| 8 | Charts, Airplay and Promotion |

The connection between recorded music and radio is essential to the success of large record labels that compete in the national and international mass markets. This chapter will show this key connection by providing an understanding of how the charts of trade magazines are developed, followed by a view of how those who are responsible for radio promotion at a label can influence those charts.

The two major trade magazines for the music industry are Billboard and Radio & Records. Both provide comprehensive weekly views of the recording industry, the music business, and commercial radio.

Billboard Magazine was first introduced in 1894 as a publication providing information about the carnival industry, but began to focus more on music and less on carnivals. In 1936, it published its first “hit parade,” which was a term used at the time to rank popular songs and then became a term used by radio to denote its most popular music (Ammer, C., 1997). In 1940, Billboard compiled and published its first Music Popularity Chart, and by 1958 the venerable Hot 100 chart became a staple of the magazine (wikipedia.org, 2005).

Gavin and Cashbox magazines were key industry trade publications for many years until they were retired for economic reasons. Both of these trades relied upon “reported” airplay by radio stations that gave the publications their airplay charts for the coming week. In October 1973, Radio & Records published its first issuei and has been Billboard’s major competition since.

Perhaps the most important piece of real estate a record label can own is a high chart position in trade magazines for its albums and singles. A favorable airplay chart position from record industry trade magazines like Billboard and R&R has the same effect as a “word of mouth” endorsement of recordings because it is a reflection of the opinions of key radio program directors.

Charts in trade magazines are defined in numerous ways, and it is important to be sure the distinction is made between sales charts and airplay charts. If a label has a number one album, that placement is based on its position on a sales chart. If a label has a number one single on the radio, that position is based upon the number of times a single is played on the radio during a specific week, and how big the cities are in which the song is played.

In the next part of this chapter, we will look at how charts are created and why they are so important to the marketing of recordings.

Nearly every major music genre has an airplay chart in the two major trade magazines. These charts are a reflection of national airplay of singles on radio stations as detected by two somewhat different systems (except for some specialty charts).

Broadcast Data Systems (BDS)

Broadcast Data Systems (BDS) is the technology used by Billboard and Canadian Music Network magazines to detect each spin of a recording on radio in cities in which they have installed a computer to monitor airplay. As the spins are detected, the computers upload the number of detections to a main database that is then used to create the weekly airplay charts. Geoffrey Hull cites Billboard describing the system as:

A proprietary, passive, pattern-recognition technology that monitors broadcast waves and recognizes songs and/or commercials aired by radio and TV stations. Records and commercials must first be played into the system’s computer, which in turn creates a digital fingerprint of that material. The fingerprint is downloaded to BDS monitors in each market. Those monitors can recognize that fingerprint or “pattern,” when the song or commercial is broadcast on one of the monitored stations,” (Hull, G., 2004).

As the computerized airplay monitor “listens” to a song being played on the radio, it compares its digital fingerprint to that on file, and then logs it as a detected play of the song.

BDS has monitors for airplay in 128 radio markets, and claims to listen to over 1,100 stations and detect over 1 million songs each week. These detections are used to compile 25 airplay charts for Billboard and its Airplay Monitor. Additionally, the service compiles detections of airplay on six cable and satellite channels that feature music videos.

Label marketers must be sure they register their recorded music with BDS or there will be no detections of airplay. BDS provides information on its website on how to register a song and get a digital fingerprint created for the airplay monitoring system. Without the airplay statistics, the radio promotion department will be without the bragging rights they need to continue to promote the single, and the marketing department will be without a key tracking tool (BDS, 2005).

BDS generally describes its market monitoring systems as follows:

Monitors are strategically positioned in a market to ensure that we get the best reception possible for each station in that market. Each monitor has 10–15 slots. Every slot represents a different signal and is used for either radio or television monitoring. Each station has its own library of song or advertising patterns stored in its memory. These song patterns or “fingerprints” are constantly increasing and are well over 10,000 (and counting) at the monitor site: more than 1,500 titles for country, 3,500 for modern rock and R&B, and over 4,000 for Top 40 (hipnotikent, 2004).

BDS gives the label’s marketing department considerable information about which radio stations are spinning a single and how frequently. Combining this information with SoundScan data on sales of singles, label marketers have continuing feedback on the performance of their recorded music projects. And most importantly, this feedback gives marketers the information needed to modify marketing plans in order to draw as much commercial value out of the marketplace as possible.

MediaBase is a service owned by Clear Channel Entertainment and is under exclusive contract with Radio & Records (R&R) to provide data that it then uses to create its airplay charts. It monitors the airplay of recordings on over 1,000 radio stations, including 125 in Canada (SoundSource, 2005).

While the information is very similar to that provided by BDS and is used by record labels in the same ways, there are some differences between the services. Where BDS uses computers to detect airplay, MediaBase employs people to actually listen to radio stations and log the songs played. Employees of the company who are paid to detect airplay are experts in their genres of music, they often work from their homes, and they are provided the necessary hardware and software by the company. Employees who work in airplay detection are often responsible for logging songs for the 24-hour broadcast days of eight radio stations.

Another difference in the services lies in the particular stations whose airplay is monitored. MediaBase monitors an estimated 80% of the same stations as BDS. Some record labels see the need to subscribe to both services to be sure they are getting accurate feedback on the performance of single releases at radio (radio-media, 2005).

Weekly charts representing airplay, sales, and a combination of both appear in Billboard and its related Airplay Monitor.

Billboard indicates recognition for accomplishments each week in the charts with the use of special awards. The most commonly known recognition is a bullet, which is awarded for “significant improvement in sales or airplay from the previous week.” Other designations are as follows:

Table 8.1 Billboard chart designations

A heat seeker is a special designation by Billboard for developing artists and is described on their website as:

“The Top Heatseekers chart lists the bestselling titles by new and developing artists, defined as those who have never appeared in the Top 100 of The Billboard 200 chart. When an album reaches this level, the album and the artist’s subsequent albums are immediately ineligible to appear on the Top Heatseekers chart,” (Billboard online, 2005).

“Spins” and “plays” are terms given to denote the number of times a song is played on a radio station in a set time period. R&R and Billboard magazines report spins for their reporting stations. They also report a “most added” category indicating the new songs that were added to the most stations that week. Songs that are added in light rotation (meaning they are played fewer times) to a station’s playlist are those that are either on their way up the music charts of trade magazines or on their way off of the charts. Songs that are in heavy rotation are those most popular with a station’s audience. In between, there is medium rotation. The actual number of spins necessary to be placed into one of these categories varies from format-to-format and station-to-station and is subject to change. Recurrents are songs that used to be in high rotation at a station, but are now on the way down, reduced to limited spins. Burnout (or burn) is the term given to songs that have reached a particular threshold for audience burnout as determined by radio programming research. A station may decide to remove a song from the playlist when the “burnout factor” reaches a certain percentage of the audience.

The Hot 100 has been a part of Billboard magazine since 1956, and it has spawned numerous other genre-specific charts. The Hot 100 is a chart that is developed each week using a formula that combines the physical sales of singles, sales of digital downloaded singles, as well as the number of spins a song receives on radio, regardless of the genre of music or the radio format in which the song is programmed.

Other charts published weekly by the magazine include rankings by genre, created by using data gathered for airplay through its BDS reporting system. Airplay charts are then used by radio programmers to give them a basis to compare their audience offerings with those audiences of similar cities. Also, each week Billboard publishes its Top 200 chart, which is a compilation of the bestselling albums ranked by the number of unit sales for the previous week. Both of these charts are especially important to the marketing effort by a label on behalf of its active new music projects. Tracking the impact the music is having at radio and at retail gives label marketers information that is helpful to control the success of singles and albums.

The Billboard charts are continually modified in order to keep them as an accurate reflection of the needs of the businesses they serve. In early 2005, responding to an increase in the number of audio and video content discs being marketed together, Billboard announced:

Effective with first-chart week of Nielsen SoundScan’s 2005 tracking year, Billboard is amending its dual-charting policy. Going forward, there will be far fewer titles that qualify for both album and music video charts.

The policy: Most combo or DualDisc titles will appear on either album or music video charts, not both. Titles that offer far more audio content than video content will be considered albums. Those that offer far more video content than audio content will be considered music video titles. Only in cases where the content of both the audio and video programming would both qualify as full-length product will a title appear on both charts (Nielsen SoundScan, 2005).

Another change Billboard made to some of its charts is to add a weight to the detection of the airplay of a single. This means that the time of day (audience size), and the size of the city in which a single is played will determine how important that spin is on an airplay chart. For example, a spin of a single by a radio station in Chicago during morning rush hour will be weighted more on the airplay chart than a late night spin on a small town, non-network radio station.

Among the newest charts is Billboard’s Pop 100. This chart lists only the top songs being played at top 40 radio stations and includes both airplay and sales to determine chart positions. Songs are ranked based on the number of gross impressions. This is compiled by cross-referencing the exact times the songs are played against Arbitron’s data on listenership at that time.

R&R’s charts are similar to Billboard’s in many ways. Both publications include airplay charts based on detected spins by monitored radio stations, and each reports sales data on recorded music. In addition to the charts, the two magazines provide their subscribers with considerable news and information on the music and radio industries each week.

CMJ charts are created through the CMJ Network, which refers to itself as connecting “music lovers with the best in new music through print and interactive media, as well as live events” (cmj.com, 2005). Charts for CMJ are created by reports of airplay from their “panel of college, commercial and noncommercial radio stations,” and tend to represent music that is not a part of the commercial mainstream (cmj.com, 2005). Its charts are reported in publications by the company, as well on its website and chart titles. Those charts include:

![]() CMJ Top 20

CMJ Top 20

![]() Radio 200

Radio 200

![]() Triple A Top 20

Triple A Top 20

![]() Loud Rock Top 20

Loud Rock Top 20

![]() Jazz Top 20

Jazz Top 20

![]() New World Top 20

New World Top 20

![]() RPM Top 20

RPM Top 20

![]() Retail

Retail

![]() In-Store Play

In-Store Play

What does this mean to label marketers?

The best way to demonstrate the impact of the airplay charts on label marketing is to look at the number of times people hear a single played on the radio during a week. Below is a listing showing the titles of several airplay charts in Radio & Records and the number of “impressions” that a number one record in that genre made during the week of February 4, 2005. “Impressions” means the number of times the number one song in the particular genre was heard by someone on a station monitored by MediaBase, and reported on the weekly airplay chart.

Table 8.2 Radio format and impressions |

|

Radio Format Chart |

Number of Impressions |

Contemporary Hit Radio/Rhythmic |

82,013,300 |

Contemporary Hit Radio/Pop Top 50 |

71,877,700 |

Urban Top 50 |

54,798,300 |

Country |

42,914,300 |

Urban Adult Contemporary |

12,986,600 |

Considering the weekly numbers reflected in this chart, it is obvious the immense impact commercial radio has on the exposure of recorded music to targeted potential customers of the label.

Lobbying and lobbyists have been around as long as any one person has been responsible for a decision or a vote, and people have always wanted to influence that decision or vote in their favor. Everyday, lawmakers at the national and state levels meet with representatives of special interest groups who ask them to vote on matters that are in the best interests of their groups or their clients.

The same thing happens between a radio programmer and a record promoter. The people lobbied are usually the program directors of radio stations that report their charts to the major trade magazines. Program directors, also referred to as PDs, have the ultimate responsibility for everything that a radio station broadcasts—banter by personalities, advertising, information such as news and traffic reports, and all music played by the station. Simply said, the radio programmer can decide whether a record ever gets on the air at their station.

Decisions by radio programmers are the keys to the life of a record and have become the basis for savvy, smart, and creative record promotion. Programming decisions about music determine:

![]() Whether a new recording is added to the playlist of a radio station that reports its chart and airplay to the major trade magazines.

Whether a new recording is added to the playlist of a radio station that reports its chart and airplay to the major trade magazines.

![]() Whether the recording receives at least light rotation on the playlist.

Whether the recording receives at least light rotation on the playlist.

![]() Whether it eventually receives heavy rotation on the station’s playlist.

Whether it eventually receives heavy rotation on the station’s playlist.

Record promoters are lobbyists in the purest form. They are either on the staff of a record company or they are part of a company specifically hired by the label to promote new music.

Traditional marketing texts teach the four P’s, one of which is promotion. Those same texts tell us that the promotional mix consists of public relations, advertising, sales promotion, direct marketing, and personal selling.

The definition of record promotion comes closest to being personal selling than any other aspect of the traditional promotional mix, except perhaps the label sales department. Personal selling is one-on-one, and the work of a record promoter is exactly that. The record promotion person at a record label has the responsibility of securing radio airplay for the company’s artists. Quite simply, they lobby the station decision makers to add recordings by the label’s artists to the station’s playlist. With some label executives claiming that radio is responsible for 70% of sales of recorded music, label record promotion can be critical to the success of an album project. It is this close connection between airplay and record sales that creates the need for record promotion to radio as a key element of the marketing plan.

The effectiveness of a record promotion person hinges on the strength of the relationships he or she has with radio programmers. These relationships are built much like anyone in business that has a client base requiring regular service. The promoter makes frequent calls in person and by telephone to the programmer, arranges lunch or dinner meetings, provides the station access to the label’s artists, and helps the station promote and market itself with contests and giveaways. The promoter, who has developed a good relationship can then make the telephone call and ask the programmer to treat his current record project favorably.

If the promoter has no relationship with the radio programmer from a reporting station, it is highly unlikely that telephone calls will ever be returned. Programmers today have too many things to do and little time to listen to promotional pitches from people and companies they don’t know.

First, it is important to understand that promotion by a label is focused on radio stations that program current, new music. Stations airing older music are using record company catalogues as the basis for their entertainment programming. Those albums and their related singles have been around for years, sometimes decades, and there is limited interest on the part of a label to promote them to radio. However, most energy and money is invested by record companies in promoting the newest singles and album projects.

Record promotion to radio by labels typically needs to answer four questions:

1. How does it help us sell records?

2. What does it do for our effort towards developing the artist?

3. What does it do to further develop our agenda and help us market the artist?

4. Does it make sense for the radio station?

If radio stations ask the label promoters for something of value, whatever it is, the first question to the record company becomes, “How does this help me sell copies of the artist’s record?”

The Contest Promotion

One label discussed its relationship with Clear Channel Communications, the broadcast giant which owns over 1,200 radio stations by describing a national contest. A major artist was preparing to release a new album and go out on tour. The label offered Clean Channel stations a contest which would fly two couples to attend the final dress rehearsal before the concert series began. The winners enjoyed the privilege of being an audience of four rather than four in a crowd of 20,000. The cost was minimal to Clear Channel but provided some interest and excitement around the artist by using the collective power of their stations and web sites.

![]() Figure 8.1 The contest promotion

Figure 8.1 The contest promotion

One label says that everything they do with radio stations to promote an artist “has to really pass the smell test.” They require proof that promotional prizes and free concerts by artists are acknowledged on the air as being given by the label. They expect to receive affidavits from the station showing when the announcements were aired and at how much money those announcements were valued. When the payola law was changed in 1960, the burden of disclosure was also placed on the record labels. The major 2005 payola settlements by NY Attorney General Eliot Spitzer mandate this extra care.

As you create a promotional tour for an artist with a new CD, emphasis should be on the most popular radio stations in targeted cities, especially those “reporting” stations that report their airplay charts to major trade magazines. To determine which stations are rated the highest in audience shares, you will find Arbitron’s reported findings at www.radioandrecords.com, as well as through other media outlets. Specific information about the station programmer’s name, address, and telephone number is available through Bacon’s MediaSource.

After a single has been released to radio, nearly everyone at the label tracks its progress. For the promotion staff, the weekly airplay charts and SoundScan data help guide their work. Monitoring tools track the number of downloads of singles on iTunes, Rhapsody, Napster, and similar services to determine if the music is connecting with consumer’s pocketbooks. Some labels also have staff members who monitor the “buzz” on their new music in chat rooms. All of this information helps the label determine whether they have a hit on their hands, whether they should step up the promotional effort, or whether it’s time to cut their losses and pull the project from the market.

The typical business week for record promoters begins either Tuesday or Wednesday. For country promoters, the airplay charts at R&R and Billboard close Monday night; for pop music, the airplay charts close on Tuesday night. The chart closings will show the successes and failures of singles from the previous week and give the promotion team the information they need to allocate their time for the next seven days. With the plan in place, the promotion staff then begins its weekly cycle of contacting radio programmers to build airplay for the label’s products.

One label executive says his regional label promoters are always on the job. The only time he allows a break is when his promotion team members are on vacation. Jobs as regional promoters with some experience can go to work at a starting salary in the range of $70,000 to $80,000, plus expenses. Vice presidents of label promotion for larger labels can easily earn well over $200,000, plus bonuses and other incentives.ii

Record promotion and its regulation by the Federal government began not long after the advent of commercial radio broadcasting. In 1934, Congress created and passed the Communications Act, which restricted radio licensees—the stations themselves—from taking money in exchange for airing certain content unless the broadcast was commercial in nature. However, this early act contained nothing that prohibited disc jockeys (DJs) from taking payments in exchange for airplay. During the big band era of the 1940s, and the rock ‘n’ roll days of the ‘50s, DJs were routinely taking money from record promoters in exchange for the promise to play a record on the air. Disc jockeys during this time often made their own decisions about which records would be included on their programs, and promoters would approach them directly to influence their record choices.

Lawmakers railed against the rampant bribes being given to DJs to play records. In 1960, Congress amended the 1934 act to include a provision that was intended to eliminate illegal bribes to play music, so called payola. Under the revised law, disc jockeys and radio stations were permitted to receive money and gifts to play certain songs, but the amendment placed a requirement that these inducements be disclosed to the public on the air. If this disclosure was not made, it exposed the DJ and management to possible fines and imprisonment (Freed, A., 2005). The change in the law also created the requirement that record labels must report their cash payments and major gifts to the station for airplay. This 1960 amendment continues to guide the radio and records industries today.

Despite the stronger laws against payola, Federal investigators were called upon to investigate scandals within the record promotion business in the 1970s and 1980s. There were no major convictions despite the appearance that money, drugs, and prostitution were being used as leverage by promoters to get radio airplay for recordings (Katunich, L. J., 2002).

Getting a recording on the radio

The consolidation of radio has concentrated some of the music programming decisions into the hands of a few programmers who provide consulting and guidance from the corporate level to programmers at their local stations. In many cases, local programmers have the ability to add songs to their playlists based upon the preferences of the local audiences. Here is how songs are typically added to station’s playlists for those stations that program new music:

1. A record label promoter or an independent promoter hired by the label calls the station music director (MD), or program director (PD) announcing an upcoming release. Radio music directors have “call times.” These are designated times of the week that they will take calls from record promoters. The call times vary by station and are subject to change. For example, an MD may take have call times of Tuesdays and Thursdays, 2:00–4:00 p.m.

2. Leading up to the add date, meaning the day the label is asking that the record be added to the station’s playlist, the promoter will call again touting the positives of the recording and ask that the recording be added.

3. The music director or program director will consider the selling points by the promoter, review the trade magazines for performance of the recording in other cities, consider current research on the local audience and its preferences, look at any guidance provided by their corporate programmers/consultants, and then decide whether to add the song.

4. The PD will look for reaction or response to adding the song. The “buzz factor” for a song will be apparent in the call-out research and call-in requests, as well as through local and national sales figures.

An important component of promoting a recording to radio is the effectiveness of the record company promotion department or the independent promoters hired to get radio airplay. This would appear to be a simple process, but the competition for space on playlists is fierce. Thousands of recordings are sent to radio stations every year, and the rejection rate is high because of the limited number of songs a station can program for its audience. Some of the recordings are rejected from being included on playlists because they are inferior in production quality, some are inappropriate for the station’s format, and many lose their label support if they fail to quickly to become commercial favorites with the radio audience.

However, the marketer’s litmus test for the viability of a recording is to honestly compare it with other songs on the charts of trade magazines. If it is not at least as good as those listed on the current trade magazine charts, then it doesn’t have any chance at all, even if it has a competitive marketing budget.

The scandal of the 1980s was about the practice of labels hiring independent promoters, or “indies” to attain airplay at radio. Fred Dannen, in his book, Hit Men, found that CBS Records was paying $8–10 million per year to indies to secure airplay for their acts. By the mid-80s he says that amount was $60–80 million for all labels combined. We will discuss independent promotion in the next section.

Label record promotion and independent promoters

Most large labels have a promotion department whose sole purpose is to achieve the highest airplay chart position possible. While most consumers assume a number one song is the biggest seller at retail, the number one song on most Billboard and R&R charts actually is the song that has the most airplay on radio. The connection between airplay and sales is well-documented, so a high chart position is critical to the success of a recording and becomes the heart of the work of a record promotion department.

Radio & Records: Nominees for Independent Promotion Firm for 2004:

All That Jazz

The Jesus Garber Company

Jeff McClusky and Associates*

McGathy Promotion

National Music Marketing

*Winner for the past six years

![]() Figure 8.2 R&R indie nominees

Figure 8.2 R&R indie nominees

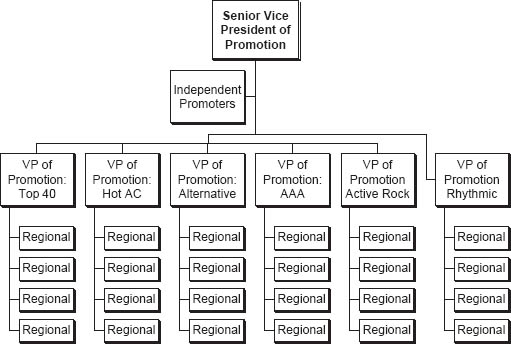

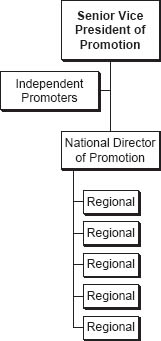

Labels often have a senior vice president of promotion who usually reports directly to the label head. The senior vice president of promotion at a pop music label typically has several vice presidents of various music types based on radio formats. These vice presidents then have regional promotion people who are viewed by the label as field representatives of the promotion department. They are liaisons to key radio stations in their region. The vice president and the so-called regionals are the front line for the label attaining airplay. It is their responsibility to create and nurture relationships with programmers for the purpose of convincing them to add the company’s recordings to their playlists. At a country label, the senior vice president of promotion typically has a national director of promotion and several regionals (see Appendix, p. 159).

Labels sometimes hire independent promoters (indies) to augment their own promotional efforts. Since promoting songs for airplay relies on well-developed relationships, indies may have developed stronger relationships with some key stations than the label has, and the record company is willing to pay indies (half of which is often recoupable from the artist) for the value of those relationships.

Independent promoters have typically made their money this way: they sign an agreement with a radio station to be the stations’ exclusive consultant on new music for a year, and then pay the radio station for that right. The indie promoter does not require the station to play specific songs, according the typical agreement, but the station does promise to give its playlist for the following week to the indie promoter before anyone else. Then, the promoter sends an invoice back to the record company for $3,000 to 4,000 for each single that is charted on stations that they represent. Because of this “exclusive” arrangement with the radio station, record label promotion people have no dealings with the radio stations represented by indies. One label promotion vice president says the $4,000 can easily turn into $30,000 per single if the indie must provide contest prizes to help promote the single at radio and to pay for other promotional expenses. Many arrangements with indie promoters include provisions for bonuses based on their success at charting records with individual stations (Phillips, C., 2002).

Record Promotion at Industry Conventions: A New Revenue Stream for Radio

Clear Channel became the pioneer of the practice of charging record labels to have an exclusive audience with its key programmers. For example, during the annual Country Radio Seminar in Nashville, Clear Channel has required its key 50 country programmers to be present for five 90-minute “showcases” the week of that convention. Labels that reserved one showcase typically presented their newest acts to the programmers and were billed $35,000 by Clear Channel. For the week, the company received $175,000.

![]() Figure 8.3 Record promotion at industry conventions

Figure 8.3 Record promotion at industry conventions

Independent promoters provide the record company a layer of insulation between themselves and radio. The record companies do not deal directly with certain radio stations in matters of adds and spins; rather, they deal only with independent promoters who promote to these stations. As one executive says, “The use of independent promoters creates a clearinghouse by removing the label one step away from…making any compromises that some might make to get a song on the air.” Another says, “This way the money doesn’t go directly from the label to the radio station.”iii

Critics of the independent promotion system claim it had tended to shut-off access to radio airplay by independent labels and artists. Alfred Liggins is CEO of Radio One, a company that owns nearly 70 radio stations targeting African-American audiences. He acknowledges that their exclusive relationships with independent promoters means that labels without an indie promoter are less likely to get a record played on his stations (ABC Television, 20/20, 2002).

The continuing need for independent record promotion to radio stations is changing; however, Lew Dickey, CEO of Cumulus Broadcasting, said in 2003 that his company was “centralizing” their relationships with independent promoters. He did not want indies to “work program directors … and this is really a pet peeve of mine … for things that are untoward, and put young men and women in compromising positions at that age and at that level of experience [who] may not know any better. I think it’s wrong.” Cumulus has since ended its relationships with independent promoters. However, this comment suggests that even new millennium record promotion will always hold the potential to stray into troubling areas for both record labels and radio. The criticism leveled at the practice of independent promotion has caused a large promotion and publicity company to rename its radio promotion services to “radio marketing.”

Record promotion has been a big-dollar investment, which made it a key marketing element necessary to stimulate consumers’ interest in buying new music. Costs for a label to market and promote a single easily reach $1 million, not including the production of the recording or any advances to the artist or producer. Even in the world of country music where annual sales are often less than 10% of all recorded music, labels invest as much as $300,000 just to get the single of a new artist into the top 20 of an airplay chart.

And, according to information developed by the Los Angeles Times, independent promotion has cost record labels an estimated $150 million annually (Phillips, C., 2001).

Clear Channel Communications is among those radio companies that no longer use independent promoters as consultants to its stations. The company instead creates total marketing packages for labels and their artists that can include everything from concert promotion to record promotion. Joining Clear Channel in ending relationships with independent promoters are companies such as Cumulus Media, Enetercom, and others. In 2005, New York Attorney General Eliot Spitzer negotiated multi-million dollar settlements with record labels for alleged violations of payola laws by independent and label promoters, and the FCC began its own investigation of payola violations of radio licensees. While the current trend is away from independent promotion, history has shown that this might just be temporary.

Satellite radio offers the possibility of an expanding horizon for promoting recordings to radio. The services provided by XM and Sirius have a relatively low monthly subscription fee (less than $15), and offer scores of commercial-free music channels. Though the services require that a vehicle must be equipped with a special receiver, many newer cars and trucks have satellite receivers integrated into their standard radios. Satellite radio delivers an audience in the millions, with the size being equivalent to a major market radio station (though the audience is national in scale). Satellite radio offers more sub-genres and niche formats, which gives labels great opportunity for airplay. Record company promoters actively work with satellite music channel programmers seeking adds to their playlists.

Looking toward the possibility of coupling satellite radio with OnStar® Corporation technology, new opportunities may become available to record labels and their promoters. OnStar is a subscription emergency service offered in some vehicles that wirelessly transmits alerts to customer-service agents. Merging satellite and OnStar-type of technologies, consumers will have the opportunity to: hear a song, see who the artist is on the satellite radio faceplate, press OnStar in their vehicle, order the record delivered to their home, and have the CD added to their monthly OnStar bill. Promoters say this is especially attractive for two reasons. First, it satisfies the impulse to buy the CD at a time when the consumer is involved with the music, and second, it tends to provide opportunities for newer artists. Label promoters say that people who adopt new technology are more likely to be the early adopters of new artists.

In Figure 8.5 on the next page is an example of an organizational chart for a typical pop label record promotion department. Note that the VP’s of the various formats are specific to the music. However, the individual regional promoters typically promote all current music types marketed by the label.

![]() Figure 8.4 Promotion department organizational chart for pop music

Figure 8.4 Promotion department organizational chart for pop music

Organizational chart for a typical country label record promotion department:

![]() Figure 8.5 Country label organization chart

Figure 8.5 Country label organization chart

Burnout or burn – The tendency of a song to become less popular after repeated playings.

Indie – A shorthand term meaning an independent record promoter who works for radio stations and record labels under contract.

Payola – The illegal practice of giving and receiving money in exchange for the promise to play certain recordings on the radio without disclosing the arrangement on the air.

Playlist – The weekly listing of songs that are currently being played by a radio station.

Recurrents – Songs that used to be in high rotation at a station, but are now on the way down, reduced to limited spins.

Rotation – Mix or order of music played on a radio station.

Spin – This is a reference to the airing of a recording on a radio station one time. “Spins” refers to the multiple airing of a recording.

Trades – This is a reference to the major music business trade magazines.

Bibliography

ABC Television, 20/20 (November 2002). http://www.abcnewsstore.com/store/index.cfm?fuseaction=customer.product&product__code=T020524%2002).

Ammer, C. (1997). The American Heritage® Dictionary of Idioms, Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

BDS (2005). http://bdsonline.com/submit.html.

Billboard online (2005). http://www.billboard.com/bb/charts/heatseekers.jsp.

cmj.com (2005). http://www.cmj.com/company/.

cmj.com (2005). www.cmj.com/index.

Freed, A. (2005). http://www.historychannel.com/speeches/archive/speech_106.html.

hipnotikent (2004). http://hipnotikent.com/industryTips/bds.htm.

Hull, G. (2004). The Recording Industry, London: Routledge, pp. 201–202.

Katunich, L. J. (April 29, 2002). Time to Quit Paying the Payola Piper, Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Review.

Nielsen SoundScan (2005). aud.soundscan.com.

Phillips, C. (May 24, 2002). Congress Members Urge Investigation of Radio Payola, LA Times.

Phillips, C. (May 29, 2001). Logs Link Payments with Radio Airplay, LA Times.

radio-media (2005). http://www.radio-media.com/song-album/articles/airplay26.html.

Soundsource (2005). http://soundsource.ca/broadcastservices.asp?subsection=24.

wikipedia.org (2005). http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Billboard_magazine#History.

______________________

i Lon Helton of Radio & Record, personal interview.

ii Personal interviews, Fall 2004.

iii Personal interviews, Fall 2004.