| 16 | The International Recording Industry |

International recording industry

The sale of recorded music overseas offers challenging, yet potentially rewarding opportunities for future growth of the record business. Countries with well-developed music markets are considered to be mature markets, characterized by slow growth and saturation. Market saturation is when the quantity of products in use in the market place is close to or at its maximum. Newer markets are considered emerging markets and offer the potential for rapid expansion. This opportunity is not without complications, the most critical being music piracy.

In this chapter, we will examine how markets are analyzed internationally and what opportunities and challenges the international recording industry faces.

Each year, Reed MIDEM holds an international music conference in Cannes, France. It is an opportunity for global networking among music industry professionals. The event includes a large trade show and seminars on international issues in the recording industry. It is considered by many in the U.S. record business to be the most important international conference.

The predominant organization for monitoring and supporting the recording industry internationally is the International Federation of Phonographic Industries (IFPI). The goals of the IFPI include fighting international piracy, fostering the development of music industries globally, and compiling and reporting economic information about the recording industries.

According to the IFPI, global sales of recorded music fell in 2003 for the fourth straight year, a four-year total decline of 16.3%. As a result, the major record labels have further consolidated and trimmed their payrolls to reduce overhead. Global sales were considered flat for 2004, with the growth of DVD music videos and digital downloads offset by a slight reduction in physical audio sales.

The recording industry is considered a mature industry. Mature industries are characterized by the presence of a structure called an oligopoly. An oligopoly is defined as a situation in an industry where the market is dominated by just a few companies who control most of the market share. By contrast, new, emerging industries are characterized by extreme competition among many small players who are all competing to increase their market share as the industry grows and expands.

Usually at the early stage of marketplace development, the barriers to entry are low, and companies already in the marketplace are not successful in preventing startups from encroaching on their markets. Eventually, the industry is flooded with suppliers and this leads to a shakeout, with some of the more successful small players extending their market share through acquisitions, mergers and driving out the competition. The motivations for expanding and acquiring other companies include: (1) an increase in market share, (2) reduction of costs through economies of scale, (3) more control over the market including protecting pricing and preventing the entry of upstarts. Eventually, these “chains” or medium-sized companies drive out most of the small entrepreneurs or force them into specialized niche markets. At that point, the medium-sized firms begin to buy up or merge with each other until ultimately, just a few major firms control most of the marketplace—an oligopoly. Examples include the tobacco, automotive and soft drink industries, which are all dominated by two or three companies controlling over three-fourths of the market share.

Economists differ in their evaluation of whether an oligopolistic marketplace stifles product diversity or enhances it. Some argue that innovation will more often occur in an oligopolistic market structure because firms have better ability to finance research and development (Vaknin, S., 2001). With less competition and larger market share, these companies can better afford the costs and risks associated with developing and introducing new products (new artists in the case of the recording industry) than could a market situation with many smaller players.

Others believe in a negative relationship between industry concentration and product diversity. Their research suggests that complacency and status quo are the norm—that is, as long as these few companies control the marketplace, there is no incentive to invest in research and development (Burnett, R., 1996). Several scholars have noted that periods of high industry concentration in the recording industry (fewer labels controlling more of the market share) have been accompanied by periods of low product diversity (fewer top-selling titles). This trend started to change in the 1990s when major record labels realized that product development was more effective with smaller business units, such as independent labels. Major labels made great attempts to forge partnerships and partial ownership of the most successful independent labels without completely absorbing them into the larger company. Joint ventures, pressing and distribution deals, vanity labels and imprints became the norm, thus preserving the innovative edge of the indie label environment.

It is also believed by some scholars that consolidation leads to higher pricing as the few remaining firms have a lock on the marketplace. This notion has been refuted by other economists who have found that mergers do not always drive prices higher. Companies fear losing market share to new entrants and existing competitors. This is especially true in a market where entry by new players is easy and cheap. In the recorded music industry, technology has enabled startup companies to record top quality products at a fraction of the traditional costs, and use the Internet as an inexpensive way to market and distribute those products. In a report commissioned by UNESCO, David Throsby (2002) states “… [the majors’] capacity to continue to exert the market power that they have enjoyed in the past is seriously threatened by the fluidity and universal accessibility of the internet.”

Universal Music, the largest of the major music companies (when publishing is included), slashed its retail prices in 2002 in an effort to recapture customers and improve market share. However, as a condition of the new pricing strategy, the company did demand that retailers provide them with 32% of their shelf space and promotional considerations. So far, none of the other major labels has followed.

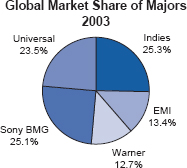

As a result of consolidation in the industry throughout the 1980s, 1990s and into the new millennium, the music industry is now dominated by four major companies who control about 70–80% of the world music market. These companies are Warner Music Group, Universal Music Group, Sony BMG, and EMI.

![]() Figure 16.1 Global market share of majors (Source: IFPI)

Figure 16.1 Global market share of majors (Source: IFPI)

Universal Music Group (UMG) was the largest of the major labels until the Sony-BMG merger, coupled with a drop in market share, caused them to slip into second place, according to some analysts. The company controls about 25 record labels, including Interscope, Island, Def Jam, Mercury, Motown, Geffen and A&M. UMG is a subsidiary of the French telecommunications giant Vivendi Universal, which includes Universal Music Publishing, the world’s third largest music publisher. Universal Music Group has operations in 71 countries. Universal’s market share is strongest in the United States and Europe and weaker than other majors in Japan and Latin America.

EMI, with a 13.4% market share in 2003, did rank second behind Universal until the Sony BMG merger (IFPI, 2004a). Home to labels such as Blue Note, Capitol and Virgin, EMI has the smallest market share of the majors in the United States, but has done remarkably well in Africa, Europe and Australasia. EMI owns the world’s largest music publishing company, with rights to over a million songs, but has no other communications or entertainment holdings. In 2003, EMI entered into acquisition talks with Warner Music Group, but lost out to former Seagram head Edgar Bronfman, Jr., who purchased Warner Music Group for $2.6 billion.

Warner Music Group (WMG) was purchased from AOL-Time/Warner by a group of private investors including Edgar Bronfman, Jr. and went public in May 2005. With labels such as Atlantic, Elektra, Reprise, and Rhino, WMG has a strong catalog but continues to lose market share with just 12.7% in 2003. Warner’s share is strongest in North America and Latin America, and weak in Africa and Japan.

Sony Music Entertainment (SME) recently merged (in a joint venture that includes only the record label divisions) with BMG to rival UMG in market share. Before the merger, SME had a global market share of 13.2%. Sony has a strong presence in Latin America and, among the major labels, the strongest presence in Japan—home of the parent company. Sony produces consumer electronic products including the successful Sony PlayStation® and cell phones through its Sony/Ericcson joint venture. Labels include Columbia and Epic, and music sales account for about 7% of total revenue. The merger with BMG is designed as a 50-50 joint venture limited to the label division, and is called Sony BMG.

Bertelsmann Music Group (BMG), now a partner with Sony, is owned by the German media giant Bertelsmann. Bertelsmann has publishing, music, and broadcasting operations in nearly 60 countries. It owns the top book publisher Random House, several major newspapers, and has a 75% stake in magazine publisher Gruner + Jahr, which publishes Family Circle and Inc. Best known record labels include Arista and RCA, J Records and LaFace.

In 2002 and again in 2003, the independent label sector accounted for just over 25% of global sales. The indie market share is lowest in North America with 16%, and quite low in Europe and Australasia with 20%. The indie sector is highest in Japan, where several large regional labels contribute to the indie market share of 55.3%.

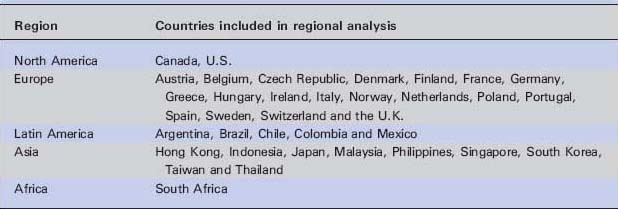

The IFPI reports industry statistics for regions as well as markets in individual countries. Calculations based on regions include only the most influential markets in each region.

Table 16.1 Countries included in regional analysis (Source: IFPI)

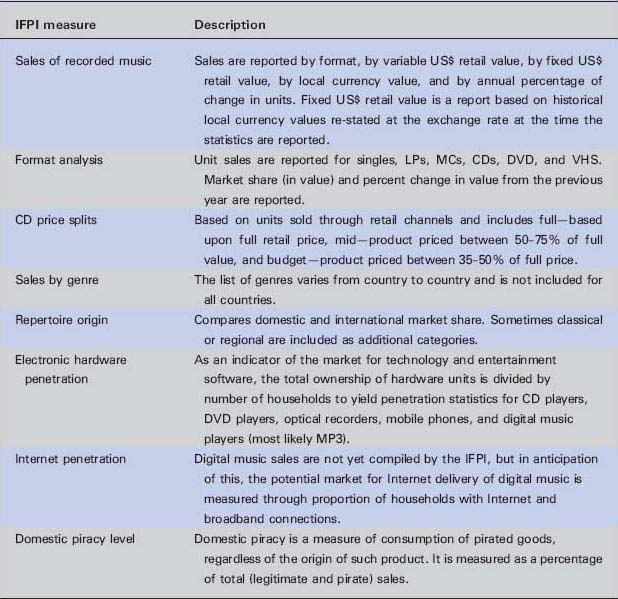

Before one can examine individual geographic markets, it is necessary to understand how the IFPI evaluates national and regional markets. Recorded music sales include an estimate of legitimate retail sales including singles, LPs, CDs, SACD, DVD Audio, MiniDisc (MD) and others. Final retail value is estimated and converted to U.S. currency values. Price splits are examined—the relative market share of topline product (full), midline product, and budget product. Repertoire origin is examined, which evaluates the relative market share of music originating within the country (domestic) to that which is produced elsewhere (international). World ranking and piracy level are evaluated for each market. The IFPI also looks at sales by genre and retail channels.

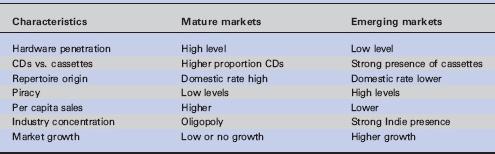

The proliferation of consumer electronic devices is seen as an indicator of market potential, and penetration levels of CD players, DVD players, optical recorders, digital music devices, mobile phones and Internet connections are evaluated by the IFPI for each of the 70 member countries. It is also an indicator of the maturity level of the market. Mature geographic markets are those that exhibit a high penetration level of consumer electronic devices, a higher level of domestic repertoire, a higher proportion of sales in newer formats, lower piracy rates, and higher per capita sales. There is less potential for growth in mature markets, which, by their very nature, are saturated—meaning that consumers are not likely to increase their music purchases from one year to the next.

A comparison of emerging markets and mature markets

Developing (or emerging) markets differ from mature markets on several factors. Emerging markets are commonly found in countries that are still growing their industrial sector, moving from predominantly agricultural products to manufacturing. As this happens, workers have more disposable income and more time for recreation and entertainment. Emerging markets have more potential for growth as consumers are still purchasing their first recorded music players. Differences are also evident in the record industries. As emerging markets grow, the ability to nurture and develop local musical talent increases, ultimately increasing the amount of domestic repertoire. However, Throsby argues that the proportion of domestic repertoire is subject to decrease in growth markets. He claims that as international music becomes more available in these markets, and as incomes rise and consumer tastes change, consumer demand for international repertoire increases and the proportion of domestically produced product declines.

Table 16.2 IFPI measures (Source: IFPI)

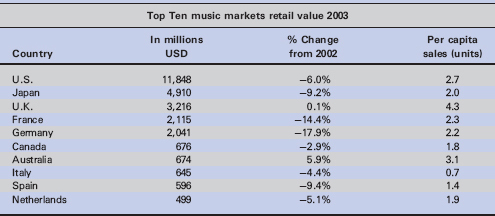

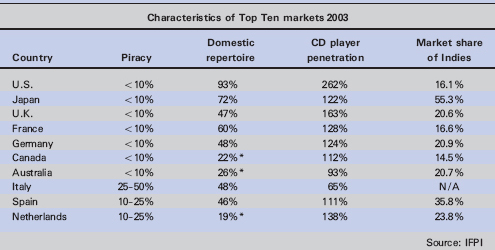

A comparison of top ten markets and developing markets

The top ten markets all show characteristics of mature markets with the following exceptions. The market share of Indies in Japan is over 50%, due mainly to strong local labels that provide much of Japan’s domestic repertoire. Despite the statistical figure for market share of indies, the market in Japan can be characterized as an oligopoly. Domestic repertoire is low for Australia and Canada which import music from other English-speaking countries, most notably the United States and United Kingdom. It is also low for the Netherlands, which imports much of their music from the rest of Europe. The piracy rate is higher in Italy, due to the presence of pirate networks and an influx of popular pirated music from nearby San Marino and other places.

Table 16.4 Characteristics of Top Ten markets

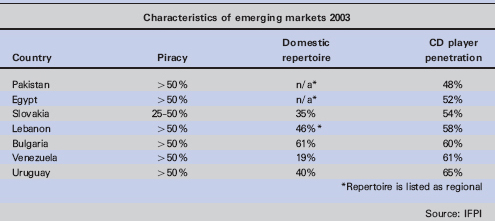

For purposes of comparison to the top ten markets, emerging markets were selected from the IFPI world-ranking list and includes a sample of markets in the lower half of the chart. Attempts were made to include countries from differing geographic regions. Piracy levels are substantially higher and domestic repertoire is lower in most cases. Information on market share of labels and hardware penetration is not available for these smaller markets.

Table 16.5 Characteristics of emerging markets

The top ten markets for recorded music account for 85% of world sales in dollar value. Mexico and Brazil have recently fallen from the top ten with reduced sales resulting from an increase in piracy. Only one market in the top ten—Australia—experienced growth in the year 2003 (Broward Daily Business Review, 2004). Australia has recently reversed its ban on parallel imports, which led to a unit increase of 2.5% for 2000, but a value decrease of —5.2%, indicating an overall drop in retail prices. In 2001, Australia experienced a 14.4% increase in units, with only an 8.0% increase in value—further evidence of price reduction.

In 2004, volume growth of 2.8% in the U.S. and 4.5% in the U.K. helped stabilize the global market. Together, these two countries make up 47% of the world’s value in sales (IFPI press release, March 22, 2005). The sale of digital downloads increased more than tenfold in 2004, to over 200 million tracks in the four major digital music markets of the United States, United Kingdom, France and Germany. Elsewhere, overall markets were mixed for 2004: down for Germany and Japan, up for Latin America, leaving the industry flat.

The 6.6% drop in global recorded music sales in 2003 marked the fourth consecutive year of decline. The IFPI attributes the decline to three factors: (1) illegal downloading and burning, (2) competition from other entertainment sectors, and (3) economic downturn.

Issues and challenges to marketing recordings globally

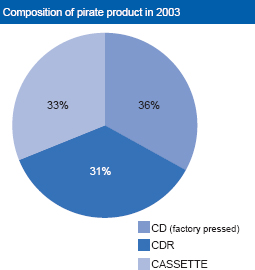

The primary threat to the international recording industry is piracy. In 2003, 40% of all recordings sold worldwide were pirated copies. Over two-thirds of pirated product sold in 2003 was on discs. In 2003, disc piracy increased by 45 million units. The format of pirated product varies from market-to-market. Pressed discs dominate the pirate market in Asia and Russia, while CD-R accounts for the majority of pirate product in Latin America, North America and Europe. The IFPI examines piracy from two perspectives: (1) the production of pirated goods, and (2) the consumption of pirated goods. The consumption aspect is termed domestic music piracy, while most production issues deal with “pressing capacity.”

Production

Pirated recordings include factory pressed CDs, where music albums are copied on blank discs, and pirated cassettes. The market for CD-R has grown in recent years, especially in more mature markets.

![]() Figure 16.2 Composition of pirated product in 2003 (Source: IFPI)

Figure 16.2 Composition of pirated product in 2003 (Source: IFPI)

In markets where production of factory-pressed pirate CDs is high, the IFPI examines pressing capacity. This is an examination of all the CD factories’ manufacturing capacity and a comparison with the legitimate demand for legal discs (of all software) in markets served by those manufacturers. For instance, Taiwan has factories capable of producing 7.9 billion units per year, but there is only a local demand for 270 million units in areas served by these producers. The IFPI claims that overcapacity is a key factor in the spread of disc piracy, including recorded music, movies and computer software. Various measures are used to monitor production in factories suspected of producing illegal copies (see section on anti-piracy efforts). The Asia-Pacific region is the primary location for factory-pressed discs, feeding illegal music markets around the world.

Piracy operations have recently been linked with organized crime as optical discs become a commodity linked with drug trafficking, illegal firearms, money laundering and even the funding of terrorist activities. Some recent raids on illegal music production facilities have netted caches of other contraband.

Consumption

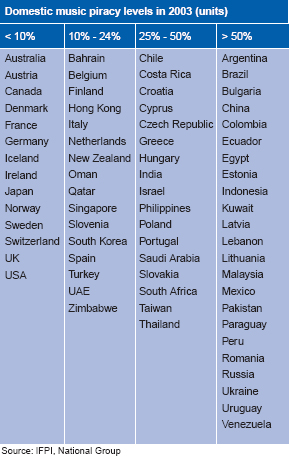

The IFPI also looks at consumption of pirated product by analyzing domestic piracy levels for each member country. Countries that show a high level of domestic piracy are targeted in anti-piracy efforts including crackdown on distribution and importation.

![]() Figure 16.3 Domestic music piracy levels (Source: IFPI)

Figure 16.3 Domestic music piracy levels (Source: IFPI)

Anti-piracy efforts

The IFPI has been working with government organizations to reduce piracy through the following measures:

1. Encouraging copyright legislation and adequate enforcement, including monitoring borders and educating local law enforcement officials.

2. Regulation of optical disc manufacturing facilities, including implementing identification coding, and plant inspections.

3. Consumer awareness: Effective prosecution and deterrent penalties. Education and consumer awareness programs. Making local governments aware of the adverse effects on the development of local artistry.

Parallel imports are defined as imported genuine copyright goods for resale by an agent other than the local authorized distributor. In other words, the importing of copyright goods into a country that were lawfully made in a foreign country, without obtaining permission of the holder of the copyright for those goods in the recipient country. In the recording industry, this occurs when a particular title is imported from another country when a domestic version of the same product is released in that country. Parallel imports are considered a problem when differential pricing policies are in effect. Recorded music is priced based upon what the market will bear, and that varies from country to country. As a result, prices are significantly lower in some countries. Problems occur when manufacturers attempt to maintain pricing policies that are not competitive with the imported version of the same product.

This is currently an issue in the prescription drug industry. Consumers want the ability to import cheaper prescription drugs from Canada. Drug manufacturers are attempting to restrict this practice through government legislation, therefore making the importation practice illegal. This allows the drug companies to maintain higher prices in the United States for the same drugs sold for lower prices in Canada.

Currently, the United States has no such restrictions for the importation of licensed recorded music. As long as the music is a legally licensed copy, it can be imported into the United States and sold alongside the version released for sale in the United States. Until recently, Australia had laws against the importation of recorded music. As a result, Australian consumers paid more for CDs than consumers in other comparable countries. Consumer groups and retailers petitioned the government and the restrictions were lifted. Also, policies in the European Union call for the gradual abolishment of tariffs and trade restrictions, allowing for parallel imports among member countries. While this practice is good for consumers and retailers, it causes problems for manufacturers.

The primary problem with parallel imports for manufacturers is that it undermines differential pricing policies by leveling the playing field, usually to the lowest available retail price. Parallel imports also create problems with customer support, as local agents are sometimes called upon to offer warrantee service on products purchased elsewhere. The imports may also cause problems for local agents who pay for marketing expenses, only to see the consumer demand they have created met with purchases elsewhere. Licensing also becomes less profitable as local agents may hesitate to pay licensing fees for fear that they may not be able to recoup the costs of licensing, manufacturing and marketing.

Parallel imports are also subject to erratic variations in exchange rates. In the 1990s, when the British pound was low compared to the German mark, German retailers were ordering their CDs from British suppliers, thus forcing TVG-WD, the top German music rackjobber, into bankruptcy. Several years later, when the British pound rose against the mark, these retailers could no longer afford to order CDs from the United Kingdom, and found the distribution infrastructure in Germany was now lacking. Now that the European Union has adopted a standard currency, this will no longer be a problem.

The DVD industry has avoided problems with parallel imports by selling systems in Asia that are not compatible with systems sold in the United States. Therefore, DVD movie titles sold in Asia will not work on DVD players owned by U.S. consumers.

It is still a common practice in the recording industry among the nonmajors to license recordings to foreign labels to manufacture and sell in their own territory. Under this arrangement, the original record label grants a foreign record label a license to issue an artist’s recording in its local or regional territory, as specified by the terms of the agreement. The licensor (original label) provides the licensee (foreign label) a master recording and artwork for the licensee to reproduce, distribute and market. The licensor is paid a percentage of the local published price to dealer (PPD), which is usually between 8–17% of the retail price (Lathrop, T. and Pettigrew, J. Jr., 1999).

In the absence of parallel imports and other forms of transshipment, licensing can be quite profitable for the licensee. However, in the spirit of global trading, many nations have reduced barriers to parallel imports, thus undermining the value of licensing. Also, Internet marketing and commercial music downloading services have reduced the effectiveness of territorial licensing by allowing the original record label to distribute globally without relying on other labels internationally to make recordings available on the local level. Licensing is still effective when a physical presence in local retail stores is important.

Every nation that has an independent currency usually has one that fluctuates in value relative to the currencies of other nations. Although a few countries officially fix their exchange value to a key currency, the exchange rates between most currencies is primarily determined by market forces and can be erratic when engaging in international commerce. Currency rates are usually cyclical. If the U.S. dollar is strong, American consumers can easily afford to purchase imported goods. But products produced in the United States can become unaffordable overseas. As a result, the demand for U.S. goods is reduced, thus reducing the demand for U.S. dollars. According to the purchasing power parity theory, exchange rates will tend to adjust over time so that purchasing power will return to a status quo (The Foreign Exchange Market, 2004).

Not all countries allow their currency values to fluctuate on the open market. Some countries officially fix or peg their currency to that of another country. For example, China currently has their currency pegged to the U.S. dollar. Hong Kong, Saudi Arabia and Egypt also have their currencies pegged to the U.S. dollar. The main advantage of a fixed-rate system is that it removes the risks associated with unpredictable fluctuations in exchange rates over time. The disadvantage is that it ignores market demands for currency and requires countries to maintain large reserves of foreign currency to supply the market when there is an excess demand for them at the official exchange rate.

Fluctuations in currency value can interfere with sales expectations and are beyond the control of the marketing efforts of a company (see section on parallel imports). They can discourage many people from making foreign investments. To overcome this, the European Union has adopted a standard currency, the Euro, in an effort to stabilize pricing and encourage commerce among its member nations.

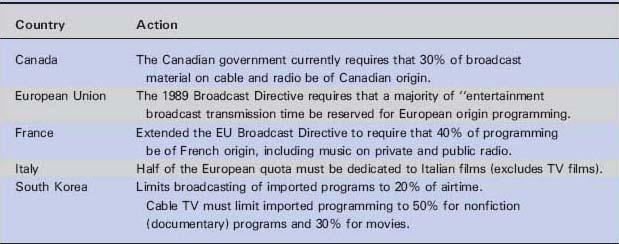

Global cultural industries that include movies, music, television, books and magazines, and fashions are considered a threat to cultural diversity around the world. Since cultural goods are often mass-produced, there is homogeneity among these goods. As a result, consumers everywhere may wear the same styles and listen to the same music. The underlying assumption is that this will lead to cultural homogenization and a loss of the local culture. The term cultural imperialism is used to describe a system where a universal homogenized culture (usually U.S. culture) replaces the genuine local culture. To protect local culture, governments may seek to reduce the influence of outside cultural “imperialism” in several ways: (1) providing an alternative, subsidizing local cultural products, (3) banning outside cultural products, and (4) setting quotas.

Examples of this cultural protectionism can be seen in France and China, where government regulation has restricted the importation of American music and films. Canada is an example of a country that has chosen to not only restrict U.S. media content, but to also offer cultural subsidies to local artisans, including musicians, to develop their craft and products. The United Kingdom is an example of a country that has chosen to offer a government-sponsored alternative to “Hollywood” media by subsidizing the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). Their stated purpose is “to enrich people’s lives with great programmes and services that inform, educate and entertain” (BBC Website, 2004). The most common forms of cultural protectionism are quotas and censorship.

Many nations have imposed quotas or trade barriers on the amount of cultural product imported into their country. Some examples are included in Table 16.7. All are done to preserve the local culture and local cultural industries.

Censorship is imposed to protect the moral and cultural values of a society. Censorship may include imported goods, but may also apply to entertainment produced locally. There are examples of censorship in the United States, stemming from public protests over broadcast material deemed immoral or indecent by public standards. Public outcry over the 2004 Super Bowl halftime show, in which Janet Jackson had a breast exposed, lead to an increase in fines imposed by the Federal Communications Commission for indecency on the public airwaves.

The United States is considered generally more liberal than some other countries in allowing for free expression of ideas. In many parts of the Middle East, North Africa and China, censorship of music is common (Cloonan, M and Reebee G., 2003). In 1996, officials in Iran arrested 28 teenagers for possessing “obscene” CDs and cassettes. In 1997, South Korean radio station KBS banned teen pop music because of the clothing styles worn by the entertainers. In 2003, heavy metal fans in Morocco were jailed for “acts capable of undermining the faith of a Muslim” and “possessing objects, which infringe morals” (Index Online, March 7, 2003).

China is one of the most heavily regulated countries with regard to music censorship (Orban, M., 2003). Nothing can be produced or distributed without permission from Chinese government authorities. Restrictions are placed on all materials that”… are against the basic principles of the Constitution … that advocate obscenity, superstition or play-up violence or impair social morals and cultural traditions, and those that insult or defame others” (Brenneman, E. S., 2003).

Opportunities for growth in the international recording industry are coming from two areas: New markets and new technologies. This growth will be fueled by a reduction in trade barriers, improved economic conditions, the availability of new distribution channels, and continued adoption of next-generation technologies (Pricewaterhouse Coopers, 2004). Bessman claims that “by 2006 the ‘experimental phase’ of digital music services development will be over, with the subscription models in place …” (Bessman, J., 2002).

Informa Media Group predicts a return to growth in the music industry in 2005 and expects that by 2008, the value of global sales will rise to U.S. $32 billion (Press Release, 2005).

Asia/Pacific is emerging as the key area of growth in the entertainment and media industries, fueled mainly by China and India, both of which are investing in new communication technologies and media infrastructure as well as opening up their markets to international goods. China, with its population of 1.29 billion, and India, with its population of over one billion, offer the potential for growth and both have a low penetration of media hardware at this point in time. Efforts to stem piracy combined with heavy investments in media industries will drive growth in the region. Compact disc hardware penetration in India was reported at 9% for 2003, with no measured penetration in China. Mobile phone penetration was at 17% in China, and 1% in India in 2003.

The recording industry will experience a major shift in the way music is distributed, especially in new markets that do not possess a current infrastructure for the distribution of physical CDs. Growth in these areas is expected to be fueled by the expansion of broadband Internet access and wireless communications. Between 2003 and 2008, the number of broadband households is expected to grow at 31.3% compound annual growth rate.

Music-to-mobile services are already big business in Japan, South Korea and Taiwan, and parts of Europe. Music-to-mobile is defined as the downloading of music—from ringtones to full master recordings—into handheld mobile devices. These devices are third-generation cell phones (3G) capable of providing entertainment in addition to phone services. In South Korea, music-to-mobile sales generated U.S. $29 million for record companies in 2003. As bandwidth increases, more companies will be offering mobile jukebox services. The United States and China represent the largest potential markets. Since the United States dominates in global music sales, growth is anticipated when wireless infrastructure catches up to the European and Asian levels. China represents the potential for growth due to its massive population, increasing disposable income and a vast young consumer base (IFPI, 2004b).

GATT

From 1948 through 1994, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) provided the rules for much of world trade and handled issues dealing with international commerce. Members of GATT pledged to work together to reduce tariffs and other barriers to international trade, and to eliminate discriminatory treatment in international commerce. The GATT was designed as an interim measure pending the creation of a specialized institution to handle the trade side of international economic cooperation. The first attempt, the International Trade Organization (ITO), failed to materialize when the U.S. Congress refused to ratify the treaty. However, the GATT remained in effect and was the only multilateral instrument governing international trade from 1948 until the World Trade Organization was established in 1995.

WTO

The World Trade Organization (WTO) was established as a result of the final round of the (GATT) negotiations, called the Uruguay Round. The WTO is responsible for monitoring international trade policies, handling trade disputes, and enforcing the GATT agreements (www.encyclopedia.com, 2004). The WTO website describes their mission as:

“At the heart of the system—known as the multilateral trading system—are the WTO’s agreements, negotiated and signed by a large majority of the world’s trading nations, and ratified in their parliaments. These agreements are the legal ground-rules for international commerce. Essentially, they are contracts, guaranteeing member countries important trade rights. They also bind governments to keep their trade policies within agreed limits to everybody’s benefit” (World Trade Organization, 2004).

TRIPS

Even before the WTO was formally operational, the Uruguay Round of the GATT negotiations produced the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), negotiated from 1986–94. This agreement introduced intellectual property rules into the multilateral trading system for the first time, and addressed protection of copyright ownership of recorded music. The agreement establishes a minimum amount of copyright protection for creative works and specifies how countries should protect and enforce these rights.

There are several avenues for marketing recorded music overseas: (1) the major labels tap their affiliates in the region; (2) indie labels license the recording to local labels in the territories of interest; (3) products manufactured in the United States are exported through a foreign distributor; (4) digital delivery to the consumer via the Internet. In all cases, international touring schedules are generally set up to coincide with the release of the album in that territory.

The major labels rely on their branch (affiliate) offices around the world to promote products deemed profitable in those markets. The majors have the lion’s share of the market in most countries, with a viable recording industry as indicated in Table 16.8.

|

Table 16.8 Combined market share of majors |

|

Territory |

Combined market share of majors |

North America |

81.8% |

Latin America |

74.0% |

Europe |

80.6% |

Asia |

62.1% |

Australasia |

82.5% |

Africa |

66.0% |

WORLD |

74.7% |

|

Source: IFPI |

Marketing through an affiliate

Each regional affiliate of a major label operates independently for the most part, and each branch is responsible for its own marketing. Affiliates generally have the option to accept or decline an opportunity to release a record from an affiliate in another region. For example, if a U.S. branch wants affiliates in other territories to take on one of their releases, they would use a product presentation as an opportunity to pitch the project to affiliates in the targeted territories. If the artist is a major star with international appeal, an international release is customary. If the artist is mid-level or emerging, the U.S. branch may have to convince the affiliates that they should take on the release, even to the extent of paying a portion of the artist’s travel expenses. They would also want to demonstrate the marketability of this release.

International affiliates of a major label will gather periodically for product meetings. At these meetings, product presentations by each affiliate feature the artists that they think are most appropriate for international release. The other affiliates at the meeting then take this under consideration, keeping in mind similar acts that they might be working, and consumer demand in their territory.

The potential releases are then prioritized by label, by album and by single. Having a great single can move an album up the priority list. If the label doing the pitching does not succeed with their own affiliates, they may consider contracting with an entity outside of the major label system for distribution in that region, but the affiliates get first refusal.

Touring has an impact on the decisions of whether to take on a project. An artist, their manager, and their booking agent may work with their label to coordinate an overseas release with a concert tour in that region. At times, a label’s clout with one artist may help influence an affiliate to take on projects from other artists on the label. For instance, if an affiliate in Europe wanted to handle the release of a major U.S. artist, that artist’s U.S. label may request or require that the affiliate handle other acts on the label as well. An artist’s contract with their label may also guarantee that the record will be released internationally. If that artist is still developing, the label may scramble to find foreign territories interested in the release. For a major act, a coordinated worldwide release is normal, with all other affiliates onboard to take advantage of a global marketing campaign. On occasion, a U.S. artist will be released initially overseas to “test market” the artist before investing in a U.S. release.

For the international release of Creed’s first album, Jed Hilly, who served as Vice President Marketing Services, Sony Music International, New York, had this to say (Jed Hilly, personal interview):

“When the Creed/Wind-Up deal was announced, I worked with the Wind-Up people and we orchestrated an event. We invited marketing representatives from all over the world, about 20-something people came. Japan, U.K., France—we had guests from all over the world, to Orlando, Florida. We had an afternoon performance where we rented a suite at the local Marriott. We had Julia Darling and Stretch Princess do acoustic sets and then we went to the House of Blues later that night and Finger Eleven warmed up for Creed, for about 2,000 people. So everyone got to go experience that, meet the band members and label personnel. We did that in November and the official Wind-Up launch [internationally] was in January. We had to do this to get people on board.” (Jed Hilly)

Once Creed was established in the marketplace, subsequent albums were released with an international plan in place.

Indie labels and international markets

Independent labels must work through arrangements made with labels or distributors in other territories. Arrangements with local labels usually involve licensing and arrangements with distributors involved in the transshipment of products created in the home territory. Again, touring plays a major factor in the success of indie label artists overseas.

Licensing was discussed in an earlier section dealing with parallel imports. The label originally releasing an album licenses a label in a foreign territory to release the recording in that territory. The licensor (original label) provides the licensee with a master recording and all related artwork in exchange for a fee and a percentage of sales. The licensee is responsible for manufacturing, distribution and marketing in the designated territory. Compensation is paid to the licensor at generally 8–17% of the local retail list price, or computed as a percentage of published price to dealer (PPD), or wholesale price (Lathrop, T. and Pettigrew, J. Jr., 1999).

When licensing is done, indie labels give up much of the potential for profit, as well as control over manufacturing, sales and marketing. Generally, the licensor does not place requirements or restrictions on how a record is to be marketed. However, requirements may include the quantity of product for which royalties will be paid.

Some indie labels prefer to avoid licensing if they have the resources to engage in marketing activities on their own or with the assistance of a local distributor. It allows them to gain more control over the marketing and distribution process. However, this may vary depending on the territory. One independent label, Compass records, prefers to use licensing arrangements in most of Asia, while relying on local distributors in other territories (transshipments) (Thad Keim, personal interview).

In this situation, finished recordings are rerouted or exported to a foreign distributor. For the importing territory, they are not considered parallel imports unless a locally licensed version is also available. Indie labels that engage in using foreign distributors must work hard to promote the recordings in those regions. They must contact local press, and generally coordinate closely with any touring arrangements. It is also wise to price the product competitively with local pricing, rather than pricing as an “import.” Indie labels may use different distributors for each territory and perhaps even different distributors within a territory, dependent upon the music genres they are involved with.

The timing of the release date must be taken into consideration for each territory. An artist who does well in Australia may want a fourth-quarter release date. The same artist may not be as well known in the U.S., and may require a release date in the first quarter of the following year.

“When Compass released The Waifs, ‘A Brief History …’ CD in January 2005, it followed the release date in their native Australia by almost three months. While the ideal situation would have been a simultaneous release schedule, it’s very difficult for an independent label to release a CD in the U.S. during November (and remain competitive) with all the major labels, hit product being released during 4th quarter. Since among other things, marketing costs at retail average three times higher during this period, we decided to wait until January for the U.S. release. The same restrictions don’t apply to The Waifs in Australia, as they are a platinum selling act down there.” (Thad Keim, Vice President, Sales & Marketing, Compass Records)

Timing is also important to minimize the potential impact of parallel imports.

“When Compass set up Paul Brady’s 2005 release, for the U.S. and Europe, we were in a position where our release dates in certain territories had to be within a 1–2 week window of one another or we would run the risk of exports from one territory making their way into another and upsetting the domestic release. Exports from the U.S. were of the most concern because the dollar is rather weak against the Euro and Pound right now. So in this case, the risk of exports did have some influence on setting our release dates.” (Thad Keim)

Internet sales and distribution

The Internet has created opportunities for smaller record labels to compete internationally by offering products for sale through their website. Such sales fall into two categories: (1) the shipment of physical products to global consumers, and (2) the commercial sale of downloads. Target marketing is no longer limited to geographic segmentation, as the Internet has eliminated geographic barriers to marketing, sales and distribution. This is beginning to complicate the issue of territorial rights, differential pricing and staggered release dates.

The basic marketing aspects of radio, press, tour support, retail promotion, and video are utilized to market overseas, but the relative importance of each may vary from country to country. Many foreign countries have a different radio industry structure from what has been established in the United States. Government-run radio, such as the BBC, dominates many foreign countries that have only recently introduced privately-owned radio networks. MTV is popular in Europe and Asia and has been proven successful in marketing, but is beyond the reach of all but the majors. Tour support becomes a more important aspect of many of the U.S. acts promoted overseas.

Music genre classifications vary from country-to-country, and may be vastly different from what we are used to in the U.S. For example, in Europe, country music encompasses folk and Americana.

It is precisely because of these vagaries that marketing in a particular region should be left up to that local affiliate or a distributor with the resources to assist in marketing. They know best what will work in their market. The pre-release set up must be done up to two months in advance of the release in order to get press coverage such as magazine covers and media reviews at the time of the release. That can become difficult if the materials are not ready, or the label is not willing to release these materials (including an advance copy of the album) overseas in advance of the album release.

With a new artist, an overseas release usually comes after some success with sales in the United States demonstrating the profitability of the recording. It also allows the artist to wrap-up a U.S. tour before going overseas to support the release with the international tour. For an established artist, a worldwide release date is common to reduce the likelihood of parallel imports and piracy.

The international recording industry faces many of the same challenges that face the RIAA and the U.S. recording industry, and add to that the increased level of piracy and complications stemming from international trade. The industry is monitored by the IFPI, which provides data on recorded music sales and economic climates of the various member nations. The industry numbers in this chapter were the most current available at the time of printing. The IFPI releases annual global statistics in the fall of each year. By applying the concepts outlined in this chapter to economic indicators in subsequent years, the student of the international recording industry can continue to gain insight in the complex factors influencing international record sales.

Opportunities for growth in the recorded music industry will mainly stem from new technologies and the development of new markets as global trade becomes more commonplace. Overseas marketing can be lucrative for the home label and the artist since the expenses associated with pre-production (mastering, video production, and so forth) and marketing are picked up by the overseas affiliate or business partner, and risk is minimal for the home label.

“This is a global marketplace and you can’t approach a pop record and just be thinking about America, because music is one of America’s greatest exports. It’s the global perspective.” (Jed Hilly)

Censorship – The process of banning or deleting content considered unsuitable for reading or viewing.

Cultural imperialism – The extension of rule or influence by one society over another.

Emerging markets – Countries that are still growing their industrial sector, moving from predominantly agricultural products to manufacturing.

General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) – Established in 1948 between member countries to facilitate international trade.

International Federation of Phonographic Industries (IFPI) – The global trade organization for recorded music industries.

Licensing of recordings – The original record label grants a foreign record label a license to issue an artist’s recording in its local or regional territory.

Market saturation – The quantity of products in use in the market place is close to or at its maximum.

Mature market – A market that has reached a state of equilibrium marked by the absence of significant growth or innovation.

Oligopoly – A market dominated by a small number of participants who are able to collectively exert control over supply and market prices.

Parallel imports – The importing of copyright goods into a country that were lawfully made in a foreign country, without obtaining permission of the holder of the copyright for those goods in the recipient country.

Super audio compact disc (SACD) – A Sony formatted compact disc.

Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) – An agreement that establishes a minimum amount of copyright protection for creative works and specifies how countries should protect and enforce these rights.

Transshipment – The act of sending an exported product through an intermediary before routing it to the country intended to be its final destination.

World Trade Organization (WTO) – An organization responsible for monitoring international trade policies, handling trade disputes, and enforcing the GATT agreements.

Bibliography

BBC Website (2004). http://www.bbc.co.uk/info/purpose/.

Bessman, J. (2002). Slow Global Music Growth Predicted, http://www.bandname.com/magazine/articles/display_article.asp?article=slow.

Brenneman, E. S. (2003). China: Culture, Legislation and Censorship. Excerpts from Chinese Cultural Laws Regulations and Institutions, http://www.freemuse.org/sw5220.asp.

Broward Daily Business Review (2004). Annual Global Sales of Recorded Music Fall Again, Broward Daily Business Review, 45, (84). http://www.web.lexis-nexis.com/.

Burnett, R. (1996). The Global Jukebox, New York: Routledge.

Cloonan, M. and Reebee G. (2003). In Cloonan, M and Reebee G. (ed) Policing Pop, Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

IFPI press release (March 22, 2005). Global music retail sales, including digital, flat in 2004, www.ifpi.com.

IFPI (2004a). The Industry in Numbers, International Federation of the Phonographic Industry.

IFPI (2004b). The Recording Industry in Numbers annual report, www.ifpi.org.

Index Online (March 7, 2003). Report: Morocco: Judge jails Moroccan heavy metal fans, http://www.indexonline.org/indexindex/20030307_morocco.html.

Lathrop, T. and Pettigrew, J. Jr. (1999). This Business of Music Marketing and Promotion, New York: BPI Publications.

Lathrop, T. and Pettigrew, J. Jr. (1999). This Business of Music Marketing and Promotion, New York: BPI Publications.

Orban, M. (2003). Censorship in Music, http://www.bgsu.edu/departments/tcom/faculty/ha/sp2003/gp9/docs/TCOMPAPERONCENSORSHIP.doc.

Press Release (2005). No Growth in Global Music Sales Before 2005, http://www.the-infoshop.com/press/fi16775_en.shtml.

PricewaterhouseCoopers (2004). http://www.pwcglobal.com/extweb/ncpressrelease.nsf/docid/418FBBF773CAD0A4CA256ECA002F4489.

The Foreign Exchange Market (2004). http://www.worldgameofeconomics.com/exchangerates.htm.

Throsby, D. (2002). The Music Industry in the New Millennium: Global and Local Perspectives, Paper prepared for the Global Alliance for Cultural Diversity; Division of Arts and Cultural Enterprise, UNESCO, Paris.

Vaknin, S. (2001). The Benefit of Oligopolies. http://www/suite101.com/files/topics/6514/files/capitalism.rtf.

www.encyclopedia.com (2004). www.encyclopedia.com. World Trade Organization (2004). http://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/whatis_e/inbrief_e/inbr00_e.htm.