Developments in digital professional reference publishing

In this chapter we will cover:

- Reference and the benefits digital opportunities can bring

- Early digital developments in professional reference

- Issues around migration of customers into a digital environment

- The changing relationship with customers and how this has influenced the growth of digital products

- Ongoing product development

- Pricing and sales models

- Future developments

There are many sectors of professional reference publishing, from medical and technical material to legal and financial content. This chapter will focus on the development of legal professional reference publishing but the other areas can be seen to operate in similar ways.

One of the first and prime uses of the internet is for finding information. The ability to search across an array of online material, tap into a variety of sources, follow links to further information and ultimately pinpoint exactly what is required has been one of the central features of the rise of the internet since its inception, with the additional benefit that much of it was and is available for free. The use of the internet for reference information therefore has challenged publishers of material which was costly and time consuming to collect, organise and distribute via print. Not only can users seek answers across large databases of information at the touch of a button but users are also involved, since the rise of Web 2.0, in the creation and maintenance of more and more reference material, such as on sites like Wikipedia.

General reference publishers have found it a struggle to maintain their expensive reference information even in database form, as information can readily be accessed for free; this free information may not be especially high quality but it is reasonable enough for the general user. Publishers of dictionaries and encyclopaedias, like Britannica, targeted at the general consumer have found it difficult to maintain anything like their previous market share. There are still markets for dictionaries and encyclopaedias, particularly those with strong brand names and a long heritage of providing high-quality information created and endorsed by experts. Nevertheless a significant part of their print market has migrated to use free online sources. These businesses have had to find models to help them survive; for example, they may decide to target more niche specialist markets or license information or simply manage around tighter margins. These consumer market titles will continue to face the challenge of offering something different from the free sources available via the internet.

However, in this chapter we are focusing on reference within the professional arena as an example of the way more specialised reference material has developed complex and now well-established digital business models. Prior to the growth of the internet, reference information was mostly available within published print sources: this might be freely distributed (such as government information) or, for something more specific, bought by individuals, libraries or companies. What characterises this sort of reference material is that it is used by specialists. This chapter will be focusing on the developments in legal information as an example of professional reference: in this area publishers are finding rapid migration to online information and in some notable cases have pared their print down to only a few high-profile titles while concentrating their efforts on developing online platforms. This sort of development can be seen in other areas of specialist professional reference material, in the provision of news services and in business to business publishing.

The move online is of particular importance as the logic around what reference material is means that the online environment provides a much more effective space for it; easy, fast searching through large silos of material, together with unlimited storage and ease of access are obvious benefits. In this sector more than some, therefore, print has been viewed as having a limited life cycle. Meanwhile the relationship between the publisher and user of content has become even more embedded and this relationship with the customer is driving the future opportunities within this sector.

The benefits of digital publishing for reference

It was clear very early on in the development of digital publishing that the digital environment offered many unique features that could improve the use and consistency in quality of the specialist material needed for markets such as the legal market.

The key aspects of digital products that are of major benefit to customers can be summarised as follows:

- searching across large quantities of information

- searching more deeply across information

- up to date/real time

- availability of additional material – grey paper, raw law

- automatically updated

- ability to access from desktop – not just in a library

- capability for several users to access the same material at the same time

- cross-referencing with hypertext links

- links to other resources

- shelf space reduction

This list of benefits is similarly compelling for other sectors such as the academic sector. However, there are some additional benefits too: it is important across most sectors that material is up to date, but in the professional reference arena the material itself can be in a constant state of updating. The digital environment makes this easy and it is a particularly attractive feature of the digital product for specialists.

Early developments in specialist reference

The reason professional reference publishing was one of the earliest sectors to move into a digital environment is due to several factors intrinsic to the nature of the material itself. Even before electronic publishing became so prevalent, large quantities of reference material were held in databases that had particular value for certain customer groups and from which various products could be produced. Electronic environments made immediate sense as a way to store information effectively, extract it in different combinations and add to it continuously. In some cases this information was captured and stored in some sort of digital format very early on, even though the output to the customer was only in print form.

These sectors developed expertise in managing data files of reference material and the legal publishing industry began consolidating around the core competence of managing large databases of legal information in the late 1980s and early 1990s. This was not yet focused on the user of the information so much as a way of collecting, managing and storing information in an early content management system.

There are several aspects that are central to the use of professional information that helped to drive the products online and which we will explore.

Continuous integration and organisation of updates

Particular updating needs helped to drive the development of digital systems. In the area of legal publishing there are certain products that focus on the fast and efficient updating of legislation as new regulations and statutory changes take place. The digital environment was an ideal way to start continuously updating material as soon as government information became available. Indeed, core legal material is available for free, since it is produced by the government for the public domain, so arguably a user does not have to buy it. But what the publisher adds is a quick and accurate way of organising the raw legal information that comes from government so it can be readily used by the legal profession in various targeted ways. It is easier to integrate updates regularly into products within a digital rather than a print environment, and doing this quickly and efficiently is a key selling point.

Search

Added to that, the nature of reference material is such that the ability to search quickly and effectively for the particular piece of information required is central to its use and application. Organising material effectively and ensuring it is user-friendly is one of the aspects of publishing reference works on which publishers have always spent much effort. So the ability to find information in a vast database of material is improved instantly if the search can be carried out electronically. The move to an electronic format for the delivery of content to the customer was critical as early as possible as a way of maintaining a competitive edge over other publishers.

Automatic compilation of updates

Since governments continuously revise and adapt laws, many legal works were in the form of print looseleafs; an individual or, more often, an organisation purchases a subscription and then receives at regular intervals updates which have to be filed in the looseleaf, while the out-of-date sections are extracted. This is a fiddly and time-consuming process for both the compiler and librarian/filer. While a looseleaf is, more often than not, a product of legal and financial publishing, the issue of keeping a product as up to date as possible in an area that might be moving quite fast is an important one. An online database that is up to date as far as possible in real time clearly saves time, effort and cost.

Timeliness

When updates are due it is important that they are enacted immediately, yet with the print service (as updates were called) being issued at intervals there could well be periods of time when the product was out of date with current law. This too could be overcome via the online environment.

The early electronic products: CD-ROMs

Some companies started to use databases for the production of print products but many products were still being developed in a traditional way from manuscript to typescript files. Given the compelling reasons above, however, publishers were looking for ways to deliver an electronic product to the customer. As with other specialist reference publishers, the early forays into electronic publishing were in the form of providing CDs that were developed from the production files and which supported the print product. These CDs of course were still not updateable within a real-time specification: CDs were only issued as frequently as the print products. However, they did have four key benefits for users:

- They improved the search for the user. Being able to type in one keyword to search across a product, and in some cases a range of products, was a benefit.

- The actual updating was at least done for you rather than having to update print by hand yourself.

- Access was made available to a wider number of users depending on the number of licences a library bought. The idea behind this was that the work could be used by several people at once and for key works, instead of buying lots of print versions (and updating them all by hand filing), libraries could have one main print work and several site licences to the CD. The print costs could be reduced for publishers (essentially to fund CD development).

- As an adjunct to this, libraries could manage their shelf space more effectively and supply their legal information direct to the lawyer’s desktop. This was mainly managed for the market-leading titles. The move to a digital environment in this case matched demand for libraries to move online.

There were production limitations to the success of the early CDs. The main issues were:

- CD production packages: they were often cumbersome to use and, in the early days, may have used off-the-shelf electronic publishing packages that were not especially sophisticated, leading to a poor search experience. These conversion packages scanned in text and overlaid search criteria, but these were ultimately rather too simple for specialist usage. New CD-ROMs often had to be issued with the updated sections integrated, and that process was complicated and could lead to errors.

- Limited space: there were also problems with the size of the CD, which only has space to hold a certain amount of data.

- Changing systems: the developments in XML, coding and metadata provided a more sophisticated route to converting print material into digital products. However, early on companies often found that they had invested in one particular type of system for digitising and then had to move away from it and use a different system.

- Access controls: CDs could also be cumbersome to load onto a library system, often with complex access control and frustrating DRM to limit the number of users. Particularly frustrating was the DRM that shut the CD down once the subscription period was over.

- Existing comfort with print searching: customers who were used to print could find their way around it quickly by hand, flicking through the table of contents, or leaping to well-thumbed sections. CD-ROMs meant that users had to spend time learning to use the new environment.

- Cumbersome CD searching: the CD search could be unwieldy and pull up a lot of unwanted references. It might not be especially clear which part of the work you had ended up in. An early criticism was that although the customer knew a particular reference was within the work, the actual keyword search did not bring it up, maybe due to data error or the complexity of search protocol around paragraph numbering. This meant that unless a search on key terms or case references, for instance, was very specific it did not work effectively.

- Not very up to date: another early problem was the fact that the works were not as up to date as they were expected to be. A CD, for instance, was only up to date for a short time, essentially a similar time to the print service.

- Costs: customers felt the CD prices were not transparent enough and were too complex.

- Inaccurate coding: where databases were being used (rather than off-the-shelf packages) this could be a problem; something could get lost in the database and fixing this was time consuming and costly. The cost of the initial infrastructure was high; taxonomies and protocols had to be developed quickly but still thoroughly. It took some years to iron out the system for the archive, and then change workflow in order to contribute to the archive. The development of real-time, up-to-date works therefore took some time to follow as well.

However, these CD-based products were built essentially around key print book titles; off-the-shelf packages or small specific databases. Alongside these, large legal databases from which material could be extracted were being developed. Big publishers such as West and LexisNexis were building expertise here and companies were being bought that could bring technological innovation in developing database platforms to existing print legal businesses. Thompson, for instance, which owned Sweet and Maxwell, bought West in 1996, developing its platform into Westlaw and building key content it already owned into it. Reed Elsevier bought LexisNexis in 1994 in a similar way. Both West and Lexis developed full-text searchable databases around particular areas of legal information such as legal cases in particular states in America (and in the case of Nexis, a service launched by Lexis, a news article database). This data proliferated. In the case of Westlaw the information it holds in its American-based datacentre is so large it has its own power plant as a back-up generator to ensure it can keep going in the event of a failure of the grid. The products that emerged as these databases grew will be explored on p. 52 but they mark the beginning of the transformation of the reference arena into a fully digital publishing business.

Once information was being regularly processed into the data warehouse, properly checked and corrected and coded, and the main archive was up and running, the continuous addition into the databases became easier to manage. At that point in the development of the digital product, the focus moved onto creating effective front ends to the databases. These select and extract whatever content is most relevant for the target market sector. In addition, publishers can allow for more customisation for individual accounts (if they are large enough) as well. So the development became much more focused around creating good, effective, branded front ends.

Once the major infrastructure had been set up and workflows developed the next area for product development was to build the author into the picture more directly. Content management systems based around file sharing platforms have been developed to provide a seamless environment for the collection and management of content, including review and editing, so that authors can be commissioned to write and post up their content, review and discuss their content in chat room-style environments with appointed experts; then the content can be copyedited, coded, checked, etc. and sent to an online publishing platform, where it is published, when ready, and so the site is continuously evolving for the user (in many ways following a journals publication programme). Products such as these are not always as seamless as they might sound, but they do ensure the timeliness of the material even for a non-journal product and a constant supply of new information is available to the subscriber.

Infrastructure requirements and organisational change

To manage reference databases of this sort various structural changes have to be made. These were not, in the early stages, around the product offering but around the building and maintenance of effective information architecture. These companies soon developed relationships with suppliers in countries such as India and China, where inputting and coding of data could be managed effectively and cheaply. In some cases a further layer of data management was established where employees more expert at particular aspects of law are necessary to check the legal data is input correctly and ensure the updates of the law are inserted in the right place. This differed from those editors managing the products for the market, but required some specialist legal knowledge in the effective development of the database itself.

As products developed, these companies quickly developed departments where project management techniques could be implemented quickly to ensure infrastructure projects could be built; they could be involved in managing anything from the development of a generic platform to hold information (which might well require the employment of outside suppliers) to the design and architecture of particular products; from the delivery of a product to the consumer to the user experience of the product itself. Technology departments grew with a variety of experts who had various skills in creating coding systems, taxonomies, protocols and standards, etc. for technical information, thus ensuring that the database was developing in a way that would ensure it could be used in all sorts of conditions, anything from output in print form to customised products for key customers.

With this, other departments became necessary, such as helpdesks for customers and for internal users of the database; there could be specialist units to manage particular services such as daily news bulletins, as well as trouble shooting units and departments supporting the internal IT services for hardware and software. And new systems were needed to manage, for example, the correction of errors, or the flow of information from one part of the organisation to another, or for quality assurance and functionality testing.

As technology projects developed at different speeds, so organisationally there was a change; certain expertise might well have to be brought in for a period of time, with growing relationships with specialist technology suppliers. As projects developed, however, there were certain times when more inputting was required, while at others more testing was necessary. Developing organisations that can expand and contract as technology projects are set up has necessarily been a significant change; for the launch of a major work additional people may be needed, while at a later stage only a few people are necessary to maintain the system. The ability to develop a largely flexible workforce may be becoming more critical to product development strategies.

So the focus within these publishing sectors was on the effective and efficient development of the database itself. The database becomes a very valuable asset as the content driver for the company. The quality of the database, the taxonomies it uses and the flexibility in the way it can be used are important for the competitive edge of a publisher; there is intellectual property invested in the taxonomy it may have developed as well as the database itself. Therefore there is extensive value in what it owns.

This makes it, as we will see, a very different proposition from the consumer market. The publisher has ownership of something it has developed; authors may well play a part but the publisher owns a database that can be used in a variety of ways going forward as it responds to market change and gives the market the content it needs in the format it needs it in. It is an important aspect of this sort of publishing that the brand name of the publishing company is well known. The brand of a consumer house may be of less relevance to the customer than the name of the author, but in this sector the customer is usually aware of the brand name of the database product they are using and it is an integral part of the publisher’s relationship with its customer.

Migration issues as digital products are developed

The drive for migration from print to digital

When digital products were first developed in a major way for the market, publishers needed to explore how far these different groups of customers were moving online in order to assess the balance between the need for the print product and the need for the digital product. Printing and distribution costs in this sector of the market are high, as are the costs of database development; keeping both formats available is expensive, so it is an important factor to consider when publishers are devising publishing strategies. Some of the key questions still remain around whether it will be necessary to keep the print product, and, if so, for how long. Some publishing companies have moved away from the print market altogether: Butterworths sold a large amount of their print product (to a management buyout originally and now under Bloomsbury Professional), while other companies have seen a significant reduction in print sales.

As new products developed, publishers in the legal area regularly tried to research the market in order to assess how fast customers were moving online. This could be done by directly talking to customers about their needs and their migration strategies, and also by observing the behaviour of customers they could not research as they watched their buying patterns.

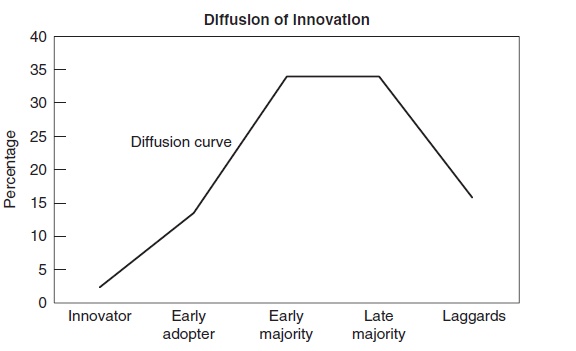

Figure 6.1 presents a version of the standard theory of diffusion of innovation, as originally espoused by Rogers1 in 1962, to illustrate the stages of adoption of a new technology. In many ways companies can be seen to fall into the categories illustrated according to how quickly they move into using digital platforms regularly for their reference content as well as how far they have left print behind altogether.

In the early years of the adoption of online products customers were often loath to relinquish a print version of the product. For some users the ability to search quickly in a physical product they knew well made them reluctant to take up the online product. But the capability for users to access the product from their desktop without a trip to the library and the capacity for several of them to access it at once were clear benefits. So, in the early stages, libraries tended to reduce the quantity of print products they bought, buying instead a licence covering a number of online users. Very few, however, would relinquish print altogether.

Early sales activity

At first publishers often developed the product and pushed it to everyone who had the product already in print, being rather ambitious about sales targets and predicting a much more rapid demise in the purchase of the print product. However, publishers began to look a little more deeply in terms of diffusion in order to assess the speed of change. Market research projects could sometimes profile customer groups according to whether they were likely to be early adopters or follow on behind; by scaling the sort of customer profiles across their customer base, they could identify those that it made more sense to tackle first with deals via their key accounts development, so ensuring they could maximise their sales effort effectively. As they analysed patterns they also saw that their expectations of complete migration from the earliest possible stage were misjudged; this had an effect on pricing issues. Similarly, the continued use of print mixed in with the online product was also not immediately recognised, again affecting pricing. These issues were not always due to the slowness of the customer to take up the online products: as we have seen, the quality of the product was also a factor.

Price and migration

One of the reasons why understanding migration patterns becomes important is that the pricing of the print and online product need to remain, in some way, in line, but the unit cost of producing the print product increases as the number printed decreases; this cost needs to be supported by the growth in online sales. The online sale initially for many products was developed as an add-on to the print product (where it was a direct version of a print product), though with the expectation that this relationship might swap later and the print product change to become the add-on to the online service; in this circumstance the idea was that the print product would become something a publisher charged a premium amount for. This situation has not yet quite materialised. The pressure has been to keep the prices of the print product reasonably in line with the existing and well-established price ranges for print despite the decrease in quantities; though the decline has perhaps been less rapid than some might have predicted for certain types of product.

Some of the online products did not have this problem, having been developed essentially as a new way to access legal information that was as real time and up to date as possible; the large legal databases such as Westlaw or LexisNexis fell into this category. Here there was no particular print legacy to accommodate. The migration of customers to an online environment nevertheless still posed problems in that the cost of developing these large databases needed to be supported by the consistent and strong revenues coming from the print products. Ideally, libraries needed to buy into new legal databases of this sort, which were essential to their business, on top of their existing spend. In practice, of course, while some initial additional budget would often be available to buy into the technologies necessary, some other area of the budget would need to be reduced in order for money to be directed to the new product.

Encouraging migration

There are ways to encourage or force the process of migration. For instance:

- Forced migration: forcing migration in some cases made the transfer from print to online more possible, though publishers risked alienating customers who did not want to move. For smaller products which might be in decline anyway, forcing the migration, maybe by providing CD-ROMs to start with and later online access, did at least give those products a chance to survive; savings could be made in the longer term by stopping the print versions. In other cases, migration was forced in order to be able to charge a higher price, a price necessary to support the cost of the online product. Models such as these were not always popular but were another early way to move the more reluctant customers online.

- Educational pricing: migration was also supported by a policy of special pricing for educational institutions which ensured the products were widely available in universities and colleges. As new members of the profession enter, having used online products in their courses they would inevitably expect them to be available in their companies.

Other influencing factors

One of the critical migration issues for the legal market was the range of customers using the products. It was often assumed that customers would want to move to the online product given the USPs and that the print could be cut out of the equation very quickly. However, there was a large number of users who preferred to use the print that they knew very well as they found that navigation was much quicker and easier than learning a new protocol through the online version. Older members of the legal profession did not want to have to change. That continues but the make-up of the user base will alter as students enter the profession and are not accustomed to using print. This illustrates how carefully the industry needs to observe the behaviour and work patterns of the profession in order to manage their publishing mix.

Changing relationships with customers in the specialist sector

Key customers

Publishers of information for professional groups of customers have always had a close relationship with the various segments of their market and are in direct contact with their customers in different ways on a regular basis, so they are very knowledgeable about their customers’ needs. Their key customers, often early adopters, are particularly important in the development of digital services. Large corporate or institutional buyers spend significant sums of money on their information needs, so publishers have worked with them closely when negotiating packages of products or have supplied libraries with regular subscriptions. These key accounts will have developed long-term relationships and will be used to pricing arrangements specifically suited to them; in certain cases, the overall price will be negotiated on the basis of a percentage rise in relation to their last year’s spending, rather than on totting up the prices (with discounts) of the products themselves. For some, standing order arrangements may be in place: for instance, some firms may pay a regular subscription and get a range of reports sent to them as and when they are written: rather than knowing what the content of the reports might be, they trust the publisher to produce interesting and relevant products for them. Some companies might be large enough to request a particular sort of product and the publisher can develop it for them, whether customising something it already has or creating something specific for that customer.

The new online products have allowed these key relationships to grow and become even more central to the sales business of the organisation. Online products can be grouped together in a range of ways and different levels of service can be provided, so ensuring that a much more complex set of product offerings can be produced; titles and services can be mixed and matched to provide the perfect library for a key account holder. As a consequence the product range has developed to be extremely flexible; while some technological work is necessary to select and structure the product, this can be crafted to quite a detailed level for a particularly important client. Thus publishers in professional fields such as law have become much more integrated into the work of their key account firms, supplying them with some sort of bespoke information that is necessary for them to work effectively.

The pricing for online products therefore becomes much more about issues of size of company, number of users, value of the information for those users and customisation than about lists of specific products with attached price tags. The firms need the publishers, who are expert at organising the information (expertise they developed with the print forms), and the publishers need the firms to purchase these works, which are expensive to produce and even more so to customise.

This symbiosis can have dangers. The importance of these customers is critical so publishers must maintain a good relationship with them; one of the ways of doing this is to ensure the other aspects of their service are good as well, not just their product offering. The ability to fix technological problems and provide additional service supporting use of the products, for instance, is important, as may be the way the way the products are integrated into the business. Some areas of professional publishing will have experts who go into companies to advise them on their information needs or create bespoke taxonomies or archiving systems for them. The latest issues are around integrating the use of information directly into workflow, something we will look at a little more on p. 58.

All this can mean additional revenue (though there are related costs as well in terms of time and skill), but where a company changes in some way, so can its budget; firms of this scale rarely entirely fall out of the market, but mergers and acquisition can leave a publisher vulnerable to a reduction in spending as companies consolidate resources, or downturns in the economic climate can lead to large areas of budget spend, such as for information needs, being threatened where cost cutting is required. The relationships with these customers therefore have become more entwined than before.

Medium-sized customers

Professional publishers may only have a certain number of very large customers that merit this sort of attention, so a more standard set of reference packages is available that medium-sized customers may well buy. Sales effectiveness was an area that needed more careful development in this sector. Key customers already had a much more personal service, and while reps covered these medium-sized businesses, the usual fliers and direct mailings in between reps’ visits were not enough to sell complex products. Sales leads development might lead to a sale in a print product but an intermediate stage with demonstration and training became part of the sales process for a digital product in the early days.

Flexibility in being able to design product offerings that match well to customer groups is important as there will be less opportunity to customise these. These packages have to make sense for the customer so that they do not have to buy into material they do not really need; early mistakes were made in packaging up selections of titles for this sector of the market. Pressure on libraries within medium-sized companies means they will look carefully at the pricing options as well.

Other customer groups

There are customer segments that contain buyers that are:

- specialist users – they operate in a niche where they depend on key works but may not need to purchase many to satisfy their needs; they may well be early adopters

- individual users – where the average value of what they buy is low and they may be a mixture of early and later adopters

These customers, when added together, may represent a lot of money and can easily have been loyal for many years, but individually do not merit a lot of work developing relationships and bespoke customer service as described above. These customers can be more difficult for a publisher to manage effectively. One of the traditional ways to keep some sort of communication going with them has been developing newsletters that are sent out regularly either with regard to a specific product or about the business environment in general, allowing for a marketing relationship with this group. The advent of new online products has allowed publishers to develop these connections much more quickly and easily to keep in touch with a customer base and try to provide a more customisable service on a wider scale for customers who are not necessarily commanding a large amount of budget.

Market research for product development

Market research is essential to developing high-value products and in the early stages of digital products there were some problems building a useful picture of customer needs. At first getting commentary from customers on what they wanted in a digital product was difficult given that many customers did not feel they understood what they might be getting. Now this would seem unlikely as everyone has had experience of the internet, which has become routine in their lives. But in the early development of digital products in the early to mid-1990s the internet was new and customers did not necessarily know how they might use it or what the limitations might be to a desktop product. Expectations ran high, which did not help the rather simplistic early products.

Different approaches were taken to solicit information, such as conjoint analysis to understand decision-making behaviour when choosing and building up packages, but these could be too complicated for customers new to the area to understand. These worked better for corporate librarians, who were already sophisticated users of databases and did understand the options; closer work with them, understanding the way products were used, was important.

Learning about how the market research process needs to work has been important, as has the scope of research in learning what is necessary to adjust selling and marketing techniques around digital products. However, research activity is now much more embedded in the continuous relationship between customers and new product developers.

Approaches to product development

The products that were developed over the last decade could be summarised as taking two main approaches:

- Horizontal approach: where products of a similar type were brought together (often based around central databases and data warehouses), such as all case law or all updated statutes or archives of news articles. Comprehensiveness was the key issue here, so a customer wanting to ensure they had access to a wide range of cases across many legal areas could buy into a case law product section.

- Vertical approach: which took a particular area and supplied a range of different materials that could be integrated to provide a one-stop shop for all information requirements for that particular area. So, for instance, you could have an intellectual property site, which would have statutes and legislation, case law, annotated law (i.e. law selected and critically examined by experts), news, journal articles, etc. Similar approaches are taken in other professional areas such as finance or regulation. Understanding job roles and functions more precisely is important here as complex digital products are built up for different uses.

Early pricing problems

In the early stages of these products the pricing often reflected a naivety about the electronic version, partly because of the migration expectations, as we have seen, and partly because of the added value provided by the digital version. The idea was that customers would substitute their print product for the digital – but would be willing to pay a higher price given the benefits of searching, up-to-dateness, etc. that the electronic version provided. With this in mind prices were generally at a standard percentage higher than the print version. Thus publishers hoped that the premium of the electronic version would allow for them to extend the value of each customer account without necessarily adding new product lines. That would help support the cost of the development.

While libraries did not necessarily assume that the development of digital meant huge cost savings for publishers (they knew the value of the information itself was the critical factor in the cost of a product), they still did not automatically expect to pay more for the product. Customers often stuck to the print version on that basis as it was cheaper, contained the same content and was without the failings of the early electronic version. In any case, many libraries wanted to keep a copy of one print version as the main reference, with the electronic version essentially enabling easy access for multiple users, saving space.

Pricing the bundle and subscriptions

This led to a growing sophistication in the price offerings as the bundle became more critical to the sales forces than the expectation of direct migration. The advantage of this approach was that the digital version became more integral to the total package and actually eased migration, given it happened more slowly and in a more integrated way, once it was accepted migration might not be total. The main complexity about this issue was that the package had to be unpacked in some way or other in order to calculate the VAT that was due on the electronic aspect of the bundle.

Subscription pricing was already well established in the legal reference market for regularly updated materials so the concept of pricing for a subscription for an electronic service was not a huge leap (unlike in other markets, as we shall see in Chapter 8). However, there were some issues. The early CD-ROM pricing mechanism was more complicated, as essentially to get an updated CD you had to buy the whole electronic product again each time so it was up to date (whereas with the print product you bought the main work just once, and simply subscribed to the service afterwards); this meant service charges for ongoing CD purchase, once you had bought in to the product initially, were higher than many customers expected. The development of online systems finally ended this problem, which could stimulate many customer complaints. However, it is an important lesson in understanding the way a product’s structure or format can determine an approach to pricing which in the end is counter-intuitive to the market. This is something that continues to recur throughout the industry as pricing remains a knotty area for digital publishing.

Licences and pay per view

The initial sales often focused around licences, with complicated fixed price menus of pricing and discounting based on numbers of users that were paid on top of a base price. While everyone understood the importance of transparent pricing, pricing was inevitably getting more complicated with the alternative ways of buying into what was at heart the same product.

There were also discussions with regard to pay per view options compared to buying a subscription. This essentially arose where the expense of buying a complete subscription could well be beyond some customers whose rate of usage was as yet undetermined, so pay per view options were built in. Some of the issues here were really around the newness of the products to customers who could not at that stage be sure how useful the product would be. This also stabilised once the customers started using them, as they could get a better feel of the value of the product to them and so develop a greater sense of what they might be willing to pay.

Customised pricing

These pricing issues largely settled around subscriptions packages with pay per view or pay per use options. The e-commerce and access management technology developed quickly enough to be able to accommodate flexible options, and the products today can be used and paid for in a variety of ways. However, one can quickly note that when searching for prices on a specialist publisher’s website it can be difficult to find a clear fixed price. Pricing is perhaps less transparent than it was, despite it being more flexible, as pricing has become much more tailored to the customer. This builds on what was outlined at the start of the chapter in relation to the sorts of customers for these products and the value these customers place on them.

Large corporates can normally be sure a large database will get used somehow or other and so accept it is worth paying the publisher for this information. The question therefore for publishers is less about the need to make prices attractively low in order to capture a market (though of course competitive pricing is still important) and more about determining value in the quality and usefulness of the information in digital and print formats to those companies. They do not want to underestimate its value nor price it to jeopardise print revenues. So analysis of the way companies use the information and review their current library practices is important in order to assess prices. The size of a company, the number of likely users, global reach, etc. all have to be taken into account when agreeing a price. As the purchase decisions are based around much bigger bundles and customisation, customers also need to get a better idea of their own usage (helped with the analytics provided by the publishing company).

Customers and publishers have had to get a better sense of how to value the information they provide and, as such, have arguably become much more closely knit. It used to be the case that if something new was bought by a library it might have to cut something off its list. Now packages can be designed that maybe include less critical information for free as a taster for the main deal. In fact understanding the financial make-up of a large company has become important, as the overall spending is often looked at and a publisher might target an ideal percentage uplift on the value of that account year on year, regardless of what was specifically included in the package; it can then adjust the package, add in more, etc. to gain the deal. Of course, as with any negotiation both sides need to be happy with the deal, so it was not always one way but a collaborative approach to negotiating might evolve. This is similar to any library purchase for a large database-style product, but at the high end of the corporate market the opportunities for customisation become more key to a deal.

There are lower prices for smaller customers and package deals with fixed prices and discounts for those who are not able to command large budgets or may require the more specialised vertical products as well as the educational prices noted above. Differentiated pricing had always existed but it has become more critical.

Building on existing products

The ongoing cost of the support and development of a database that is only ever expanding is an important one for publishers. They need to ensure they are satisfying their customers as far as possible in order to ensure the necessary revenue is still coming in. This requires a programme of continuous improvement for the products and services.

With the core digital products one of the obvious ways to develop the product is to build add-on services either which form part of the core product (making it all the more central to the customer by becoming ‘have to have’ material) or for which they can charge a top-up premium. The digital environment allows for suites of add-ons to be developed from email alerts, selected digests, expert commentary on newsworthy events, even easy ordering for print on demand for transcriptions.

Access levels

Access is also something that can be manipulated to add value to products. Customers can pay extra for additional levels of access, maybe for particular resources they only need at certain times; or they can be allowed to search across a wider range of databases than they currently have direct access to, and pay for additional material they find they need at that point.

Tailored products for market segments

One of the benefits of structuring the documents and the database carefully is that content in the data warehouse can be exploited in different ways to develop new products. In order to do this, further segmentation of the market is becoming more critical; to tailor products effectively the publisher needs to understand the requirements of each segment and target new products appropriately. Pricing and content can be very carefully managed to suit exactly that market. Growing subtlety in segmenting markets is becoming important. In many cases publishers have been simplifying the marketing of the offering, consolidating their lists around key brand names (such as Lawtel or Westlaw) rather than breaking it down into lots of smaller separate digital products. Some of the material will be the same behind two different branded products but directed in different ways for different types of user.

Flexibility of use

Large digital databases offer clear benefits for those looking for a comprehensive approach to legal information, but there are still parts of the business that focus on books. The print versions of titles continue to be successful for highly specialised customers who many not want online packages of products. Simple ebooks replicating the print products are usually available too. Large online databases are also cumbersome to use on the move and ebooks in app-style formats are being developed to make them more useable.

Products are being developed to be used in particular ways according to the sort of material they contain. An example would be an ebook designed to be viewed in an app environment where it is easy to bookmark pages, add comments, highlight significant cases, gather key information together as well as allow for easy searching anywhere, any time. Here publishers are getting closer to understanding the exact way content is used (rather than what the content is for) and designing a product with that in mind.

The White Book is an example of a major work that presents civil procedure rules for lawyers and barristers, written by experts and established over many years as an essential and authoritative source of information. In terms of migration to a digital product a rather specific issue around migration emerged as there was a convention of referring to the print product during a court hearing. When the first digital versions of the White Book were under development, neither online access nor controlled digital access was allowed in court. Knowing the peculiarities of your own market therefore becomes critical as print versions can still play a critical part in some aspects of user behaviour.

Alongside the print version, there is online access available on Westlaw as well as a CD version. However, the way the book is used is significant. In many cases users will want to add their own annotations, mark in highlights, refer to particular sections regularly, stick in Post-It notes and tabs to mark sections; portability is also key, which can make internet use of the work more cumbersome. This very physical way of using the book is important so the publishers have developed a professional grade iPad ebook which allows the book to be used in a way that mimics this with digital interactivity. They also dealt with the portability issues as an iPad was lighter than a heavy print volume. The book therefore is available in a wide variety of formats, some with different additional materials to add value to different degrees and allow customers a range of options to choose from so they can have a package that exactly suits them.

Newer digital products and the old dilemmas

Print and price still continue to pose challenges. While developments in apps and other ebook formats are growing in number, the pricing here is, as in the early days of the online products, not yet settled and may require refinement as the new offerings are taken up. For instance, a large print book product bought as an app product (which allows for portability and interactivity) can be offered at the same sort of price as the original print book, bought instead of the print; if this is the case, are the additional benefits being undervalued as there is no uplift on price, or, since the essential content is the same, does this matter? Meanwhile, the digital version can be bought as an upgrade on the main print product; if these prices are not calibrated carefully with the print-only and digital-only prices it can seem as if the deal is actually about having the print as the add-on premium to the digital rather than the other way round. So the pricing questions continue.

The dilemma of print also continues. Publishers are reducing their print offerings but see that there is still an extremely high-value market there. Publishers are continuously re-evaluating their print markets and the current migration patterns to online. The cost of the online products may also mean there are challenges in supporting the print side of the business, and more structural changes may need to take place as the old print-based departments may need to be reinvented as content development departments.

One problem for a publisher is that, broadly speaking, it can only offer what it has. The major players own proprietary systems that work with their data warehouse and maintaining the quality of those warehouses is critical – adding to them continuously and developing new content silos. It is important to be comprehensive in your offering so customers do not need to go outside. Where this is not possible information can be licensed in and smaller specialist publishers may be able to benefit in that way. Big customers will usually have more than one of the biggest services, and understanding the strengths and limitations of each is important. Nevertheless the drive to comprehensiveness may have an effect on the market. The larger players may have to buy companies to gain ground in a particular field in order to be competitive – whether a discipline or a market sector – and the market may then consolidate to a small number of companies.

Providing information services

Publishers in the professional arena are beginning subtly to change their emphasis. The following reflect these developments:

- Workflow: use of the content has become a feature of the current developments. Information such as this is used in certain ways at certain times within the development of a law case or a planning appeal. Seeing how the information is used gives publishers new ways to structure information in the best way for the user. The more it can be integrated into the daily work of the user, the more valuable it becomes.

- Chargeable useage: another aspect of understanding workflow means that, as with chargeable work, being able to identify when and how something was used in a case means that the price for that use of legal material can be charged to the legal firm’s client appropriately.

- Convergence: as publishers build their content more closely into the workflow of individuals there is a convergence between the content and the daily activity of the user so that the information and the application of it are more tightly tied together. The boundaries between information and its use are blurred, and the publisher and user are therefore becoming more embedded.

- Integrated CMS: complete customisation is difficult and costly to do for every customer, but for larger customers bespoke work can be done, tailoring information to their needs, building it into their content management systems, allowing for collaborative work and integrating it into their charging systems.

- Information consultants: what this means is that publishers need to work even more closely with their customers and in many ways begin to act as information consultants with the in-house information experts to ensure they get the best use out of their content. They become part of the competitiveness of a firm – if they can get the job done the best way possible, which includes using their information effectively.

- Other businesses: from this sort of integration it becomes easy to see other opportunities, such as the development of training packages providing continuous professional development (CPD); the effective use of information itself is becoming an important part of CPD. Other opportunities include providing boiler plate materials for daily use in constructing documents. In this way some publishers are reinterpreting themselves as wider service providers for the industry.

For some, the development of digital publishing has been a catalyst that has reignited the specialist reference sector, opening up a lot of opportunities in a marketplace that had become more static around core print products. In every sector the digital environment is leading to new approaches to the role of the publisher as relationships with customers change and products become more flexible, taking publishers into new directions. In this case the larger publishers have been developing extensive and sophisticated databases on which to build new products. The advantage for the specialist reference sector is that the publisher has always had a close link with its customer and has had highly valued expertise at developing content for the market. This will continue to be vital for the sector in the future.

www.outsellinc.com – a consultancy supporting the information and publishing industries, particularly in the professional and education arenas, providing useful reports and surveys

It can be useful to explore professional reference publisher sites to examine their digital product ranges. Here are some examples:

www.informabusinessinformation.com

- What challenges will publishers face as they develop increasingly sophisticated platforms for their information and how might they overcome these?

- Some see publishing as moving towards becoming an integral part of the way a company that it serves does business. What are the opportunities and challenges for the publishers who move in this direction?

- Will there be areas of the market that might lose out as publishers develop more bespoke expertise for their large professional clients?

1 Rogers, Everett M. Diffusion of Innovations. Free Press, 1962.