Compositing has become the umbrella description of one of the oldest techniques in film and television production, namely, the combining of two or more separate images into one unified image. The aim of the technique is to eliminate any indication in the final composite image of the join between the separate images that have been combined.

Electronic keying, using a luminance key (off black or white), was superseded by colour separation – chroma keying using a saturated colour, usually blue. Later variants such as linear keying allowed realistic semi-transparent effects such as transparent shadows and partial reflections.

The growth of digital post-production allowed enormous flexibility in rearranging, combining and manipulating the structure of an image. Modern techniques allow digital keying, matting, painting, retouching, rotoscoping, image repair of keying and the combining of real and computer-generated backgrounds.

In all these techniques, a ‘seamless’ technique is the target. The aim is an invisible join between two or more images.

Electronic keying

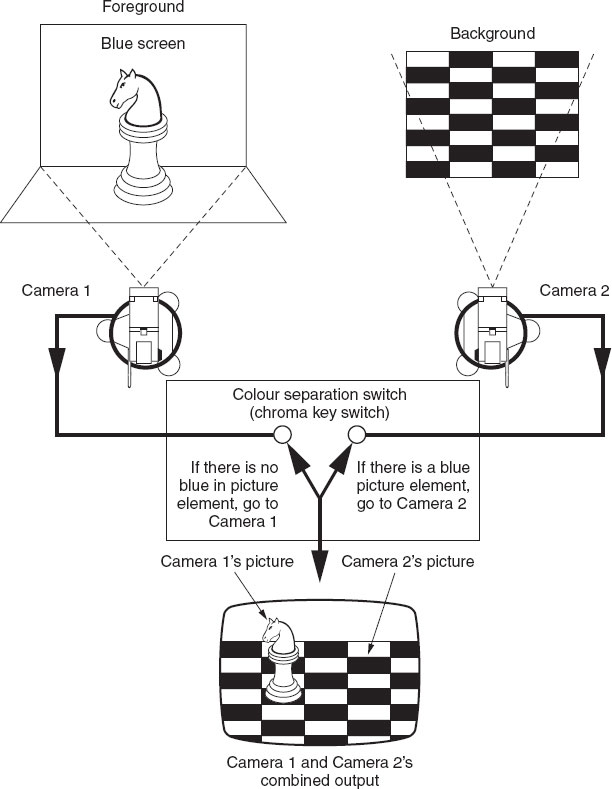

Combining two images requires a switch to be inserted in the signal chain which will electronically select the appropriate image. Blue is commonly chosen as the colour to be used as the separation key but other colours can be employed. When the chroma key switch is in use, any blue in the selected image (foreground) is switched out and replaced with the corresponding area of a chosen background scene.

Linear keying is similar to a film travelling matte system and does not switch between foreground and background. It suppresses the unwanted colour of the foreground (e.g. blue) and turns on the background image in proportion (linearly) to the brightness of the blue of the foreground image. Shadows cast by foreground objects can therefore be semi-transparent rather than black silhouettes.

Invisible keying of one image into another requires the application of a perfect electronic switch obtained by appropriate lighting of foreground and background, correct setting up and operation of the keying equipment, a match between foreground and background mood and atmosphere which is achieved by lighting and design, appropriate costume and make-up of foreground artistes, a match between foreground artiste’s size, position and movement and background perspective achieved by camera position, lens and staging.

The following pages will centre on compositional techniques to achieve a match between foreground artiste’s size, position, movement and background perspective and staging for live action that can be employed to persuade the viewer that no technique has been employed.

Combining two images requires a switch to be inserted in the signal chain which will electronically select the appropriate image. Blue is commonly chosen as the colour to be used as the separation key but other colours can be employed.

When the chroma key switch is in use, any blue in the selected image (foreground) is switched out and that part of the frame which contained blue is replaced with the background image.

Two- and three-dimensional backgrounds

Two-dimensional backgrounds

The simplest type of chroma or linear key camerawork is placing a presenter beside a primary colour panel and keying in a logo or a diagram such as a weather chart. As the infill image only exists in two dimensions, there is no problem with matching the perspective of the presenter (foreground) with the perspective of the keyed-in image (background). The foreground camera will shoot all or part of the blue screen and any person or object placed in front of the screen will overlap or be ‘in front’ of the image that is keyed into the panel. The background weather chart can be generated by another camera simultaneously with the foreground camera. Combining the two images simply involves the foreground camera adjusting the framing to contain any artiste movement. The background camera then adjusts its framing so that the required information fits the keyed area in the foreground shot.

Obviously, once this match has been achieved, neither camera can move without revealing that what appears to be a single image is in fact a composite of two different shots. Usually the weather chart will have been generated by computer graphics and keyed into the blue screen ‘window’ direct.

Any visual source – camera, frame store, computer graphics, VTR, film – can be used for a key background and the image can be moving or static. The production intention with this type of composite is to persuade the viewer that the presenter is standing beside the weather chart and can point and touch any relevant part of it.

Matching perspective of line and mass

The problems associated with keying a two-dimensional graphic into a picture are fairly straightforward compared to trying to achieve a realistic composite of two separate images. A pre-recorded background is often used either because of lack of floor space or lack of budget.

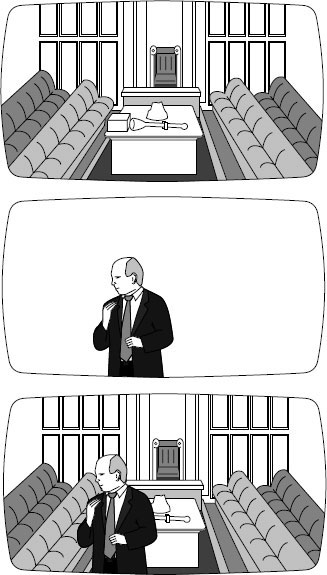

A typical example of compositing occurred in a production based on the life of a politician. The story required the statesman at one point to be in a deserted House of Commons. Because of the width of shot required, it would have been too expensive to build a replica of the Commons so therefore a recording of the Commons interior was made and then keyed into the blue screen in front of which the actor made the required movement.

The problem is exacerbated if there is actor movement towards or away from the foreground camera. If the match is incorrect, then it appears as if he inhabits a different space from his background. Which of course in reality is the case. Matching line perspective and the perspective of mass is the essential requirement for a seamless join between the foreground and background image.

The composite image combined the space recorded by the location camera with the space occupied by the actor in the studio. The problem is to get the actor’s studio space to be identical to the location space. If the resultant composite seeks to convince the viewer that both background and foreground are contiguous – that is, that they are adjacent and are observed from the same viewpoint, then the line perspective of both images will have to match in every particular. It is matching the line and mass perspective of two images, especially if the background is pre-recorded and not subject to adjustment, that often causes the most problems in shooting on blue screen.

Background/foreground camera height

Our normal perceptual experience of someone of our own size moving on flat ground towards us is that the horizon line will always intersect them at eye level. We have to duplicate this condition in the studio when the horizon line will be a separate image to an actor moving towards the lens. We have to ensure that our everyday experience of a three-dimensional world is convincingly reproduced when the three dimensions are recorded as two separate two-dimensional images and then combined.

In terms of a perspective match on blue screen, the lens axis height and tilt becomes as important in achieving an invisible join as the ‘crossing the line’ conventions of picture editing. A jump cut across the line will register just as the wrong lens height may show up when actor movement is involved.

If the lens height of the level background camera was at eye level, say 1.5 m, then everyone in the foreground studio shot needs to be intersected at eye level by the keyed or matted horizon line so they may move naturally towards and away from the camera.

Their position in the frame, relative to the background horizon line, follows our normal expectations of people walking on level ground. They must appear to grow progressively larger commensurate with their walking speed and their head must stay in the same relation to background horizon line. It must follow the horizontally parallel line from our eye (the lens) to the horizon. They must not cross the line.

If the foreground camera lens is higher than the background lens then a figure moving towards the camera will appear to be walking downhill and conflict with our expectations. Their head will start in frame above the horizon line and the end of their movement will take their head below the horizon line. This is identical with our perception of a person walking downhill even though the actor will be walking on a flat studio floor.

Likewise if the foreground camera is set too low then an approaching figure to camera will appear to be walking uphill. It is important to realize that it is not a differing lens angle or subject distance that is causing this mismatch but lens height. Tracking the camera in or out, zooming in or out or tilting will not improve the perspective match until the foreground camera is at the same height as the camera that recorded the horizon.

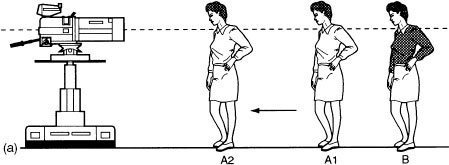

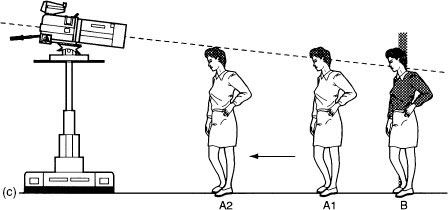

(a) With level camera and lens at eye height, person A, walking to camera on level ground, will always have their eyes at the same height in the frame as person B (assuming A and B are of the same height).

(b) The same shot is now duplicated on blue screen with A on the foreground camera and B is keyed into the background. If the foreground camera’s height, lens tilt, subject distance and lens angle match the background camera’s, A’s walk will be appropriate to the space depicted in the keyed-in background.

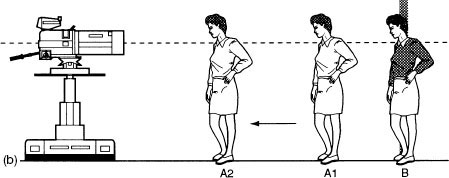

(c) The same blue screen set-up as in (b) but the foreground camera lens height is too high and therefore the height of the projected line between A and B changes during A’s walk. This produces the impression that A is walking downhill. Her head moves progressively lower in the frame as she approaches the lens in relation to the position of B’s head.

Matching foreground to background

Working with illustrations

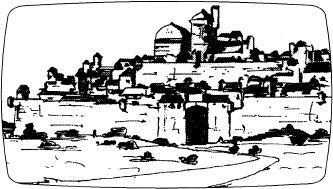

The castle and its surrounding countryside is a perfectly convincing representation of a landscape, see (a) opposite. But keying the boy walking in this ‘illustrated’ space requires the boy to follow the drawn perspective.

It is a matter of determining the lens height and lens angle and staging the boy’s walk so that it follows the drawn path. A speedy way of finding the path on the studio floor is to first determine the camera height. Then have a similar size stand-in positioned at the start of the walk and at the end of the walk to find camera distance. You will remember this determines size relationships. Then adjust the final overall framing with the zoom.

If he walks on the path with giant strides, then the camera is too close. Track out and zoom in. If he covers too little space for the length of his stride, then the camera is too far away. Track in and zoom out. If he floats across the path, then the camera is too high – crane down. If his feet sink into the path – crane up.

It is worth repeating that size relationships within the frame are the product of camera distance from the subject not the lens angle. If a two shot was taken on a wide angle lens and, without moving the camera, the same two people were taken on a narrow angle lens, their relative size relationship would be the same in both shots.

Confusion arises with this simple point because in attempting to match the foreground figure size on opposite ends of the zoom it is necessary to move the camera close to the subject to fill the frame when using the wide angle lens. It is the simple fact of moving the camera closer to the subject which changes the size relationship not the lens angle.

The important point to remember is that subject size relationship is a product of camera distance. How the subject fills the frame is a product of lens angle.

The need to quote lens angle vs focal length

Foreground and background cameras should attempt to use the same lens angle but this need not necessarily be the same focal length. Lens angle or angle of view is related to the focal length of the lens and the format size of the pick-up sensor whether it be tube, chip or film gate. A 50 mm lens on a 35 mm stills camera will not produce the same angle of view as a 50 mm zoom lens setting on a Betacam, whereas the lens angle of a 50 mm lens on a 16 mm film camera will match the 32 mm focal length setting on a ½ inch CCD camera and provide similar perspective of mass, assuming all other factors are equal.

Angle of view is therefore best stated in degrees rather than the dimension of the focal length of a lens when matching two different formats.

(a) Background with a drawn path

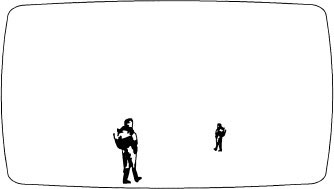

(b) Boy in studio walking against blue screen with no line showing between floor and background. His walk must follow the drawn path in the illustration above (a). The second figure is a stand-in to find the end position of the boy’s walk. The size of background figure will be determined by camera distance/height and must match the perspective of background. As the boy walks towards this second position his change in size and his position in the frame must match the drawn background.

(a) and (b) combined into a single shot with the boy appearing to follow the drawn path with the appropriate reduction in size as he walks away from camera.

Camera movement on blue screen

Camera movement

When a foreground artiste is composited with a background image, any camera movement by the foreground camera will displace the artiste in relation to the background, unless the camera providing the background image also duplicates the foreground movement, and vice versa.

Panning on the background image will ‘fly’ the foreground figure through space. To achieve natural movement of a combined image both foreground and background movement have to be in perfect synchronization. The synchronization must provide not only for the same ratio of change in picture size in background and foreground image but a perfect match in perspective change.

Synchronization of perspective change is therefore almost impossible to achieve with manually operated cameras but can be guaranteed with a motion control rig which is a motorized crane where all movement of its lens in space is computer controlled.

Memory heads

Precise duplication of movement of background and foreground images to ensure that the combined image stays in register during camera movement can also be achieved by using a special pan and tilt head that records each movement on a computer disk.

The background scene can be pre-recorded using a memory head and all the essential data that we have talked about, namely lens height, lens angle, tilt, distance from subject, speed of pan, tilt, zoom movement, speed of zoom and focus, can be memorized on a floppy disk which can then be used to program the foreground camera to duplicate camera moves on the foreground subject on blue. It can also be used to synchronize two camera movements so that there is no image slip between the composited shots.

Virtual studios

As the cost of computing power decreases, more and more facilities utilizing enormous amounts of computer memory are available for production. Virtual scene construction allows an artiste moving on a blue screen background to be composited into a background electronically created or based on a still.

The foreground camera capturing the artiste on blue can pan, track and move with the subject and the computer software will automatically alter the background accordingly. The distance from camera to presenter is continuously calculated and fed to the computer. This allows them to appear to walk behind and in front of computer-generated graphic ‘objects’ (such as simulated furniture), which is composited into the shot.

The claim for the virtual reality studio is that it can exist simply as a blue screen studio whilst its keyed ‘scenery’ will be held in the computer to be changed, depending on programme format, at the touch of a button. The system allows more than one camera to be used and to be routed as normal through a mixing panel for intercutting. Each shot will have the appropriate section of the computer-generated set as background.

Differential focus

A simple technique for creating depth on a composite sequence is differential focus. By throwing the background out of focus a better foreground to background match can be achieved. This simulates the depth of field that is normally available on close ups. Throwing the background out of focus also helps for better edits using portions of the same illustration. Another point to bear in mind with depth of field is the need to create a believable focus-zone gradation between background and foreground. It might be necessary to pre-record the background slightly out of focus to match the foreground action depending on size of shot on foreground actor. An everyday example of this is the newsreader in front of blue with a keyed-in picture of a defocused newsroom.

Background problems

If the foreground camera is limited in its framing by the restraints of matching both the linear perspective and mass perspective there are situations where a difficult or unacceptable framing arises.

A foreground figure will be either too high or too low in the frame and the camera is unable to tilt or crane to compensate because this will destroy the perspective match. Typically this happens if there is a high horizon and low lens height on the background camera and an artiste walks towards the foreground camera. The result is crushed headroom on foreground with no way of compensating.

The reverse produces the opposite problem. A low horizon and above eye line lens height on the background camera will create excessive headroom in foreground as the subject moves towards camera. Little or nothing can be done by the foreground camera to provide a more acceptable framing. The solution lies in changing the background to fit the required foreground framing and/or restaging the foreground action. This may cause a serious problem that could be avoided by production pre-planning.

It is important to remember that the lens height, lens angle, camera distance from subject and camera tilt recording the background will control and constrain any subsequent foreground movement on chroma key.