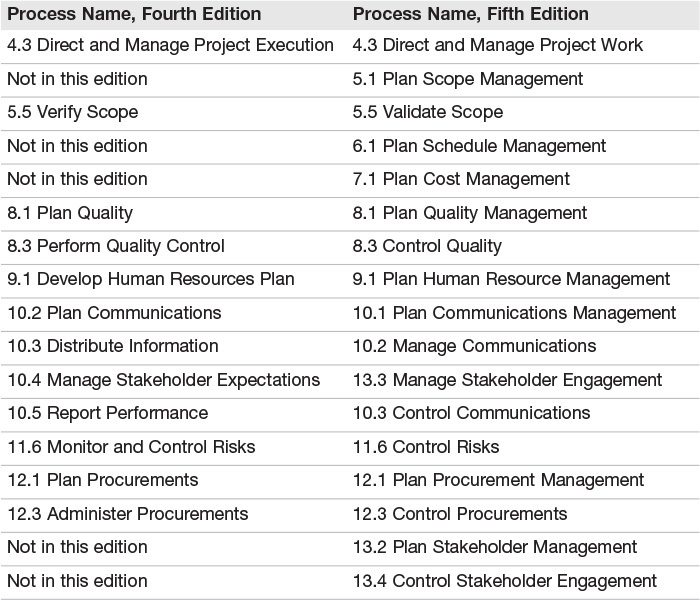

To summarize the process additions, deletions, and name changes, Table 1.1 lists the processes that have changed in the PMBOK Guide, Fifth Edition. (Some processes only change the section number where they appear in the document. We highlight just name changes here.)

In addition to the process name changes, each knowledge area incorporates changes from the PMBOK Guide, Fourth Edition, that help to clarify the document and make the various sections more cohesive. The PMBOK Guide, Fifth Edition, also separates stakeholder activities from the Project Communications Management knowledge area to create a new knowledge area, Project Stakeholder Management. Be sure you focus on the changed material as you study for the exam if you are already comfortable with a previous PMBOK edition.

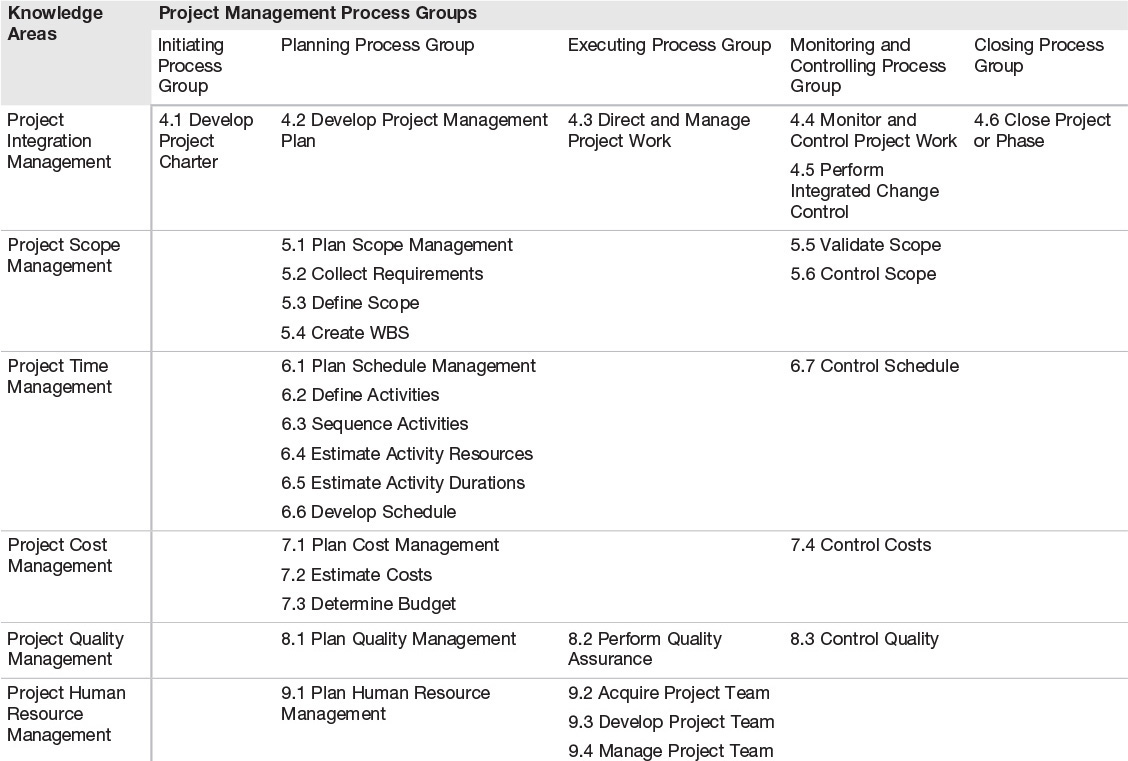

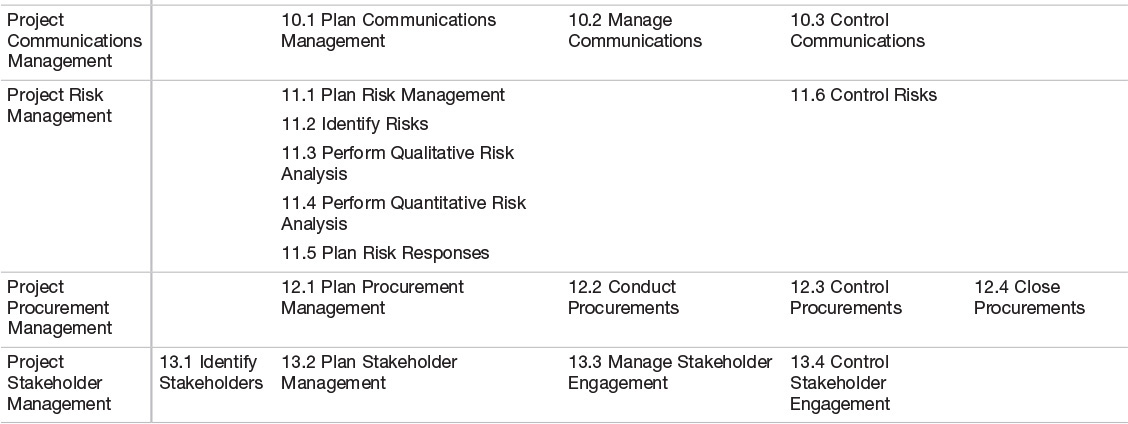

Project Management Knowledge Areas

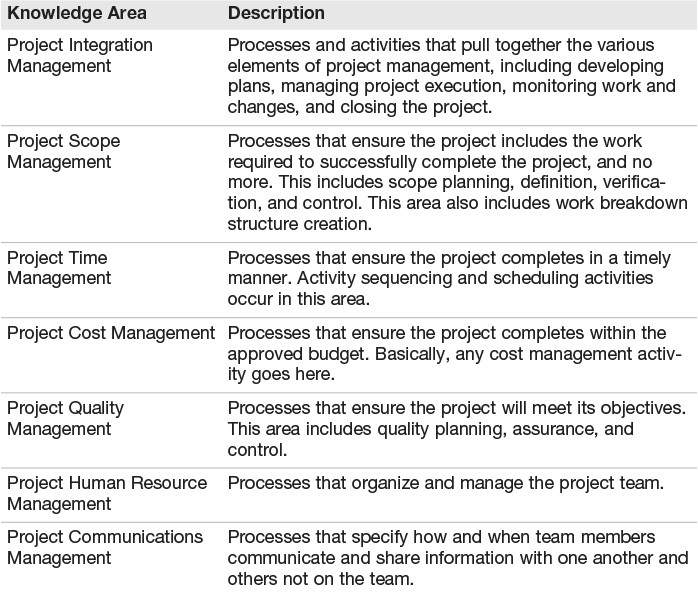

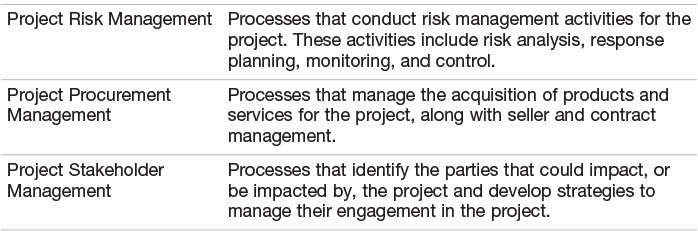

The PMBOK organizes all the activities that define a project’s life cycle into 47 processes. These processes represent content from 10 knowledge areas. It is extremely important to have a good understanding of each of the project processes and how they relate to one another. We’ll go into more details of each process in a later section. For now, understand the 10 knowledge areas and what purposes they serve for the project. The PMBOK itself is organized by knowledge areas, and there is a separate chapter for each knowledge area. Table 1.2 shows the 10 knowledge areas and gives a brief description of each.

Figure 1.1 shows each of the project management knowledge areas and the specific processes contained in each one.

In nearly all cases, a project exists within a larger organization. Some group or organization creates each project, and the project team must operate within the larger organization’s environment. Simply put, no project exists in a vacuum. Every process within every project is affected to some degree by organizational culture and practices. Let’s explore some of the most common organizational effects on projects.

Working with Organizational Politics and Influences

In many cases, the extent to which the initiating organization derives revenue from projects affects how projects are regarded. In an organization where the primary stream of revenue comes from various projects, the project manager generally enjoys more authority and access to resources. On the other hand, organizations that create projects only due to outside demands will likely make it more difficult for the project manager to acquire resources. If a particular resource is needed to perform both operational and project work, many functional managers will resist requests to assign that resource to a project.

Another factor that influences how projects operate with respect to sponsoring organizations is the level of sponsorship from the project’s origin. A project that has a sponsor who is at the director level typically encounters far less resistance than one with a sponsor who is a functional manager. The reason for this is simple: Many managers tend to protect their own resources and are not willing to share them unless they have sufficient motivation to do so. The more authority a project sponsor possesses, the easier time the project manager has when requesting resources from various sources.

In addition to the previous issues, the sponsoring organization’s maturity and project orientation can have a substantial effect on each project. More mature organizations tend to have more general management practices in place that allow projects to operate in a stable environment. Projects in less mature organizations might find that they must compete for resources and management attention due to having fewer established policies. There can also be many issues related to the culture of an organization, such as values, beliefs, and expectations that can affect projects.

The last major factor that has a material impact on how projects exist within the larger organization is the management style of the organization. The next section introduces the main types of project management organizations and their relative strengths and weaknesses.

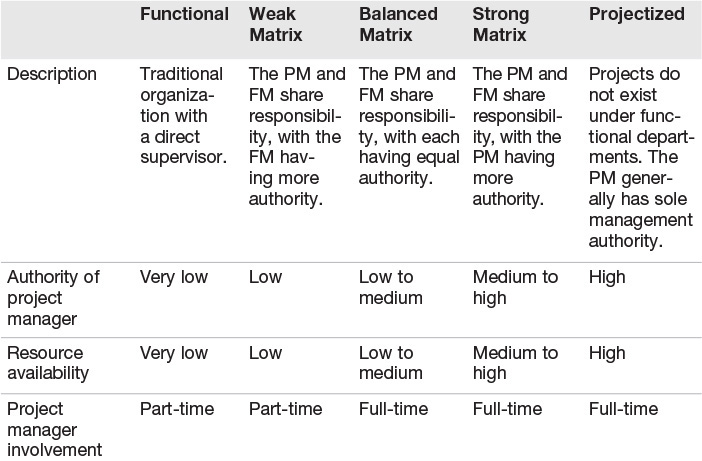

Differentiating Functional, Matrix, and Projectized Organizational Structures

Each organization approaches the relationship between operations and projects differently. The PMBOK defines three main organizational structures that affect many aspects of a project, including

![]() The project manager’s authority

The project manager’s authority

![]() Resource availability

Resource availability

![]() The project manager and administrative staff roles

The project manager and administrative staff roles

Functional Organizational Structure

A functional organizational structure is a classical hierarchy in which each employee has a single superior. Employees are then organized by specialty, and work accomplished is generally specific to that specialty. Communication with other groups generally occurs by passing information requests up the hierarchy and over to the desired group or manager. Of all the organizational structures, this one tends to be the most difficult for the project manager. The project manager lacks the authority to assign resources and must acquire people and other resources from multiple functional managers. In many cases, the project’s priority is considered to be lower than operations for which the functional manager is directly responsible. In these organizations, it is common for the project manager to appeal to the senior management to resolve resource issues.

Matrix Organizational Structure

A matrix organization is a blended organizational structure. Although a functional hierarchy is still in place, the project manager is recognized as a valuable position and is given more authority to manage the project and assign resources. Matrix organizations can be further divided into weak, balanced, and strong matrix organizations. The difference between the three is the level of authority given to the project manager (PM). A weak matrix gives more authority to the functional manager (FM), whereas the strong matrix gives more power to the PM. As the name suggests, the balanced matrix balances power between the FM and the PM.

Projectized Organizational Structure

In a projectized organization, there is no defined hierarchy. Resources are brought together specifically for the purpose of a project. The necessary resources are acquired for the project, and the people assigned to the project work for the PM only for the duration of the project. At the end of each project, resources are either reassigned to another project or returned to a resource pool.

There are many subtle differences between the types of structures. Table 1.3 compares the various organizational structures and the roles of the project manager and the functional manager.

Understanding Enterprise Environmental Factors

It is the responsibility of a project manager to understand the project environment. All projects operate within a specific environment or blend of environments. In addition to understanding the organizational structure, a project manager needs to understand the effects that enterprise environmental factors play in managing projects. The most obvious enterprise environmental factors for projects are

![]() Organizational culture and structure

Organizational culture and structure

![]() Human resources currently in place

Human resources currently in place

![]() Political climate

Political climate

![]() Government or industry standards and regulations

Government or industry standards and regulations

![]() Infrastructure

Infrastructure

![]() Marketplace conditions

Marketplace conditions

![]() Stakeholder risk tolerances

Stakeholder risk tolerances

Organizational Process Assets

Two of the goals of project management are to make projects repeatable and to do a better job with each new project. To this end, organizations that are committed to effective project management develop shared, and often standardized, resources to help project managers do their jobs well. These resources are called organizational process assets and include formal and informal plans, policies, procedures, and guidelines.

These assets might begin as a simple set of templates and project-related documents. As these assets are put to use, they tend to be altered and refined. New documents often become necessary or useful as well. All lessons learned from previous projects should be examined to apply any necessary changes to the process assets. This continuous process of improvement encourages the base of assets to become a critical core of resources for any project. You will see organizational process assets mentioned in many of the project management processes. The assets can include many types of documents, including

![]() Organizational policies

Organizational policies

![]() Operational guidelines

Operational guidelines

![]() Templates used to create many project process outputs

Templates used to create many project process outputs

![]() Project closure procedures

Project closure procedures

![]() Communication requirements and procedures

Communication requirements and procedures

![]() Change control procedures

Change control procedures

![]() Financial control procedures

Financial control procedures

![]() Quality control procedures

Quality control procedures

![]() Project historical files

Project historical files

![]() Pertinent organizational knowledge bases

Pertinent organizational knowledge bases

You will see “Organizational Process Assets” as inputs for many project management processes. Remember that this simply refers to any organization’s central repository of plans, policies, procedures, and guidelines that a project manager can use as a starting point when creating process outputs.

Projects occur in the context of an organization that is larger than the project itself. It is important to understand the structure of a project and how it matures from beginning to end to properly manage the work of the project. This section examines the life cycle of projects and how they are organized to be effective and repeatable.

Understanding Project Life Cycles

The project manager and project team have one shared goal: to carry out the work of the project for the purpose of meeting the project’s objectives. Every project has an inception, a period during which activities move the project toward completion, and a termination (either successful or unsuccessful). Taken together, these phases represent the path a project takes from the beginning to its end and are generally referred to as the project life cycle.

The project life cycle is often formally divided into phases that describe common activities as the project matures. The activities near the beginning of a project look different from activities closer to the end of the project. Most projects share activity characteristics as the project moves through its life cycle. You might see several questions on the exam that ask you to compare different phases in a project’s life cycle. In general, here are the common comparisons of early and late project life cycle activities:

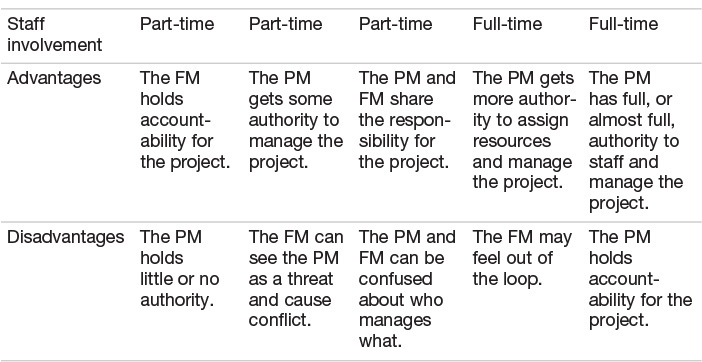

![]() The least is known about the project near its beginning—As the project matures, more is learned about the project and the product it produces. This process is called progressive elaboration. As you learn more about the project, all plans and projections become more accurate.

The least is known about the project near its beginning—As the project matures, more is learned about the project and the product it produces. This process is called progressive elaboration. As you learn more about the project, all plans and projections become more accurate.

![]() The level of uncertainty and risk is the highest at the beginning of a project—As more is learned about the project and more of the project’s work is completed, uncertainty and risk decrease.

The level of uncertainty and risk is the highest at the beginning of a project—As more is learned about the project and more of the project’s work is completed, uncertainty and risk decrease.

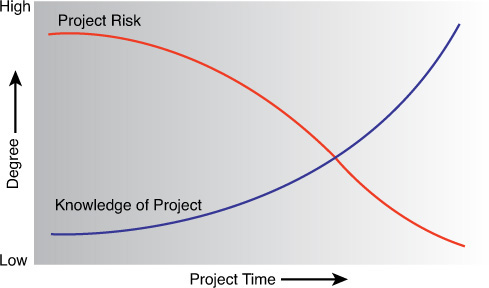

![]() Stakeholders assert the greatest influence on the outcome of a project at the beginning—After the project starts, the stakeholders’ influence continually declines. Their influence to affect the project’s outcome is at its lowest point at the end of the project.

Stakeholders assert the greatest influence on the outcome of a project at the beginning—After the project starts, the stakeholders’ influence continually declines. Their influence to affect the project’s outcome is at its lowest point at the end of the project.

![]() Costs and personnel activity vary throughout a project—Costs and personnel activity are both low at the beginning of a project, are high near the middle of the project, and tend to taper off to a low level as the project nears completion.

Costs and personnel activity vary throughout a project—Costs and personnel activity are both low at the beginning of a project, are high near the middle of the project, and tend to taper off to a low level as the project nears completion.

![]() The cost associated with project changes is at its lowest point at the project’s beginning—No work has been done, so changing is easy. As more and more work is completed, the cost of any changes rises.

The cost associated with project changes is at its lowest point at the project’s beginning—No work has been done, so changing is easy. As more and more work is completed, the cost of any changes rises.

One of the most important relationships to understand throughout the project life cycle is the relationship between project knowledge and risk. As stated earlier, knowledge of a project increases as more work is done due to progressive elaboration, and risk decreases as the project moves toward completion. Figure 1.2 depicts the relationship between knowledge and risk.

Another important relationship present in a project’s life cycle is the relationship between the declining influence of stakeholders on the outcome of a project and the cost of changes and error corrections. Because little or no work has been accomplished near the beginning of a project, changes require few adjustments and are generally low in cost. At the same time, stakeholders can assert their authority and make changes to the project’s direction. As more work is accomplished, the impact and cost of changes increase and leave stakeholders with fewer and fewer viable options to affect the project’s product. Figure 1.3 shows how the influences of stakeholders and cost of changes are related to the project life cycle.

Although all projects are unique, they do share common components or processes that are normally grouped together. Here are the generally accepted process groups defined in the PMBOK:

![]() Initiating

Initiating

![]() Planning

Planning

![]() Executing

Executing

![]() Controlling

Controlling

![]() Closing

Closing

Moving from one phase in the life cycle to another is generally accompanied by a transfer of technical material or control from one group to another. Most phases officially end when the work from one phase is accepted as sufficient to meet that phase’s objectives and is passed onto the next phase. The work from one phase could be documentation, plans, components necessary for a subsequent phase, or any work product that contributes to the project’s objectives.

Who Are the Stakeholders?

A project exists to satisfy a need. (Remember that a project produces a unique product or service.) Without a need of some sort, a project is not necessary. Needs originate with one or more people; someone has to state a need. As a result, a project fills the need and likely affects some people or organizations. All people and organizations that have an interest in the project or its outcome are called project stakeholders. The stakeholders provide input to the requirements of the project and the direction the project should take throughout its life cycle.

The list of stakeholders can be large and can change as the project matures. One of the first requirements to properly manage a project is the creation of a key stakeholder list. Be very careful to include all key stakeholders. Many projects have been derailed due to the political fallout of excluding a key stakeholder. Every potential stakeholder cannot be included in all aspects of a project, so it is important to identify the stakeholders who represent all other stakeholders.

Although it sounds easy to create a list of stakeholders, in reality they are not always easy to identify. You often need to ask many questions of many people to ensure that you create a complete stakeholder list. Because stakeholders provide input for the project requirements and mold the image of the project and its expectations, it is vitally important that you be as persistent as necessary to identify all potential stakeholders. Key stakeholders can include

![]() Project manager—The person responsible for managing the project.

Project manager—The person responsible for managing the project.

![]() Customer or user—The person or organization that will receive and use the project’s product or service.

Customer or user—The person or organization that will receive and use the project’s product or service.

![]() Performing organization—The organization that performs the work of the project.

Performing organization—The organization that performs the work of the project.

![]() Project team members—The members of the team who are directly involved in performing the work of the project.

Project team members—The members of the team who are directly involved in performing the work of the project.

![]() Project management team—Project team members who are directly involved in managing the project.

Project management team—Project team members who are directly involved in managing the project.

![]() Sponsor—The person or organization that provides the authority and financial resources for the project.

Sponsor—The person or organization that provides the authority and financial resources for the project.

![]() Influencers—People or groups not directly related to the project’s product but with the ability to affect the project in a positive or negative way.

Influencers—People or groups not directly related to the project’s product but with the ability to affect the project in a positive or negative way.

![]() Project management office (PMO)—If a PMO exists, it can be a stakeholder if it has responsibility for the project’s outcome.

Project management office (PMO)—If a PMO exists, it can be a stakeholder if it has responsibility for the project’s outcome.

The Project Manager

One of the most visible stakeholders is the project manager, the person responsible for managing the project and a key stakeholder. Although the project manager is the most visible stakeholder, he or she does not have the ultimate authority or responsibility for any project. Senior management—specifically the project sponsor—has the ultimate authority over the project. Senior management issues the project charter (discussed in Chapter 3, “Understand Project Initiating”) and is responsible for the project. Senior management grants the project manager the authority to get the job done and to resolve many issues. The project manager is also in charge of the project but often does not control the resources.

Look at these sections and chapters in the PMBOK Guide, Fifth Edition, for more detailed information on the project manager’s roles and responsibilities:

![]() “Introduction,” Chapter 1

“Introduction,” Chapter 1

![]() “Organizational Influences on Project Management,” Chapter 2

“Organizational Influences on Project Management,” Chapter 2

![]() “Project Human Resource Management,” Chapter 9

“Project Human Resource Management,” Chapter 9

![]() “Project Stakeholder Management,” Chapter 13

“Project Stakeholder Management,” Chapter 13

![]() “Interpersonal Skills,” Appendix X3

“Interpersonal Skills,” Appendix X3

ExamAlert

You must have a clear understanding of the project manager’s roles and responsibilities for this exam. Go through the PMBOK, search for “project manager,” and look at all the responsibilities defined. Know what a project manager must do, should do, and should not do.

The PDF version of the PMBOK enables you to easily search for terms. Use it to search for any terms you are unsure of.

Managing Project Constraints

Managing projects is a continual process of balancing the various competing project variables, or constraints. Historically, project managers have focused on the three common constraints of scope, time, and cost. But in reality, there are more than just three constraints. Each of the project constraints is related and has an effect on the outcome of a project. The project manager must manage the competing constraints to successfully complete a project. Too much attention on one generally means one or more of the others suffer. A major concern of a project manager is to ensure that each of these variables is balanced with the others at all times. The project constraints include, but are not limited to,

![]() Scope—The amount of work to be done. Increasing the scope causes more work to be done and vice versa.

Scope—The amount of work to be done. Increasing the scope causes more work to be done and vice versa.

![]() Quality—The quality standards that the project must fulfill. Higher quality standards often require more work, impacting other constraints.

Quality—The quality standards that the project must fulfill. Higher quality standards often require more work, impacting other constraints.

![]() Schedule—The time required to complete the project. Modifying the schedule alters the start and end dates for tasks in the project and can alter the project’s overall end date.

Schedule—The time required to complete the project. Modifying the schedule alters the start and end dates for tasks in the project and can alter the project’s overall end date.

![]() Budget—The cost required to accomplish the project’s objectives. Modifying the cost of the project generally has an impact on the scope, time, or quality of the project.

Budget—The cost required to accomplish the project’s objectives. Modifying the cost of the project generally has an impact on the scope, time, or quality of the project.

![]() Resources—Resources that are available to conduct the work of the project.

Resources—Resources that are available to conduct the work of the project.

![]() Risk—The trade-off that comes with each decision made in the planning and execution of a project. Riskier decisions might have consequences that affect other constraints.

Risk—The trade-off that comes with each decision made in the planning and execution of a project. Riskier decisions might have consequences that affect other constraints.

Any change to one of the variables has some effect on one or several of the remaining variables. Likewise, a change to any of the variables has an impact on the overall outcome of the project. The key to understanding the project constraints is that they are all interrelated. For example, if you decrease the cost of your project, it is likely that you decrease the quality and perhaps even increase the risk. With less money, less work gets done. Or you might find that it takes more time to produce the same result with less money. Either way, a change to cost affects other variables.

Even though this concept is fairly straightforward, a project manager must stay on top of each variable to ensure that they are all balanced. In addition to managing the project constraints, the project manager also is responsible for explaining the need for balance to the stakeholders. All too often, stakeholders favor one constraint over another. You have to ensure that the stakeholders understand the need for balancing all constraints.

Project Management Process Groups

As we discussed earlier in this chapter, work executed during a project can be expressed in specific groups of processes. Each project moves through each of the groups of processes, some more than once. These common collections of processes that the PMBOK defines are called process groups. Process groups serve to group processes in a project that represent related tasks and mark a project’s migration toward completion.

Remember that the PMBOK defines these five process groups:

![]() Initiating—Defines the project objectives and grants authority to the project manager.

Initiating—Defines the project objectives and grants authority to the project manager.

![]() Planning—Refines the project objectives and scope and plans the steps necessary to meet the project’s objectives.

Planning—Refines the project objectives and scope and plans the steps necessary to meet the project’s objectives.

![]() Executing—Puts the project plan into motion and performs the work of the project.

Executing—Puts the project plan into motion and performs the work of the project.

![]() Monitoring and Controlling—Measures the performance of the executing activities and compares the results with the project plan.

Monitoring and Controlling—Measures the performance of the executing activities and compares the results with the project plan.

![]() Closing—Documents the formal acceptance of the project’s product and brings all aspects of the project to a close.

Closing—Documents the formal acceptance of the project’s product and brings all aspects of the project to a close.

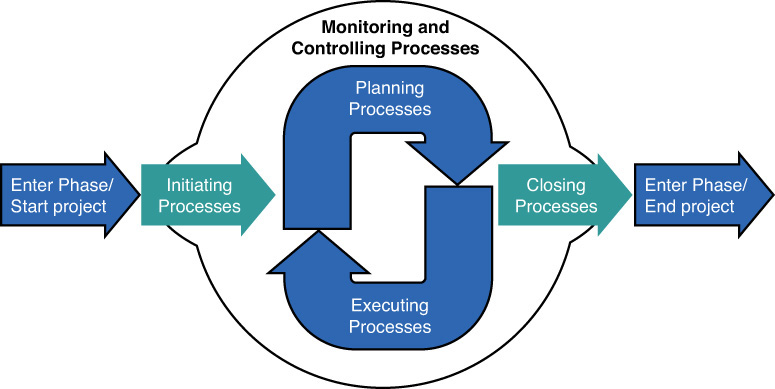

Figure 1.4 depicts how the five process groups provide a framework for the project.

All the process groups are discussed in detail throughout the rest of this book. Be sure you are comfortable with how a project flows from inception through each of the process groups. The PMBOK Guide, Fifth Edition, has added new figures that depict process flows, inputs and outputs, and interaction between process groups. Look at the PMBOK Guide, Fifth Edition, Chapter 3 for these figures. Use them: They will help you remember how the processes flow throughout the project.

Understanding Project Life Cycle and Project Management Processes Relationships

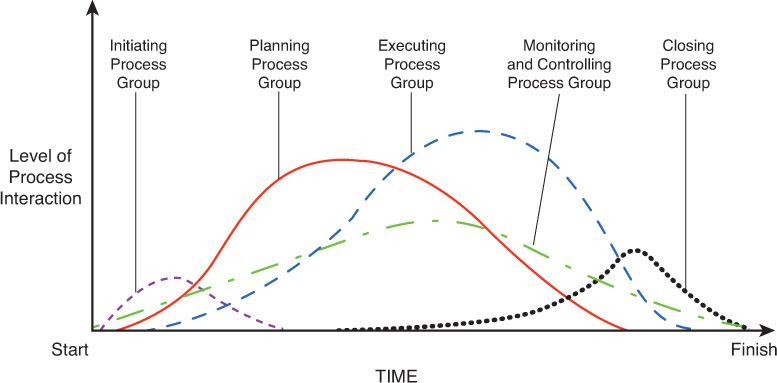

The PMBOK defines 47 project processes, grouped into five process groups. These processes define the path a project takes through its life cycle. The processes are not linear; some overlap others. In fact, some processes are iterative and are executed multiple times in a single project. It is important to become comfortable with the process flow and how it defines the project life cycle.

Throughout the life of a project, different processes are needed at different times. A project starts with little activity. As the project comes to life, more tasks are executed and more processes are active at the same time. This high level of activity increases until near the completion of the project (or project phase). As the end nears, activity starts to diminish until the termination point is reached.

Figure 1.5 shows how the process groups interact in a project.

Processes, Process Groups, and Knowledge Areas

The best way to prepare for questions that test your knowledge of the project management processes is to know and understand each of the processes, along with its process group and knowledge area assignment.

Note

You might notice that the process numbering starts with 4.1. The numbers refer to the sections in the PMBOK where each process is defined. The first three chapters in the PMBOK cover introductory material, the project life cycle, and a high-level overview of project processes. Chapters 4 through 13 cover each of the project processes in detail, organized by knowledge area. So, the first chapter in which you will find project process details is Chapter 4.

Table 1.4 shows how all 47 processes are grouped by process group and are related to the knowledge areas.

Understanding Process Interaction Customization

The five process groups defined in the PMBOK are general in nature and common to projects. However, all projects are unique, and some do not require all 47 individual project processes. The processes defined in the PMBOK are there for use when needed. You should need the majority of the processes to properly manage a project, but in some cases you will not require each process.

Because projects differ from one another, a specific process can differ dramatically between projects. For example, the process of developing a communication plan is simple and straightforward for a small project with local team members. However, the process is much more involved and complicated if the team is large and located in several countries.

Understand the five process groups and 47 processes as defined in the PMBOK. But, more importantly, understand when and how to use each process. The exam focuses more on process implementation than on process memorization. Be prepared to really think about which processes you need for a particular project.

What Next?

If you want more practice on this chapter’s exam topics before you move on, remember that you can access all of the Cram Quiz questions on the CD. You can also create a custom exam by topic with the practice exam software. Note any topic you struggle with and go to that topic’s material in this chapter.