Developments in digital publishing for the academic market

In this chapter we will cover:

- The academic publishing context, focusing on the way publications play a part in the research process

- Development of digital products and why these first evolved around journals

- What current digital products look like and the challenges they face, first looking at journal services and then at monographs; this section will look in particular at the issues of open access

- Future developments of digital products, exploring the themes that will influence the academic publishing market going forward.

The area of academic or scholarly publishing is another sector where the digital product is well established and has, in some areas, entirely supplanted the print product. Indeed, the area of academic and scientific research was the arena in which the internet and, subsequently, the World Wide Web first developed. The application of digital technologies to research was therefore an obvious step to take to improve and add value to content that was previously only available in print.

Research needs to reach across boundaries in order to be useful; dissemination is critical to the purpose and continued dynamic of research, and the World Wide Web in particular enabled that to happen much more quickly and effectively than ever before. Easy access to material for researchers, whether raw data or fully validated research papers, is critical, and print had obvious restrictions to the efficiency of access, limited as it was by shelf space and physical access to a library. So the digital environment was an obvious way to ensure these key precepts of research such as access and dissemination could be realised and research taken into new realms.

Context: the research environment

In this section we will explore the characteristics of research publishing, including:

- what research publishing is in both STM and HSS contexts

- who the customers are

- peer review and the role of publishers

- who owns the content

- the publishing dilemma for research

What is research publishing?

There are a few distinctions that need to be made around the area of scholarly publishing and the publication of research. These definitions are not strictly applied, and may be subject to debate, but it is important to be aware of areas where terms overlap, albeit loosely, as there are some differences in publishing strategies depending on the area of focus. Scholarly, or academic, publishing will generally refer to publishing based on research from academic institutions; research takes the form of academic papers published in journals as well as in book form. Scholarly or academic publishers will also produce textbooks suited to the higher education market as well as supplementary works that are more specialised than core textbooks, crossing over between the curriculum and the research of an academic institution. For the focus of this chapter, it is the research aspect of these publishers and their output that is key (we will touch on higher education textbooks in Chapter 8). However, research is not undertaken only within academic institutions, so publishing of this sort also encompasses material produced by research institutes, maybe governmental or private sector research organisations, as well as companies such as those operating in the pharmaceutical sector.

Drivers of the market

There are three main issues around research that influence the publishing environment:

- Dissemination: research needs to be spread widely in order for more research to build on it

- Distribution: scholarly publishing is global and the distribution needs to be too

- Storage: research needs to be collected and stored in an accessible way for easy access later on down the line

Publishers were able to do this effectively in print formats: as global businesses they developed the relationships necessary to spread information widely and in a targeted way to ensure appropriate dissemination; they could also help libraries archive it as far as possible. Digital publishing clearly provides ways to solve these problems even more effectively.

Journals and monographs

In many cases the primary source of published research material is a journal and that has been the focus of many of the digital developments in recent decades. However, there are also monographs, extended pieces of writing exploring and presenting a thesis in more depth, as well as collections of articles written specifically for a research book that are by a range of different authors, perhaps following a conference. These all form part of a scholarly publisher’s range of publishing.

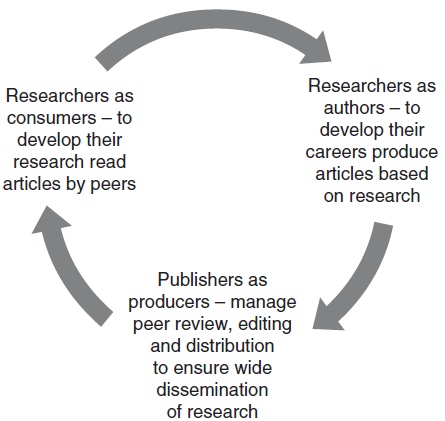

Thompson, in Books in the Digital Age (2005), explores the nature of the academic publishing field and the field of academia itself. These fields exist together, both needing the other, but with a different emphasis at the heart of their activity. Figure 7.1 illustrates the symbiotic relationship between research and publishing.

Academics want to disseminate their research and spread new knowledge effectively. Publishers have, until recently, provided the most effective way for academics to do this, so academics depend on scholarly publishing organisations to validate their work and ensure it is spread widely. Academics depend on them too for the materials they use for their research; they want to read what others have published in order to advance their own thinking. In addition they gain more credibility and authority the more their own work is cited in new research, so the mechanisms publishers have in place to monitor citations are also important for their career development. Publishers meanwhile need a constant supply of research material to publish, need to ensure it is of high quality and need academics to encourage their libraries to buy this material. For both sides of the bargain quality and validity are important, for the prestige of the publisher and for the authority of the research for the academic. So the relationship is interdependent: an academic will choose a publisher or journal based on the authority of that journal; the publisher wants high-level academics to contribute to ensure the prestige of the journal.

There is also an additional angle to the journal publishing field as there are many institutes and learned societies that own journals that are published by scholarly publishers. Publishers tender for the rights to produce the journal for the society and need to ensure that the particular ethos and mission of the organisation in question are supported in their publishing practice. These organisations have needed publishers as producing journals is an expensive business, and publishers can also maximise the commercial opportunities: journal publication is often a significant source of revenue for these societies.

It is important at this point to draw a distinction between STM (science technical medical publishing) and humanities and social science publishing (HSS – this acronym is not always used extensively but I will use it here). These are both fundamentally scholarly publishing arenas but aligned around different sectors of the academic market. Definitions of these markets vary but it is important to recognise that there is an element of STM publishing that has a strong overlap with the professional arena of science publishing (i.e. as undertaken by medical research companies, for instance). Some scientific journals have an extremely wide reach beyond academic institutions; an example would be Nature, which is a large publishing operation in its own right. Of course there are practical applications of areas of social science, law, education, finance, etc., and journals will feed into the more professional markets of these areas, but the main fields of humanities publishing tend to be centred in the academic environment (one exception being humanities titles that might cross over into general interest).

It is useful to make a distinction between STM and HSS areas within the arena of scholarly publishing as they have developed a little differently within the digital environment. Both sectors publish journals and monographs but the nature of research in each bears a slightly different emphasis. Historically the HSS markets have lagged behind the STM markets in moving into digital environments, particularly where, in the STM sectors, some journal publishers have moved away from print almost entirely. STM markets, for instance, are more significantly driven by:

- a more immediate need to spread scientific research in real time

- the ability to access scientific research quickly and easily in order to build upon it in a timely way

- the fact that the older the research is, the less useful it can be within the STM disciplines

For these the reliance on journals as a primary way to disseminate findings was already well established.

These are not insignificant issues for the HSS arena but there are some other nuances in the publishing business here:

- there is a strong tradition of the research monograph where academics can extend argument and develop understanding within a longer narrative form

- older journal articles or monographs can still be current within the context of a debate

- historical reference to earlier research sources will very often still be critical to the development of current thinking

- HSS academics are likely to be returning to older sources and research more often than their STM counterparts as this is critical to building a rounded picture for debate

For these reasons monographs are an important aspect of HSS publishing and that leads to more potential for a live backlist. This can be important for many publishers as a long-term revenue source; the writings of particular people such as famous economists or psychologists, for instance, may later become paperbacks as key texts move into the teaching curriculum.

So there is a difference between HSS and STM publishing which has meant that scientific journal publishing has, up to now, been ahead of the humanities research monograph in terms of migration to the digital platform. HSS has been catching up but it is still worth noting a slightly different approach as we look at monographs later. It is also important to note that there has been a faster drive towards English as the main language for all published material in the STM sector than in the HSS arena.

In the market for scholarly and academic publishing there is a distinction between the user and the buyer of the material. The libraries buy the journals and research works, following recommendations from the academics using the library, and these libraries are large institutional purchasers responsible for considerable budgets but, of course, under pressure to get value for money as a public institution. They may well form consortia to increase their purchasing power and they will be regarded by publishers as key accounts, with highly tailored sales packages planned according to their needs.

The libraries will have various concerns as they manage their books. They will be wanting to ensure they get access to the works right so that titles or journals are easily available to students and researchers; this needs to be managed with the popularity/importance of the journal in mind, yet they do not want to restrict the lesser used journals too much, thereby limiting the possibility for their researchers to access everything they might need. But their budgets are not unlimited so they need to balance the titles they take between popular, ‘have to have’ journals and ‘nice to have’ journals. They will, in most cases, spend the full value of their budget, so if a new title comes along, they may well need to reduce their stock somewhere else in order to afford it.

The publishers need to bear various issues in mind for their library customers, such as effective customer service, fast distribution and, of course, pricing, as well as recognising the competing draw on library budgets (for instance to supply technology for use in the library or buy other resources such as DVDs). Shelf space is also a growing issue for some libraries as well as the ability to manage ever-increasing archives. But publishers also need to be satisfying the users – ensuring the titles are easy to use, well designed, high quality in terms of the content, and properly referenced and indexed to ensure the information is as easy to get at as possible. These issues have always been important and are critical in the move to a digital environment.

Peer review and the role of publishers

The importance of validity has already been mentioned and the main way this is achieved is through peer review, whether as a journal article, through a peer review process, or as a monograph or thesis where influential readers will have considered the work for publication. In the journal arena, of course, this is an ongoing process that forms the backbone of journal publishing. As new articles come in for consideration the peer review process is continuous and thorough. If peers accept the research it is regarded as validated and sound. This also reinforces the nature of authorship as researchers can lay claim to an area of research; copyright in the material once published further protects their material from misuse such as plagiarism. One of the central tenets of copyright is the protection of authors so that they can expect to be recognised as authors of their material while allowing it to be applied where relevant to further research initiatives; with recognition for their work, authors are inspired to continue research and so creativity and innovation continue to be nurtured. With copyright comes citation and this forms part of the area in which publishers can add value, by providing citation indexes, for instance, or ensuring work is properly referenced throughout their published output.

The key issues with peer review are:

- it is time consuming

- it requires effective organisation

- it needs to meet high standards

- it comes at some sort of price

The cost of peer review has been effectively borne by the publishers, who, if they manage the publication effectively, hope to recoup the cost through their own sales, and thus support the activity.

Research, in many cases, is carried out by people funded in their various countries by the state: universities and research institutes are very often supported by the public sector and research grants will frequently come out of the money paid to the state by taxpayers. So if the research outcomes have been paid for once already should the research not therefore be free to access? In addition to the issue of the number of times the content is paid for, there is the moral consideration which raises the issue that the commercial appropriation of research content goes against the grain of research as open and free for all to use and benefit from. The ethics of disseminating research have come to the fore now that methods of dissemination are much easier and cheaper with the use of digital technology.

This has also enlivened the debate about open access. We should consider briefly the terminology used in relation to open access. Open access essentially means that material is available online and with unrestricted access; research material can be lodged in various places such as a public subject-specific archive or an institution-specific archive. The terms open source and open content licensing are both used in the context of open access. Open source can be used interchangeably with the term open access but in general is used in relation to the release and exchange of software, while content in other forms of media (e.g. published in journals) is covered by the term open access. Open content, while also somewhat non-specific, can be used when referring to content that can be modified in some way, something we will look at along with usage rights when we consider Creative Commons in Chapter 10. These principles have been around for some time now: self-archiving/sharing was originally carried out by computer scientists in the 1980s, with a considerable body of articles available as open access by 2000. Scientific journal articles have led the way. This is especially true of the newer subject areas which have been developing in more recent decades; with less heritage of print journals behind them it has been easier for those titles to step directly into the online world.

We will explore the challenges in more depth on p. 73, but the issue centres on the accessibility of research and the value it provides. The argument goes that if research helps mankind in some way, then if it is limited only to those who can afford to pay what may well be high subscription rates to journals surely that is preventing research from moving as fast as it could in order to continue helping mankind; and does it not also prevent those in poorer countries from accessing it at all?

Ownership of content is being reconsidered more acutely as universities lay claim to the work carried out within their departments; while not denying moral rights of authorship over content (so not affecting the ability of an individual to gain recognition and accolades for their work), universities and institutions where researchers carry out their work may claim copyright over material which could allow them to exploit the material more effectively for themselves as an institution.

These are not new concepts but the freedom and democracy of the digital environment have allowed the relationship between the commercial product and the need to sustain and disseminate well-tested research to be reconsidered. The peer review process is central to the continuing model of research and yet this part of the research equation has not been entirely covered by the academic sector in the past, but supported by the commercial journals market. So if the process of dissemination moves away from publishers as universities and researchers experiment with different forms of access with different models, there is still an issue of the cost of managing a peer review process, which is not negligible and needs to be considered in some way.

From these debates, it could be said that publishers are beginning to seem less important in the process of research publishing. The cost of peer review aside, other costs that had made publishers essential to the research dissemination process are changing. While journals were only available in print, the additional production and distribution costs also needed to be covered by publishers; they could invest in this and build the value chain necessary to do this, so were the only real option for disseminating research information effectively. Digital publishing has led to a re-evaluation of journal publishing as it becomes easier to disseminate information in other ways that do not necessarily need to involve a publisher.

Changes in the publishing value chain are leading to changes in the cost base for books. The costs of printing and global physical distribution are immediate savings that can be made. Given the critical importance of timeliness in spreading information and competing effectively in a research market, which, of course, the internet enables so well, the benefits are clear. While academics and their institutions were not really able to set up a global distribution network for print output, the dissemination of their research on the internet is something that it is possible for them to undertake, thus threatening the position of scholarly publishers. This will continue to be a theme through the chapter.

The development of digital products

In this section we will look at:

- why digital products work for this market

- the early development of products and why journals articles were first

The benefits of digital over print

The digital environment could immediately bring obvious benefits to the scholarly and academic markets. Many of the critical issues that are part of the research environment could be immediately solved. There were many limitations of print:

- timeliness of accessing the research could well be limited if the journals came out bi-monthly or quarterly in print form

- the ease of access for large numbers of people was difficult to manage if only one print copy was available

- users had to be in the library physically to use the products

- shelf space could well be limited

- searching library catalogues could be time consuming and was not always revealing

- dissemination was still limited, particularly in developing countries

These issues could be quickly solved by digital products.

The value of content to the library

Libraries need information in order to manage their collection effectively. Libraries wanting to ensure value for money need to understand how popular and useful a title or article is. A book physically booked out of the library will leave a record but titles referred to within the library are more difficult to trace; while a well-thumbed section of a journal can indicate a popular article, it is difficult to monitor in a systematic way. Yet this sort of information allows a library to establish much more precisely the value of a particular title to them. There could be journals that they do not want to stock in entirety but which have a few articles every year that could be of interest to users; in print formats this is almost impossible to manage. There could well be additional costs in purchasing bound volumes of journals, an important way to ensure durability for well-used titles.

The early development of new digital products

It was clear, therefore, early on in the development of the sector that a digital product could resolve many of these issues. There had been early efforts to move scholarly content into digital environments but the main expansion followed the development of the World Wide Web, and the move to digital platforms for this market started in earnest in the mid-1990s. Publishers began to focus on developing more commercial products and finding ways to migrate their content into digital environments.

As Table 7.1 summarises, adopting technologies for journals was easier to manage than the transfer of books, as the rolling programme of delivering and typesetting articles that already existed allowed for the introduction of digital platforms in a more controlled way; smaller chunks of information such as articles are easier to code and manipulate on a rolling programme, and workflow could be adapted to phase in digital platforms.

Journals |

Books |

Rolling programme of articles being delivered Short articles easy to code |

Manuscripts delivered at irregular intervals Large manuscripts |

Structure of articles often written to defined style (e.g. with abstracts, keywords, references) |

Different author styles and possible varying series/house styles |

Archive easy to build up on a continuing basis |

One-off titles that stand alone |

Articles easier for customers to read online and customers are more used to an online environment for this style of publishing |

Long narratives not always so easy to read online |

Shorter turnaround for preparing articles |

Longer time needed to get the work ready for digital service |

Archives easier and quicker to digitise |

Books more costly to digitise and more inconsistent in style |

Journal publishing more profitable and so investment more readily available |

Books less profitable, and more difficult to find a framework in which to sell digital content |

Pricing easier to manage – libraries used to subscriptions |

Different sales model required for libraries, while ebook models for individual purchase were less developed |

DOIs and other structured systems make it very easy to handle articles |

This has proved more of a challenge for books |

The journals market in particular was highly concentrated around a few key players with global scope and financial strength. As they developed more online systems a critical mass quickly developed, which in turn encouraged the market to move relatively quickly into online usage. Online journal models developed reasonably quickly and libraries were quick to see the opportunities in buying new services, so providing good models for the smaller players to adopt.

The production of specific journal issues still currently remains the dominant pattern for journal titles (as opposed to continuous publishing making articles available as and when they are ready), but the digitisation of content was more manageable and digital archive started to grow early on, so that now good digital archives exist; for key titles, previous print issues will also have been put into a digital archive. Even the peer review process could be integrated into the digital workflow, with authors delivering into a platform where readers could access review and carry out debates about the material (as mentioned above); manuscripts can be submitted directly to the journal front page within a publisher’s catalogue too in some cases.

What current digital products look like and the challenges they face

In this section we will consider journals services first and then explore the different challenges facing monograph publishing.

Digital journal services

The digital products that have been developed therefore broadly take a similar structure: the articles are available in a digital format and users access them through a front end or portal, usually integrated into the library’s own system, that allows them to search in various ways (from title and author to keywords) across the digital database to access either an issue as a whole or a specific article. Users therefore can search across a wide range of titles at once and hop between articles easily where links have been created. Additional benefits may include places to save past searches or build a reading list of titles, as well as the ability to explore other archives that may not be part of the full subscription package to see how relevant they may be. Individuals can also access these via portals on the web, and pay, according to their needs, a subscription or a pay per view/use/download price.

Benefits for users

Digital products such as these could clearly offer from the outset five unique features that overcame particular limitations of print:

- timely dissemination

- global access

- searchability

- discoverability

- more flexible use of content

Journal articles can be posted up as soon as they are available (suitably reviewed) online, even if they still have some link to a particular issue that might come out in print later down the line. In addition users can access these articles much more immediately: they do not necessarily have to wait until they get hold of a physical copy in the actual library; they can access the information from their desktop wherever they are. Products are searchable now in an easy to use web browser so reaching specific content or tracking down particular information is quick. Not only that, but discovering content one did not know about is quick too as the search allows for fortuitous discovery of other articles and information that might, for instance, appear in a journal from another discipline that might not normally be stocked. That also means that direct hypertext links can be made between titles, and not only titles owned by one publisher but across a series of titles. Titles can be grouped in different ways according to their users. Furthermore, with the texts accurately marked up and resting in a digital warehouse, they can be used in a variety of ways in the future as they can be accessed and formatted differently according to market needs; customised lists of readings, for instance, can be collected together and this may be valuable for some users.

Benefits for libraries

For the libraries too there are many benefits:

- measuring use

- flexible payment according to use

- fulfilling the demands of their customers

- value for money in purchasing

They can measure very effectively how the products are used. This can lead to different scenarios: they know how well used a journal is so they can justify keeping it on their list; but they can also see quickly what is not used enough and take it off their list. For more obscure journals they do not want to stock, they may be able to pay for access as and when necessary, by pay per view options, saving them money from stocking something in its entirety. They can also fulfil demand much more effectively as users do not have to wait to access the limited number of copies; users can access articles from wherever they are and a library can pay for a number of licences that allow several people to access the article at once. The management and access controls that many of these platforms have can also help the libraries understand their use and their users. Overall the libraries should be able to get better value for their money by buying more accurately according to the needs of their market.

The importance of usage

The production of digital information and in particular the considerable change in infrastructure that it required is costly, however, and libraries are not necessarily saving money as they have to accept that there are charges for obtaining the material in a more flexible format. The publishers also can see quite how critical a title is for a library with usage figures, and so both parties need to negotiate carefully to ensure fair pricing. This has meant deals have become more complex and customised.

The monitoring of use is important for publishers not just for their negotiation with libraries. In a competitive marketplace they need to show that their journals remain leaders in their fields. They will monitor citations, which they can track digitally in order to show which journals are most frequently cited. This is particularly important in the arena of society journals, where journals are put up for tender by their owners (the learned society) and publishers need to show how far they are able to promote the academic authority of the journal both in terms of wide and effective distribution (so that the material is picked up on quickly) and in terms of the quality of the content itself. It is this aspect of journal publishing that is important for academics too, as we have seen, and so the digital environment has made it easier for academics also to measure the success of their published output.

Product sales and deals

Users can buy digital products in various ways. Publishers will produce each individual title with a subscription price, which is often tiered with a print and electronic bundle, or an e-only or print-only option. This is just the start of what can be a quite an extensive menu of prices. There may be prices for institutions (which may indicate access for a number of people), as well as prices for individual subscribers wanting their own copies/access, and there may be prices for individual issues and archived issues; the relationships between these prices have been an active area of experimentation for many years.

However, the price for an institutional purchase is determined by the arrangements and negotiations between the libraries and the publishers. The size of an organisation as well as the type of people using the databases will also be taken into account. Publishers may put together collections of titles in different packages for libraries to choose from (e.g. Elsevier Science Direct). They will provide front end access to their journals so that users can search across them all and they may have premium levels that can, for instance, allow access to other journals on a need basis – so that organisations only pay where the user downloads a particular article. While the prices will be, to some extent, negotiated based on pricing menus, libraries may well end up with titles they do not want in their packages, but it can be difficult and expensive to tailor entirely a package to an individual institution’s actual use; buying a package is usually the cheaper option. There will be bespoke options where customers can select from a range of titles within a package, though a minimum order will usually be required. There will be other levels of control around the ability to download entirely or print. Further aspects of added value (these are not necessarily always charged for, but form part of a title’s competitive edge) can include:

- email updates about forthcoming issues

- online-first options

- citation alerts

- viewing samples or abstracts for marketing purposes

Some libraries may have their own front ends, to which they connect their different publisher materials, and there are arrangements (e.g. Shibboleth) that enable one main password to be assigned and used by an institution across a variety of products. In addition there is a drive towards multiple-year purchases – three- to five-year deals – and the importance of having access to non-subscribed journal content is growing.

Advances in usage analysis, as mentioned above, can help libraries get a very accurate picture of what is used and not used to enhance their negotiation power. Publishers can use this to their advantage too in sales pitches as they can clearly demonstrate how far journals are used and so prove they remain essential to the package. However, the changes do bring problems. The print subscription price and any special discounts applied to the whole deal were transparent. Prices now may be set with more knowledge of precise use but libraries have to be able to understand a whole range of different pricing mechanisms, and publishers have to ensure their customers are happy with the price and value of the product. But if librarians start to be more selective about their package it can act against publishers, who may be supporting smaller journals, still essential to research, on the basis that they are part of the package with journals that are used more extensively.

Aggregators

The other major way to access journals in digital environments is via an aggregator. They will collect journals together in packages from various publishers and present them via their own platform and front page. Their selling points will be based on their ability to allow searches across different publishers’ products, select and package groups of materials appropriate to their customers, provide price benefits where their negotiations with publishers have allowed them to benefit from economies of scale due to their wide customer base, as well as effective management and control tools for librarians. These aggregators include people like MD Consult, ingentaconnect, EBESCO, Pro Quest, Gale – but there are also specific ones serving corporate markets like infotrieve, reprints desk. The benefit of getting the full range of subject relevant titles is clear but there can be problems with these where deals go wrong, and publishers can suspend or withdraw titles from these arrangements, leaving a library exposed. While aggregators are a key part of the market, the larger journal publishers see that by dominating an area they can sell their packages direct to their key market and will be strategically trying to advance their position in the market.

Nevertheless licensing to aggregators and other third parties remains a key part of a publishers’ strategy. It is an additional sales channel with the following benefits:

- maximising reach and readership – which is critical also to authors/editors/societies

- allowing publishers to become involved in sales and distribution mechanisms they may not be able to access easily themselves – e.g. into different territories, within new formats, utilising new technologies

- ensuring wide access, one strategy in preventing piracy

- allowing content to be managed in different ways, but always ensuring copyright is protected

- enhancing sales revenue from the main market as some libraries will prefer to use third parties rather than go direct or work with consortia

- accessing new markets – e.g. institutions that may not focus on research but where students may find access valuable; individual consumers; pay per view access for the corporate market

- aggregators are extremely well integrated into libraries and spend a lot of money focusing on the technology which is their USP, so they are a critical market

The challenges for digital journals

Changes from the print business models

So for publishers the business models revolves around the following:

- subscriptions on a title by title or package by package basis

- library and library consortia purchase of titles and/or articles

- bespoke licensing to customers

- licensing to aggregators

This has not changed markedly from the print model, in that subscriptions still form the foundation for the product sales, but there are challenges in these business models specific to the digital context, which include:

- investment in product development

- authoring

- financial strength of smaller journals

- the challenge of open access

The ability to customise, pick and mix and supply to aggregators has required considerable investment in digital platforms and workflow in order to manage content in a way that can be used in these many different outputs. The importance of being able to connect to third parties such as aggregators means the development of protocols has been critical to publishers’ successful development of their content, ensuring their content is in a format standardised enough to be used by different people within different platforms. This comes at a cost and requires a lot of development work up front.

For authors (or journal owner such as the learned society) this means a change in various aspects of the process. The way they deliver work is now much more controlled by the workflow system of the publisher, and authors may have to work within new digital environments when they deliver and edit their work. Their material is being accessed in a variety of ways. This can lead to increased royalties as there are wider opportunities for access, and contracts need to cover different types of payments for different types of access (e.g. pay per view, usage rates or volume sales rates). It is worth noting that the contracts for journal articles and monographs in this arena have covered digital rights very clearly for some time, and while early backlist titles do need to be re-evaluated in terms of digital rights, the problems around author rights and contracts have been less than for the trade market.

Assessing success in terms of the financial strength of a journal can be more involved. In print it was transparent, as one could assess success title by title. Now content may be much more embedded in the package deal and assessing the success of an individual title can be more tricky. The profit and loss of a title is more complex and this may change the premise on which some journals survive; this does not necessarily mean the end of small journals: some journals may find that life as a pay per view title on the outskirts of a package rejuvenates them with new revenues; with lower costs for production and distribution they can survive on lower revenue. But equally, as mentioned above, journals may find themselves under pressure if good levels of active usage are not proven: important titles that have niche markets may suffer as their purchase cannot be justified by librarians, and as margins with publishers remain under pressure there is less profit on the larger titles to support the specialist ones. The support a learned society provides for certain specialist journals is critical. This once again opens the debate over whether if the journal is already subsidised it should then be commercially exploited by a publishing company.

The move to the digital environment has been swift in this area, so fast that the print products are declining rapidly and in some cases are no longer produced except on demand. The STM arena in particular has been quick to move. To some extent this reflects the range of product needs outlined above: digital products have so many advantages over print ones. But it also is because the internet was already being used in this way by researchers – unlike some professional markets, where users might still very often show a preference for using print, the scientific community had already converted to working and using material in an online space. Critical to creating the products was the workflow, which was digitised relatively quickly, and libraries, as the main customers, had already evolved into highly computerised spaces so could migrate to digital products quickly; this meant that print has become less important for users. As early as 2005 online revenue for one publisher surpassed its print revenue; for another, print titles are simply print on demand now.

The open access challenge

Ensuring research is freely accessible over the internet has become an issue that journals publishers are increasingly having to face, the remit to disseminate becoming more compelling now that it easier to achieve. Copyright systems have evolved seeking to further enable the electronic dissemination of research (as we will see later in this chapter and in Chapter 10) and open access has become a key topic for debate among scholarly publishers and research institutions.

One element of this has been the growth of self-archiving. Institutions have developed their own archives where their researchers lodge their work. There is a register of open access repositories of this sort. These institutional repositories may well have self-archiving mandates ensuring that their researchers must archive work undertaken while working for that institution. There are various organisations that are involved in this aspect of open access, ensuring continued access to these archives is available.

In theory, therefore, research like this is openly available and anyone can access it for free. But, as we have seen, peer review is important for journal articles. Articles cannot simply be lodged in any form without some sort of assessment of quality and accuracy. Here, therefore, remains a barrier to research being openly available immediately. Some sort of peer review needs to take place. In many ways this becomes the critical arena where publishers can add value. Where self-archiving happens, the actual article does not have to be the final version, as might be produced by a publisher, but does need to be post the refereeing stage, so it could, for instance, be a final draft before it is officially published; this is important as it still allows for a publisher to play a part of the process even where there is self-archiving. The fact the material is free at some point in its life cycle goes some way to answering those who suggest that research needs to be available for all to use and benefit from.

Open access models

Self-archiving is only one element of the picture. Open access has developed along two main lines: Green Open Access (green OA) and Gold Open Access (gold OA). Green OA is essentially the self-archiving outlined above: it is important to note that the repositories used can also be centralised (such as PubMed Central) and there are many well-established ones that are not necessarily associated with a particular institution. The issue of green OA is evolving, and in some cases, where a publisher is involved, green OA can refer to journals where a subscription is paid for access to material for a certain amount of time before it becomes available for free. Gold OA essentially refers to an open access journal that is available through a publisher’s website. The publisher manages the journal but it is open access at all times and so all articles are available free to all users. It may be that they receive a fee for managing a journal on behalf of a learned society which covers costs to enable the open access, or individual authors or their institutions contribute to the cost.

The challenge has been for publishers to look closely at these models and see how they can still be involved, not just from the point of view of the peer review process but as part of the academic drive towards increasing accessibility, while maintaining some commercial viability. So, for instance, hybrid open access journals will have parts of the journal only accessible via subscription and others that are open access (obviously something only possible for internet journals, where various access controls can be set up to manage this). To fund the open access parts of such journals the author has to pay (or more commonly their institution) if their article is to be open access. This leads to the issue that again the research is being paid for twice – once by the institution which funds the research itself and then again for it to be disseminated. For leading journals, which can be expensive to maintain, a hybrid approach can provide an option for authors to be published in those key journals while fulfilling any open access remit their institution may demand. Publishers can maintain the quality of the journal with these different revenue streams.

Publishers have developed a further model to marry a commercial journal with the remit to disseminate it. For certain non-open access journals which are paid for as usual by subscriptions, licences or pay per view on an embargo basis exist so that articles become open access after a certain amount of time, commonly six to twelve months. Given the speed with which research moves in certain disciplines this can be beneficial to publishers, who maximise this commercial viability up front; by the time research falls into the public domain its value is much decreased. However, with the obligation for research to be available to researchers this model can be contentious as key research cannot be accessed easily or freely until it is becoming out of date.

To develop these hybrid models further publishers are focusing on the concept of serving the author’s needs; if authors pay for their material to be included (subject to peer review), rather than simply self-archiving, they can get a wider service from the publisher. For some journals authors can choose the level of involvement, the tiers of accessibility; so, for instance, Springer offers a menu of open access options for a selection of its journals.

There are several benefits publishers can bring to authors over the self-archived systems, including:

- the ability to track citations

- interaction with a high-quality review process

- help in managing their rights effectively

- protection against piracy

- marketing, keeping the profile of the journal high

- effective sales activity, also improving the profile

These last two points are important – keeping a journal’s profile high plays a critical part in ensuring wider dissemination of research; these journals, actively and continuously promoted by publishers, may well be much better known than an institution’s own archive.

The problem remains with these systems, however, that the peer review process has to be paid for somehow. Not only that, the cost of running journals is expensive because of the technological infrastructure, which needs to innovate continually to provide accessible, easily searchable content across an endlessly increasing body of work. Institutions looking to move away from formal journal arrangements with publishers can find themselves debating the cost of setting up and managing their own easily accessible archives; they may well end up paying a third party to maintain a CMS for them, in which case they have not necessarily moved very far away from the published route.

But there are attractions to rethinking the way journals are managed, particularly in relation to speed. Currently the peer review process is not necessarily speedy, which can delay important time-sensitive research. Authors publishing in journals have to undertake more detailed editorial work, delaying them when they could be concentrating on the next stage of their research. When speed is of the issue can the current journals model really fulfil the researcher’s needs? Articles are not in essence any different from the printed version; some interactivity may be of more benefit to the process of research.

While some of these institutions are exploring alternative ways to manage the peer review process, publishers too are having to review each stage of the journals process in order to innovate and satisfy some of these key issues. They need to add value to ensure their well-established publishing mechanisms remain critical to the academic community. Keeping ahead at managing aspects such as citations, impact factors, etc., building premium services with alerts, bulletins, etc., and marketing effectively are important parts of what a publisher can offer.

Governmental drive to more open access

As the debates and business models around open access evolve, there is a growing momentum in the public sector to force the move to open access. Government-funded research projects are increasingly including a requirement for researchers to publish via open access. The EC is currently considering a proposal of this sort with its £64 million research funding programme; pilot schemes and extensive consultation are underway to explore it. The Working Group on Expanding Access (the Finch Committee) in the UK is another example of a government examining the process of publishing academic material; in this case the working group is conducting a review of the way open access could, and possibly should, work for the dissemination of research, further defining the green and gold academic approaches. Green open access is beginning to become a firmer concept whereby green journals can charge a subscription for a limited embargo period with a defined length of time, currently subject to debate; the gold system is in many ways preferred by publishers, who will gain some sort of funding via the research funder, and so make the material available on open access from the start; research funding on this basis would therefore need to include some allowance to cover the cost of dissemination. These debates will continue and the scholarly publishing industry has consistently to establish the importance of its work within the academic community.

The monograph: the scholarly publisher’s next challenge

We have looked at the key developments and current challenges facing the journals publisher, but the issue of digital environment for monographs has yet to be tackled as fully as for journals and the industry has been turning its attention to this area more recently. Monographs as a type of published research work have, over the last few years, suffered a decline. Academic libraries, facing the pressure to spend increasing amounts on their digital provision of journals, have made savings by cherry picking more carefully titles for their monograph lists. Academic presses therefore have had to respond in various ways, whether turning their main focus to textbooks or supplementary books that may have a longer shelf life in paperback or reducing their range of topics in order to consolidate on a particular discipline and build expertise there. University presses, which were responsible for considerable monograph output, particularly in the US, have often been put under pressure to become more commercial and have had to reduce their monograph output despite their remit to advance research through publishing. So the market in print form is declining and both the numbers of titles and the quantities printed have reduced. So what impact can the digital environment have?

Print on demand

One solution to the problems monograph publishing faces that has emerged with the advent of digital publishing is the ability to print on demand. While just in time printing was already developing for short reprint runs, the digital environment makes this even easier to manage. Academic publishers were accustomed to building up dues on a title until the numbers reached a sufficient quantity to make it worth reprinting. Libraries had to wait for a reprint, but usually, if they wanted to fill in a gap in their collection, were willing to do so in order to receive the title eventually. Now print on demand is so flexible it can be put in place for every individual who asks for a single copy of something at the point they ask for it. This has not had much effect on the monograph price for the library but does mean that publishers can save money on stock holding and management, and, as such, keep some monograph publishing alive (and indeed supplementary text material) which it might otherwise not be possible to maintain. Print on demand exists for other sectors too but it has arguably been most fully integrated into the workflow of an academic house, and often purchasers may not know if a title has been designated print on demand when they order it.

Increased access for monographs

Researchers see great opportunities in being able to access monograph research material. Mass digitising of books such as Google has undertaken has helped to develop an expectation amongst researchers that they can access older material that previously may have been difficult to find; this has been important for driving usage in research monographs, and participation in book search initiatives like this, which aid discoverability for specialised titles, has been of benefit to some publishers in growing sales of their own titles. It increases the long tail of the monograph. For authors too it is significant as it increases discoverability of specialist works, so increasing the potential for wider dissemination.

Problems for the monograph

The main problems for a digital monograph programme revolve around:

- the archive – the length of time and cost required to build an archive

- different purchasing patterns for a library – the change from an individual purchase to a subscription service

Creating the archive

Creating ebooks for any new titles does not in principle create a problem: digital workflow for new titles coming in is well established. Monographs are available and marketed individually in ebook format and can slot into a library’s own e-resources catalogue. However, the older titles, the important backlist, may remain in print form only. We have seen above that the book has taken longer to adapt than the journal to the digital environment. There are digitisation challenges for the longer form of the monograph, which short journal articles do not face. There may be more complex issues of consistency across the text, and effective searching across longer pieces of work and the ability to ‘chunk’ books is challenging. A monograph is less likely to be standardised across the whole list, but rather designed to have stylistic integrity within itself.

The creation of an ongoing digital archive, due to the longer development times required for a book, is slower than that for journals, while the cost of digitising large numbers of older titles is expensive, particularly given the lack of standardisation across titles. Different production methods used throughout the last century lead to a variety of different approaches needed to turn the book into digital format. The archive frameworks for storing and presenting digital monographs are also not as fully developed as the digital environments for managing journal articles. Different publishers have different approaches to digitising older monographs. One will take the view that if it is asked for a digital version that is the prompt to produce one. Others are taking a systematic approach to developing an archive. Sometimes the only record of the book is the print edition itself, which then needs to be scanned and verified. This covers titles that are held by the publisher and still in copyright. Google’s involvement in mass digitising of archive titles is covered in the case study in Chapter 10, but it too has found issues with regard to the quality of the texts it has scanned in, and has tackled the need to verify text that may be unclear from simple scanning in different innovative ways.

The sales model for electronic monographs and portals

There are problems in the sales models too. The availability of ebooks does not mean that libraries will purchase them; libraries will be making decisions as to whether the cost of paying for access to ebooks is worth it, with different criteria in mind from their decisions with regard to journals, where their expectation of migration from print is further advanced (if not complete). Selling packages of journal subscriptions is more effective in terms of sales effort than the selling of an individual book in print or in ebook format, so the market here is less developed in comparison: titles tend to be selected individually, or in small batches, and the purchase once made is not reviewed as it is a one-off payment. Nor is the cost of an ebook monograph going to provide much saving for a library – the cost of the book as a whole still needs to be covered (royalties, marketing, etc.) despite some savings on physical printing and distribution. While for textbooks the availability of an ebook is of more use to a library in providing online access for a number of users at once, this is less critical for often highly specialised research books, which may be of relevance to only a few users.

Meanwhile, for archives, the pricing and the range of content available can prove more problematical than for journals in that libraries may well be expected to pay a subscription to products they previously bought individually for a one-off price, and so owned within their own print archive. Converting libraries to a different business model therefore makes this a more difficult project for publishers and does depend on them being able to offer a comprehensive list as well as depth of output within particular disciplines. However, despite these hindrances, the move is clearly towards more electronic delivery of these products and the sales model is beginning to adapt.

Book-based services and adding value

Publishers have started to create more complex digital products. They have taken a similar approach to journals in that the focus on new product development has been in developing portals to access an archive of digital book content. Similar benefits to journals portals apply, such as the ability to search across a range of titles and pinpoint relevant material within a book. Integrating these with the journals databases too makes a compelling offering. For smaller publishers there are opportunities to join groups in order to make their publications available: Oxford University Press and Cambridge University Press both have programmes of this sort gaining a level of critical mass. Some of the large aggregators offer such services as well, such as Dawsonera or MyiLibrary, set up by Ingrams and ebrary; these may include an element of ebook and document management services for libraries to maximise their book collections.

Yet the creation of a database of content is potentially an important strategy for academic publishers; as with the journals industry, the value that publishers hold is exactly the fact that they have a large database, continuously evolving, which can be used in different ways, flexibly and future proofed. Putting book content also into a database and treating it almost like a raw data set may be the way to ensure monograph-style material can survive. Making it easy to reuse in different ways (for instance linked to teaching resource material in the form of textbooks or put together in different ways to create new collections) may be an important part of keeping the material live.

For some the development of digital publishing programmes for scholarly books may help rejuvenate the monograph. It can help this declining market in various ways:

- books can live on the long tail and still be accessed when needed, continuing to build citations where journals may well not

- authors will get more discoverability in searches – books can rank as well in citations on Google Scholar as journals

- cross-disciplinary learning can take place much more easily, particularly for more book-based disciplines

- there is wider access to titles beyond the research community

In the longer term there will be increased convergence between journal and book publishing as they will be increasingly integrated.

Future directions: problems and opportunities

Declining budgets

While an onlooker may have considered the digital environment to be one where libraries could save money, as publishers were saving print and physical distribution costs, the key benefits of online access – those of timeliness, accessibility and discoverability – have come at a cost. Though they should be able to increase the value they get for their spending, libraries are rarely able to reduce budgets in any significant way.

The scholarly market faces one main problem around which there are many issues: research output is increasing but library budgets are often flat or decreasing. In some global markets there will be growth, but in the majority of western economies, where research continues to be extremely active, there is increasing pressure on libraries. As the research communities continue to evolve, so increasing specialisation (especially in the scientific arena) requires more specialised journals, thus increasing the number of titles a research institution needs to purchase. This pressure on budgets is not going to go away.

Are publishers necessary?

We have also seen the challenges that publishers face in the light of issues such as open access. Publishers have to justify their role in scholarly publishing and show why, even in the changing environment, they remain critical to the arena. Issues around quality and prestige clearly play a part in this as publishers have developed highly effective processes to manage research. Investment in sophisticated search engines and data warehouses also plays a part. Many publishers also own many important journal archives, which will always make them important players.

However, sales and marketing activity is also key to what publishers can offer. Maintaining the prestige of a journal is important as more journals are developed: the competitive edge of a title is critical to its continued place in the market. Institutions doing their own archiving may find it difficult, and certainly costly, to continue the sort of marketing presence a professional publisher can provide. Learned societies may very well value a publisher’s marketing and PR investment and expertise highly as a way to ensure the profile of their society is preserved; that way they can continue to attract excellent contributions and so maintain their prestige. In the battle over which journal’s portal dominates, it can be important for a journal that is establishing itself to be accessible and searchable via another key title with that publisher. As publishers develop more integrated platforms (developing integrated books/journal material) authors may also find they want to be part of that.

Philanthropy

One important area that has improved is internet distribution to markets which previously would have found research difficult to access. Developing economies have in the past benefited from various schemes to allow for production of cheaper versions of print products to ensure they can still access research that may be critical for their continued development. However, a physical product still has limitations and full costs that cannot always be subsidised, while online some of these barriers to wider distribution are removed. Various organisations have a remit to ensure research can be accessed by poorer economies, and the proliferation of these in recent years has been a reflection of the ease with which material can be managed in an online environment. Selected journals can be accessed in different ways, and these may involve reduced or no fees for users. For instance, the Hinari programme set up by the World Health Organisation (WHO) enables organisations in developing countries to access health and biomedical research; it works alongside similar organisations focusing on different disciplinary areas, like Access to Global Online Research in Agriculture (AGORA), Online Access to Research in the Environment (OARE) and Access to Research for Development and Innovation (ARDI). These and other organisations are building important relationships with research publishers.

Future research models with public peer review

We know the process of peer review will be an issue that challenges the academic community and there are examples of open access journals that are looking at ways to manage this without the involvement of publishers. These stem from various motives. They are not just a way to manage peer review with a reduced cost base, nor is re-engineering the review process simply a way to improve speed to market; but they also embrace some of the democratic ethics that surround the internet with what is called public peer review. There are examples of journals applying a more interactive peer review process which allows for mechanisms of continuous reviewing and updating until a final article is approved.

What this means is that articles are posted up in a very early stage, with the understanding that they may not be tried and tested fully. Official referees will be designated to review a paper but other people may contribute at any point as well as make use of some of the findings if they choose before final peer review. They could be posted as discussion papers only. This in effect tries to combine a conference and journals approach, allowing for online discussion of material that may lead to improvements of a greater degree than would be contained in a traditional peer review environment (which broadly works on one draft at a time with less ongoing input).

The argument is that this allows for the maximum amount of input and the finished work may be much better than it would have been; the research itself started its journey into the community at the earliest possible stage, allowing for fruitful development by others. Authors too feel the pressure to submit better work as it will be viewed publicly at the earliest stage. Of course there are also criticisms:

- there may be problems with the motives of some of those who review documents

- the potentially competitive nature of the discipline may distort the process

- there may be problems where people cannot distinguish between good research in progress and research that will not ultimately pass the process

- inadequate research may start to be used before it has been properly reviewed

- the final article may never quite be fully formed and finished off

There are ways of managing these issues, but they may require more cost. However, this represents a slightly different approach to research that may be a threat to publishers unless they move forward.

For publishers to withstand these sorts of pressures they need to maintain their relevance to the fast-moving arena in which they operate. So where next for academic publishing? When looking at the future there are a number of directions publishers are exploring and new debates that are surfacing:

- New sales models will be developing around more specific understanding of usage and the experimentation around the open access arena.

- There may well be new ways of working as users interact with systems and the line between writer, contributor and user becomes more blurred.

- Strategic reading/data mining/data access will customise products further – as customers get more access to the raw data warehouse and only take what they really need.

- Content may also change – the individual journal issue may well disappear entirely and the ongoing nature of the review process can be interrogated and accessed throughout the process.

- Sources of content are likely to change, with BRICs economies increasingly providing content as well as buying it. Many companies have had sales and marketing sites across Asia, for instance, but editorial offices are growing in number too.

- A particular advantage of the internet is that definitions of book and journal articles can change – a piece of academic work can be any length and not limited to a traditional article or book format, so the opportunities to publish material in whatever is the most appropriate way are opening up. Publishers are moving to offer spaces for researchers to publish material that does not have to adhere to a predefined length or format (such as Palgrave Pivot).

- Continuous product development will need to keep pace with technological developments – product development will move on from search and archive to making content useable in different ways – using, for instance, the semantic web to draw connections, linking data and extracting different sorts of data such as diagrams.

- Adding value will need to become more sophisticated as users become more accustomed to expecting certain features as standard (such as email alerts) rather than as add-ons.

- Version control will become critical as there will be increasing time sensitivity around access as research moves into the public domain.

- Integrated platforms will emerge as there is likely to be increased convergence between journals and book publishing as they use the same systems.

- There will be more integration with the wider internet via search engines and a more seamless route to the content.

- Access issues will remain key – ubiquity and mobility. It is not just about accessing content from where you happen to be (e.g. via mobile phone, which will require reworking material to make it useable in small-screen formats) but accessing it from what you happen to be doing; in this way research becomes embedded into the tools you might use.

- There will be increasing debates about economy of attention – how long is information used for? And how long does it have value? Or how does that value change in terms of its longevity?

- Measures of usage will change as libraries look at new ways to assess the value of research products to their work.

- Business models are continuing to be developed outside publishing (e.g. from academia itself, from crowd-funding).

- Public sector pressure on access will also continue to force the sector to make information freely available.

- Timeliness will also continue to be an area for improvement as research gathers pace and readers expect less and less delay.

With all these we come back to the central tenets of research – timeliness, accessibility and discoverability. Ultimately publishers will need to ensure they remain ahead on these key areas in order to maintain their position. The relationship between publisher and academia will remain a special one that will need to continue to evolve and change as the digital economy develops.

Books

Campbell, Robert, Pentz, Ed and Borthwich, Ian (eds). Academic and Professional Publishing. Chandos, 2012.

Clark, Giles and Phillips, Angus. Inside Book Publishing, Routledge, 2008.

Cope, Bill and Phillips, Angus (eds). The Future of the Academic Journal. Chandos, 2009.

Mincic-Obradovic, Ksenija. E-books in Academic Libraries, Chandos, 2010. Thompson, John. Books in the Digital Age. Polity, 2005.

Websites

Some examples of journal portals and open access sites:

ejournals.ebsco.com – for journals sites

www.credoreference.com – for journals sites

www.dawsonera.com – for ebook aggregators

www.doaj.org – for journals sites

www.ebrary.com – for ebook aggregators

www.ingentaconnect.com – for journals sites

www.jstor.org – for journals sites

www.myilibrary.com – for ebook aggregators

www.plos.org – for journals sites

Examples of p blishers:

online.sagepub.com – for publisher’s own site

www.alpsp.org/Ebusiness/Home.aspx – for other relevant organisations

www.jisc.ac.uk/aboutus.aspx – for other relevant organisations

www.springerlink.com – for publisher’s own site

www.stm-assoc.org – for other relevant organisations

www.wolterskluwerhealth.com/pages/welcome.aspx – for publisher’s own site

- What are the benefits for a learned society of continuing to work with a publisher?

- How can a publisher resolve the question of critical mass in relation to the development of a digital service where they might have strengths in some disciplines and weaknesses in others?

- Can publishers help libraries manage budgetary issues?

- How might publishers balance the need for stable revenues and profits with the costs of investing continually in publishing technologies?

- Some experts foresee a further consolidation among the key industry players. What problems might that pose?