Developments towards digital production

Publishing has been operating in a digital environment for decades. The production of content via digital processes developed alongside many of the key developments in computing for the general user. The digital environment has been the main way of processing information for some time and print products have for many years now involved digital production methods. Some sectors of publishing have advanced more quickly down this route than others and it was those sectors that developed genuinely digital products first, as we will see in Part II, particularly Chapters 6 and 7.

Developments towards digital publishing

What exists today has developed from various strands. These include:

- typesetting

- word processing

- desk top publishing (DTP)

- development of databases

Typesetting

Typesetting systems developed during the 1970s as publishers sought to streamline the time-consuming process of setting type. Manuscripts, previously marked up by hand and then typed into an electronic format, had code embedded in them at this stage to ease the creation of layout. These systems tended in the first place to be large commercial systems with special keyboards that allowed typesetters to label aspects of the layout such as headings, font styles and paragraphs. A variety of different codes developed (such as TeX and Troff) as different companies adopted different systems. Each had strengths and weaknesses for the user depending on the different operating systems and different levels of user-friendliness. The system was not electronic from end to end; to see what pages set this way would look like, typesetters had to output to paper.

Generic typesetting code began to be developed and screens were able to show what the text would look like once set, without the need for generating paper versions. This saw the development of ‘what you see is what you get’ (WYSIWYG). Large publishers developed their own systems (e.g. Oxford University Press and Wiley). Mathematical and scientific texts were especially critical in these early stages of development as it was this content that required complicated page layout; streamlining this complexity therefore would have clear benefits.

Word processing

In parallel to these developments advances in word processing were growing rapidly during the 1980s, and ways of creating or generating text within a digital environment therefore were growing alongside the manipulation of the text by the typesetting systems. Early word processors were being developed by a variety of companies, using different hardware and software, so offices often had dedicated word processing machines to replace their typewriters, possibly with linked printers (usually of poor quality). Typesetting from these was tricky as the variety of systems meant it was difficult for a typesetting program to cope with them, and printouts were low quality, so while work could be authored in a digital format, the text was still often rekeyed at the typesetters’ end.

Proprietary hardware for the consumer market broadly disappeared and the range of consumer computers reduced in number essentially to a choice between Mac and PC. Operating systems suited to personal computers began to settle around a few main companies too. As personal computing grew, so word processing packages were developed as part of a suite of software for PC and Mac hardware. Mac developed more advanced systems for showing a user what their work might look like on the screen (and today the Mac is the designer’s choice for its more sophisticated software in this area); as you could see what you were doing on screen, it was easier to make corrections on screen too. PC, however, gained popularity as a desktop option for business and individuals.

Desktop publishing systems

There followed developments in desktop publishing systems, which could manage a variety of layout issues and allowed for the creation of templates that made publishing easier to manage on screen. Publishing became easier to do in-house without using external contractors for the page make-up. This was helped by rapid improvements in the printers available at a consumer prices that could generate high resolution prints. As with the original word-processing packages, a wider range of new DTP systems developed, of which only a few survived, leading the market finally to coalesce broadly around QuarkXpress and InDesign. One other key development towards digitised production processes was the growth of postscript files – the system by which a file can speak to a printer. This allowed content to be output to postscript files ready for printing.

Database

Database developments formed a further strand in the growth of digital technologies for publishing. Databases had existed for a long time as a way of storing information. The issue was getting information out of a database in order to send it to production, and in doing so embedding the relevant typesetting codes in order to format it as necessary. The aim was to produce material that did not need rekeying from the database – as entries were always the same, content was more likely to retain its integrity if it did not have to be manipulated more than necessary; it only had to be input once and extracted as needed in whatever format was required. Lloyd’s List was an early example of the use of a database for publishing.

Technological developments towards digital printing

With technology enabling the faster and more efficient production of material various developments in the publishing process became possible. These developments also were able to change the business model around some aspects of printing. We will see later (p. 10) that the ability to hold information in one format but produce it in many formats was being developed, but even if the output was just to be print (rather than any sort of digital product) it was increasingly possible to print much more precisely in terms of both quantities and timing.

This coincided with the development of the digital printer. This has brought several benefits:

- cost

- small print runs

- timing – just in time and print on demand

- lower stock holding

- lower shipping costs

- local printing options

While the offset or letterpress printers are cheaper per unit cost for high print numbers, the time it takes to get them set up for small print runs is not commercially viable. The digital printer has developed so that, while it produces copies of lower quality (though this is improving all the time), it can be cheap where print runs are small. So as print book markets declined and print numbers reduced (for instance the academic monograph market), first ‘just in time’ printing and later ‘print on demand’ were opportunities available to publishers with the digitisation of the process.

Publishers can reduce the risk of holding large quantities of stock if they know that the material is in a digital format from which it is relatively easy and quick to print copies. Some companies have been set up predominantly for use by publishers (such as Lightning Source) but print on demand technology has helped fuel the self-publishing industry as well. Authors can now afford to pay for their own print runs, and there is no need for them to incur the cost of holding stock as they can reduce their risk by printing low numbers of books; entrepreneurial websites have developed to help those wanting to publish their own books themselves and these are using digital printing options.

An additional attraction of digital printing is that the set-up time for digital presses is extremely quick; where publication of a book needs to be timely there is the opportunity to manage the print stage quickly, for example for reprints. Offset printing for colour work can be expensive and so is often carried out in print works in the Middle East or Asia, but shipping times mean long lead times need to be built in. With the development of digital presses some of the printing that previously was taken over to China and Hong Kong is coming back into Europe. Being able to print shorter runs also makes it more possible to print locally for local markets and some companies are avoiding bulk shipping costs in this way.

Changing production processes and workflow

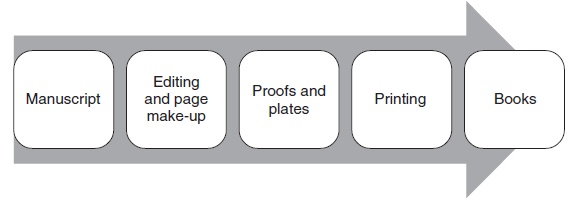

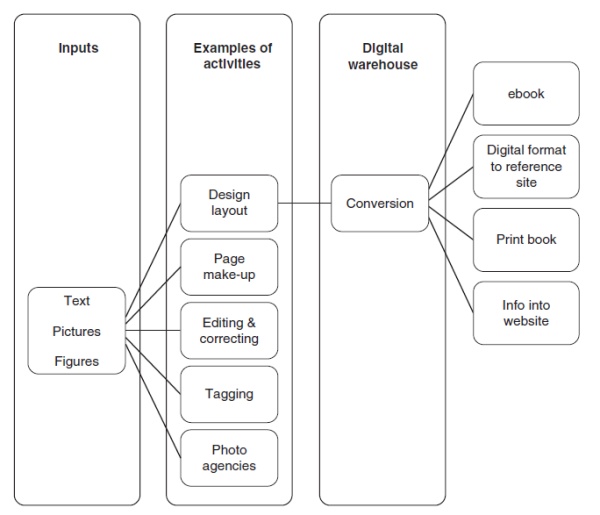

Many companies have been reviewing their workflow in light of the changes in production methods with the growing levels of digitisation within the process. Companies will design their production systems in terms of workflow, analysing different processes a product goes through from raw manuscript to final product. In pre-digital terms this was reasonably straightforward as a manuscript passed through various stages of copyediting and proofreading, through typesetting and to printing. It was broadly a linear, single-layered workflow which led to a final product, delivered in one format. Figure 1.1 illustrates a very simple workflow. Each stage would involve various checks, responsibilities and supplier relationships. As the digital environment has developed, various stages have become more complex. Figure 1.2 outlines the way various activities take place concurrently and are collected ready to output in various formats.

Workflow has expanded to accommodate two main issues:

- the ability to adapt the output from just one input – so that from one ‘manuscript’ many formats can be produced

- the need to streamline effectively various parts of the process, which can lead to cost savings, where certain activities are less necessary, or time saving, where content can be managed quickly through the workflow with as little intervention as necessary

One input many outputs

In the first instance, the aim is to prepare the content in such a way that the format is neutral in order for it to be readily used for a number of purposes. There are many format options, the common ones being:

- a print paperback (these can vary in size and binding)

- a print hardback (these too can be in different formats)

- ebook files of various sorts for different devices

- a PDF, which is often necessary for search inside mechanisms such as Amazon and Google

- ebook files that can then be manipulated further to form an enhanced ebook or app

- a file format that can be taken by aggregators to fit into their complex proprietary library databases

It also needs to be in a format which can be repurposed in the future in different ways (for instance in an anthology or in email bulletins or summaries of abstracts etc.). So the content is managed through the editorial and production processes to have structure added that allows different programmes to understand and output it in different ways. We will look more closely at structure later. The workflow is designed to ensure all the stages necessary to get the material into the right structure, whether text or artwork, happen, and do so, where they can, concurrently.

Where savings in cost and time are benefits, this has led to a variety of changes. The developments in digital typesetting and digital printing continue to progress at a fast pace. In the arena of typesetting there has been a large amount of automation, allowing publishers to make less use of external suppliers. Typesetters, therefore, have to work hard to reinvent themselves in a new highly technological environment. More and more of the typesetting processes are becoming automated, using coding on documents, taxonomies for types of content and materials, and standardised style sheets so that very early on in the process the product can be edited to a high quality and then later laid out automatically into templates, with much of the hands-on typesetting role reduced. Typesetters have had to adapt to bespoke systems designed by their publishers and become more specialised where the straightforward work has been taken in house. There is still a need for specialist companies to output from the digital format, to ensure high quality and overcome technical challenges; these companies need to work very closely with their clients to become embedded in the workflow. In addition, while typesetters in the past traditionally stored the film used for the printed books (charging for storage), these costs can be cut out altogether with the digital formats as content can be held by publishers in their own systems.

With printing similar changes in workflow are happening. There will be a demand for print for some time to come and printing is therefore a key part of the workflow, but as digital presses increase in quality, the ability to print smaller quantities as some readers migrate to digital environments is very attractive. While offset litho, as mentioned above, remains the cheapest option for high-quality, high-quantity runs, digital has the advantage of being able to manage small numbers quickly. The quality up to now has let it down somewhat, so print on demand products have tended to be for academic titles that can be run off cheaply as and when needed and in small quantities (even as small as one copy).

However, as the quality changes and as print runs come down (due to ebook purchase and other market influences such as cuts in schools budgets) digital printing is becoming more attractive for short-run printing, maybe as low as 500. Stock holding can be kept to a minimum, saving money, and reprints can be quickly organised. It is possible that the warehouses of the future, as they hold less stock, will build in the ability to print on demand or print short runs digitally.

Data warehouses and data asset management systems

Once information can be created in a digital format the digital environment where the content is stored and retrieved becomes critical. We will revisit this in Chapter 4, and again in the education chapter (Chapter 8), but essentially a data warehouse is the storage space or archive for digital content. From here titles can be easily retrieved for reprinting or sections can be extracted and repurposed. One of the debates for some publishers is what should go into the warehouse; when some of the older titles that do not exist in digital format (or indeed any format other than the book itself) need to be digitised it can be a costly business, even if it is just a one-off activity. Yet extensive digitising of the print archive may be important for some publishers to ensure the completeness of the data warehouse.

The digital warehouse can simply store the book in the structure necessary to reproduce it in any format and/or style required. But this can go further where a digital asset management system enables the elements of the content assets to be used more effectively and continuously. So, for instance, artwork of all sorts, from illustrations and cartoons to maps and charts, as well as photos and diagrams, can be stored and easily accessed to be used again. This, of course, saves money and maximises the use of materials already paid for and owned by the publisher. Additionally, textual materials, specific collections of copyright-free photos that have been bought in and commissioned video footage, for instance, can be stored to be accessed again for enhanced ebooks or resource-rich websites. This can be an important resource for producers of heavily illustrated books that may also involve a large amount of commissioned artwork or photos that the company owns. These can be used again or even become an income stream with the development of a commercial picture library (such as the one by DK, for example).

A considerable amount of investment is required that only the larger publishing houses can afford. But with these data warehouses in place it is hoped that the benefits strengthen their position as publishers as they are able to manage the material/content they commission and own as effectively as possible; they can develop an important resource from their archive, building up their content assets in order to compete effectively with global internet companies and ‘publishers’ such as Google and Amazon. Cost savings and efficiencies, as well as content, are therefore stored for the future.

Conclusion: changing publishing structures

Workflows are being redesigned to encompass these changing activities. More work can be managed concurrently and stored appropriately in sections, ready to be consolidated at the final stage and output as required. As this is done the roles of suppliers and activities in house change and are re-evaluated. The skills and roles for managing the different aspects of the process are evolving and different companies are adopting a variety of structures to accommodate the growing digital parts of the production work.

One area of development is the increase in outsourcing for particular activities within the workflow. Typesetting and printing have traditionally been outsourced, but as more specific roles are developed along the workflow, so more activities have been outsourced, from coding material to data warehousing. A large specialist publisher will typically have offices in countries like India and China, not just for carrying out sales and product development work for their local region, but also for work like programming and tagging for the company as a whole. Publishers are re-evaluating working methods and publishing structures around these new workflows and we will look more closely at these in later chapters.