chapter 10

LONG-TERM DEBT AND OTHER NON-CURRENT LIABILITIES

Long-Term Loans with Equal Blended Monthly Payments

Long-Term Loans with Monthly Payments of Interest Only

Bond Pricing in the Marketplace

Calculating Bond Interest Expense and Liability Balances

Repayment of Bonds at Maturity

Long-Term Notes or Bonds with No Explicit Interest

Defined Contribution Pension Plans

OTHER POST-EMPLOYMENT BENEFITS

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

- Calculate interest and record transactions related to long-term notes and mortgages.

- Describe the basic characteristics of bonds.

- Explain how bonds are issued and how the pricing of bonds is affected by market factors.

- Calculate a bond's selling price and prepare journal entries to record the issuance and subsequent interest payments for bonds sold at par, below par, and above par.

- Discuss the advantages and disadvantages of leasing.

- Distinguish between operating leases and capital/finance leases, and prepare journal entries for a lessee under both types of leases.

- Explain the distinguishing features of defined-contribution pension plans and defined-benefit pension plans.

- Outline the accounting issues in the reporting of pension plan liabilities.

- Describe other post-employment benefits and explain how they are treated in Canada.

- Explain why deferred/future income taxes exist, and describe how they are reported.

- Record deferred/future income taxes in simple situations.

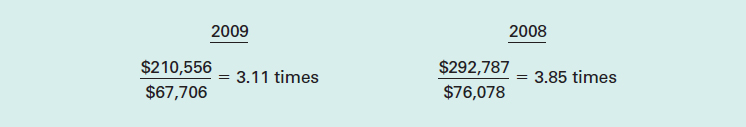

- Calculate the debt to total assets ratio and the times interest earned ratio, and comment on a company's financial health using the information from these ratios.

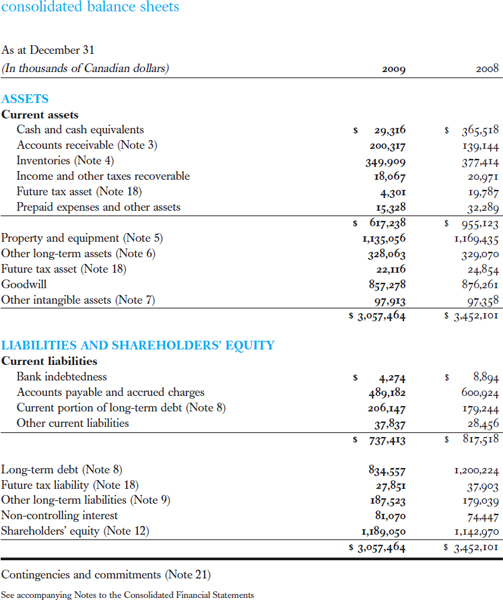

Canada Post Borrows for the Future

In early 2010, Canada Post Corporation announced plans to raise at least $1 billion in the Canadian capital markets, starting in late 2010 or early 2011. Although it has about $55 million in long-term debt, this would be the first time that the Crown corporation has taken on a significant long-term liability.

There are basically three forms of financing, explains Wayne Cheeseman, Canada Post's chief financial officer. “There's internally generated funds, the equity market, or the debt capital markets. Being a Crown corporation, the equity markets aren't open to us. We do generate funds internally, but they won't be sufficient when we look at our long-term plans. So we're looking to the debt capital markets and raising money there, obviously with a plan to pay that off over time.”

Canada Post will likely issue the debt in several tranches of $500 million per tranche over five years, says Mr. Cheeseman. At the time of writing, the corporation was in the process of selecting its financial advisors. Details like the number of units, the unit price, and coupon rate would be determined later. “Right now, we're looking at when would be an optimum time for us to go to the markets,” says Mr. Cheeseman.

The decision to raise money through debt followed Parliament's assent to a legal amendment that would increase Canada Post's borrowing limit from $300 million to $2.5 billion. “We do have to go back to the Department of Finance to get approval on the terms and conditions, but the legislative approval is in place,” says Mr. Cheeseman.

The money raised will be used primarily for Canada Post's Postal Transformation Initiative currently underway. “The Postal Transformation Initiative involves redoing and upgrading our physical and technological platform,” says Mr. Cheeseman. The corporation is working to modernize its operations with several capital projects planned over several years, including new and renovated buildings and updated equipment and systems. The initiative includes building a new processing plant in Winnipeg; replacing part of its current fleet with fuel-efficient, low-emission vehicles; and implementing new sorting equipment in its plants. Once the initiative is completed, the company will have a much greater ability to track and trace parcels, and more accurate address management systems.

“We basically have two goals—to provide an acceptable level of service to all Canadians while remaining financially self-sufficient,” says Mr. Cheeseman. These improvements are expected to save Canada Post approximately $250 million a year. “With the cost savings, we're going to take advantage of the coming attrition in the business. It won't be a situation where people lose their jobs. It's simply as they retire, we won't replace a number of people.”

With these long-term plans, Canada Post hopes to remain viable and relevant in Canada's rapidly changing and technologically advancing society.

Businesses often use long-term debt or the issuance of new shares as a means of raising outside capital that they can then use to finance growth. By using the new cash to buy long-term assets or invest in other companies, they can improve or expand their existing operations or enter new markets. In the opening story, Canada Post decided to use long-term debt to acquire the funds it needs in order to buy capital assets that will improve its operating efficiency.1 The story mentions that Canada Post is staggering the debt by issuing it in tranches. French for “slices,” the term “tranches” refers to portions of the total amount. This allows the corporation to borrow the funds only as it needs them, thus minimizing its interest charges.

Long-term debt is usually preferable to short-term debt for financing the acquisition of long-term assets, because both the benefits from the expansion efforts and the payments on the debt will be spread over a long period of time. The cash generated from the growth can then be used to repay the debt.

As you will see later in this chapter, companies are usually able to borrow at an interest rate that is lower than the rate of return they will earn from the income-generating activities that the borrowed money will be used for. This phenomenon is called financial leverage, and can be used to increase the rate of return earned by the shareholders.

Sometimes new debt is simply used to pay off old debt, which is referred to as re-financing or rollover of debt. When short-term debt is repaid with the proceeds from long-term debt, a company is able to spread out its debt payments over a longer time period, which means that there is less pressure on short-term cash needs.

USER RELEVANCE

Users of financial statement information need to pay particular attention to the type and extent of debt in a company. All debt must be repaid at some time. In addition to the principal amount, there is usually a requirement to make periodic interest payments. In terms of a company's “cost of capital” (a topic that is studied in finance courses), issuing debt is cheaper than issuing shares. It also does not dilute the current shareholders' ownership interests, as would an issuance of more shares. However, a company cannot rely too extensively on debt for financing: debt involves risks, and stakeholders become concerned if the proportion of debt to equity financing gets too high. When the level of debt is high, lenders demand higher interest rates to compensate for the increased risks.

As a user of financial statements, you should find answers to the following questions when evaluating a company's debt:

- What are the maturity dates and interest rates on the debt? Knowing this will enable you to determine the amount and timing of the future cash flows that will be necessary to meet the debt obligations.

- Are there any special conditions attached to the debt? For example, is the company required to maintain a certain debt/equity ratio or level of retained earnings? Failure to meet debt conditions (called covenants) could make the debt become due immediately, which could have very serious consequences for the business.

- What is the proportion of debt to equity financing? The higher the amount of debt to equity, the greater the risk that the company may have difficulty meeting the debt requirements. Not only could a high proportion of debt to equity result in higher interest rates being charged to the company, it could also make lenders reluctant to extend further credit to the company, which may affect its future financial viability.

- Is the organization using leverage to the advantage of its shareholders? In other words, is it earning a rate of return on its investment that is higher than the cost of the debt? As a user, you will want to examine the company's financial statements to see if leverage is being used effectively.

In this chapter, we are going to illustrate some of the most common non-current liabilities, including long-term loans, bonds payable, lease liabilities, pension and other post-employment benefit liabilities, and deferred income taxes. The general nature of liabilities was discussed in Chapter 9, along with the recognition and valuation criteria for liabilities. You might want to refresh your memory before moving on.

LONG-TERM NOTES AND MORTGAGES

When a company chooses to use long-term debt financing, it can go to various sources to obtain the funds, including the commercial paper market. “Commercial paper” is a promissory note that is sold to another business. In effect, one company (the issuer of the note) borrows funds directly from another (the buyer of the note). However, the commercial paper market is generally used only by large companies that have high credit ratings. More commonly, companies borrow from commercial banks or other financial institutions, much as individuals borrow money to buy a new home or car. These borrowings are often listed on a company's financial statements as long-term notes payable, loans payable, or mortgages.

All types of long-term debt are usually accompanied by a formal agreement between the borrower and the lender that specifies the terms of the loan (such as the interest rate, payment dates, and duration of the loan). In addition, the loan agreement often specifies certain conditions that the borrower must meet during the loan period. These conditions or restrictions on the company are known as covenants. The covenants may limit the company's freedom to borrow additional amounts, to sell or acquire assets, or to pay dividends. The restrictions specified in the covenants are intended to protect the lender against the borrower defaulting on the loan.

The accounting for long-term notes payable is much the same as for short-term notes, which was discussed and illustrated in Chapter 9. Long-term borrowings almost always have explicit interest charges, and in most cases these are paid periodically during the life of the loan. However, even if the interest is not explicitly stated or is paid only at maturity, interest expense should be recognized over the life of the loan.

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 1

Calculate interest and record transactions related to long-term notes and mortgages.

Long-Term Loans with Equal Blended Monthly Payments

A mortgage loan is simply a long-term debt with a capital asset—such as a building or piece of equipment—pledged as collateral or security for the loan. If the borrower fails to repay the loan according to the specified terms, the lender has the legal right to have the asset seized and sold, and the proceeds from the sale applied to the repayment of the debt.

Mortgages are usually instalment loans. As discussed in Chapter 9, this means that payments are made periodically rather than only at the end of the loan. Also, the periodic payments are usually blended payments, consisting of both interest and principal components. The total amount of the payment is the same each period, but the portion of each payment that is consumed by interest is reduced as the principal balance is reduced.

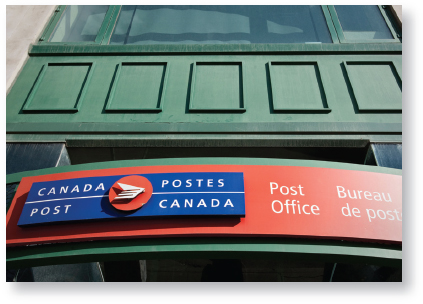

To illustrate this, we will consider the case of a company that takes out a three-year, $100,000 mortgage on September 30. The interest rate on the loan is 6% per year, and equal blended payments of $3,042.19 are to be made at the end of each month. (This amount can be calculated using the interest tables provided on the inside covers of the book. Simply divide the $100,000 principal, or present value, by the present value factor for an annuity of 36 periods [3 years × 12 months per year = 36 months] at an interest rate of 0.5% per period [6% per year ÷ 12 months per year = 0.5% per month]: $100,000 ÷ 32.87102 = $3,042.19. Alternatively, the monthly payments required to repay the loan can be calculated using the payment function in a financial calculator or computer spreadsheet, such as Excel. Simply enter 0.005 for the interest rate per period, 36 for the number of periods, and 100,000 for the principal or present value. This will return a result of 3,042.19 for the payment.)

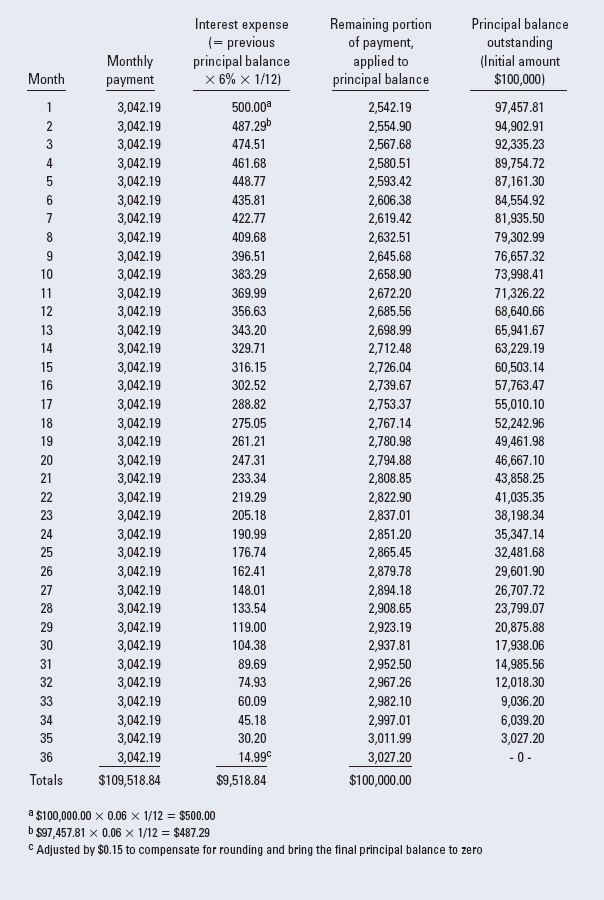

Exhibit 10-1 presents a loan amortization table for this mortgage, showing how the first portion of each of the payments is allocated to the monthly interest charge, with the remaining portion being applied to reduce the principal balance of the loan.

Notice that $500 of the first payment is consumed by interest and only $2,542 is left to be applied to the reduction of the principal. By contrast, only $15 of the last payment is consumed by interest, leaving $3,027 to be applied to the reduction of the principal.

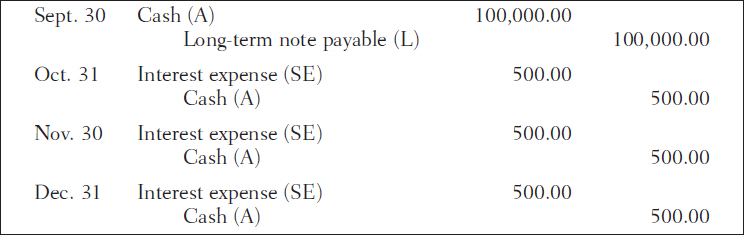

The journal entries to record the initial borrowing and the first three payments on the mortgage are as follows:

Long-Term Loans with Monthly Payments of Interest Only

To illustrate a different type of loan arrangement, we will now consider the case of a company that takes out a three-year loan for $100,000 at 6% on September 30, with terms that specify that only the interest on the loan is to be paid each month; the principal is to be repaid as a lump sum when the note matures at the end of the three-year period.

EXHIBIT 10-1 LOAN AMORTIZATION TABLE

For a three-year, 6% mortgage of $100,000 with payments made at the end of each month

Note the key difference between this situation and the previous one: in this case, there are no reductions in the principal of the loan during its life. In this type of situation a loan amortization table is not necessary, since the principal balance remains the same from the inception of the loan until it is repaid in full at maturity. Consequently, the amount of interest remains the same each month: $100,000 × 6% × 1/12 = $500.

The journal entries to record the initial borrowing and the first three interest payments on the note are as follows:

We chose to use the account title “Long-term note payable” for this liability. However, alternatives such as “Long-term bank loan” are also commonly used.

EARNINGS MANAGEMENT

Debt covenants usually include financial measures or tests, such as ratios, that the borrowers must satisfy; otherwise, the debt will become due and payable on demand. As a result, restrictive covenants can create environments that encourage bias in accounting and financial reporting. That is, debt covenants may put so much pressure on companies to achieve the required minimums and pass the tests that managers engage in aggressive accounting and business practices to satisfy the covenants.

Users of financial statements should therefore be aware of the existence and nature of key debt covenants, and alert to the potential for manipulation of the financial statements to satisfy them.

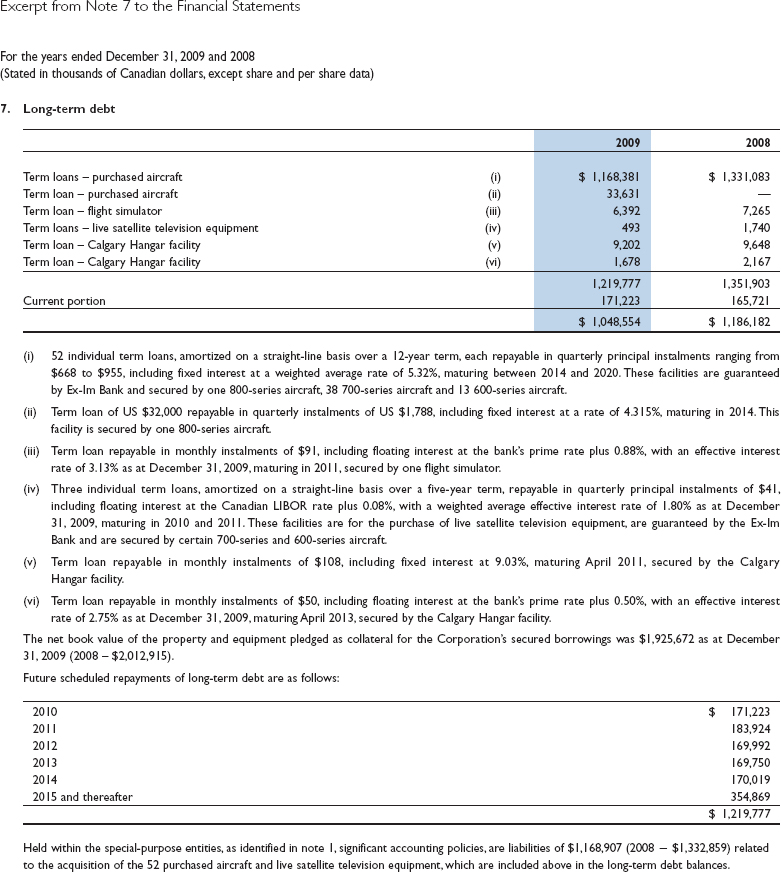

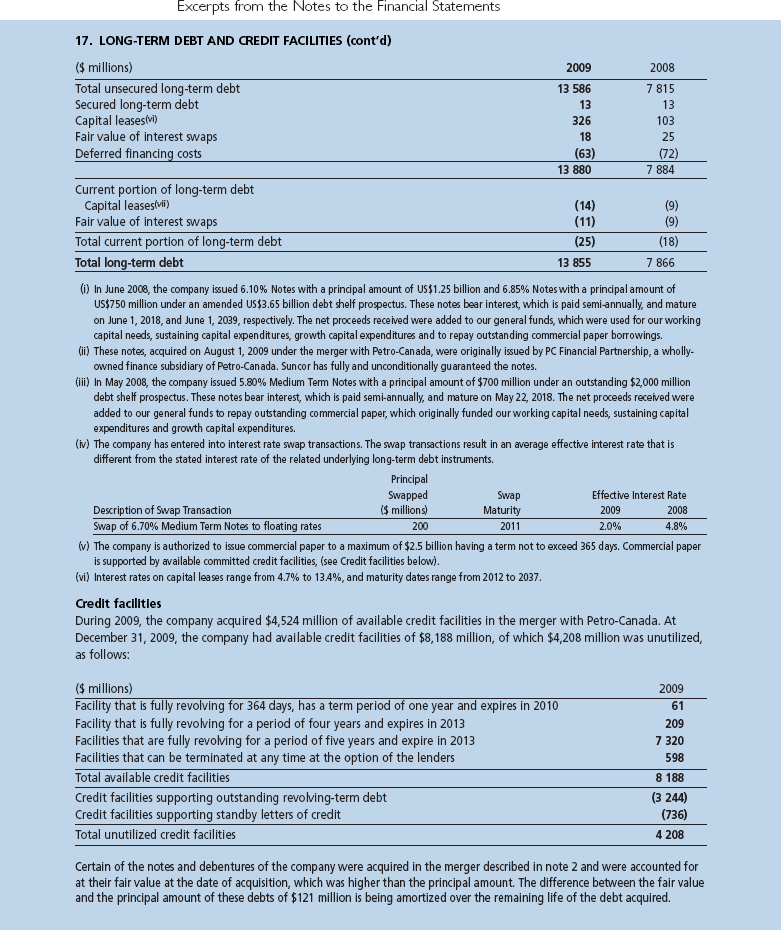

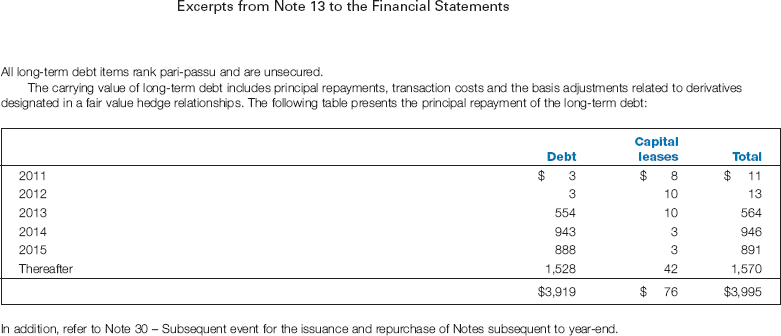

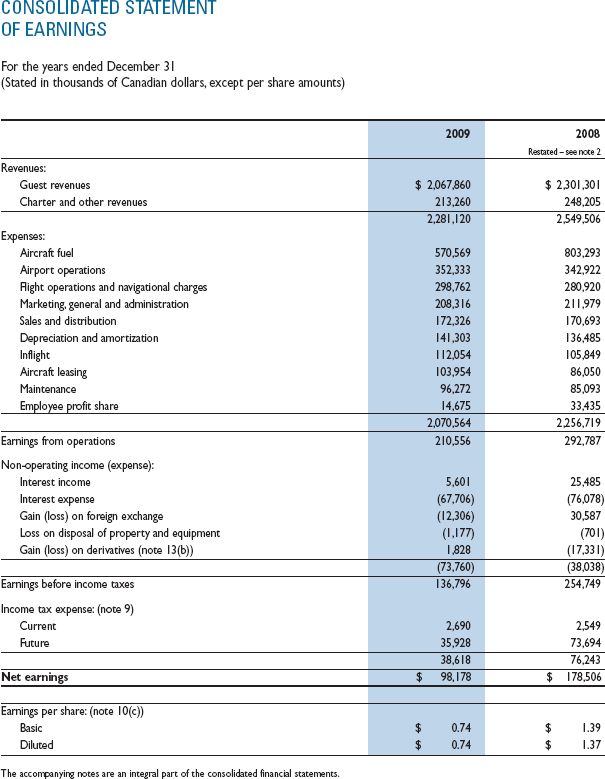

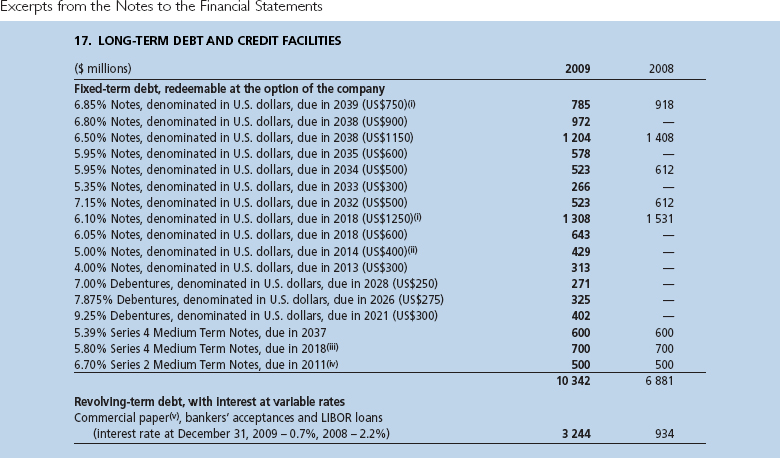

Exhibit 10-2 is an excerpt from the notes to the 2009 financial statements of West Jet Airlines Inc., describing the various components of long-term debt outstanding. Notice that the term loans consist of blended payments of interest and principal, payable monthly or quarterly, and each loan is secured by a specific piece or type of equipment. For 2009, the total amount of property and equipment pledged as security is $1,925,672 thousand. The interest rates vary by loan, depending on when the loans were taken out, and some loans have fixed interest rates while others have floating rates. The last part of the note indicates the loan repayments required over the next five years and the total amount due after that.

BONDS AND DEBENTURES

When a large company wants to borrow long-term funds to support its operations, it does not always have to take a loan from a specific lender such as a bank or other financial institution. Instead, it can get the funds from “the market” by issuing bonds.

EXHIBIT 10-2 WEST JET AIRLINES INC. 2009 ANNUAL REPORT

WEST JET AIRLINES INC. 2009 ANNUAL REPORT

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 2

Describe the basic characteristics of bonds.

Basic Bond Characteristics

A bond is a formal agreement between a borrower (the company that issues the bonds) and the lenders (the investors who buy the bonds) that specifies how the borrower is to pay back the lenders, as well as any conditions that the borrower must meet while the bonds are outstanding. The bond's terms, conditions, restrictions, and covenants are usually stated in a document called an indenture agreement.

Bonds that are traded in public markets are fairly standardized. The indenture agreement will state a face value or principal amount for the bonds, which is usually $1,000 per bond. The face value specifies the cash payment that the borrower will make to the lenders at the bond's maturity date. In addition to the cash payment at maturity, most bonds also include semi-annual interest payments to the lenders. The amount of these payments is determined by multiplying the bond interest rate by the face value and dividing by two (because the interest payments are semi-annual). The bond interest rate is stated as an annual percentage and is usually not the effective or true interest rate, but simply a rate that determines the periodic amount of the interest payments.

Another important item in the indenture agreement is the collateral (if any) that the company pledges as security to the lenders. If collateral is pledged, it means that, if the company defaults on either the interest payments or the maturity payment, the bondholders can force the pledged assets to be sold in order to settle the debt. A “mortgage bond” has real property (fixed assets) pledged as collateral. A collateral trust bond usually has shares and bonds of other companies pledged as collateral.

A bond that carries no specific collateral but is backed by the company's general creditworthiness is known as a debenture bond, or simply a debenture. Debenture bonds can be either senior or subordinated debentures. The distinction between senior and subordinated is the order in which the investors (creditors) are paid in the event of bankruptcy: senior creditors are paid before subordinate claims.

Some indenture agreements specify special provisions that are designed to make the bonds more attractive to investors. Convertible bonds, for example, can be exchanged for or converted to a specified number of common shares in the company issuing them.

Sometimes bonds are sold directly to investors through what is referred to as a “private placement”. These types of bonds do not trade in public markets. Private placements are usually made to institutional investors, such as the trustees in charge of large pension funds.

Generally, bonds are sold initially to institutional and individual investors through an investment banker. The investment banker sells the bonds to its clients before the bonds are traded in the open market, and gets a commission for handling the transaction. The investment banker first consults with the company about its objectives, and helps design an issue that will both meet the company's objectives and attract investors. All the bond features that have been discussed in the previous sections will be considered when structuring the offering.

The investment banker is responsible for the initial sale of the issue to its clients. Because most issues involve larger amounts than one investment banker can easily sell, the investment banker usually forms a syndicate with other investment bankers, who will be jointly responsible for selling the issue. The syndicate members are sometimes known as the underwriters of the issue.

Once the bonds have been sold by the investment bankers, they can be freely traded between investors in the bond market—much as shares are traded on the stock market. At this point, any investors can buy or sell the bonds. The prices of the bonds will then fluctuate according to the forces of supply and demand, and with changes in economic conditions.

accounting in the news

Bonds Yield Sweet Returns

UK chocolatier Hotel Chocolat is raising funds in a unique way, by issuing bonds that will pay out in chocolate rather than money. Members of Hotel Chocolat's Tasting Club have been offered two investment options: a three-year £2,000 ($3,030 CAD) bond, for which they will receive a box of chocolates valued at £18 ($27 CAD) every two weeks (equivalent to a 6.7% yield); or a three-year £4,000 ($6,058 CAD) bond that will pay out the equivalent of a 7.3% yield in chocolate. Although the company will be paying yields that are higher than standard bond rates, the cost of making the boxes of chocolates is much less than their market value. With 100,000 Tasting Club members, who already pay for discounts, special offers, and regular home deliveries of chocolate samples, Hotel Chocolat hopes to raise £5 million ($7.5 million CAD) through the bond issue. The transaction is an alternative to bank loan financing, since its size is too small for a typical bond issue. The company has appointed BDO as its advisor and has received approval from the UK Financial Services Authority. It plans to use the funds raised to expand its chain of retail outlets, develop a new plantation in St. Lucia, and expand its business overseas.

Sources: Natalie Harrison, “Candy Bond Investors Get Paid in Chocolate,” Reuters, May 24, 2010; Jason Hesse, “Hotel Chocolat Offers a Sweet Deal to Chocoholics,” Real Business—The Champion of UK Enterprise, http://realbusiness.co.uk/sales_and_marketing/hotel_chocolat_offers_a_sweet_deal_to_chocoholics

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 3

Explain how bonds are issued and how the pricing of bonds is affected by market factors.

Bond Pricing in the Marketplace

Bond prices are established in the marketplace by the economic forces of supply (from companies wanting to sell bonds) and demand (from investors wanting to buy them). The buyers determine what the cash flows are going to be for the bonds—both in the periodic interest payments and the eventual repayment of the principal amount—and the rate of return they want to earn, based on the risk of potential default by the company. They then use these amounts to calculate the present value of the cash flows they will receive from the bonds, to determine the amount they are willing to pay for them.

The process of calculating the present value of bonds involves discounting (at the desired earnings rate) the future cash flows from the bonds (periodic interest payments and repayment of principal). Potential buyers determine the yield (or desired rate of return) by looking at the interest rates that could be earned from alternative investments and the relative risk of the particular bond issue. The higher the level of risk, the higher the yield rate has to be. In other words, for buyers to accept a higher risk of default, they have to be compensated for that risk with a higher rate of return. Buyers also have to factor in any special features of the bonds, such as if they are convertible into shares. However, to keep things as simple as possible in the rest of this section, these special features will be ignored as we discuss bond pricing.

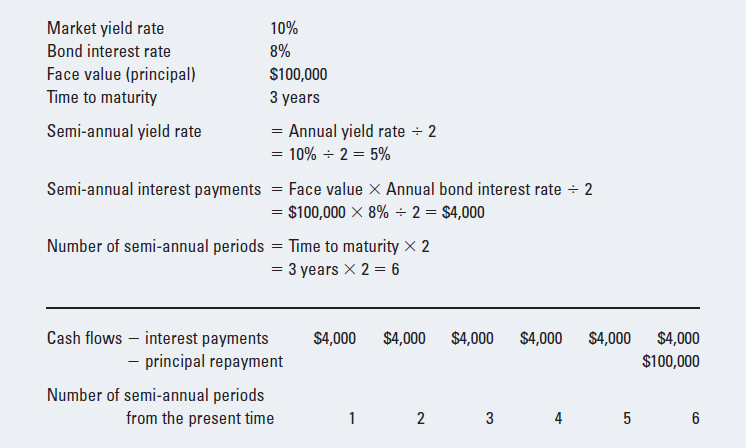

The starting point in determining a bond's value is to calculate the cash flows that will be received by the buyer (and paid by the seller). To illustrate the calculation of interest payments and bond values, we will use the following example.

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 4

Calculate a bond's selling price and prepare journal entries to record the issuance and subsequent interest payments for bonds sold at par, below par, and above par.

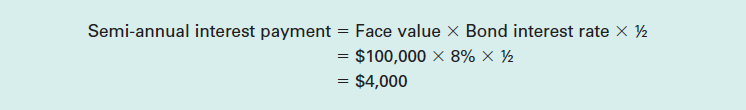

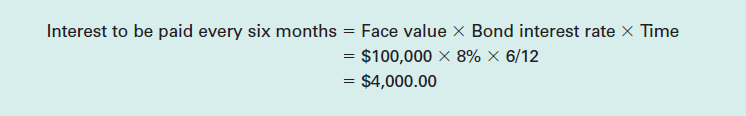

Baum Company issues bonds on December 31, 2011, with a total face value of $100,000, a bond interest rate of 8%, and a maturity date of December 31, 2014. The company must make a $100,000 payment to the lenders on December 31, 2014, and must make interest payments every six months of $4,000 each. The $4,000 amount is calculated as follows:

The bond interest rate is sometimes referred to as the coupon rate, stated rate, or nominal rate. All of these terms refer to the rate of interest that is specified in the bond contract and is used to calculate the interest payments.

There will be a total of six interest payments, because there are three years to maturity and two interest payments per year. The interest payments on a bond are typically structured to come at the end of each six-month period. The stream of interest payments is called an annuity in arrears, meaning that it is a series of equal payments that are made at the end of each period.

Although these bonds have a face value of $100,000, they may sell for more or less than this amount. Bond selling prices are determined by competitive forces in the bond market, because there are always many other bonds that investors could purchase. If a particular bond issue looks attractive, in comparison to bonds of similar duration and risk, investors will be willing to pay a premium price (i.e., more than the face value) to purchase them. On the other hand, if the terms are unattractive in comparison to bonds of similar duration and risk, investors will only be willing to purchase the bonds if they can do so at a discounted price (i.e., less than their face value).

Case 1: The bond interest rate is lower than the required yield

To illustrate this, suppose that when Baum issues its bonds the competitive interest rate in the market for bonds of similar duration and risk is 10%, compounded semi-annually. This competitive market rate of interest is often called the yield or effective interest rate. Since investors could buy other, similar bonds and earn a rate of return of 10%, they will not buy Baum's bonds unless they can earn the same rate of return or yield.

HELPFUL HINT

There are many terms for interest rates in the context of bonds:

- The interest rate to determine the interest payments is referred to as the bond rate, the coupon rate, the stated rate, the nominal rate, or the contract rate.

- The interest rate to determine the selling price of the bonds and the interest expense is referred to as the market rate, the effective rate, or the yield.

To determine exactly how much they are willing to pay for Baum's bonds, investors look at the cash flows that Baum will pay them, and then discount these cash flows using the yield rate of 10%. Exhibit 10-3 shows the timeline and the cash flows for this bond.

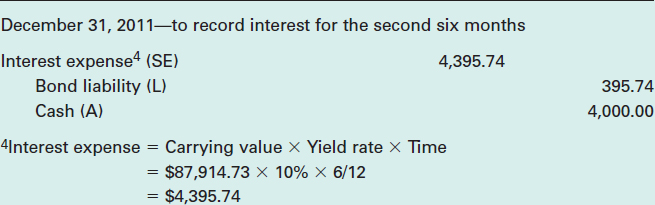

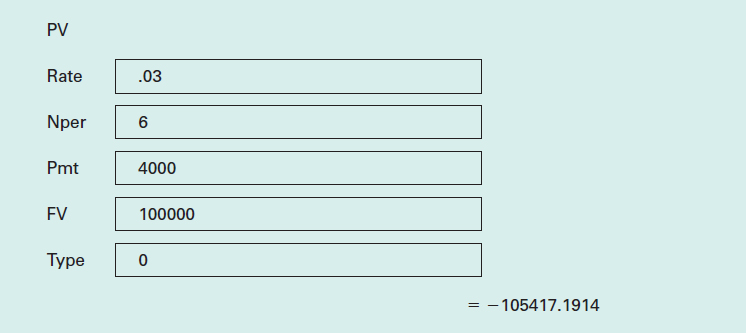

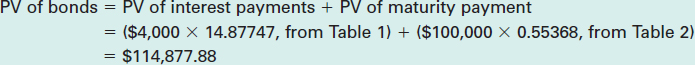

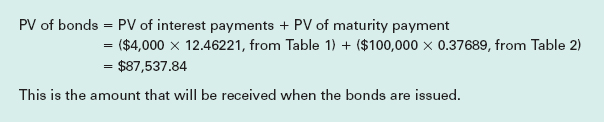

Note that the interest payments (the six payments of $4,000 each) are an annuity in arrears and that the maturity payment ($100,000) is a lump-sum cash flow at the end of the sixth period. There are six periods because interest payments are made twice each year. The bonds' issuance price will be determined by calculating the present value of these cash flows, based on the 5% semi-annual yield or effective rate of interest.

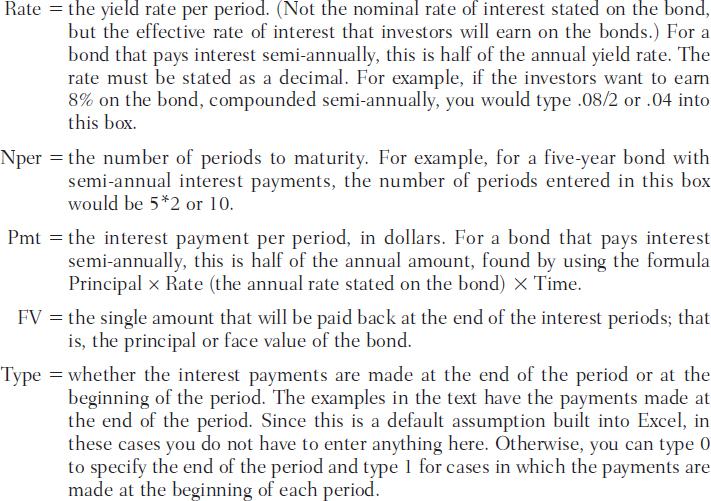

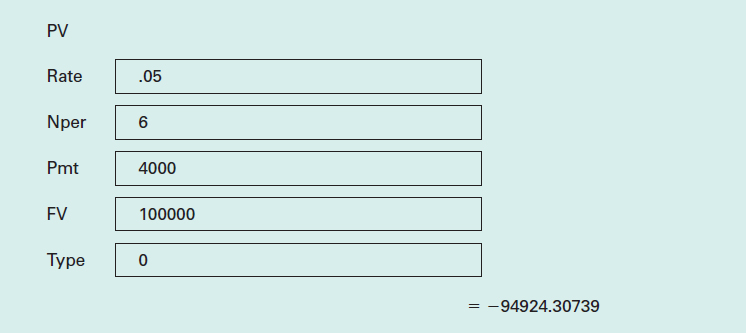

To calculate the present value of the bonds' future cash flows, we will use the Time Value of Money tables located on the inside covers. Alternatively, the appendix on pages 680–682 shows how the PV (present value) function in Microsoft® Excel can be used to calculate these amounts. These calculations can also be done using a financial calculator that has present value functions. To find out how to calculate these amounts on a financial calculator, go to the Study Tools section on the student website at http://www.wiley.com/hoskin.

EXHIBIT 10-3 BAUM COMPANY BONDS

Study Tools

The two Time Value of Money tables printed on the inside covers contain pre-calculated factors for various combinations of interest rates and time periods. The present value of the cash flows is determined by multiplying the cash flow amounts by the appropriate factors from the tables. The factors in these tables are sometimes referred to as discount factors, and the results are referred to as discounted cash flows.

Notice that the heading on Table 1 is “Present Value Factors for an Annuity in Arrears.” Since an annuity is a series of equal payments, Table 1 will be used for the interest payments. By contrast, the heading on Table 2 is “Present Value Factors for a Lump-Sum Payment.” Since the principal is repaid only once, as a lump sum when the bonds mature, Table 2 will be used for the principal payment.

To calculate the present value of Baum's bonds, we first need to multiply the amount of the interest payments by the factor from Table 1 for an annuity of 6 periods (since there are 6 interest payments) discounted at an interest rate of 5% (the market rate of interest for each six-month period). Looking in Table 1, where the row for 6 periods intersects with the column for 5%, you will see that the appropriate present value factor is 5.07569. Multiplying the amount of the interest payments ($4,000) by this factor gives $20,302.76. This is the present value of a series of 6 semiannual future payments of $4,000 each, when the competitive rate of return is 5% per period. This is the amount that investors will be willing to pay now, to receive these interest payments in the future.

Next, we need to multiply the amount of the principal payment by the factor from Table 2 for a lump-sum payment to be made after 6 periods, discounted at the same interest rate of 5% (the yield or market rate). Looking in Table 2, where the row for 6 periods intersects with the column for 5%, you should find the present value factor 0.74622. Multiplying the amount of the principal payment ($100,000) by this factor gives $74,622.00. This is the present value of a future payment of $100,000 after 6 semi-annual periods, when the competitive rate of return is 5% per period. This is the amount that investors will be willing to pay now, to receive this principal payment in the future.

The total present value of the bonds is the sum of these two amounts: $20,302.76 (for the interest) + $74,622.00 (for the principal) = $94,924.76. This is the amount that investors will pay for Baum's bonds. Notice that it is less than the $100,000 face value of the bonds. This is because these bonds pay interest of only 8% (4% semiannually), while the market rate of interest is 10% (5% semi-annually). Since Baum's bonds pay less interest than comparable bonds from other companies, investors will not be willing to pay full price for them.

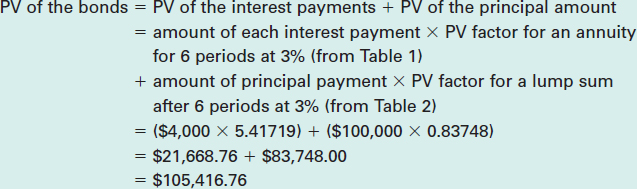

Case 2: The bond interest rate is higher than the required yield

How does a different required rate of return or yield affect the value of the bonds? Suppose that instead of 10% the competitive rate of interest in the market for this type of bond is 6%. The only thing that will change in the calculation is the present value factors that are used, as the following shows:

Present value of the Baum Company bonds if the market rate of interest is 6% (3% per semi-annual period):

Notice that this is more than the $100,000 face value of the bonds. This is because these bonds pay interest of 8% (4% semi-annually), while the market rate of interest is only 6% (3% semi-annually). Since, under this scenario, Baum's bonds pay more interest than comparable bonds from other companies, investors will be willing to pay extra for them.

In bond pricing terminology, when bonds are sold for more than their face value they are said to be sold at a premium. When bonds are sold for less than their face value, they are said to be sold at a discount. If they are sold for exactly their face value, they are said to be sold at par. You should avoid placing any connotations on the words “premium” and “discount.” They do not mean either that the buyers paid too much or that they got a good deal. In competitive financial markets, the amount that investors pay—whether it is premium, discount, or par value—is always the appropriate price for the bond, given the yield or market rate for similar bonds.

Case 3: The bond interest rate is the same as the required yield

What yield rate would have to be used in the example for the bonds to be issued at par? The answer is 8%, because in this case the required yield or market interest rate is the same as the bond interest rate. Whenever the interest rate paid by bonds is exactly equal to the required yield or market rate, the bonds will sell at par. When the bond interest rate is lower than the market rate, the bonds will not be very attractive compared to alternative investments and will therefore sell at a discount. On the other hand, when the bond interest rate is higher than the market rate, the bonds will be relatively attractive and will therefore sell at a premium. This should seem logical to you, if you think of it from a buyer's point of view.

You may be wondering why a company would issue (sell) its bonds at other than their par value. Companies generally try to set the interest rate on their bonds to be close to the interest rate that the market will demand (i.e., at what they expect the competitive rate of interest to be). However, when a company decides to issue bonds as a way of raising capital, it is usually a long process. It must first get financial advice and legal advice on aspects of the indenture agreement, and then get the necessary approvals and have the bond certificates printed and ready for issue. By the time the bonds are actually issued to investors, the market's assessment of the company's risk may have changed, and/or general economic conditions may have changed. In such cases, the bond interest rate will differ from the market rate and, as a result, the bonds will sell at a discount or a premium rather than at their par value.

A final point to note about bond pricing terminology is that bond prices are typically expressed out of 100. For example, a $1,000 bond selling for $949 is said to be selling at 94.9, meaning 94.9% of its face value. Similarly, a $1,000 bond selling for $1,054 is said to be selling at 105.4, representing 105.4% of its face value, and a bond selling for its par value is said to be selling at 100.

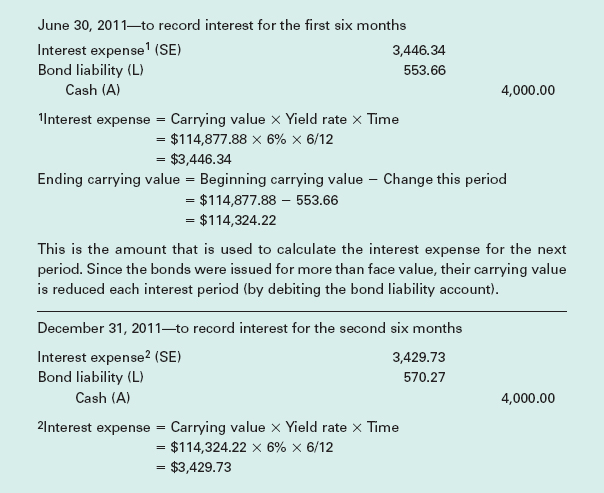

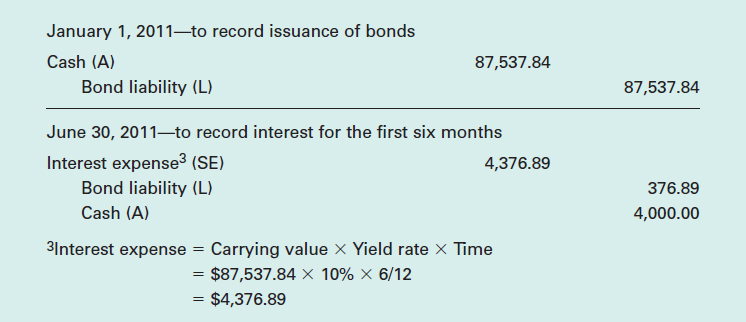

Calculating Bond Interest Expense and Liability Balances

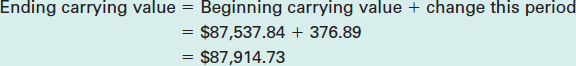

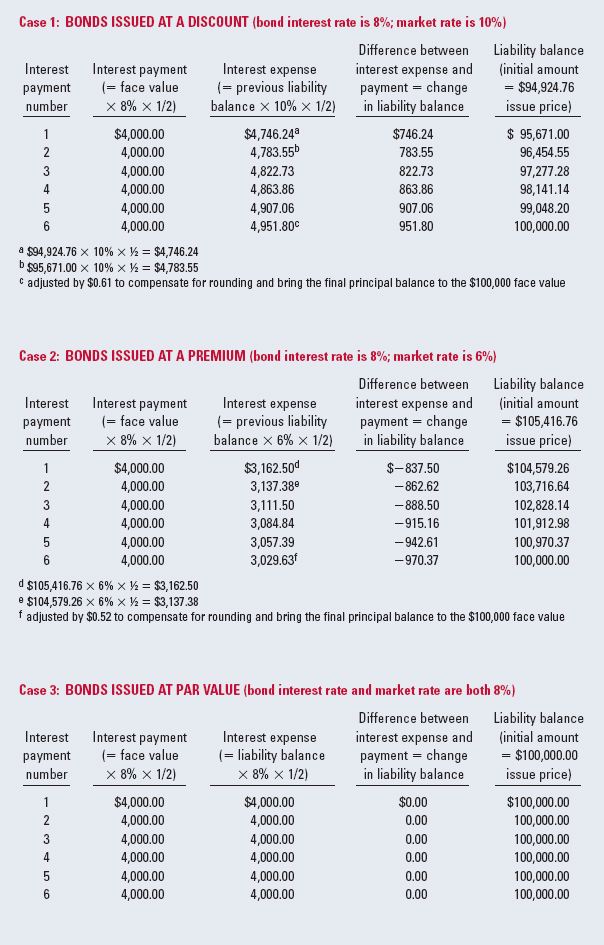

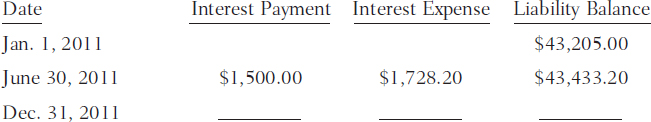

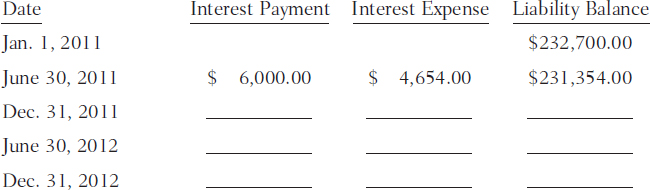

Exhibit 10-4 presents amortization tables for the Baum Company bonds, under the three scenarios discussed above. These have been prepared in the same way as the amortization tables for various loans, notes, and mortgages presented in Chapter 9 and earlier in this chapter.

In each case, the interest payment is calculated using the face value and the bond interest rate, while the interest expense is calculated using the liability balance and the yield or market rate.

Notice that when the bonds are issued at a discount, the liability balance starts at less than the face value and increases over the life of the bonds, until it equals the face value when the bonds are due for repayment. Conversely, when the bonds are issued at a premium, the bond liability starts at more than the face value and decreases as each interest payment is made, until it equals the face value when the bonds mature. When the bonds are issued at their par value, the liability balance is the same as the face value over the entire life of the bonds. In each case, the final bond liability equals the principal amount to be repaid when the bonds are due for repayment.

EXHIBIT 10-4 BOND AMORTIZATION TABLES FOR THE BAUM COMPANY EXAMPLE

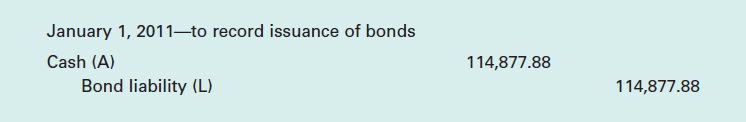

Accounting for Bonds

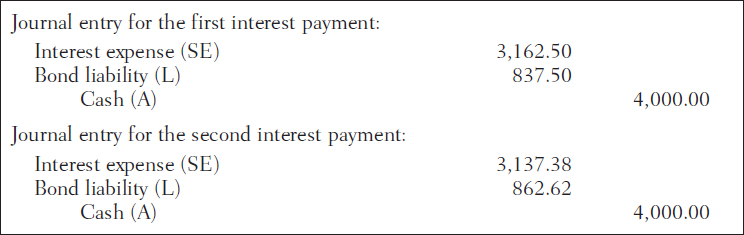

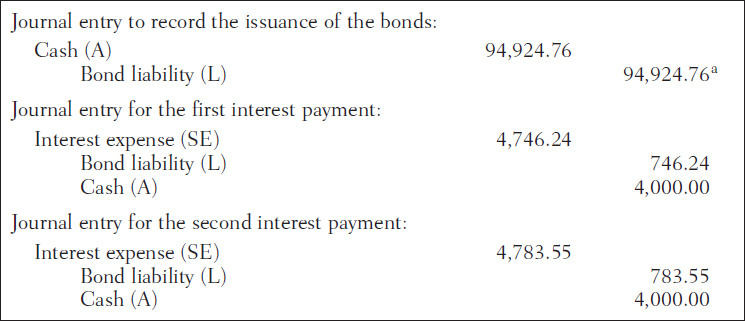

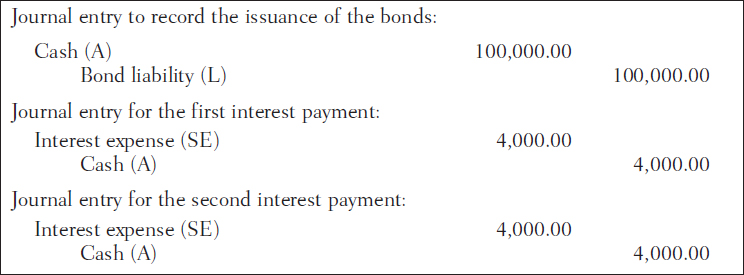

Continuing with the Baum Company example, we now illustrate the journal entries for bond accounting. The entries to record the issuance of the bonds and the first two interest payments are shown below, for each of the three scenarios developed earlier (issued at a discount, at a premium, and at par). For the interest entries, the amounts are taken from the amortization tables in Exhibit 10-4.

Case 1: Bonds issued at a discount

HELPFUL HINT

When calculating bond interest, remember the following:

- The interest payment is calculated using the values specified in the bond contract: the bond interest rate and the face value of the bonds. Since these are both constants, the interest payment is a constant amount—the same for each semiannual interest period throughout the life of the bonds.

- The interest expense is calculated using the yield or market rate of interest at the time the bonds were issued (the same rate used in the present value calculations that determine the selling price) and the previous liability balance. For bonds issued at a discount or a premium, the liability balance changes each period and the interest expense is therefore a different amount each period.

Notice that when bonds are issued at a discount there is a difference between the amount of interest expense and the amount of interest paid in cash, and this difference increases the liability balance over the life of the bonds. This is done each interest period, and results in the bond liability at the maturity date equalling the face value of the bonds. Increasing the bond liability is necessary because, when the bonds mature, the company has to repay the full face value of the bonds ($100,000), not just the amount ($94,924.76) that was received when the bonds were issued.

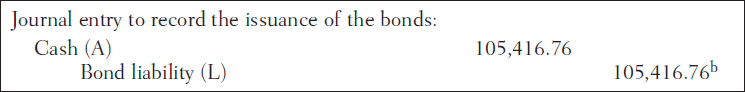

Case 2: Bonds issued at a premium

a Traditionally, accountants would have recorded this in two parts: a $100,000.00 credit to Bonds Payable, partially offset by a $5,075.24 debit to a contra-liability account called Discount on Bonds Payable. For the statement of financial position, the contra-liability for the discount on the bonds would be deducted from the bonds payable account, to show the net liability of $94,924.76. As each interest payment was recorded, a portion of the discount would be amortized as interest expense.

Since using a Discount on Bonds Payable account makes the accounting procedures significantly more complex, does not affect the final outcome, and is not encouraged under International Financial Reporting Standards, we use the much simpler approach illustrated above.

bTraditionally, accountants would have recorded this in two parts: a $100,000.00 credit to Bonds Payable and a $5,416.76 credit to an adjunct liability account called Premium on Bonds Payable. For the statement of financial position, the adjunct liability for the premium on the bonds would be added to the bonds payable account, to show the total liability of $105,416.76. As each interest payment was recorded, a portion of the premium would be amortized against interest expense.

Since using a Premium on Bonds Payable account makes the accounting procedures significantly more complex, does not affect the final outcome, and is not encouraged under International Financial Reporting Standards, we use the simpler approach illustrated above.

Notice that when the bonds are issued at a premium the difference between the amount of interest expense and the amount of interest paid in cash decreases the liability balance over the life of the bonds. This will result in the bond liability at the maturity date equalling the face value of the bonds. This is logical, because the company will have to repay only the $100,000 face value of the bonds at maturity, not the $105,416.76 that was received when they were issued.

Case 3: Bonds issued at par value

Repayment of Bonds at Maturity

As shown in Exhibit 10-4, whether bonds are issued at a discount, at a premium, or at par, when they reach their maturity date the liability balance equals the face value. Consequently, the journal entry to record the retirement or repayment of the bonds is the same in all three cases. For the Baum Company bonds, the entry is as follows:

![]()

Early Retirement of Debt

Although a company does not have to pay off its debts until they mature, there are times when it makes sense to pay a debt earlier. This transaction is known as early retirement, or early extinguishment, of debt.

Some bonds may have a “call feature” that allows the issuing company to buy them back at a predetermined price before they mature. These are referred to as callable bonds. Otherwise, bonds can be retired before maturity by simply buying them in the bond market. Whether they are called or purchased in the open market, it is likely that the bond liability or carrying value of the bonds will be different from the amount paid to retire them. Consequently, a gain or loss will usually arise when debt is retired early.

To demonstrate the accounting for an early retirement of debt, suppose the Baum Company bonds were called or bought back after two years for a price of $101,000.

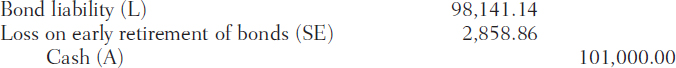

For case 1, where the bonds were issued at a discount, Exhibit 10-4 shows that the bond liability after two years (i.e., after four interest payments) is $98,141.14. Since the company pays $101,000 to retire a debt that is on the books at only $98,141.14, it records a loss for the difference. The journal entry to record the early retirement of the bonds in this case is as follows:

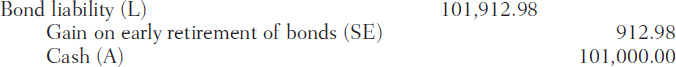

For case 2, where the bonds were issued at a premium, Exhibit 10-4 shows that the bond liability after two years is $101,912.98. Since the company pays only $101,000 to retire a debt that is on the books at $101,912.98, it records a gain equal to the difference. The journal entry to record the early retirement of the bonds in this case is as follows:

This case illustrates one reason why a company may decide to retire its debt early: if the cost to retire the debt is lower than the amount of the bond liability on the books, a gain will be recorded. The downside of this, however, is that if the company needs to raise more capital through the use of debt, it may have to pay a higher interest rate for the new debt. If so, the one-time gain on the retirement of the debt in the current period could be offset by ongoing higher interest costs in future periods. Under these circumstances, the company may not really be better off (as suggested by the gain) for having retired its old debt.

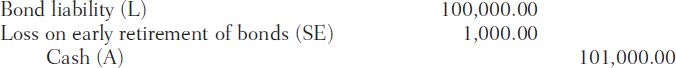

For case 3, where the bonds were issued at par value, Exhibit 10-4 shows that the bond liability after two years (or at any point during the life of the bonds) is $100,000. Since $101,000 is paid to retire a debt that is on the books at only $100,000, a loss is recognized for the difference. The journal entry to record the early retirement of the bonds in this case is as follows:

EARNINGS MANAGEMENT

The early retirement of debt is a discretionary action by management, and one which can often result in significant gains or losses being reported on the statement of earnings. Users of financial statements should therefore be aware that managers may be tempted to manipulate the financial statements through early debt retirements, and should critically evaluate management's reasoning and the economic justification for any early retirement of debt.

Long-Term Notes or Bonds with No Explicit Interest

Sometimes bonds or long-term notes are issued with no provision for interest on them. This is most commonly done in financing arrangements for the purchase of long-term assets. For example, suppose a company negotiates the purchase of some equipment for $100,000, which is to be paid at the end of three years with no interest added. In this situation, accounting principles would say that the appropriate value for recording this equipment and the related note payable is whatever it would have cost the company to purchase the equipment in cash paid immediately. The true value of the asset is not the $100,000 that will be paid in three years, because surely the equipment could have been acquired for less if the company had purchased it for cash. Similarly, the initial amount of the liability should not be recorded as $100,000, because logically—given the time value of money—the company could settle the debt now for less than the $100,000 that it has agreed to pay after three years.

We can determine the appropriate value for recording the equipment and the related note payable by calculating the present value of the $100,000 that is to be paid at the end of three years, using an appropriate interest rate. For example, if the company would normally have been charged an interest rate of 6% annually for a three-year loan, the discounting factor that should be used is 0.83962 (the PV factor for 3 periods at 6%, from Table 2). The present value of this transaction is $100,000 × 0.83962 = $83,962, and the journal entries to record it are as follows.

To record the acquisition of the asset and the issuance of the note:

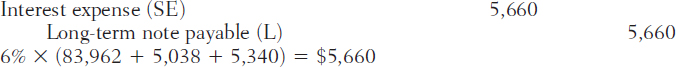

To accrue interest for the first year:

To accrue interest for the second year:

To accrue interest for the third year:

To record the payment of the note:

![]()

Note that interest expense is recognized—even though none is explicitly charged—and over the life of the note the liability balance is increased to the amount that is due on its maturity date (i.e., $83,962 + $5,038 + $5,340 + $5,660 = $100,000).

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 5

Discuss the advantages and disadvantages of leasing.

LEASES

When a company needs to use an asset such as a piece of machinery, there are two ways it can obtain the use of the asset. One is to purchase it outright. A second is to enter into a lease agreement in which another company (the lessor) provides the asset and the company that wants to use it (the lessee) makes periodic payments to the lessor in exchange for use of the asset over the length of the lease agreement (the lease term). There are benefits and costs to both alternatives.

One benefit of purchasing the asset and thereby owning it is that the company can depreciate the asset for tax purposes and, in some cases, obtain an investment tax credit for the purchase. Investment tax credits are incentives provided by the Canada Revenue Agency to encourage investment in certain types of assets. These credits usually take the form of a direct reduction in the company's tax bill, based on a percentage of the asset's cost.

A disadvantage of purchasing the asset is that it ties up capital that could have been used for other purposes. Also, if the company has to borrow to buy the asset, the company's debt ratios and interest coverage ratios will change, which could affect its future borrowing capabilities. (These ratios are discussed later in this chapter, and in Chapter 12.)

Realizing a gain from appreciation in the asset's value is another potential benefit of ownership. Of course, the downside is incurring a loss from the asset's decline in value, which could be dramatic if the asset becomes technologically obsolete or loses its market popularity.

On the other hand, leasing often offers several benefits. The main advantage is that it often provides a low-cost form of financing. This is largely due to the fact that the lessor typically has higher taxable income than the lessee and therefore gets larger tax savings from the capital cost allowance deduction, enabling it to offer attractive terms to the lessee.

Another advantage of leasing is that the lessee does not have to put up its own capital to acquire the asset. It also does not have to borrow to buy the asset, which may mean that its debt and interest coverage ratios will not be affected.

A final advantage of leasing is that, because the lessee does not own the asset, the risk of loss from obsolescence usually falls on the lessor. A related advantage is that the lessee may not want to use the asset for its full useful life. If the company wants to use the asset for only a limited period, there is significantly less risk associated with the residual value if the company leases the asset rather than buying it.

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 6

Distinguish between operating leases and capital/finance leases, and prepare journal entries for a lessee under both types of leases.

Classification of Leases

The accounting issues for a lessee are best illustrated using two extreme examples. At one extreme, suppose that the lease contract is signed for a relatively short period of time, say two years, whereas the leased asset's useful life is eight years. In this case, it is clear that the lessee is not buying the asset, but is instead renting it for only a short period. The lease contract is a mutually unexecuted rental contract, and the cash payments required by the lease are recorded by the lessee as simply rent expense and an outflow of cash. This type of lease is known as an operating lease.

Suppose at the other extreme that the lease contract is signed for the asset's entire useful life and that the title to the asset passes to the lessee at the end of the lease term (which is fairly common, in long lease contracts). In this case, the substance of the transaction is that the lessee has, in effect, bought the asset and agreed to pay for it in instalments, in the form of lease payments. There is essentially no difference between this arrangement and one in which the lessee takes out a long-term loan, uses the funds to buy the asset for cash, and then repays the loan in instalments. The lender, in this case, is the lessor. It seems appropriate for the lessee to account for this as a long-term borrowing and a purchase of a long-term asset. The asset is therefore recorded at its cost (measured as the present value of the lease payments), and is depreciated in the same way that a purchased capital asset would be. The account name for the asset often includes reference to the lease aspect (for example, leased equipment or equipment under lease). The obligation to the lessor is recorded as a non-current liability, and interest expense is recognized over the term of the lease. This type of lease has traditionally been known as a capital lease, but under International Financial Reporting Standards is called a finance lease.

Although the appropriate accounting procedures for these extreme situations seem fairly clear, the following question arises: What does the company do when the lease is somewhere in between these extremes? To address this issue, criteria have been developed to distinguish capital/finance leases from operating leases. From the lessee's point of view, the lease qualifies as a capital/finance lease if any of the following criteria are met:

CRITERIA FOR A CAPITAL/FINANCE LEASE

- The lease transfers ownership of the asset to the lessee by the end of the lease term.

Rationale: If the lessee will own the asset at the end of the lease, it is buying the asset; the lease is merely a financing arrangement. - The lessee has an option to purchase the asset at a price that is much lower than its fair value, and it is reasonably certain that this “bargain purchase option” will be exercised.

Rationale: If the lessee is likely to buy the asset at the end of the lease, because it can do so at a bargain price, it is ultimately buying the asset. - The lease term is for the major part of the asset's economic life.

Rationale: If the lessee will have the use of the asset during most of its useful life, it should treat the transaction as if, in substance, it is buying the asset. - The present value of the minimum lease payments is equal to substantially all of the fair value of the asset.

Rationale: If the value being paid to lease the asset is close to the cost of buying it, the lessee should treat the transaction as if, in substance, it is buying the asset. - The leased asset is of such a specialized nature that, without major modifications, only the lessee can use it.

Rationale: If the asset would not be of use to anyone else, then it is reasonable to treat it as an asset that is being sold by the lessor and bought by the lessee.

The underlying spirit of these criteria is that, if the lease arrangement substantially transfers the risks and rewards of ownership of the asset to the lessee, it should be classified as a capital/finance lease and treated as an acquisition of a capital asset and a long-term liability.

In terms of the financial statement effects, companies generally have a strong preference for treating leases as operating leases. This keeps the lease obligations off the statement of financial position (creating a situation often referred to as “off-balance-sheet” financing), and there is therefore no effect on the debt to total assets ratio, the debt to equity ratio, or the interest coverage ratios. However, a lease can be treated as an operating lease only if the transaction does not meet any of the above criteria.3

IFRS INSIGHTS

The criteria for classifying leases under International Financial Reporting Standards are less specific than under former Canadian GAAP. They are therefore more open to interpretation, and will require accountants and auditors to exercise more judgement.

For example, Canadian GAAP previously specified that if the lease term was 75% or more of the economic life of the asset, the lease was classified as a capital (finance) lease. By contrast, the comparable IFRS criterion states that if the lease term covers the major part of the economic life of the asset, the lease must be classified as a finance lease. It does not state whether the major part means 60%, 75%, or maybe 90%.

Similarly, Canadian GAAP previously specified that if the present value of the lease payments was 90% or more of the fair value of the asset, the lease was classified as a capital (finance) lease. The comparable IFRS criterion does not specify a percentage. Instead, it states that if the present value of the minimum lease payments is equal to substantially all of the fair value of the asset, the lease must be classified as a finance lease.

Accounting for Leases

To illustrate the differences in accounting under a capital/finance lease and an operating lease, we will consider the following simple situation. Suppose that equipment is leased for three years and requires monthly lease payments of $1,000, payable at the end of each month.4 The implicit interest rate in the lease contract is 12%.

If the lease qualifies as an operating lease, the only entry would be to record the payments as rent or lease expense each period. The following entry would be made at the beginning of each month.

MONTHLY JOURNAL ENTRY FOR AN OPERATING LEASE

![]()

Note that when a lease is treated as an operating lease, the lessee records neither an asset nor a liability—even though it has exclusive use of the asset for the three-year term of the lease, and it is contractually committed to make payments for the duration of the lease.

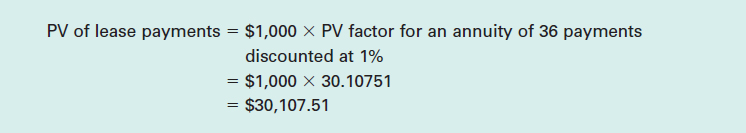

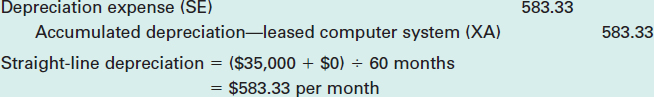

If the lease qualifies as a capital/finance lease, the transaction must be recorded as the purchase of an asset and a related long-term financing obligation. Both the asset and the obligation would initially be recorded at the present value of the lease payments. In our example, the interest rate per period for use in discounting the future cash flows would be 1% (i.e., the 12% annual rate ÷ 12 months per year). Because the payments are made monthly and the lease term is three years, there would be a total of 36 payments.

Using Table 1 for the present value of an annuity (on the inside covers), the present value of the lease is calculated as follows:

The entry to record the acquisition of the asset and the related lease liability at the outset of the lease is as follows:

INITIAL JOURNAL ENTRY FOR A CAPITAL/FINANCE LEASE

![]()

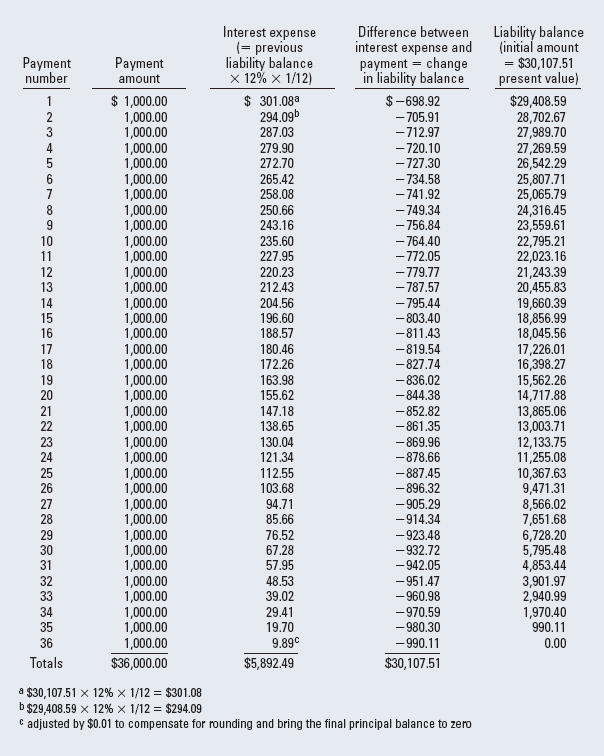

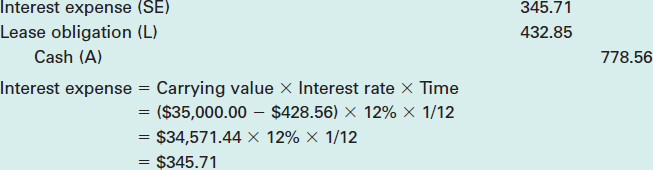

The lease obligation will result in the recognition of interest expense, similar to that generated by a long-term note payable. To highlight the similarities, an amortization table for the lease liability is presented in Exhibit 10-5.

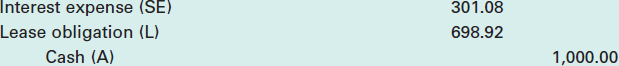

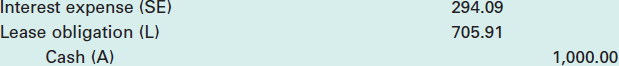

The journal entries to record the first two monthly payments are as follows:

CAPITAL/FINANCE LEASE PAYMENT ENTRIES

At the end of the first month:

At the end of the second month:

EXHIBIT 10-5 AMORTIZATION TABLE FOR LEASE LIABILITY

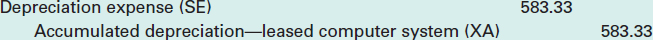

In addition, because the leased asset is being treated as if it had been purchased, the equipment must be depreciated. If title to the asset passes to the lessee at the end of the lease, the depreciation will be calculated in the usual way: the asset's useful life will be its physical life, and the residual value (if any) will be deducted. Otherwise, if title does not pass to the lessee at the end of the lease, the useful life of the asset will be limited to the term of the lease—since the company will not be able to use the asset after the lease ends—and any residual value will be irrelevant, because the lessee company will not get the residual value.

In this case, since there is no indication that title to the equipment passes to the lessee at the end of the lease, its useful life (for the lessee) will be equal to the lease term. Also, because the equipment will be returned to the lessor at the end of the lease, there will be no residual value (for the lessee); it must depreciate the entire value of the leased equipment.

If the company uses straight-line depreciation, the monthly depreciation will be $30,107.51 ÷ 36 months = $836.32, and the entry to record it will be as follows:

CAPITAL/FINANCE LEASE DEPRECIATION ENTRY

At the end of each month:

![]()

The impact of a lease transaction on the financial statements depends on its classification. On the statement of financial position, if the lease arrangement qualifies as a finance lease, both the company's assets and its liabilities will be higher than under an operating lease. On the statement of earnings, the company will report both depreciation expense and interest expense under a finance lease, compared to only equipment rental or lease expense under an operating lease.

In our example, if the lease is classified as a finance lease, the depreciation plus interest expense for the first month will be $836.32 + $301.08 = $1,137.40. By contrast, if the lease is classified as an operating lease, the expense will be $1,000. In the first month, therefore, classification as a finance lease results in higher expenses (and these would be even higher if the company used an accelerated method of depreciation).

The total expenses reported over the entire life of the lease will be the same, however, regardless of which method is used to record the lease transaction. If it is treated as an operating lease, the total expense will be $36,000 (36 payments of $1,000 each). If it is treated as a finance lease, the total expenses will also be $36,000 (consisting of $30,107.51 in depreciation and $5,892.49 in interest expense). The difference, then, is in the pattern of expense recognition over the life of the lease. Operating leases show the same amount of expense each period, while finance leases show more expense in the early periods (when interest charges, and perhaps depreciation, are high) and less expense in later periods.

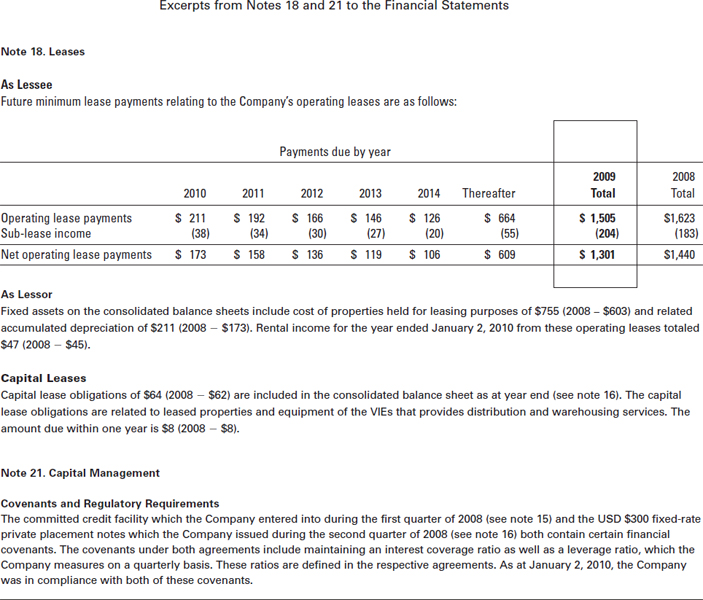

Although no asset or liability is recorded under operating leases, companies with significant operating leases have to disclose their commitments to pay for these leases—as discussed in Chapter 9. Companies are required to disclose the future lease payments to be made in total and for each of the next five years. Finance lease obligations also require similar disclosures. The future payment obligations associated with leases would typically be shown in a note that relates either to long-term debt or to commitments.

accounting in the news

Lease Fights Prevent Hamilton Hockey Score

Although lease arrangements have several benefits for the lessee, the binding terms of the contract can be problematic—even in the hard-hitting world of the National Hockey League.

One of the main reasons cited for the failure of the 2007 bid by Research In Motion founder, Jim Balsillie, to bring the Nashville Predators to Hamilton, Ontario, was disputes regarding the Predators' arena lease. The NHL said the lease precluded approval of relocation and the league would only consider relocation as part of a sale in cases where a lease was expiring or could be broken unilaterally.

Even when the team filed for bankruptcy in May 2009, the City of Glendale, Arizona—which was then the home to the Predators franchise—objected to any relocation. Balsillie tendered an offer to buy the team after it filed for bankruptcy, still with the goal of moving it to Hamilton, where his experience with leases has been more positive. Indeed, the City of Hamilton voted unanimously to approve a 20-year arena lease agreement with Balsillie for the renovation and use of Copps Coliseum—but only if he eventually succeeds in bringing the hockey team there.

Sources: David Naylor, “Never in Hamilton,” Globe and Mail, July 14, 2007; Sean Fitz-Gerald, “Balsillie Gets Copps Coliseum Lease as Battle Looms, National Post, May 13, 2009.

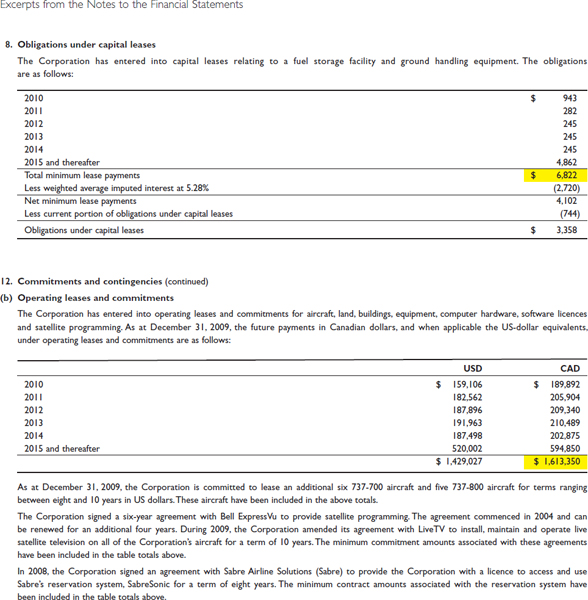

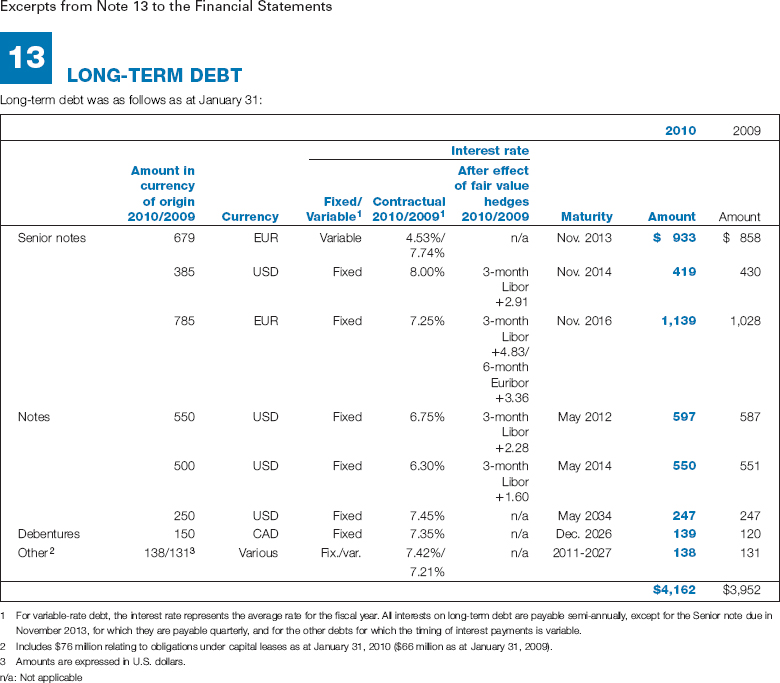

Like many airlines, WestJet Airlines Ltd. leases some of its aircraft, as well as other assets such as land, buildings, and equipment. In WestJet's financial statements, the required disclosures are found in Note 12 for the operating leases and Note 8 for the finance (capital) leases. Excerpts from these notes are presented in Exhibit 10-6.

Notice that the overwhelming majority of WestJet's leases are operating leases rather than finance or capital leases. In fact, the total amount of payments due under its operating leases ($1,613,350 thousand CAD) is over 200 times the total due under its capital leases ($6,822 thousand).

IFRS INSIGHTS

The International Accounting Standards Board has been considering changes to lease accounting that, if adopted as IFRS, could have a significant impact on how leases are accounted for. It seems quite likely that a different accounting model will be adopted, and that the present requirements and practices in accounting for leasing arrangements will no longer apply.

PENSIONS

Pensions are agreements between employers and employees that provide the latter with benefits (income) upon retirement. To the extent that the company is obliged to make payments under these agreements, their costs should be recorded in the years when the company receives the benefits from the work of its employees. In other words, to be in accordance with the matching principle, pension costs should be recognized when the employees earn their pensions, not when they receive them. Two kinds of pension plans are commonly used by employers: defined contribution plans and defined benefit plans.

EXHIBIT 10-6 WESTJET AIRLINES INC. 2009 ANNUAL REPORT

EXHIBIT 10-6 WESTJET AIRLINES INC. 2009 ANNUAL REPORT

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 7

Explain the distinguishing features of defined-contribution pension plans and defined-benefit pension plans.

Defined Contribution Pension Plans

In a defined contribution pension plan, the employer agrees to make a specified (or defined) contribution to a retirement fund for the employees. The amount is usually set as a percentage of the employees' salaries. Employees sometimes make their own contributions to the same fund, to add to the amounts invested. The amount of the pension benefits that will be paid to the employees in their retirement depends on how well the investments in the retirement fund perform. The employer satisfies its obligation to the employees when it makes the specified payments into the fund. The fund is usually managed by a trustee (someone outside the company's employ and control), and the assets are legally separated from the company's other assets, which means they are not reported on the company's statement of financial position.

The accounting for defined contribution funds is straightforward. The company accrues the amount of its obligation to the pension fund, and then records a payment. Because the liability is settled, no other recognition is necessary in the financial statements. The entries to recognize the pension expense and the related payment are as follows:

Companies generally make cash payments that coincide with the accruals, because they cannot deduct the cost for tax purposes if the cash payment is not made. Therefore, with a defined contribution pension plan there is usually no liability balance to report.

Defined Benefit Pension Plans

A defined benefit pension plan is more complex. It guarantees to pay the employees a certain amount of money during each year of their retirement. The formula used to calculate how much will be paid usually takes into consideration how long an employee has worked for the company as well as the highest salary (or an average of the highest salaries) that the employee earned while working for the company. For example, a plan might specify that the employee will receive 2% of the average of the highest three years of salaries, multiplied by the number of years that the employee worked for the company. If the employee worked for the company for 30 years and had an average salary of $60,000 for the highest three years, the annual pension benefit would be $36,000 per year (2% × $60,000 × 30 years).

Of course, employees may leave the company at some point prior to their retirement. If the pension benefits belong to employees only as long as they work there, then there may be no obligation on the company's part to pay out pension benefits. In most plans, however, there is a provision for vesting the benefits. Benefits that are vested belong to the employees, even if they leave the company.

Because the payments to retired employees will occur many years in the future, pensions represent an estimated future obligation. In estimating the cost of the future obligation today (i.e., the liability's present value), several estimations and projections must be made. These include the length of time the employee will work for the company, the age at which the employee will retire, the employee's average salary during the highest salary years, and the number of years the employee will live after retiring. All these factors will affect the amount and timing of the future cash flows (pension payments). For companies with many employees, the total obligation of the pension plan usually has to be estimated based on the characteristics of the average employee rather than of particular employees. In addition, the company must choose an appropriate interest rate to use for calculating the present value of the future pension payments.

Each year, as employees work for the company, they earn pension benefits that oblige the company to make cash payments at some point in the future. Calculating the present value of the future pension obligation generally requires the services of an actuary. The actuary is trained in the use of statistical procedures to make the types of estimates required for pension calculations.

The accounting entries for defined benefit pension plans are essentially the same as the preceding entry for defined contribution plans. The company must accrue the expense and the related obligation to provide pension benefits. The amounts are difficult to estimate in the case of defined benefit plans, but the concept is the same as for defined contribution plans. The entry made to recognize the pension expense is called the accrual entry. Setting aside cash to pay for these future benefits is done by making a cash entry, which is sometimes called the funding entry. Many employee pension plan agreements have clauses that require the company to fund the pension obligation (i.e., to set aside funds to cover the liability). However, because of the uncertainties associated with the liability amounts, some companies have been reluctant to fully fund their pension obligations.

There is no accounting requirement that the amount expensed be the same as the amount funded. Therefore, the amount of pension expense that is recognized often differs from the amount of cash that is transferred to the trustee in a particular period. A net pension obligation will result if more is expensed than funded, or a net pension asset will exist if the funding is larger than the amount expensed. The calculation of the pension expense to be recorded each period involves many complex factors, and is beyond the scope of this book.

Pension funds are described as overfunded if the value of the pension fund assets held by the trustee exceeds the present value of the future pension obligations. In under-funded pension plans, the value of the pension fund assets is less than the present value of the future pension obligations. Pension plans in which the fund assets equal the present value of the future obligations are called fully funded. The pension fund itself is usually handled by a trustee, and contributions to the fund cannot be returned to the employer except under extraordinary circumstances. To provide sufficient funds to pay the pension benefits, the trustee invests the cash that is transferred to the fund. The trustee then pays benefits to the retired employees out of the pension fund assets.

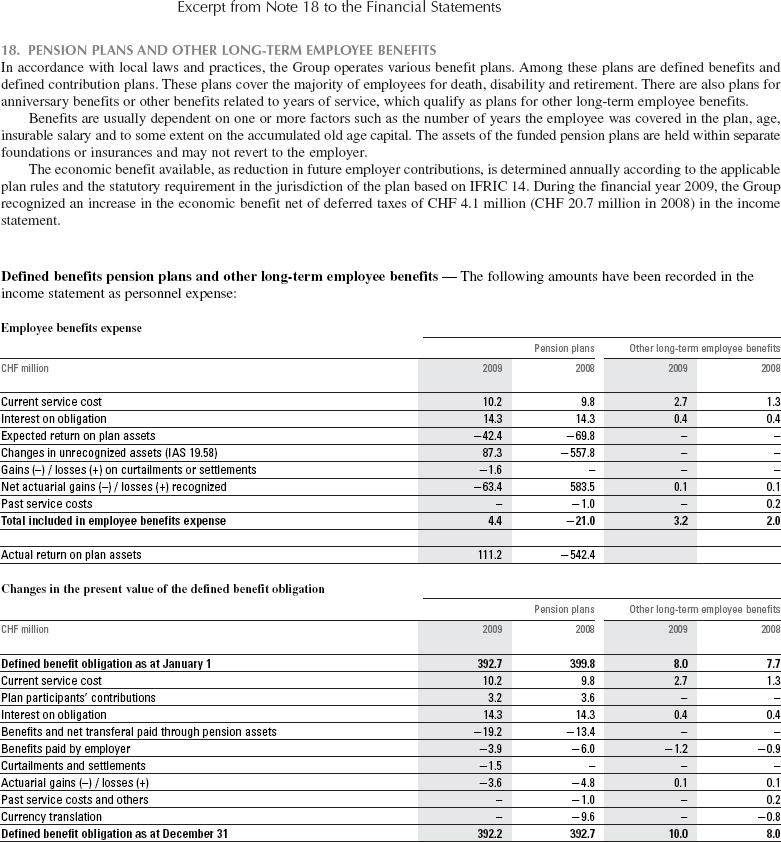

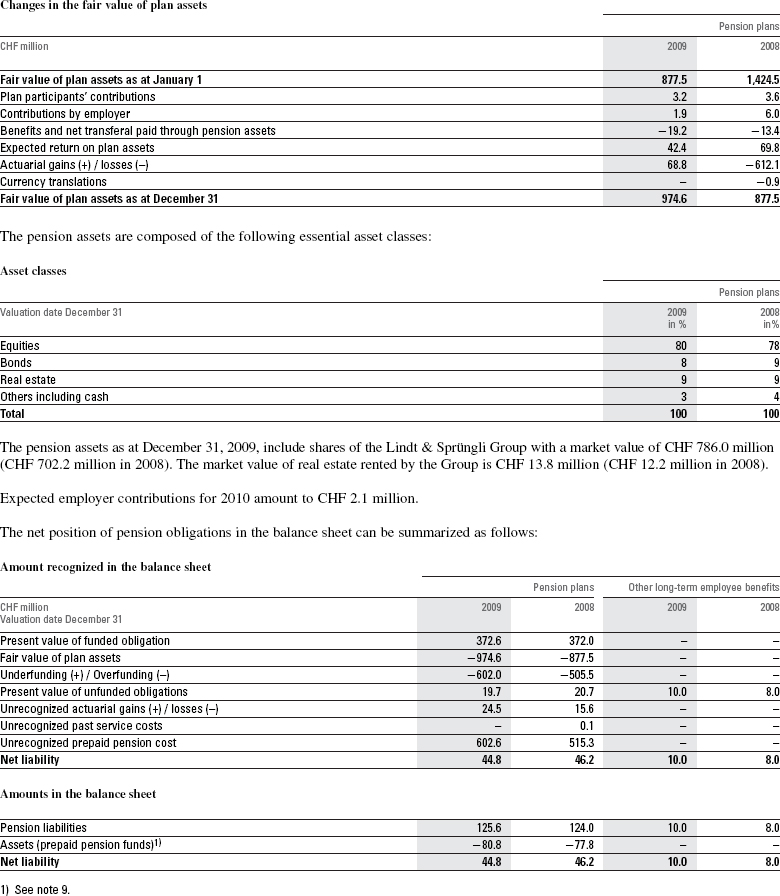

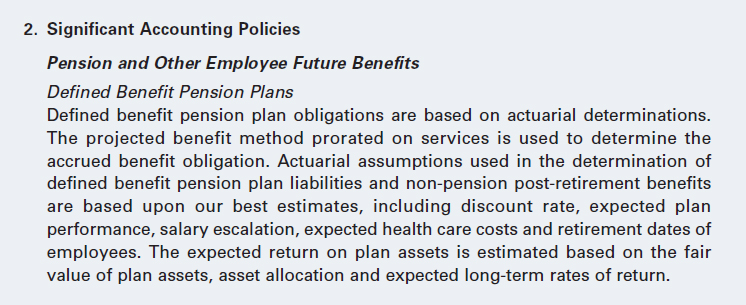

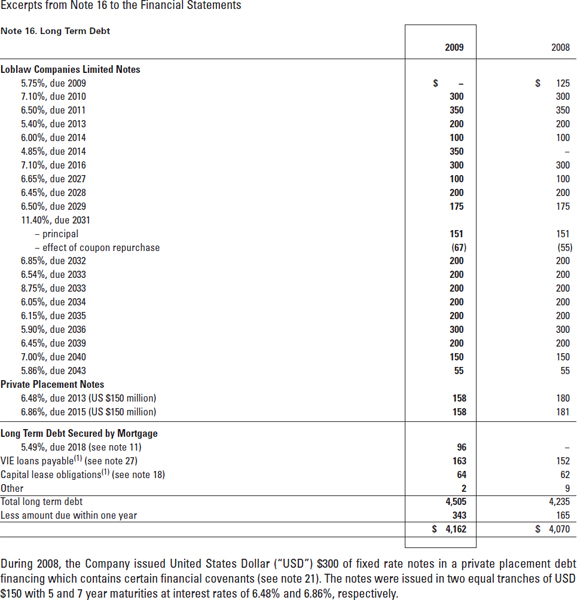

Pension Plan Disclosures

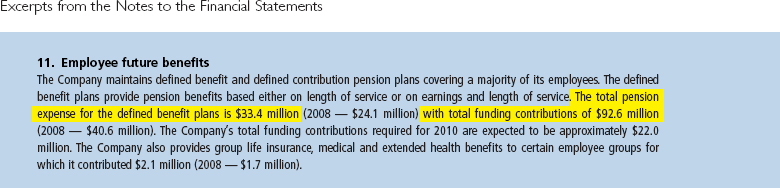

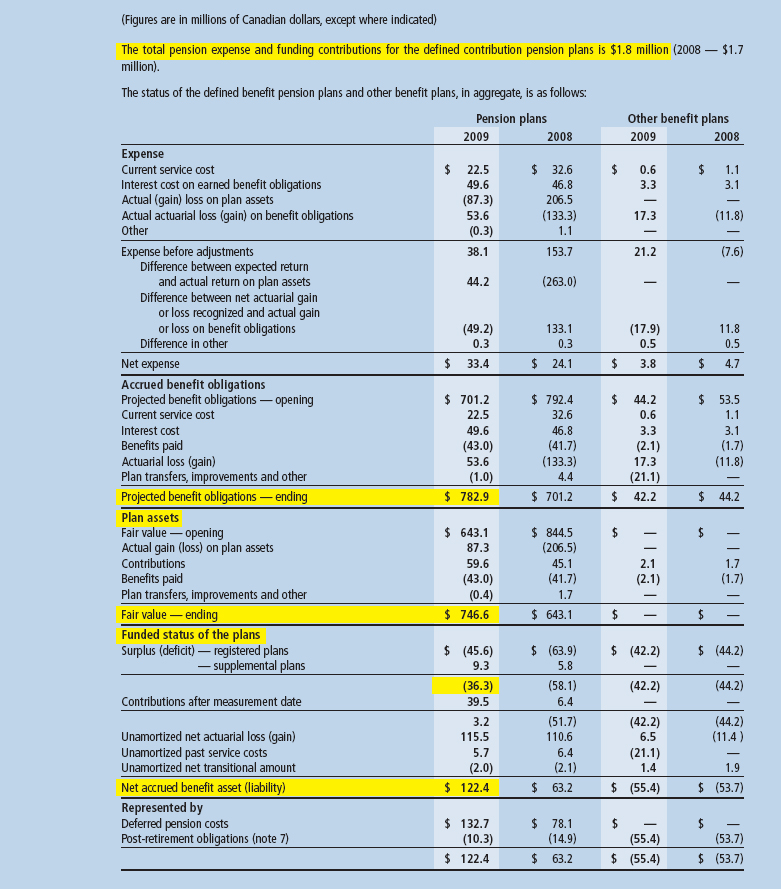

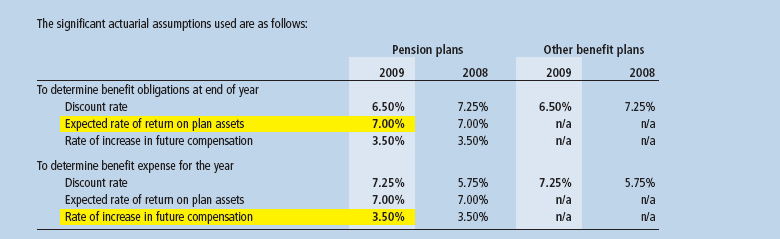

In Canada, for a defined contribution pension plan, the contribution amounts for the period must be disclosed. For a defined benefit plan, the required disclosures are very extensive. Rather than list all the requirements, we will look at the disclosures provided by West Fraser Timber Co. Ltd. in Exhibit 10-7. West Fraser Timber has both defined benefit and defined contribution pension plans, as well as some health care and life insurance benefits that it provides to its retired employees.

accounting in the news

Miners Go on Strike over Changes to Pension Plan

Defined benefit versus defined contribution pension plans were at the heart of the longest nickel strike in Canadian history, in Sudbury and Port Colborne, Ontario. The conflict between the mining company Vale and the United Steelworkers union lasted just under a year, and ended only after both sides made concessions. Among the employees' concessions was acceptance of a change to their pension plan. Under the new labour agreement, new employees will join a defined contribution plan, which is funded by a percentage of the employees' salaries, instead of a defined benefit pension plan, which is funded by the company rather than workers' contributions.

The company's pension plan deficit of about $730 million at the end of 2008 was one of the reasons the giant Brazilian mining company needed to make this change. Many defined benefit plans faced shortfalls when the recession hit, then took an additional beating as financial markets collapsed. These shortfalls can seriously affect a company's finances, since the company is required to put more cash into the plan to keep it solvent.

Sources: “Vale Pension Plan Short $729 million,” Thestar.com, February 1, 2010; Peter Koven, “Vale Workers Ratify New Contract,” Financial Post, July 9, 2010.

The note discloses that, for its defined benefit pension plans, West Fraser Timber's pension expense for 2009 was $33.4 million and its funding contributions were $92.6 million. For its defined contribution pension plans, both its pension expense and its funding contributions for 2009 were $1.8 million. Also, the latter part of the note discloses some of the key estimates that have been made regarding the pension plans. For example, West Fraser Timber assumed that its pension plan investments would earn an average annual rate of return of 7%, and that employees' compensation would increase at an average annual rate of 3.5%.

Perhaps the most important thing to note about pensions is that, for defined benefit plans, the amount of any pension plan asset or liability that appears on the company's statement of financial position does not represent the plan's funding status. Because of the complex procedures involved in accounting for pension plans (which are beyond the scope of an introductory text), a company might report a net pension plan asset on its statement of financial position, even though its pension plan is underfunded. Conversely, a company might report a net pension plan liability on its statement of financial position, even though its pension plan is overfunded. To determine whether a company's pension plan is underfunded, overfunded, or fully funded, users must read the notes to the financial statements.

EXHIBIT 10-7 WEST FRASER TIMBER CO. LTD. 2009 ANNUAL REPORT

WEST FRASER TIMBER CO. LTD. 2009 ANNUAL REPORT

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 8

Outline the accounting issues in the reporting of pension plan liabilities.

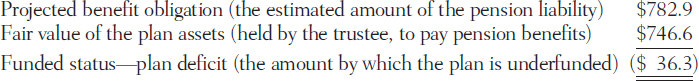

For example, Exhibit 10-7 shows the following for West Fraser Timber's defined benefit pension plans at the end of 2009 (in millions):

Despite the fact that its pension plans were underfunded by $36.3 million—which implies that the company has a liability for this amount—Exhibit 10-7 shows that a net pension plan asset of $122.4 million was recorded in West Fraser Timber's accounts. On its balance sheet (presented in Exhibit 10-8), this is split between the non-current asset deferred pension costs of $132.7 million, and a non-current liability post-retirement obligations of $10.3 million (which is included in “Other liabilities”). This illustrates the importance of reading the notes to financial statements.

IFRS INSIGHTS

The International Accounting Standards Board has proposed changes to pension accounting that, if adopted as IFRS, could have a significant impact on how pensions are accounted for. In particular, they could greatly reduce or eliminate the smoothing that has commonly occurred in the past because companies were allowed to recognize the effects of changes in the values of their pension plan assets and/or pension benefit obligations gradually, over extended periods of time.

EXHIBIT 10-8 WEST FRASER TIMBER CO. LTD. 2009 ANNUAL REPORT

EXHIBIT 10-8 WEST FRASER TIMBER CO. LTD. 2009 ANNUAL REPORT

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 9

Describe other post-employment benefits and explain how they are treated in Canada.

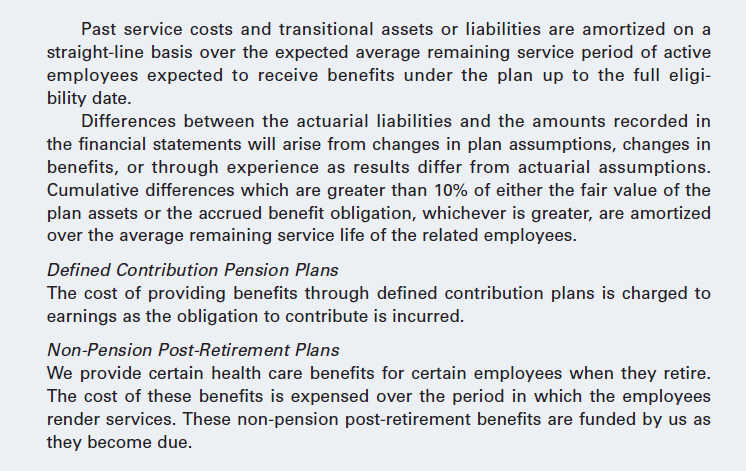

OTHER POST-EMPLOYMENT BENEFITS

As you just saw with West Fraser Timber, employers sometimes offer other types of post-employment benefits to their retirees, in addition to pensions. Health care benefits and life insurance are two of the most commonly offered benefits. Until recently, the obligation to provide these benefits was, for the most part, ignored in the financial statements of Canadian companies. Because of publicly funded health care in Canada, corporate obligations and exposure (risk) were limited. Therefore, the costs of providing these benefits were recorded on a pay-as-you-go basis; that is, the costs were expensed as the cash was paid out to the insurance companies that provide the benefits. However, companies are now required to account for these post-employment items in much the same way as they account for pensions.

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 10

Explain why deferred/future income taxes exist, and describe how they are reported.

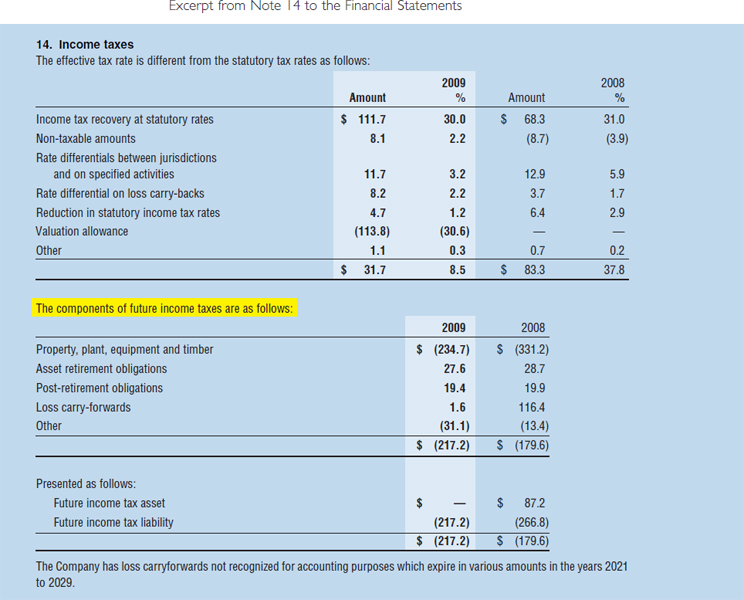

DEFERRED INCOME TAXES

Deferred income taxes (also known as future income taxes) arise because companies use two different systems for calculating their taxes. They use accounting standards for revenues and expenses to determine income tax expense on their statement of earnings, and they use Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) calculations of revenues and expenses to determine their income tax payable (that is, the amount of tax that must actually be paid to the government). In other words, companies prepare their financial statements according to the requirements of generally accepted accounting principles, but they prepare their income tax returns (which determine the amount of tax they have to pay each year) according to the requirements of the Income Tax Act and regulations. Differences between these two sets of calculations result in deferred income tax assets and liabilities.

For example, in Chapter 8 we discussed deferred income taxes because companies can use any one of several depreciation methods for accounting purposes but must use capital cost allowances (CCA) for tax purposes. The use of different methods for preparing financial statements and tax returns results in balances in companies' accounting records that are different from the balances in their tax records. These different balances result in deferred income tax effects.

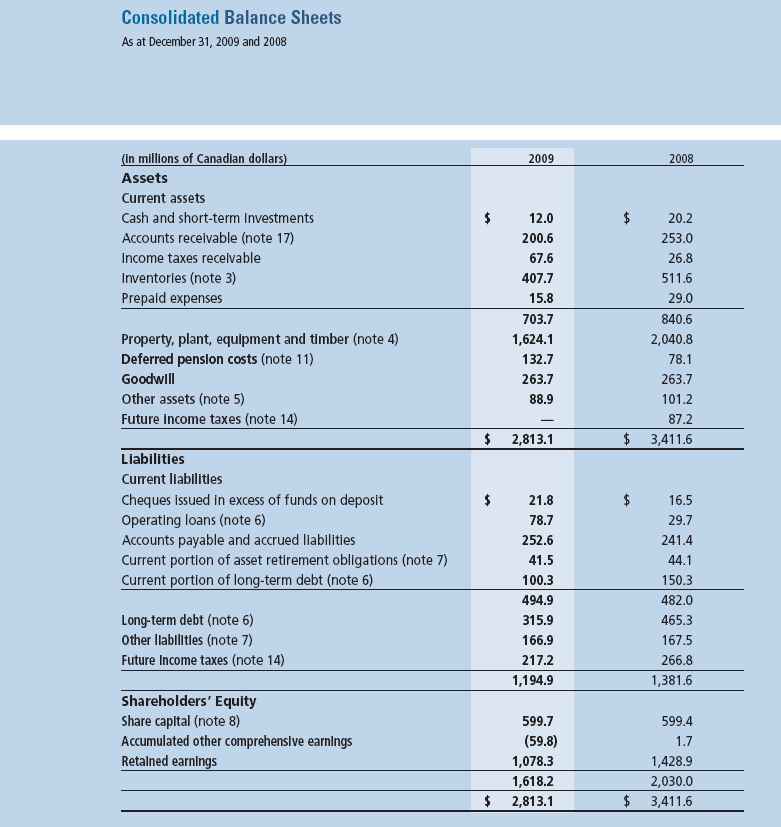

Another area that creates differences between what is reported in the accounting system and what is reported on a company's tax return is warranty costs, which we discussed in Chapter 9. For accounting purposes, the warranty expense deducted from income includes an estimate of future warranty costs, based on the revenue that was recognized in the current period. For tax purposes, however, only the actual amount that the company paid to repair items under warranty during the current period is allowed as a tax deduction.

There are also many other differences between accounting standards and tax regulations that give rise to deferred income taxes.

In Canada, the liability method is used to measure deferred income taxes. This method tries to measure the liability that will be incurred to pay more tax in the future, or the benefit that will be derived from paying less tax in the future, that is created by the differences between accounting calculations and tax calculations. Once the tax that is currently owed to the CRA and the deferred income tax have been calculated, the tax expense equals these two items combined (i.e., the income tax expense equals the income tax currently payable plus or minus the deferred income tax amount).

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 11

Record deferred/future income taxes in simple situations.

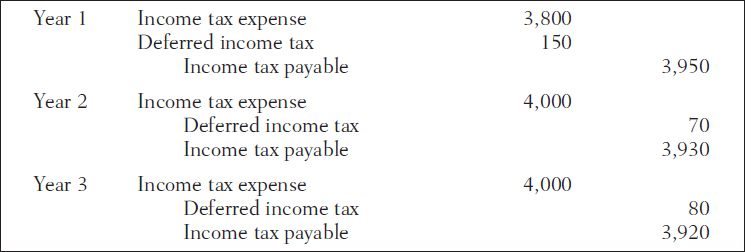

To illustrate the calculation of deferred income taxes, we will use the data in Exhibit 10-9 for a company that sells products with a three-year warranty. For simplicity, we will assume that the warranty is the only source of difference between the company's accounting records and its tax records.

For accounting purposes, the company estimates the probable costs associated with the warranty and records the total amount as warranty expense in the year of the sale, as well as a liability (warranty obligation). For tax purposes, however, the CRA does not permit a company to deduct the estimated warranty expense in calculating its taxable income; the company can only claim a tax deduction for the actual costs that it incurs each year to settle claims under the warranty.