Conflicts

7.0 INTRODUCTION

PMBOK® Guide, 4th Edition

9.4 Manage Project Team

9.4.2.3 Conflict Management

In discussing the project environment, we have purposely avoided discussion of what may be its single most important characteristic: conflicts. Opponents of project management assert that the major reason why many companies avoid changeover to a project management organizational structure is either fear or an inability to handle the resulting conflicts. Conflicts are a way of life in a project structure and can generally occur at any level in the organization, usually as a result of conflicting objectives.

The project manager has often been described as a conflict manager. In many organizations the project manager continually fights fires and crises evolving from conflicts, and delegates the day-to-day responsibility of running the project to the project team members. Although this is not the best situation, it cannot always be prevented, especially after organizational restructuring or the initiation of projects requiring new resources.

The ability to handle conflicts requires an understanding of why they occur. Asking and answering these four questions may help handle and prevent conflicts.

- What are the project objectives and are they in conflict with other projects?

- Why do conflicts occur?

- How do we resolve conflicts?

- Is there any type of analysis that could identify possible conflicts before they occur?

7.1 OBJECTIVES

Each project must have at least one objective. The objectives of the project must be made known to all project personnel and all managers, at every level of the organization. If this information is not communicated accurately, then it is entirely possible that upper-level managers, project managers, and functional managers may all have a different interpretation of the ultimate objective, a situation that invites conflicts. As an example, company X has been awarded a $100,000 government contract for surveillance of a component that appears to be fatiguing. Top management might view the objective of this project to be discovering the cause of the fatigue and eliminating it in future component production. This might give company X a “jump” on the competition. The division manager might just view it as a means of keeping people employed, with no follow-on possibilities. The department manager can consider the objective as either another job that has to be filled, or a means of establishing new surveillance technology. The department manager, therefore, can staff the necessary positions with any given degree of expertise, depending on the importance and definition of the objective.

Project objectives must be:

- Specific, not general

- Not overly complex

- Measurable, tangible, and verifiable

- Appropriate level, challenging

- Realistic and attainable

- Established within resource bounds

- Consistent with resources available or anticipated

- Consistent with organizational plans, policies, and procedures

Some practitioners use the more simplistic approach of defining an objective by saying that the project's objective must follow the SMART rule, whereby:

- S = specific

- M = measurable

- A = attainable

- R = realistic or relevant

- T = tangible or time bound

Unfortunately, the above characteristics are not always evident, especially if we consider that the project might be unique to the organization in question. As an example, research and development projects sometimes start out general, rather than specific. Research and development objectives are reestablished as time goes on because the initial objective may not be attainable. As an example, company Y believes that they can develop a high-energy rocket-motor propellant. A proposal is submitted to the government, and, after a review period, the contract is awarded. However, as is the case with all R&D projects, there always exists the question of whether the objective is attainable within time, cost, and performance constraints. It might be possible to achieve the initial objective, but at an incredibly high production cost. In this case, the specifications of the propellant (i.e., initial objectives) may be modified so as to align them closer to the available production funds.

Many projects are directed and controlled using a management-by-objective (MBO) approach. The philosophy of management by objectives:

- Is proactive rather than reactive management

- Is results oriented, emphasizing accomplishment

- Focuses on change to improve individual and organizational effectiveness

Management by objectives is a systems approach for aligning project goals with organizational goals, project goals with the goals of other subunits of the organization, and project goals with individual goals. Furthermore, management by objectives can be regarded as a:

- Systems approach to planning and obtaining project results for an organization

- Strategy of meeting individual needs at the same time that project needs are met

- Method of clarifying what each individual and organizational unit's contribution to the project should be

Whether or not MBO is utilized, project objectives must be set.

7.2 THE CONFLICT ENVIRONMENT

In the project environment, conflicts are inevitable. However, as described in Chapter 5, conflicts and their resolution can be planned for. For example, conflicts can easily develop out of a situation where members of a group have a misunderstanding of each other's roles and responsibilities. Through documentation, such as linear responsibility charts, it is possible to establish formal organizational procedures (either at the project level or company-wide). Resolution means collaboration in which people must rely on one another. Without this, mistrust will prevail.

The most common types of conflicts involve:

- Manpower resources

- Equipment and facilities

- Capital expenditures

- Costs

- Technical opinions and trade-offs

- Priorities

- Administrative procedures

- Scheduling

- Responsibilities

- Personality clashes

Each of these conflicts can vary in relative intensity over the life cycle of a project. However, project managers believe that the most frequently occurring conflicts are over schedules but the potentially damaging conflicts can occur over personality clashes. The relative intensity can vary as a function of:

- Getting closer to project constraints

- Having only two constraints instead of three (i.e., time and performance, but not cost)

- The project life cycle itself

- The person with whom the conflict occurs

Sometimes conflict is “meaningful” and produces beneficial results. These meaningful conflicts should be permitted to continue as long as project constraints are not violated and beneficial results are being received. An example of this would be two technical specialists arguing that each has a better way of solving a problem, and each trying to find additional supporting data for his hypothesis.

Conflicts can occur with anyone and over anything. Some people contend that personality conflicts are the most difficult to resolve. Below are several situations. The reader might consider what he or she would do if placed in the situations.

- Two of your functional team members appear to have personality clashes and almost always assume opposite points of view during decision-making. They are both from the same line organization.

- Manufacturing says that they cannot produce the end-item according to engineering specifications.

- R&D quality control and manufacturing operations quality control argue as to who should perform a certain test on an R&D project. R&D postulates that it is their project, and manufacturing argues that it will eventually go into production and that they wish to be involved as early as possible.

- Mr. X is the project manager of a $65 million project of which $1 million is subcontracted out to another company in which Mr. Y is the project manager. Mr. X does not consider Mr. Y as his counterpart and continually communicates with the director of engineering in Mr. Y's company.

Ideally, the project manager should report high enough so that he can get timely assistance in resolving conflicts. Unfortunately, this is easier said than done. Therefore, proj-ect managers must plan for conflict resolution. As examples of this:

- The project manager might wish to concede on a low-intensity conflict if he knows that a high-intensity conflict is expected to occur at a later point in the project.

- Jones Construction Company has recently won a $120 million effort for a local company. The effort includes three separate construction projects, each one beginning at the same time. Two of the projects are twenty-four months in duration, and the third is thirty-six months. Each project has its own project manager. When resource conflicts occur between the projects, the customer is usually called in.

- Richard is a department manager who must supply resources to four different projects. Although each project has an established priority, the project managers continually argue that departmental resources are not being allocated effectively. Richard now holds a monthly meeting with all four of the project managers and lets them determine how the resources should be allocated.

Many executives feel that the best way of resolving conflicts is by establishing priorities. This may be true as long as priorities are not continually shifted around. As an example, Minnesota Power and Light established priorities as:

- Level 0: no completion date

- Level 1: to be completed on or before a specific date

- Level 2: to be completed in or before a given fiscal quarter

- Level 3: to be completed within a given year

This type of technique will work as long as there are not a large number of projects in any one level.

The most common factors influencing the establishment of project priorities include:

- The technical risks in development

- The risks that the company will incur, financially or competitively

- The nearness of the delivery date and the urgency

- The penalties that can accompany late delivery dates

- The expected savings, profit increase, and return on investment

- The amount of influence that the customer possesses, possibly due to the size of the project

- The impact on other projects or product lines

- The impact on affiliated organizations

The ultimate responsibility for establishing priorities rests with top-level management. Yet even with priority establishment, conflicts still develop. David Wilemon has identified several reasons why conflicts still occur1:

- The greater the diversity of disciplinary expertise among the participants of a project team, the greater the potential for conflict to develop among members of the team.

- The lower the project manager's degree of authority, reward, and punishment power over those individuals and organizational units supporting his project, the greater the potential for conflict to develop.

- The less the specific objectives of a project (cost, schedule, and technical performance) are understood by the project team members, the more likely it is that conflict will develop.

- The greater the role of ambiguity among the participants of a project team, the more likely it is that conflict will develop.

- The greater the agreement on superordinate goals by project team participants, the lower the potential for detrimental conflict.

- The more the members of functional areas perceive that the implementation of a project management system will adversely usurp their traditional roles, the greater the potential for conflict.

- The lower the percent need for interdependence among organizational units supporting a project, the greater the potential for dysfunctional conflict.

- The higher the managerial level within a project or functional area, the more likely it is that conflicts will be based upon deep-seated parochial resentments. By contrast, at the project or task level, it is more likely that cooperation will be facilitated by the task orientation and professionalism that a project requires for completion.

7.3 CONFLICT RESOLUTION

PMBOK® Guide, 4th Edition

9.4.2.3 Conflict Management

Although each project within the company may be inherently different, the company may wish to have the resulting conflicts resolved in the same manner. The four most common methods are:

- The development of company-wide conflict resolution policies and procedures

- The establishment of project conflict resolution procedures during the early planning activities

- The use of hierarchical referral

- The requirement of direct contact

Many companies have attempted to develop company-wide policies and procedures for conflict resolution, but this method is often doomed to failure because each project and conflict is different. Furthermore, project managers, by virtue of their individuality, and sometimes differing amounts of authority and responsibility, prefer to resolve conflicts in their own fashion.

A second method for resolving conflicts, and one that is often very effective, is to “plan” for conflicts during the planning activities. This can be accomplished through the use of linear responsibility charts. Planning for conflict resolution is similar to the first method except that each project manager can develop his own policies, rules, and procedures.

Hierarchial referral for conflict resolution, in theory, appears as the best method because neither the project manager nor the functional manager will dominate. Under this arrangement, the project and functional managers agree that for a proper balance to exist their common superior must resolve the conflict to protect the company's best interest. Unfortunately, this is not realistic because the common superior cannot be expected to continually resolve lower-level conflicts and it gives the impression that the functional and project managers cannot resolve their own problems.

The last method is direct contact in which conflicting parties meet face-to-face and resolve their disagreement. Unfortunately, this method does not always work and, if continually stressed, can result in conditions where individuals will either suppress the identification of problems or develop new ones during confrontation.

Many conflicts can be either reduced or eliminated by constant communication of the project objectives to the team members. This continual repetition may prevent individuals from going too far in the wrong direction.

7.4 UNDERSTANDING SUPERIOR, SUBORDINATE, AND FUNCTIONAL CONFLICTS2

PMBOK® Guide, 4th Edition

9.4.2.3 Conflict Management

In order for the project manager to be effective, he must understand how to work with the various employees who interface with the project. These employees include upper-level management, subordinate project team members, and functional personnel. Quite often, the project manager must demonstrate an ability for continuous adaptability by creating a different working environment with each group of employees. The need for this was shown in the previous section by the fact that the relative intensity of conflicts can vary in the life cycle of a project.

The type and intensity of conflicts can also vary with the type of employee, as shown in Figure 7-1. Both conflict causes and sources are rated according to relative conflict intensity. The data in Figure 7-1 were obtained for a 75 percent confidence level.

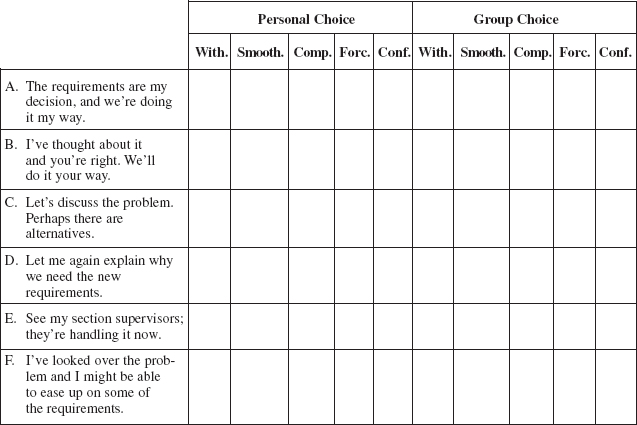

In the previous section we discussed the basic resolution modes for handling conflicts. The specific mode that a project manager will use might easily depend on whom the conflict is with, as shown in Figure 7-2. The data in Figure 7-2 do not necessarily show the modes that project managers would prefer, but rather identify the modes that will increase or decrease the potential conflict intensity. For example, although project managers consider, in general, that withdrawal is their least favorite mode, it can be used quite effectively with functional managers. In dealing with superiors, project managers would rather be ready for an immediate compromise than for face-to-face confrontation that could favor upper-level management.

Figure 7-3 identifies the various influence styles that project managers find effective in helping to reduce potential conflicts. Penalty power, authority, and expertise are considered as strongly unfavorable associations with respect to low conflicts. As expected, work challenge and promotions (if the project manager has the authority) are strongly favorable.

FIGURE 7-1. Relationship between conflict causes and sources.

FIGURE 7-2. Association between perceived intensity of conflict and mode of conflict resolution.

FIGURE 7-3. Association between influence methods of project managers and their perceived conflict intensity.

7.5 THE MANAGEMENT OF CONFLICTS3

PMBOK® Guide, 4th Edition

9.4.2.3 Conflict Management

Good project managers realize that conflicts are inevitable, but that good procedures or techniques can help resolve them. Once a conflict occurs, the project manager must:

- Study the problem and collect all available information

- Develop a situational approach or methodology

- Set the appropriate atmosphere or climate

If a confrontation meeting is necessary between conflicting parties, then the project manager should be aware of the logical steps and sequence of events that should be taken. These include:

- Setting the climate: establishing a willingness to participate

- Analyzing the images: how do you see yourself and others, and how do they see you?

- Collecting the information: getting feelings out in the open

- Defining the problem: defining and clarifying all positions

- Sharing the information: making the information available to all

- Setting the appropriate priorities: developing working sessions for setting priorities and timetables

- Organizing the group: forming cross-functional problem-solving groups

- Problem-solving: obtaining cross-functional involvement, securing commitments, and setting the priorities and timetable

- Developing the action plan: getting commitment

- Implementing the work: taking action on the plan

- Following up: obtaining feedback on the implementation for the action plan

The project manager or team leader should also understand conflict minimization procedures. These include:

- Pausing and thinking before reacting

- Building trust

- Trying to understand the conflict motives

- Keeping the meeting under control

- Listening to all involved parties

- Maintaining a give-and-take attitude

- Educating others tactfully on your views

- Being willing to say when you were wrong

- Not acting as a superman and leveling the discussion only once in a while

Thus, the effective manager, in conflict problem-solving situations:

- Knows the organization

- Listens with understanding rather than evaluation

- Clarifies the nature of the conflict

- Understands the feelings of others

- Suggests the procedures for resolving differences

- Maintains relationships with disputing parties

- Facilitates the communications process

- Seeks resolutions

7.6 CONFLICT RESOLUTION MODES

PMBOK® Guide, 4th Edition

9.4.2.3 Conflict Management

The management of conflicts places the project manager in the precarious situation of having to select a conflict resolution mode (previously defined in Section 7.4). Based upon the situation, the type of conflict, and whom with, any of these modes could be justified.

Confronting (or Collaborating)

With this approach, the conflicting parties meet face-to-face and try to work through their disagreements. This approach should focus more on solving the problem and less on being combative. This approach is collaboration and integration where both parties need to win. This method should be used:

- When you and the conflicting party can both get at least what you wanted and maybe more

- To reduce cost

- To create a common power base

- To attack a common foe

- When skills are complementary

- When there is enough time

- When there is trust

- When you have confidence in the other person's ability

- When the ultimate objective is to learn

Compromising

To compromise is to bargain or to search for solutions so both parties leave with some degree of satisfaction. Compromising is often the result of confrontation. Some people argue that compromise is a “give and take” approach, which leads to a “win-win” position. Others argue that compromise is a “lose-lose” position, since neither party gets everything he/she wants or needs. Compromise should be used:

- When both parties need to be winners

- When you can't win

- When others are as strong as you are

- When you haven't time to win

- To maintain your relationship with your opponent

- When you are not sure you are right

- When you get nothing if you don't

- When stakes are moderate

- To avoid giving the impression of “fighting”

Smoothing (or Accommodating)

This approach is an attempt to reduce the emotions that exist in a conflict. This is accomplished by emphasizing areas of agreement and de-emphasizing areas of disagreement. An example of smoothing would be to tell someone, “We have agreed on three of the five points and there is no reason why we cannot agree on the last two points.” Smoothing does not necessarily resolve a conflict, but tries to convince both parties to remain at the bargaining table because a solution is possible. In smoothing, one may sacrifice one's own goals in order to satisfy the needs of the other party. Smoothing should be used:

- To reach an overarching goal

- To create obligation for a trade-off at a later date

- When the stakes are low

- When liability is limited

- To maintain harmony

- When any solution will be adequate

- To create goodwill (be magnanimous)

- When you'll lose anyway

- To gain time

This is what happens when one party tries to impose the solution on the other party. Conflict resolution works best when resolution is achieved at the lowest possible levels. The higher up the conflict goes, the greater the tendency for the conflict to be forced, with the result being a “win-lose” situation in which one party wins at the expense of the other. Forcing should be used:

- When you are right

- When a do-or-die situation exists

- When stakes are high

- When important principles are at stake

- When you are stronger (never start a battle you can't win)

- To gain status or to gain power

- In short-term, one-shot deals

- When the relationship is unimportant

- When it's understood that a game is being played

- When a quick decision must be made

Avoiding (or Withdrawing)

Avoidance is often regarded as a temporary solution to a problem. The problem and the resulting conflict can come up again and again. Some people view avoiding as cowardice and an unwillingness to be responsive to a situation. Avoiding should be used:

- When you can't win

- When the stakes are low

- When the stakes are high, but you are not ready yet

- To gain time

- To unnerve your opponent

- To preserve neutrality or reputation

- When you think the problem will go away

- When you win by delay

7.7 STUDYING TIPS FOR THE PMI® PROJECT MANAGEMENT CERTIFICATION EXAM

This section is applicable as a review of the principles to support the knowledge areas and domain groups in the PMBOK® Guide. This chapter addresses:

- Human Resources Management

- Execution

Understanding the following principles is beneficial if the reader is using this text to study for the PMP® Certification Exam:

- Components of an objective

- What is meant by a SMART criteria for an objective

- Different types of conflicts that can occur in a project environment

- Different conflict resolution modes and when each one should be used

The following multiple-choice questions will be helpful in reviewing the principles of this chapter:

- When talking about SMART objectives, the “S” stands for:

- Satisfactory

- Static

- Specific

- Standard

- When talking about SMART objectives, the “A” stands for:

- Accurate

- Acute

- Attainable

- Able

- Project managers believe that the most commonly occurring conflict is:

- Priorities

- Schedules

- Personalities

- Resources

- The conflict that generally is the most damaging to the project when it occurs is:

- Priorities

- Schedules

- Personalities

- Resources

- The most commonly preferred conflict resolution mode for project managers is:

- Compromise

- Confrontation

- Smoothing

- Withdrawal

- Which conflict resolution mode is equivalent to problem-solving?

- Compromise

- Confrontation

- Smoothing

- Withdrawal

- Which conflict resolution mode avoids a conflict temporarily rather than solving it?

- Compromise

- Confrontation

- Smoothing

- Withdrawal

ANSWERS

- C

- C

- B

- C

- B

- B

- D

PROBLEMS

7–1 Is it possible to establish formal organizational procedures (either at the project level or company-wide) for the resolution of conflicts? If a procedure is established, what can go wrong?

7–2 Under what conditions would a conflict result between members of a group over misunderstandings of each other's roles?

7–3 Is it possible to have a situation in which conflicts are not effectively controlled, and yet have a decision-making process that is not lengthy or cumbersome?

7–4 If conflicts develop into a situation where mistrust prevails, would you expect activity documentation to increase or decrease? Why?

7–5 If a situation occurs that can develop into meaningful conflict, should the project manager let the conflict continue as long as it produces beneficial contributions, or should he try to resolve it as soon as possible?

7–6 Consider the following remarks made by David L. Wilemon (“Managing Conflict in Temporary Management Situations,” Journal of Management Studies, October 1973, p. 296):

The value of the conflict produced depends upon the effectiveness of the project manager in promoting beneficial conflict while concomitantly minimizing its potential dysfunctional aspects. A good project manager needs a “sixth sense” to indicate when conflict is desirable, what kind of conflict will be useful, and how much conflict is optimal for a given situation. In the final analysis he has the sole responsibility for his project and how conflict will impact the success or failure of his project.

Based upon these remarks, would your answer to Problem 7–5 change?

7–7 Mr. X is the project manager of a $65 million project of which $1 million is subcontracted out to another company in which Mr. Y is project manager. Unfortunately, Mr. X does not consider Mr. Y as his counterpart and continually communicates with the director of engineering in Mr. Y's company. What type of conflict is that, and how should it be resolved?

7–8 Contract negotiations can easily develop into conflicts. During a disagreement, the vice president of company A ordered his director of finance, the contract negotiator, to break off contract negotiations with company B because the contract negotiator of company B did not report directly to a vice president. How can this situation be resolved?

7–9 For each part below there are two statements; one represents the traditional view and the other the project organizational view. Identify each one.

- Conflict should be avoided; conflict is part of change and is therefore inevitable.

- Conflict is the result of troublemakers and egoists; conflict is determined by the structure of the system and the relationship among components.

- Conflict may be beneficial; conflict is bad.

7–10 Using the modes for conflict resolution defined in Section 7.6, which would be strongly favorable and strongly unfavorable for resolving conflicts between:

- Project manager and his project office personnel?

- Project manager and the functional support departments?

- Project manager and his superiors?

- Project manager and other project managers?

7–11 Which influence methods should increase and which should decrease the opportunities for conflict between the following:

- Project manager and his project office personnel?

- Project manager and the functional support departments?

- Project manager and his superiors?

- Project manager and other project managers?

7–12 Would you agree or disagree with the statement that “Conflict resolution through collaboration needs trust; people must rely on one another.”

7–13 Davis and Lawrence (Matrix, © 1977. Adapted by permission of Pearson Education Inc., Upper Saddle River, New Jersey) identify several situations common to the matrix that can easily develop into conflicts. For each situation, what would be the recommended cure?

- Compatible and incompatible personnel must work together

- Power struggles break the balance of power

- Anarchy

- Groupitis (people confuse matrix behavior with group decision-making)

- A collapse during economic crunch

- Decision strangulation processes

- Forcing the matrix organization to the lower organizational levels

- Navel-gazing (spending time ironing out internal disputes instead of developing better working relationships with the customer)

7–14 Determine the best conflict resolution mode for each of the following situations:

- Two of your functional team members appear to have personality clashes and almost always assume opposite points of view during decision-making.

- R&D quality control and manufacturing operations quality control continually argue as to who should perform testing on an R&D project. R&D postulates that it's their project, and manufacturing argues that it will eventually go into production and that they wish to be involved as early as possible.

- Two functional department managers continually argue as to who should perform a certain test. You know that this situation exists, and that the department managers are trying to work it out themselves, often with great pain. However, you are not sure that they will be able to resolve the problem themselves.

7–15 Forcing a confrontation to take place assures that action will be taken. Is it possible that, by using force, a lack of trust among the participants will develop?

7–16 With regard to conflict resolution, should it matter to whom in the organization the project manager reports?

7–17 One of the most common conflicts in an organization occurs with raw materials and finished goods. Why would finance/accounting, marketing/sales, and manufacturing have disagreements?

7–18 Explain how the relative intensity of a conflict can vary as a function of:

- Getting closer to the actual constraints

- Having only two constraints instead of three (i.e., time and performance, but not cost)

- The project life cycle

- The person with whom the conflict occurs

7–19 The conflicts shown in Figure 7-1 are given relative intensities as perceived in project-driven organizations. Would this list be arranged differently for non-project-driven organizations?

7–20 Consider the responses made by the project managers in Figures 7-1 through 7-3. Which of their choices do you agree with, and which do you disagree with? Justify your answers.

7–21 As a good project manager, you try to plan for conflict avoidance. You now have a low-intensity conflict with a functional manager and, as in the past, handle the conflict with confrontation. If you knew that there would be a high-intensity conflict shortly thereafter, would you be willing to use the withdrawal mode for the low-intensity conflict in order to lay the groundwork for the high-intensity conflict?

7–22 Jones Construction Company has recently won a $120 million effort for a local company. The effort includes three separate construction projects, each one beginning at the same time. Two of the projects are eighteen months in duration and the third one is thirty months. Each project has its own project manager. How do we resolve conflicts when each project may have a different priority but they are all for the same customer?

7–23 Several years ago, Minnesota Power and Light established priorities as follows:

Level 0: no priority

Level 1: to be completed on or before a specific date

Level 2: to be completed in or before a given fiscal quarter

Level 3: to be completed within a given year

How do you feel about this system of establishing priorities?

7–24 Richard is a department manager who must supply resources to four different projects. Although each project has an established priority, the project managers continually argue that departmental resources are not being allocated effectively. Richard has decided to have a monthly group meeting with all four of the project managers and to let them determine how the resources should be allocated. Can this technique work? If so, under what conditions?

FACILITIES SCHEDULING AT MAYER MANUFACTURING

Eddie Turner was elated with the good news that he was being promoted to section supervisor in charge of scheduling all activities in the new engineering research laboratory. The new laboratory was a necessity for Mayer Manufacturing. The engineering, manufacturing, and quality control directorates were all in desperate need of a new testing facility. Upper-level management felt that this new facility would alleviate many of the problems that previously existed.

The new organizational structure (as shown in Exhibit 7-1) required a change in policy over use of the laboratory. The new section supervisor, on approval from his department manager, would have full authority for establishing priorities for the use of the new facility. The new policy change was a necessity because upper-level management felt that there would be inevitable conflict between manufacturing, engineering, and quality control.

After one month of operations, Eddie Turner was finding his job impossible, so Eddie has a meeting with Gary Whitehead, his department manager.

Eddie: “I'm having a hell of a time trying to satisfy all of the department managers. If I give engineering prime-time use of the facility, then quality control and manufacturing say that I'm playing favorites. Imagine that! Even my own people say that I'm playing favorites with other directorates. I just can't satisfy everyone.”

Gary: “Well, Eddie, you know that this problem comes with the job. You'll get the job done.”

Eddie: “The problem is that I'm a section supervisor and have to work with department managers. These department managers look down on me like I'm their servant. If I were a department manager, then they'd show me some respect. What I'm really trying to say is that I would like you to send out the weekly memos to these department managers telling them of the new priorities. They wouldn't argue with you like they do with me. I can supply you with all the necessary information. All you'll have to do is to sign your name.”

Exhibit 7-1. Mayer Manufacturing organizational structure

Gary: “Determining the priorities and scheduling the facilities is your job, not mine. This is a new position and I want you to handle it. I know you can because I selected you. I do not intend to interfere.”

During the next two weeks, the conflicts got progressively worse. Eddie felt that he was unable to cope with the situation by himself. The department managers did not respect the authority delegated to him by his superiors. For the next two weeks, Eddie sent memos to Gary in the early part of the week asking whether Gary agreed with the priority list. There was no response to the two memos. Eddie then met with Gary to discuss the deteriorating situation.

Eddie: “Gary, I've sent you two memos to see if I'm doing anything wrong in establishing the weekly priorities and schedules. Did you get my memos?”

Gary: “Yes, I received your memos. But as I told you before, I have enough problems to worry about without doing your job for you. If you can't handle the work let me know and I'll find someone who can.”

Eddie returned to his desk and contemplated his situation. Finally, he made a decision. Next week he was going to put a signature block under his for Gary to sign, with carbon copies for all division managers. “Now, let's see what happens,” remarked Eddie.

TELESTAR INTERNATIONAL*

On November 15, 1998, the Department of Energy Resources awarded Telestar a $475,000 contract for the developing and testing of two waste treatment plants. Telestar had spent the better part of the last two years developing waste treatment technology under its own R&D activities. This new contract would give Telestar the opportunity to “break into a new field”—that of waste treatment.

The contract was negotiated at a firm-fixed price. Any cost overruns would have to be incurred by Telestar. The original bid was priced out at $847,000. Telestar's management, however, wanted to win this one. The decision was made that Telestar would “buy in” at $475,000 so that they could at least get their foot into the new marketplace.

The original estimate of $847,000 was very “rough” because Telestar did not have any good man-hour standards, in the area of waste treatment, on which to base their man-hour projections. Corporate management was willing to spend up to $400,000 of their own funds in order to compensate the bid of $475,000.

By February 15, 1999, costs were increasing to such a point where overrun would be occurring well ahead of schedule. Anticipated costs to completion were now $943,000. The project manager decided to stop all activities in certain functional departments, one of which was structural analysis. The manager of the structural analysis department strongly opposed the closing out of the work order prior to the testing of the first plant's high-pressure pneumatic and electrical systems.

Structures Manager: “You're running a risk if you close out this work order. How will you know if the hardware can withstand the stresses that will be imposed during the test? After all, the test is scheduled for next month and I can probably finish the analysis by then.”

Project Manager: “I understand your concern, but I cannot risk a cost overrun. My boss expects me to do the work within cost. The plant design is similar to one that we have tested before, without any structural problems being detected. On this basis I consider your analysis unnecessary.”

Structures Manager: “Just because two plants are similar does not mean that they will be identical in performance. There can be major structural deficiencies.”

Project Manager: “I guess the risk is mine.”

Structures Manager: “Yes, but I get concerned when a failure can reflect on the integrity of my department. You know, we're performing on schedule and within the time and money budgeted. You're setting a bad example by cutting off our budget without any real justification.”

Project Manager: “I understand your concern, but we must pull out all the stops when overrun costs are inevitable.”

Structures Manager: “There's no question in my mind that this analysis should be completed. However, I'm not going to complete it on my overhead budget. I'll reassign my people tomorrow. Incidentally, you had better be careful; my people are not very happy to work for a project that can be canceled immediately. I may have trouble getting volunteers next time.”

Project Manager: “Well, I'm sure you'll be able to adequately handle any future work. I'll report to my boss that I have issued a work stoppage order to your department.”

During the next month's test, the plant exploded. Postanalysis indicated that the failure was due to a structural deficiency.

- Who is at fault?

- Should the structures manager have been dedicated enough to continue the work on his own?

- Can a functional manager, who considers his organization as strictly support, still be dedicated to total project success?

HANDLING CONFLICT IN PROJECT MANAGEMENT

The next several pages contain a six-part case study in conflict management. Read the instructions carefully on how to keep score and use the boxes in the table on page 314 as the worksheet for recording your choice and the group's choice; after the case study has been completed, your instructor will provide you with the proper grading system for recording your scores.

Part 1: Facing the Conflict

As part of his first official duties, the new department manager informs you by memo that he has changed his input and output requirements for the MIS project (on which you are the project manager) because of several complaints by his departmental employees. This is contradictory to the project plan that you developed with the previous manager and are currently working toward. The department manager states that he has already discussed this with the vice president and general manager, a man to whom both of you report, and feels that the former department manager made a poor decision and did not get sufficient input from the employees who would be using the system as to the best system specifications. You telephone him and try to convince him to hold off on his request for change until a later time, but he refuses.

Changing the input–output requirements at this point in time will require a major revision and will set back total system implementation by three weeks. This will also affect other department managers who expect to see this system operational according to the original schedule. You can explain this to your superiors, but the increased project costs will be hard to absorb. The potential cost overrun might be difficult to explain at a later date.

At this point you are somewhat unhappy with yourself at having been on the search committee that found this department manager and especially at having recommended him for this position. You know that something must be done, and the following are your alternatives:

- You can remind the department manager that you were on the search committee that recommended him and then ask him to return the favor, since he “owes you one.”

- You can tell the department manager that you will form a new search committee to replace him if he doesn't change his position.

- You can take a tranquilizer and then ask your people to try to perform the additional work within the original time and cost constraints.

- You can go to the vice president and general manager and request that the former requirements be adhered to, at least temporarily.

- You can send a memo to the department manager explaining your problem and asking him to help you find a solution.

- You can tell the department manager that your people cannot handle the request and his people will have to find alternate ways of solving their problems.

- You can send a memo to the department manager requesting an appointment, at his earliest convenience, to help you resolve your problem.

- You can go to the department manager's office later that afternoon and continue the discussion further.

- You can send the department manager a memo telling him that you have decided to use the old requirements but will honor his request at a later time.

Although other alternatives exist, assume that these are the only ones open to you at the moment. Without discussing the answer with your group, record the letter representing your choice in the appropriate space on line 1 of the worksheet under “Personal.”

As soon as all of your group have finished, discuss the problem as a group and determine that alternative that the group considers to be best. Record this answer on line 1 of the worksheet under “Group.” Allow ten minutes for this part.

Part 2: Understanding Emotions

Never having worked with this department manager before, you try to predict what his reactions will be when confronted with the problem. Obviously, he can react in a variety of ways:

- He can accept your solution in its entirety without asking any questions.

- He can discuss some sort of justification in order to defend his position.

- He can become extremely annoyed with having to discuss the problem again and demonstrate hostility.

- He can demonstrate a willingness to cooperate with you in resolving the problem.

- He can avoid making any decision at this time by withdrawing from the discussion.

In the table above are several possible statements that could be made by the department manager when confronted with the problem. Without discussion with your group, place a check mark beside the appropriate emotion that could describe this statement. When each member of the group has completed his choice, determine the group choice. Numerical values will be assigned to your choices in the discussion that follows. Do not mark the worksheet at this time. Allow ten minutes for this part.

Part 3: Establishing Communications

Unhappy over the department manager's memo and the resulting follow-up phone conversation, you decide to walk in on the department manager. You tell him that you will have a problem trying to honor his request. He tells you that he is too busy with his own problems of restructuring his department and that your schedule and cost problems are of no concern to him at this time. You storm out of his office, leaving him with the impression that his actions and remarks are not in the best interest of either the project or the company.

The department manager's actions do not, of course, appear to be those of a dedicated manager. He should be more concerned about what's in the best interest of the company. As you contemplate the situation, you wonder if you could have received a better response from him had you approached him differently. In other words, what is your best approach to opening up communications between you and the department manager? From the list of alternatives shown below, and working alone, select the alternative that best represents how you would handle this situation. When all members of the group have selected their personal choices, repeat the process and make a group choice. Record your personal and group choices on line 3 of the worksheet. Allow ten minutes for this part.

- Comply with the request and document all results so that you will be able to defend yourself at a later date in order to show that the department manager should be held accountable.

- Immediately send him a memo reiterating your position and tell him that at a later time you will reconsider his new requirements. Tell him that time is of utmost importance, and you need an immediate response if he is displeased.

- Send him a memo stating that you are holding him accountable for all cost overruns and schedule delays.

- Send him a memo stating you are considering his request and that you plan to see him again at a later date to discuss changing the requirements.

- See him as soon as possible. Tell him that he need not apologize for his remarks and actions, and that you have reconsidered your position and wish to discuss it with him.

- Delay talking to him for a few days in hopes that he will cool off sufficiently and then see him in hopes that you can reopen the discussions.

- Wait a day or so for everyone to cool off and then try to see him through an appointment; apologize for losing your temper, and ask him if he would like to help you resolve the problem.

Part 4: Conflict Resolution Modes

Having never worked with this manager before, you are unsure about which conflict resolution mode would work best. You decide to wait a few days and then set up an appointment with the department manager without stating what subject matter will be discussed. You then try to determine what conflict resolution mode appears to be dominant based on the opening remarks of the department manager. Neglecting the fact that your conversation with the department manager might already be considered as confrontation, for each statement shown below, select the conflict resolution mode that the department manager appears to prefer. After each member of the group has recorded his personal choices in the table below, determine the group choices. Numerical values will be attached to your answers at a later time. Allow ten minutes for this part.

- Withdrawal is retreating from a potential conflict.

- Smoothing is emphasizing areas of agreement and de-emphasizing areas of disagreement.

- Compromising is the willingness to give and take.

- Forcing is directing the resolution in one direction or another, a win-or-lose position.

- Confrontation is a face-to-face meeting to resolve the conflict.

Part 5: Understanding Your Choices

Assume that the department manager has refused to see you again to discuss the new requirements. Time is running out, and you would like to make a decision before the costs and schedules get out of hand. From the list below, select your personal choice and then, after each group member is finished, find a group choice.

- Disregard the new requirements, since they weren't part of the original project plan.

- Adhere to the new requirements, and absorb the increased costs and delays.

- Ask the vice president and general manager to step in and make the final decision.

- Ask the other department managers who may realize a schedule delay to try to convince this department manager to ease his request or even delay it.

Record your answer on line 5 of the worksheet. Allow five minutes for this part.

Assume that upper-level management resolves the conflict in your favor. In order to complete the original work requirements you will need support from this department manager's organization. Unfortunately, you are not sure as to which type of interpersonal influence to use. Although you are considered as an expert in your field, you fear that this manager's functional employees may have a strong allegiance to the department manager and may not want to adhere to your requests. Which of the following interpersonal influence styles would be best under the given set of conditions?

- You threaten the employees with penalty power by telling them that you will turn in a bad performance report to their department manager.

- You can use reward power and promise the employees a good evaluation, possible promotion, and increased responsibilities on your next project.

- You can continue your technique of trying to convince the functional personnel to do your bidding because you are the expert in the field.

- You can try to motivate the employees to do a good job by convincing them that the work is challenging.

- You can make sure that they understand that your authority has been delegated to you by the vice president and general manager and that they must do what you say.

- You can try to build up friendships and off-work relationships with these people and rely on referent power.

Record your personal and group choices on line 6 of the worksheet. Allow ten minutes for completion of this part.

The solution to this exercise appears in Appendix A.

*Case Study also appears at end of chapter.

1. David L. Wilemon, “Managing Conflict in Temporary Management Situations,” The Journal of Management Studies, 1973, pp. 282–296.

2. The majority of this section, including the figures, was adapted from Seminar in Project Management Workbook, © 1977 by Hans J. Thamhain. Reproduced by permission of Dr. Hans J. Thamhain.

3. See note 2.

* Revised, 2008.