Futurising publishing structures

Throughout the book we have seen how the digital environment has created huge challenges for publishers. Many commentators have concluded that publishers will need to reconfigure their traditional activities in order to face these challenges effectively. This final chapter looks at:

- The changing elements of the value chain

- Reorganising publishing structures in the specialist sector

- Predicting change in the trade sector

The development of the digital environment for publishing has brought about many changes for publishing, whether reorganising the production process around the digital workflow and asset management systems or reconfiguring the activity of a marketing department to integrate social media practices. There is an increasing pressure on price and new market entrants are staking claims on the publishing of content. Each aspect of publishing that we have explored in Part III of the book has led to the conclusion that publishing as an industry needs to rethink some of its fundamental behaviours. New business models need to be developed quickly. And where a business model changes, all the elements of that model may need review, from discounting and sales practices to royalties and content development.

There is the additional impact for those businesses that have not had to make any major structural changes in any regular way: the legacy they carry of an infrastructure, honed over decades to traditional publishing practice, means change is both costly and cumbersome to implement. Newer players in the market can benefit in various ways: they do not have to carry the costs of any old infrastructure; they can ignore part of the market altogether (e.g. the print market); they can be nimble either through the low entry costs if they operate at one end of the market (e.g. self-publishers) or by commanding huge funding for investment that outweighs the financial strength of many large publishing houses, as the large technology companies can.

The question is complicated further by the fact that that legacy is still necessary for the time being. Print books still represent the larger part of global sales and even as sales slow down they will continue to be significant; so retaining aspects of the traditional infrastructure is still relevant, whether promoting relationships with bookshops or ensuring warehouses operate effectively. Publishers therefore cannot throw out everything with the aim of reinventing themselves for the new digital age, yet many observers agree that tweaking at the edges is not going to be enough.

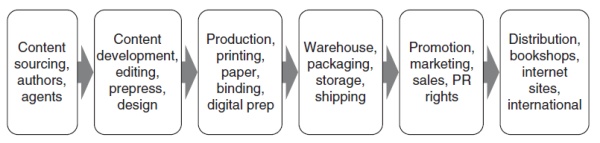

Changes in the traditional value chain have been a theme throughout the book. Figure 14.1 shows a simple value chain for publishing. Finding the content, the development and production, then the promotion and distribution of that content are all aspects of the publishing value chain where the involvement of publisher is clear. The publishing structures that have developed for this are very effective in the print-only world. As we have seen, some of these aspects of the value chain are becoming redundant – warehouses, for instance, are not necessary for digital-only books. Also other sorts of companies can have more involvement in or access to aspects of the value chain, thus meaning that publishers are no longer unique in providing these services. As certain elements of the value chain are eroded, so the structure needs to adjust.

But it goes deeper. Internet commentators who promote democracy and freedom for distribution on the web can sometimes suggest that publishers are the enemies of their ideal for free information as they want to control the process; others, meanwhile, will see that there are still important roles that publishers need to play but they may have a different emphasis from the traditional value chain. So, for instance, when bookshops are playing less of a critical role in the distribution of information, and anyone can become an author if they wish, the importance of selecting, or curating, content of a suitable quality (for whatever genre) may be gaining ground, as is the focus on marketing in order to obtain maximum discoverability. So the value chain can be reoriented to some extent through this sort of nuance: good content selection and effective marketing. But the fact remains that competitors moving into the market will have different structures and different approaches to the value chain which are much more fluid; as the traditional business of publishing begins to break down, publishers are considering ways to re-engineer it at a more fundamental level.

Challenging and reorienting the traditional value chain

If one takes a simplified version of the value chain one can then examine each area and question its place in the digital publishing environment. Below are just some of the issues and questions that arise with each part of the chain. This is not intended to be a comprehensive discussion, but the list encompasses the debates that have arisen throughout the book. It is, however, clear that each area can generate considerable debate about the role of publishers within that particular function:

- Content sourcing: authors can publish themselves and reach readers without much intervention – though they still need a digital intermediary such as Kindle Direct Publishing. Selecting and competing for good content therefore is changing. Publishing was always possible for an individual willing to pay for the individual components of the process and put in the time and effort required. However, economies of scale, extensive marketing departments with key networks and contacts gave publishing houses a lead. But things are getting easier and less expensive, enabling more people to do this, so the value chain is more exposed. Still publishers may provide the best and most direct route for customers to reach good-quality content.

- Textual/structural work on content: this still needs to take place, though it can be done without the need for publishers, using freelancers and communities to help self-correct. However, publishers may be the best at doing this given their experience – for some the beauty of having an editor work on a piece of writing is becoming clearer now that more poorly edited content is prevalent; whether editors ensure content is free from errors (so increasing its credibility), at one level, or work on the structure to make the content the best it can be, they add value. Editorial work can be done more quickly with digital methods. Speed to market is impeded by too much interaction with the text and if stages can be skipped (and fewer stages allow fewer mistakes to creep in), then digital puts pressure on this aspect of the chain.

- Production: various stages of production can take place without using traditional methods and the whole process can be managed more quickly. However, publishers have developed considerable expertise in managing digital content. Being able to manage content flexibly and to archive it for easy access in the future, make it discoverable with good metadata or repackage it in different ways, can, of course, be a huge advantage. For those involved in self-publishing the technology aspects of going digital without the help of experts can be time consuming and frustrating.

- Distribution: this can be physical and digital. Where physical products are needed, publishers are likely to be the best at doing this given their long experience and well-developed infrastructure, but digital distribution does not necessarily require a publisher given the various intermediaries that are available to use instead. As long as you pay for the technical help/software (or indeed use free systems such as open source blogs), distributing content digitally is easy. As the move to digital becomes more marked, the need for warehousing, for instance, will change; even for print books easier, just-in-time printing and local printing will mean warehouse strategies will change.

- Global distribution: the digital world brings everywhere closer as instant distribution globally is easy. This means the publishers who would add value by facilitating global distribution by selling rights or by shipping and selling physical books through a well-developed network of agents and international offices are less critical as these markets can be reached much more easily from one place. Nevertheless, discoverability remains an issue.

- Sales: bookshops are becoming less critical in the value chain given the pressure of getting cheaper print books from other intermediaries (from digital retailers to supermarkets) and in terms of the ability to promote and distribute ebooks. Publishers need to develop new relationships quickly with the new digital intermediaries, while also developing direct engagement with customers. Clearly a publisher will not be able to have much of a direct relationship with all its customers across all its product lines, but this issue reflects the need publishers have to move beyond the very close relationships they have with bookshops (though they must maintain those too as a valuable source of sales and promotion) and recognise that if they don’t do this they will lose more control over their marketplace. But all this throws the spotlight on the sales teams; they were the experts with the bookshops. With fewer bookshops sales functions are changing and integrating with marketing – as relationships with, for instance, Amazon need to be developed, relationships very different from the traditional bookshop relationship.

- Marketing: this can of course be done without the need for publishers. Much can be achieved using digital marketing practices now without large budgets. It is now possible for an individual to develop their own community of customers through successful blogs. It is a lot of work, however, and publishers have developed sophisticated ways to maximise discoverability within the digital environment as well as command impressive marketing budgets for big titles.

As these elements of the value chain change, so costs change – while production costs may come down due to less printing, the costs of marketing across so many more media can go up. Customer service departments have in many places grown as they take on more technical helpdesk roles to support specialist digital publications.

When you unpick the value chain in this way, even though it is not a comprehensive list of each stage, most of the key problems that publishers face surface. It also shows how far considerations related to the old value chain remain prevalent. New market entrants will be free of this history and in many ways able to create a value chain of their own according to their particular skills from a blank sheet.

The result is that existing publishers recognise the digital imperative is changing many aspects of the way they work and do business; they see they have to reorganise themselves to align with the changing market and review their publishing structure from the very roots. They need to look at what they can do, what they need to do and what they can’t afford to do any more; and they need to work out how to plan and pay for it. Publishers may need to strip back the value chain, taking out the parts that are no longer relevant, and to reconfigure what it is they do add in light of the digital environment.

Reorganising publishing structures in the specialist sectors

In the specialist sectors publishing structures have already changed in all sorts of ways. Such companies have gone through a more measured pace of reconstruction compared to the trade arena, partly because while technology has moved quickly it has done so reasonably evenly; greater market understanding of the content has also helped make the transition a little more smooth, without the upheaval that brand new mass consumer technologies have brought to the consumer market. Many have managed effective transfer of their business operations to cope with the new digital challenges. They have already had to revisit their skills bases and reorganise around the new requirements of a digital industry.

This has been managed in a variety of ways, as we have seen. Many have had units for a number of years in different countries to prepare content and manage the digital warehouse or supply services such as e-inspection copy management or helpdesks. Internally departments have been changed so that, for instance, they can expand and reduce staff numbers quickly and efficiently depending on their workflow. Expertise to plan for and cost big projects, project management skills, capability in creating product specifications for outsourcing and commissioning technical expertise are all examples of new skills and roles that specialist companies have expanded. This has meant a shift from the traditional desk editorial departments and some of the commissioning roles have changed, often focused on ongoing management expertise of large projects, keeping a commercial eye on their development and maintenance. Ultimately the ability to form and reform teams appropriately as technology changes or new projects come into view is at the root of some of the structural changes that have been made.

Other areas have, however, not had to change so much. Sales teams may have to become more technically literate about the products they sell and new sales activities around selling them developed (e.g. in providing training), but the sales team relationship with key clients remains at the core of product sales. Marketing departments have needed to encompass more social media marketing techniques, but close relationships with customers already existed and so it has been easier to grow these links within their traditional marketing activity.

Predicting change in trade publishing

For trade, the digital changes have been long awaited but only recently become much more of a critical issue as finally the sales of consumer technology reached a tipping point. Much more suddenly, the industry is facing the same problems that faced the specialist market. It is not just a case of foretelling when digital books will supersede print, nor for how long print will last – these questions are too general and do not quite go to the heart of the issue, say many industry experts. A change in format with different discounting patterns is less the challenge than the questions being asked of the real role of publishers in the internet age and the recasting of the fundamental business model.

Commentators review these questions regularly and pick out different aspects for chief scrutiny. By way of an example, a review of recent articles covers a variety of topics. Joseph Esposito, publishing industry consultant, in one article explores the fact that ebooks are being priced according to what the market wants to pay, which changes the business model; but he sees that ‘enhanced’ ebooks are a way for publishers to add value, while marketing is becoming even more of a driver for the business given issues of discoverability.

Richard Nash, a US-based commentator and publisher, believes that currently publishers are not doing enough to reorient themselves; instead they are only doing enough to minimise short-term disruption. The agency pricing issue might be an example – playing with pricing does not necessarily fit the company out for what appears to be an inevitable lowering of prices. The company needs to review its cost base and publishing practices in order to manage this new low-price model that others will exploit if they do not. He explains that more entrepreneurial approaches are needed from within publishing to compete effectively with entrepreneurs moving into their space. Supply in print or digital forms is reasonably easy to solve, but demand needs to be more carefully understood: the changing consumer is demanding information specific to their needs. In the old publishing model consumers had to choose from the selections the publisher put before them, but that has been turned around. Consumers will look elsewhere for information if publishers are not giving it to them in the way they want it, when they want it, where they want it. According to Nash, new skills such as data mining – making things discoverable – are going to be valuable as content becomes one gigantic data set; meanwhile intermediaries are changing – the search intermediary is becoming more important than, for instance, the retail intermediary.

Michael Healy, a US book industry professional, recognises that currently content is optimised for consumption in traditional book form but now thought needs to be given to the way content is commissioned, edited and formatted. The publisher’s role as curator and arbiter is important here. And here one should not read curation as only about high-level, culturally critical activity or sophisticated taste; celebrity biographies may have a role to play for a specific market in terms of providing enjoyment and interest. The actual nature of the book needs to be re-engineered and in the process new concepts explored around pricing models, for instance (as explored in Chapter 12) taking examples from other industries (such as all-in subscriptions – providing value-added services around free content). Healy is a proponent of the need for publishers to build some relationship with consumers – challenging though that is and maybe only of limited effect for a certain segment of the customer base – in order to watch reading patterns, which ultimately are where the change is coming from.

These are just three examples of commentators exploring publishing futures. One of the main messages that they share is that reinvention of publishing structures and the choices a publisher makes should not be based on the original value chain. Newer publishers aren’t bothering with bookshops, so are not having to calculate in discounts. A publisher may still need bookshops but may need to think of them in a different way (for instance as key partners for reaching the reading community) in relation to the new value chain.

Another point in common between these commentaries is that it is the consumer that is changing – the way consumers consume any sort of entertainment is changing rapidly and books are bundled into that mix in a much more complex way. The range of readers is expanding: there are those who are using social networks to share and create books with strangers, while at the other end of the market there are those for whom very private enjoyment of a book away from everything is what is attractive. This wide spectrum is going to prove a challenge.

Opportunities exist for publishers according to all these commentators – for instance, Nash points to the fact that there is the chance to explore different sorts of narrative alongside the long form, while Healy believes trade publishers can develop certain niche markets and build brands to become reader-centred businesses. Publishers often say when asked about their future that they recognise that they are in the business of entertainment and of creating communities. They are becoming producers across different media; they see the centrality of the reader in all they do; they should be regarded as creative specialists and can rethink not just design and format, but products themselves. Publishers are not behind on these new ways of thinking about what they do.

Nevertheless, in all these cases, the basic structure of the publishing company needs to be considered – can the old functional departments still exist? Will departmental lines blur (for instance between commissioning and marketing as content is created for a website and a book), or will new structures be invented, ones that take a hub approach, pulling in expertise as required for a particular project centre? New structures will need to be designed to be more flexible about external partnerships. Those who invest in new capabilities before a well-defined market has come into view will be the most able to cope: they may be developing digital archives that can be easily exploited in various ways; or they may be reviewing the way they produce the print to reinvent its role in the publishing programme; or they may be building partnerships that can evolve; or, as we have seen with Penguin and Random House, consolidating to gain strength in a changing marketplace. Whatever strategy they adopt, they need to ensure they are organised in a way that means they can exploit the potential of digital publishing most effectively in the future.

These are three interesting articles from good commentators on the future of publishing. There are many more like this to be found in journals such as Publishing Research Quarterly and Logos.

Esposito, J. ‘One World Publishing, Brought to You by the Internet’. Publishing Research Quarterly 27: 13–18 (2011).

Healy, Michael. ‘Seeking Permanence in a Time of Turbulence’. Logos 22/2 (2011). Nash, Richard. ‘Publishing 2020’. Publishing Research Quarterly 26: 114–18 (2010). Nash is a well-known commentator on the area and you can find interesting video discussions with him on internet sites such as YouTube and Vimeo.

Darnton, Richard. The Case for Books. Public Affairs, 2009.

- What functions do you feel a publisher will need in place to manage increasing amounts of digital products? And what will it need less of in the future?

- To what extent do you think specialist publishers are ready to face future challenges?

- How might you reconfigure a publishing company to be able to adapt to the changing business environment?

- What are the biggest threats and opportunities for publishers facing the digital publishing environment?