Developments in digital publishing in the education market

In this chapter we will cover:

- The educational publishing context, outlining the background to the textbook markets at both schools and higher education (HE) levels with reference to the differences between the UK and US markets

- Characteristics of the schools market in terms of publishing and development of classroom technologies and learning resources

- What current digital resources for schools look like and the challenges they face as the business model develops

- Current developments in digital resources at the HE level, with developments in e-learning

- The e-textbook for schools and HE markets, including a look at the iBook textbook

- How educational publishing houses are developing digital assets and the challenges they face going forward

The education market quickly recognised the potential in the advances in digital technology for presenting an exciting and interactive teaching and learning environment. However, this market is a much more price-sensitive market than some and so it is a challenge to build digital products that are comprehensive in their application of technology while cost effective. Schools cannot spend a large amount of their annual budget on digital resources, which also require significant investment in technology; students, who are the purchasers of texts in the higher education market, are often burdened with course fees and living expenses, which means that they have little left to spend on textbooks. Yet to make the texts visually enticing, truly interactive and significantly different from a print book is a costly business. One of the biggest problems for publishers is how far the print and digital products remain linked and reflect each other. Pedagogy would suggest that digital products could and should be significantly different from a textbook but this transition is a difficult one for publishers, and indeed teachers, to make.

This chapter will consider these challenges and explore how far the industry has moved towards transforming itself into a more digital-based business. It covers the characteristics of the markets and the development of technology within the classroom in order to understand the environment for digital products. Looking first at the schools market it describes how the industry has developed products, exploring some of the key issues publishers face here. It then looks at the issues around developing e-textbooks in both the schools and HE sectors, including the opportunities and threats surrounding Apple’s focus on the education market. While some issues are similar across both schools and HE markets, a further section explores some of the distinctive products available to students and the changing approach publishers are taking to the sectors. Finally, it looks at some of the future directions for the education market as a whole.

Context: introduction to the textbook market

Textbooks in the US and UK markets

When looking at the area of education there are various distinctions to bear in mind. In general the focus of this chapter is on schools publishing. However, education publishing can encompass the production of textbooks for HE and academic audiences. These are sometimes dealt with within the context of academic publishing, at other times as part of educational publishing. Because the focus is on the type of book, i.e. a textbook to be used as part of day-to-day learning, both schools and HE markets will be considered in this chapter. This section explains some of the characteristics of these sectors in the US and UK.

Schools and HE textbooks: the US market

It is important to understand the differences between the UK and US because publishers have to adopt different strategies for each, even global companies such as Pearson. This can influence the way digital products are developed. The US market operates differently from the UK one in both the schools and the HE textbook sectors. Textbooks in the US can command large markets at both levels and, since companies are playing for high stakes, the cost of developing texts in a highly competitive environment is considerable. For both sectors the development process for the book is detailed and extensive; the production is costly as textbooks are long (in order to cover as much as could possibly be needed and so to be a one-stop shop) and are generally published in hardback and full colour. A market-leading macroeconomics text for university students can cost around $150, while a school text can cost $50. The structures in place to sell these books are highly organised as sales people focus on claiming large-scale adoptions; and the costs of texts, whether borne by students in the HE market or institutions in the schools market, are therefore exceptionally high. As we will see, technology has played a part in the ability to supply interactive and multimedia materials to add value around the core text in the form of resources that are used by teachers and students. Nevertheless the cost of these has to be covered in some way by the book itself, so prices continue to be very high in the US market at both the schools and HE level.

The effect of adoptions for schools and HE

Various mechanisms around adoptions exist as a result. In schools it is quite common for texts to be chosen at state level, and so for the successful text an extremely large and guaranteed market exists. For this market the result is that the cost of books is high as publishers aim to produce the most comprehensive and enriched textbook they can in order to win the adoption. So the cost of investing in a set of textbooks to use for a course in school is considerable. Therefore the books schools use often have to last for a long time, which means at the end of their life they are often out of date – something that becomes significant when looking at the potential for digital products.

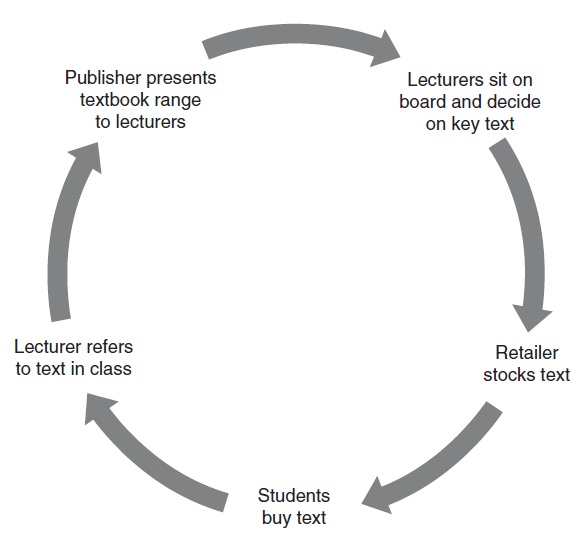

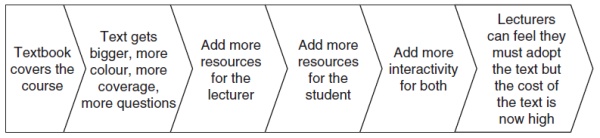

In universities lecturers sit on boards to select the key texts that are to be used and there is generally a high expectation that students have to purchase them in some way or other. The challenge of the adoption is that the publisher must persuade the lecturers to use their text, but it is the students that must actually buy the text. As Figure 8.1 shows, the student, though the main customer, is only a small part of the cycle and often the one most distant from the publisher’s sales effort. As publishers at both levels compete to win what can be a large adoption, the books have become enhanced first in terms of production quality and comprehensiveness of content, then with a variety of other products and services that support students or teachers. Figure 8.2 illustrates the constant developments required to keep competitive. To cover these developments the cost of the books increases, but for lecturers who have got used to choosing full-colour texts with all sorts of additional web-based resources it is difficult to go backwards; they aim to choose the best for their students and that usually means the biggest and most comprehensive book.

At the HE end of the market in the US the result has been the development of a sophisticated used books market which enables students to realise some of the value in the book once they have no need of it. It also allows bookshops to engage in a secondhand market which holds higher margins for them than new textbooks. In order to preserve sales the publishers have responded by putting pressure on new edition cycles as the first-year sales of a new book are more critical to make up the costs of producing the book; previously second- and third-year sales were more significant to making profit. There is also a book rental market where books can be rented for a semester: Amazon, for instance, do this in the US; a student can then have a new book, but pay a much smaller price, returning it at the end of their course.

As the price is so high lecturers are also aware that value for money is important, so customisation or course packs become attractive as users get exactly what they need rather than pay for material they are not going to use. Companies specialising in putting course packs together, where lecturers can use materials from a variety of publishers, have developed in this market. Similarly, publishers have found it useful to create libraries of material so that they can then offer, for instance, a bank of case studies from which lecturers can pick and mix. Here again, one can see opportunities provided by digital publishing to allow for further customisation.

It is in the US market that Apple has focused its attention on the launch of its iPad-based textbook programme for both higher-level schools publishing and the introductory end of the college and universities market; one of Apple’s tenets is that the average US textbook is simply too expensive and yet is failing to do what is needed to provide a good and effective learning experience. We will look at this in more detail later in the chapter (p. 102).

Schools and HE texts: the UK market

In the UK and European markets these issues still exist but they are much diluted. As the markets are much smaller and the money within the market is less, price sensitivity is a more critical driving force in the sector. On average textbook prices are much lower; the same macroeconomics text adapted for the UK market may cost £37, while a schools text that may cover more than one year of a course can be around £17. The pressure on winning adoptions is still there but less so than in the US as the financial stakes are lower, and though sales activity does focus on trying to promote adoptions, there is not such a formalised way of approaching these at either schools or higher education level.

Schools

The UK schools market is not driven by the adoption culture in quite the same way as in the US, though of course it exists; groups of teachers will adopt a text that can be used across classes and levels by different teachers at different times to ensure consistency of approach. However, the prices of books are considerably lower than for the US market and there is a more adaptable approach to the mixing and matching of textbooks (particularly at the primary school level) within the classroom, though, in general, the drive to pass particular courses is central to the development of any textbook programme. The books may cost less but schools budgets are also lower, so winning an adoption is still a critical part of the sales process for a publisher. Well-designed and comprehensive support materials remain an important way to attract an adoption; some of these are expensive, and detailed teacher guides to delivering a course based on a certain textbook are sold alongside the student packs, but there will also be resources available for free.

HE sector

In the case of higher education, while lecturers may recommend texts and, in some cases, work very closely with them in the course of their teaching, the choice of texts tends to be reasonably individual in comparison to the US; there are also somewhat lower expectations that the students will need to have their own copy of the book. With smaller class sizes compared to the US it can be easier for a student to keep up with their studies without extreme dependence on a book. Clearly there are some subjects that are driven more by the need to have textbooks than others, and in the social science and science arena set texts are still particularly important, but the prices are much lower than in the US, even for textbooks adapted from US courses for a UK/ European market. Support materials are provided, though on a much smaller scale than for US texts; they are broadly free, however, in order to attract adoptions.

HE courses in any case are structured differently, with less emphasis on large numbers taking similar introductory courses before specialising around specific subjects. In the UK students tend to study a more focused programme of topics around their subject area rather than take some general courses before specialising; courses from the first year can therefore be more varied than is often in the case in the US, where students across a whole campus may all be doing similar course choices in their first year. There is also a greater likelihood of academic publishers in the UK who publish monographs and journals also producing textbooks for university markets; in the US key textbook publishers tend to have consolidated in the HE textbook market.

So it is useful to bear in mind these distinctions between schools and HE market as the drivers in these markets are slightly different. Some aspects of these markets are similar: for instance, in both the UK and US schools do not always have the resources to invest in the hardware needed to support the digital products. However, there are also some differences. The price issue between the US and the UK is an important one which makes the introduction of the Apple textbook product more critical to the US market (see the case study on p. 102); but the US market can command higher investment in digital products as the financial stakes are higher.

Characteristics of the schools market for publishing

In order to understand the reasons why digital publishing has developed for the schools market in the way it has it is important to note some the drivers of the market in general. In the development of digital products there are two important facets to the schools market:

- the curriculum – which drives any sort of publishing for this market, both print and digital

- the technology – which provided the infrastructure to develop digital products within schools

The curriculum drive for publishers

Key to the development of textbooks for the schools market is the curriculum. In primary school in the UK this is focused on the development of a national curriculum, for which books do exist but which can be used flexibly, interlinked with the teacher’s own materials. The particular focus of the curriculum is literacy and maths. Literacy programmes in particular are big business for publishers, as using printed books is central to the teaching of reading in the early years: developing reading schemes can take up to around 50 per cent of a primary publisher’s budget, for instance. As educational pedagogy changes, different emphasis is given to different aspects of primary teaching, and so products suited to these new pedagogical trends have a role. For instance, the use of phonics is, at times, more central to the teaching of literacy than at other times (when it is used alongside other literacy methods). Educational software companies are also active in this market, producing programmes that can be used to individualise teaching for each pupil or to reinforce learning; as long as there is access to the technology these can be used alongside teaching with texts. As teacher’s own materials play an important role in teaching at primary school, publishers also focus on producing resource packs (anything from photocopiable sheets for spelling homework to online music resources for non-specialist teachers) that support flexible teaching within the classroom.

By secondary school in the UK the national curriculum continues and introduces more subjects: students will generally use textbooks that follow each subject, sometimes designed to build into a three-year programme which takes them through the whole subject up to age 16. There will be areas where teachers can make some selections as to which topics to cover in more detail (e.g. history topics or English texts). From age 14 the curriculum is superseded by the detailed specifications set up by exam boards for each subject leading the GCSEs at age 16. Teaching at 16–18 is completely determined by the specification being followed, whether academic (A levels) or vocational (BTEC or OCR National). This is similar for qualifications in a further education framework or for various vocational qualifications that are available at various ages. So from this one can see that the focus on curricula is important for publishers in this market, and especially the focus on exam board texts.

The trend in the UK has been for more exam-specific texts to be produced. The boards often put up for tender the opportunity to be the main publisher for a particular course book. Edexcel is an example of taking this further: Pearson owns this exam board (part of its remit is to become a key player in the area of assessment globally, which we will touch on again on p. 106) and so Edexcel textbooks tend to be produced by Pearson, though Edexcel will endorse texts by other publishers. This specific arrangement may not last, but the principle is that if there is an exam board text, then teachers have to be reasonably confident of other texts if they decide they are not going to use it; and if they are anxious to ensure that they give their students the best outcome and that they do what is needed to pass, they can often feel they need to adopt the endorsed text to be safe. The advantage of such texts is not just one of focusing very closely on the sorts of questions students will face, but that they represent value for money for the school in that it buys a text which only covers what pupils need to know – i.e. it is not paying for extraneous material that is not required learning. Even where a textbook is not endorsed specifically by an exam board (and some authors are so well known in their own right that teachers will still use those texts above an endorsed one), resources mapping the text onto a specific curriculum are provided. So as exam board texts drive the schools publishing at that level publishers inevitably enter the new edition cycle as driven by the exam board. When the exam changes, the texts will need to change, which requires investment from the schools to buy into the new texts. Even for those levels which do not have exams, the push to keep renewing texts in order to get the most up-to-date one is still important.

Teachers’ resources are also important at the secondary level, with books covering a range of support materials such as printable resources, lesson plans, practical exercises and assessment activities in print and online formats. The thrust of much of schools publishing is around the development of a ‘course’, often branded, as a group of textbooks that work through each year, together with support books (maybe working on skills) to supplement each stage and teaching resources in print and online. Pedagogical thinking around learning styles, flexible teaching and ways to cater for different levels go into designing these courses, so schools will often have to buy into packages and be sure that they can get their full value out of their investment.

Blended learning, the mix of styles of teaching and learning from face-to-face to online support, has played a part here; the curriculum now includes more digital requirements (partly in order to ensure increased access to learning), so digital support has become a more integral part of the overall adoption of a textbook. The trend to more blended learning is going to continue and materials are set to become more sophisticated in order to support the digital learning environments, which may well be accessed remotely (and independently) rather than in the classroom with teacher support readily available.

Changes in government policy have a considerable impact on the development of textbooks. So, for instance, when the UK government decided that phonics was the only method to be used for teaching literacy for 5–7-year-olds, it had the effect of changing the market. Publishers had to spend money developing new texts (maybe having wasted money on developing schemes that could now no longer be used), but on the positive side money came into the market to help schools buy new books: the market for reading schemes in this particular instance grew by 75 per cent. The problem publishers face is that government policy can change, and even reverse, on a regular basis and second guessing policy in order to future-proof a publishing programme is a thankless task.

Technology in schools

Technology has been prevalent in schools for some time now. A drive in government funding in the mid- to late 1990s in the UK ensured that technology was integrated into the classroom. This revolved around increasing access to computers and building more IT suites, replacing blackboards with interactive whiteboards and ensuring increased internet access.

Two organisations played a particularly important role in the development of technology within UK education:

- BETT

- BECTA

The British Educational Training and Technology Show was founded in 1985 and is now known as BETT; it is an annual exhibition and trade show which showcases the latest educational technology. It also presents awards for the best-quality teaching resources that make excellent use of technology in the classroom. While it is generally dominated by educational software providers and also covers hardware and IT solutions, publishers do win these awards for their digital teaching programmes.

The other influencing body in promoting technology in schools was BECTA (originally British Educational Communications and Technology Agency and now dissolved), which was set up in 1997. This organisation was set up by the government to ‘lead the national drive to ensure the effective and innovative use of technology throughout learning’ (www.education.gov.uk/aboutdfe/armslengthbodies/a00192537/becta). BECTA undertook various roles, which coincided with the increase in government funding to schools to develop their IT capacity. These advisory roles included working on projects to help embed the effective use of technology in the most coherent, cost-effective way within schools, encouraging the market to develop appropriate and effective teaching and learning materials to promote the development of IT, as well as share best practice and ensure value for money. This organisation now no longer exists as government funding ceased, but it was very influential in the development of technology for schools.

Also in the late 1990s and early 2000s there was a significant increase in government funding to bring technology into schools and particular efforts were paid to starting the development of digital content for the new technologies. Initiatives were developed, with considerable funding, in order to deliver a digital curriculum. BBC Jam is an example of an online education service; it was launched in 2006 with a budget of £150 million. This was subsequently closed by the BBC Trust due to issues over fair trading. The Harnessing Technology Grant, which set aside £2.5 million for schools to support digital projects of all kinds, was another example of funding opportunities, but this was subsequently cut by the Coalition government which took office in 2010, which again highlights the problems a publisher can face in this marketplace.

Nevertheless, taken as a whole, access to the technology became much easier through these initiatives, allowing publishers and other suppliers to develop digital products knowing that they could be adopted very easily within schools. Interactive whiteboards (large, touch-sensitive white screens that link to class computers and can display material, connect to the internet, etc.) were one area of focus for publishers as they were quickly adopted across the schools sector with the injection of funding. Publishers quickly produced materials and resources for use on these, building on their print programme of teachers’ support materials. These materials were also suitable for virtual learning environments (VLEs), which provide a web-based interactive space for students and teachers to access, collecting together various resources, learning activities and student support. The increase in the number of computers in schools was also important and education software companies have also been active in this area; publishers may own, or work closely with, software houses to produce materials that students can use to develop their own learning at their own pace.

Background to developing multimedia in schools

With the growth of technology in schools the main focus of product development in the first instance was around supplying teachers with more materials to use on those systems. Publishers aimed to provide additional resources to be used in the classroom to support print texts, but this allowed for the development of interesting and interactive learning packages that exploited the benefits technology could provide.

CD-ROM was the precursor of the online product and many sophisticated CD packages were developed that could be loaded onto a central network within schools and used to support lessons. These tended to involve additional resources and links to the web for teachers to back up their use of the texts. These were then transferred into the online environment, not always an easy process, to form the early web products, around which more sophisticated products have grown.

Features and benefits

It is reasonably easy to see how the digital environment can enhance learning for pupils. The sorts of features that can be added into a multimedia product include:

- video footage

- audio

- animated diagrams and figures

- links to websites

- links to web-based resources (e.g. maps, images)

These features clearly add interest to a subject and mean students can access learning through diff rent media according to their own learning style.

Teaching can easily be made ‘more alive’ with the integration of a variety of different resources, but there were additional benefits in the flexibility to tailor programmes in various ways. For instance, digital resources can allow for:

- flexibility for teachers to adapt their teaching programme

- customisability – so that teachers are not constrained by the pedagogy of a text

- built-in add-on resources for teachers

- built-in assessment for teachers

- marked assessment (i.e. multiple choice)

- homework options

- independent work options

- the ability for students to progress at their own rate

- more flexibility to cope with different learning levels, including special needs

Overall, the opportunities provided by the digital environment can enhance the education experience.

What do the digital products look like?

The first products did not aim to tackle the issue of ebooks for use by individual pupils, but they focused on ways of enhancing the use of print texts within the class. This has continued to be the trajectory on which products predominantly have developed, cost and access to hardware being the main limitations for developing individual e-textbooks. However, the benefits that the digital environment brings have been embedded further into the products in terms of flexibility and customisation by publishers. They will, for example, take the text itself and put it within a digital environment, developing from there a wide selection of resources to wrap around it. This has the advantage of allowing teachers to work with the texts they know and are accustomed to using. There may even be a visual representation of the actual text page on screen. This, therefore, can then accommodate additional resources, whether video footage of a historical event or an audio file of a section of Shakespeare being read out; teachers can zoom in on photos, hyperlink to glossaries or select the boxes with questions in them. There are additional benefits to such resources; of course the pupils should find the topic comes to life with video footage but it goes deeper towards issues of access: if, for instance, some children have problems with literacy, an audio file can be a great help.

Additional resources and activities for teachers to integrate into their teaching may also be available, and one of the exciting developments around these products is the flexibility that teachers have to pull apart a text and rebuild it for their own use in the classroom. An online learning environment allows teachers to select various resources and elements from different parts of the text and build them together into a new way of teaching a topic, setting everything up in the VLE to be ready to teach the course. User-friendliness of such products becomes key here as teachers do not have long to spend on lesson planning so simplicity is important when mixing and matching elements from a text to produce a customised lesson. Many products will use a similar environment across a range of subjects, tying together numbers of titles (even if the teachers teaching these topics may be from very different subject areas) and making the product buildable for a school.

Problems for publishers

However, various problems arise for publishers when developing these products. These revolve around:

- quantity (and cost) of material

o robustness of the technology

- flexibility and user-friendliness of the program

- school budget and the business model

Cost

One of the problems publishers face is that of selection versus cost effectiveness. Once material can be multimedia there is an endless opportunity to add more and more exciting aspects to the resources, but that can be costly. It can mean the development of thousands of resources; creating the resources from scratch is expensive, though in the longer term owning these resources can be of benefit to the publisher; otherwise getting permission, in itself a time-consuming process, can be expensive, and extent of the permission can be an issue too (if these products are sold into other territories, for instance, the permission needs to cover those territories).

At some point the authors and editors need to decide when to stop adding new material. By basing the products closely on the books or even on the page, this to some extent creates a natural boundary between what to include and what additional material to add in. Also the material needs to be really effective. It is easy to find free resources on the web, but by searching out and selecting key materials the publisher both saves the teacher time and ensures, hopefully, that the material selected is the most appropriate and effective for learning. This may ultimately add to the cost, as the best video footage of, for instance, an historical event, may cost more to include, but it does offer a selling point that can be attractive for teachers, who may not want to seek out permission or identify the most informative pieces themselves.

Technology

An important aspect of these products is their robustness. There is no room for technological glitches when working in a classroom environment. The online product also needs to be adaptable for a multitude of platforms and networks, which proliferate in schools, and support needs to be provided for whatever platform schools have adopted. Schools need to upgrade constantly and digital resources need to be flexible to keep up to date; clearly working within an online environment makes this easier, but some things are downloaded and/or used and customised locally to the school, so these need to be integrated effectively with whatever system is used. The products need to work quickly and easily so there is no delay in downloading materials nor any risk of the server crashing. Helpdesks to support customers are necessary.

Flexibility and user-friendliness

There is also the question of how far these really can be flexible. While they clearly are more so than a printed page, it can still be time consuming for a teacher to plan a lesson using them; they may not have the sort of flexibility to cope with different levels of learner as it is hoped; assessment built in the form of, for example, multiple choice or homework activities may be very limited and may still encourage a rather homogenous way of learning. Debates about how far digital learning has yet to go to cope with these aspects continue, as the pedagogy around the use of technology to improve learning has yet to be fully applied in a teacher’s day-to-day work.

The business model and school budget limitations

The underlying business model for publishers of these sorts of resources remains the same; adoptions of print texts bought in numbers for class sizes and used for a certain number of years form the basis for digital product sales. However, the pricing mechanism for multimedia products is more complex than a print adoption. These require a change in mind set around issues such as:

- licences and subscriptions

- duration of subscription

- decision-making around an add-on purchase to the textbooks

- what the school owns in the digital content

- renewal points and potential budget savings

- how a school judges value for money

Institutions need to examine new purchasing models. They may have to buy user or site licences, and a subscription model is often more applicable for an online product given the continuous access to the site (rather than the one-off purchase of a print text). This subscription element for web-based sites has represented a change for schools in terms of purchasing model; it commits them potentially to paying more further down the line in order to continue the subscription. Publishers have made this transition a little easier. Subscriptions cover different periods of time and often schools can access sites for the duration of the curriculum (or for the course of the life of the adoption of the print text) and it seems that schools have not had major problems with this new way of purchasing material. Prices are set according to the size of the school (number of pupils etc.) and teachers often view the support of good flexible resource material as beneficial as lessons can become much more dynamic immediately with access to the online resources available.

Certain problems are posed though. As we have seen, producing wonderful and effective teaching resources of this sort is not cheap, especially when the print text still forms the basis of the teaching and needs to be bought for students to use in the classroom and at home. Buying electronic products with all sorts of exciting additional multimedia elements presents a different budgetary proposition. A school cannot necessarily simply add to its budget and yet this is an additional purchase. A teacher may have bought a resource pack, usually at additional cost, but the price of these products is usually more and yet a school still needs the actual texts themselves, so these will come out of the budget first. Other costs may take precedence when schools consider their budgets: they need to bear in mind how long the books will last in terms of the curriculum changes due, and if the textbooks wear out, then titles need to be replaced, so that too will have priority; they also get economies of scales when purchasing bulk copies. So the budget that is left is not always that large and they need to ensure they get value for money.

Of course excellent resources encourage loyalty to a text and so it is important to ensure online sites are affordable as that may encourage sales of the textbooks. If the subscription is available for a fixed term, i.e. until the next syllabus, the price will often decline according to the length of time left to run; some publishers are working with this model, though it is not a firmly established pattern yet. Books were owned by the school, but to what extent do they own the resources that are available digitally? These will essentially disappear once the subscription has run out and the school does not have anything tangible (such as an archive).

This method of purchasing material needs to be considered in light of how far it represents value for money. It can therefore be seen as a much more discretionary purchase, one that will be easy to cut should cuts be necessary. The term of the subscription therefore becomes key for the publisher: it wants to ensure long enough access for the resource to become embedded in the customer’s daily activity so that it will be considered an essential purchase next time round, while also ensuring that there are not too many renewal points at which the school can decide not to renew.

Sales strategies for these products

Print textbooks are reasonably easy to sell in that customers know what they are getting. They read the marketing literature abo t them, attend fairs at their school to look over new titles, view inspection copies and quite quickly get an idea of how good the text is. Sales reps know a lot about the schools and the sort of curriculum they are working with, together with the range of pupils, and can direct the textbooks appropriately.

Selling these digital products becomes a little more involved. Demos are available online but it is usually more effective if customers can be shown these products much more closely. The more customers can get to use the products the easier it is for them to see all the benefits. Tying the resources to the textbooks helps of course but the interactivity and usefulness of the products need to be shown more directly, so sales strategies have to be tailored to this. Teachers do not have a lot of time and there are only certain times of year for decision-making in terms of book buying; finding the optimum time to sell in an ancillary product can be difficult. Overall this has led to a trend of building closer relationships with key accounts in order to sell products – something that may be set to develop further.

New product development

While cost is an issue, the creation of online learning environments like these involves a lot of additional development work for the publisher. New material may need to be created in a way that has not been the case for the journals or reference sectors we looked at earlier. While those sectors have focused on the manipulation of material once within the system (and added access to new materials), the actual creation of material has not been a factor for them. For schools publishing (and in Chapter 9 we will see consumer publishing) commissioning additional elements has been key, whether it be photos, interactive artwork, video footage or audio files. Not all of them are created from scratch – we have already touched on the fact that some things will have be bought to use with appropriate permissions but some will be created, commissioning voiceover material or filming parts of a play, for instance. So editors working on these projects need to act to some extent as producers as they commission a variety of resources.

These websites also need to be storyboarded in particular ways to ensure the right additional resources are commissioned. Creating user specifications, understanding the structure of the website and considering the way the product will work for the end user are all important when developing these products. The structure is also important in order to develop the metadata behind the various elements effectively so that those elements can be easily identified and linked together across the digital platform. This requires development of workflow and data warehouses, which are costly for publishers working within a marketplace that is price sensitive.

Higher education and e-learning

The development of digital resources for lecturers and students

For higher education similar market trends are in play as for schools but driven by the fact the end user is the student. We will look more closely on p. 101 at ebooks for both schools and HE markets, but texts in ebooks format, or enhanced ebooks format, have been available for some time and these have been predominantly rendered in a web-based environment as the books are too complex to be presented on simple e-readers. However, the main investment in digital products in this market up to now has been, as with schools publishing, in providing digital resources that support a print text.

Developments in digital products started, particularly in the US, by focusing on building web resource pages for lecturers to use to support the main adopted text.

In order to make their package attractive to professors so they would adopt their book, web resources were a good way to add value, doing something different and exciting. These included additional case studies, video banks, more activities, discussion points as well as multiple choice questions that could be given to students. In this way, sophisticated and enriched web resources have been developed, much like the schools market.

Expansion of these services has continued but there is an increasing focus on the student user, not just the lecturer. It had been easy to forget the student user (who actually has to buy the book), instead focusing on getting lecturers to adopt. However, as publishers look for new ways to add value they have started to use technology to increase student interaction with the text and build on the student package around the product, particularly in relation to e-learning.

The implications of e-learning for print texts

The HE market has been changing in its application of technology, which means publishers need to engage more closely with the way technology is used for learning in terms of structure and presentation of content. It is clear that the nature of the textbook even in digital format is still linear, and this clearly reflects the nature of the curriculum, which is in itself linear. Publishers are aware that the textbook is still very much at the centre of teaching for a course in whatever format, as it can follow the curriculum very closely. Education publishers in both schools and HE sectors therefore always ensure they keep close to the changes and development in the curriculum, and this relationship will continue to be important going forward. But it still generally starts with the print product: a text is written and developed with the course in mind and, as we have seen, the digital product can be developed in tandem; even with an iBook type of textbook, which we will consider in the case study on pp. 102–3, it is still tied to a linear process. It is the adoption of the print title that remains the pivot in the first place for the sale of the digital resource.

However, for many, something much more fundamental needs to happen to textbooks and there is an aspect of digital publishing that is focused on e-learning – where all the learning is done within a digital environment. This area is attracting more attention. For publishers it is an opportunity to embed themselves more closely into education, both at schools and HE levels, exploiting and customising content in a variety of ways, such as providing assessment or creating e-textbooks or collaborating on distance learning programmes.

The definition here is loose but it is important to draw some distinction between digital publishing and e-learning. E-learning tends to refer to the fact that the transfer of knowledge occurs within the electronic environment; it can cover such things as computer-based training (CBT), internet-based training (IBT) or web-based training (WBT) and it may involve some sort of controlled assessment to reflect the progress of the e-learner. This is not necessarily directly the realm of the publishers, though some are moving into these areas more than others.

In this arena the way an education product works often involves some elements of control of the learning process. The linear approach described above can be regarded as limiting. A much more flexible learning experience, that can still build towards a full curriculum in a more intuitive way for an individual user, is possible in a digital space. However, in learning environments it is not always appropriate for a user to be able to jump in anywhere. Just as the curriculum itself needs to be followed in terms of building blocks, one thing needs to be learnt and understood before moving onto the next stage, so e-learning needs to take some consideration of that. This does not necessarily apply to resources under the control of the teacher as in the products above, but there are situations where this does become an issue, in, for instance, effective assessment programmes. The relationship a learner has with the content of their course is beginning to change and this has implications for the print text.

Technological developments in e-learning

Developments in technology are important here. Learning management systems (LMS) are the systems used by organisations for a variety of activities from managing student records to running distance learning programmes. Different organisations will use their LMS for different sorts of things; they do not necessarily have to encompass much learning material, though institutions may have a learning content management system (which tends to be a subset of an LMS), where the actual content used for a course may be held and/or published for students.

There are some standards that have been developed to take this into account when developing learning management systems. SCORM (Sharable Content Object Reference Model), which emerged from Advanced Digital Learning Initiative, is a system that has been used to sequence material; it creates relationships between content that mean that the order in which the content is used is defined, creating a pathway for the learner; this can be particularly important where testing may take place, for instances in a self-learning environment, so the tests can be reasonably expected to test what the user has learnt so far. There are other uses and the critical aspect is that SCORM content can be delivered on any SCORM-compliant learning management system – so creating a level of compatibility across learning objects.

These technological developments are important for the development of more sophisticated products that tackle e-learning. Educational software producers create a lot of products of this sort but publishers are engaging with e-learning more and more as they develop and publish online assessment systems or more sophisticated online packages that can be integrated into a college LMS, for instance. For some publishers this is a particular area of focus as they protect themselves against declining print sales; for others it is a key part of a globalisation strategy where they can bring their material to new online learning markets around the world. The challenges of e-learning clearly affect both the schools and higher education market, but it is the latter where there is currently more activity. US publishers in particular are developing new approaches; this brings us back to the size and competitiveness of the market, which can engender high levels of investment.

Developments in e-learning and e-textbook products

Some publishers have created hubs around particular areas such as marketing where students access the specific textbook they are to use together with additional materials and additional tools to help them plan and organise their work (e.g. MyLab, Pearson), and which can also include access to their assignments and grades. These often have some sort of communications element so students can chat to their classmates about topics, email instructors, get involved in discussion forums, and can also include links to apps of enhanced e-textbooks where bookmarks, highlights and comments can be shared within the book. These sorts of hubs are highly customisable to the course and linked to a menu of textbooks which can be accessed if part of their course.

Overall this sort of development needs to manage the central issue in the area of higher education: students need to be satisfied as well as lecturers – by being able to customise resources around either the lecturer or the student the text becomes more flexible and hopefully attractive to both sides of market. If the student is pleased with it the lecturer is more inclined to adopt it. The student is, therefore, becoming more involved in the process of developing the textbook than previously was the case. In this way, even if the lecturer does not use all the chapters in the book the package can still have value, encouraging students to extend their learning too, and the more that can be shown to the student about how effectively they are learning, the more value they will feel they get from the package. This might then have the additional benefit of more students wanting to purchase the text, feeling like they are getting a complete service for their purchase, something they could not get with a second-hand print copy.

Lecturers can also benefit from the focus on tools to manage the course (and not just the text). Lecturers want to be in touch with their students’ learning, and if the text can be integrated more seamlessly into the other aspects of their learning on the course that can be of benefit to the lecturer; if they can monitor the progress the students are making, both parties can be more closely engaged in the student’s learning. If the lecturer and the student work can also be integrated together around the core product, the student might feel more obliged to sign up for the product, while the lecturer would see all the benefits an integrated platform might have for the organisation of their course, drawing the lecturer and student closer together in the decision to adopt a text.

Publishers’ new ventures and the new players

Publishers in the US such as McGraw Hill have also developed centralised tools providing web-based assignments and assessment platforms that can be linked to particular texts (e.g. Connect). These systems are aiming to take the development of digital learning further, moving beyond simple multiple choice assessment to much more integrated and sophisticated practice exercises. These are intended to work alongside whichever book the lecturer chooses, yet still have an automated marking function, providing a certain level of feedback and suited to the individual student needs – in that they can access this whenever they want. For introductory university and college courses, which have huge numbers of students, lecturers can manage these large numbers effectively. Also, because of the large numbers involved, these tools, which add so much value for a busy lecturer, can potentially command more revenue, which allows the systems to be built to a sophisticated level. Customising these effectively (with technical support at hand to help you do this) is also part of the package, as well as the ability to build it into any VLE or LMS system the college or university uses.

From this one can see how the trend of building distance learning around the texts linked to specific courses can easily grow. Here publishers are really trying to tap into the resources of the university rather than those of the student in terms of the end purchaser. Selling a product at institutional level makes a lot of sense compared to selling lots of textbooks to lots of students. For sophisticated products in any case the publisher needs to make a large-scale investment, so it has to sell to an institution to support the costs. Reps are already meeting the right people in an institution and so the sales strategy is to get more direct value from the institution rather than have to sell the product again to the student once the adoption has been made.

This all means that the textbooks become much more integrated into the workflow of the course for both the lecturer and students. The more embedded they become, the more involved the process of moving on to a new text becomes when lecturers want a change. Continuous innovation in these areas becomes a vital part of a publisher’s ability to maintain an adoption. It also becomes a way for it to gain a competitive edge and gain a new adoption by making customisation easy and encouraging lecturers to move to a new platform, which creates new opportunities for publishers to provide something unique where the texts themselves have become more standardised.

For these things to happen critical mass becomes even more important. Consolidation around key players in the US particularly has been an important step for publishers to be able to develop comprehensive content that can then be customised into course materials.

Once publishers develop frameworks such as these it becomes even easier to customise products to a course as well as develop new content to fit. By developing content in particular ways, it can then be mixed and matched differently according to the way it is to be used. As in the professional markets outlined above, new markets can be reached more easily, with the same basic content, if it can be adapted and customised according to different market groups or segments.

And so the dilemma around price becomes even more critical. For publishers there is upward pressure on prices given the cost of developing increasingly valuable resources based on the core product. But this pressure on price has spurred others to rise to the challenge of offering more cost-effective products. Companies entering the market are aiming to bring prices down or, if a course so chooses, make material free.

Inevitably there are other organisations moving into the market. We will explore the significance of the developments by Apple with their iBooks product for both schools and HE markets in the case study on pp. 102–3. However, developed by Apple specifically for the HE market, iTunes U is an app that allows lecturers to create and design courses easily (without necessarily being tied to a textbook of any sort); a lecturer can give students access to all the materials for their course in one place – so they have a bookshelf of items linking their iBookstore and their iCloud in one place, as well as links to websites, videos and presentations (maybe of the lecturer themselves), and assignments, keeping notes, highlights and documents in one place. These can be synced across all their Apple devices (so ensuring continued purchase of Apple hardware). Tools make it easy for a lecturer to build a course around all these elements. This is similar to the sorts of integrated platforms described above, but the step that Apple takes with it is the ability to publish that course globally – so anyone anywhere can access it – and in addition, if you choose, it can be available for free, fuelling the debate around the democracy of education. It may not be the whole course that is available but it could be a particular presentation, and many well-known institutions are using this to develop free materials for anyone to use anywhere on almost any subject. These in turn, where they are copyright free (or perhaps using a Creative Commons licence), can be built into more new courses where lecturers feel they are relevant. This is taking the learning ‘anywhere anytime’ issue of ubiquity to a new level.

The development of the e-textbook for schools and the HE market

These digital developments, as one can see, extend learning to new levels and involve a considerable investment and consultation. However, the print text still remains in place. But for how long? The next stage of development is likely to focus on ebooks and the individual use of digital textbooks for both the schools and HE markets, and new players are coming in to attempt to shake up the market.

Ebooks and e-readers

In most cases textbooks, at whatever level, that are produced in print are also usually available as ebooks. Up to now standard ebook formats are not the best way to render highly illustrated, very integrated textual layouts. Even for more text-based materials

(i.e. without the extensive full-colour illustrations and photos) EPUB formats simply cannot cope with the complexity of a standard textbook at any level; while some work can be done to the files, the main problem is that the school texts are designed into complex page templates, while an EPUB file is not really designed to manage page formatting at all. In addition, EPUB files may be reasonably standardised but they can still render differently within different hardware, so they have to be checked across all possible options. E-readers have not been seen to be of much use for the textbook market.

Many pupils will have their own laptops, particularly at secondary level, and at HE level they generally all will, so they can access ebooks. For schools though, to ensure access for everyone investment in hardware will still be required, and so selling ebooks has not been a focus for this market.

For the HE market the purchase of ebooks is much more prevalent. Sites such as CourseSmart, set up by a group of the largest textbook publishers in the US, provide a one-stop shop for purchasing e-textbooks, making it easy to read in any format, anywhere, with attractive discounts on the books for students. There is also a growing rental market for ebooks, with, for instance, Amazon in the US offering this option on its site (as with its print textbook rental market); this can prove an attractive alternative for students and one that is easy to manage in a digital environment. This could well have a significant impact in the longer term.

Future developments for educational publishers

Building up the assets: digital warehouses

Whether building an online resource or developing a textbook such as the ones available in iBookstore, there is a clear overall trend towards interactive resources and more highly developed visual material and photography. Taking images alone, these could represent quite a lot of the cost of print books. While there may still be a cost to developing the images, the actual reproduction of them within the digital environment is not expensive in comparison to the high-quality printing necessary for physical books. There will still be costs, whether to buy the rights to the photos (these will often need to cover global rights, depending on the sort of DRM/access controls the materials have and their ability to cope with territoriality) or to commission artwork, photos, diagrams, maps, cartoons and other illustrations. There could well be an expectation in the market for a digital product to contain more of these sorts of elements, so there is an incentive to ensure as many as possible of these features are included in the product, so that the market feels justified in purchasing them.

Case study: The development of tablets and Apple’s iBook textbook

The growth of the tablet market has entirely changed the potential for the use of digital books within the classroom and could well revolutionise the learning environment at all levels. Tablets can reproduce the high-quality full-colour graphic nature of the textbook while being much less cumbersome to use than a laptop. They offer the opportunity to bring e-textbooks to students to use in lessons, easily and quickly; long battery power and robustness of the systems are also advantages. There are obviously issues about providing tablets to pupils given the expense of providing and supporting so much hardware (not least entrusting pupils with pricey technology compared with reasonably cheap print texts). However, while it is early days, there are examples of UK schools using iPads in class and in the US whole school districts are supporting the adoption of iPads in their schools. The attractiveness of iPads for the HE market is also of critical importance.

The development of the tablet for education use has very recently been accelerated by the introduction of the iBook textbook by Apple for use on its iPad. Apple has identified the education market as one where it can promote hardware sales with the introduction of tools and platforms on which textbooks can sit. These are books (rather than apps), which may be media rich but still follow the format of a basic book.

More critically, Apple has created user-friendly development tools that it makes available for free in iPad Author, in order to encourage people to make textbooks that can only be used in iPad environments. This authoring tool is very easy to use, providing creators with templates to help them upload photo galleries, use html widgets to enhance user interactivity with diagrams, include presentations, manipulate 3D images, insert video or audio files and create tests, while the book itself will provide additional user-friendly tools such as the ability to make index cards for learning from highlighted text.

The impact here is likely to be greater in the US than the UK. One of the aims is that, with more content available, customers are attracted to the hardware, and schools and college markets will feel they need to embrace iPad technology to offer their students the best products. The pricing is a critical factor here. While the prices within the iBooks textbook store are comparable to UK-based texts, they are considerably lower than US prices, which is one of the issues in debate.

The other critical issue for the US is that the opportunity for individuals to develop texts themselves may prove a big problem for publishers used to operating within the system where textbooks are adopted centrally. It is much easier for teachers to develop their own materials, which may start to dilute the big adoptions and allow access to materials that, while they may not be the best, are of reasonable quality, look good due to the flexibility of the Apple software and are considerably cheaper.

Publishers and the iPad in education

Apple is not yet creating its own content and indeed may never intend to do that. Its aim is to encourage people, including publishers, to use its authoring tool to create content and post it onto the store (incidentally driving Mac sales too as Macs have to be used for the Author tool). So Apple launched its textbooks iBookstore with books produced by the key US textbook publishers (McGraw Hill and Pearson) to show that it is not alienating publishers but, instead, is keen to get them to use Apple’s tool in order to produce high-quality content. Nevertheless Apple also envisages the tool being used by individuals, such as teachers, wanting to develop their own texts and creating highly individualised teaching materials. While Apple does take a percentage of any actual sales of a book on the iBookstore, an individual teacher’s textbook can be posted up free on the iBookstore (with Apple therefore encouraging true internet democracy to self-publish and freely share), which means that competition will therefore be increased, or, at the least, the market diluted.

The problem is that the proprietary nature of the hardware means that publishers face a dilemma when developing products. Publishers have to make decisions as to the format in which they publish. Do they make all their materials available across all platforms and hardware? This will be something we look at again in the consumer market (Chapter 9), but in the case of the iPad, if publishers use iPad Author to produce their texts, they can only be used by schools or individuals with iPads. Even if iPads are very widely adopted, not everyone will adopt them, and are they then excluded? (This is a debate which is all the more pointed when it is about education.) If they do publish for iPad specifically using iPad Author there are certain restrictions on the content that Apple have built in, which means publishers cannot necessarily use everything again exactly as it is in a different format for a different tablet – something that can be a problem if they are looking to produce consistent education materials. Publishers have to be aware of this issue and decide whether to develop their own system and make it available on Apple devices rather than use Apple’s own tools. There are some issues around how far a publisher can reuse some of the materials provided within the iTextbook too, which can cause problems.

The advantage of producing digital texts for publishers in places like iBookstore is that they are able to reach a larger market. They can attract global audiences in a way schools publishing hasn’t been able to do before. Curriculum-specific texts are unlikely to travel much beyond the remit of the exam board (which may be wider than just the UK but is not generally global), but for some titles, such as language courses or literature texts like Shakespeare, they can tap easily into markets that were prohibitively expensive to reach before.

Even in the tablet environment, however, the books currently developed are still textbooks that follow a clear narrative structure and work from page to page as a normal book would. An iBook allows for the use of beautiful high-definition resources but it is not a hugely innovative or interactive experience compared with the e-learning environments described earlier. And once set they cannot be pulled apart and adapted and customised any further. There are some dilemmas about publishing materials like these. They are not necessarily much more flexible in helping students to progress at different rates than standard print books. They are still bound to the curriculum and new books are needed every time the curriculum changes.

Publishers therefore have been developing data wareh uses and digital asset management systems, as outlined in Part I, where they can store and reuse material effectively again and again. This means they can easily reuse information at the point a syllabus changes; while artwork could previously be redundant or fiddly to repurpose, storing materials in a digital environment means they can not only be reached quickly but reused and adapted quickly and cheaply; given that key concepts, say in geography, will remain the same even when the syllabus changes and the fact that the old texts based on old syllabi are no longer in circulation, the reuse of material makes sense (and is not just cannibalisation of a publisher’s material).

However, three key issues are important when developing this sort of system:

- copyright

- standardisation

- structure of the data warehouse

The publisher has to own the copyright in the artwork; in many cases, publishers have been accustomed to commissioning images and owning copyright in them, so this fits well with them.

The material needs to be in a standardised format. Metadata will sit behind the material, whether text or visual, but, with artwork especially, there needs to be stan-dardisation in the creation of the material in order for it to be easy to use again across a variety of different texts. There are problems with this. The design of texts needs to be rationalised so that standard templates are easy to create using a few set styles, otherwise everything becomes costly again if it needs to be customised in some way or other. There will clearly be flexibility around the styles, but they may be limited to a smaller set of style sheets for the sake of cost effectiveness and to ensure content can be created so that it can be used across a range of products. This is unlike the print environment, where different individual designs per book (or book series) would be common and there is a risk of homogeneity. Publishers involved in this development tend to have an aim in mind for the percentage of material that will be reused compared to newly commissioned material, in order to ensure the overall effect is still unique.

The structure of the digital asset warehouse needs to be developed in such a way as to ensure effective use. Once again, this means the application of metadata in order to identify images that may be suitable for a particular project; recording the ongoing use of the images is also important, so that images are not overused and the look of books, while standardised, is not too homogenous.

However, digitisation of their production methods can allow publishers to produce materials cost effectively, which can help towards the development of expensive digital resources for the market.

The role of the author and the standardised text

What does this mean for the author? As the development of resources becomes more standardised, can, or indeed should, the work of the author become standardised too? Will written sections be chunked in a similar way and pieced together in different formats for different occasions? Authors within the education sector have often collaborated to piece a book together around a curriculum. Some work on the whole project themselves and deliver a piece of work that is individual and very tightly constructed. However, some projects are built by a selection of writers who work on sections or different types of resources, mixing and matching skills and piecing sections together in order to work alongside a syllabus. These authors are already more used to working around parts of a book, knitting it together at the end, and this approach can work well within a digital environment. In order to support the costs of setting up, delivering and maintaining digital resources, the ability to rework content becomes critical as a way of managing content cost effectively. Of course, some may feel that this has the potential to undermine the quality of textbooks as they become more homogenised; careful editorial work can ensure this does not happen, but the drive by schools to achieve exam success does mean the market has an interest in producing books that can achieve this for teachers, which does, to some extent lead to a perceived ‘standardised’ textbook. This debate has become all the more furious in the higher education market.

There are a variety of issues that will challenge educational publishers in the future, though some may provide opportunities. Digital warehouses are key to the future developments but there are other important areas that need to be taken into account. These include:

- budgets

- accessibility (especially in relation to technology)

- curriculum change

- customisation

- new business activities, e.g. assessment and the development of communities

Budgets

Budgets will continue to be a problem for markets essentially funded by the public sector. School budgets will always be tight, and in periods of recession even more so. For schools, as new digital products are produced, their cost is not necessarily likely to be low. If they are discretionary purchases, there will be pressure to prove their worth; if an e-textbook becomes more central to a course, the costs of supporting the hardware can be a problem, and if schools have to do that it may be with the expectation that the actual materials will be cheaper. This puts pressure on the print texts around which some of these digital products have been built. The trend towards working more closely with the institutions, arguably more advanced in the US HE market, may therefore become more important.

Accessibility

Among the issues that will continue to be important, there will almost certainly be a focus on accessibility. Clearly there is an issue with access to the technology itself. Technology is expensive and can need continuous servicing: the more education products become dependent on technology, the more accessibility may be threatened.

There will need to be ways, for instance, to support poorer students who cannot afford an iPad, or schools with low budgets that cannot support the computer services they need.

There are also purely technological problems around access. For instance, materials created using Flash may become a problem as Adobe will not be supporting this in a few years’ time. This may mean the re-rendering of materials that used Flash. HTML5 will offer the sort of flexibility to embed multimedia within websites, which may also be future proof as it is a generic standard, but what it shows is that publishers in the education market need to pay continuous attention to the way they create their resources, to ensure they continue to be accessible despite changes in software and hardware, and keep track of where the education market is spending its technology budgets. They cannot second-guess every technological development but will need to be ready to change and upgrade materials where they can quickly. Ensuring the raw format of the material is as flexible as possible is of course a critical aspect of this, but they will also need to review which systems and programs they can and cannot publish for, and allow for additional cost to keep their materials available throughout any technological changes.

Curriculum

Of course the driver of education publishing remains the curriculum. Remaining flexible so as to produce high-quality content quickly at the point of curriculum change is critical to a publisher’s commercial success. Print products take time to produce, whereas the digital environment can sometimes allow publishers to reap the benefits of bringing materials to market quickly – as sections can go live as soon as they are ready. This, however, still requires considerable management, particularly when there are major changes in the curriculum across a wide range of subjects; being prepared to manage this will be crucial. Trends around e-learning will become more critical, as technology can deal more effectively with independent learning opportunities or different learning levels.

For both schools and HE levels there is the opportunity to customise products for specific needs and uses. Publishers can work closely with a school to pick and mix materials or services to link into the school’s VLE, or they can put together content from a variety of sources to produce an ebook according to the specifications of a lecturer (which already happens in print). Publishers will have a lot of exceptionally well-developed content that is of great value, so offering opportunities to schools and colleges to individualise learning for their own students with bespoke packages will be a way to realise value across their content. Also, most teachers will accept that while they can do some limited self-publishing within iPad Author, they cannot necessarily match the depth, range and high production quality of content produced by a publisher.

New ventures

As we have seen, some publishers are experimenting with new ventures and developing more expertise in areas wider than traditional publishing. Taking Pearson as an example, as mentioned above the company has been building expertise in assessment, buying the exam board Edexcel in order to turn it from a charitable organization (as many exam boards are) into a commercial enterprise. There are problems with this model, not least around the monopoly position Pearson has in relation to publishing textbooks for the courses, and there are pressures on the way this can be effectively managed and organised, but in Pearson’s case the link between learning and assessment is important. It is something which drives its strategy in other parts of its business, for instance in language assessment in Asia or professional clinical assessment in the US. This links Pearson to the arena of educational software and knowledge management systems so it builds expertise in areas around the management of education as well. In this way it can become much more embedded in the educational market, supporting a range of technologies within schools, colleges, universities and the professional training sectors. Other publishers are developing different sorts of collaborations that are more integrated into the education sector, around, for instance, e-learning; and on a smaller localised scale it can be seen that publishers are getting involved in helping schools create and support their learning environment. This provides some exciting opportunities but is of course a huge challenge. Like the professional reference sector some of these publishers are in the process of changing the sort of company they are.

Learning communities

There are also developments around creating communities, using content and support materials in a new flexible way based on a customer-centred approach. The community can centre around a topic or subject and get access to support and material at its point of need. For instance, communities for English language teachers have been developed where teachers can ask others for advice, access key authors in webinars, find articles by professionals or source materials on related topics, with self-assessment sections for their own personal development. The benefit to the user is that they can interact with fellow professionals who they may not necessarily be able to meet in any other way, and get answers to much more specific and individual questions. For publishers, it means they have a two-way conversation with their customers and can understand more closely what they want and help to develop it for them. These systems can work on a variety of levels – they can be entirely free sites in order to develop customer groups and build loyalty, for marketing around specific titles, or can become a little more of a standalone service in itself that users may access for different prices (e.g. freemium models, where certain parts are free but others can be paid for on subscription or by use).

So education publishing faces particular challenges in the future. The market is embracing technology but cost is a problem and price can be a barrier. They too, like the academic market, face the criticism that education should be freely available and encounter resistance to increasing prices. New entrants to the market are driving the move away from print books and changing the cost base of the sector. Publishers have to reinvent their role, drawing even closer to the sector and changing the way they work with their customers. Yet some argue that the digital products are still quite limited in their scope and the full extent of what digital technology can provide is not yet being fully exploited. Here both the sector and the publishers will need to move together to create the digital products of the future.

Books

Clark, Giles and Phillips, Angus. Inside Book Publishing. Routledge, 2008. Thompson, John. Books in the Digital Age. Polity Press, 2005.

Websites

oyc.yale.edu – an example of a university posting up free lecture content; limited in scope but nevertheless providing free resources for blended learning opportunities

pearsonmylabandmastering.com/learn-about an example of a student digital hub for their textbooks and learning

wikieducator.org – an example of a wiki site aiming to aggregate free e-learning content for open use

www.apple.com/education/ibooks-textbooks – Apple presentation on their iBooks textbook for iPad.

www.bettshow.com – for the BETT educational technology show

www.education.gov.uk/aboutdfe/armslengthbodies/a00192537/becta – archive site for BECTA and Harnessing Technology Grants

www.education.gov.uk/schools/teachingandlearning/curriculum – government resource for information about education and the national curriculum in the UK