8 Economic growth, "globalization," and labor power

Introduction

The key point made in this chapter is that economic globalization can enhance labor market capabilities and thereby improve the standard of socio-economic well-being of workers. Moreover, increasing material benefits to labor need not have any negative competitive consequences; most probably positively affecting productivity. Thus, I argue that the anti-globalization-trade-market hypothesis is fundamentally flawed. A contentious populist belief, with much academic weight behind it, contends that increasing international trade and its most recent historical rhetorical manifestation, “globalization,” has damaging affects upon the economic welfare of the vast majority of the world’s population. Such negative effects are an inevitable consequence, it appears, of capitalism, especially that which embraces globalization. Globalization implies a race to the bottom and a shift of resources from the less developed to the more developed economies. It is either implicitly or explicitly assumed that globalization is part and parcel of a zero-sum game—there can only be winners and losers and most folk in this world end up with the short end of the stick.

The negative view of globalization is held by advocates and academics across the political spectrum, but especially at the extremes. It is fundamentally nested in conventional economic theory which assumes that higher benefits to labor, improved working conditions, greener economies, “ethical” production, and the like yield higher unit production costs and as such are not sustainable in an increasingly competitive world economy (see Chapters 2 and 3). Economic theory either explicitly or implicitly has a profound effect on the direction of public advocacy and public policy. For some, one must adjust economies and the institutions in which they are embedded to allow for economies to remain competitive, with the expectation that some time in the future the erstwhile benefits of globalization will trickle down. For others, on both the right and the left, the barricades must be raised against the onslaught of the flood waters of globalization and the socio-economic devastation that it is predicted, on the basis of theory, to wreak havoc on the majority of the population.

Building upon my research in behavioral economics (Altman 1992b, 1996, 2000b, 2000c, 2001d, 2001b, 2002, 2004b, 2005b; see also Chapters 2 and 3), on x-efficiency theory and endogenous technical change, and on a better understanding of the role of institutions in determining labor market outcomes, I argue that globalization in terms of increasing trade has the capacity to enhance the bargaining power of labor (labor market capabilities), and thereby economic efficiency (in terms of x-efficiency) and the rate of technological change with significant resulting benefits flowing to labor.1 Power (Altman 2000c, 2005b; Rothschild 2002) is a key variable in this narrative, as actualized through labor market capabilities. In the first instance, enhanced labor market capabilities increase real wages and other pecuniary and nonpecuniary rewards to labor (hours of work, health and safety, etc.) as well as providing the necessary pressures to enhance an economy’s economic efficiency.

By enhancing the rate of technological change and by inducing technological change of a dominant type—one which must be adopted by both the high and low wage economies, subject to competitive pressures—tight labor markets in one domain yield positive externalities in another. This serves to increase the level of workers’ well-being in the trigger (tight labor market) economies as well as in those economies where labor’s bargaining power is relatively weak. Once the forces of globalization serve to increase the rate of labor compensation this creates a degree of stability to this higher rate due to the opportunity cost of ratcheting downward the rate of labor compensation. This introduces a degree of path dependency to labor market improvements engendered through globalization.

Tight labor markets can be regarded as a key capability allowing workers (and peasants) to improve their welfare. That which serves to tighten labor markets, ceteris paribus, serves to enhance this capability. Labor market capabilities are enhanced by the existence and enforcement of labor rights. Globalization can have such positive effects on labor’s capabilities only if the institutional infrastructure is present which allows labor to take advantage of tightened labor market conditions induced by enhanced trade which is often a corollary of globalization. This points to the importance of institutional variables in determining the manner in which globalization impacts on labor market capabilities. Thus labor market outcomes are enhanced (higher wages, better working conditions, etc.) for any demand for labor, given the presence and enforcement of basic labor rights inclusive of the existence of politically free labor (workers own their own labor power), right to mobility, right to collectively organize and bargain with firm owners inclusive of the state–public enterprises.2 These can be referred to as basic labor market human rights. Given such fundamental or core labor rights, within the context of a competitive market economy, where property rights are also guaranteed and enforced, workers can benefit significantly from economic globalization. Absent such rights the gains to labor would be limited. However, economic globalization can be expected to enhance the level of workers’ socio-economic well-being, ceteris paribus.

The conventional literature pro and con globalization pays little heed to the institutional parameters that filter the socio-economic effects which economic globalization might have. The conventional literature also pays little heed to the dynamic efficiency effects which globalization has when it positively affects labor market outcomes—x-efficiency and endogenous technical change. It is the unintended consequence of globalization that labor market capabilities are enhanced. Corporations need only pursue increasing international trade simply to improve their bottom-line. There need be no conscious intent by corporations to proactively support the enhancement of labor rights and freedoms. This does not vitiate the fact that, ceteris paribus, increasing trade serves to enhance the bargaining power of labor and thereby the level of socio-economic well-being of workers. Self-interested corporate behavior can yield positive social results if institutions are not adjusted to neutralize any market generated increases in the bargaining power of labor. If, for example, in the face of increasing globalization, the state weakens the capacity of workers and peasants to bargain collectively or reduces or eliminates traditional social benefits to labor, such as unemployment insurance or pensions, labor’s bargaining power is weakened. This would also be the case if, for example, the state introduced policies which limits the mobility of labor.

Introducing institutional variables into an analysis of globalization, especially that of labor market capabilities (which relate to the issue of relative bargaining power amongst economic agents), helps to explain some fundamental stylized facts of the contemporary world economy. These facts suggest that economic globalization is strongly correlated with improving workers’ level of socioeconomic well-being where this effect varies greatly across economies. This variation appears strongly correlated with the extent of labor market capabilities. This suggests that if one’s objective is to improve the overall level of workers’ socio-economic well-being, increasing economic globalization plus enhancing labor market capabilities in the context of a market economy would be an important means toward realizing such a goal. It is important to emphasize that this was key to Adam Smith’s (1937) grand schema for improving the socio-economic well-being of humanity in spite of the self-interested nature of humanity, especially that of the “masters.” This modeling is distinct from efforts to explain the differential impact of globalization largely in terms of differential protection of private property rights or differentials in competitive pressure. While the latter two variables can be of critical importance for globalization or trade induced growth to take place, the labor capabilities variable also plays a penultimate role in the process.

This argument in no way denies the socio-economic hardship which might arise from economic restructuring which might be engendered by globalization. However, one must recognize that such restructuring would take place independent of globalization as demand restructures and as technological change proceeds. Economic policies can be instituted which protect workers from such hardship for which they are in no way responsible—job retraining, for example. However, the counterfactual argument that need be asked with regards to economic globalization is: would workers and peasants be worse off without it? Is the economic problem with regards to the level of socio-economic well-being resolved by isolating economies from the effects of increasing trade or by building appropriate institutions which filter the effects which increasing international trade has on labor?

Some stylized facts

The most recent wave of globalization, in terms of increasing international trade, has been marked with significant improvements to the well-being of the general populace, however measured. Thus in terms of per capita real GNP, absolute levels of poverty, and of the more comprehensive United Nation’s Human Development Index (HDI), which is a weighted combination of per capita income, mortality, life expectancy measures, and education levels, socioeconomic well-being has gone up throughout the world, both amongst developed and less developed economies. I refer to a few selected vignettes from the World Bank’s World Development Report and the United Nation’s Human Development Report. The evidence clearly suggests that there is both good and bad news with regards to the impact of globalization, with the balance clearly in favor of the good news in terms of the measures of well-being counted by the World Bank and the United Nations. Institutional variables play a critical role in determining the impact of globalization. The behavioral model presented below helps explain these stylized facts.

From the World Bank's World Development Report

- There have been measured improvements in well- being during a period of increasing globalization:

over the past 30 years world population also rose by 2 billion. And this growth was accompanied by considerable progress in improving human well-being as measured by human development indicators. Average income per capita (population weighted in 1995 dollars) in developing countries grew from $989 in 1980 to $1,354 in 2000. Infant mortality was cut in half, from 107 per 1,000 live births to 58, as was adult illiteracy, from 47 to 25 percent.

(World Bank 2003, p. 1)

- There has been a significant drop in poverty rates (of people living on less than $1 per day) and in the number of absolute poor in spite of the large population increase:

Even the absolute number of very poor people declined between 1980 and 1998 by at least 200 million, to almost 1.2 billion in 1998. The decrease was primarily due to the decline in the number of very poor people in China as a result of its strong growth from 1980 onward.

(World Bank 2003, p. 2)

According to the World Development Report, 2006 (World Bank 2006, p. 66), the decline in the number of absolute poor has been even more dramatic, falling by about 400 million people from 1981 to 2001. Apart from China significant improvements have also been made in India, Bangladesh, and Pakistan, in other words in many of the world’s most populous countries.

- Poverty reduction has been significant even in regions which have been previously problematic in terms of poverty reduction. The one clear exception to this is Sub- Saharan Africa; but this cannot be attributed to increasing economic globalization:

Since 1993, there have also been encouraging signs of renewed poverty reduction in India. Sub-Saharan Africa, by contrast, has seen its number of very poor people increase steadily. Yet in 1998, despite the decline in Asia and the increase in Sub-Saharan Africa, East Asia and South Asia still accounted for two-thirds of the world’s very poor people, and Sub- Saharan Africa for one quarter.

(World Bank 2003, p. 2)

In Sub- Saharan Africa, the number of people living in absolute poverty increased from 160 to 313 million from 1981 to 2001 (World Bank 2006, p. 66). But globalization cannot be causally linked to the deep rooted problems facing Sub-Saharan Africa, a region plagued by civil unrest, civil wars, and AIDS.

- According to the World Development Report, 2006 (p. 88), economic growth, much of this securing through increases in economic globalization, is largely responsible for the significant increases in real income and consumption across the distribution of income and, thereby, a major instrument in poverty reduction in the last twenty years of the twentieth century. Ceteris paribus, during the 1981–2001 period, an increase of 1 percent in average income, reduced the poverty rate by 2.4 percentage points, although there is much variation around the mean. This being said, it is concluded:

This powerful association between economic growth and poverty reduction is one of the central stylized facts of development economics. Its qualitative nature has long been understood, and it has recently been quantified. . . . Indeed, the growth-poverty relationship is probably more powerful than surprising: it merely reflects the fact that, on average, the growth in the incomes of the poor is similar to the growth of mean incomes. Put differently: aggregate economic growth is, on average, distribution neutral.

(World Bank 2006, p. 88)

- But the World Bank recognizes that this important average relationship is filtered by institutional variables of which the World Bank places great emphasis upon income distribution:

About half the total variation in poverty reduction is accounted for by economic growth. The other half must reflect changes in the underlying distribution of relative incomes. This happens because the incidence of economic growth (its distributional pattern) can vary dramatically across countries. Two countries with similar rates of growth in mean incomes can have very different growth profiles across the population. As one would expect, reductions in inequality at a given growth rate add a “redistribution component” to the “growth component,” leading to faster overall poverty reduction.

(World Bank 2006, p. 88)

Therefore, growth itself, and trade induced growth, are not sufficient for poverty reduction. Much depends on what happens to income distribution when growth takes place.

From the United Nations Human Development Report

The Human Development Report measures and discusses well-being in a manner which incorporates per capita income, education, and mortality. It only confirms what the World Development Reports articulate using different methodologies. For example, Human Development Report, 2003:

Though average incomes have risen and fallen over time, human development has historically shown sustained improvement, especially when measured by the HDI [Human Development Index]. But as noted, the 1990s saw unprecedented stagnation and deterioration, with the HDI falling in 21 countries. Many of these countries have insufficient data to calculate the HDI before 1990, so there is no way of knowing if their HDIs also fell in the 1980s. Of the 114 countries with data since 1980, only 4 saw their HDIs decline in the 1980s—while 15 saw declines in the 1990s (Table 2.1). Much of the decline in the 1990s can be traced to the spread of HIV/AIDS, which lowered life expectancies, and to a collapse in incomes, particularly in the CIS.

(United Nations 2003, p. 40)

The Human Development Report, 2005 reiterates these findings:

On average, people in developing countries are healthier, better educated and less impoverished—and they are more likely to live in a multiparty democracy. Since 1990 life expectancy in developing countries has increased by 2 years. There are 3 million fewer child deaths annually and 30 million fewer children out of school. More than 130 million people have escaped extreme poverty. These human development gains should not be underestimated.

(United Nations 2005, pp. 3, 19–23)

The Human Development Report, 2003 (p. 2), finds negative development in terms of an increase in income inequality measured by the absolute income gap between countries. This coincided with an increase in real income in almost all countries, inclusive of those with the largest populations:

The average income in the richest 20 countries is now 37 times that in the poorest. This ratio has doubled in the past 40 years, mainly because of lack of growth in the poorest countries. Similar increases in inequality are found within many (but not all) countries.

(p. 3)

The net effect

The bad news articulated both by the World Development Report and by the Human Development Report does not preclude or override the good news articulated in both reports. The net effect of growth and increasing international trade on human development, poverty reduction, and related indicators, have been positive (see also Bhagwati 2000; Davies and Quinlivan 2006; Irwin 2002; Wolf 2004). The good news could have been even better—much depends on the institutions in place. However, the fact that income divergence has taken place big time and that some countries’ positions have deteriorated in both relative and absolute terms has been wrongly and misleadingly translated into an immiseration thesis. Globalization has not been shown to be empirically the harbinger of global immiseration; just the opposite appears to be the case. But the overall impact of globalization upon socio-economic well-being is significantly affected by the institutions in place. Markets represent only one blade of one’s analytical scissors, institutions represent the other.

Adam Smith and globalization

Given that much populist and academic rhetoric suggests that (market-contextualized) globalization can be damaging to labor or, alternatively, that the benefits of globalization accrue to labor rather automatically, it is pertinent to note that Adam Smith’s narrative departs dramatically from such perspectives. For Smith more international trade and freer trade contained only the potential for dramatically improving the socio-economic well-being of the general populace. Smith had no conception of invisible hands willy-nilly transforming international free trade into an engine fueling welfare improvements for the general populace. Critical to this chapter is the relationship between increasing trade and the material well-being of labor. More specifically, this chapter is concerned with the direction of causality between increasing trade and labor benefits, as mediated by labor market institutions, and between increases in labor compensation and increases in the wealth of nations. Some of the salient points made by Smith in the Wealth of Nations (1937, Book I, Part VIII, “Of the wages of labor”) with regards to this discourse on globalization are:

- Increasing intranational and international trade is key to improving the socio-economic well-being of workers. The freer this trade the more efficient an engine of growth will it be.

- Generalized improvements in the well-being of workers, inclusive of increasing real wages should be welcome.

- The organization of labor is important to workers achieving such improvements.

- Such improvements serve to increase the efficiency of labor.

Smith argues that laborers have an advantage on labor markets only under very specific circumstances:

There are certain circumstances, however, which sometimes give the labourers an advantage, and enable them to raise their wages considerably above this rate [bare subsistence]; evidently the lowest which is consistent with common humanity. When in any country the demand for those who live by wages, labourers, journeymen, servants of every kind, is continually increasing; when every year furnishes employment for a greater number than had been employed the year before, the workmen have no occasion to combine in order to raise their wages. The scarcity of hands occasions a competition among masters, who bid against one another, in order to get workmen, and thus voluntarily break through the natural combination of masters not to raise wages.

(Smith 1937, p. 68)

Smith emphasizes that it is not the absolute wealth of nations that determines the “bargaining power” of labor. It is rather the extent to which an economy grows that is critical. Smith writes:

It is not the actual greatness of national wealth, but its continual increase, which occasions a rise in the wages of labour. It is not, accordingly, in the richest countries, but in the most thriving, or in those which are growing rich the fastest, that the wages of labour are highest. England is certainly, in the present times, a much richer country than any part of North America. The wages of labour, however, are much higher in North America than in any part of England.

(p. 69)

A growing economy is relatively much more beneficial to labor than a stagnant one. Smith:

The liberal reward of labour, therefore, as it is the necessary effect, so it is the natural symptom of increasing national wealth. The scanty maintenance of the labouring poor, on the other hand, is the natural symptom that things are at a stand, and their starving condition that they are going fast backwards.

(p. 72)

Smith argues that there is both an ethical and economic reason for favoring improvements in the material reward to labor. Ethically, those who play a vital role in generating the wealth of nations should reap some of the fruits of their labor. Smith argues:

Is this improvement in the circumstances of the lower ranks of the people to be regarded as an advantage or as an inconveniency to the society? The answer seems at first sight abundantly plain. Servants, labourers and workmen of different kinds, make up the far greater part of every great political society. But what improves the circumstances of the greater part can never be regarded as an inconveniency to the whole. No society can surely be flourishing and happy, of which the far greater part of the members are poor and miserable. It is but equity, besides, that they who feed, cloath and lodge the whole body of the people, should have such a share of the produce of their own labour as to be themselves tolerably well fed, clothed and lodged.

(p. 78)

But increasing the material rewards to labor also contributes toward making them more productive. Smith’s insights are clear forerunners to efficiency wage theory. Smith makes the case that:

The liberal reward of labour, as it encourages the propagation, so it increases the industry of the common people. The wages of labour are the encouragement of industry, which, like every other human quality, improves in proportion to the encouragement it receives. A plentiful subsistence increases the bodily strength of the labourer, and the comfortable hope of bettering his condition, and of ending his days perhaps in ease and plenty, animates him to exert that strength to the utmost. Where wages are high, accordingly, we shall always find the workmen more active, diligent, and expeditious, than where they are low.

(p. 81)

However, the rewards to labor are mediated by the bargaining power of labor relative to that of their masters. He viewed that latter as predisposed to minimize wages and that objective would be realized unless workers are able to organize to improve their level of material compensation. Smith argues:

What are the common wages of labour, depends every where upon the contract usually made between those two parties, whose interests are by no means the same. The workmen desire to get as much, the masters to give as little as possible. The former are disposed to combine in order to raise, the latter in order to lower the wages of labour.

(p. 66)

In the absence of institutional intervention, masters have a “natural” bargaining advantage over labor. Smith maintains:

It is not, however, difficult to foresee which of the two parties must, upon all ordinary occasions, have the advantage in the dispute, and force the other into a compliance with their terms. The masters, being fewer in number, can combine much more easily; and the law, besides, authorises, or at least does not prohibit their combinations, while it prohibits those of the workmen. We have no acts of parliament against combining to lower the price of work; but many against combining to raise it. In all such disputes the masters can hold out much longer. A landlord, a farmer, a master, manufacturer, or merchant, though they did not employ a single workman could generally live a year or two upon the stocks which they have already acquired.

(p. 66)

Smith further argues that, in his time, it was combinations by masters that was sanctioned and that of workers deplored, often with the backing of the force of law:

We rarely hear, it has been said, of the combinations of masters; though frequently of those of workmen. But whoever imagines, upon this account, that masters rarely combine, is as ignorant of the world as of the subject. Masters are always and every where in a sort of tacit, but constant and uniform combination, not to raise the wages of labour above their actual rate. To violate this combination is every where a most unpopular action, and a sort of reproach to a master among his neighbours and equals. We seldom, indeed, hear of this combination, because it is the usual, and one may say, the natural state of things which nobody ever hears of. Masters too sometimes enter into particular combinations to sink the wages of labour even below this rate. These are always conducted with the utmost silence and secrecy, till the moment of execution, and when the workmen yield, as they sometimes do, without resistance, though severely felt by them, they are never heard of by other people.

(p. 66)

Workers attempt to counter the combinations of masters designed to lower their real wage or at times organize simply to improve their reward. But Smith is pessimistic of what workers could achieve given the advantages held by masters in the late nineteenth century:

Such combinations, however, are frequently resisted by a contrary defensive combination of the workmen; who sometimes too, without any provocation of this kind, combine of their own accord to raise the price of their labour. Their usual pretences are, sometimes the high price of provisions; sometimes the great profit which their masters make by their work. But whether their combinations be offensive or defensive, they are always abundantly heard of. In order to bring the point to a speedy decision, they have always recourse to the loudest clamour, and sometimes to the most shocking violence and outrage. They are desperate, and act with the folly and extravagance of desperate men, who must either starve, or frighten their masters into an immediate compliance with their demands. The masters upon these occasions are just as clamorous upon the other side, and never cease to call aloud for the assistance of the civil magistrate, and the rigorous execution of those laws which have been enacted with so much severity against the combinations of servants, labourers, and journeymen. The workmen, accordingly, very seldom derive any advantage from the violence of those tumultuous combinations, which, partly from the interposition of the civil magistrate, partly from the superior steadiness of the masters, partly from the necessity which the greater part of the workmen are under of submitting for the sake of present subsistence, generally end in nothing, but the punishment or ruin of the ringleaders.

(p. 67)

Given the institutional constraints faced by labor plus the limited resources at their disposal to maintain a prolonged “job action” against masters, Smith argues that the best opportunity for improving workers’ material welfare lies in tight labor market conditions against which masters can deploy few resources successfully given the existence of a relatively free market economy, wherein trade is free to flourish and labor is free to move to the master who offers the highest real wage.

For Adam Smith, although improvement in workers’ level of material well-being is to be welcomed and encouraged for both ethical and economic reasons, whether such improvements are actualized depends on the state of the market and the institutional relationships which filter the bargaining power of labor as affected by market forces. A more vibrant growing economy improves the bargaining power of labor (as we would say, ceteris paribus). However, the extent to which labor can take advantage of this situation depends on the contractual relationship between workers and masters. Of course, if institutions preclude workers’ capacity to bargain, this dramatically reduces the ability of workers to take advantage of a growing economy or to resist the negative effects which a stagnant economy might have upon their level of material well-being. Smith argues that the masters’ worldview, which is largely self-interested, drives them to do what they may to keep wages as low as possible over the long run. Tight labor markets make such endeavors difficult to realize when free labor markets exist. I argue, consistent with Smith, that institutional parameters which improve workers’ bargaining power have the same effect, especially when reinforced by tight labor markets.

Modeling the globalization and labor market effects: institutions matter

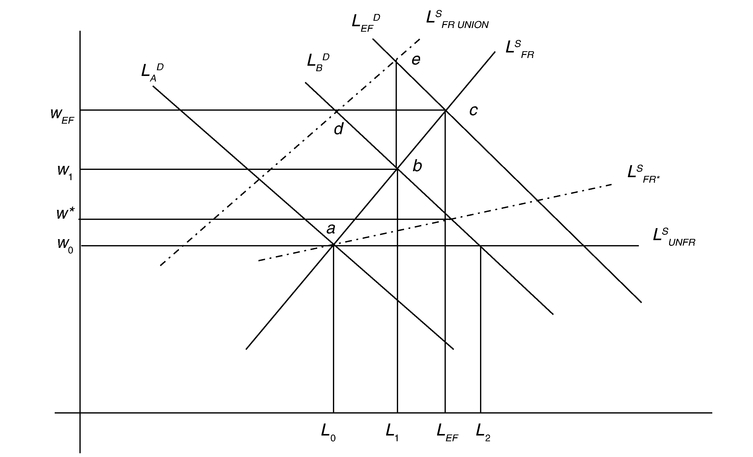

Using a conventional model of the labor market it is easy to see that, ceteris paribus, increasing trade, which serves to increase the demand for labor yields higher wages (Figure 8.1). In the first instance, increasing trade increases the demand for a firm’s output thereby, ceteris paribus, increasing the demand for labor. The size of the derived increase in the demand for labor is given by the elasticity of labor inputs to changes in output which is specified by the production function. Given a conventional labor supply curve of LSFR, if labor demand increases from LAD to LBD, ceteris paribus, the wage rate should increase. Given the increase in the demand for labor, the extent to which the wage rate is increased depends on the elasticity of labor supply. Wages increase to a greater extent for labor supply curve LSFR than for LSFR*, which is relatively more elastic (W0 to W1 compared to W0 to W*). The extent of the elasticity of labor is an empirical question and can be affected by institutional parameters.

At one extreme, when labor supply is perfectly elastic (LSUNFR), increases in labor demand yield no increases in the wage rate. Such a labor supply curve characterizes unfree labor markets wherein changes in labor demand have no impact on the price of labor. However, the basic conventional model assumes that wages are affected by changes in labor demand—the labor supply curve is positively sloped. Therefore, underlying the conventional model is the assumption of the prevalence of the institution of free labor wherein, at a minimum, labor is free and not impeded with regards to labor mobility between firms and between localities within a country. The conventional type model also assumes that the price of labor is set locally, regionally, or nationally. Thus, in terms of Figure 8.1, the main effect of increasing economic globalization is an unambiguous outward shift in the labor demand curve. Economic globalization need not

Figure 8.1 Globalization and labor markets.

have the effect of increasing the supply of labor, which might be anticipated when global markets are opening up. This would occur in a world of open borders where labor freely flows to wherever the pecuniary and non-pecuniary returns to labor are highest. In this case, the labor supply curve shifts outward, generating an offsetting effect upon the positive impact which increasing labor demand would otherwise have upon the rate of labor compensation. Such open borders typically do not exist. This has been especially true of the most recent century (O’Rourke and Williamson 1999). Even with relatively open labor markets the extent of this offset is contingent upon the type labor market institutions in place, where the latter can serve to neutralize the negative effects on labor compensation which increasing migration related labor supply might have. Advocates of low wage economies, however, would lobby for open borders for immigrants, with no accompanying countervailing labor market institutions, such as the right and reasonable capacity of workers and peasants to bargain collectively. If economic globalization yields greater increases in labor demand than in labor supply the net effect on wages would be positive. Moreover, open borders with regards to migration could only negatively affect high wage economies. Relatively low wage economies would be positively impacted, seeing their labor supply curves shift inwards as workers seek out opportunities in higher wage jurisdictions, while their labor demand curves shift outward with increasing economic globalization. Given the available evidence discussed and referenced in this chapter, the simplifying assumption of an outward shift in the (average) labor demand curve as a product of increasing economic globalization is a reasonable one for both low and high wage economies. However, it is important to note that immigration and labor market policy can significantly affect the position and elasticity of the labor demand curve as economic globalization takes on more force.

One reason for the introduction of institutions such as serfdom and slavery and for anti-union type interventions in the economy is to reduce the capacity of labor to take advantage of trade induced labor market capacities. Domar (1970) discusses and models slavery and serfdom as an intervention to neutralize if not reverse the expected outcome of relatively free labor markets. He does not differentiate, however, between different types of free labor economies and therefore between ones where workers are endowed with different levels of labor rights and benefits (unemployment insurance, for example). But the moral of his narrative has implications for both free and unfree labor markets. The critical point made by Domar is that as labor becomes increasingly scarce, landlords find it increasingly difficult to capture a desired share of a free peasant’s (tenant) income without institutional intervention. Domar causally relates the rise of serfdom and slavery with labor scarcity as both of these institutional forms are characterized by strictly limiting the mobility labor such that market forces are precluded from delivering the increasing rates of labor compensation which tight labor markets would otherwise generate. In the absence of labor scarcity, there is no economic imperative for such institutional intervention on the labor market. Failing such intervention, labor scarcity benefits labor—peasants in Domar’s discourse. Thus, the extent to which labor scarcity benefits labor is highly contingent upon institutional context.

Once institutions which filter out the effects of labor scarcity are in place, there need not be any economic incentive to remove such institutions even if free labor is more productive than unfree labor. Domar expects that free labor should be more productive than unfree labor for reasons of incentives, but also more expensive. Higher productivity might simply serve to cover increased wage costs. Thus institutions which regulate labor in favour of employers, such as serfdom and slavery, tend to be path dependent. With regards to the stability of such labor constraining institutions Domar writes:

let us assume that the economy has reached the position where the net average productivity of the free worker (Pf) is considerably larger than that of a slave (Ps). The abolition of slavery is clearly in the national interest . . . but not necessarily in the interest of an individual slave owner motivated by his profit and not by patriotic sentiment. He will calculate the difference between the wage of a free worker (Wf) and the cost of subsistence of a slave (Ws) and will refuse to free his slaves unless Pf – Ps > Wf, – Ws, all this on the assumption that either kind of labour can be used in a given field. As the economy continues to develop, the difference Pf – Ps can be expected to widen. Unfortunately, the same forces—technological nature of technological progress and capital accumulation—responsible for this effect are apt to increase Wf as well, while Ws need not change. We cannot tell on a priori grounds whether Pf – Ps will increase more or less than Wf – Ws.

(1970, p. 22)

Thus inefficient labor market regimes can persist even in the face of direct competition from relatively much more efficient organizational forms. This theme will be expended upon below in further discussing the importance of institutions in affecting the labor market implications of economic globalization and the potential impact of increasing wages upon competitiveness.

An extreme form of labor market intervention is illustrated, in Figure 8.1, by the change in supply curve slope from LSFR to LSUNFR. In this case, increases in the demand for labor would have no impact on the wage. In other words, in the face of tighter labor markets generated by more economic globalization, for example, a labor market intervention takes place which prevents workers from reaping the gains which would otherwise accrue to them through globalization. Allowing for the labor market to function yields some increase in the wage rate the extent to which depends upon the elasticity of the labor supply curve. But this elasticity critically depends upon the labor market institutions and labor related rights in place in a society. The more rights which labor has (inclusive of the right to strike) the more inelastic is the labor supply curve. Elasticity is also affected (in contemporary economies) by the labor market related institutions such as unemployment insurance, government assisted job training, and medical care programs.

Thus, in a country with more labor rights there might be a labor supply curve such as LSFR and in a country with fewer labor rights, we might have a labor supply curve such as LSFR*. The right to engage in collective bargaining and to unionize can be illustrated (as it is conventionally) by an inward shift in the labor supply curve such as LSFRUN. In countries with relatively few labor rights, however, one would still expect some benefits accruing to labor as the demand for labor increases since increasing labor demand, ceteris paribus, increases the bargaining power of labor. Labor benefits more when a wider set of labor rights are in place and enforced. In face of increasing labor demand, labor benefits can be diminished by imposing labor market related institutions which reduce the elasticity of labor supply. It is highly significant to appreciate that the elasticity and position of the labor supply curve are critically affected by institutional parameters—the extent to which economic globalization is not independent of labor market institutions (related to labor rights and freedoms). Where such rights and freedoms are minimized, so will the benefits accruing to labor from economic globalization. This suggests that economic globalization cannot be critiqued as an event that harms workers. Rather, on average, workers can be expected to benefit from globalization unless labor rights and positive labor market institutions (from the point of view of labor) are severely restricted. One means of improving labor’s level of material well-being is, therefore, to facilitate increases in labor demand. And, increasing the extent of economic globalization can be one such mechanism.3 The economic effects of globalization are therefore mediated by labor market institutions.

It is of interest to note that just as Smith recognizes the importance of relative bargaining power in determining the economic benefits workers derive from employment, the contemporary World Bank does the same and supports the entrenchment of “core” labor rights and freedoms as a means of workers and peasants securing more economic gains from engaging in the market economy and, related to this, securing gains made possible from economic globalization. In the World Development Report, 2006 (see also Sen, 2001), at a general level, it is argued:

Stronger civil and political rights and broader mechanisms for voice can reduce the likelihood that the government’s labor policy agenda will be hijacked by politically powerful groups. There is a strong association between democracy and the level of wages, both across countries and within societies that have experienced a political transition.

(World Bank 2006, p. 188)

Specifically, with regards to trade unions it is argued:

Formal trade unions are most effective at improving conditions for workers without huge efficiency costs when product markets are competitive, so that unions cannot raise wages for their members by capturing rents at the expense of other parts of society; when collective bargaining arrangements and institutions have enough flexibility to accommodate different demand and supply conditions for different types of workers; and when unions operate in a context that allows them to internalize and absorb the cost of their actions. On the other hand, when unions are co-opted by political elites or by the state, their actions can have significant costs for efficiency.

(p. 189)

Thus, not all types of unions or union activity need be beneficial to labor and society at large, but unions per se are viewed as a positive institutional attribute of market economies.

Apart from unions, the World Bank regards social policy as another important attribute of labor rights in well-functioning market economy:

Providing income security is another area in which the structural context and design specifics, which pay attention to incentives and reward desirable behaviors, are critical to policy outcomes. This is also true of minimum wage policies for which the key to avoiding large efficiency costs is to get the level right and to allow for enough flexibility across types of workers to accommodate different demand and supply elasticities for their labor. Design specifics and the broader structural context are equally critical to the success of legislation on other work standards (health and safety) or protection for specific vulnerable groups (such as child laborers, ethnic minorities, or the disabled). There is an international consensus that core labor standards—freedom from forced and child labor, freedom from discrimination at work, freedom of association, and the right to collective bargaining—have such intrinsic value that they should always be pursued. But even for these core standards there are questions about how to achieve them most effectively and with minimum cost.

(p. 190)

For the World Bank, interventions need to take place which enhance the labor market capabilities of workers and peasants. But the World Bank remains concerned that such capabilities will negatively impact upon economic efficiency and competitiveness, where such concerns are to a certain degree derived from assumptions underlying the conventional neoclassical model of the firm.

In terms of the conventional model, on the product market the increased demand for firm output yields an increase in equilibrium price such as D0 to D1 in Figure 8.2, increasing price from P0 to P1. If one increases the extent of labor rights and freedoms inclusive of the right to unionize, as suggested by the World Bank, this increases the slope of the product supply curve and shifts it inward such as from S0 to S1, as the product supply curve is affected by the cost of labor. At an extreme, the supply curve could shift to S*, increasing product price such that the quantity of output demanded will not increase. Further, inward shifts in the supply curve would reduce equilibrium product demand. One can expect a ripple effect in the product market wherein the product demand curve shifts outward in markets not directly affected by increased product demand. This representation of changes in product price as a consequence of increases in wages is considered to be a long-run phenomenon. So that even if the long-run supply curve was perfectly elastic as it would be in a constant cost industry, it is assumed that increasing the bargaining power of labor shifts this horizontal cost curve upwards yielding a higher long-run equilibrium product price.

Corporate leaders and representatives often express fear that increasing real wages, for any reason, will make them less competitive, given its expected positive effect on product price, yielding a fall in output, causing economic harm to all. Thus, state intervention is required to preclude labor from taking advantage of newfound labor market capabilities engendered by increasing product market demand. Of course, as per Figure 8.2, increasing wages, shifting the supply curve inward would only in extreme cases vitiate the positive effects on the equilibrium output supplied which an increase in demand would have. Nevertheless, concerns about higher wages relate to the expected results which are embedded in the conventional modeling of the firm, that increasing wages yield increasing prices, thereby making the firm less competitive. Such price increases it is argued are not sustainable in a competitive economy. High wage firms will face difficult times. Thus, although globalization is often welcomed by business, it is hoped that state will intervene to keep wages at bay as the demand for labor increases.

Globalization and a behavioral modeling of the firm

The conventional wisdom assumes that economic agents work as hard and as well as they can at all times, irrespective of wage rates, overall working conditions, and system of industrial relations. Thus, productivity per unit of effort input is at all

Figure 8.2 Globalization and product markets.

times being maximized. Leibenstein refers to such a scenario as x-efficiency in production. Conventional theory assumes that firms produce x-efficiently. It is moreover assumed that technological change is exogenously determined—it is determined independently from wage rates, overall working conditions, and system of industrial relations. But evidence suggests that these assumptions are largely incorrect empirically and that wages and related costs can positively affect effort inputs and thereby productivity and the quality of output (Altman 2001b, 2002; Buchele and Christainsen 1995; Gordon 1996; Ichniowski et al. 1996; Leibenstein 1966; Miller 1992; see also Chapters 2 and 3). In this case, unlike what is predicted in the conventional model, labor productivity can be expected to be below the maximum unless the incentive system facilitates higher levels (in both the quantity and quality dimensions) of effort input. Levels of effort input below the maximum yield x-inefficiency in production. Given the possible variations in the level of effort input, changes in labor costs need not have the effect upon unit cost predicted by the conventional model. The more realistic behavioral assumption that effort is a variable in the production function serves as the basis for a behavioral model of the firm, the details of which are presented elsewhere (Altman 1992b, 2001b; see also Chapters 2 and 3), wherein unit cost need not vary with changes in labor costs, unlike what is predicted in the conventional model.

Flowing from the basic production function (where output is a function of labor and capital), the essence of the conventional model as it pertains to this chapter, is given by equation (8.1), where one assumes for simplicity one factor input (labor):

where AC is averge costs, w is the wage rate, L is labor input, and Q is total output. If effort is fixed at some maximum level, any increase in the wage or related benefits to labor results in higher average cost. This speaks to the concern that increasing labor costs will negatively affect the firm’s competitiveness, especially in an increasingly competitive environment. On the other hand cutting labor benefits results in lower unit cost.

The extent to which unit cost is affected by changes in labor cost in the conventional model is not nearly as clear-cut as it might first appear since the extent to which unit cost increases for any given increase in wages depends upon the percentage share of labor cost to total cost. The percentage increase in unit cost which flows from a given percentage increase in labor cost diminishes with increases in the percentage share in total costs by nonlabor inputs. This point is expressed in Equation (8.2):

where AC is average costs, dAC is the change in average costs, w is the wage rate, dw is the change in the wage rate, L is labor input, and NLC is nonlabor costs.

Thus, if labor costs comprise only 50 percent of total costs and labor costs increase by 20 percent, unit production costs will increase by 10 percent. If labor costs comprise 100 percent of total costs the same 20 percent increase in labor costs yields a 20 percent increase in unit costs. Nevertheless, in the conventional model, labor cost increases yield increases in unit costs, albeit by how much depends on the share of labor costs in total costs. Therefore, if high wage firms are to remain competitve they must be protected by tariffs, subsidies, or nontariff barriers. The alternative is for high wage firms to become low wage firms.

In the behavioral model, increases in labor cost yield increases in effort input and vice versa. Thus, high wage firms can remain competitive even in a highly competitive environment if the relatively higher wages are compensated by higher levels of effort input—if high wage firms become relatively x-efficient. On the other hand, low wage firms cannot be expected to drive out of the market high wage firms when low wage rates are causally related to relatively low levels of effort input. Given the existence of effort variability and a causal relationship between effort input and labor cost, high and low wage firms can survive simultaneously in competitive equilibrium if differences in labor cost are offset by differences in effort input—if they operate at offsetting differential levels of x-efficiency. In terms of equation (8.1), as long as any change in w is offset by a corresponding change in Q/L, which is affected by variation in effort inputs, average costs do not change as production costs and levels of x-inefficiency vary. In terms of equation (8.2), as long as labor costs do not comprise the sum total of all costs, any given increase in wages or labor costs need not be matched by a proportionate increase in productivity for unit cost to remain unchanged. More generally, lower levels of x-efficiency need not result in higher unit production costs and higher levels of x-efficiency need not yield lower unit production costs. It would be possible for there to exist in competitive equilibrium an array of firms characterized by different wage rates, related production costs, and levels of working conditions, producing at an identical unit cost, if these differentials in costs are compensated for by differentials in the level of x-efficiency. 4 From a material welfare perspective, however, the higher wage firms and economies yield higher levels of material welfare, where labor reaps significant benefits. Lower wage firms and economies experience lower levels of material welfare, where labor bears the brunt of shortfalls in material welfare. Moreover, it is the differential levels of and increases in labor costs which induce the different levels of and changes in material welfare.5

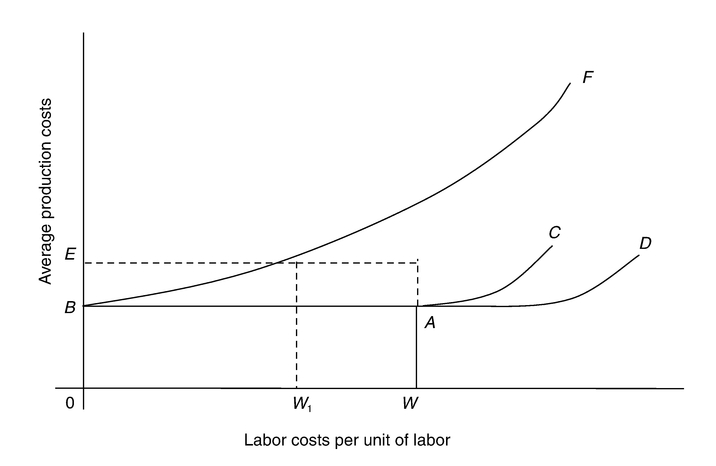

This argument is illustrated in Figure 8.3, where a unique average cost 0B is associated with a range of wage rates and related labor costs up to a point 0W where increasing effort can no longer fully compensate for increases in labor costs. Given technology, over a range of labor cost, high and low wage firms can remain competitive. In the conventional model, any increase in labor cost yields increasing unit cost as is illustrated in average cost curve BF. Higher wage firms can survive only if protected from competitive pressure.

Figure 8.3 Average costs and alternative costs of labor.

To the extent that technological change (for more details see Altman 1996; Chapters 6 and 3) is partially endogenous—affected by changes in labor costs—increasing labor costs shift outward the “average cost” curve from BAC to BAD. This increases the extent to which a firm can sustain increasing labor costs without experiencing an increase in average cost. Technological change is endogenously induced as firms develop and/or adopt technology which is new to the firm to keep average cost from rising. We have an inward shift of the production isoquant as opposed to a movement along it (for details, see Chapter 3). Low wage firms need not adopt the new technology or innovate if they can effectively compete on the basis of low wages and poor working conditions. Moreover, the latter may result in labor being too x-inefficient for the new technology to be cost effective. In other words, in a low wage regime, the low level of x-inefficiency is such that even when low wage firms use the more advanced technology they will not be producing at a lower unit cost than the high wage firms. Maintaining the old technology along with the low wage regime is cost competitive with high wage relatively x-efficient firms using the more advanced technology. To the extent that the new technologies yield lower average costs irrespective of the wage rate and level of x-efficiency, these technologies are of a “dominant” type. They would even have to be adopted by x-inefficient low wage firms so that these would remain competitive against their high wage competitors. In this case, technological change induced in the relatively higher wage economics (because of the impact of economic globalization) has a positive ripple effect on low wage economies.

In the x-efficiency type modeling of the firm, average costs need not be higher with higher wages. Moreover, lower wages need not result in lower unit production cost. Therefore, given the prevalence of relatively high wages and labor standards, there need not be any economic incentives for the firm to attempt to cut real wages. On the other hand, in this scenario there is no clear economic incentive for firms to facilitate increases in wages and labor standards unless the preferences of firm decision makers incorporate the preference of labor to improve their level of material well-being. Also, once relatively high wages are in place, as are a core set of labor rights which facilitate labor’s bargaining capabilities and from Adam Smith’s perspective level the bargaining playing field between labor and management/owners, there is some economic incentive for firm decision makers not to engage in efforts to cut real wages.

There is strong empirical evidence that cutting real wages over the course of the business cycle yields higher unit cost as effort input falls to such an extent that this offsets any gains accruing from wage cuts—labor retaliates against managers/owners for reducing their benefits. This is the essence of the efficiency wage argument for why nominal wages are sticky downwards over the business cycle (Akerlof 2002; Akerlof et al. 1996a, 1996b; Bewley 1999). To the extent that reducing wages serves to ratchet upwards average costs from B to E in Figure 8.3, at least in the short run, firms will reduce their competitiveness by reducing wages. Therefore, to the extent that economic globalization induces wage increases, these higher wages can be expected to be sticky downward given that adverse demand conditions are cyclical and that institutional parameters positively affecting labor’s bargaining power remain in place.

The introduction of x-efficiency and endogenous technological change into the modeling of the firm implies that fears which firm owners and managers have pertaining to increased labor costs are at best exaggerated. Improved working conditions need not increase unit cost if compensated by improvements in x-efficiency and induced technical change. With regards to Figures 8.1 and 8.2, respectively, inducing increased x-efficiency and technological change serve to shift outward the labor demand and product supply curves. In terms of Figure 8.2, expected increases in unit cost caused by the improved bargaining position of labor can be neutralized by induced improvements in x-efficiency and technical change. This offsets the negative effects which increasing labor costs might otherwise have on the economy. There would be no net shift in the product supply curve. On the other hand, lower wages, by reducing the level of x-efficiency, can result in an outward shift of the supply curve in Figure 8.2, offsetting the expected reduction of unit costs from deteriorating working conditions. Thus, the net effect on the supply curve would be for it to remain stable as wages change, as opposed to shifting, as is predicted by the conventional model.

The behavioral model of the firm, suggests that increased labor costs induce a more productive economy whilst lower labor costs have the opposite effect. Higher wages and improved working conditions are sustainable in a competitive economy. By strengthening the bargaining of labor, globalization can be expected to improve working conditions and material welfare if appropriate labor rights and freedoms are in place. Unlike the conventional modeling of the firm, the behavioral model suggests that changes in wages and overall working conditions affect the size of the economic pie. Moreover, the impact of improved material benefits to labor should not be assessed in terms of a zero-sum game since the pie increases with increases in labor compensation. Benefits accruing to labor in this dynamic scenario do not come at the expense of other economic agents (Altman 2004b; see also Chapter 2). On the other hand, viewing globalization as a necessary cause of increased absolute levels of poverty and overall socio-economic well-being (such as measured by the HDI) is highly misleading given the positive impact which increasing demand can be expected to have on labor. For such positive impact to be neutralized requires proactive state action against labor. Of course, if labor is to maximize the gains accruing from globalization induced increases in labor demand requires proactive state intervention providing and reinforcing labor rights and freedoms.

Conclusion

Economic globalization serves to enhance the labor market capabilities of workers, in terms of bargaining. Ceteris paribus, this should positively affect workers’ level of socio-economic well-being. To the extent that workers’ rights are in place and enforced by law (as are property rights), the positive impact of economic globalization on workers’ socio-economic well-being will be enhanced. If the state intervenes to neutralize the globalization related enhanced bargaining power of labor, labor need not benefit from increasing international trade. Extreme examples of such interventions are serfdom and slavery. A milder form of such intervention is exemplified by laws to ban or restrict workers’ rights to collective voice and collective bargaining.

To the extent that effort is a variable input and technological change is partially endogenous, corporate concerns about increasing wages are misplaced. Economic globalization serves to increase the socio-economic well-being of labor as well as inducing a more efficient and productive economy as increasing wages and improved working conditions provoke increasing efficiency and higher levels of technical change. To the extent that labor’s bargaining power is constrained, the productivity enhancing effects of globalization will be constrained and the economy will not evolve toward its productive potential. Although many will still gain from globalization, the majority will not garner the benefits that they would otherwise gain. These benefits which would not negatively impact on their economy’s competitiveness but would rather serve to increase their economy’s wealth.

If one’s objective is to improve the socio-economic well-being of workers, farmers, and peasants, economic globalization should be encouraged as should the establishment and enforcement of labor rights. Such improvements are Pareto Optimal from a material welfare perspective in the sense that the material well-being of labor can be improved without diminishing the material well-being of employers to the extent that increases in the level of labor’s well-being spurs compensating productivity increases (Altman 2002). In the tradition of Adam Smith, one can argue that economic globalization is not the root cause of economic deprivation—rather institutions which prevent the benefits of globalization from being realized by labor are the key culprits. Economic globalization is an engine of socio-economic improvements in terms of its potential positive impact on labor demand and the positive impact which the latter invariably has upon productivity and technological change. In itself, economic globalization contains the seeds that can and often do bear the fruit of significant socio-economic improvements for society at large, inclusive of the least and moderately well-off, when the appropriate fertile and nurturing institutional environment is in place.