11

Making Videos Accessible

Society is inching towards accessibility for everyone when it comes to film and digital media content. Audiences with disabilities have been speaking up for their rights for some decades. Laws in many countries, including the United States, now require audio description and captioning for projects funded by taxpayer dollars, which has created larger pools of accessible content. And now technology is making it possible to deliver—efficiently and affordably—captioned and audio described content. Audiences are also eager for content that may not have been originated in their native language. Here again, technologies, such as artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning, are making automated processes faster, better, and more affordable. And there are plenty of humans also working to create more accessible content worldwide. The more content is created with all audiences in mind, the greater the audience demand for even more audio that is described, captioned, and translated, so it’s a win-win for content creators to acknowledge and serve the disability and translation communities.

In writing this chapter, I interviewed many people involved in bringing that content to life. They agree there are two keys: (1) be ready to provide an accurate transcript of your finished program, and (2) pauses help. We’re not talking about large gaps. Just small beats between dialogue sequences and scenes. Frankly, you should have them anyway. As we discuss in other chapters, there is an important storytelling role for moments without narration or dialogue. And luckily, when considering storytelling for a wider audience, we have a great advantage in the nonfiction world over those working in fiction. In narrative film, it would be uncommon to change the film in any way for translation, other than dubbing or adding captions. But in documentary and other nonfiction content forms, such as video for training, outreach, advocacy, etc., we have the ability to build different versions. These do not have to be wildly costly reedits. But we can give ourselves the flexibility to do a modest reedit with longer shots in some scenes, in order to accommodate a translated voiceover, audio description, or caption. For example, if I know in advance that a project is likely to be translated into many foreign languages, then I will include reminders on my shot list to roll a little “pad” before camera or talent action, and to hold shots longer after action before cutting. This gives me longer “handles” on those shots, so that when editing into a sequence I have some room to adjust shot length for a translation to catch up to the action. We can simply match back those shots, knowing we can add more frames here or there without fundamentally changing the shots or the sequence of shots. As you will learn later in this chapter, there are certain languages that require more time. And audio description and some captions may also benefit from less frantic pacing. To be clear, I’m not recommending you change the pace of the entire project—that could affect the impact of your story for all audiences. But it is worth being mindful about shot pacing and editing tempo so that we have options once we begin the work of audio description, captioning, or translation. Ultimately, we can be more successful storytellers if we reach a wider audience. Let’s take a look at the specific ways to make content accessible.

Audio Description and Access for Blind and Visually Impaired Audiences

According to the World Health Organization, about 1.3 billion people worldwide are living with some form of visual impairment. According to the National Federation of the Blind, more than 7 million blind or visually impaired adults live in the United States alone. Do you really want to lose all of these potential viewers of your content? Unfortunately—and I’m sadly including myself in this group—we sometimes don’t consider the needs of this audience up front, when developing productions. It turns out that it is not an excessively expensive or cumbersome process, but it does require a little advanced planning.

There is a simple way visually impaired viewers can access film content, and that is through a process called audio description. Audio description is an additional audio element that can be added to any soundtrack. Most broadcasters now have the capability to send out this signal, known as the Secondary Audio Programming (SAP) track, which you can access through the control settings on your television set. YouTube offers an Audio Description upload plugin. Once you upload your description, the plugin appears in the lower left and can be turned on and off, and volume can be adjusted.

Audio description cannot replace sound storytelling that isn’t present in the first place. If the critical contextual audio elements we’ve been talking about throughout this book are missing—wild sound, sync sound, appropriate music and sound effects, quality interviews, snippets of dialogue between characters—then everyone, not only the disability audience, is missing out on a better story. Your film should include enough compelling audio to deliver textured and nuanced storytelling. One of the ways to ensure this as you are working on your edit is to pay attention to what we call the “radio story.” Close your eyes and play back the cut. What do you hear? When you change locations, are you providing context through sound (not simply text on screen announcing the location)? Can we hear the birds in the trees for a scene in the woods, or the sounds of cars whizzing by for an establishing shot in the city? And what about your characters? Can we hear some familiar chitchat between a long-time couple before you cut to one of their interviews? Perhaps we can hear the sound of children playing in the house with a little snippet of b-roll before you launch into an interview with a busy mom. Or we hear the cacophony of a symphony orchestra warming up before you begin the scene about the conductor. When you build audio context throughout your film, including some spaces for “silence,” which is really room tone for that location, your story won’t exclusively lean on the description of the visuals and will be stronger for every audience.

To learn more about the process of audio description, I turned to one of the pioneers of the audio description field, Dr. Joel Snyder of Audio Description Associates. Dr. Snyder has a PhD in in accessibility and audio description from the Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain, and has been doing audio description for video since the 1980s. I have turned to Joel for several of my own productions. I’ll use a more informal Q&A format here, to delve into some of what I have learned in my discussions with him.

Q: How and when did audio description begin?

A: Audio description began as a formal service in 1981, with a group who had performing arts backgrounds putting together concepts and techniques for describing what was happening on stage for visually impaired audiences. It went quickly from performing arts to television when WGBH approached us about audio describing public television programs. Dr. Snyder wrote the first three pilot programs that were ever audio-described. The project became the Descriptive Video Service (DVS), originally launched for use by other public television stations. Sometimes the term “DVS” is still used today to refer to audio description.

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) issued a rule of four hours minimal description, which was later struck down in court. Then in 2010, Congress passed a law to mandate an FCC rule of nine hours a week of audio described content by the major American broadcast networks. In the United Kingdom, 15%–20% of all content is now audio described. While many VHS releases were audio described, once we moved to DVD, many of those audio descriptions were not included. In theaters, many movies are audio described because movie theaters are public places and therefore fall under the Americans with Disabilities Act. Eventually museums began picking it up for tours, etc. In his long career as an audio describer and advocate, Dr. Snyder has described sporting events, funerals, weddings, parades—wherever the visual is critical to the understanding the event.

Q: How much content is audio described now?

A: According to Dr. Snyder, in the United States, a considerable volume of content is audio described. Any content created by anyone receiving US Federal government funds (Section 508 of the Rehabilitation Act and recipients of government money) must make their materials accessible. Corporations are also required to do this now. For example, Microsoft is very sensitive to disability concerns and making all of their thousands of training videos accessible. Most major feature films, content for DVDs and Blu-rays, and content on streaming services is now also accessible. The American Council of the Blind keeps track of content being audio described and available through Amazon and Netflix (see our Resources section for these links).

Q: Even if it’s not legally required, why should content creators care about accessibility to the visually impaired?

“If you aren’t considering the blind and visually impaired audience, you aren’t tapping what has been an underserved market,” says Dr. Synder. And he’s right. We’re talking about millions of Americans who are either blind or have trouble seeing, even with correction. I (Amy) was recently approached at a University speaking engagement by a blind audience member who wanted to watch a film I had mentioned producing in my talk. I had to admit to her that it had not yet been audio described. (It has now.) Thinking through the timeline for release and ensuring timely release for all audiences is an important step in post-production workflow for content creators.

Q: What are the new innovations for accessibility?

A: Half a dozen apps for mobile phones have come out recently, such as Actiview, which allows your smartphone to hear what’s going on in the movie theatre and then sync to an audio description track you downloaded in advance into your app. You use your earbuds to access this track while you are watching the movie. Actiview is also available for translations. We expect to see more of these apps entering the market for smartphone users. [Author’s note: These apps are a big step forward, as the headphones available at many movie theaters aren’t always reliable.]

Q: What are the biggest obstacles when providing audio description?

A: Creating a good audio description track takes time. It is a more nuanced process than simply transcribing the content for captions. It takes the initial audio description writer about one hour for every three to four minutes of content. That material needs to be reviewed by another person experienced with audio description to be sure it is accurate and uses good storytelling techniques. Then the track gets voiced, recorded, and edited into whatever format the client or filmmaker needs. Dr. Snyder explains:

“When I teach audio description, I emphasize the skills needed: discernment to cut out unnecessary elements, a superior vocabulary, and the ability to be both vivid and concise at the same time. It is also important to have the vocal skills to perform the script.”

An important component of audio description, which also applies to captioning, is to ensure you are not providing more than what is available to the sighted viewer. In other words, do not give away the plot.

“If there’s a gun on that desk and you know it will go off by the end of the scene, you want to incorporate a mention of the gun in your description, but you don’t want to overdo it and ruin the suspense” explains Snyder.

Q: Is there something content creators should do to make your job easier?

A: Dr. Snyder is clear about his role:

“Audio describers work in service to an audience that is underserved, and are also in service to the film art form as it is given to us. It’s not really our place to tell the creators to put in more pauses to make our job easier.”

[I will disagree slightly here, just to say that one of the reasons we included this chapter in our book was to call attention to the workflow for accessibility. While we don’t want to recommend unnecessary pauses, we find the lack of “space” in films to have a negative effect on storytelling and the ability for any audience to keep up with what is happening on screen.]

Q: What is the most difficult project you ever described?

A: Live description for televised events is inherently dicey because you haven’t had a chance to review anything. You can do lots of preparation. For example, Dr. Snyder has voiced many Presidential Inaugurations, and spends time understanding the order of events and the key political figures and performers involved. He also likes to prepare a series of synonyms, since in a multi-hour event, he doesn’t want to tell a boring story for the blind or visually impaired audience. A 15-second spot is one of the most challenging types of content. Less dialogue or narration provides at least a bit of room for creating an audio track with some space. Listening to several audio spots described by Joel, I felt like my ears were numb trying to keep up with such fast-paced, cutting action on screen, despite his heroic efforts to make the pacing less frantic.

Q: What is the workflow for audio description? Take us through the process.

A: The following are what an audio description service will need from you in order to create your track:

Total runtime of your film or video

What is/are the deliverable(s)? Do you just need the audio description track timed to fit within the pauses of the film and you will lay it back? Or do you want the service to handle this editing process? (In which case you will need to deliver the files they request to make that possible). Do you need a script in advance for approval?

A copy of the film in final picture-locked form—meaning you will not be making any additional changes to the timing of scenes.

A list of any special or unusual names or acronyms and a guide on how to pronounce them.

Any special factual information related to your content (for example, if you have produced a training film, the correct names of any equipment the describer will need to use as they describe scenes).

Notes from a Blind Viewer

Itto Outini has another perspective. A Fulbright Scholar in the graduate program for Journalism and Strategic Media at the University of Arkansas, Outini believes that blind audience members like her can intuit plenty of content without audio description as long as there is a rich, contextual soundtrack. Outini uses as an example the multi-media documentary ‘Half the Sky: Turning Oppression into Opportunity for Women Worldwide’ (PBS, 2012) inspired by the Nicolas Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn book of the same name. She recalls a scene by the ocean:

“I didn’t need someone to tell me they are driving next to the ocean, because I could hear it. He was interviewing them in the car with the windows open. The sound quality was just great. I didn’t need audio description to tell me where they were.”

She also doesn’t appreciate audio description that does not propel the story. Ultimately, she believes—as we do—that sound communicates a deep level of the story without words. Outini puts it quite simply: “If you are telling the story without sound, you are killing storytelling.”

Captioning and Access for Deaf and Hearing Impaired Audiences

According to the World Health Organization, we know that 360 million people worldwide have moderate to profound hearing loss. This number includes 36 million American adults. That’s almost 1 out of 10 who have some degree of hearing loss. So again, a significant audience for your content. The solution for this audience has been to provide captions. (There is some content that is signed, but given the vast number of different signing languages and the cost of inserting signers, this content is somewhat limited. For more on this, see the Resources section at the end of the book) (Figure 11.1).

The deaf and hard of hearing community first made inroads in captioning for feature films with the Captioned Film Act of 1958. It took more than a decade for the emergence of the First National Conference on Television for the Hearing Impaired in 1971, where two possible technologies for captioning television programs debuted. Both technologies displayed the captions only on specially equipped sets for deaf and hard-of-hearing viewers. Another demonstration of closed captioning followed at Gallaudet College (now Gallaudet University) on February 15, 1972. ABC and the National Bureau of Standards presented closed captions embedded within the normal broadcast of “Mod Squad.” This fantastic achievement proved the technical viability of closed captioning.

FIGURE 11.1 Captioning makes your video more widely accessible.

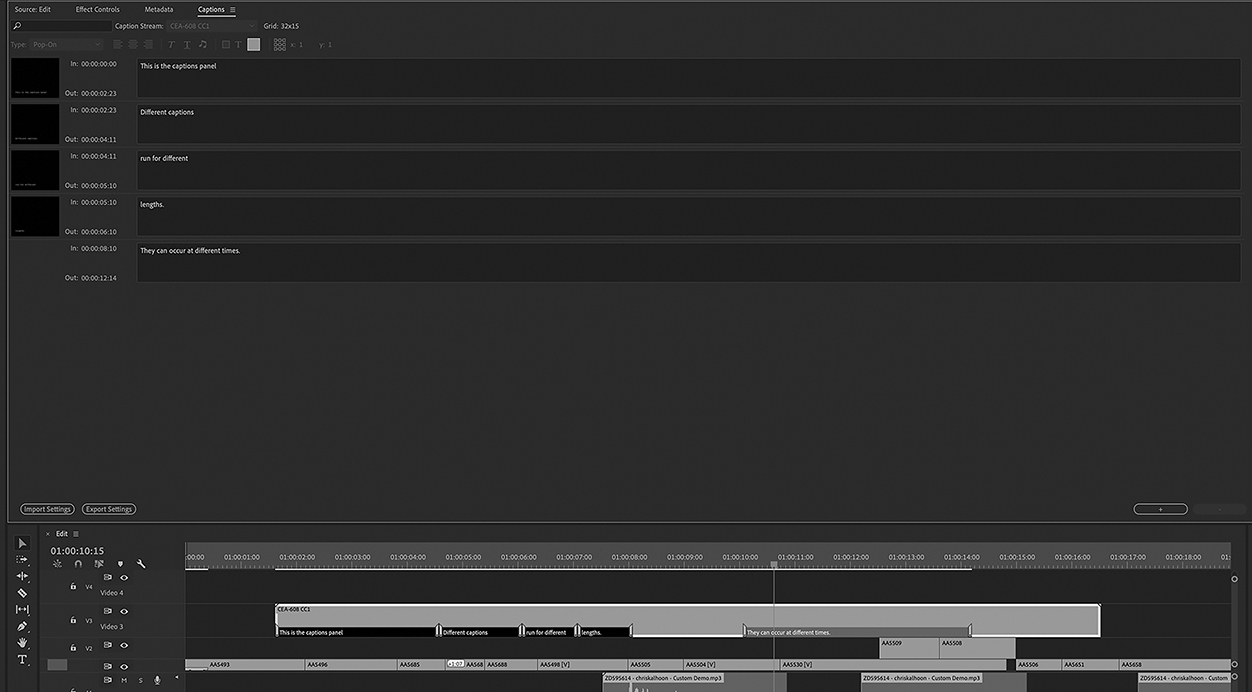

Since that time, captioning has come a long way. In fact, these days hearing audiences also consume a large amount of captioned content. Facebook claims that 85% of its videos are viewed without sound (at least the first time through). All NLEs now provide an easy way to upload captions during the editing process. YouTube supports uploading captions you have created or can generated them using AI. Machine learning is pushing AI-created captions forward by leaps and bounds, making them more accurate. Today’s NLEs include captioning as part of their features. Web hosting platforms also offer captioning options.

Post production expert Katie Hinsen wrote an excellent deep dive on accessibility on the Frame.io blog which I highly recommend. Called Design for the Edges: Video for the Blind and Deaf (September 4, 2018), the article highlights both the care and workflow required to put audiences truly on an equal footing and notes new tools that are making the creation of accessible content more affordable for content creators. These include Amara, which crowdsources captioning and translation, and Subtitle Edit, a free online tool for creating caption files. Further, AI-enhanced caption automating tools are now being incorporated into video hosting platforms, such as Brightcove.

Perspectives on Captioning from Deaf Audiences

While television has made significant advances and most programming are now captioned, watching films in a theatre setting still creates obstacles for deaf and hard-of-hearing audience members. Dolby has created the CaptiView system, a captioning device that fits into a cupholder (Figure 11.2). And Sony has created a set of glasses that provides captioning in the field of view. But it is up to theatre owners to purchase and maintain these devices. According to patrons who use them, they often do not. As a result, many in the deaf community have been pressing for open captioning for all feature films. John Stanton, a board member of the Alexander Graham Bell Association for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing, gave me feedback on his personal experiences as a media consumer. John explained a typical problem he had on a recent visit to see the new Spider Man movie:

“I had to throw my winter coat over the gooseneck [screen-holder] to keep it in place for me to read the caption box. Naturally, I told this to the guy at guest services when the movie was over. He didn’t look like he gave a…”

FIGURE 11.2 CaptiView system in a movie theater (courtesy: Bozeman Daily Chronicle, Rachel Leathe, Photographer).

One of the top places for nonfiction content viewing is airline flights, so cutting off a large portion of the audience should concern us as nonfiction filmmakers. Thanks to efforts by travelling customers and many organizations across the disability community, accessibility of content on airlines has made some significant advances in the last few years. In 2016, the U.S. Department of Transportation established an Advisory Committee on Accessible Air Transportation. The resulting agreement made several important changes that affect customers, and those producing content that will be used on aircraft in-flight entertainment systems. Now, 100% of this content must be both audio described and captioned. In addition, the airlines’ in-flight entertainment systems must be capable of supporting both closed captions and audio descriptions. If they cannot provide these systems, for example on older aircraft, then airlines must offer an alternative accessible entertainment device. In addition, airlines must offer accessible Wi-Fi for blind and visually impaired passengers to ensure that cabin announcements can be understood by all.

Captioning has not solved all problems for the deaf community. When I interviewed John Stanton about his feedback as a deaf consumer of media content, one of his concerns was that films containing music with lyrics stop captioning as soon as any singing starts—in effect, cutting off the “sound” for the deaf viewers for large chunks of movies, particularly musicals, and any television shows in which the plot is often supported through pop song lyrics in the soundtrack. This makes watching a disrupted experience, at best. The argument from studios has been that they do not have the proper license to caption the lyrics. You can read John’s impassioned legal argument against this practice in his article published in the UCLA Entertainment Law Review (2015) “Why Movie and Television Producers Should Stop Using Copyright as an Excuse Not to Caption Song Lyrics.” For your own productions, you will make your decisions on how and when to caption. But now that John Stanton and others have raised my awareness, I will be much more sensitive to my captioning choices.

The Captioning Process

We’ve been talking about captions from an audience perspective. Now let’s take a look at captioning from the filmmaker point of view. Dave Evans, who owns Tempo Media in Tucson, Arizona, gave me some insights on the process. His company handles both captioning and some re-editing and translation services as well. Dave noted there are certain types of nonfiction content that make captioning easier to do than others. For example, when you simply have a talking head on camera, it is easier to sync up the captions and even use AI tools to do it. But when there are sound effects or other audio tracks to consider—and we hope there are, if you agree with our philosophy in this book—then more finesse is required. When working to caption film productions, he is mindful of not getting ahead of the plot, or putting too much verbiage on the screen at the same time. This is called the “presentation rate,” and while some captioning software will tell you that it is getting too high, it doesn’t tell you how to solve the problem. Solving pacing issues is one of the top challenges that Dave manages when captioning. Another issue is placement. So before filming, consider how your composition will appear once captions are added. If you are shooting an interview, do you need to frame extremely tight? Where will names and subtitles go? One of the reasons I like to shoot in 4K or 4K UHD is to have extra screen space for re-cropping or adjusting as needed for titling or captions. This only works, of course, if you are delivering in 2K or less. For most of my nonprofit clients, this is a sufficient delivery spec. Shooting in 4K gives us the added bonus of a higher resolution format for future-proofing.

Making Foreign Language Translations

Foreign language translations are essential for many productions. When working on certain kinds of content, such as training content for multinational corporations or educational content for organizations reaching immigrants with a primary language different from that of the original program, you will need translation services. This means planning ahead in three key areas. First, you will need to make sure your workflow includes creating an accurate script of the final version of your project. I call this the “as aired” script, as opposed to the many different rough cut and fine cut versions that may have preceded it. And I recommend putting a PDF version of this script into your export folder as well as a documents folder that is part of your project files on your NLE. Sometimes translated or captioned versions are created many weeks, months, or even years after the initial project release, so it’s helpful to have this file easily accessible to someone accessing your project editing files (Figure 11.3).

FIGURE 11.3 Most NLEs have a subtitling tool (labeled sub caption).

Second, you will want to think about any on-screen text. If you have a lot of text, consider breaking it up so that it is not too dense, making translation and insertion into the same space difficult. Dave Evans’ experience confirms this: “We do a lot of on screen text replacement, for example replacing all the English bullet points on screen with bullet points in Portuguese, which takes up more space on screen.” He also sometimes has to match a wipe to bring on a lower third name, and will have to mask the original wipe unless he is provided with the project folders and files. So ideally, you will want to make those original files available to your translation and captioning agency so they have clean material to work with.

Finally, think about your pacing. We spoke at the outset of this chapter on how shot length and edit pacing can affect your ability to deliver effective versions that are audio-described, dubbed, or captioned. In the area of translations, remember that many languages have differing lengths from one another when delivering the same sentence or information. Michael Collins of Glenwood Sound, who provides translation, voiceover, and dubbing services, known as “media localization,” explains that romance languages run 10%–15% longer than English, some Scandinavian languages can run shorter, and German can have a similar length, but higher syllable count than English. While he often is only able to work with the film as it is delivered, in some cases he needs the right to edit the film in order to make the overdubbing work for the film and audience. Remember that when hiring talent to voice your film in another language, you will want to consider regional accents and syntax differences. A Spanish-speaking voiceover with a Honduran accent would not necessarily be well received by Spanish-speaking audiences viewing your production in Spain.

If you are thinking about dubbing your film translation rather than captioning, consider which of the three types of dubbing would best suit your project:

Lip Sync—Used for scenes with dialogue, and therefore most commonly used for fiction films, this type of dubbing is the most nuanced and complex. It requires syllable-matching, and is done sentence by sentence by the voiceover artist you select. They might even have to memorize lines and try to match it with what is on screen. As you might expect, this type of dubbing can be expensive. Big Hollywood movies and large-release documentaries will spend the money to be sure every lip movement is matched with what is known as “theatrical” dubbing. A less precise version of lip sync dubbing called “modified” means the talent won’t match every syllable, but will at least try to make the sentences all start and stop together.

United Nations-Style—In this type of dubbing, you hear a second or two of the original language; for example, in the first few words of an interview, and then you hear the voice speaking the translation. This type of dubbing is ideal for documentary, because it gives the audience the sense of the real person on camera.

Timed Narration—For narrated productions, a narrator reading a translation will follow the video, the timecode on her script, or a combination. She establishes a rhythm that roughly follows the pacing of the original language and tries to align the content as well as possible with the footage on screen.

Costs

There are a range of costs associated with audio description, captioning, and translations. Let’s start with audio description. Some audio description services charge by the minute—at the time of publication, the rate was around $20/minute. Dr. Snyder’s company charges a minimum base rate of $350 for 10 minutes or less of content. This fee covers writing, voicing (he does his own, typically), recording, editing, layback, and delivery in any format. So, a one-hour documentary could cost you about $1,100. When you consider the millions of additional possible viewers, that isn’t a bad rate. But it is something you need to include in your budget at the start of production.

Language translation services generally charge by the word of the originating language. So, if your “as aired” script is 10,000 words, at a rate of approximately 10–20 cents per word that would run you $1,000–2,000. You will also pay a talent fee, and sometimes a recording fee, for someone to dub your production. For non-sync recording, talent typically charges by the word. For sync recording, talent will charge a per minute base rate. $75 per minute is standard in the United States.

More producers are using built-in captioning features of many NLEs or using AI tools, such as the one built into YouTube’s uploader. Just be mindful that these captions may be inaccurate and incorrectly placed for a quality viewing experience. If you pay a service for captioning, the fees can range from $1 to $15 per minute, depending on if they need to do any significant on-screen text masking and replacement or even reediting to accommodate the titles. If you plan to handle your own captioning, remember that captions must be accurate to pass muster with the FCC, Described and Captioned Media Program (DCMP), and Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG).

Tips for Accessibility

![]() More than 1.6 billion people worldwide have visual impairment or hearing loss. Making our content more accessible through audio description and captioning is imperative.

More than 1.6 billion people worldwide have visual impairment or hearing loss. Making our content more accessible through audio description and captioning is imperative.

![]() Remember that it takes time to audio describe scenes, so whenever possible, edit scenes with some “space” and consider adding a few beats of silence. It will help the story overall, and assist with the audio description process.

Remember that it takes time to audio describe scenes, so whenever possible, edit scenes with some “space” and consider adding a few beats of silence. It will help the story overall, and assist with the audio description process.

![]() Captioning is a multi-part process, starting with an accurate script. Remember that captions should include sounds, such as sound effects and sync sounds, not just spoken dialogue and narration.

Captioning is a multi-part process, starting with an accurate script. Remember that captions should include sounds, such as sound effects and sync sounds, not just spoken dialogue and narration.

![]() Consider your framing when shooting so that you have space for captions once you get into your edit.

Consider your framing when shooting so that you have space for captions once you get into your edit.

![]() Always play through audio described and captioned content to check for accuracy and to be sure you are not letting the descriptions or captions “get ahead” of the story. You want the experience to be equally good for all audiences.

Always play through audio described and captioned content to check for accuracy and to be sure you are not letting the descriptions or captions “get ahead” of the story. You want the experience to be equally good for all audiences.