| 12 | The Music Retail Environment |

Marketing and the music retail environment

The four P’s of product, promotion, price, and placement converge within the music retail environment—this being the last stop prior to music being purchased. This environment is designed to aid consumers in making their purchasing decision. This decision can be influenced in a number of ways, depending on the consumer. For example, “Does the store have hard-to-find releases?”; “Do they have the lowest prices?”; “Is it easy for consumers to find what they’re looking for?”; “Does the store have good customer service and knowledgeable employees?” These questions should be answered, in one way or another, within the confines of the retail environment through the use of the four P’s.

To assist music retailers in determining business strategies, companies look for current sales trends as well as educational and support networks. The National Association of Recording Merchandisers (NARM) is an organization conceived to be a central communicator of core business issues for the music retailing industry.

Founded in 1958, NARM is an industry trade group that serves the music retailing community in the areas of networking, advocacy, information, education and promotion. Members include brick-and-mortar, online and “click-and-mortar” retailers, wholesalers, distributors, content suppliers (primarily music labels, but also video and video game suppliers), suppliers of related products and services, artist managers, consultants, marketers, and educators in the music business field.

Retail members, who operate 7,000 storefronts that account for almost 85% of the music sold in the $12 billion U.S. music market, represent the big national and regional chains—from Anderson (Wal-Mart wholesaler), Best Buy, Borders, Circuit City, Handleman (Wal-Mart and Kmart wholesaler), Hastings Entertainment, Musicland, Newbury Comics, Target, Tower, TransWorld (FYE), Virgin—to the small, but influential “tastemaker” independent specialty stores. Additional members also include online retailers such as Amazon.com, eBay and iTunes.

Distributor and supplier members account for almost 90% of the music produced for the U.S. marketplace. This includes the four major music companies: Sony BMG, EMI, Universal Music and Video, and WEA, and many of the labels they represent. A few of the label members are Atlantic, Blue Note, Capitol, Capitol-Nashville, Columbia, Curb Records, DreamWorks Records, Elektra Entertainment, Epic Records, Geffen Records, Hollywood Records, Interscope Records, The Island Def Jam Music Group, J Records, Jive Records, Maverick, Mercury/MCA Nashville/Lost Highway, RCA Label Group, RCA Music Group, RCA Victor Group, Rhino, Sony Classical, Verve Music Group, Walt Disney Records, Warner Bros., Welk Music Group and Wind-up Records. This list extends even further to include influential independent labels and distributors. For more information regarding NARM and activities, visit www.narm.com.

The four P’s are applicable as an outline for retailer considerations in doing business:

How does a retailer learn about new releases? Distribution companies are basically extensions of the labels that they represent. To sell music well, a distribution company needs to be armed with key selling points. This critical information is usually outlined in the marketing plan that is created at the record label level. Record labels spend much time “educating” their distributors about their new releases so that they can sell and distribute their records effectively.

Distribution companies set up meetings with their accounts, meaning the retailers. At the retailer’s office, the distribution company shares with the buyer—that is the person in charge of purchasing product for the retail company—the new releases for a specific release date, as well as the marketing strategies and events that will enhance consumer awareness and create sales. Depending on the size of the retailer, buyers are usually categorized by genre or product type, such as the R&B/hip-hop buyers, or the soundtrack buyer.

Purchasing music for the store

When making a purchase of product, the buyer will take into consideration several key marketing elements: radio airplay, media exposure, touring, crossmerchandising events, and most critical, previous sales history of an artist within the retailers’ environment; or if a new artist, current trends within the genre and/or other similar artists. On occasion, the record label representative will accompany the distribution company sales rep with the hopes of enhancing the knowledge of the buyer of the new release. The ultimate goal is to increase the purchasing decision, while creating marketing events inside the retailer’s environment.

Most record labels, along with their distributors, have agreed on a forecast for a specific release. This forecast, or number of records predicted to sell, is based on similar components that retail buyers consider when purchasing product. Many labels use the following benchmarks when determining forecast:

Initial orders or I.O.—This number is the initial shipment of music that will be on retailers’ shelves or in their inventory at release date.

90-day forecast—Most releases sell the majority of their records within the first 90 days.

Lifetime—Depending on the release, some companies look to this number as when the fiscal year of the release ends, and the release will then rollover into a catalog title. But on occasion, a hit release will predicate that forecasting for that title continues, since sales are still brisk.

Inventory management

Larger music retailers have very sophisticated purchasing programs that profile their stores’ sales strengths. Using the forecast, as well as an overall percentage of business specific to the label or genre, the retailer will determine how many units it believes it can sell. This decision is based on historical data of the artist and/or trends of the genre along with the other marketing components.

Keeping track of each release, along with the other products being sold within a store is called inventory management. Using point-of-sale (POS) data, the store’s computer notes when a unit is sold using the Universal Product Code (UPC) bar code. Depending on the inventory management system, a store may have ten units on-hand, which is considered the ideal maximum number the store should carry. The ideal minimum number may be four units. If the store sells seven units, and drops below the ideal inventory number of four as set in the computer, the store’s inventory management system will automatically generate a re-order for that title, up to the maximum number. This min/max inventory management system may then download the re-order through an electronic data interchange (EDI) to its supplier, and the product is then shipped to the retailer within a few days. To avoid waiting for the product to arrive, a retailer may opt to drop-ship product directly from the distribution company, avoiding the delay of processing at either the headquarters’ distribution center (DC) or the one-stop supplier.

Turns and returns

Know that a store’s success is based on the number of units it sells within a fiscal year. Clearly, the size of the store dictates how much product or inventory it can hold. On average, a 2,500 square-foot store may hold 20,000 units. According to NARM 2002 data, the average annual inventory turn for music is 4.4 times. As an industry standard, this store would sell: 20,000 units × 4.4 turns = 88,000 units in a fiscal year. This does not mean that every title sells 4.4 times, but rather the store averages 4.4 sales per year for every unit it is holding.

To manage the real estate within the store, the best-selling product should receive the most space. To keep a store performing well, the inventory management system should notice when certain titles are not selling. Music retailers have an advantage over traditional retailers in that if a product is not selling, they can send it back for a refund, called a return. The refund is usually in the form of a credit, and the amount credited is based on when the product is returned along with other considerations such as if a discount had been received. According to NARM 2002 data, the industry return average is 19.5% for music. To put this statistic another way, for every 100 records in the marketplace, nearly 20 units are returned to the distributor.

According to the National Security Retail Survey of 2002, the average retailer loses about 1.7% of product to shrinkage—or shoplifting. Other research notes that the music retailer can lose between 4–4.5% in product. But in any outlet, nearly 50% of the missing product is due to employee theft.

What do music retailers do to protect against shrinkage? Regarding employees, retailers use many screening techniques such as past employment records, criminal checks, multiple interviews and personal reference checks. As for consumers, there are various techniques to help protect against shoplifting. Loss prevention staff is also employed by many retailers.

Since thieves need privacy, training employees to serve the customer has a dualpurpose: To help secure a sale, and to let the would-be thief know that the “store” is watching. Reducing clutter and sighting blind spots help keep visibility high. The use of uniformed and plain-clothed detectives is common in larger format stores, with good results; but the use of technology has been a big aid in dissuading the shoplifter. Source tagging is the use of embedded security devices placed within the CD packaging. With the use of electronic article surveillance (EAS), stores place security panels at the exit. As a product is sold, the source-tag is deactivated. If a product that has not been purchased moves through these security panels, a warning siren occurs, notifying store personnel of the potential shoplifting event.

Survey after survey indicates that music consumers find out about new music primarily via the radio. So it would seem that music retailers would use radio as their primary advertising vehicle to promote their stores and product. But they do not. Cost considerations including reach and frequency of ads have caused music retailers to choose print advertising as their primary promotional activity. Consumers have been trained to look in Sunday circulars for sales and featured products on most any item. Major music retailers now use this advertising source as a way to announce new releases that are to street on the following Tuesday, along with other featured titles and sale product.

Once inside the store, promotional efforts to highlight different releases should aid consumers in purchasing decisions. These marketing devices often set the tone and culture of the store’s environment. Whether it is listening stations near a coffee bar outlet, or oodles of posters hanging hodge-podge on the wall, a brief encounter within the store’s confines will quickly identify the music that the store probably sells.

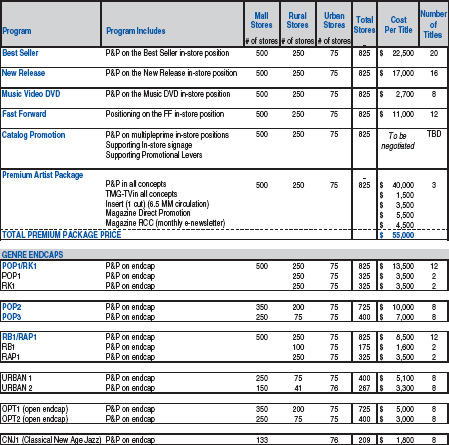

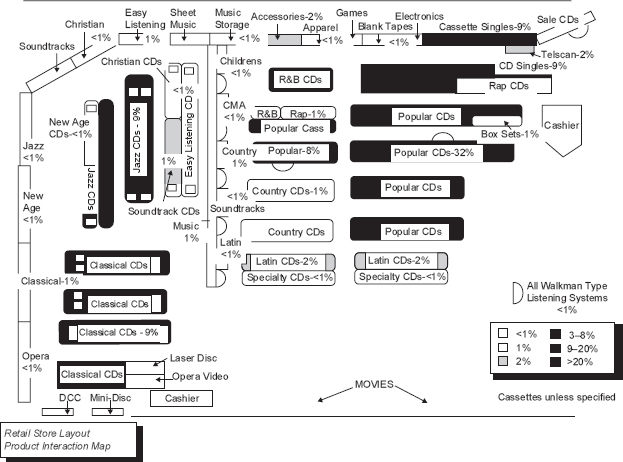

Featured titles within many retail environments are often dictated from the central buying office. As mentioned earlier, labels want and often do create marketing events that feature a specific title. This is coordinated via the retailer through an advertising vehicle called cooperative advertising. Co-op advertising, as it is known, is usually the exchange of money from the label to the retailer, so that a particular release will be featured. Following are examples of co-op advertising:

Pricing and positioning (P&P)—P&P is when a title is sale-priced and placed in a prominent area within the store.

End caps—Usually themed, this area is designated at the end of a row and features titles of a similar genre or idea.

Listening stations—Depending on the store, some releases are placed in an automatic digital feedback system where consumers can listen to almost any title within the store. Other listening stations may be less sophisticated, and may be as simple as using a free-standing CD player in a designated area. But all play back devices are giving consumers a chance to “test drive” the music before they buy it.

Point-of-purchase (POP) materials—Although many stores will say that they can use POP, including posters, flats, stand-ups, and so on, some retailers have advertising programs where labels can be guaranteed the use of such materials for a specific release.

Print advertising—A primary advertising vehicle, a label can secure a “mini” spot in a retailer’s ad (a small picture of the CD cover art), which usually comes with sale pricing and featured positioning (P&P) in-store.

In-store event—Event marketing is a powerful tool in selling records. Creating an event where a hot artist is in-store and signing autographs of his or her newest release guarantees sales, while nurturing a strong relationship with the retailer.

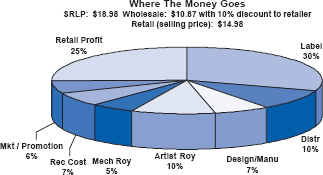

The following grid is a sample forecasting and P&P planning tool used to predict I.O. and initial marketing campaign activities within a retailer’s environment.

Rack jobbers such as Anderson and Handleman purchase nearly 30% of overall music. They supply music to mass merchants such as Wal-Mart and Kmart.

Alliance is the largest one-stop, whose primary business is supplying music to independent music stores.

Figures are based on a major distributor’s overall business with these actual accounts. Note that ten accounts purchase nearly 80% of all records, which makes them very important in the marketing process. For Target to not purchase a title would mean that over 10% of sales would be lost, based on these numbers. This does not mean that a record would sell 10% less over the lifetime of the release, but it does mean that consumers will have to find that title in another store other than Target.

![]() Figure 12.1 Sales forecasting grid

Figure 12.1 Sales forecasting grid

![]() Figure 12.2 Sample retail chain P&P costs and programs

Figure 12.2 Sample retail chain P&P costs and programs

![]() Figure 12.3 Sample Rack Jobber P&P program and costs

Figure 12.3 Sample Rack Jobber P&P program and costs

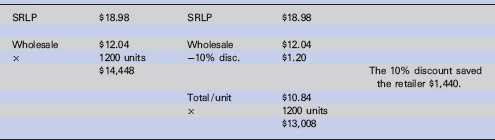

Although record labels set the suggested retail list price (SRLP) for a release, this is not what retailers are required to sell the product for. Most often, the SRLP sets the wholesale price or the cost to the retailer. In negotiating the order, the retailer may ask for a discount off the wholesale price. The retailer may also ask for additional dating, meaning that the retailer is asking for an extension on the payment due date. Each distributor has parameters in which this transaction may occur.

Generally, music product comes in box lots of 30 units. A retailer will receive a better price on product if it purchases in box lots. For example, a retailer wants to purchase 1,200 units of a new release with a 10% discount and 30 days dating. See Table 12.1.

Table 12.1 Box lot discount

Normally, the money due for this purchase would be received at the end of the following month that the record was released. However, with an extra 30 days dating, the due date is extended, giving the retailer a longer timeframe in which to sell all the product. Adding extra dating is often a tactic of record labels that want retailers to take a chance on a new artist that may be slower to develop in the marketplace.

The price of product reflects the store’s marketing strategy. The major electronic superstores look to music product as the magnet to get customers through their doors, which is why music prices in these environments are often lower than anywhere else. Often, these stores will sell music for less than they purchased it, called loss-leader pricing. But these stores will also raise the price after a short period of time, usually within first two weeks after the street date.

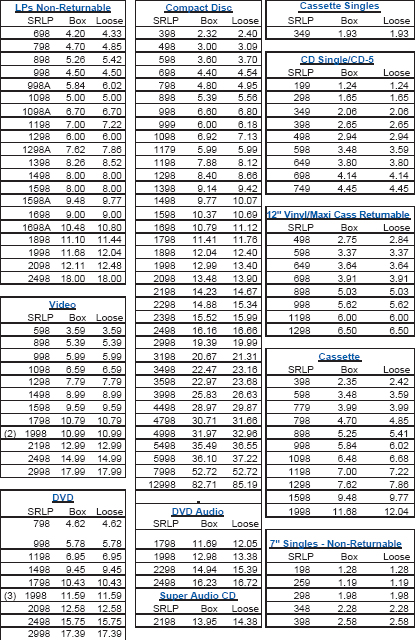

![]() Figure 12.4 Sample distribution pricing schedule

Figure 12.4 Sample distribution pricing schedule

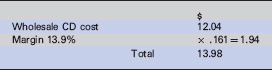

Margin and markup are both calculated using the wholesale purchase price of the product. Percent margin uses the selling price as the denominator, whereas percent markup uses the purchasing (wholesale) price as the denominator for calculating.

Margin percentage on product is determined with the following calculation:

![]()

If an SRLP CD of $18.98 is purchased wholesale for $12.04 and the store wants to sell it for $13.98, the margin percentage is $13.98 – $12.04/$13.98 = 13.9%.

Although there are variable ways to calculate margin, most stores use this retail markup calculation since it takes into consideration differing price lines, product extensions and customer demands in retail value.

Markup uses a similar calculation, but divides the dollar markup by the wholesale cost.

![]()

If an SRLP CD of $18.98 is purchased wholesale for $12.04 and the store wants to sell it for $13.98, the markup percentage is $13.98 – $12.04/$12.04 = 16.1%

There is always an arithmetical relationship between gross margin and markup.

A gross margin of 40% requires a markup of 66.67% calculated as 40 ÷ (100 – 40).

A gross margin of 60% requires a markup of 150% calculated as 60 ÷ (100 – 60).

To achieve a target gross margin of 13.9% on the previous example, based on the purchase cost, the calculations are as follows:

A gross margin of 13.9% requires a markup of 16.1% calculated as 13.9 ÷ (100 – 13.9) – 16.1%.

When setting prices, retailers think about markup since they start with costs and work upwards. When thinking about profitability, retailers think about margin, since these are the funds leftover to cover expenses as well as account for profit. Importantly, negotiating for the best discount off the wholesale price improves both markup and margin.

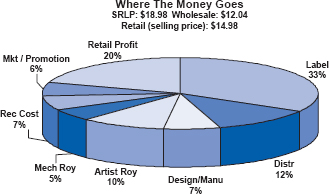

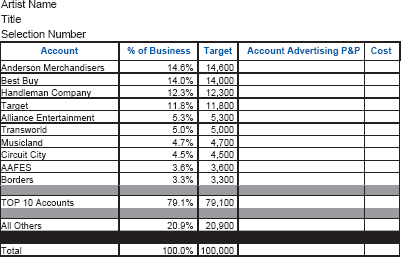

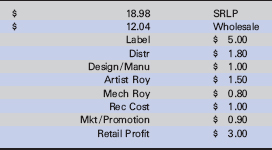

Where the money goes

When the consumer plunks down their money at the cash register to purchase a CD, Figure 12.5 shows how that money is divided between all the invested parties.

![]() Figure 12.5 Where the money goes

Figure 12.5 Where the money goes

If the retailer receives a 10% discount off the wholesale price, then the label gets a reduction of 3% and the distributor a reduction of 2%, while the retailer enjoys a 25% increase in margin, from 20% of retail price to 25%, as shown in Figure 12.6.

![]() Figure 12.6 Where the money goes with 10% discount to retailer

Figure 12.6 Where the money goes with 10% discount to retailer

Free goods

Many labels use free goods to fund co-op advertising. If a retailer has a co-op advertising program that costs $120, instead of exchanging dollars, the label may fund the advertising with product. Wholesale for a specific CD may average $12.00, so the label would send ten CDs to the retailer—being the same dollar value of the advertising program.

This kind of exchange is a win-win scenario for both players. The retailer can then sell those ten CDs for $14.00/unit, garnering $140 in revenues, which is more than the actual advertising program cost. And, the label value of the CDs on the accounting books is not that of $12.00/unit, but rather $6.00/unit— meaning that in cost to the label, the co-op advertising program was purchased for $60 total.

Although promotional activities within the store include the placement of product in designated areas, the choosing of a location or place of the actual store is paramount to the success of the business. Factors to consider are:

Location and visibility—Having built-in traffic helps a store attract more customers. Being in a mall or a high traffic area is ideal for the store selling mass-appeal product. Additionally, being visible and easy to find and access can help a store succeed.

Competition—Depending on the store’s marketing strategy, having competition nearby can detract from a store’s success. Knowledge of area businesses is key to success.

Rent—Besides inventory and employee costs, rent is a big expense that can impact profitability. Again, depending on store strategy, some retailers build their own storefront, while others rent from existing outlets (Hall, C., 2000).

Use clauses—A store must be sensitive to non-compete use clauses that can restrict business. Some malls restrict the number of record retail outlets and/or electronic store outlets to help ensure success of existing tenants.

Image—Store image reflects corporate culture along with product for sale.

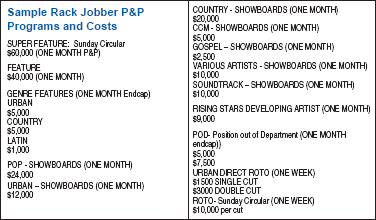

Floor plans—The store’s culture and marketing strategy is best observed in the design and layout of the floor plan. Market research observes that the longer a person is in a store, the higher the probability that the person will purchase an item, based on a marketing concept called time spent shopping (TSS). On that premise, some stores draw in their customers, creating interesting and interactive displays further back in the store. Sale items may be placed in the back, or in some cases, there may be multiple floors, all with an eye to keep the shopper in the store longer. Other stores may entice browsers with new releases right inside the front door. Others include the addition of coffee bars to boost TSS.

Genre placement, along with related items, helps define a store. Display placement, including interactive kiosks, listening stations, featured titles, and top-selling charts, helps consumers make purchasing decisions. Larger stores with broader product offerings couple music product with related items. The placement of these elements and traffic flow design can aid consumers and increase sales.

Store target market

A music store’s target market or consumer generally dictates what kind of retailer it will be. To attract consumers interested in independent music, or to attract folks who are always looking for a bargain, determines the parameters in which a store operates. Music retailers have traditionally been segmented into the following profiles:

![]() Figure 12.7 Retail store layout

Figure 12.7 Retail store layout

Independent music retailers cater to a consumer looking for a specific genre or lifestyle of music. Generally, these types of stores get their music from one-stops. Independent stores are locally or regionally owned and operated, with one or just a few stores under one ownership.

The Mom & Pop retailer is usually a one-store operation that is owned and operated by the same person. This owner is involved with every aspect of running the business and tends to be very passionate about the particular style of music that the store sells. This passion can be interpreted as being an expert in the knowledge of the genre and can be a unique resource for the consumer looking for the obscure release. Mom & Pop storeowners tend to have a personal relationship with their customer base, knowing musical preferences and keeping the customers informed about upcoming releases and events.

Alternative music stores profile very similarly to Mom & Pop stores, but with the exception that they tend to be lifestyle-oriented. An electronica music retailer may have many hard-to-find releases along with hardware offerings such as turntable and mixing boards.

Chain stores tend to attract music purchasers who are looking for deep selection of releases along with assistance from employees who have strong product knowledge. These stores are often in malls and cater to a broad spectrum of purchasers. These stores have been studied and replicated so that entering any store with the same name in any location feels very similar. Often, they have the new major releases upfront with many related items for sale, such as blank media and entertainment magazines. Chain stores traditionally buy their music inventory directly from music distributors, with warehousing and price stickering occurring in a central location. Some examples of chain stores are FYE, Hastings, and Musicland/Sam Goody.

Electronic superstores do not make the bulk of their profits from the sale of music. But rather, use music as an attraction to bring consumers into their store environments. By using loss leader pricing strategies, these stores often sell new releases for less than they purchased it, but for a limited time. Meanwhile, they have created traffic to the store in order to make money from the sale of all the other items offered such as electronics, computers, televisions, and so forth. Electronic Superstores also buy their music inventory directly from music distributors, with warehousing and price stickering occurring in a central location. Some examples of electronic superstores are Best Buy and Circuit City.

Mass merchants use the sale of music as event marketing for their stores. Each week, a new release brings customers back to their aisles with the notion that they will purchase something else while there. There is little profit in the sale of music for the mass merchant, but the offering of music is looked at as a service to customers. Often, mass merchants use rack jobbers to supply and maintain music for their stores. It is the rack jobber who initially purchases the music for the mass merchant environment. Some examples of mass merchants are Wal-Mart and Kmart

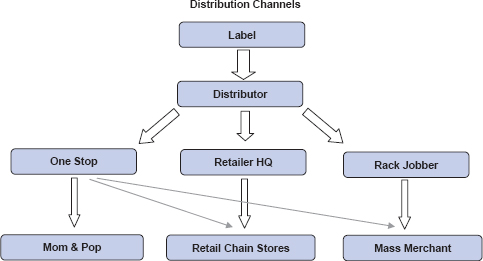

Sources of music

The following figure shows the basic flow of music as it reaches the consumer level. Recognize that one stops’ primary business is servicing independent records stores, but that they also do what is called fill-in business for all music retailers.

![]() Figure 12.8 Distribution channels

Figure 12.8 Distribution channels

Internet marketing and sales

Until recently, it was the retailers who had the brand identities that were winning the Internet sales wars. Consumers went to their favorite retail store websites to browse and purchase music, meaning the actual CD that was to be delivered to the consumer’s door. These well-known retailer sites left many start-up websites with unknown names with little traffic. As noted in the sales overview, downloading and file-swapping has become big “business,” but not perceived as a potentially profitable business … until now. Downloading activities have hurt not only the labels and their distributors, but the retailers as well. With the aggressive prosecution and education campaigns to alert downloaders as to their illegal practices, consumers are beginning to use legal downloading sites to purchase music. Sites such as iTunes, Napster, MusicMatch, Rhapsody, and yes, Wal-Mart are all experiencing a high volume of downloads, with more sites coming online soon. Well-known online sites such as Amazon and CDNow have also had an impact on retailing. For more on Internet sales and marketing, refer to Chapter 14 on Internet Marketing.

Bricks and clicks – The term given to a retailer who has physical stores and an online retail presence.

Brick and mortar – The description given to physical store locations when compared to online shopping.

Box lot – Purchases made in increments of what comes in full, sealed boxes receive a lower price. (For CDs with normal packaging, usually 30).

Buyers – Agents of retail chains who decide what products to purchase from the suppliers.

Chain stores – A group of retail stores under one ownership and selling the same lines of merchandise. Because they purchase product in large quantities from centralized distribution centers, they can command big discounts from record manufacturers (compared to indie stores).

Computerized ordering process – An inventory management system that tracks the sale of product and automatically reorders when inventories fall below a preset level. Reordering is done through an electronic data interchange (EDI) connected to the supplier.

Co-op advertising – A co-operative advertising effort by two or more companies sharing in the costs and responsibilities. A common example is where a record label and a record retailer work together to run ads in local newspapers touting the availability of new releases at the retailer’s locations.

Discount and dating – The manufacturer offers a discount on orders and allows for delayed payment. It is used as an incentive to increase orders.

Distribution – A company that distributes products to retailers. This can be an independent distributor handling products for indie labels or a major record company that distributes its own products and that of others through its branch system.

Drop ship – Shipping product quickly and directly to a retail store without going through the normal distribution system.

Electronic data interchange (EDI) – The inter-firm computer-to-computer transfer of information, as between or among retailers, wholesalers, and manufacturers. Used for automated re-ordering.

Electronic superstores – Large chain stores such as Circuit City and Best Buy that sell recorded music and videos, in addition to electronic hardware.

End cap – In retail merchandising, a display rack or shelf at the end of a store aisle; a prime store location for stocking product.

Floor designs – A store layout designed to facilitate store traffic to increase the amount of time spent shopping.

Free goods – Saleable goods offered to retailers at no cost as an incentive to purchase additional products.

Indie stores – Business entities of a single proprietorship or partnership servicing a smaller music consumer base of usually one or two stores. (Sometimes known as mom & pop stores.)

Inventory management – The process of acquiring and maintaining a proper assortment of merchandise while keeping ordering, shipping, handling, and other related costs in check.

Listening station – A device in retail stores allowing the customer to sample music for sale in the store. Usually the devices have headphones and may be free-standing or grouped together in a designated section of the store.

Loose – The pricing scheme for product sold individually or in increments smaller than a sealed box.

Loss leader pricing – The featuring of items priced below cost or at relatively low prices to attract customers to the seller’s place of business.

Margin – The percentage of revenues leftover to cover expenses as well as account for profitability.

Markup – The percentage of increase from wholesale price to retail price.

Mass merchants – Large discount chain stores that sell a variety of products in all categories, for example, Wal-Mart and Target.

Min/max systems – A store may have ten units on-hand, which is considered the ideal maximum number the store should carry. The ideal minimum number may be four units. If the store sells seven units and drops below the ideal inventory number of four, as set in the computer, the store’s inventory management system will automatically generate a reorder for that title, up to the maximum number.

National Association of Recording Merchandiser (NARM) – The organization of record retailers, wholesalers, distributors and labels.

One-Stop – A record wholesaler that stocks product from many different labels and distributors for resale to retailers, rack jobbers and juke box operators. The prime source of product for small mom & pop retailers.

Point-of-purchase (POP) – A marketing technique used to stimulate impulse sales in the store. POP materials are visually positioned to attract customer attention and may include displays, posters, bin cards, banners, window displays, and so forth.

Point-of-sale (POS) – Where the sale is entered into registers. Origination of information for tracking sales, and so on.

Price and positioning (P&P) – When a title is sale priced and placed in a prominent area within the store.

Pricing strategies – A key element in marketing, whereby, the price of a product is set in order to generate the most sales at optimum profits.

Rack jobber – A company that supplies records, cassettes, and compact discs to department stores, discount chains and other outlets and services (racks) their record departments with the right music mix.

Returns – Products that do not sell within a reasonable amount of time and are returned to the manufacturer for a refund or credit.

Sales forecast – An estimate of the dollar or unit sales for a specified future period under a proposed marketing plan or program.

Shrinkage – The loss of inventory through shoplifting and employee theft.

Source tagging – The process of using electronic security tags embedded in a product’s packaging.

Theft protection – Systems in place to reduce shoplifting and employee theft in retail stores. These systems may include electronic surveillance.

Time spent shopping (TSS) – A measure of how long a customer spends in the store.

Turn – The rate that inventory is sold through, usually expressed in number of units sold per year/inventory capacity on the floor.

Universal Product Code (UPC) – The bar codes that are used in inventory management and are scanned when product is sold.

Wholesale – The price paid by the retailer to purchase goods.

Bibliography

Hall, Charles W. and Taylor, Frederick J. “Marketing in the Music Industry”, Pearson Custom Publishing, 2000.

Gloor, Storm. From personal interview, March 2004.

National Association of Recording Merchandizers (NARM), www.narm.com.