| 13 | Grassroots Marketing |

Consumers are bombarded everyday with more commercial messages from more sources than ever before. The competition for our attention ranges from a subtle product placement in your favorite television show to an in-your-face ad from a car salesman on the radio. Ads pop-up at us while we are online, they precede theater movies, they’re on seat backs at stadiums, and they’re even in public facilities where graffiti once was posted. It is this competition for the attention of the consumer that has driven marketers to find alternative methods to connect products and services with billfolds and credit cards. This chapter presents some of those less traditional marketing tools and how they may be used to encourage the consumer to buy recorded music.

Very few concepts in business are as universally accepted as being axiomatic as is the power of word of mouth (WOM) in marketing. Everett Rogers, in the book, Diffusion of Innovations, talks about the role of “opinion leaders” in the diffusion process (see Chapter 1) and how these trendsetters can be used in facilitating word-of-mouth communication messages about a new product or other innovation (Rogers, E. M., 1995). Word of mouth is more effective at closing a deal with a consumer than any pitch from any paid medium. Word of mouth is simply someone you know whose opinion you trust saying to you, “You gotta try this!” And the companies most effective with this kind of marketing are those who give their consumers reasons to talk about products to others, and then facilitate that communication.

From the company’s standpoint, there are several basics to developing a plan to reach new consumers through word of mouth. They are:

![]() Educating people about your product or services

Educating people about your product or services

![]() Identifying people most likely to share their opinions

Identifying people most likely to share their opinions

![]() Providing tools that make it easier to share information

Providing tools that make it easier to share information

![]() Studying how, where, and when those opinions are being shared

Studying how, where, and when those opinions are being shared

![]() Looking and listening for those who are detractors, and being prepared to respond (Word of Mouth 101, 2005)

Looking and listening for those who are detractors, and being prepared to respond (Word of Mouth 101, 2005)

Among the most popular ways to effectively use word-of-mouth marketing and promotion in the recording industry is through the artist fan club. The club is a network of people who have a passion for the music of the artist and who are willing to be actively involved in promoting the career of the artist. Members of the club are regular chat room visitors, bloggers, video bloggers, message board respondents, and hosts of discussion groups.

This discussion of word-of-mouth marketing is not intended to be a short course on fan club development, but the elements of it as a catalyst for “spreading the word” are among the best central strategies a label can use to draw from the strength of the idea. Word of mouth is often compared to the work of the evangelist, and fan club members easily fit the definition. Energizing them and arming them with available tools has the potential to spread positive information about the artist in geometric proportions.

Word-of-mouth marketing takes several forms. Among those are:

Table 13.1 Word-of-mouth style |

|

Word-of-mouth style |

Elements of the style |

Buzz Marketing |

Using high profile people or journalists to talk about the artist. |

Viral Marketing |

Creating interesting, entertaining, or informative messages electronically by email and passed along to targets. |

Community Marketing |

Forming or supporting fan clubs or similar organizations to share their interest in the artist; provide access to music, videos, tour schedules, etc. |

Street Team Marketing |

Organizing and motivating volunteers to work in personal outreach locally. |

Evangelist Marketing |

Cultivating key opinion leaders and tastemakers to spread the word about the artist. |

Product Seeding |

Giving product samples and information about the artist to key groups and individuals. |

Influencer Marketing |

Identifying other artist fan clubs and key members of those clubs to help spread the word about the artist. |

Cause Marketing |

Working with charities and causes that the artist supports. |

Conversation Creation |

Creating catch phrases, highlighting lyric lines, creating emails, or designing fun activities to start the word-of-mouth activity. |

Referral Programs |

Creating tools that let help fans refer the artist to their friends. |

Adapted from www.womma.org. |

|

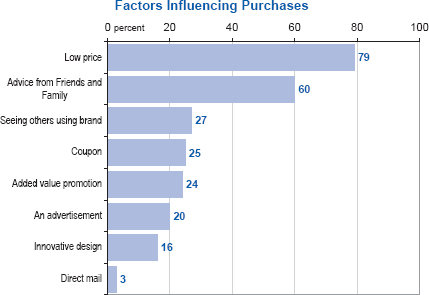

![]() Figure 13.1 Factors influencing purchases (Source: Haynmarket Publishing Services)

Figure 13.1 Factors influencing purchases (Source: Haynmarket Publishing Services)

The importance of word-of-mouth marketing was demonstrated by a U.K. trend-watcher in its study in 2002 that shows the primary motivators for people to try a new product or a new brand. Translating this to apply to a new artist or new music for a record label, you can see by the chart in Figure 13.1 the importance of word of mouth.

Seeing the strength of “advice from friends and family” (60%), and “seeing others using the brand” (27%), suggests that word of mouth can have a powerful influence on the decision of a consumer to try and to buy new music.

Word-of-mouth promotion as defined by Malcolm Gladwell in his book, The Tipping Point, shows the marketer that this seemingly simple strategy can actually have a deep-rooted sophistication. He suggests there are three rules to its effectiveness. First, there is the law of the few people who are connected to many others, and who can spread the word about a product in ways that have epidemic proportions. Second, the law of stickiness suggests that the idea shared by the connector has to be memorable and must be able to move people to action. And third, the power of context means that people “are a lot more sensitive to their environment than they may seem” (Gladwell, M., 2000a) and the effectiveness of word of mouth has a lot to do with the “conditions of, and circumstances of, the times and places” (Gladwell, M., 2000b) where it happens.

A great deal of care must be taken to set up a word-of-mouth promotion to make it effective.

The World Wide Web has quickly become one of the most effective media for word-of-mouth marketing, and we have dedicated a chapter in this book to the use of the Web in marketing plans. But briefly, in its online white paper, Consumer Generated Media, Intelliseek writers Pete Blackshaw and Mike Nazzaro point to Internet word-of-mouth vehicles they see as the fastest-growing and most viable. They include, “consumer-to-consumer e-mail, postings on Internet discussion boards and forums, consumer ratings websites for forums, blogs (short for weblogs, or digital diaries), moblogs (sites where users post digital images/photos/movies), video blogs, social networking sites, and individual websites” (Intelliseek, 2005). The impact of consumer generated media, or word-of-mouth marketing, is estimated to total over 2 billion web postings by the end of 2006. These reviews, ratings, and postings are building into a massive archive of consumer opinions, nearly doubling the 2004 estimate (Presentation at Ad-Tech, 2004).

Sometimes an aggressive and competitive spirit shows itself in word-of-mouth marketing as fans or consumers are deceived. Spamming is occasionally used, and some use automated software to post to message boards online. Marketers may try to hide the knowledge that they are behind a big word-of-mouth program. And there are occasions when people represent that they are fans, when they are actually the hired help. One fan club president lost her job when it was learned that the “Gulf War wives” requesting a certain song on the radio were actually just fans of the artist. The credibility of the sources of word-of-mouth campaigns will ultimately determine whether the effort was effective, so it is important to keep participants reminded about the ethics of this type of promotion.

While word-of-mouth marketing has traditionally been the tool of independent and private record labels, major label EMI has joined in a big way. The music giant has created an alliance with Procter & Gamble to test their new music through P&G’s American network of 200,000 teens and young adults. The record company plans to use the young people to help it decide which singles to release by sending early copies of new releases, and then they plan to use the network for word-of-mouth promotion to others (Rees, J., 2004).

For the record label, coordinating the energy and passion for artists through their fans can generate sales. Dave Balter, owner of BzzAgent, a word-of-mouth marketing firm, says, “The key is about harnessing something that’s already occurring. We tap into people’s passions and help them become product evangelists” (Strahinich, John, 2005). And that is the essence of the word-of-mouth marketing strategy as it is applied to the recording industry.

The idea of street teams is an adaptation of the strategy of politicians everywhere: Energize groups of volunteers to promote you by building crowds, creating local buzz, posting signs, and rallying voters. There isn’t a lot of difference between political volunteer groups and artist street teams.

For the artist, they are volunteer ambassadors who quite literally promote personal appearances and music. For the record label, the ultimate rallying point is getting consumers to purchase the artist’s music. While many artists use street teams today, they were originally formed in order to promote music that was not radio-friendly. Without radio airplay, creators of alternative music sought other ways to connect consumers with their music, and employing street teams became an effective way to do that.

Street teams are local groups of people who use networking on behalf of the artist in order to reach their target market. These team members make up the core of the fan base of the artist and often have the deepest passion for the music and message of the artist. Often they are friends and fans of the artist. Some refer to street team members as “marketing representatives” who promote music at events and locations where the target market can be found. Often these places are tied to the lifestyle of the target market such as at specialty clothing stores, coffee houses, and at concerts of similar acts. A key to effective street teams is for members to understand where to find the target market of the artist and to provide tools and guidance on how to communicate to the target (Tiwary, V. J., 2002)

Case study: Columbia Records and Switchfoot

“UBI was enlisted to help introduce the band Switchfoot, and their latest album, “The Beautiful Letdown”, to the masses. Switchfoot had found success in the Christian Rock format, but their label was interested in creating crossover appeal by targeting college campuses, lifestyle/community locations, clubs/bars, and record stores in 10 major cities across the United States. The goal was to increase awareness of the band, to bring attention to their live performances and to drive sales of their new release.

“Universal Buzz Intelligence mobilized their corps of highly trained operatives for an intense 9 week promotional campaign in 10 major markets. The campaign focused on the distribution of promotional materials and other collateral marketing materials throughout college campuses and the communities that surround them. The guerilla marketing effort focused heavily on driving retail store sales for “The Beautiful Letdown” album, as well as promoting the band’s live tour dates.

“By all accounts the Switchfoot release “The Beautiful Letdown” far exceeded label expectations with over one million copies sold to date (the band sold an aggregate of 100,000 albums for their previous three releases). Of the 10 markets covered by UBI, the band realized 7 sold out performances. In addition, six of their top ten selling markets were markets covered by UBI (which had not previously been strong markets for the band), with the remaining 4 cities in the UBI campaign falling within the bands top 25 selling markets. The bands crossover popularity has brought them video exposure on MTV and The Fuse Network.”

Source:

![]() Figure 13.2 Universal Buzz case study (Source: Universal Buzz Intelligence)

Figure 13.2 Universal Buzz case study (Source: Universal Buzz Intelligence)

Street teams originally were formed as a way to reach consumers by companies who either did not have the resources for mass-media marketing, or to reach segments of the market who were not as responsive to mass mediated messages as they are to peer influence (Holzman, K., 2005). Now, major marketing and advertising agencies have started to realize that street teams are an effective form of youth marketing.

Among the tools that may be provided to the street team members are postcards and flyers, email addresses to contact local fans, small prizes for local contests, Web addresses for music samples, actual CD samplers to give away at appropriate events, advance information about tour appearances, and release dates for new music. Street team members may engage in sniping—the posting of handbills in areas where the target market is known to congregate. Some labels economize on printing by emailing flyers and posters to local street team coordinators, and asking them to arrange for printing.

Street teams require servicing. The most important thing a street team coordinator can do is to find ways to say “thanks” to the street members. Volunteers for causes require a measure of recognition for their effort in order to keep them energized, and it is no different with those working for free on behalf of an artist. The first thing the label coordinator must do is to regularly communicate with core members of the team. Keep them current on the planned activities of the artist, and make them feel they are important. Provide incentives to the extent the budget will allow. Incentives can be CDs, tee shirts, meet-and-greets with the artist, and free tickets.

The hierarchy of street team management often begins at the label with a coordinator, who recruits regional street team captains who then coordinate at the local level. Data captured by artists through their website or via links from the label’s website becomes an important building block for street teams.

While major labels often have in-house grassroots or “new media” departments to run street teams, there are several independent or outside marketing companies that specialize in street team marketing. The advantage of using one of these companies is that they often promote other lifestyle products and the opportunities for cross-marketing are increased. As mentioned earlier, EMI Group teamed up with Tremor, a street team division of Proctor and Gamble, to not only promote new music, but to coordinate music promotion with P&G’s products.

Some of the outside marketing companies used for street marketing are Street Attack, Buzz Intelligence, and Streetwise Concepts and Culture. Street Attack boasts on their website that their understanding of street psychology and Generation Y mindset makes them specialists in building street teams (www.streetattack.com, 2005). Buzz Intelligence boasts that V2, Virgin, Arista, Interscope, Sony, Universal, Geffen, Atlantic, Blue Note and Warner Bros. are among their clients. Streetwise claims A&M, Atlantic, Capitol, Columbia, Epic, Epitaph, Geffen, Interscope, Island, Maverick, Razor & Tie, RCA, Reprise, Sanctuary and Universal have used their street marketing services (www.streetwise.com, 2005).

The subject of guerilla marketing must begin with Conrad Levinson. He is the author of the best-selling book, Guerilla Marketing, first published in 1984. Levinson is credited with coining the term, which generally means using nontraditional marketing tools and ideas on a limited budget to reach a target market. In Levinson’s words, guerilla marketing is “achieving conventional goals, such as profits and joy, with unconventional methods, such as investing energy instead of money” (www.gmarketing.com, 2005).

In the recording industry, much of the activity of street and e-teams is basic guerilla marketing. Postings in chat rooms, handing out music samplers, and giving promotional buttons and bumper stickers at the competition’s concerts are examples of low-cost, but effective guerilla marketing. Figure 13.3 includes a list of guerilla marketing tactics. While they may not directly apply to promoting music, many of them can be developed and adapted for specific uses by a label to help market recorded music.

Guerilla tactics in the marketplace aren’t limited to smaller labels with limited resources. When Mike Kraski was vice president of marketing at Sony Nashville, he wanted to find a way to encourage Wal-Mart store associates to become familiar with their new music so that callers to the store could be told the item was available. He announced to the stores he was beginning a promotional campaign where someone from Sony Nashville would occasionally call Wal-Mart record departments and ask about Sony new releases. To those associates who were able to tell the caller about the new music, he gave a limited number of big screen Sony television sets as prizes.

2. Marketing calendar

3. Niche/positioning

4. Name of company

5. Identity

6. Logo

7. Theme

8. Stationery

9. Business card

10. Signs inside

11. Signs outside

12. Hours of operation

13. Days of operation

14. Window display

15. Flexibility

16. Word-of-mouth

17. Community involvement

18. Barter

19. Club/Association memberships

20. Partial payment plans

21. Cause-related marketing

22. Telephone demeanor

23. Toll-Free phone number

24. Free consultations

25. Free seminars and clinics

26. Free demonstrations

27. Free samples

28. Giver vs taker stance

29. Fusion marketing

30. Marketing on telephone hold

31. Success stories

32. Employee attire

33. Service

34. Follow-up

35. Yourself and your employees

36. Gifts and ad specialties

37. Catalog

38. Yellow Pages ads

39. Column in a publication

40. Article in a publication

41. Speaker at any club

42. Newsletter

43. All your audiences

44. Benefits list

45. Computer

46. Selection

47. Contact time with customer

48. How you say hello/goodbye

49. Public relations

50. Media contacts

51. Neatness

52. Referral program

53. Sharing with peers

54. Guarantee

55. Telemarketing

56. Gift certificates

57. Brochures

58. Electronic brochures

59. Location

60. Advertising

61. Sales training

62. Networking

63. Quality

64. Reprints and blow-ups

65. Flipcharts

66. Opportunities to upgrade

67. Contests/sweepstakes

68. Online marketing

69. Classified advertising

70. Newspaper ads

71. Magazine ads

72. Radio spots

73. TV spots

74. Infomercials

75. Movie ads

76. Direct mail letters

77. Direct mail postcards

78. Postcard decks

79. Posters

80. Fax-on-demand

81. Special events

82. Show display

83. Audio-visual aids

84. Spare time

85. Prospect mailing lists

86. Research studies

87. Competitive advantages

88. Marketing insight

89. Speed

90. Testimonials

91. Reputation

92. Enthusiasm & passion

93. Credibility

94. Spying on yourself and others

95. Being easy to do business with

96. Brand name awareness

97. Designated guerrilla

98. Customer mailing list

99. Competitiveness

100. Satisfied customer

![]() Figure 13.3 One-hundred marketing weapons Source: Jay Conrad Levinson, www.gmarketing.com/articles.

Figure 13.3 One-hundred marketing weapons Source: Jay Conrad Levinson, www.gmarketing.com/articles.

Basic grassroots marketing, whether you call it word of mouth, street teams, e-teams, peer-to-peer, guerilla marketing, viral marketing, or the latest term du jour, can create an environment that can set a record label’s marketing plan and results apart from those of competing artists. One of the biggest challenges of a label-marketing department is to find new and unique ways to present its product to consumers. Including an element of grassroots in the marketing plan can create a plan that steps away from overused templates to add a unique element.

Bloggers – Short for weblogs, and refers to those who write digital diaries on the Internet.

Grassroots marketing – A marketing approach using nontraditional methods to reach target consumers.

Guerilla marketing – Using nontraditional marketing tools and ideas on a limited budget to reach a target market.

Moblogs – Websites where individuals post still images and videos.

Marketing representatives – Another term sometimes used for members of a street team.

Sniping – The posting of handbills in areas where the target market is known to congregate.

Street teams – Local groups of people who use networking on behalf of the artist in order to reach their target market.

Video bloggers – Also known as vloggers, they are the video counterparts to bloggers except the content contains audio and video.

Bibliography

Gladwell, M. (2000a). Tipping Point, New York: Little, Brown, and Company, pp. 29.

Gladwell, M. (2000b). Tipping Point, New York: Little, Brown, and Company, pp. 139.

Holzman, K. (February 20, 2005). Effective Use of Street Teams. http://www.indiemusician.com/2005/02/effective_use_o.html. Music Dish Network.

Intelliseek (2005). Word-of Mouth in the Age of the Web-Fortified Consumer. www.intelli-seek.com.

Presentation at Ad-Tech (2004). Measuring Word of Mouth, Ad-Tech. New York, November 8, 2004, Word of Mouth Marketing Association.

Rees, J. (Nov 14, 2004). EMI Clinches Research Deal, Associated Newspapers. (LexisNexis Acacdemic).

Rogers, E. M. (1995). Diffusion of Innovations (4th edition), New York: The Free Press.

Strahinich, John (January 23, 2005). What’s all the buzz; Word-of mouth advertising goes mainstream, The Boston Herald. (LexisNexis Academic).

Tiwary, V. J. (2002). Starting and Running A Marketing/Street Team. http://www.starpolish.com/advice/article.asp?id=31.

Word of Mouth 101 (2005). Word of Mouth Marketing Association www.womma.org.

www.gmarketing.com (2005). www.gmarketing.com/what_is_gm.html.

http://www.streetattack.com (2005). http://www.streetattack.com/Default.aspx.

http://www.streetwise.com (2005). http://www.streetwise.com/indexnew.php.