Chapter 10

Variation of a Trust and Setting a Trust Aside

Chapter Contents

Circumstances When a Trust Can Be Varied Today

The next topics concern whether it is possible to change a trust after it has been established and, secondly, when a trust can be set aside by the court even if, at first glance, it appears to have been validly created. This chapter builds upon the creation and operation of express trusts.

As You Read

Look out for the following issues:

![]() the common law and statutory authorities which permit a trust to be varied;

the common law and statutory authorities which permit a trust to be varied;

![]() the Variation of Trusts Act 1958, which is the main statutory authority, which enables the court to approve proposed variations of trust in certain situations; and

the Variation of Trusts Act 1958, which is the main statutory authority, which enables the court to approve proposed variations of trust in certain situations; and

![]() when a trust may be set aside if it has been set up to defeat or defraud a settlor’s creditors.

when a trust may be set aside if it has been set up to defeat or defraud a settlor’s creditors.

Variation of a Trust

Background

It has been shown that there are a number of requirements to establish a valid trust. To set up a workable trust, the settlor must:

[a] fulfil any formality requirements if the type of property to be left on trust requires it1 (for example, a trust of land must be evidenced in writing and signed by someone able to declare the trust under s 53(1)(b) of the Law of Property Act 1925);

[b] comply with the three certainties: intention, subject matter and object;2

[c] comply with the beneficiary principle;3

[d] adhere to the rules against perpetuity;4 and

[e] constitute the trust.5

These rules generally exist to provide some protection for the trustee. The first four criteria — relating to declaring the trust — ensure that it must be absolutely clear that a trust has been created, spell out categorically what it is that the trustee is supposed to administer and in whose favour the trustee must manage the trust. Constituting the trust ensures that the trustee can manage the trust property by transferring the legal title in the property to him.

If, however, the settlor has jumped through all of the hoops required in creating a trust, it might be thought that varying the trust would be very strange to him as he will have spent a lot of time and trouble setting up the trust and perhaps would not want those arrangements disturbed by their being subsequently altered.

The basic rule here is that, once established, it is not possible to vary a trust. This was explained by Lord Evershed MR in Re Downshire Settled Estates:6:

The general rule … is that the court will give effect, as it requires the trustees themselves to do, to the intentions of a settlor as expressed in the trust instrument, and has not arrogated to itself any overriding power to disregard or rewrite the trusts.7

Yet equity has always permitted a trust to be varied in certain circumstances. Originally, equity’s jurisdiction to alter a trust was used to deal with property or the management of it for children or mentally disabled individuals.8

Trusts nowadays tend to be established as a method of saving tax. Each year, however, the Finance Act following the government’s Budget makes changes to the taxation system. Consequently, an original tax-efficient trust that may have been established may have become less tax efficient than it was at the time the trust was set up. The beneficiaries might, therefore, wish to vary the trust to minimise their liability to tax.

Varying a trust to avoid tax can result in large savings to the beneficiaries. Such a variation occurred in Re Norfolk’s Will Trusts; Norfolk v Howard9 in which the sixteenth Duke of Norfolk successfully applied to the High Court to vary the trusts set up by his father. As a result of the court approving the variation, the beneficiaries of the revised trust enjoyed an additional £550,000 that would otherwise have been payable in taxation.

The court does not act as a slave to HM Revenue & Customs and is not predisposed to prevent variations of trust occurring just because their purpose is to avoid tax. In fact, the contrary is true, according to Lord Evershed MR in Re Downshire Settled Estates, in that it is:

not an objection to the sanction by the court of any proposed scheme in relation to trust property that its object or effect is or may be to reduce liability for tax.10

It is important to note, however, that a trust may only be varied when permitted and saving tax does not have to be a prerequisite to a successful application to vary a trust. The crucial issue is when it is permitted to vary a trust.

Circumstances When a Trust Can Be Varied Today

A trust may be varied using one of three main methods. Before the intricacies of each method are examined, a table setting out the main parts of those methods is set out in Figure 10.1. These methods only apply if there is not an express power to vary the trust contained in the

trust document for, if such a power exists, obviously it makes more sense to take advantage of that power.

Each of these methods must be examined in turn.

Varying a trust with the consent of all adult beneficiaries

If they act together, all adult beneficiaries are entitled to vary the trust provided that they all collectively enjoy an absolute interest in the trust property. They must all enjoy mental capacity. The result of a group of adult beneficiaries owning the entire equitable interest collectively is that the trustees hold the trust property on a bare trust. The ability of the beneficiaries to vary the trust comes from the decision in Saunders v Vautier,11 which gives rise to what is sometimes known as ‘the rule in Saunders v Vautier’.

Here, a testator left shares in the East India Company worth £2,000 on trust for the benefit of his great-nephew, Daniel Wright Vautier. There was a direction in the testator’s will that the income from the shares had to be accumulated (reinvested) into the capital until Daniel reached 25 years old. At that point, the capital of the shares, together with all of the accumulated income, was to be transferred to him. The testator died when Daniel was still a child.

In March 1841, Daniel attained 21 years old, then the age of majority. He applied to the Court of Chancery to have the whole fund (both the value of the shares and the accumulated income) transferred to him, four years earlier than that envisaged by the creation of the trust.

Lord Langdale MR agreed that the whole fund should be transferred to Daniel. He said that:

the legatee, if he has an absolute indefeasible interest in the legacy, is not bound to wait until the expiration of that period, but may require payment the moment he is competent to give a valid discharge.12

The moment when Daniel could give a valid discharge — or receipt — for the money was when he reached the age of majority.

The decision in the case turned on the fact that Daniel had an absolute interest in the trust property. The other residuary legatees argued that he had a contingent interest, an interest which he could only enjoy provided he reached the age of 25. The court rejected this argument. It seems it was on the basis that the testator had merely directed the income to be accu-mulated. He had actually given Daniel a vested interest in the shares but simply directed the income to be accumulated for his maintenance.

The decision in the case shows that beneficiaries who enjoy an absolute vested interest in the trust property may call for it to be transferred to them. In a sense, it is an example of a trust being varied but it is a rough-and-ready variation as it simply brings the trust to an end. As the trust was, in any event, a bare trust only, it is not a particularly significant step for the adult beneficiary to call for the trust property to be transferred to themselves.

The principle from Saunders v Vautier still stands but now applies to beneficiaries at a younger age. As a result of s 1 of the Family Law Reform Act 1969 being enacted, the age of majority was lowered in English law to 18 years of age from 21. That means that if a beneficiary reaches the age of 18 and enjoys an absolute vested interest in trust property, he can compel the trustee to transfer the trust property to himself. That transfer will mark the end of the trust. The ratio decidendi of the case also applies where there are a number of adult beneficiaries who collectively all enjoy the equitable interest in the trust property, provided they all have mental capacity.

Varying a trust under the court’s inherent jurisdiction

As You Read

This area is concerned with when the court has an inherent right to sanction a variation of trust on behalf of infants, those unborn or mentally incapable beneficiaries as those categories of people cannot give their own consent. Beneficiaries who are 18 years or over and mentally capable must continue to give their own consent and the court cannot override such beneficiaries’ wishes.

As will be seen, the extent of the court’s inherent jurisdiction to vary a trust is very limited and it could be questioned whether such a jurisdiction even exists at all.

The difficulty with the rule in Saunders vVautier is that it is of very limited application. It only applies to beneficiaries who:

![]() are all adults and who are mentally capable (‘sui juris’);

are all adults and who are mentally capable (‘sui juris’);

![]() all have an absolute, vested interest in the trust property; and

all have an absolute, vested interest in the trust property; and

![]() have no other desire than to end the trust by transferring the legal interest in the trust property to themselves.

have no other desire than to end the trust by transferring the legal interest in the trust property to themselves.

Before the decision of the House of Lords in Chapman v Chapman,13 the courts also thought that they enjoyed a much wider discretion to vary a trust if asked to do so, as part of an inherent jurisdiction that the Court of Chancery originally enjoyed. Quite how wide their discretion lay depended on the views of the individual judges.

The relatively wide view of the Court of Appeal

In Re Downshire Settled Estates, Lord Evershed MR, with whom Romer LJ agreed, whilst not wishing to impose ‘undue fetters’14 on the court’s discretion, thought that the court actually enjoyed only a limited inherent discretion (as a successor to the Court of Chancery) to vary a trust. This limited discretion enjoyed by the court was to enable the court to give the trustees such addi-tional administrative powers as were necessary for the trustees to deal with the trust property if an ‘emergency’ arose. Such administrative powers had to be used for the benefit of ‘everyone interested’15 under the trust. An ‘emergency’ was defined to mean something that the settlor had not planned for when setting up the trust as opposed to involving notions of extreme urgency in the need to vary the trust. It also had to be for everyone’s benefit that the court granted the trustees additional administrative powers.

Lord Evershed MR quoted from the example given in the judgment of a different Romer LJ in Re New16 of the emergency situation under consideration. In that case, Romer LJ gave the example of a testator creating a trust in his will giving a direction to his trustees to sell some of the trust property at a particular point in time. When that time arrived, the market for the property had fallen, which meant that complying with the testator’s wishes in selling the property would create a loss to the estate. He said that in such a situation, the court would authorise a power to be given to the trustees to postpone the sale of the property until a later date. Such an event was an ‘emergency’ because it was unforeseen by the settlor when establishing the trust. The court was able to intervene to grant further administrative powers to the trustee.

In Re Downshire Settled Estates, Lord Evershed MR said a wider exception existed where the beneficiaries were either infants or mentally incapable. In those situations, the court was able to step in more generally to vary the trust. This was because the beneficiaries were not adults and not, therefore, in a position to act together, so as to enjoy the benefit of the rule in Saunders v Vautier. In acting in this situation, the court would be permitting the variation of the interests of the infants or mentally incapable beneficiaries. Those who were adults and mentally capable would need to give their own consent. This was known as ‘compromising’ the claims of the infant or mentally incapable beneficiaries, which really meant the court was acceding to a bargain that the sui juris beneficiaries had put forward. The word ‘compromise’ was to be given a wide meaning and was not to be limited to settling disputed claims.

The third judge in the case, Denning LJ, took a typically more robust position as to when the court should be able to exercise its inherent jurisdiction. He believed that the Court of Chancery had enjoyed a jurisdiction to sanction any acts done by trustees for the benefit of either infant or mentally incapable beneficiaries provided the court was satisfied that the variation was indeed for their benefit. Given that, acting together, beneficiaries who were sui juris could agree to a variation of trust themselves, Denning LJ’s views would have given the court a wide discretion to vary a trust in the case of infant or mentally incapable beneficiaries: the variation simply had to be for their benefit.

The narrower view of the House of Lords

The decision of the House of Lords in Chapman v Chapman (handed down within 16 months of the Court of Appeal’s decision in Re Downshire Settled Estates) placed strict limits on when a court could sanction the variation of a trust.

The facts concerned trusts established by Sir Robert and Lady Chapman for the benefit of their grandchildren. The trusts contained substantial sums of money for their benefit, with the effect that upon the settlors‘ deaths, a large sum (approximately £30,000) would be due to the Inland Revenue in the form of death duties. A scheme was proposed by the adult beneficiaries and trustees under which money would be taken from the established trusts and transferred to new trusts which would omit the provisions that gave rise to the tax being charged. The court’s consent was needed on behalf of the infant beneficiaries.

The House of Lords refused to approve the scheme on the basis that the court enjoyed no jurisdiction to give authority to such a variation of trust on behalf of the infant beneficiaries. The House of Lords adopted a firm stance against the court having any jurisdiction to vary a trust and thought that any such ability the court did enjoy was by way of exception rather than the norm.

The most detailed opinion was delivered by Lord Morton. He believed that previous case law of when the court had sanctioned variations of trust under its inherent jurisdiction could be grouped together under four heads:

[a] the ‘conversion’ jurisdiction;

[b] the ‘emergency’ jurisdiction;

[c] the maintenance jurisdiction; and

[d] the compromise jurisdiction.

The ‘conversion’ jurisdiction

This jurisdiction concerns the ability of the court to sanction a variation of trust in converting the nature of the property to which an infant or mentally incapable beneficiary is entitled. For example, a trust might wish to be varied so as to allow the infant’s interest in personalty to be invested in realty.17 Lord Morton believed that the court had always enjoyed an inherent jurisdiction to sanction such variations of trust. Such a jurisdiction was uncontroversial and would continue to be permitted.

The ‘emergency’ jurisdiction

Lord Morton believed that the court did enjoy a jurisdiction to sanction a trust being varied on behalf of those beneficiaries who were incapable of giving their own consent but such jurisdiction was of an extremely limited nature.

He quoted with approval the comments delivered by Romer LJ in Re New. The facts of that case concerned three separate trusts set up by shareholders in the Wollaton Colliery Company Ltd for the benefit of their children. The originally priced £100 shares left on the trusts had increased substantially in value to be worth £175 each. The shareholders of the company wanted to reorganise the company so that, effectively, each of the shares would be split into smaller shares. Shares worth a smaller amount could be bought and sold more easily as they would appeal to more investors. This would be achieved by the creation of a new company and the exchange of the original shares for shares in the new company. All of the shareholders of the company were keen for the scheme to go ahead, as were the trustees of the trusts. The problem was that some of the beneficiaries were not s ui juris and could not give their own consent to the variation of the trust. The court’s consent would be needed if the scheme was to go ahead.

Even today, certain companies‘ share prices increase dramatically beyond initial expecta-tions when the shares are first issued. The best example nowadays is probably that of Apple, whose shares initially traded at $22 but were worth over $600 each in early 2012.

In giving the judgment of the Court of Appeal, Romer LJ began by stating the general rule that the court has no jurisdiction to sanction any acts that the trustees wish to undertake which are not permitted by the terms of the trust. However, the court could sanction acts which had to be done by trustees in an ‘emergency’. An emergency was one which:

may reasonably be supposed to be one not foreseen or anticipated by the author of the trust, where the trustees are embarrassed by the emergency that has arisen and the duty cast upon them to do what is best for the estate, and the consent of all the beneficiaries cannot be obtained by reason of some of them not being sui juris or in existence …18

But the court would exercise its jurisdiction with ‘great caution’19 and

will not be justified in sanctioning every act desired by trustees and beneficiaries merely because it may appear beneficial to the estate … each case brought before the Court must be considered and dealt with according to its special circumstances.20

On the facts of the case, the proposed variations of each of the three trusts were permitted.

The decision of the Court of Appeal in Re Tollemache21 (in which Romer LJ again sat) just two years later set out limits of the emergency jurisdiction considered in Re New. Cozens-Hardy LJ described the decision in Re New as ‘the high-water mark of the exercise by the court of its extraordinary jurisdiction in relation to trusts’.22 Vaughan Williams LJ said that the court could only exercise its emergency jurisdiction to sanction a variation of trust if the emergency had to be dealt with ‘at once’.23

Lord Morton approved the comments of Romer LJ in Re New and the decision of the Court of Appeal in Re Tollemache as setting limits on the extent of the emergency jurisdiction. He summed up24 the jurisdiction as being there to ‘salvage’ trust property rather than do anything more proactive in the management of a trust.

The maintenance jurisdiction

This concerns the court’s ability to provide for children of the settlor. If a trust has been created which directs the income from it to be accumulated into the capital, prima facie, any children of the settlor would not be provided for on a day-to-day basis from the trust fund. The court has assumed that such a settlor would not have desired their children to be destitute and so has sanctioned the maintenance of such children.

Lord Morton regarded this ability to provide maintenance as a limited exception to the principle that the court had no jurisdiction to vary a trust. He quoted, with approval, Farwell J in Re Walker:25

I decline to accept any suggestion that the court has an inherent jurisdiction to alter a man’s will because it thinks it beneficial. It seems to me that is quite impossible.

Lord Morton believed Farwell J’s words were ‘equally true in the case of a settlement’.26

The facts of Re Walker concerned a trust established by Sir James Walker in his will of 1882 in which he left a considerable amount of land in Yorkshire on trust for the life of his son and, in turn, each of his sons. The trust contained a direction that £500 per year should be used from the income of the land to maintain any infant beneficiary. This maintenance was to include the upkeep of the house, Sand Hutton Hall, in which each beneficiary was directed to reside. An infant beneficiary, the great-grandson of Sir James, brought an action to vary the trust so that £4,000 might be used from the income each year for his maintenance and education, arguing that £500 per year was insufficient to maintain such a vast residence as Sand Hutton Hall.

Although wary of altering Sir James’ will, Farwell J sanctioned the variation of the trust in this manner. The judge found that the will contained a ‘paramount intention’27 by Sir James that Sand Hutton Hall should be kept in good repair, but he had made no specific provision for maintaining the house. In addition, he found the will contained a separate allowance of £500 per year for an infant beneficiary’s personal maintenance, which could take the form of meeting the costs of the child’s education. As Sir James had not forbidden a larger sum being spent on the maintenance and education of an infant beneficiary when more was needed than he had provided for in the trust, the trust could be varied to reflect Sir James‘ intentions that the property and the infant beneficiary both be maintained appropriately.

Re Walker is a good illustration of the court exercising a jurisdiction to sanction the variation of a trust to maintain an infant beneficiary by providing a suitable place for him to live. But as the comments of Farwell J make clear, as supported by Lord Morton in Chapman v Chapman, the court’s ability to vary the trust in this manner is clearly limited. The court must find an intention of the settlor to maintain a beneficiary and, in that sense, the court is not really approving a dramatic variation of a trust. In Re Walker, the settlor had always made provision for the infant beneficiary; all that was in issue was the appropriate amount that should be apportioned to this maintenance.

Even if a settlor has made no specific provision to maintain an infant beneficiary in the trust, the jurisdiction here appears to be limited to trusts concerning the settlor’s family, according to Pearson J in Re Collins.28 It may be that this jurisdiction could be extended slightly although the prospects of that occurring are small. It is perhaps only a small step for the court to sanction the maintenance of a person that the settlor would have naturally maintained during their life.

Does Re Collins reflect modern day lives? Should the court’s jurisdiction be extended to maintain other children for whom, perhaps, the settlor has assumed responsibility during his life? For example, if the settlor has made his infant godchild a beneficiary under a trust in his will, should the court nowadays be permitted to vary that trust to maintain the child?

The compromise jurisdiction

Lord Morton acknowledged that there were ‘many’29 reported cases in which the Court of Chancery and the High Court had approved compromises in relation to infants or unborn children. This did not mean that the court enjoyed an unlimited jurisdiction to vary a trust, however, by compromising beneficiaries’ claims to the trust. Trusts which were potentially to benefit infants and unborn children were, at that stage, ‘ex hypothesi, still in doubt and unascertained’30 because their interests had not yet been ascertained. The problem arose when interests were ascertained:

If, however, there is no doubt as to the beneficial interests, the court is, to my mind, exceeding its jurisdiction if it sanctions a scheme for their alteration, whether the scheme is called a ‘compromise in the broader sense’ or an ‘arrangement’ or is given any other name.31

Lord Morton thought that the views of the members of the Court of Appeal on the ability of the court to approve compromises in Re Downshire Settled Estates were too wide. The court did not have any jurisdiction to approve contrived ‘compromises’ between beneficiaries.

Lord Simonds LC made it clear in his speech that the court’s jurisdiction to sanction a compromise meant that the court could only make a decision in the event of a genuine dispute of a beneficiary’s rights. A practice had grown up in the first half of the twentieth century in which High Court judges would, in chambers, approve variations to trusts on behalf of infants or unborn children. Disputes had often been manufactured by the parties to the trust as this was the only way to obtain the court’s sanction to a variation of the original trust. Lord Simonds LC disapproved of such a procedure as frequently it had simply been assumed that the High Court had jurisdiction to make such orders varying beneficial interests in this manner. As such hearings were in chambers, they were not subject to the transparency and scrutiny that decisions in open court enjoy. Lord Simonds LC believed that the only time the compromise jurisdiction should be used by the courts was in the case of a real dispute over beneficial rights and where the court’s consent was sought on behalf of infants or unborn children. In doing so, Lord Simonds LC disagreed with the comments of the majority of the Court of Appeal in Re Downshire Settled Estates that the word ‘compromise’ could be interpreted widely, to authorise the imposition of a fresh bargained agreement between the adult beneficiaries and trustees concerning all of the beneficiaries’ interests.

Summary of the court’s inherent jurisdiction to vary a trust

Following Chapman v Chapman, the court only had authority to sanction a variation of a trust in four strictly limited situations. These were in situations of conversion, emergency, maintenance and genuine compromise.

The difficulty with this conclusion was that it limited the court’s ability to sanction the variation of a trust on behalf of a beneficiary who was not sui juris. In doing so, it put an end to the practice of High Court judges in chambers approving such applications to vary a trust on a relatively informal basis.

As a result of the decision in Chapman v Chapman, the Variation of Trusts Act 1958 was enacted.

Variation of a trust under statute

Variation of Trusts Act 1958

This statute is the main method nowadays by which trusts are varied.The long title to the Variation of Trusts Act 1958 expressly confirmed that the purpose behind its enactment was to remedy the restrictive decision in Chapman v Chapman as to when a trust could be varied:

An Act to extend the jurisdiction of courts of law to vary trusts in the interests of beneficiaries and sanction dealings with trust property.

The Act thus sought to restore the courts’ ability to vary trusts to the relatively informal operation that had been carried out by judges pre-Chapman.

Section 1 of the Act gives the High Court32 two powers: (i) substantive and (ii) adminis-trative:

[a] the substantive power is that the court may ‘approve … any arrangement’ proposed by any person to vary or revoke a trust; and

[a] the administrative power permits the court to approve an arrangement which seeks to enlarge the trustees’ powers in varying or administering the trust property.

‘Arrangement’ was described by Lord Evershed MR in Re Steed’s Will Trusts33 as having a very wide meaning which would include ‘any proposal which any person may put forward for varying or revoking the trusts’.34

Taken together, the powers enable the court to sanction a wide range of variations of trust.

But the powers are curtailed because the court is not able to sanction arrangements for any variation of trust under s 1. The court can only give its sanction for a variation, revocation or enlargement of the trustees’ powers if it is doing so on behalf of a category of person who falls into one of the four categories listed in s 1(1). Those categories are:

[a] a beneficiary who is incapable of giving their own consent because they lack capacity (i.e. they are under 18 years of age or are mentally incapable);

[b] a potential beneficiary who may become entitled to an interest under a trust in the future. Such potential beneficiaries merely enjoy a hope (or spes) of being chosen to be a beneficiary and enjoy the trust property. The court may consent on behalf of such a person. If they have been chosen by the trustees to be an actual beneficiary, then the court can no longer consent on their behalf;

[c] an unborn beneficiary; and

[d] a person who may enjoy an interest under a discretionary trust but one which arises because there is a protective trust in operation and the principal beneficiary under the protective trust has not yet determined their trust. Once again, the discretionary beneficiary may or may not actually receive the trust property in the future, depending on whether the protective trust is determined.

Key Learning Point

The key point is that the High Court may only give its permission for a variation or revocation of a trust on behalf of a person who falls into one of the categories listed in (a) — (d). There is no jurisdiction for the High Court to consent on behalf of any other category of person.

Glossary: Protective trust

A protective trust in the 1958 Act is defined by reference to Trustee Act 1925, s 33. This defines a protective trust as one where income is invested for the life of a beneficiary. That beneficiary is then known as the ‘principal beneficiary’. The nature of a protective trust is paternalistic in that it seeks to prevent the beneficiary from gaining access to anything other than income from the trust. If the beneficiary seeks to take any action to gain any more than the income, the trust will immediately determine.

At the point of the protective trust determining, a discretionary trust comes into existence. The trustees enjoy a discretion to pay the income to a group which includes the principal beneficiary and their spouse or partner and issue or, if there is no spouse, partner or issue, those people who would be entitled to the beneficiary’s property on his dying intestate. Whilst the beneficiary might still enjoy some of the income under the trust, he may not now enjoy any as a result of the discretionary trust coming into existence and the trust property, instead of being solely his own, may now be distributed between a group of people.

The nature of a protective trust is, therefore, to protect a beneficiary against dissipating the trust property. If he simply accepts the income from the trust, he will be entitled to that for his lifetime or any other period the settlor may have stated in the trust. But if he tries to vary the trust so as to enjoy the capital as well, a discretionary trust comes into existence under which the income from the trust property may be shared between a wider group.

Suppose Scott creates a trust and appoints Thomas as his trustee. The trust provides that £100,000 is left on trust for the benefit of Ulrika for life remainder to Vikas. Ulrika is 25 years old but Vikas is only five years of age. Scott dies the following day.

Ulrika decides that she would like a little more freedom with the trust money but she does not wish to deprive Vikas of his fair share. She proposes that the trust be varied so that they both become absolutely entitled to £50,000 each.

The High Court could give its consent on behalf of Vikas as he falls within category (a) of s 1(1). Vikas is not able to give his own consent to the proposed variation as he lacks capacity due to being an infant.

If, however, Vikas was 18 years of age or older and enjoys mental capacity, there is no jurisdiction for the High Court to consent on his behalf. Ulrika would need to seek his own consent, under the rule in Saunders v Vautier. The trust would then end and both of them would enjoy their shares. If Vikas refused to give his consent, then the trust would have to continue.

The final criterion under s 1 is that for the court to approve any arrangement brought before it on behalf of those categories of people listed in (a)–(c) it must be shown that such an arrangement is for that person’s benefit. The requirement to demonstrate that it is for a person’s benefit does not apply to the court giving its consent on behalf of those individuals falling into category (d).

‘Benefit’…

The requirement that the variation or revocation of the trust or enlargement of the trustees’ powers be for the ‘benefit’ of the person on whose behalf the court consents under paragraphs (a)–(c) of s 1(1) is a real one and not one to which the court simply pays lip-service, as was shown in Re Weston’s Settlements.35

The facts concerned two trusts set up in 1964 by Stanley Weston, one for each of his two sons and their respective future children. The trust property was shares in a public company. In 1965, Capital Gains Tax was introduced by the Government which would have resulted in a heavy taxation liability when the shares were sold. However, tax could be avoided if the majority of the trustees and all of the beneficiaries were not resident in the UK. To save tax, Stanley and his family moved to Jersey.

Located just 14 miles off the coast of northern France, Jersey is a ‘peculiar’ of the English Crown. Originally owned by William of Normandy (later William the Conqueror), the island allied itself to King John of England in 1215 as opposed to being ruled by France. Loyal to the English Crown since, it has its own separate legal system which has its roots more in Norman-French law than that of the English legal system. Its residents enjoy lower taxation than their English counterparts, which means that it remains an attractive jurisdiction to this day for the establishment and management of trusts.

Stanley brought an application to bring the two trusts under the control of Jersey’s legal system and for the trust property to be transferred to trustees resident in Jersey. This was really an application to revoke the original trusts, made under English law, and reconstitute them under Jersey law. The elder son gave his consent for the trust to be revoked in this manner. The younger son was an infant and so lacked capacity to give his own consent. The High Court was asked to give its consent on his behalf under s 1(1)(a) of the 1958 Act. As the trusts were originally established for the benefit of the two sons‘ own children, permission was also sought for the High Court to approve the revocation of the trusts for these unborn children too, under s 1(1)(c).

The High Court refused to give its permission to revoke the trusts in this manner and the Court of Appeal agreed with its decision.

Giving the leading judgment in the Court of Appeal, Lord Denning MR pointed out that the 1958 Act gave the courts no guidance as to when a variation or revocation of a trust should be sanctioned under it. In making a decision over whether to agree to a variation or revocation of a trust, he said that two propositions were clear. The first emphasised that any consent given by the court to vary or revoke a trust had to be for the individual’s benefit, ‘[i]n exercising its discretion, the function of the court is to protect those who cannot protect themselves. It must do what is truly for their benefit’.36

The second proposition was that it was an acceptable benefit to be the avoidance of taxation. As Harman LJ put it, the court’s function was not to be ‘the watch-dog of the Inland Revenue’.37

Lord Denning MR defined ‘benefit’ widely. Whilst ‘benefit’ could mean financial benefit to infants or unborn beneficiaries in saving tax through a variation of a trust, it also concerned social and educational benefits of the proposed variation, which had to be considered too:

There are many things in life more worth while than money. One of these things is to be brought up in this our England, which is still ‘the envy of less happier lands’.38

When considering ‘benefit’ in terms of the children and unborn children’s social and educational upbringing, Lord Denning MR did not believe it was for their benefit to be ‘uprooted from England and transported to another country simply to avoid tax’.39 On the facts, the family had lived in Jersey for only three months before they made the application to revoke the trusts and to bring them under Jersey law. There was no evidence to say that the family would remain in Jersey for any length of time. Lord Denning MR did not think it was right to encourage the revocation of the trust as to do so would effectively sanction the uprooting of children on an on-going basis to different jurisdictions depending on which legal system offered the most attractive taxation regime. Such continuous moving could not be considered to be for the children’s ‘benefit’. Whilst taxation avoidance was lawful:

[t]he Court of Chancery should not encourage or support it — it should not give its approval to it — if by doing so would imperil the true welfare of the children, already born or yet to be born.40

The case illustrates that avoiding paying tax can be a valid benefit for which the court will sanction a variation or revocation of trust. But such a benefit must be weighed up against the other disadvantages of the proposed variation. Social or educational disadvantages connected to the proposed variation or revocation can outweigh the taxation benefits.

Less than a year after the decision in Re Weston’s Settlements, however, the High Court did sanction the revocation of a trust under English law and the re-establishing of it in Jersey in Re Windeatt’s Will Trusts,41 but the differing facts meant the court could take a different view on ‘benefit’.

The testator, Thomas Windeatt, wrote his will in 1951 in which he declared a trust leaving the income in the trust property to be paid to his wife during her lifetime with remainder to their daughter Mary and her children. Thomas and his wife had always lived in England. Mary lived in Jersey with her husband and children. After the death of her parents, to save tax, Mary brought an application seeking the same revocation of the trust as in Re Weston’s Settlements — that new trustees (residents of Jersey) be appointed to administer the trust and that the trust be re-established in Jersey.

Pennycuick J approved the application made to revoke the trusts under English law and to re-establish them in Jersey. He believed the facts before him enabled him to distinguish Re Weston’s Settlements easily. Unlike in Re Weston’s Settlements where the family had moved to Jersey shortly before the application to the court to revoke the trust, in the present case Mary and her husband had lived in Jersey for 19 years. Their permanent home was in Jersey. Their children had been born on the island. Following Re Seale’s Marriage Settlement,42 an order would be made revoking the trust under English law and permitting it to be transferred to Jersey’s jurisdiction.

Pennycuick J did not consider ‘benefit’ in any detail in his short judgment but it must be clear that he felt that the benefits to be saved in reduced taxation in moving the trust to Jersey did not come into conflict with the children’s social or educational benefits. There was no suggestion that the family was seeking to move the trust purely for taxation advantages. It made sense that the trust should be administered in Jersey given that the family’s life was there. The taxation savings were a benefit but, unlike in Re Weston’s Settlements, there were no adverse social or educational consequences to varying the trust which conflicted with the benefit of avoiding tax.

The concept of ‘benefit’ was examined more broadly by Megarry J in Re Holt’s Settlement.43 Here, Alfred Holt declared a trust of £15,000 from which income was directed to be paid to his daughter, Patricia, for life with remainder to her children that should attain 21 years of age. Patricia had three infant children at the time she made the application to the High Court to vary the trust. The original money had been invested in company shares which had grown to be worth £320,000. In order to save tax, Patricia wanted to give half of her life interest to her children but to postpone the children’s entitlement in their capital interests until they reached 30 years of age. Her reasoning behind increasing the age before their entitlements became vested in them was to prevent them from being entitled to substantial sums of money at the comparatively young age of 21. The variation was to be carried out by revoking the trust declared by Alfred and establishing a new trust. Patricia needed the High Court’s consent to the variation on behalf of her current children and any future children she might have had.

Megarry J recognised that the children might be subject to a financial detriment by having the age at which the property was to vest in them postponed by nine years. Yet against that could be weighed up the advantages of the general proposal: the savings of tax were substantial and the children would also enjoy additional money when their interests did vest as Patricia was surrendering half of her life interest to them. Such benefits here were overwhelming and the High Court would give its consent on behalf of the children and any future unborn children.

In terms of ‘benefit’, Megarry J believed that, ‘[t]he word “benefit” in the proviso to section 1 (1) is, I think, plainly not confined to financial benefit, but may extend to moral or social benefit … ’44

In terms of approving the arrangement for unborn children, Megarry J held that the court should be prepared to authorise the variation on their behalf if such arrangement was one in which there was at least likely to be some benefit to them. Only where it could be said that there would be no benefit accruing to an unborn child from the variation should the court not give its consent.

On the other hand, even if it can be shown that a proposed variation will benefit one particular beneficiary under the trust, it is not always the case that the court will order the variation to take place if the proposal is not for the benefit of other beneficiaries. This was shown in Re Steed’s Will Trusts.45

Joshua Steed declared two trusts in favour of his sister, Gladys, in his will in which he left a farm with approximately 50 acres of land and £4,000 for her life with remainder to whoever she might appoint either in her lifetime or by her will. Joshua made it clear that the trust was to be of a protective nature in that whilst Gladys could be entitled to the capital in the farm, the trustees had to bear in mind that they had to retain sufficient funds to support her during her life. Joshua was concerned that one of their brothers would seek, to paraphrase Lord Evershed MR, to ‘sponge’46 off Gladys if she was given the property absolutely.

After Joshua’s death, the trustees wanted to sell the farm. They were concerned that the farm would cost too much to keep in good repair. Gladys, however, instituted proceedings to restrain them from selling the farm. She also put forward an application to vary the trust under the 1958 Act.

Her proposal was that she should be entitled to the farm absolutely. She sought to appoint herself as the remainder beneficiary and her arrangement under the Act was for the court to recognise and sanction that appointment. The trustees resisted the proposal.

The court’s approval to the arrangement was needed before it could go ahead. Gladys came within s 1(1)(d) of the Act, being entitled to the trust property under a protective trust. In addition, the language of the trust created by Joshua was of a discretionary nature which could include a future husband that Gladys might marry. In theory, she could have married and appointed her future husband as the remainder beneficiary under Joshua’s trust. The potential of this occurring meant that the court would also need to give its consent to the variation under s 1(1)(b) of the Act.

Lord Evershed MR believed that the court could not just consider the arrangement from Gladys’ point of view, even though she was the only beneficiary in existence at the present time. The court also had to consider the position from the point of view of all potential beneficiaries which, on the facts, would include any future husband that she might marry. In deciding whether to give its consent on behalf of a person who could not give their own consent, the court had ‘to look at the scheme as a whole and, when it does so, to consider, as surely it must, what really was the intention of the benefactor.’47

Upjohn LJ put the court’s duty under the Act in a similar way:

this court is not confined to the narrow duty of inquiring into the effect of a proposed scheme upon those on whose behalf approval by the court is sought. The court must be satisfied that the scheme, looked at as a whole, is proper to be sanctioned by the court.48

The court could not, in this case, blindly follow Gladys’ wishes. The court had to take a wider view of the proposal and give or withhold its consent on behalf of those people who could not give their own consent under the 1958 Act. In doing this, the court would take into account the wishes of the proposer of the arrangement, together with the wishes of the trustees but ultimately the court would revert to the reasons why the settlor established the original trust. Here Joshua was concerned that Gladys would feel pressurised by another individual to divest herself of some of the money under the trust if she was entitled to it absolutely. Such a consequence had to be resisted, even if Gladys herself felt that a variation of the trust in this manner was to her own personal benefit. It was not her benefit that was in issue (as s 1(1)(d) prevented the court from assessing whether the variation was to her benefit or not) but the potential benefit to a future husband.

Re Steed’s Will Trusts was distinguished by the Court of Appeal in Goulding v James49 where it was held that the testator’s intentions were not to have great weight applied to them when the court decided whether to permit the variation to go ahead. Here Violet Froud created a trust in her will, leaving a life interest in her residuary estate to her daughter, June with remainder to her grandson, Marcus, provided Marcus reached 40 years old. After Violet’s death, June and Marcus wished to vary the trust, giving them both a 45 per cent share in the absolute interest in the residuary estate with the final 10 per cent share to be left to Marcus’s children. The application to vary the trust was made under s 1(1)(c) of the Act on behalf of Marcus’s future children.

Unusually, at first instance, Laddie J refused to sanction the variation. Relying on Re Steed’s Will Trusts, he took into account Violet’s wishes when setting up the original trust. Violet had only given June a life interest in the trust property because she did not trust her son-in-law. She also thought that Marcus needed time to settle down in life, so chose a fairly old contingency age (40) for him to receive his share.

On appeal, the Court of Appeal approved the proposed variation. Re Steed’s Will Trusts could be distinguished. Re Steed’s Will Trusts concerned an application primarily under s 1(1)(d) where the court had no opportunity to assess whether the variation was for the benefit of the person on whose behalf it consented. The arrangement in the present case was proposed under s 1(1) (c). This meant that the court had to weigh up whether the proposed variation was for the benefit of Marcus’s children or not. The court was specifically charged with this task under the Act. It was not charged with the task of assessing whether the variation was for the settlor’s benefit. As the variation was plainly for the benefit of Marcus’s children, it could go ahead.

Goulding v James shows that the settlor’s intentions therefore carry very little (if any) weight to an application to vary a trust made under s 1(a)–(c). The court approves the variation for the person on whose behalf the application is made and the settlor’s intentions should usually be disregarded. Mummery LJ in GouJding v James made it clear that Re Steed’s Will Trusts was an application under s 1(1) (d) of the Act, where the court could take into account the settlor’s original intentions as it is not directed to assess whether the variation is for the proposed beneficiary’s benefit.

Section 1(11(b)

Section 1(1) (b) was considered specifically in Knocker v Youle50 and given a very narrow interpretation by the High Court.

Charles Knocker established a trust in favour of his daughter, Augusta, for life with remainder to such persons as she should appoint in her will. If she failed to appoint any further beneficiary, the trust fund would pass to her brother. Then, if he failed to choose beneficiaries, the fund would pass to her mother for her life with the remainder interest to her four sisters and their issue. The issue were effectively Augusta’s 17 cousins. Due to the fact that there were so many of them, some of whom lived in Australia, none were made party to the proposed variation to the trust. Instead it was argued that the High Court could vary the trust using its powers under s 1(1)(b) as these were persons who ‘may become entitled’ to an interest in the trust.

Warner J refused to sanction the variation of the trust. He held that the cousins were not people who ‘may become entitled’ to the trust fund. They already enjoyed an interest under the trust, albeit a contingent one. Of course, their interest was subject to neither Augusta nor her brother appointing any other beneficiaries of their share but that did not matter: the legal reality was that the cousins enjoyed an interest in the trust fund and the court had no jurisdiction to consent on their behalf under s 1(1)(b).

The decision in this case is probably right. The court should not be in a position to override the consent required from adults who are sui juris whose consent is simply difficult to obtain.

Perpetuities and variations under the 1958 Act

In Re Holt’s Settlement, Megarry J also dealt with the question of perpetuities in his judgment and answered the question of when the perpetuity period should commence in a variation. Was the perpetuity period to commence from the original declaration of trust or from the time the variation was sanctioned by the court? He believed the period should commence from when the variation was sanctioned by the court as that was when the new ‘instrument’ effecting the variation would take effect. This has the effect that a variation today of, say, a declaration of trust entered into in 2001 would now be able to enjoy an almost certainly longer perpetuity period (of 125 years) than that which the original declaration of trust contained.51

Substance v form under the 1958 Act: the substratum guideline

In Re Holt’s Settlement, Megarry J had no issue with how the variation was effected. He believed that a complete revocation of the current trust and the drafting of a new trust could amount to a variation under the Act. He felt that this was merely a question of form. Varying the trust by a revocation and the drafting of an entirely new trust deed would be as valid as varying the trust by merely altering some of the words in the original trust document.

Whilst equity is not concerned about the form the variation takes it is, of course, concerned to see that the substance of the original trust is not affected by the variation. If the substance of the original trust is affected by the proposed variation, the court will not sanction such a variation to go ahead, as is shown by Re T’s Settlement Trusts.52

The facts concerned a trust being held for two infants. Their interests would vest when they reached 21. The relevant infant was due to reach 21 in November 1963. In June 1963, her mother applied to the court to vary the trust. Her view was that her daughter was ‘alarmingly immature and irresponsible as regards money’53 and would not be able to manage such a large sum. Her proposal was that her daughter’s share should be transferred to new trustees for it to be held on protective trusts.

Wilberforce J refused to consent to the variation as proposed. He thought that he did not have any jurisdiction to do so under the 1958 Act as the proposal went too far beyond a variation and was an entirely new resettlement. In most cases where a proposal was made to vary a trust so close in time to the infant beneficiary reaching adulthood, he would expect the infant’s views to be taken into account so that she could decide for herself whether to consent to such a variation.

The notion that the 1958 Act does not permit a wholly new resettlement to take place but merely a variation of the existing trust was summed up by Megarry J in Re Ball’s Settlement Trusts54 as follows:

If an arrangement changes the whole substratum of the trust, then it may well be that it cannot be regarded merely as varying that trust. But if an arrangement, while leaving the substratum, effectuates the purpose of the original trust by other means, it may still be possible to regard that arrangement as merely varying the original trusts, even though the means employed are wholly different and even though the form is completely changed.55

The court, thought Megarry J, should exercise a wide jurisdiction to give consent on behalf of those individuals listed in s 1(1)(a)–(d). The court was merely giving consent which those people could not give and, in that regard, ‘the power of the court to give that assent should be assimilated to the wide powers which the ascertained adults have’.56

The facts concerned a trust which gave a life interest to the settlor and a power for him to appoint the trust fund to each of his two sons or their wives or their children, providing that not more than half of the trust fund could be appointed to either family. The proposed variation was simply to split the trust fund into two equal shares. Each share was to be held on trust for each son for their lives, remainder to their children.

Megarry J approved the proposal. He believed that the substratum of the original trust remained in the variation. The new trusts still gave half of the trust fund to each son and his family. The variation was not being used to take a beneficiary’s interest from them, as occurred in Re T’s Settlement Trusts.

It is essential to understand that a variation of a trust will not be permitted if it changes the fundamental basis, or substratum, of it.

But the cases illustrate that the ‘substratum test’ has been set at a high level. As you have seen, variations of trust have been sanctioned where the beneficial interest vesting in beneficiaries has been delayed and even where some beneficiaries have the potential to lose out from their original entitlement.

Perhaps the underlying rationale of the cases where such variations have been permitted is to enable trustees to retain a certain amount of discretion and room to manoeuvre when administering the trust. So variations have been permitted when administering the trust would otherwise result in adverse taxation consequences which the settlor did not intend. But where proposals overstep the mark in terms of surpassing manoeuvring room and extending into altering the settlor’s original intentions (as to who should benefit, for example) the substratum test would mean that the court would not give its sanction.

Summary of the Variation of Trusts Act 1958

The usual procedure for a proposed variation to occur is for an adult beneficiary to make an application to the High Court for approval to the variation. The key requirements are:

[a] the arrangement has to benefit the person(s) on whose behalf the court is being asked to consent (unless the person comes within s 1(1)(d)). ‘Benefit’ under the Act may be financial but the court will consider the matter in the round, taking into account social and moral factors too. In reality, the court looks at the whole proposal to decide if there is a benefit for the beneficiary on whose behalf the court is being asked to consent, weighing up the advantages and disadvantages of the proposal; and

[b] the underlying basis of the trust — the substratum — must not be affected by the proposed variation.

The Variation of Trusts Act 1958 is the main statutory source that allows for the most wide-ranging variations and revocations of trust to occur. The following statutes permit trusts to be varied but only in specific circumstances.

Trustee Act 1925, s 57

Section 57 of the Trustee Act 1925 permits trustees or beneficiaries57 to seek the court’s consent to vary a trust by granting the trustees a power either to acquire or dispose of trust property. Its enactment was intended to supplement the ‘emergency’ inherent jurisdiction of the court to vary a trust if the court did not believe that an emergency (as defined under its inherent jurisdiction) had arisen.

The step-by-step requirements of s 57 were given by Evershed MR in Re Downshire Settled Estates:58

the section envisages, on analysis: (i) an act unauthorized by a trust instrument, (ii) to be effected by the trustees thereof, (iii) in the management or administration of trust property, (iv) which the court will empower them to perform, (v) if in its opinion the act is expedient.59

The purpose behind s 57 is to widen trustees’ powers of management or administration when such a power has not been included in the original trust instrument by the settlor. ‘Management or administration’ means ‘the managerial supervision and control of trust property on behalf of beneficiaries’.60 The reference in the section to ‘management or administration’ does not allow the court to grant the trustees a power to alter the extent of beneficial interests under the trust.

The court may grant the power subject to such terms as it thinks fit and may direct how costs be paid as between the capital and income of the trust. ‘Expedient’ in the legislation means that the power requested must be in the interests of the trust as a whole.

Section 57 was recently considered in NBPF Pension Trustees Ltd vWarnock-Smith,61 where the High Court concluded that the ability of the court to grant the trustees a power under the section could not be used if it would affect the substance of the beneficial interests under the trust.

Key Learning Point

The Variation of Trusts Act 1958 is much wider in scope than s 57 of the Trustee Act 1925. The 1958 Act enables much more fundamental variations to the trust to occur such as varying the beneficial entitlements under the original trust, as occurred in Re Holt’s Settlement. Section 57 of the Trustee Act 1925 is designed to be used to grant trustees power to making administrative changes to the trust.

The facts concerned the distribution of surplus money in two pension schemes. The trustees had over £350 million to distribute to members of the schemes. Most of the money was distributed, but the trustees had been obliged to set up reserve funds for beneficiaries they could not successfully trace. The original idea was that if any untraced beneficiaries came forward at a later stage, they would be paid the amounts due to them from the reserve funds. Approximately £22 million remained in the reserve funds and five years after establishing the reserve funds, the trustees wanted to wind the schemes up completely and distribute the money held in the reserve funds. The matter fell within s 57 due to taxation reasons: in distributing the money, the trustees would have been making taxable payments and such payments were not allowed on the terms of the original schemes. The trustees thus needed to be granted a power of management or administration to distribute the trust property that had not been granted to them when the original schemes were established.

Floyd J recognised the court’s ability to grant a power of management or administration of the trust property to the trustees ‘but not where it would affect the substance of the beneficial trusts themselves’.62 On the facts, however, he believed that a power could be granted to the trustees to make the taxable payments they desired and to wind up the schemes. He thought the powers desired were ‘practical ones aimed at getting some money to particular classes of recipient who are otherwise fully entitled to receive benefits under the scheme’.63 The trustees sought only a specific and not a general power to achieve that aim. The power sought was ‘merely a variation in the mechanism for getting that money to its intended recipient, and does not disturb the underlying interests [of the trust]’.64

The trustees also wanted the ability to purchase an insurance policy to protect them from claims for breaching their duty as trustees, perhaps, for example, for wrongly paying beneficiaries who were not entitled to benefit from the schemes or for not paying those who were actually entitled. Floyd J held that the purchase of such insurance was probably within the terms of the schemes as drafted but if he was wrong about that, he authorised it under s 57.

In granting this power, he emphasised that powers granted by the court under s 57 had to be for the benefit, not just of the trustees but for the trust as a whole.

Emphasis had been placed on the trust as a whole benefiting in the earlier case of Re Craven’s Estate, Lloyd’s Bank Ltd v Cockburn (No. 2),65 where Farwell J had said:

the word ‘expedient’ quite clearly must mean expedient for the trust as a whole. It cannot mean that however expedient it may be for one beneficiary if it is inexpedient from a broad view of other beneficiaries concerned the court ought to sanction the transaction. In order that the matter may be one which is in the opinion of the court expedient, it must be expedient for the trust as a whole.66

In Re Earl of Strafford, Dec’d, Royal Bank of Scotland Ltd v Byng,67 Buckley LJ emphasised that, when considering the interests of the beneficiaries, the court must balance their competing interests between them in as fair a manner as possible:

‘Expedient for the trust as a whole’ must mean, it seems to me, the same as ‘expedient in the interests of all beneficiaries under the trust’, provided that it be kept in mind that in considering the interests of the beneficiaries collectively, trustees must take into account the effect of what is proposed upon the several individual interests of the beneficiaries and hold the scale fairly between them.68

In NBPF Pension Trustees Ltd, Floyd J held that the entire trusts would benefit from an insurance policy as it would meet any claims for breach of duty instead of the trust fund itself.

It was not, however, for the benefit of the trust as a whole to purchase a second type of insurance policy to meet claims of any unknown beneficiaries coming forward. Such indi-viduals were excluded from the terms of the schemes in any event and hence could have no grounds for bringing any claim. An insurance policy to guard against any claims would be superfluous and, consequently, a waste of the trust fund’s assets in purchasing such a policy.

Section 57 cannot be used if to do so would change the beneficial interests under the trust. An application under s 57 may be successful, however, if it can be shown that changing the beneficial interests is an incidental consequence of the granting of the additional adminis-trative power, as was shown in Southgate v Sutton.69

The facts concerned an application to divide a trust fund into two parts: one part was to be for beneficiaries in the United Kingdom and the other was to be held on trust for beneficiaries in the United States of America (known as the ‘Southgate beneficiaries’). There was no express provision in the trust instrument permitting the trust to be divided in such a manner. An application was made to the court requesting such a power be granted to the trustees to do so under s 57. At first instance, Mann J refused the application. He felt that allowing the application would change the beneficial interests in the trust as the beneficiaries would be divided into two distinct groups, the Southgate beneficiaries and the UK beneficiaries, with each group being entitled to their own fund.

In giving the judgment of the Court of Appeal, Mummery LJ said70 that the court should take a ‘cautious’ approach to applications made to it under s 57. Yet the application to split the trust into two could be granted under s 57. He did not believe that the purpose of the application was to alter the beneficial interests of the trust. The purpose was to save taxation being paid, primarily in the United States. This was expedient for the trust as a whole. Any impact on the beneficial interests being altered was an incidental consequence of the trust being partitioned. Where this was the case, the additional administrative powers needed for dividing the trust could be granted under s 57.

Trustee Act 1925, s 53

Section 53 of the Trustee Act 1925 contains another bespoke provision enabling the court to vary a trust. The section applies only to infants who are beneficiaries under a trust. The court is given the ability to appoint a person to sell trust property or sell shares or receive dividends from shares for the ‘maintenance, education or benefit’ of the infant beneficiary.

Essentially, the aim of s 53 is to grant a power to raise money for the infant beneficiary’s benefit by appointing an individual either to sell trust property or secure income from shares owned by the trust.

It is doubtful whether many modern-day applications are made to the court under s 53 given the usual wide powers drafted expressly in modern trust deeds which were not available when s 53 was originally enacted.

Inheritance (Provision for Family and Dependants) Act 1975

The Inheritance (Provision for Family and Dependants) Act 1975 gives certain categories of individual a right to claim against the estate of a deceased person if it can be shown that the claimant was maintained by the deceased immediately prior to their death and that the will and/or law of intestacy fails to make ‘reasonable financial provision’71 for the claimant.

Section 2(1)(f) of the Act specifically enables the court to make an order varying a partic-ular type of trust in the claimant’s favour. The type of trust that the court may vary is a marriage settlement (a trust made at the time two individuals get married) made in favour of the deceased or the deceased and his spouse.

To benefit from a variation of the trust in their favour, the claimant must be:

[a] the surviving spouse;

[b] a child of the marriage; or

[c] a person who was treated as a child of the marriage by the deceased.

If the claimant is successful, the court may vary the marriage settlement of the deceased in order to provide reasonable financial provision for the claimant.

Setting a Trust Aside

The previous part of this chapter considered how an existing trust might be varied. A more fundamental question must now be addressed: When can an otherwise perfectly formed trust be set aside? Initially, this may appear to be an odd thought: If a settlor has correctly declared a trust and constituted it, why should it be set aside at all? The main reason is bound up in public policy, as the facts of Re Butterworth72 demonstrate.

Charles Butterworth was a baker who owned his own business in Manchester. He owned several houses. In 1878, he entered into a trust in which he placed the houses and some of his other property on trust with his wife and children as beneficiaries. At the same time as declaring the trust, he decided to expand his business by purchasing a grocer’s business. He owned the grocery business for only eight months when he sold it, not having managed to make a profit from it. He sold the business for the same price as he had bought it. Just over two years later, he filed a petition for bankruptcy. His trustee in bankruptcy sought to have access to the houses that had been placed on trust for Charles’ wife and children. He wanted the trust declared to be non-binding on him as being able to sell the houses would raise a large amount of money which could be used to pay Charles’ creditors.

Glossary: Trustee in bankruptcy

A trustee in bankruptcy’s main task is to administer a bankrupt’s estate to settle the debts of their creditors. This type of trustee is akin to a personal representative of a deceased individual in that they gather in as many assets as possible, realise their value and then distribute the fund to the creditors.

Charles sought to hide behind the declaration of trust. His argument was that he was not bankrupt at the time he made the declaration of trust, therefore it ought to stand. That would mean that his wife and children would own the equitable interests in the houses and he, of course, would still be able to continue living in one of the houses with them, whilst his creditors would receive nothing. The difficulty he had was that he was not, in fact, able to pay his debts when he first entered into the declaration of trust.

The Court of Appeal set aside the declaration of trust. Jessel MR said:

a man is not entitled to go into a hazardous business, and immediately before doing so settle all his property voluntarily, the object being this: ‘If I succeed in business, I make a fortune for myself. If I fail, I leave my creditors unpaid. They will bear the loss’.73

The settlor could not have it both ways: he could not place his property into the hands of someone else by using the mechanism of a trust and yet still benefit from that property if his business failed. The trust was essentially a sham:74 there was no real intent to benefit his wife and children; merely instead to put his property beyond his creditors’ reach where he might still enjoy it. The declaration of trust was void although it is probably the case nowadays that such a declaration of trust would be voidable.75

Re Butterworth was not the first decision in the area, but is a useful case for clearly illustrating the policy behind the law. The law in this area has now been enshrined into the Insolvency Act 1986. Two sections of the Act are relevant: ss 339 and 423.

Insolvency Act 1986, s 339

Section 339 of the Insolvency Act 1986 applies to an individual who has (i) entered into a transaction with anyone at an ‘undervalue’ and (ii) within a certain time period. ‘Undervalue’ is defined in s 339(3) as:

[a] making a gift to a recipient or receiving no consideration from the recipient for property given to him;

[b] entering into a transaction with a recipient the consideration for which is marriage or a civil partnership; or

[c] entering into a transaction with a recipient where the consideration given by the recipient is significantly less than the value of the transaction itself.

The relevant time period is generally five years before the petition for bankruptcy is presented. However, transactions entered into between two and five years before the petition for bankruptcy is presented will be immune unless the debtor was insolvent at the time or became insolvent due to entering into the transaction. Being insolvent generally means being unable to pay debts as they fall due.

Suppose Scott owns a house solely by himself and wishes to go into business.

Scott may decide to declare a trust in which he gives the property to his fiancee, for her to hold on trust for both of them. The consideration may be the parties’ forthcoming marriage.

Such a trust would be liable to be set aside by Scott’s trustee in bankruptcy if Scott was to receive a petition for his bankruptcy within two years of declaring the trust. The marriage cannot be good consideration for the transaction. Effectively, Scott is divesting himself of a valuable asset which could have been used to pay his creditors if he goes bankrupt.

The declaration of trust would be valid after two years had passed since it was entered into unless Scott was either insolvent at the time he declared the trust or became insolvent as a result of it.

The ‘long-stop’ date under s 339 is five years, after which all transactions entered into at an undervalue are immune from being attacked, even if Scott was insolvent at the time of the transaction or it caused his insolvency.

If a transaction has been entered into at an undervalue within the relevant time period, the trustee in bankruptcy can apply to the court to make an order under s 339(2) to restore ‘the position to what it would have been if that individual had not entered into that transaction’. Effectively, this means that any declaration of trust may be set aside so that the individual once again owns the property that he tried to divest himself of in the declaration of trust. The prop-erty would then become part of the bankrupt’s assets which the trustee would seek for himself. Alternatively, under s 342(1)(a), the court may order the property to be transferred directly to the trustee in bankruptcy.

Insolvency Act 1986, s 423

To bring a successful action under s 339 of the Insolvency Act 1986, the trustee in bankruptcy must show that the bankrupt either was insolvent at the time he entered into the relevant transaction at an undervalue, or became insolvent as a consequence of it. There is no requirement that dishonesty has to be found on the bankrupt’s part (for example, he may have been following the advice of a professional).

Section 423 again applies where an individual enters into a transaction at an undervalue as defined in s 339. The court may, once again, make an order restoring the individual to his pre-undervalue transaction. Under this section, however, the court can only make such an order one if either requirements of s 423(3) are satisfied. They are that:

[a] the transaction was entered into specifically to put assets beyond the reach of a creditor who was making or had the possibility of making a claim against the individual; or

[b] the court is satisfied that the interests of a creditor were prejudiced by the transaction at an undervalue being entered into.

Section 424 sets out who may bring an action under s 423. If the debtor has already been adjudged bankrupt or is a company in the process of being wound up, the trustee in bank-ruptcy or liquidator respectively may apply to the court. Only with the court’s permission may a victim of the debtor bring an action. In any other case, s 424 (1)(c) provides that it is only a victim of the debtor who can bring a claim.

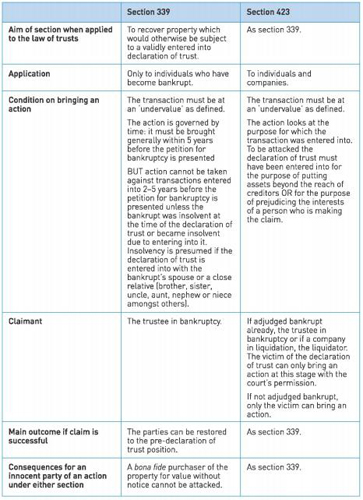

Taken together, the provisions of ss 339 and 423 provide useful tools to ensure that trustees in bankruptcy may set aside declarations of trust if the declaration has been entered into essentially for an illegal reason: to place the individual’s assets beyond the reach of his creditors. A comparison table highlighting key differences between the two sections can be found at Figure 10.2.

Points to Review

You have seen:

![]() the general rule is that a trust, if properly formed, is sacrosanct and will not be varied or altered by the court;

the general rule is that a trust, if properly formed, is sacrosanct and will not be varied or altered by the court;

![]() a trust can be varied but only in exceptional circumstances by the court’s inherent jurisdiction and in particular circumstances by various statutes. The Variation of Trusts Act 1958 is of the most general application but that only applies where the court is consenting because a particular type of beneficiary under the trust cannot give their own consent; and

a trust can be varied but only in exceptional circumstances by the court’s inherent jurisdiction and in particular circumstances by various statutes. The Variation of Trusts Act 1958 is of the most general application but that only applies where the court is consenting because a particular type of beneficiary under the trust cannot give their own consent; and

![]() that a trust can be set aside if it has been entered into for an illegal reason, such as to put the individual’s assets beyond the reach of his creditors. Specific sections of the Insolvency Act 1986 have codified the ability of a trustee in bankruptcy to have access to the individual’s property that they believed they were securing by means of a trust.

that a trust can be set aside if it has been entered into for an illegal reason, such as to put the individual’s assets beyond the reach of his creditors. Specific sections of the Insolvency Act 1986 have codified the ability of a trustee in bankruptcy to have access to the individual’s property that they believed they were securing by means of a trust.

Making connections

Making connections

Varying and setting aside a trust are essentially two stand-alone topics that are necessary for you to understand if you are to gain a rounded knowledge and appreciation of how trusts operate in practice, as well as in theory.

Useful Things to Read

Useful Things to Read

The best reading is contained in the primary sources listed below. It is always good to consider the decisions of the courts themselves as this will lead to a deeper understanding of the issues involved. A few secondary sources are also listed, which you may wish to read to gain additional insights into the areas considered in this chapter.

Primary sources

Chapman v Chapman [1954] AC 429.

Re Holt’s Settlement [1967] 1 Ch 100.

Re Steed’s Will Trusts [1960] Ch 407.

Re Weston’s Settlements [1969] 1 Ch 223.

Re Windeatt’s Will Trusts [1969] 1 WLR 692.

Southgate v Sutton [2011] EWCA Civ 637.

Insolvency Act 1986, ss 339 and 423.

Trustee Act 1925, ss 53 and 57.

Variation of Trusts Act 1958.

Secondary sources

Robert Blower, ‘The limits of section 57 Trustee Act 1925 after Sutton v England’ (2012) T & T 18(1), 11–16 (note). This article examines the decision of the Court of Appeal in Southgate v Sutton.

Alastair Hudson, Equity & Trusts (7th edn, Routledge-Cavendish, 2012) ch 10.