| 20 | The Recording Industry of the Future |

The record label of the future is expected to be very different from what is in place today. The current business model is structured around music as a physical product, sold through brick-and-mortar retail outlets. The record label of the future may be shifting away from that of product provider, to more of a service provider, much like television networks are today. Their role may be limited to developing content, and then marketing that content to consumers. This represents a drastic paradigm shift for record labels that have resisted moving into the digital age.

Before unraveling the mystery of the future of recorded music, we must first examine the basic principle behind recorded music and how it is consumed. Then we must examine how, through the course of time, new innovative methods replace old methods of accomplishing this task. Recorded music allows the consumer to possess a captured musical performance, and replay that performance whenever and wherever desired. The music business for the past 100 years has been supplying that to consumers in the form of a physical product. But many things have changed, especially in the fields of entertainment and communication. To understand the future, we must move away from the concept of supplying consumers with a physical product. After all, the goal is for the consumer to replay the recording at will, and modern technology does not mandate that it must be in a physical form. Instead, we should look at the record business as music delivery systems, since the goal is to get the consumer to pay for the convenience of listening to their favorite music on demand.

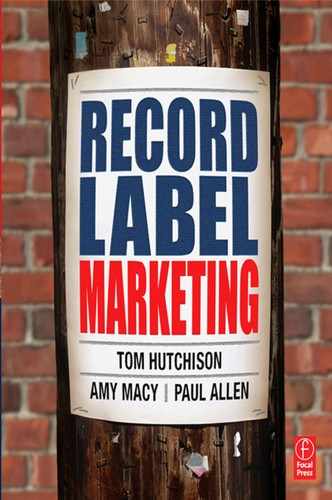

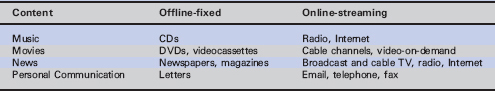

The new model for record labels as service providers involves a drastic overhaul of the label system. The following chart illustrates how within the past 100 years, with the exception of radio, all new music delivery systems have followed the same basic format of creating a physical product. The one exception, radio, is not an on-demand system capable of being user-controlled; and at this point, radio does not provide direct income for the labels.

Table 20.1 Communication flow

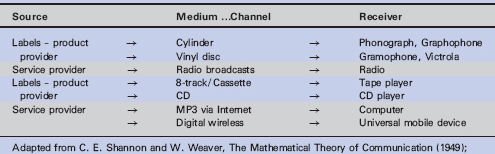

Changes in music delivery systems have at times driven changes in record label ownership and partnerships. When radio was first developed in the 1930s, radio networks sought to own record labels. RCA, with its NBC Radio Network, purchased Victor records in 1929, and CBS purchased Columbia and Okeh Records in 1938 (Sony website, 2005). In the 1970s through the 1980s, entertainment hardware companies sought alignment with labels. Philips electronics created PolyGram Records in 1972 (Hoover’s, 2005), and Thorn Electrical Industries purchased EMI in 1979. Sony purchased CBS records in 1988, and Matsushita bought MCA Records in 1990. This alignment started to change in the 1990s when telecom and utility companies took an interest in record labels. Vivendi bought Universal in 2000, and AOL merged with Time Warner (parent to the Warner Label Group) in 2001. Bertelsmann AG, parent company to RCA and BMG, ventured into the broadcast media industry (PBS, 2002). These mergers and relationships were designed to create synergy, defined as a mutually advantageous conjunction or compatibility of distinct business participants or elements (as resources or efforts) (Merriam-Webster Online, 2005). Synergy allows for a company to use one branch to support the activities of another branch. Disney is an example of a company that has used synergy to create a “superbrand” of some of their assets using a collaborative effort among their film, animation, music, theme park and product merchandising branches to push a brand into the marketplace. In the 1980s, MCA President Irving Azoff managed to use Universal’s film division to propel his artists’ careers (Dannen, F., 1991). BMG has the potential to use their magazine and television affiliates to promote an artist.

Under the old label/receiver relationship model, electronics companies sought to promote new consumer entertainment hardware through the acquisition of music and movie catalogues. After Sony lost the format debate on VCRsi, they pursued the purchase of CBS Records, and Columbia and Tri-Star Pictures. The idea was that they could then provide pre-recorded software in a format that supported their new hardware. The Sony MiniDisc is an example. Sony attempted to make the MiniDisc into the next recorded music platform by releasing pre-recorded titles from the CBS catalog. At one time, five of the six major labels were affiliated with electronic hardware companies.

Table 20.2 The label/receiver relationship model

As the promise of digital delivery of movies and music loomed, companies began to realign themselves in partnerships involving content (source) and service providers (channels). The expectation was that the synergy created by aligning record companies with online and cable service providers would attract customers and increase sales. America Online merged with Time Warner, gaining access to vast amounts of content to fill the AOL “channel.” Bertelsmann AG, parent company to RCA and Arista, began to increase its presence in the European media landscape (Frontline: Merchants of Cool, 2001). Vivendi purchased Universal in 2000 combining “Vivendi’s telecommunications assets with Seagram’s film, television and music holdings (including Universal Studios) and Canalþ’s programming and broadcast capacity” (Frontline: Merchants of Cool, 2001). Universal had previously purchased Polygram under the leadership of Edgar Bronfman, Jr.

Table 20.3 The label/channel relationship model

But as of 2005, these companies have yet to capitalize on the synergy they hoped to create. The labels and other divisions of these media giants have been criticized as being too entrenched in their business practices to open up to innovative synergistic opportunities. AOL has divested itself of Warner Music Group, rumors have been flying about Vivendi parting with Universal, and BMG and Sony Music Entertainment have further consolidated the industry by creating a joint venture involving just the label operations and distribution.

The study of new media, including the recording industry, requires an understanding of what constitutes new media and how it affects the future of music delivery. To understand how media is evolving, it is necessary to look back at earlier technology waves and apply them to the context of diffusion theory. We have previously discussed the evolution of fixed-music formats, noting that radio is the only historical innovation to deliver music in a format other than physical product. But the future holds more promise in the area of providing music as a service rather than a product, especially one that generates revenue for the record labels.

The development of online services

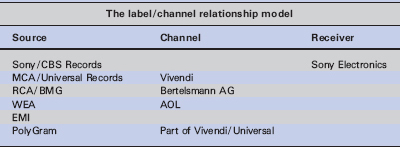

The telephone can be considered the first streaming communication device to proliferate into U.S. households throughout the twentieth century. The public utility business structure made it possible to supply most households with a telephone line at a reasonable cost, and adoption became widespread. The basic limitation of the twentieth century telephone line was limited bandwidth. Bandwidth can be described as the capacity, or the maximum data transfer rate of an electronic communications system. The telephone line is limited and restrictive. When community antenna television (CATV) became popular in the 1970s and 80s, it became necessary to install an additional cable in the home—a coaxial cable (a transmission line of high bandwidth television signals that consists of a tube of electrically conducting material surrounding a central conductor held in place by insulators). The problem with initial coaxial cables from the CATV providers was that the cable only allowed for one-way communication; it was not interactive. Interactivity is described as a two-way interaction between sender and receiver. While the standard telephone line is interactive, it is not capable of rapid multimedia transmission.

By the 1980s, homes were wired with one cable and one telephone line, each for separate tasks. However, recent advances in both areas have caused some convergence of media in the home: interactive cable and broadband telephone lines. This convergence brings a higher level of service into the home, but telecom and cable companies have been wrangling over who will be allowed to provide what services. This may have actually delayed the onset of comprehensive media and communication services.

Table 20.4 Phone lines vs. Cable

We receive our entertainment and information through two types of channels: offline and online. Online is considered any type of transmission that is streaming in real time, and includes airwaves and wireless communication transmission (radio and cell phones). We also receive information and entertainment through fixed-media such as CDs, videocassettes, DVDs, and newspapers. Under those circumstances, we are considered offline. Reception of offline content often requires some physical product, and the inconvenience of driving to the video rental store or music store, or ordering through the mail. The fixed-media content business has been allowed to thrive mainly because the streaming media infrastructure was not in place to provide the same media products at a reasonable cost and convenience (of both hardware and service) to the consumer.

Table 20.5 Fixed vs. streaming media

Technology diffusion and convergence

The new media model accounts for a proliferation of new technology devices at a reasonable cost to the consumer. Under this model, a variety of services are offered to consumers as various submarkets begin to embrace the new delivery methods. Predicting who will adopt what is a challenge for marketers, but diffusion theory can offer some guidance. The rate of diffusion is positively related to the standardization and simplicity of use. The new technological devices that offer consumers the opportunity to listen to music more conveniently and with less cost may prevail. Some of the issues that may affect adoption are shown in Table 20.6.

Table 20.6 Attributes of new media

Digital rights management (DRM) is a systematic approach to copyright protection for digital media, designed to prevent illegal distribution of paid content over the Internet. This was developed in response to the rapid increase in online piracy of commercially marketed material, which proliferated through the widespread use of peer-to-peer file exchange programs. Most DRM programs require the user to register or verify online before transferring the protected music to a portable device. This two-edged sword has offered some security to record labels, but has frustrated consumers and discouraged the adoption of digital downloads. Rob Enderle of TechNewsWorld comments: “I, like many others, see DRM as a pain. I just don’t want to deal with it. So I’ve gone back to ordering CDs from Amazon.com, ripping the CDs into MusicMatch, and then putting the music anyplace I want—in my home, on my person or in my car—without violating the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA)” (Enderle, R., 2004).

Technology convergence: the universal mobile device

Convergence of technology is appearing in many forms today. Cable TV has incorporated high-speed Internet access; computers have become music management devices; the television and stereo system have now become an integrated media system; the laptop computer doubles as a DVD player. Convergence exists when two or more separate entities combine to form one.

At some point, consumers draw the line at carrying around an MP3 player, cell phone, portable video game and a digital camera. Enter the 3G handset technology, developed by cell phone manufacturers. This third generation (3G)cell phone technology incorporates text and video messaging, music downloads, games, and mobile TV into one handset and offers a new outlet for the music industry. This music-to-mobile (M2M) market was first developed through the offering of “ringtones.” Consumers can purchase and download these pieces of music to their cell phones to “personalize” their ring. Original ringtones were a series of beeps or sounds, rather than an actual recording. Record labels were not the beneficiary of licensing for these early ringtones, only music publishers. The more recent “ringtunes,” or master recording ringtones use an actual piece of the recording, and thus generate a royalty for the label and the artist. Similarly, ring back services allow telephone owners to customize the sound a caller hears before the owner answers the call by replacing the traditional “ring-ring” sound with actual recordings or other sounds. According to the IFPI, music-to-mobile is already big business in Japan, South Korea and Taiwan. In South Korea, music-to-mobile services generated $29 million for record companies in 2003, a full 18% of the total music market.

This represents a potential new market for the sale of recordings. In March 2004, Variety reported that more than 1.3 billion people have mobile phones—exceeding the combined number of PCs and televisions (McCartney, N., 2003). This is predicted to reach 2 billion by 2008; yet more recent predictions from Deloitte and Touche place the 2 billion milestone at the end of 2005 (Reuters News Service, 2005). Kusek and Leonhard, in their book, The Future of Music:A Manifesto for the Digital Music Revolution, state that if all cell phone users around the world paid just $1 per month for access to music, it would amount to half of the current value of annual worldwide recorded music sales. And the mobile phone market is growing faster than any previous technological innovation. The potential of M2M offers enormous opportunities to grow the market for recorded music. China and the U.S. are regarded by the IFPI as the best markets for potential growth of M2M; China because of its large population, increasing disposable income and vast young consumer base; the U.S. because it is the largest market for recorded music sales, and 3G networks are currently being implemented.

The 3G networks have the capacity to deliver a multitude of content to mobile devices, but music delivery may become the driving force in the adoption of these systems by younger users. BBC commentator Bill Thompson remarks, “just as the World Wide Web was the ‘killer application’ that drove Internet adoption, music videos are going to drive 3G adoption … Why should I want to carry 60 GB of music and pictures around with me in my pocket when I can simply listen to anything I want, whenever I want, streamed to my phone?” (Thompson, B., 2004).

New markets: what does the consumer want?

Kusek and Leonhard state: “Music wants to be mobile.” They point to the overwhelming success of the Sony Walkman. They also point out that today’s teenagers have grown up in an era of technology access with the cell phone and the Internet. Today’s kids, whom they call screenagers, are active users of video games, cell phones, instant messaging, email, surfing the web, and controlling and manipulating their own music collection. Much like the generations before them, the Net Generation is interested in sharing their music interests with peers—only with today’s technology, it has become much easier and at the expense of the record labels. But these consumers don’t just pass around free and illegal music files. They also visit artist websites,listen to online radio, attend concerts and discuss music with their friends. They are active music consumers, if not paying customers of the record business. The potential to actually sell music to these consumers is great, but only on their terms. Young consumers do not like being required to purchase a complete album of songs when they just want one or two singles. When asked in focus groups, they will often comment that $15-$20 is too much to pay just to get the one or two songs they want.

The success of Napster in 2000, and of subsequent peer-to-peer (P2P) file-sharing services, proved that the consumer was ready and eager to embrace downloading digital music. The IFPI states that the key drivers of the M2M market are consumer demand and technology. Of course pricing factors in also. Young consumers like to personalize their handset and are willing to pay premium prices for ringtones. Content owners, network operators and handset manufacturers all consider music as a motivating force in attracting new customers and driving repeat purchases. Consumer research by Nokia found that music surpassed other forms of entertainment and content in popularity.

![]() Figure 20.1 3G Handsets (Source: Sony Ericsson)

Figure 20.1 3G Handsets (Source: Sony Ericsson)

Table 20.7 Consumer interest in 3G uses |

|

Content |

Consumer interest |

Music |

65% |

Film |

54% |

Games |

44% |

Sports |

40% |

Increased penetration of 3G devices is necessary for the growth of M2M. Increased storage capacity of portable devices is necessary for music collections. In 2005, Sony-Ericsson announced plans to introduce a music-player mobile handset marketed under the Walkman brand, and Nokia setup a partnership with Microsoft to allow users to download tracks to their handsets and then transfer them to a computer for CD burning. Improved visual screen technology or head-mounted displays may drive the film and music video adoption, but it is anticipated that users will only be interested in short video features, not 30 or 60 minute programs. This makes the music video an ideal format to drive sales of 3G technology.

The desire to own physical product may still exist, with consumers continuing to collect and possess the music that they value most. Consumers may begin to prioritize music based on their subjective value of the music: (1) music that they love and wish to own, and add to their collection, (2) music they like and are willing to pay to listen to, and (3) music that they are willing to listen to at no cost. This could create a tiered system of music consumption among customers and could sustain sales of physical units. The market for Internet-based digital music services will continue to grow, but subscription-based systems will only take off when the consumer can access music remotely through portable devices.

As delivery systems change, the record industry may need to reinvent itself as a service provider, rather than a product provider. Music is moving from an off-line product-based commodity to an online commodity, and ultimately to an online service. Record labels may have to find income sources from licensing for streaming and music downloads. Licensing by record labels to third-party subscription-based digital music services is necessary for the label industry to survive in the digital economy. Digital rights management will need to evolve to a transparent system that does not impede on the consumer’s right to create personal copies. Starbucks has already initiated a music downloading system that provides adequate copyright protection for providers without DRM systems. Starbuck’s customers can use their laptops and the venue’s wi-fi system to create custom CDs devoid of DRM.

Presently, the limitation is in the offerings. Many labels have yet to license their entire catalog for digital downloads and are still reluctant to do so. Kusek and Leonhard believe that statutory compulsory licensing will be necessary to provide what they describe as a ubiquitous presence of recorded music. What would bring ultimate copyright protection and satisfy consumer desires to copy and share music would be widespread adoption of subscription-based services. But until more content is licensed and made available, consumers may remain reluctant to embrace subscription-based services with limited offerings. With a broad consumer base all subscribing to the same service, copy protection would become unnecessary as all consumers would have access to—and be paying for—their favorite music. Consumers could share music with one another, provided they are all “paying members.” Personal music collections could become unnecessary under the celestial jukebox model. Music downloading service Rhapsody describes the celestial jukebox as “immediate access to more music than you ever imagined. Thousands of albums by top artists, bands, and composers—all in CD-quality sound and delivered to you effortlessly via the Internet [or digital mobile devices]” (listen.com, 2005).

It is expected that music markets will continue to fragment, especially with new forms of music distribution. This means that promoting music through mass media will become only one of many ways to market and promote new music. Because there is so much music in the marketplace, consumers have traditionally relied on gatekeepers and tastemakers to guide them in their music choices. Radio playlists serve to reduce the plethora of musical offerings to just the most popular songs. Kusek and Leonhard state:

“Most consumers want and need tastemakers or taste-agents … that package programs and expose us to new music. This is why word-of-mouth marketing works so well … A friend is a true tastemaker.”

Music placement in videos, movies, video games, and commercials is on the rise and will become even more popular as a way to introduce consumers to music. Direct marketing is becoming more prevalent with the use of the Internet. And marketing to fans, through online fan clubs, is also on the rise, producing a word-of-mouth phenomenon. As consumers begin to rely less on mass appeal products such as Top 40 radio and MTV, they will need guidance to wade through the overabundance of recorded music to find what they like. But new marketing models may be developed that rely more on a pull strategy (the consumer seeking information) than a push strategy (the consumer being bombarded with information). As consumers seek out new music to their liking, collaborative filtering software will help consumers find what they like by developing individual taste profiles.

Collaborative filtering software examines a user’s past preferences and compares them with other users who have similar interests. When that user’s interests are found to match another group of users, the system starts making suggestions of other things this group likes (Weekly, D. E., 2005). Suppose you normally never listened to jazz music, but you liked artists A, B, and C a lot. If numerous other people who don’t normally listen to jazz also like A, B, and C, but also like band D, the system might suggest D to you and be relatively confident that you’ll like it. Amazon.com uses the technology to recommend other products with their “people who bought this product also purchased these other products.” Such marketing is less intrusive and most importantly, more intuitive. Consumers are reluctant to pay attention to messages that are not tailored to them—advertising that is general in nature and doesn’t understand their individual preferences. However, the more intuitive recommendation engines are highly likely to suggest products that the consumer actually likes, therefore, becoming the ultimate in niche marketing, where each niche consists of one person and their individual taste profile. Customers are less likely to ignore marketing that is precisely targeted to their interests.

We are likely to see more alignment of music labels with digital wireless providers in the future, much like the previous relationships with hardware companies. New music delivery methods have the potential to reinvigorate the struggling recording industry; but in order for the new music model to work, these systems must be simple, affordable, available, compatible, convenient, and valuable.

3G – Third-generation cell phone handsets and systems capable of transmitting, storing and playing multimedia content.

Bandwidth – The capacity or the maximum data transfer rate of an electronic communications system.

Coaxial cable – A transmission line of high bandwidth television signals that consists of a tube of electrically conducting material surrounding a central conductor held in place by insulators.

Collaborative filtering software – Examines a user’s past preferences and compares them with other users who have similar interests.

Convergence – Moving toward union or uniformity.

Digital rights management (DRM) – A systematic approach to copyright protection for digital media, designed to prevent illegal distribution of paid content over the Internet.

IM – Instant text messaging by the user of a computer or wireless device.

Music-to-mobile (M2M) – Offering the ability to download music to wireless portable devices using cell phone, wi-fi or satellite technology.

Online – Any type of transmission that is streaming in real time, including airwaves and wireless communication transmission (radio and cell phones).

Ringtones – A tune composed of individual sequential or polyphonic beeps based on an existing song.

Ringtunes – or master recording ringtone. A ringtone that uses an actual sound recording by the original artist.

Tastemakers – Opinion leaders whose personal tastes in music, movies or other popular culture items influences others.

Wi-Fi (short for wireless fidelity”) – A term for certain types of wireless local area networks.

Bibliography

Dannen, F. (1991). Hit Men, Vintage. (0679730613).

Enderle, R. (2004). Starbucks and HP: The Future of Digital Music, Ecommerce Times. http://www.ecommercetimes.com/story/33164.html.

Frontline: Merchants of Cool (2001). http://www.pbs.org./wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/cool/giants/bertelsmann.html. Frontline: Merchants of Cool (2001). http://www.pbs.org./wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/

Frontline: Merchants of Cool (2001). http://www.pbs.org./wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/cool/giants/vivendi.html.

Hoover’s (2005). Philips Electronics. Hoover’s Company Profiles.

listen.com (2005). http://www.listen.com/rhapabout.jsp?sect=juke.

McCartney, N. (03/29/03). Cellphone Media Making Noise, Variety.com.

Merriam-Webster Online (2005). http://www.m-w.com/cgi-bin/dictionary?book=Dictionary&va=synergy&x=23&y=17

PBS (2002). http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/cool/giants/bertelsmann.html.

Reuters News Service (01/18/05). Cell Phone Market Seen Soaring in ‘05. Reuters News Service.

Sony website (2005). http://www.sonymusic.co.uk/uk/history.php.

Thompson, B. (11/22/04). Music Future for Phones. http://news.bbc.co.ukBBC News/go/pr/fr/-/1/hi/technology/4032615.stm.

Weekly, D. E. (02/08/05). http://david.weekly.org/writings/collab.php3.

______________________

iSony introduced the Betamax format for VCRs but ultimately lost out to the more popular VHS format of its competitors.