Invisible cuts

Continuous camera coverage of an event using a number of cameras relies on a stream of invisible shot changes in the sense that the transition between each shot does not distract the audience. The aim is to make the shot change unobtrusive to prevent the audience’s attention switching from programme content to the programme production technique. Although individual camera operators frame up their own shots, the pictures they produce must fit the context of the programme and match what other camera operators are providing. No shot can be composed in isolation – its effect on the viewer will be related to the preceding and succeeding shot. The camera operator is directly involved in edit point decisions (see the use of the mixed viewfinder in Viewfinder, page 164).

Why use more than one camera?

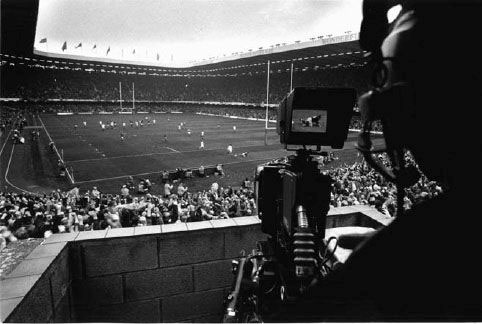

If intercutting between cameras is potentially distracting to the viewer, why change the shot? Many football matches, for example, are covered by a single camera for news and sports reports but there are inherent problems with this technique. Close shots capture the excitement and personalities in the match whereas wide shots reveal tactics and the flow of the game. A single camera has to resort to zooming in and out continuously in order to provide both types of shots. If the game is shot continuously wide, then it lacks excitement. If it is shot too close, then there is the risk of missing vital action (like goals!). It is around the goal area that the single camera operator has to chance his/her arm. Zoom in for the expected goalkeeper save and the camera operator may miss the ball rebounding out to another player who scores from outside the frame.

Choice of shot

Multi-camera coverage of sport allows a director the option of choosing the size of shot and camera angle to match the action. With a five or six camera coverage of football, for example, as the action moves towards the goal area, each of the six cameras will have a designated role providing a range of close and wide shots which can be instantly cut to depending on the outcome of the attack. Many of the cameras will be isoed (their individual output continuously recorded) to provide instant replay in slow motion.

Editing decisions

Particularly in as-directed situations such as sport, discussion and many forms of music, etc., the camera operator must anticipate the shot structure and provide the right composition and choice of shot to satisfy standard editing requirements. Intercutting between cameras in multi-camera coverage occurs in real time without the benefit of the more extended decisionmaking time about edit points enjoyed in post-production. The timescale of the event covered dictates intercutting decisions and the shot rate (e.g. a 100 m race is covered in under 10 seconds, a 5000 m race in approximately 13 minutes).

Multi-camera sports coverage

This type of sports coverage is fluent and flexible and should miss no important incident. In comparison, single camera coverage of similar events is at a considerable disadvantage.

What makes a shot change invisible?

Multi-camera coverage of an event involves intercutting between a variety of camera angles in order that different aspects of the event can be transmitted. If intercutting is badly done, then changes of shot are conspicuous and switch attention to the technique.

For a shot change to be unobtrusive:

![]() there must be an appropriate production reason to change the shot;

there must be an appropriate production reason to change the shot;

![]() the shots either side of the visual transition (cut, wipe, mix) must satisfy the editing requirements that link them.

the shots either side of the visual transition (cut, wipe, mix) must satisfy the editing requirements that link them.

Production reasons for a shot change

There are many production reasons for changing the shot. These include:

![]() following the action (e.g. coverage of horse racing: as the horses go out of range of one camera, they can be picked up by another);

following the action (e.g. coverage of horse racing: as the horses go out of range of one camera, they can be picked up by another);

![]() presenting new information (e.g. a wide shot of an event shows the general disposition, a close-up shows detail);

presenting new information (e.g. a wide shot of an event shows the general disposition, a close-up shows detail);

![]() emphasizing an element of the event (e.g. a close-up shot revealing tension in the face of a sports participant);

emphasizing an element of the event (e.g. a close-up shot revealing tension in the face of a sports participant);

![]() telling a story (e.g. succeeding shots in a drama);

telling a story (e.g. succeeding shots in a drama);

![]() providing pace, excitement and variety in order to engage and hold the attention of the audience (e.g. changing the camera angle and size of shot on a singer);

providing pace, excitement and variety in order to engage and hold the attention of the audience (e.g. changing the camera angle and size of shot on a singer);

![]() structuring an event visually in order to explain (e.g. a variety of shots on a cooking demonstration that shows close-ups of ingredients and information shots of the cooking method).

structuring an event visually in order to explain (e.g. a variety of shots on a cooking demonstration that shows close-ups of ingredients and information shots of the cooking method).

In an as-directed camera coverage where the camera operator is finding and offering shots for the director to select, the nature of the shots must coincide with the specific programme format and include a reason to change the shot. For example, it is unlikely that a big close-up of the presenter’s face that fills the screen would be required during a cookery demonstration whereas it might be entirely appropriate before match point in a Wimbledon final (see Assessing a shot, page 186).

What are the edit requirements for a good cut?

A good cut usually satisfies the audience’s expectations. If someone speaks out of frame at some time, the audience will want to see them. For dramatic reasons, curiosity about the unseen voice can be intensified by delaying the cut, but this is not usually a requirement in a standard TV interview.

Editing conventions sometimes rely on everyone involved in the production having a knowledge of well-known shot patterns such as singles, two shots, over the shoulder two shots, etc. in the standard camera coverage of an interview. This speeds up programme production when matching shots of people in discussion either in factual or fictional dialogue and allows fast and flexible team working because everyone is aware of the conventions.

In general a change of shot will be unobtrusive

![]() if there is a significant change in shot size or camera angle (camera position relative to subject) when intercutting on the same subject;

if there is a significant change in shot size or camera angle (camera position relative to subject) when intercutting on the same subject;

![]() if there is a significant change in content (e.g. a cut from a tractor to someone opening a farm gate);

if there is a significant change in content (e.g. a cut from a tractor to someone opening a farm gate);

![]() when cutting on action – the flow of movement in the frame is carried over into the succeeding shot (e.g. a man in medium shot sitting behind a desk stands up and on his rise, a longer shot of the man and the desk is cut to);

when cutting on action – the flow of movement in the frame is carried over into the succeeding shot (e.g. a man in medium shot sitting behind a desk stands up and on his rise, a longer shot of the man and the desk is cut to);

![]() when intercutting between people if their individual shots are matched in size, have the same amount of headroom, have the same amount of looking space if in semi-profile, if the lens angle is similar (i.e. internal perspective is similar) and if the lens height is the same (see Cross shooting, page 158);

when intercutting between people if their individual shots are matched in size, have the same amount of headroom, have the same amount of looking space if in semi-profile, if the lens angle is similar (i.e. internal perspective is similar) and if the lens height is the same (see Cross shooting, page 158);

![]() if the intercut pictures are colour matched (e.g. skin tones, background brightness, etc.) and if in succeeding shots the same subject has a consistent colour (e.g. grass in a stadium);

if the intercut pictures are colour matched (e.g. skin tones, background brightness, etc.) and if in succeeding shots the same subject has a consistent colour (e.g. grass in a stadium);

![]() if there is continuity in action (e.g. body posture, attitude);

if there is continuity in action (e.g. body posture, attitude);

![]() if there is continuity in lighting, in sound, props and setting and continuity in performance or presentation.

if there is continuity in lighting, in sound, props and setting and continuity in performance or presentation.

Matched shots on an interview

Multi-camera coverage of an interview is about the most widespread format on television after the straight-to-camera shot of a presenter. The staging of an interview usually involves placing the chairs for good camera angles, lighting, sound and for the ease and comfort of the guests and the presenter. The space between people should be a comfortable talking distance.

Eyeline

Eyeline is an imaginary line between an observer and the subject of their observation. In a discussion, the participants are usually reacting to each other and will switch their eyeline to whoever is speaking. The viewers, in a sense, are silent participants and they will have a greater involvement in the discussion if they feel that the speakers are including them in the conversation. This is achieved if both eyes of the speaker can be seen by the viewer rather than profile or semi-profile shots. The cameras should be able to take up positions in and around the set to achieve good eyeline shots of all the participants: both eyes of each speaker, when talking, can be seen on camera.

In addition, the relationship of the participants should enable a variety of shots to be obtained in order to provide visual variety during a long interview (e.g. over the shoulder two shots, alternative singles and two shots and group shots, etc.). The staging should also provide for a good establishment shot or relational shot of the participants and for opening or closing shots.

Standard shot sizes

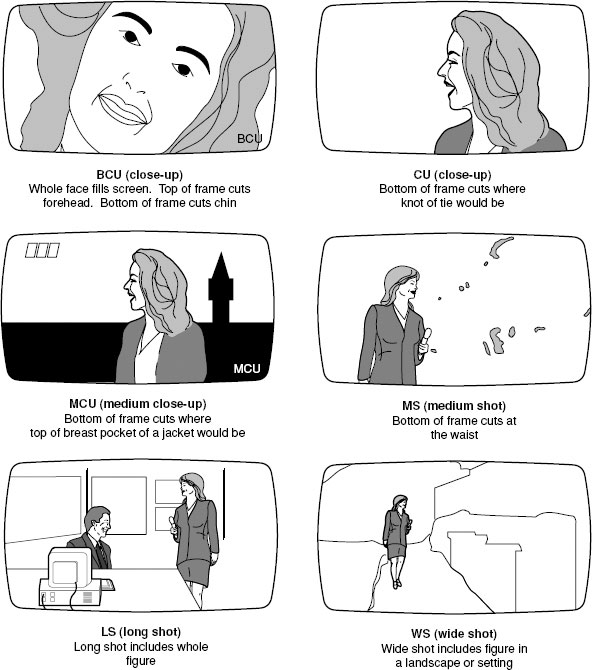

Because so much of television programming involves people talking, a number of standard shot sizes have evolved centred on the human body. In general, these shot sizes avoid cutting people at natural joints of the body such as neck, elbows, knees. Normal interview shots include:

![]() CU (close-up) bottom of frame cuts where the knot of a tie would be;

CU (close-up) bottom of frame cuts where the knot of a tie would be;

![]() MCU (medium close-up) bottom of the frame cuts where the top of a breast pocket of a jacket would be;

MCU (medium close-up) bottom of the frame cuts where the top of a breast pocket of a jacket would be;

![]() MS (medium shot or mid shot) bottom of frame cuts at the waist.

MS (medium shot or mid shot) bottom of frame cuts at the waist.

Other standard shot descriptions are:-

![]() BCU (big close-up). The whole face fills the screen. Top of frame cuts the forehead. Bottom of the frame cuts the edge of chin avoiding any part of the mouth going out of frame (rarely used in interviews).

BCU (big close-up). The whole face fills the screen. Top of frame cuts the forehead. Bottom of the frame cuts the edge of chin avoiding any part of the mouth going out of frame (rarely used in interviews).

![]() LS (long shot). The long shot includes the whole figure.

LS (long shot). The long shot includes the whole figure.

![]() WS (wide shot). A wide shot includes the figure in a landscape or setting.

WS (wide shot). A wide shot includes the figure in a landscape or setting.

![]() O/S 2s (over the shoulder two shot). Looking over the shoulder of a foreground figure framing part of the head and shoulders to another participant.

O/S 2s (over the shoulder two shot). Looking over the shoulder of a foreground figure framing part of the head and shoulders to another participant.

![]() two shot, three shots, etc., identifies the number of people in frame composed in different configurations.

two shot, three shots, etc., identifies the number of people in frame composed in different configurations.

Note: precise framing conventions for these standard shot descriptions vary with directors and camera operators. One man’s MCU is another man’s MS and can give rise to shot descriptions such as a ‘loose MS’ or a ‘tight MS’ etc. Check that your understanding of the position of the bottom frame line on any of these shots shares the same size convention for each description as the director with whom you are working.

Standard shot sizes

A standard cross-shooting arrangement is for the participants to be seated facing each other and for cameras to take up positions close to the shoulders of the participants (see opposite).

The usual method of finding the optimum camera position is to position the camera to provide a well-composed over the shoulder two shot then zoom in to check that a clean single can be obtained of the participant facing camera. A tight over the shoulder two shot always risks masking or a poorly composed shot if the foreground figure should lean left or right. To instantly compensate, if this should occur, set the pedestal steering wheel in a position to allow crabbing left or right for rapid repositioning on or off shot.

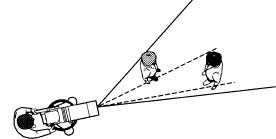

Crossing the line

There may be a number of variations in shots available depending on the number of participants and the method of staging the discussion/interview. All of these shot variations need to be one side of an imaginary line drawn between the participants.

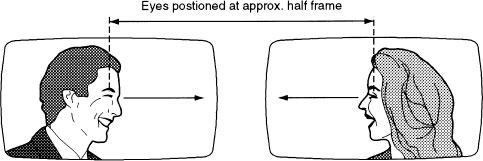

To intercut between individual shots of two people to create the appearance of a normal conversation between them, three simple rules have to be observed. Firstly, if a speaker in a single is looking from left to right in the frame, then the single of the listener must look right to left. Secondly, the shot size and eyeline should match (i.e. they should individually be looking out of the frame at a point where the viewer anticipates the other speaker is standing). Finally, every shot of a sequence should stay the same side of an imaginary line drawn between the speakers (see diagram opposite) unless a shot is taken exactly on this imaginary line or a camera move crosses the line and allows a reorientation (and a repositioning of all cameras) on the opposite side of the old ‘line’.

Matching to other cameras

In addition to setting up the optimum position for singles, two shots, etc., camera operators in a multi-camera intercutting situation need to match their shots with the other cameras. The medium close-ups (MCU), etc., should be the same size with the same amount of headroom. All cameras intercutting on singles should be the same height and if possible roughly the same lens angle (therefore the same distance from their respective subjects) especially when intercutting on over the shoulder two shots. This avoids a mismatch of the perspective of mass (i.e. the background figure is smaller or larger than the shot it is matching to). Other matching points are the same amount of looking room with semi-profile shots by placing the centre of the eyes (depending on size of shot) in the centre of frame.

The best method of matching shots is to use the mixed viewfinder facility or check with a monitor displaying studio out.

Camera positions for an interview

First set the camera position for a good over the shoulder two shot and then check that a clean MCU (i.e. the foreground head does not intrude into the MCU frame) can be obtained without repositioning the camera.

Crossing the line

Because of the unrehearsed nature of a discussion, each camera takes up a position where it can match its shots to other cameras plus have the flexibility to offer more than one size of shot without repositioning. Constant camera repositioning during an interview can result in gaps in the camera coverage leading to participants talking in long shot because the camera that should be providing their closer shot is on the move.

Camera 4, looking for ‘interesting shots’, has gone upstage of the imaginary line(s) that connects the participants eyelines. When intercut with Camera 3, two people who, in the studio, are looking at each other (and therefore in opposite directions) will appear on screen to be both looking in the same direction. If cameras on both sides of the line are continually intercut, the viewer quickly loses the geographic relationship of the participants. Also, Camera 4 has created a problem for Camera 3 who is very close to being in Cameras 4’s shot. By taking up such a position, Camera 4 has also pushed Camera 3 downstage to keep out of shot and forced Cameras 2 and 3 off their optimum eyeline position on the guests. Multi-camera camerawork is a team effort and any individual camera move or shot usually affects the work of the rest of the camera crew.

A production situation where matched shots and a shared understanding of the conventions of shot structure is required by camera operators is the television interview/discussion between two, three or many participants. Although the rehearsal procedure may vary, there is usually a requirement for the following production details to be agreed before transmission or recording.

The director uses the rehearsal time to check or inform the crew about the following:

![]() Establish on which camera the presenter will introduce and wind up the interview and in what order he/she will introduce and question the guests.

Establish on which camera the presenter will introduce and wind up the interview and in what order he/she will introduce and question the guests.

![]() Establish if there are any props or visual material that will be referred to. Agree on the cue words for their introduction of this material and decide which camera will cover the close-ups.

Establish if there are any props or visual material that will be referred to. Agree on the cue words for their introduction of this material and decide which camera will cover the close-ups.

![]() Check the range of shots available from all cameras and tell the cameramen which are likely to be used.

Check the range of shots available from all cameras and tell the cameramen which are likely to be used.

![]() Match camera shot sizes.

Match camera shot sizes.

![]() Rehearse the beginning and end of the programme and any entrances and exits. It is usually unnecessary and unproductive to rehearse the interview. Voice levels are checked by sound and the guest’s appearance and clothing are checked by lighting/vision control prior to recording or transmission.

Rehearse the beginning and end of the programme and any entrances and exits. It is usually unnecessary and unproductive to rehearse the interview. Voice levels are checked by sound and the guest’s appearance and clothing are checked by lighting/vision control prior to recording or transmission.

![]() It may be necessary for the camera crew and director to agree on standard shot size and abbreviation to avoid misunderstanding during transmission/recording. Abbreviation of shot descriptions (MCU, MS, etc.) are used so that shot size can be quickly changed.

It may be necessary for the camera crew and director to agree on standard shot size and abbreviation to avoid misunderstanding during transmission/recording. Abbreviation of shot descriptions (MCU, MS, etc.) are used so that shot size can be quickly changed.

![]() There is often a convention by the director to state camera number first (e.g. ‘Camera 3’) and then the instruction (‘two shot please’).

There is often a convention by the director to state camera number first (e.g. ‘Camera 3’) and then the instruction (‘two shot please’).

![]() During the rehearsal the camera operators will take the opportunity to look at all potential shots from their camera position and keep the director informed if he/she is requesting shots which cause problems or are more easily obtained on other cameras. They will also make certain, if they are on the ‘live’ side of the microphone, that they keep physical movement/noise to a minimum and that their camera position will not produce shadows on any part of the set in shot. Offer a two shot so that a lighting balance can be established.

During the rehearsal the camera operators will take the opportunity to look at all potential shots from their camera position and keep the director informed if he/she is requesting shots which cause problems or are more easily obtained on other cameras. They will also make certain, if they are on the ‘live’ side of the microphone, that they keep physical movement/noise to a minimum and that their camera position will not produce shadows on any part of the set in shot. Offer a two shot so that a lighting balance can be established.

![]() A repositioning of a camera between shots which takes an appreciable time should be carefully considered on rehearsal as frequently, in a spontaneous event such as an interview, there is little or no time during transmission/recording to provide time for such a reposition. It can result in a participant talking out of shot as one or two cameras are taking up new positions. If asked by the director how long a reposition will take, estimate the time for the move and add ten seconds for safety.

A repositioning of a camera between shots which takes an appreciable time should be carefully considered on rehearsal as frequently, in a spontaneous event such as an interview, there is little or no time during transmission/recording to provide time for such a reposition. It can result in a participant talking out of shot as one or two cameras are taking up new positions. If asked by the director how long a reposition will take, estimate the time for the move and add ten seconds for safety.

![]() The importance of offering different sized shots in order to get a good cut.

The importance of offering different sized shots in order to get a good cut.

![]() The narrative ‘weight’ of a shot is dependent on the size of the shot and also on the composition. Emphasis can be strengthened or lightened depending on the reason for the shot.

The narrative ‘weight’ of a shot is dependent on the size of the shot and also on the composition. Emphasis can be strengthened or lightened depending on the reason for the shot.

![]() Decisions on the composition of a shot will have to consider how the shot relates in size, lens position, continuity (body posture, position, etc.), linked movement, crossing the line relationships, lighting, mood, atmosphere with the preceding and succeeding compositions.

Decisions on the composition of a shot will have to consider how the shot relates in size, lens position, continuity (body posture, position, etc.), linked movement, crossing the line relationships, lighting, mood, atmosphere with the preceding and succeeding compositions.

Looking room

Balanced ‘looking room’ on intercut shots

![]() During rehearsal, the floor manager will confirm with the presenter how he/she will signal when to move on to the next question (if needed), how he/she will signal the time to the end of the programme and the signal for any other instruction that the director may want to pass on. They will make certain that they stand in the presenter’s eyeline so that the presenter can see their cues and signals. They should check that their arm movements do not produce shadows on the set. Frequently the presenter will be fitted with an ear-piece with direct talkback from the director and/or producer/editor. Either floor manager or presenter will brief the guests to ignore the cameras and studio and speak to the anchor person.

During rehearsal, the floor manager will confirm with the presenter how he/she will signal when to move on to the next question (if needed), how he/she will signal the time to the end of the programme and the signal for any other instruction that the director may want to pass on. They will make certain that they stand in the presenter’s eyeline so that the presenter can see their cues and signals. They should check that their arm movements do not produce shadows on the set. Frequently the presenter will be fitted with an ear-piece with direct talkback from the director and/or producer/editor. Either floor manager or presenter will brief the guests to ignore the cameras and studio and speak to the anchor person.

![]() The floor manager also checks that all studio doors are closed and everyone is present before recording or transmission commences.

The floor manager also checks that all studio doors are closed and everyone is present before recording or transmission commences.