Chapter 11

Secret Trusts, Half-Secret Trusts and Mutual Wills

Chapter Contents

Secret Trusts and Half-Secret Trusts

In this chapter, you consider the topic of secret trusts and the related area of mutual wills. The connecting link between the two topics is that the details of both are based on an agreement which is not necessarily apparent from the documentation. Secret trusts are so called because a testator has made a secret agreement with a trustee that they will hold property on trust for an undisclosed beneficiary after the testator’s death. Mutual wills are where two people make identical wills and each binds the other to the same undisclosed agreement where their property will go after their deaths.

As You Read

Look out for the following key points:

![]() the definition of a secret trust, a half-secret trust and how they differ from each other;

the definition of a secret trust, a half-secret trust and how they differ from each other;

![]() the rationale underpinning the court’s enforcement of secret and half-secret trusts; and

the rationale underpinning the court’s enforcement of secret and half-secret trusts; and

![]() the concept of mutual wills and the notion that they are based on an agreement formed between the testators that the survivor should not alter their will after the first one of them has died.

the concept of mutual wills and the notion that they are based on an agreement formed between the testators that the survivor should not alter their will after the first one of them has died.

Secret Trusts and Half-Secret Trusts

Definition

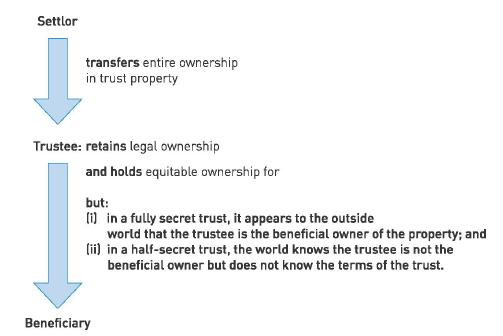

A secret trust is a trust of which there is, prima facie, no evidence of its existence in a testator’s will. The secret trust is probably an example of an express trust although there is debate (both judicial and academic) about whether it might be a constructive trust. It appears, on a reading of the relevant clause in the will, that property has simply been given to the recipient and that they are both the legal and beneficial owner of it. Unbeknown to readers of the will, however, the recipient is not the beneficial owner of it. Instead, he will have been asked by the testator (obviously before the testator’s death) to hold the property on trust for the real beneficiary. In that manner, a trust will be formed of the property after the testator dies. The recipient will own the legal title and the ‘real’ beneficiary will enjoy the equitable interest. A trust will have been formed by the testator but its existence will be kept secret from the world at large. Sometimes these trusts are known as ‘fully’ secret trusts, in part to differentiate them from ‘half’-secret trusts.

A half-secret trust is similar to a fully secret trust. The difference is that whilst there is absolutely no clue in the testator’s will that a fully secret trust has been formed, there is a giveaway that the testator has declared a half-secret trust. A half-secret trust gives an indication that the property is subject to a trust by using the words ‘on trust’ or similar. What remains secret are the terms of the trust. Consequently, a reader of a will where a half-secret trust has been declared knows that the recipient is a trustee but does not know who the true beneficiary is or any other terms of the trust.

Both types of secret trust are illustrated using the now-familiar diagram in Figure 11.1.

Background: Scandal in the law of trusts!

Fully and half-secret trusts appear in wills. Section 9 of the Wills Act 1837 provides that no will can be valid unless it is in writing, signed by the testator and witnessed by at least two witnesses present at the same time.1 After the testator has died, the will usually becomes a

public document, which any member of the public may inspect. This means that the contents of a testator’s will become available for the world at large to read.

As will become clear, a number of the early cases on secret trusts revolved around a testator wishing to make provision in his will for his mistress and/or illegitimate offspring. Leaving property as a gift or declaring a trust in the will would have meant that the testator’s wife and family would have immediately become aware of the existence of the testator’s mistress and illegitimate children. Thus testators began to use the mechanism of a secret trust to conceal the true beneficiary of their generosity in their will. The testator would commonly provide the detail of the trust in a separate document to their will or even sometimes in oral instructions to the trustee. The latter is sometimes referred to as ‘parol evidence’.

The difficulty with the terms of secret trusts being contained in parol evidence is, however, that they run contrary to the principle of transparency and openness enshrined in s 9 of the Wills Act 1837 that all terms of a will should be in writing and that the will usually becomes a document available to the public for their inspection after the testator’s death. It is this conflict that the courts have wrestled with from the nineteenth century when wills containing secret trusts first became prevalent.2

Fully Secret Trusts

Requirements

The requirements for the validity of a fully secret trust were set out by Brightman J in Ottaway v Norman.3 He said that it must be shown that:

[a]the testator intended to impose an obligation on the recipient of the property that the recipient should hold the property on trust for the ‘true’ beneficiary;

[b]the testator communicated that intention to the recipient; and

[c]the recipient accepted the testator’s intention. The recipient’s acceptance of that obligation could be either express or implied by acquiescence.

First requirement: An intention to impose an obligation on the recipient that the property should be held on trust for the true beneficiary

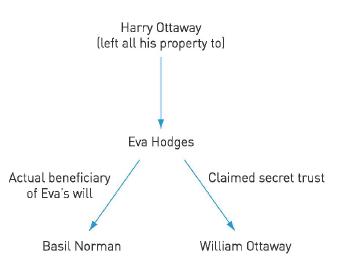

The facts of Ottaway v Norman showed that all three requirements for a valid trust were met. The facts are summarised in Figure 11.2.

Harry Ottaway wrote his will in 1960, in which he left his bungalow in Cambridgeshire together with its contents to his partner, Miss Eva Hodges, with whom he had lived for nearly 30 years. Harry died in 1963. Eva died five years later, having left the bungalow and the contents to the defendant, Mr Basil Norman. Harry’s son, William Ottaway, brought an action claiming a declaration that the house and its contents were rightfully his. The legal basis of his action was that his father had told Eva on a number of occasions that he wanted the bungalow and its contents to go to William on her death. Eva was to have the property for her life but thereafter it should go to William. William said that Eva had accepted this obligation by never disagreeing with Harry’s intention. Eva’s first will had indeed contained a provision leaving the bungalow and its contents to William. She made a later will in 1967, however, leaving the bungalow and the contents to Basil. The difficulty for William (as with all claimants alleging the existence of a secret trust) was that it appeared on the face of Eva’s will that Basil was the true and rightful recipient of the bungalow and its contents. William’s action was, therefore, based on the existence of a secret trust founded on the conversations between Harry and Eva.

Having heard the evidence, Brightman J found that Harry had established a secret trust in William’s favour. Harry had intended that Eva give the bungalow and its contents to William after her death, he had communicated that intention to her and that she had accepted that intention.

Brightman J also made other important points concerning secret trusts:

[a] he felt that it made no difference to the existence of a secret trust as to how the recipient was to carry out the testator’s wish. In other words, it did not matter whether the recipient was to carry out the trust through leaving property by will to the true beneficiary, as was Harry’s intention here, or if the property was to be left to the true beneficiary by means of an inter vivos gift; and

[b] it was not necessary for the establishment of a fully secret trust to show that the recipient had been guilty of committing a deliberate wrong in denying the existence of the trust. There was no evidence that Eva had purposefully sought to defraud William of his entitlement. She simply made an alternate will due to a friendship she had formed with Basil after Harry’s death.

William’s second claim for money which his father had left Eva, allegedly for her use during her lifetime and thereafter for William, failed. Brightman J was prepared to accept, without deciding as such, that in theory a secret trust could be created of property for the recipient to use during her lifetime with remainder of it being left to the true beneficiary. He thought that such a trust would be suspensory in effect during the recipient’s life and would activate itself on her death. But such a trust could not be established on the evidence. It failed the test for certainty of subject matter as it was not clear quite how much money was supposed to be left for William after Eva’s death and to fulfil such certainty, Eva would have had to keep an amount separate from her own money during her lifetime. Such unascertainable amounts infringed the principle of certainty of subject matter and could not create a valid trust. Whilst it is possible to have a secret trust of an asset that would inevitably be wasted by the recipient, the settlor must make the precise subject matter of the trust categorically clear.

Making connections

Remember from Chapter 5 that all express trusts must fulfil the three certainties: of intention, subject matter and object. Certainty of subject matter requires that it must always be clear what the nature and extent of the trust property is. If this is not clear, the trust will fail.

The facts of Ottaway v Norman demonstrated that the testator possessed an intention to subject the recipient to an obligation in favour of the true beneficiary. The other criteria to form a valid trust of communicating that intention to the recipient and the recipient accepting that obligation are no less important. All three criteria must be present for a secret trust to be established.

Ultimately, though, a secret trust is a type of express trust and the requirements needed to form a valid express trust must all be fulfilled. Specifically the three certainties must be satisfied for, as Megarry V-C said in Re Snowden:4

The more uncertain the terms of the obligation, the more likely it is to be a moral obligation rather than a trust: many a moral obligation is far too indefinite to be enforceable as a trust.

This dictum is a salutory reminder that all secret trusts must comply with the necessary ingredients to declare an express trust.

Second requirement: The testator must communicate his intention to the recipient

The testator must clearly place the recipient of their property under a binding obligation to hold that property on trust for the true beneficiary. There must be no doubt that the testator communicates their instructions to the trustee. The controversial issue is when such communication must occur.

It seems not to matter whether the testator communicates his intention to the trustee either before or after he makes his will. This was spelt out by Lord Warrington of Clyffe in Blackwell v Blackwell5 when he said, ‘it is immaterial whether the trust is communicated and accepted before or after the execution of the will’.6

Arguably, it is tidier if the testator can communicate his intention to establish a secret trust with the recipient of that information as trustee before he executes his will. In that way, the testator can be sure, when signing his will, that he has a trustee in place. But it seems that, alternatively, the testator can communicate his intention to create a secret trust after he has executed his will. The reason given by Lord Warrington for this was that, in the worst case scenario, if the testator communicates his intention after he has executed his will and the trustee declines to accept the terms of the trust and administer it, the option always remains open to the testator to write another will, disposing of his property in a different manner or by a secret trust with a different trustee.

What seems to be clear, however, is that the testator must communicate his intention to the trustee during his lifetime and that communication must include the terms of the trust in it. The testator cannot communicate the terms of the trust to the trustee after his (the testator’s) death, as occurred in Re Boyes.7

George Boyes wrote his will in London in June 1880. On the face of the document, he left everything to his solicitor, Mr Carritt, absolutely. George died two years later, in Ghent (Belgium). Mr Carritt’s evidence was that during the writing of the will, George had made it clear to him that he was not to take the property absolutely, but was instead to hold the property on trust, the terms of which George would make clear in a letter which he would send to Mr Carritt when he arrived in Europe. Mr Carritt said that he accepted the trusteeship.

No letter was ever sent to Mr Carritt but after George’s death, two near-identical letters were found in his personal belongings. Both letters said that his property was to be held on trust by Mr Carritt for George’s mistress, Nell Brown. The issue for the High Court was whether this secret trust had been validly declared.

Kay J held that the trust had not been validly declared. There had been no valid communication of its terms — specifically, who the objects of the trust were — during the lifetime of the testator. What the testator had done in writing the two letters was effectively to leave further wills, or codicils (documents which amend part of a will), which did not comply with the requirements of s 9 of the Wills Act 1837. Such a trust could not be allowed to be valid as it would go against the policy of s 9 which required all wills and codicils to be validly witnessed. There was no trust in favour of Nell in the case. Instead, Mr Carritt held George’s property on trust for George’s next-of-kin, as if he had died intestate.

Glossary: Codicil

A codicil is a supplementary document that amends a will. It must comply with the requirements of s 9 of the Wills Act 1837. Codicils were useful in pre-word processor days, as they enabled a testator to amend his will quickly without the need to rewrite the entire will. They are used much less often nowadays as it is often just as quick to amend the will on a computer and reprint the entire document.

Can the terms of the secret trust be constructively communicated by the testator to the trustee?

In Re Keen,8 the issue was whether valid communication had taken place during the testator’s lifetime by a trustee being in possession of an envelope sealed by the testator which contained details of the terms of the trust.

The facts concerned the will of Harry Keen. He wrote his will in 1932, leaving £10,000 on trust to his trustees, on terms which were to be notified by him to his trustees during his lifetime. No mention of the beneficiary’s details were contained in the will. Mr Keen, however, had written a separate memorandum, in which he had set out the details of the beneficiary — a lady whom he knew. He handed the memorandum, which was in a sealed envelope, to one of his trustees. The trustee only opened the envelope after Mr Keen’s death. The issue for the court was whether Mr Keen had successfully created a valid secret trust. (In fact, this was a case concerning a half-secret trust as Mr Keen had made it apparent from his will that the £10,000 was being left on trust.)

Both the High Court and the Court of Appeal held that there was no valid secret trust, but they did so for different reasons.

In the High Court, Farwell J held that Mr Keen had failed to notify the trustees of the intended beneficiary of the trust during his lifetime, as he had promised to do in the clause in his will. Leaving a note which was read only after his death did not constitute notifying the trustees of the beneficiary during his lifetime. No trust of the money could be established. As the trust failed, the money had to fall into Mr Keen’s residuary estate.

In the Court of Appeal, Lord Wright MR thought that Farwell J’s view of Mr Keen’s failure to notify the trustees of the intended beneficiary during his lifetime took a far too narrow view of what ‘notifying’ meant. He said that by holding the beneficiary’s details in a sealed envelope, the trustees had the ‘means of knowledge available [to administer the trust] when it became necessary and proper to open the envelope’.9 He gave a vivid example for which his judgment is famous: ‘[t]o take a parallel, a ship which sails under sealed orders, is sailing under orders though the exact terms are not ascertained by the captain till later.’10

It could not be disputed that the ship sailing under sealed orders had been validly despatched and, in the same manner, the trust could still be successfully administered by the trustee when the time came to do so.

But Mr Keen’s trust still failed. The primary reason was that while he had ‘notified’ the trustee of his chosen beneficiary, the means of his notification contravened s 9 of the Wills Act 1837. The notification by Mr Keen was not correctly drafted according to the requirements of s 9 and neither was it witnessed. He had merely left a letter which, whilst signed by him, had not been witnessed. Mr Keen was not at liberty effectively to reserve to himself a power to circumvent the requirements of s 9, which his letter did.

In addition, any trust which Mr Keen sought to declare had to be consistent with the actual clause in his will in which he promised to declare the trusts. The clause in his will spoke about a notification that he proposed to give to the trustees in the future. In fact, he had prepared the letter well before he had written his will. The details of the beneficiary in the letter, therefore, were not consistent with what he had described in his will.

Communication of the terms of the trust to the trustees can occur either before or after the will is written, but they must be consistent with the precise wording of the will.

Does the testator have to communicate his intention to all of his trustees, or will just some of them suffice? The answers to this question were summarised by Farwell J in Re Stead:11

[b] If the testator makes a fully secret trust by giving property to two trustees to hold as tenants in common but only one promised to hold the property on trust, the other trustee is not bound by the trust and can take their share of the property absolutely; and

[b] If the testator makes a fully secret trust by giving the property to two trustees to hold as joint tenants, whether both trustees are bound by the trust depends on whether the fully secret trust was made in response to a prior promise by the trustees to administer the trust:

If yes, both trustees will be bound to administer the trust; but

If no, only the trustee making the promise is bound to administer the trust. The other trustee may take his share of the property beneficially for himself.

Third requirement: The trustee must accept their obligation to administer the trust

As with any express trust, the trustee must accept their trusteeship. If it cannot be shown that they have accepted their trusteeship, there will be no trust. Acceptance of trustee obligations can be either express or implied. Implied acceptance, according to Lord Westbury in McCormick v Grogan, 12 may be ‘by any mode of action which the disponee knows must give to the testator the impression and belief that he fully assents to the request’.

An example of trustees not accepting their obligations was shown in Wallgrave v Tebbs.13 The facts concerned the will of William Coles who by his will made in 1850, left £12,000 to Messrs Tebbs and Martin together with freehold lands and houses in Chelsea and Kensington, London. The will seemed to leave the property to Messrs Tebbs and Martin absolutely. After Mr Coles‘ death, however, it was claimed that it was not Mr Coles’ intention that they should enjoy the property themselves, but instead that they should hold it on trust for charitable purposes. Their reply to that was they had never had any such communication with Mr Coles. They said that they had understood from Mr Coles‘ solicitor who prepared the will that he had left them the property because he knew one of them personally and the other by reputation as being interested in religious and charitable causes. Mr Coles simply presumed that if he left them money they would use it for such purposes. In addition, Mr Coles had set out his thoughts on this basis in a letter written by Mr Coles’ solicitor to Messrs Tebbs and Martin but Mr Coles had never signed it.

They said that they were sympathetic to Mr Coles‘ wishes but denied that there was a formal trust of the property in existence for such purposes. Their view was that Mr Coles had not communicated his views to them before his death and they had not accepted the alleged trust.

The Vice-Chancellor, Sir W Page Wood, accepted that Messrs Tebbs and Martin knew nothing about Mr Coles‘ wishes until after his death. No communication of the terms of the trust had occurred by Mr Coles and no acceptance of that trust had similarly taken place. Both ingredients were needed if a trust was to be found. No trust was established and Messrs Tebbs and Martin took the property for themselves absolutely.

This decision must surely be right because the office of trusteeship is onerous. It is not equitable if it is enforced upon someone who has known nothing about the prospect of becoming a trustee until after the testator’s death, when it is too late to object to it. A trustee must agree to their role voluntarily. Messrs Tebbs and Martin were denied that opportunity and it was right that no trust was created.

Can the property be increased in a secret trust?

This issue was addressed by the Court of Appeal in Re Colin Cooper.14 Colin Cooper wrote a will, leaving £5,000 on a half-secret trust. His trustees accepted the trust. He then went on a big-game shooting holiday to South Africa, but contracted a fatal illness. Shortly before his death, he wrote another will, puporting to increase the amount left on trust to £10,000. His trustees did not know about this increase, so were never given the chance to accept their new obligation.

The Court of Appeal held that the increase was void. The key ingredients for a valid secret trust of communication to the trustees and agreement by them to administer the trust were only made in relation to the initial £5,000. The trustees had only ever been given the chance of agreeing to administer a trust for £5,000. A trust for double the sum needed their consent.

Sir Wilfred Green MR, obiter, thought that no consent from the trustees would be needed if:

[a] the testator increased the sum to be left on trust by such a small amount (‘de minimis’) that the increase would really make no difference to the trustees administering the trust; or

[b] if the testator in fact left a lower amount to the trustees to administer than he had set out in his trust. Their consent to the greater amount would, by definition, mean that they had agreed to administer a trust up to that sum.

Although the decision concerned a half-secret trust, the judgment of the Court of Appeal was not limited to these types of secret trust and so can apply equally to fully secret trusts.

The rationale underpinning why secret trusts are enforced: Fraud vs the ‘dehors’ the will theories

The cases thus far have shown a desire by testators to set up a trust by using a separate document to convey its terms to the trustees. Sometimes the testator might instead wish to communicate the terms of the trust to the trustees orally as opposed to in writing. But whether the communication is oral or written, the difficulty is the same: unless there is a written document, signed by the testator and duly witnessed by at least two witnesses, s 9 of the Wills Act 1837 will not have have been fulfilled. The prima facie conclusion from this is that any trust which is set out by the testator orally or in a document which does not comply with s 9 is that it cannot be valid. And yet, as has been shown in Ottaway v Norman, such trusts are valid. The reason why equity will recognise such a trust was first explained by the House of Lords in McCormick v Grogan.15

The facts concerned the will of Abraham Craig. He contracted cholera and, on his death-bed, sent for his friend, Mr Grogan, the defendant. He explained to Mr Grogan that he had left all of his property to him. Mr Grogan was to find his will in a desk with a letter with it. Mr Craig never asked for agreement from Mr Grogan to the letter or its contents.

After Mr Craig’s death, Mr Grogan found the will and the letter. The letter contained a long list of friends and relatives to whom Mr Craig wanted his money to be left. It contained the following words towards the end:

I do not wish you to act strictly as to the foregoing instructions, but leave it entirely to your own good judgment to do as you think I would if living, and as the parties are deserving, and as it is not my wish that you should say anything about this document there cannot be any fault found with you by any of the parties should you not act in strict accordance with it.

Mr Grogan made a number of payments to some of the individuals named in the letter. But he declined to make a payment to others, one of whom was the claimant in the case. James McCormick brought an action claiming that Mr Craig had established a trust in his letter and that, as such, Mr Grogan was obliged to pay him the £10 per year for the rest of his life that Mr Craig had awarded him.

The Irish court of first instance declared that the letter did give rise to a trust binding on Mr Grogan. The Court of Appeal in Chancery in Ireland reversed that decision. Mr McCormick appealed to the House of Lords. The House of Lords held that there was no trust on the facts of the case. All Mr Craig had done was to leave a guide for Mr Grogan as to what he should do with the property. The very words used by Mr Craig, giving Mr Grogan freedom and discretion over the choice of the ultimate recipients of the property, showed that he was not imposing any form of obligation on Mr Grogan to distribute the property to particular individuals or a class of them.

What is interesting, though, is that the House of Lords discussed the rationale underpin-ning secret trusts. Lord Westbury explained that a court of equity would enforce a secret trust due to the maxim that equity would not allow a statute to be used as an instrument of fraud. If a trustee denied that a trust existed simply because the testator had not complied with the requirements of s 9 of the Wills Act 1837, equity would intervene to recognise the trust.

Making connections

The rationale underpinning the recognition of secret trusts as explained in McCormick v Grogan is the maxim that equity will not allow a statute to be used as an instrument of fraud. An executor cannot, therefore, hide behind the Wills Act 1837 and refuse to recognise a secret trust, that he voluntarily accepted to administer, before the testator died. Such a response would be to rely on the strict letter of the Wills Act 1837 to the detriment of the testator’s true intentions for their property. Equity will not permit this to occur.

This maxim also underpins equity’s recognition of an oral declaration of a trust of land which is prima facie contrary to the requirements of s 53(1)(b) of the Law of Property Act 1925, as shown in Rouchefoucauld v Boustead.16 See Chapter 4 where this topic is discussed.

However, to intervene, equity had to be absolutely certain that the trustee was committing a fraud. A ‘malus animus’ (bad mind) had to be proved ‘by the clearest and most indisputable evidence’.17 No presumption of fraud could be led but only direct evidence of fraud on the part of the trustee would be accepted by the court. This fraud would have to be that the trustee ‘knew that the testator … was beguiled and deceived by his conduct’.18

If such fraud could be proven, the court would recognise the secret trust, even though its terms were not set out in a document that would comply with s 9 of the Wills Act 1837. Equity would impose a trust on the conscience of the trustee to ensure that they administered the trust that they had agreed to administer. The constructive trust would be the vehicle used for achieving the testator’s true intentions.

In recognising the secret trust, equity was not, according to Lord Westbury, setting aside an Act of Parliament. Instead, it super-imposed upon the person who was appointed an executor under that Act an additional ‘personal obligation, because he applies the Act as an instrument for accomplishing a fraud’.19

On the facts, there was no evidence that Mr Grogan had committed a fraud. He was merely attempting to do his best to administer the property left to him by his friend.

If, however, equity recognises a secret trust due to its maxim that it will not permit a statute to be used as an instrument of fraud, the logical question that arises is why it does recognise the very terms of the trust that the testator set out. Surely recognising the secret trust is equity doing far more than it really needs to do. If equity is merely concerned to prevent the Wills Act 1837 from being used as an instrument of fraud, it could achieve that objective by imposing a resulting trust on the trustee, obliging the trustee to hold the property not for his own benefit but on trust for the testator’s estate. It is, at first glance, odd that equity goes further in imposing a constructive trust which gives effect to the very terms of the trust that ultimately circumvent the requirements of an Act of Parliament.

In Re Snowden, Megarry V-C explained that the law had moved on from the justification given by the House of Lords for the existence of secret trusts in McCormick v Grogan. In this way, he supported the dictum of Brightman J in Ottaway v Norman that fraud was not a prerequisite to establish a secret trust. Megarry V-C felt that fraud was relevant to secret trusts in two ways:

[a] fraud explained the historical development of secret trusts as they were recognised originally as a method of preventing fraud from occurring by trustees denying a trust’s existence. But he said that that did not mean that fraud was nowadays an essential prerequisite for a secret trust to exist; and

[b] fraud did indeed occur on the facts of some cases.

Megarry V-C explained Lord Westbury’s words that equity would need absolutely categorical evidence of fraud existing before intervening to recognise a secret trust. He said Lord Westbury had only intended such high evidence to be needed where the trustee was indeed acting fraudulently. If the trustee was not acting fraudulently, then such a high standard of proof was not needed against him. All that was needed was the normal, civil standard of proof which was that the secret trust had to be proved on the balance of probabilities. It was on those alleging that a secret trust had been created that the burden of proof lay.

There was, in fact, no evidence of fraud occurring on the facts of Re Snowden. There, Ethel Snowden made her will in January 1973, six days before her death. She left everything to her brother. The evidence was that she had entrusted him to deal with the property for her after her death. Surviving her were a number of her relatives, some of whom claimed that she had established a secret trust in her oral instructions to her brother.

In reaching a conclusion that there was no secret trust imposed upon her brother, Megarry V-C quoted with approval comments from Christian LJ in the Court of Appeal in Ireland in McCormick v Grogan20 that:

The real question is, what did he [the testator] intend should be the sanction? Was it to be the authority of a court of justice, or the conscience of the devisee?

It was only if the sanction was a court of law that a trust would be imposed.

In Megarry V-C’s view, all the testatrix intended on the facts was that her brother’s conscience should guide him as to what he should do with her property. She never intended him to face any sanction from a court. No secret trust had been established and, accordingly, the property belonged to her brother absolutely.

Both Ottaway v Norman and Re Snowden decided that no evidence of fraud was needed in the modern world to establish a secret trust. If fraud is alleged, then Lord Westbury’s comments in McCormick v Grogan continue to apply: that clear, indisputable evidence of it is needed. But it seems that fraud, although the historical basis for equity recognising a secret trust, is not needed to establish one in modern times. As such, it must be questioned if it can still be considered to be the underpinning rationale of secret trusts. It seems the more modern justification of a secret trust being recognised — given that fraud is not an essential prerequisite — is that a secret trust is simply an example of an inter vivos trust created by a testator. Provided the testator has fulfilled the requirements as to a valid declaration, the trust is constituted on his death and the trust will be upheld. Fraud seems the historical justification for secret trusts but, in truth, secret trusts are probably no more than examples of normal express trusts nowadays.

The more modern view, therefore, is that the testator actually creates an express trust whilst he is alive. This inter vivos trust is entirely separate from the testator’s will. It is sometimes said to be dehors the will, or outside it. This more modern theory helps explain that the Wills Act 1837 has no application to the trust at all because the trust is not made by the testator’s will but entirely separate to it.

Why does it matter whether the basis of a secret trust is fraud or dehors the will? It only really matters if the subject matter of the secret trust is land. Remember that all trusts of land must be evidenced in writing and signed by someone able to declare the trust.21 If the basis of the trust is fraud, McCormick v Grogan said that equity will enforce the trust by imposing a constructive trust on the trustee. A constructive trust need not be evidenced in writing.22 But if the basis of a secret trust is dehors the will and it is merely an example of equity recognising an express trust, then express trusts of land need to be evidenced in writing (and signed) to be valid under s 53(1)(b) of the Law of Property Act 1925. If a secret trust really is simply an express trust, it seems that equity is overlooking this statutory requirement.

Secret trusts: A modern application

It might be thought that secret trusts are a product of history and of a time when men desired to leave their property to mistresses and children whose existence they wanted to be kept confidential. But a secret trust was claimed to exist in the much more recent case of Davies v The Commissioners for Her Majesty’s Revenue & Customs,23 which illustrates the application of the topic to tax saving.

Mrs Rhona Goodman had died in 2006. Her estate was valued at approximately £164,000. It included the lease of the flat in which she lived together with a portfolio of shares in BP The Inland Revenue claimed that inheritance tax was chargeable on the value of Mrs Goodman’s estate.

Mrs Goodman’s two daughters, who were the executrices and beneficiaries under her will, denied that any inheritance tax was due. They based their argument on a combination of Sched 6, para 2 to the Inheritance Tax Act 1984, ss 5(2) and 22(i)(c) of the Finance Act 1914 and the proviso to s 14 of the Finance Act 1914. In combination, these statutory provisions provided that no tax would be due when one party to a marriage died if its predecessor, estate duty, had been paid when the other party to the marriage died. Mrs Goodman’s husband had died in 1969 and estate duty had indeed been paid on the value of his estate.

To take advantage of this opportunity to save tax, Mrs Goodman’s daughters also had to show that Mrs Goodman’s property was held by her on trust and she did not have the right to dispose of it freely herself. They said that the property left by their father was always held by their mother on a secret trust and they were the residuary beneficiaries of it. The Inland Revenue’s response was that there was never any evidence to support the existence of a trust of their father’s property. They argued that Mrs Goodman was never under any obligation to leave the property that he left to her to their daughters. They also argued that the alleged trust lacked certainty of subject matter, given that it was impossible to say how much of the father’s property had been left on the alleged trust.

The First-Tier Tribunal Judge found that there was no evidence to establish a secret trust. Mrs Goodchild had wished to benefit her daughters on her death but this fell a long way short of her being subject to a binding obligation from her husband to use certain property in particular ways, it being clear that the property then had to be passed on to their children.

Whilst the case suggests that secret trusts are, in theory, not confined to the years of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and instances of men wishing to benefit their mistresses, it is a salutory reminder that there must always be cogent evidence of a secret trust before the court will recognise one. This is, of course, vital in the case of a fully secret trust as it will always contradict the terms of a testator’s will who, at first glance, appears to leave property to the recipient absolutely.

Summary of fully secret trusts

The courts seem wary of recognising secret trusts in the modern environment. The words of Viscount Sumner in Blackwell v Blackwell24 seem as relevant today as when he first delivered them: ‘[i]t is a grave thing to affirm a doctrine that violates the prescriptions of a statute and especially such a statute as the Wills Act.’

It is true that the courts have moved away from basing the doctrine on fraud but the three criteria set out by Brightman J in Ottaway v Norman are still required before a secret trust can be established. The concept of a secret trust is based upon an agreement that was communicated to the trustee and which was accepted by the trustee, either expressly or by conduct, before the testator’s death. Whilst the courts have, in Re Snowden, relaxed the standard of proof required to establish a secret trust to that based on the balance of probabilities, it is suggested that it will always be a difficult task to establish such a trust. This is because the evidence of a secret trust is outside the testator’s will which must remain the best evidence available of the testator’s intentions after his death.

Nowadays, secret trusts are probably examples of inter vivos trusts. As such, if a court is persuaded that one is established, it must comply with all of the requirements needed to declare a valid trust, especially the elements of the three certainties. The theoretical basis of a fully secret trust means that, despite the problem with trusts of land, the dehors the will theory explaining the courts‘ recognition of the trust probably carries more weight than the fraud theory.

Half-Secret Trusts

A fully secret trust is a trust based on an agreement between the testator and the trustee but whose very existence is not revealed in the testator’s will. A half-secret trust is still based on an agreement between the testator and the trustee but there is a clue as to its existence in the testator’s will, for the testator makes it clear that he leaves property to the recipient on trust. The actual terms of the trust are kept secret from wider view.

An example of a half-secret trust has already been discussed in the case of Re Keen, where Mr Keen had made it clear in his will that the £10,000 was being left on trust. His mistress beneficiary’s details were set out in a separate letter which was, of course, separate from the will.

The establishment of a half-secret trust was first recognised by the House of Lords in Blackwell v Blackwell.25

The facts concerned the will of John Blackwell, who left £12,000 on trust in his will to five trustees so that they should use the money ‘for the purposes indicated by me to them’. There was a power to pay over two-thirds of the money ‘to such person or persons indicated by me to them’ but if this occurred, the remaining £4,000 was to be paid to Mr Blackwell’s residuary estate. Mr Blackwell wrote a separate document stating that the ‘person or persons indicated’ were his mistress and his illegitimate son. After his death, his wife and legitimate son brought an action against the trustees, claiming that there was no valid trust of the original £12,000. The House of Lords held that there was a trust and that the separate document could be used as evidence to establish it, despite the fact that it did not comply with s 9 of the Wills Act 1837.

Lord Buckmaster discussed the rationale of fraud underlying a fully secret trust and was of the view that the same rationale could support the existence of a half-secret trust. Preventing the trustee from fraudulently claiming the beneficial interest in the trust property for his own purposes was the reason why a fully secret trust was recognised. The same principle could apply for the recognition of a half-secret trust. If the trustee failed to administer a half-secret trust, the true beneficiary, as well as the testator, would still be defrauded by his actions. Lord Buckmaster almost sought to sum up the rationale underpinning secret trusts as a whole by using language that would today be thought of as being similar to the language of estoppel:26

It is, I think, more accurate to say that a testator having been induced to make a gift on trust in his will in reliance on the clear promise that such trust will be executed in favour of certain named persons, the trustee is not at liberty to suppress the evidence of the trust and thus destroy the whole object of its creation, in fraud of the beneficiaries.27

Viscount Sumner did not see any conflict between the court’s recognition of any secret trust and the requirements of the Wills Act 1837. Equity’s general jurisdiction would act on a trustee’s conscience to ensure that he honoured the terms of the trust. This equitable jurisdiction could run alongside the written will. Equity did not need to concern itself with the majority of wills and only needed to intervene to enforce the trust if the trustee refused to honour it: ‘[equity] makes him do what the will in itself has nothing to do with’.28 Section 9 of the Wills Act 1837 set out merely the form that a will had to take but was silent over how the law of trusts could apply to a trust created in a will. A testator could not, however, reserve to himself a power in his will to set up a trust at some point in the future. Such a provision would fall foul of s 9. A testator could communicate the terms of the trust to the trustee and, provided the trustee accepted that obligation, a secret trust would be established. Such an event would enable the law of trusts to intervene and recognise the trust.

Viscount Sumner was of the view that a half-secret trust should be recognised by equity as much as a fully secret trust:

In both cases the testator’s wishes are incompletely expressed in his will. Why should equity, over a mere matter of words, give effect to them in one case and frustrate them in the other?29

Blackwell v Blackwell was the first case in which it was decided that a half-secret trust could be as valid as a fully secret trust. It also determined for the first time that personal fraud of the trustees was not necessary to establish any secret trust. The trustees in the case were not claiming the beneficial interest in the trust property as their own. Rather, by not recognising the trust, the court would have been sanctioning a fraud on the beneficiaries whom the testator intended to benefit and such fraud would also be on the testator himself.

Requirements

In Blackwell v Blackwell, the House of Lords made no distinction between the requirements for a half-secret trust and those for a fully secret trust: ‘[t]he necessary elements, on which the question turns, are intention, communication and acquiescence.’30

There does, however, appear to be a distinction in terms of timing and when the trustee must have accepted their obligation from the testator. In the case of a fully secret trust, the communication to and acceptance by the trustee of their obligations could occur either before or after the testator made his will. The reasoning behind this was that if the trustee chose not to administer the trust, the testator always had the freedom to write a further will containing different requirements.

It seems that for a half-secret trust to be valid, the trustee must accept his obligations before the testator makes his will. This can be demonstrated by the facts of Re Keen. In that case, Mr Keen had left a letter in a sealed envelope which the trustee only read after Mr Keen’s death. The Court of Appeal held that such action circumvented the requirements of s 9 of the Wills Act 1837, as effectively, Mr Keen was trying to reserve to himself a power to avoid compliance with the statutory formalities in creating a will by leaving an unsigned addendum (addition) to his will.

This same conclusion was reached again in Re Bateman’s Will Trusts31 by the High Court. John Bateman wrote his will in 1924 in which he directed his trustees to pay the income arising from £24,000 to ‘such persons and in such proportions’ as he intended to set out in a sealed letter. After his death, the trustees did act upon a sealed letter written by Mr Bateman. Amongst the issues for the court to decide was whether Mr Bateman had successfully created a valid trust. It would be a half-secret trust as it was clear from the wording of his will that the trustees were not to retain the beneficial interest in the money for themselves but were to pay it to other recipients.

Pennycuick V-C held that the trust was invalid. Following Re Keen, he held that Mr Bateman had referred in his will to a future sealed letter. He had, therefore, attempted to reserve to himself a power to dispose of his property at a future date by an instrument which did not comply with the formalities of s 9 of the Wills Act 1837. Such letter was void and the trust invalid.

Whilst the courts seem united on the premise that it is not possible to create a half-secret trust by reference to a future document, the fact that it is possible to create a fully secret trust by reference to the same type of document is interesting. Perhaps the distinction is down to the concept of the trustee accepting the obligation to administer the trust. In the case of a fully secret trust, if the testator asks the trustee to administer the trust subsequent to writing his will, the trustee still retains complete freedom of choice over whether or not to accept the responsibility. If he declines the obligation, the testator may write a new will. But in the case of a half-secret trust, where the testator states that he will reveal his instructions in a future piece of correspondence, he is effectively obliging the trustee to administer the trust and removing his freedom of choice over whether to be a trustee at all.

Do you think the distinction over future correspondence as to the terms of a trust is merited? Would the law practically be disadvantaged if it was permitted to create half-secret trusts in the same manner as fully secret trusts? And might there be any advantages in simplifying the law in this manner?

Summary of fully and half-secret trusts

The following points can be made:

[a] The successful creation of either a fully or half-secret trust depends on:

[i] intention by the testator to subject the trustee to an obligation to hold property on trust for a beneficiary;

[ii] ‘true’ communication of that intention by the testator to the trustee; and

[iii] acceptance of that obligation by the trustee.

[b] The original theoretical justification for both trusts was fraud. Due to its maxim, equity would not allow the Wills Act 1837 to be used as an instrument of fraud and for the trustee to hide behind it and deny that a trust existed. It seems that that theory has given way nowadays to the dehors theory: that a secret trust is merely an example of an inter vivos express trust, created outside the will. The Wills Act 1837 is thus irrelevant to its creation. However, the requirement of a trust of land needing to be evidenced in writing under s 53(1) (b) of the Law of Property Act 1925 undermines this theory.

[c] If fraud remains the basis of a secret trust, a constructive trust is implied on a trustee to administer the trust. This can work for trusts of land too as a constructive trust of land does not have to be evidenced in writing (by virtue of s 53(2) of the Law of Property Act 1925).

Mutual Wills

As has been seen, a secret trust arises where a testator reaches an agreement with another person that that person will not, as appears from the testator’s will, be entitled beneficially to property seemingly left to him but will instead hold that property on trust for a third-party beneficiary. The terms of the secret trust are outside of the will. The existence of a secret trust depends, however, on an agreement being reached between the testator and the trustee.

The doctrine of mutual wills similarly depends on the notion of agreement. This time, however, the agreement reached is between two people who have agreed between themselves that they will leave their property to each other initially and thereafter to the same beneficiaries. The agreement impliedly confirms that after the death of one, the survivor will honour the agreement by not making a fresh will, distributing their property to other recipients. In consequence of that agreement, they both make wills in identical — or very similar — forms at the same time as each other. If this is the case, the doctrine of mutual wills applies.

Key Learning Point

The consequences of the doctrine of mutual wills applying means that after the first testator’s death, the surviving testator will not be permitted to alter their will under the agreement reached with the first testator. Equity will recognise the agreement reached between both testators and hold that, on the death of the first testator, the survivor becomes bound by a constructive trust and is obliged to hold property on trust for those beneficiaries that the two testators had jointly agreed would benefit.

Requirements

The requirements of mutual wills were set out by Nourse J in Re Cleaver:32

[a] there must be a ‘definite agreement’ between the two testators as to whom they were to leave their property. The agreement had to ‘impose on the donee a legally binding obliga-tion to deal with the property in the particular way’;33

[b] the evidence to establish the agreement must be ‘clear and satisfactory’.34 The standard of proof needed to establish such an agreement was the usual civil standard of on the balance of probabilities an agreement was made;

[c] crucially, relying on the decision of the Privy Council in Gray v Perpetual Trustee Co Ltd,35 it was not enough to show that the two wills were made at the same time as each other and that their terms were similar in order for the doctrine of mutual wills to apply. Those two factors were merely a ‘relevant circumstance to take into account’36 and the ‘whole of the evidence had to be looked at’ to establish if, in fact, the testators intended that they wanted the doctrine of mutual wills to apply to them. The agreement had to be more than the two testators would make wills: it had to be that they would not revoke them.

Nourse J also reviewed the link between secret trusts and mutual wills. His view was that underpinning both doctrines was equity’s willingness to intervene with a constructive trust on the person who denied that a valid agreement existed to deal with property in a particular way. As equity used a trust to enforce an agreement, the certainties of subject matter and of object in particular had to be absolutely settled from the agreement between the two testators. It had to be clear, therefore, what property was being left on trust and who the ultimate beneficiaries were.

The facts of Re Cleaver give a useful illustration of when the doctrine of mutual wills would apply. Arthur Cleaver Sr married Flora Cleaver in 1967. They wrote several near-identical wills, the last one being in 1974. They left everything to each other initially. In Arthur’s will, if Flora did not survive him, he directed that his residuary estate be divided into three equal shares, each share being left to one of his three children from his earlier marriage. Importantly, one of those children, Martha, was only to have a life interest in her share with remainder to the other two children equally. Flora’s will was nearly the same except that if Arthur predeceased her, she left legacies to her two nieces before dividing her estate into the same three parts.

After Arthur’s death, Flora made a new will in 1977. In breach of the agreement she had made with Arthur, she left her residuary estate to Martha and her husband absolutely.

Nourse J held that the doctrine of mutual wills applied to the wills written by Arthur and Flora. He found that they made an agreement which they intended should impose ‘mutual legal obligations’37 on each of them as to how their property was to be disposed. The agree-ment was that Arthur would leave his estate to her if, in return, she would leave hers to his children. The 1974 wills reflected that agreement, not the 1977 will.

Further comments on the nature of the agreement underpinning the doctrine of mutual wills were added by Morritt J in Re Dale.38 Morritt J confirmed that the doctrine did not just apply to where two testators had initially left their property to each other, as had occurred in Re Cleaver.

In Re Dale, Norman and Monica Dale wrote identical wills on 5 September 1988 in which they left all of their property to their son and daughter in equal shares. After Norman’s death, Monica wrote a new will in which she left £300 to their daughter but the remainder of all of her property to their son. After her death, her daughter brought an action claiming that the new will was of no effect and that the doctrine of mutual wills applied. A preliminary issue was whether the doctrine of mutual wills could apply to the facts of the case. In all previous cases where the doctrine had applied, the survivor of the two testators had initially left property to the other. It was argued, on the son’s behalf, that the surviving testator had to receive such a benefit for the doctrine of mutual wills to apply; that the receiving of such a benefit constituted the consideration upon which the contract to make mutual wills was based.

Morritt J held that the doctrine of mutual wills did not depend on showing mutual benefit between the two testators. It was not a prerequisite that each had to leave the other their property first. The doctrine simply depended on there being a contract between the two testators. Such a contract had to be supported by consideration, as with all contracts not made by deed. Sufficient consideration could be found on an executory basis by the first testator promising not to revoke his will whilst alive and, secondly, on an executed basis by the first testator not, in fact, revoking his will whilst alive.

Morritt J deduced that the foundation of the doctrine of mutual wills was originally the prevention of fraud. It would be a fraud on the deceased testator if the surviving testator was allowed to revoke their mutually agreed will and leave the property to beneficiaries other than those agreed between them. It was a fraud on the deceased testator not to uphold the mutual will and it made no difference to the committal of that fraud whether the surviving testator had benefited from the estate of the deceased testator.

In Re Goodchild, Dec’d,39 the Court of Appeal stressed that not only did an agreement have to be found between the testators, but that there also had to be a mutual intention found not to alter the wills after they had been made.

The facts concerned the wills of Dennis and Joan Goodchild. Each will left their property to the other, but if the other did not survive for 28 days after the first’s death, each residuary estate was left to their son, Gary. After Joan’s death, Dennis married Enid. He made a new will, in which he revoked his previous will and left everything to Enid.

Dennis died in 1993. Gary brought an action claiming that the doctrine of mutual wills applied and that Enid held his parents‘ residuary estate on constructive trust for him. This action was dismissed by Carnwath J and Gary appealed to the Court of Appeal.

Leggatt LJ set out the reason why the court was concerned to find an agreement between the testators as a prerequisite before holding that the doctrine of mutual wills applied:

the reason why, if mutual wills are to take effect, an agreement is necessary, is that without it the property of the second testator is not bound …40

Leggatt LJ said a ‘key feature’ of mutual wills was:

the irrevocability of the mutual intentions. Not only must they be binding when made, but the testators must have undertaken, and so must be bound, not to change their intentions after the death of the first testator.41

Finding such mutual intentions went beyond two testators leaving their estates to each other and thereafter to a chosen beneficiary. Such a plan did not carry with it a notion that it would be irrevocable. It had to be evidenced that the testators intended not to change their minds after the death of the first testator. For this, Leggatt LJ said:

The test must always be, suppose that during the lifetime of the surviving testator the intended beneficiary did something which the survivor regarded as unpardonable, would he or she be free not to leave the combined estate to him? The answer must be that the survivor is so entitled unless the testators agreed otherwise when they executed their wills. Hence the need for a clear agreement.42

On the facts, the doctrine of mutual wills did not apply. Dennis and Joan undoubtedly wanted Gary to inherit their residuary estates. But that was not sufficient to subject Enid to a constructive trust of the property in Gary’s favour because that was not enough to prevent Dennis from writing a new will. What was required was ‘a mutual intention that both wills should remain unaltered and that the survivor should be bound to leave the combined estates to the son’.43

Joan felt the arrangement was irrevocable but Dennis did not. They did not share a mutual intention to leave the property to Gary.

The case illustrates that it is not any agreement that will be sufficient to prove that the doctrine of mutual wills applies. The agreement must not only comply with the requirements set out in Re Cleaver, but also it must be made under an intention, shared by both parties, that the arrangement is irrevocable. Dennis thought that he had merely a moral obligation not to revoke his will but such obligation was not sufficient to establish that the doctrine applied.

Mutual wills v two identical wills

As has been seen, there is a difference between two wills which are subject to the doctrine of mutual wills and two wills that two testators make and are merely identical to one another. The key difference, of course, is that where mutual wills have been made, there is little point in the surviving testator altering their will due to the contract that they formed with the deceased testator. Equity will ensure that the agreed property is held by the surviving testator on constructive trust for the agreed beneficiaries.

It will not, it is suggested, often be the case that two individuals wish to make mutual wills and effectively surrender their freedom of testamentary disposition by doing so. If, however, two individuals do wish to make mutual wills, it is best practice for each will to state expressly that they are mutual wills, as well as being in the same form as each other. An express statement is the best possible evidence of a mutual intention that the testators intended to invoke the doctrine of mutual wills.

Revocation of mutual wills

Given what has been discussed, it might be thought that, provided the elements needed to establish mutual wills are found, it is impossible to revoke mutual wills. Whilst this is true after the first testator’s death, it is not the case whilst both testators remain alive. During the testators’ lifetimes, either one may revoke their mutual will, providing they give notice to the other. It is, of course, impossible to revoke a mutual will after the death of the first testator as at that point, the surviving testator will be subject to a constructive trust to hold the property for the agreed beneficiaries.

This was made clear in the case which was the basis of the doctrine of mutual wills in English law, Dufour v Pereira,44 where Lord Camden LC said45 a mutual will:

might have been revoked by both jointly; it might have been revoked separately, provided the party intending it had given notice to the other of such revocation. But I cannot be of opinion, that either of them, could, during their joint lives, do it secretly; or that after the death of either, it could be done by the survivor by another will.

Suppose two testators make mutual wills. Whilst they are both alive, one desires to alter their will. They give notice of that wish to the other The other refuses to give consent.

Freedom of testamentary disposition states that the one desiring to alter their will can do so. Lord Camden LC’s words also suggest that the agreement that the testators would write mutual wills can be broken.

But, in a sense, there is little point in breaking an agreement to make mutual wills if the other testator does not agree to it. If one testator materially alters their will, such altera-tion will not have any effect: Re Hobley.46

In this case, Mr and Mrs Hobley made mutual wills in favour of each other in 1975. They left their house to Mr Blythe, if one of them had predeceased the other. After making his will, Mr Hobley executed a codicil revoking the gift of the house to Mr Blythe. There was no evidence that Mrs Hobley knew of this act by her husband.

After his death, Mrs Hobley executed a further will which was different from the 1975 will. The issue for the High Court was whether this will was valid or whether a constructive trust had been imposed on her executors by the doctrine of mutual wills affecting the earlier wills.

Judge Charles Aldous QC held that Mrs Hobley’s later will was valid, due to the unilateral alteration made to the earlier mutual will by Mr Hobley. That alteration was sufficient to prevent the constructive trust arising.

The court found that any unilateral alteration without the consent of the other testator would prevent a constructive trust arising. The court could not try to embark on an exercise in discovering whether the alteration really mattered to the surviving testator Such evidence would be difficult to ascertain, as in usual cases involving mutual wills, both testators have died before litigation results.

Testators should, therefore, think carefully before making mutual wills and just as carefully before trying to alter them.

Mutual wills and the constructive trust

If it is found that two testators intended to execute mutual wills, equity forces the survivor to honour the agreement made with the deceased testator by means of the constructive trust. The constructive trust arises from the moment the first testator dies: Re Hagger.47

The facts concerned a document called the ‘joint will’ of John and Emma Hagger, written in 1902. The document stated that after the first of them had died, the income from their properties was to be paid to the survivor for life. After the survivor’s death, the estate was to be split between several named individuals.

Emma died in 1904. The income from their properties was paid to John for his life. In 1921, John made another will in which he left his estate to people who were not mentioned in the earlier joint will. By the time John died in 1928, three of the original beneficiaries, one of whom was Eleanor Palmer, under the joint will had themselves died. The issues for the court were (i) whether all of the property owned by John at the date of his death was to be left on the trusts declared in the joint will and (ii) who should receive the property left to Eleanor Palmer, as she had predeceased John. The argument was that her personal representatives were not entitled to it as her share lapsed on her death.

Clauson J held that a trust came into existence at the moment Emma died. At that stage, John became a trustee of the property in favour of the trusts declared in the will. John himself had no beneficial title to the property, other than the life interest in his favour. Consequently, Eleanor’s personal representatives were entitled to receive her share as it had not lapsed on her death. The trust had been constituted on Emma’s death.

The difficulty with holding that there is a constructive trust is that, in a case such as Re Hagger, John was entitled only to a life interest in the property during his lifetime. It is an interesting question as to precisely what and how much property is caught by the imposition of the constructive trust. In Re Hagger, the testators had regarded their property as jointly acquired by their joint efforts, so it was apt that the constructive trust covered all of the property left in the joint will. In other mutual wills, it must be best practice for testators to define precisely the property which they intend should be subject to the constructive trust. If no definition of property is given, it appears that the property will consist of the whole of the property owned by both testators, according to Lord Camden LC in Dufour v Pereira:48 ‘[t]he property of both is put into a common fund, and every devise is the joint devise of both.’

The Australian decision of Birmingham v Renfrew49 considered the extent to which the surviving testator could use the property if all of it had been subjected to a constructive trust by the mutual wills.

The facts concerned Joseph and Grace Russell. Grace had inherited a substantial amount of property from an uncle. Joseph had no property of his own. They came to an agreement in which, in their wills, Grace would leave the entire property to Joseph and in turn, he would leave it on his death to certain of her relatives. (The alternative would have been simply for Grace to leave Joseph a life interest in the property with the remainder interest to her relatives but such option was not pursued by her.) Both of them made wills to that effect. Grace died before Joseph, whereupon he made a different will under which he appointed different beneficiaries, leaving his former wife’s relatives with little or no property. The trial judge recognised the agreement formed by Joseph and Grace to the extent that a trust was recognised as being imposed over their property in favour of her relatives. Joseph’s relatives appealed to the High Court of Australia. Their appeal was dismissed.

The case is known for the interesting comments of Dixon J who considered the extent to which the surviving testator could make use of the property subject to the trust during his lifetime. He considered the trust to be ‘floating’50 in nature. This floating trust enabled the survivor to deal with the property as he wished during his lifetime but ensured that the property would always be subject to the agreed trusts on the survivor’s death. This occurred because the ‘floating obligation, suspended, so to speak, during the lifetime of the survivor can descend upon the assets at his death and crystallize into a trust’.51

The survivor could use the property as he wished during his lifetime and even convert realty into personalty if he so desired. He could spend money raised by the sale of the property but only to a point: Dixon J held that the survivor was not permitted to dispose of the property so that the intentions of the agreement made between the two testators would be defeated.

Dixon J also held that it was irrelevant that the two testators had not written down the terms of their agreement before they wrote their mutual wills, even though part of the property concerned land. The argument before him was that as the testators were creating a trust of land, they should have had to comply with the equivalent of s 53(1)(b) of the Law of Property Act 1925. This did not matter, as the contract formed by the testators was to operate not on any specific property, such as land, but on whatever assets the testatrix had at her death. In any event, the maxim underpinning the doctrine of mutual wills was that equity would not permit a statute to be used as an instrument of fraud. It was not possible for Joseph’s relatives to argue that the writing requirements of the equivalent of s 53(1)(b) had not been fulfilled as, had that argument been accepted, they would have been using those requirements to commit a fraud on both the testatrix and the original beneficiaries.

The analysis led by Dixon J in Birmingham v Renfrew of the notion of a floating trust over all of the property of the trust was accepted by the English courts in the decision of Nourse J in Re Cleaver.

The issue of the extent of the property subject to a constructive trust was considered recently by the Court of Appeal in Olins v Walters.52

The case concerned the wills of Harold and Freda Walters. Freda died in 2006. As Mummery LJ put it in giving the leading judgment, the ‘novel aspect’53 about the case was that Harold was still alive at the time of the litigation and thus could give first-hand evidence about the alleged agreement. He denied that he and Freda had ever made such an agreement that would subject them both to the doctrine of mutual wills.

Harold and Freda had made wills in 1988. Ten years later, they made codicils to their wills. These were drawn up by one of their grandsons, Andrew, who was a solicitor. Each codicil confirmed that it was supplementary to their earlier wills, which had been intended to be ‘mutual testamentary dispositions’. In a letter to his grandparents, Andrew explained the doctrine of mutual wills to them. He recorded that they wanted their wills to be mutual so that Freda would not be pressured into changing her will by their family should Harold predecease her.

By the time Freda died, Harold and Andrew’s relationship had deteriorated. Harold denied wishing to make a mutual will and said he could not recall the meeting in which he had instructed Andrew to draft the codicils or the agreement to make the wills mutual. Andrew began proceedings for a declaration that Freda’s codicil took effect as a valid mutual will. At first instance, Norris J held that there was a contract to make mutual wills between Harold and Freda. Harold appealed to the Court of Appeal. His appeal was unanimously dismissed.

Norris J had held that, as a matter of construction of the codicil, it was only Freda’s property that was subject to the constructive trust. He did not regard the issue of Harold’s estate as requiring determination. Harold submitted on appeal that this showed that there was little evidence as to the terms of the contract which was alleged to have been formed between him and Freda. He said that without evidence as to the terms of the contract, it was not appropriate to decide that the wills were mutual.

The Court of Appeal disagreed. Mummery LJ said that all that was required to establish the doctrine of mutual wills was evidence of the intentions of Harold and Freda. This gave rise to a trust which became binding on Harold when Freda died. The operation of the trust was not postponed to take effect from Harold’s death.

There was no need to search for the exact terms of the contract on which the mutual wills were based. Mummery LJ said that disputes as to the actual operation of the trust normally hinged on the construction of the agreement formed between the two testators. Such differences could be resolved informally between beneficiaries of sound mind and full age. If the beneficiaries lacked capacity, or could not agree, any dispute could be resolved by the court as and when necessary.

Olins v Walters shows that the court will take a pragmatic approach to the issue of the terms of the contract underpinning the constructive trust. The court will not seach exhaustively for all of its terms which will usually be a time-consuming exercise as normally both testators will have died before litigation reaches the court. Instead, the court will intervene only when required to answer specific questions that the beneficiaries have been unable to resolve for themselves. Prevention, however, remains better than cure and careful drafting of the subject matter of the trust which forms the agreement underpinning the mutual wills must remain the order of the day.

Mutual wills — the future

In general terms, it is suggested that mutual wills are a bad idea. Whilst they do prevent a surviving testator from being pressured into altering their will, they effectively tie up that survivor to an agreement formed perhaps many years previously in different circumstances to leave property to particular beneficiaries. For young couples in particular, mutual wills should be regarded with caution. The death of one of them at a young age will prohibit the survivor from altering their testamentary intentions with their property even though they may have subsequently formed a new life with a different individual. Indeed, Mummery LJ gave cautionary guidance in Olins v Walters:

The likelihood is that in future even fewer people will opt for such an arrangement and even more will be warned against the risks involved.54

The courts have indicated a wish not to try to define the extent of the property subject to a mutual will but rather, in Olins v Walters, to retain a watching brief over the administration of the deceased’s estate. Birmingham v Renfrew confirms that the surviving testator has freedom to use the property but such use is curtailed in that the property cannot be sold off in swathes such as would defeat the intentions of the deceased testator to leave it to particular beneficiaries.

Points to Review

You have seen:

![]() how secret trusts and mutual wills are based on the concept of agreement that takes effect outside of a testator’s will;

how secret trusts and mutual wills are based on the concept of agreement that takes effect outside of a testator’s will;

![]() that both secret trusts and mutual wills were based on the doctrine of fraud. Equity’s desire to prevent fraud continues to underpin mutual wills but the doctrine of secret trusts has moved away from fraud. Secret trusts now simply appear to be an example of equity’s enforcement of a validly created trust; and

that both secret trusts and mutual wills were based on the doctrine of fraud. Equity’s desire to prevent fraud continues to underpin mutual wills but the doctrine of secret trusts has moved away from fraud. Secret trusts now simply appear to be an example of equity’s enforcement of a validly created trust; and

![]() how, once made, it is a breach of the original agreement for one testator to revoke the mutual will unilaterally without the consent of the other testator and that revocation of the agreement after the first testator’s death is impossible, as equity will recognise a constructive trust of the property.

how, once made, it is a breach of the original agreement for one testator to revoke the mutual will unilaterally without the consent of the other testator and that revocation of the agreement after the first testator’s death is impossible, as equity will recognise a constructive trust of the property.

Making connections

The mechanism for enforcing mutual wills is that of a constructive trust. Constructive trusts are discussed in Chapter 3. You should turn to that chapter to refresh your memory on that topic.

Secret trusts and mutual wills also involve parol evidence being allowed to prove their existence. Depending on the type of property being left on trust, in theory this runs contrary to statutory requirements such as s 53(1)(b) of the Law of Property Act 1925 which requires all trusts of land to be evidenced in writing. Equity will not, however, allow a statute to be used to commit a fraud and in this context, will not permit someone to invoke a statute in order to deprive a rightful beneficiary of their property. The topic of formalities being required in relation to a trust being properly formed and equity’s views on a statute not being used as an instrument of fraud are discussed in Chapter 4.

Useful Things to Read

Useful Things to Read

The best reading is contained in the primary sources listed below. It is always good to consider the decisions of the courts themselves as this will lead to a deeper understanding of the issues involved. A few secondary sources are also listed, which you may wish to read to gain additional insights into the areas considered in this chapter.

Primary sources

Birmingham v Renfrew (1937) 57 CLR 666.

Blackwell v Blackwell [1929] AC 318.

McCormick v Grogan (1869–70) LR 4 HL 82.

Olins v Walters [2009] Ch 212.

Ottaway v Norman [1972] Ch 698.

Re Bateman’s WT [1970] 1 WLR 1463.

Re Cleaver [1981] 1 WLR 939.

Re Dale [1994] Ch31

Re Goodchild [1997] 1 WLR 1216.

Re Hagger [1930] 2 Ch 190.

Re Keen [1937] Ch 236.

Re Snowden [1979] Ch 528.

Secondary sources

Alastair Hudson, Equity & Trusts (7th edn, Routledge-Cavendish, 2012) ch 6.

Ruth Hughes, ‘Mutual wills’ (2011) PCB 3, 131–136. This article compares the constructive trust to proprietary estoppel in the context of mutual wills.