chapter 12

FINANCIAL STATEMENT ANALYSIS

OVERVIEW OF FINANCIAL STATEMENT ANALYSIS

Reading the Financial Statements

Retrospective versus Prospective Analysis

Time-Series versus Cross-Sectional Analysis

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

- Explain why knowledge of the business is important when drawing conclusions about a company's future financial health.

- Describe the various ways of analyzing a company's financial statements.

- Identify the types of ratios that are best at providing insights for specific decisions.

- Calculate specific ratios that are used to assess a company's profitability, short-term liquidity, activity, and solvency, and explain how the ratios can be interpreted.

- Calculate and explain the uses of the earnings per share ratio and the price/earnings ratio.

- Understand the differences that might affect the ratio analysis of non-manufacturing or non-retail companies.

- Understand the need to exercise caution when interpreting ratios.

- Use ratios to assess a company's financial health through an analysis of its performance and financial position.

A Real-Life Exercise in Financial Management

Proper analysis of financial statements requires a good understanding of the statements' various components. No one knows this better than a group of finance students at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, B.C., who are putting their knowledge into action with the Student Investment Advisory Service (SIAS).

The SIAS was established in 2003 when a group of about 15 students in the university's Master's in Financial Risk Management program were given the opportunity to manage a fund, which then was worth approximately $6.5 million, representing about 5 percent of the total SFU endowment funds, says adjunct professor Derek Yee. In the following years, two other student groups joined the SIAS: master's students from the Financial Risk Management Program are calculating risk measures and offering advice on ways to reduce risks, and some undergraduates studying finance are acting as junior analysts.

The SIAS gives students the opportunity to apply what they have learned in the classroom. “As part of the normal portfolio management process, an Investment Policy Statement describes the parameters that the students must operate within,” explains Professor Yee. The students invest in three asset classes–cash, fixed income (Canadian), and equity (Canadian and global).

“We use a top-down approach,” says Enrico Chua, a student in the Master's in Financial Risk Management program, whose role was Canadian equity sector head for health care. “We first look at global macroeconomic factors like GDP, inflation, and interest rates. Then we look for industries that have wide economic moat and other competitive factors before drilling down to the individual companies.” The students then identify undervalued companies in good industries by looking into their financial statements. “We obtain at least five years of historical financial data from the company's balance sheet and statement of cash flow. Based on the accounting information and our understanding of the future business plans of the company, we forecast cash flows. We then use the discounted cash-flow method to come up with the fair value price of the stock.” The students also compare this target company with its peers to assess its competitive advantages. They write a report outlining the major financial information, valuation, and performance ratios, which they present to the SIAS group and Professor Yee for discussion, and then vote on whether to take action.

To review past performance, the students meet quarterly with their client, SFU's vice president of finance, who is responsible for the endowment funds' management. A business council composed of investment professionals from major financial institutions also critiques the students' performance. “Tough questions and constructive comments from the business council help shape and improve how we manage the fund,” says Mr. Chua. Following this quarterly review, the students meet with Professor Yee to discuss how they can improve SIAS.

And results have been good. The original $6.5 million had increased to about $9.2 million by the end of 2009. Some months, the SIAS outperforms the market, while other months are less successful. As Professor Yee points out, performance is only one measure; another is risk. “The students have a mandate to preserve wealth and they give that a higher priority than attempting to maximize return.”

The SIAS group at Simon Fraser University provides investment advice for some of the university's endowed funds. Not many students get the opportunity to work with real investments. The Master's in Financial Risk Management was a new program when the SIAS group was formed, but with the assistance of students from other SFU programs, the SIAS team is able to do a thorough analysis of potential investment options. One of the avenues of analysis that the SIAS group uses at the start of each investigation is financial statement analysis. The information that is gathered from the evaluation of the financial statements and their notes then forms the basis for their decision to go forward with further investigation. However, financial statement analysis is not the only basis on which they make their recommendations. They go on to look at discounted cash flow, perform a risk analysis, and complete their thorough analysis of the industry in which the company operates. Although financial statement analysis does not answer all questions, it does provide signals about financial health, cash flow, and operating efficiency.

Having worked your way through the previous chapters of this book, you now know the main issues in accounting, you can read and understand most of the items on financial statements, you are aware of the various methods that can be used to measure and report transactions, and you understand some of the limitations that affect the numbers on the statements. As we move through the various methods and ratios of financial analysis in this chapter, we are going to refer to some of the ratios that you have already seen in this text. In the first 11 chapters of this book, we described the basic components of the financial reporting system and how accounting numbers are accumulated and recorded. In most of these chapters, we also identified ratios that use the material that was being discussed. In this chapter, we pull all of these ratios together and summarize how financial information can be analyzed.

USER RELEVANCE

As a user, you need to analyze financial information effectively so that you can make knowledgeable decisions. This involves more than a basic understanding of what each individual statement means. You need to understand the relationships among the three major financial statements and the methods that produce the numbers. You also need to compare and contrast these relationships over time and among different companies. Our current discussion was left until this chapter because proper analysis requires a good understanding of all financial statement components.

As we worked through the material in the book, we introduced the ratios that pertained to the topics under discussion. While this has given you some tools, they are not organized cohesively, and you now need to think about analysis as a structured activity. You need to know what information will help you make informed decisions and then identify the tools that will give you that information. With this in mind, the ratios in this chapter have been organized according to decision-making needs.

This chapter provides an overview of financial statement analysis and a discussion of the basic ratios used. However, because financial statement analysis is very complex, it can serve only as an introduction. Remember two things as you work through this chapter. First, there is no definitive set of rules or procedures that dictate how to analyze financial statements. Second, every analysis should be tailored to suit the underlying reason for making the analysis. These two features make comprehensive analysis quite complex. A more detailed discussion of financial statement analysis is left to more advanced texts.

OVERVIEW OF FINANCIAL STATEMENT ANALYSIS

Financial statements are typically analyzed for a specific purpose. An investment analyst or a stockbroker, for example, may undertake an analysis in order to recommend that a client buy or sell shares. A bank's commercial loans officer may perform an analysis of a client's financial statements to decide whether the client will be capable of paying back a loan the bank is considering. A student looking for a job may analyze a company to decide whether it is a suitable company to work for.

Each analyst will tailor the analysis to the demands of the decision to be made. For example, a banker trying to decide whether to make a short-term loan may restrict the analysis to the company's short-term cash-producing capabilities. The investment analyst, on the other hand, may focus on its long-term financial health.

In this chapter, we take a very general approach to financial statement analysis. While no particular decision is considered as the various ratios are discussed, we do discuss decision contexts where one particular ratio may be more helpful than others. Before turning to specific ratios, however, and whatever the decision to be made, one of the first things you have to do is understand the business.

Understanding the Business

Understanding the business means more than understanding a company's financial statements. It means having a grasp of the operating activities of the business, the underlying economics, the risks involved, and the external economic factors that are crucial to the company's long- and short-term health. It means that you must understand the various types of businesses that the company is engaged in. For example, a large company such as Rogers Communications Inc. is involved in more than just providing cell phone and cable access to consumers. In its wireless division, it provides wireless voice and data communications services. The cable division provides cable television services and high speed Internet. The media group not only operates radio and television stations, including Citytv in Toronto and The Shopping Channel, but also publishes consumer magazines and professional publications, and owns the Toronto Blue Jays Baseball Club. An analyst who thinks that Rogers is only in the telephone and cable business has a very inaccurate view of the risks involved in lending Rogers money or in buying its shares.

Companies follow different strategies to achieve success. Although a detailed discussion of corporate strategy is beyond the scope of this book, you should be familiar with a few basic strategies that companies follow. The two most common strategies are being a low-cost producer and following a product differentiation. A low-cost producer focuses on providing goods or services at the lowest possible cost and selling at low prices. To be successful, these companies need to sell a high volume of goods at the lower prices. This strategy works best when competing products are similar and price is the most important decision factor for customers. Discount grocery chains or discount retailers usually follow this strategy. The other strategy is to sell products that are specialized or to provide superior service that customers are willing to pay a premium for. If the company can make a higher profit margin on the goods or services provided, it does not need to sell as many goods to make the same level of total profit as a company that sells more for less—they can succeed with a lower volume. Gourmet grocery or specialty stores and high-end retailers usually follow this strategy. Understanding the company's strategy will help you interpret the financial results and explain differences if, for example, you are trying to compare a discounter to a specialty store and are wondering why the results are so different.

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 1

Explain why knowledge of the business is important when drawing conclusions about a company's future financial health.

A basic understanding of the company's range of business activities, including their recent achievements and management's future expectations for them, can usually be had by reading the first sections of the company's annual report. The first half of the annual report in North America is divided into two parts. The first part contains the description of the company, some general highlights of the year, and letters to the shareholders from the CEO and the chief financial officer. Following that is the Management Discussion and Analysis (MD&A). This is a very important section for an analyst to read, because in it management must discuss many aspects of the company's financial performance in greater detail. It should include a discussion not only of past results, but also of management's expectations for the future and the risks the company is facing. The intention of the MD&A is to allow the user to see the company through the eyes of management. Although this descriptive section of most annual reports does not explain everything you need to know about the company, it does provide some insight into what the company does and the types of risks it faces. You should also listen to the financial news and read financial newspapers and magazines to find additional information about the company and the industry in which it operates. Once you have an overall view of the types of businesses operated by the company, you should next read the financial statements, including the auditor's report and the notes to the financial statements. The financial statements are usually found in the second half of an annual report.

For purposes of illustration in this chapter, we are going to use the financial statements of SOCIÉTÉ BIC (BIC). Headquartered in a suburb of Paris, France, BIC is familiar to most students as a world leader in the stationery (pens and other office supplies), lighter, and shaver markets. In 2010, as a result of acquisitions in 2009, BIC added advertising and promotional products (custom printed calendars, bags, pens, and so on) as a fourth product area. BIC's strategy, as indentified in its annual report, is to focus on generating sales growth with new products and extension of its product line, both focused on innovation. The company's goal is to produce consistent quality products at a lower cost, either in-house or, to a lesser extent, by outsourcing, to increase flexibility or to take advantage of new technologies. BIC sells its products to office product stores and other retailers, and to distributors and wholesalers. The company prepares its financial statements in French in accordance with regulations governing the stock market in Paris, and refers to the English translation used in this chapter (and available on the companion website) as a reference document. In the remainder of the chapter, we will refer to the document as an annual report, as it is similar in format and content to the other annual reports we have used throughout the book.

Reading the Financial Statements

The first thing to read in the financial statements is the auditor's report, as it states whether appropriate accounting policies were followed and whether the statements present the company's operating results and financial position fairly. This report is important because the auditor is an independent third party who is stating a professional opinion on the fairness of the numbers and disclosures reported in the financial statements. The role of the auditor and the audit report were introduced in Chapter 1.

Remember that the auditor's report does not guarantee the accuracy of the information contained in the financial statements. Financial statements are prepared by management, and management has primary responsibility for them. Auditors express their opinion on whether the financial statements present the information fairly according to generally accepted accounting principles. The auditor's report does not indicate whether the information contained in the financial statements is good or bad. It is the reader's responsibility to interpret the information provided.

An example of a typical unqualified auditor's opinion, provided by Grant Thornton and Deloitte & Associates Chartered Accountants for the 2009 financial statements of BIC, is shown in Exhibit 12-1. As you may recall from Chapter 1, an unqualified (or “clean”) audit opinion is one in which the auditors do not express any concerns, reservations, or qualifications regarding the financial statements. Without any exceptions, they state that, in their professional opinion, the financial statements give a true and fair view of the company's financial position and the results of its operations in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles. This is what the users of the financial statements want to see; any other type of audit opinion warrants very careful consideration.

One of the differences in the presentation of the financial statements under French GAAP is that the auditor's report is found after the financial statements and notes, as opposed to the traditional North American presentation, where it is presented before the financial statements. Similar to Canadian audit reports, BIC's audit report contains three components: the auditors express their opinion on the financial statements, state their justifications, and outline the specific procedures they used.

After reading the auditor's report, the second step is to read each of the major financial statements to ensure that the results make sense for the types of activities that the company is engaged in. Use your knowledge from this course to look for unusual account titles and unusually large dollar items. For example, if there is a large loss item on the statement of earnings, the nature of the loss is important. Is it an item that could be expected to continue into the future, or is it a non-continuing item?

Unusual account titles may indicate that the company is involved in a line of business that is new, which could have serious implications for future operations. For example, if a manufacturer suddenly shows lease receivables on its statement of financial position, this probably indicates that it has started to lease assets, as well as sell them. The leasing business is very different from the manufacturing business and exposes the company to different types of risk. You must take this new information into consideration when evaluating the company.

A reading of the financial statements is not complete unless the notes to the financial statements are read carefully. Because the major financial statements provide summary information only, there is not much room on them to provide all the details that are necessary for a full understanding of the company's transactions. The notes provide a place for more detail and discussion about many items on the financial statements. Also pay attention in the notes to the summary of the company's significant accounting policies. Remember that IFRS allows considerable flexibility in choosing accounting methods, and different choices result in different amounts on the financial statements, so you should be aware of the choices that management made. These will generally be listed in the first note to the financial statements.

Once you have an overall understanding of the business and the financial statements, you can begin a detailed analysis of the financial results.

EXHIBIT 12-1 SOCIÉTÉ BIC 2009 ANNUAL REPORT

EXHIBIT 12-1 SOCIÉTÉ BIC 2009 ANNUAL REPORT

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 2

Describe the various ways of analyzing a company's financial statements.

Retrospective versus Prospective Analysis

As discussed earlier, most analysis is done with a particular objective in mind, and as most objectives involve making decisions that have future consequences, it follows, therefore, that almost every analysis of a set of financial statements is, in one way or another, concerned with the future. Because of this, you should make a prospective (forward-looking) analysis of the company to try to determine what the future will bring. For example, commercial loans officers in banks try to forecast companies' future cash flows to ensure that loans will be repaid.

The problem with prospective analysis is that the world is an uncertain place; no one can predict the future with complete accuracy. Analysts, however, are expected to make recommendations based on their predictions of what the future outcomes will be for specified companies. In trying to predict the future, some of the most reliable sources of data you have are the results of a company's past operations, as summarized in the financial statements. To the extent that the future follows past trends, you can do a retrospective analysis to assist in predicting the future. You must also understand the economics of a company well enough to know when something fundamental has changed in the economic environment to make it unlikely that the company's past results will predict the future. In such a situation, you cannot rely on the retrospective data.

If you believe that retrospective data may be useful in predicting the future, a complete analysis of those data is in order. Two major types of analysis of retrospective data are time-series and cross-sectional analyses.

Time-Series versus Cross-Sectional Analysis

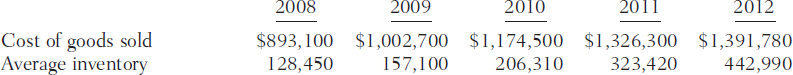

In a time-series analysis, the analyst examines information from different time periods for the same company, to look for any patterns in the data over time. For example, you may look at the sales data over a five-year period to determine whether sales are increasing, decreasing, or remaining stable. This would have important implications for the company's future sales. The assumption underlying a time-series analysis is that there is some predictability in the time series; that is, past data can be used to predict the future. Without this assumption, there is no reason to do a time-series analysis.

Many companies recognize the importance of time-series information and provide five- or 10-year summaries to assist in making this analysis. In the first part of its annual report, BIC prepares a review covering a three-year period. Because this is not adequate for the purpose of a trend analysis, Exhibit 12-2 extracts some of the key accounts from BIC's analysis and has extended the summary to five years using data from earlier annual reports. In BIC's information, it is interesting to note that both net sales and group net income increased from 2005 to 2007, and then fell in 2008. Sales growth rebounded to a new, higher level of sales in 2009, and although net income increased over 2008, it was still below the amounts earned from 2005 to 2007. The income from operations (income after all operating expenses but before tax and interest expense) exhibited the same pattern as the net income.

A review of the balance sheet items presented shows that assets grew substantially between 2008 and 2009, as a result of the acquisitions BIC made to establish itself in the promotional products market and an acquisition of a stationery company in India, undertaken to increase the company's presence in that geographic market. It appears that the acquisitions were financed by increases in both non-current borrowings and equity. A review of the cash flow statement information indicates that BIC spent a large sum on investing activities in 2009, but the cash generated from operations increased and it had a very large cash and cash equivalents balance (€478.9 million) at the end of the year. Some companies include non-financial data, such as the number of employees or number of retail outlets, in their financial summaries. BIC included the number of shares outstanding.

HELPFUL HINT

A word of caution: Some companies, like BIC, present their financial information with the earliest year closest to the account titles. Most companies present their information the other way, with the most recent year closest to the account titles. When you are reading financial statements, be careful to observe the format used or you may end up thinking sales are falling when they are growing!

After this brief review, an analyst would now have identified that although the company's stated strategy may be growth and producing quality products at low costs, the company has not achieved that consistently over the period. The analyst will be interested in further analyzing the performance of the company to try to determine the reasons for the lower level of net income and to assess whether BIC will be able to repay the additional debt it has taken on.

A cross-sectional analysis compares the data from one company with the data from another company for the same time period. Usually, the comparison is with another company in the same industry (a competitor perhaps), or with an average of the other companies in the industry. For example, you might look at the growth in sales for General Motors of Canada compared with the growth in sales for Ford of Canada. Other cross-sectional analyses might compare companies across different industries (General Motors of Canada compared with Rogers), different countries (General Motors of Canada compared with Nissan of Japan), and so forth. However, any cross-sectional comparisons must consider that different industries may have different accounting principles (for example, accounting principles for banks and insurance companies are slightly different from those for most other industries). Comparing across countries is more difficult if different accounting standards are used in different countries. However, investment analysts want to recommend the best investment strategy to their clients using as wide a range of investments as possible. To make the best recommendation, they must consider the return versus risk trade-off across many companies. They must, therefore, directly compare companies in different industries and different countries. One of the advantages of the growing use of IFRS in Canada and around the world is that there will be fewer accounting differences and, therefore, easier comparisons.

The choice of which type of analysis to conduct is driven, in part, by the type of decision that motivated the analysis. In a lending situation, for example, the commercial loans officer will use a time-series analysis of the company in conjunction with a cross-company comparison. The time-series analysis is important because it will help the lender determine the company's ability to repay any money loaned. As part of the decision-making process, the lender must also be aware of industry trends in order to get an overall assessment of how well a particular company performs relative to its competitors. This information will help ascertain the company's future viability.

Data to Be Used

The type of data that is used in a time-series or cross-sectional analysis will vary depending on the purpose of the analysis. Three general types of frequently used data are raw financial data, common size data, and ratio data.

Raw Financial Data

Raw financial data are the data that appear directly in the financial statements. An example of a time-series analysis of this type of data would be time-series data available in the annual report from the income statements, cash flow statements, and balance sheets, similar to that shown for BIC in Exhibit 12-2. Cross-sectional analysis can also be used with this type of data. For example, you might compare total revenues across companies in the same industry for the past three years. Annual reports may also contain data other than strictly financial data, such as numbers of employees or sales volumes expressed in physical units rather than dollars.

In the remainder of the chapter, data from BIC's financial statements will be used to illustrate various types of analyses. These raw financial statement data appear in Exhibit 12-3, which includes the balance sheets, income statements, and cash flow statements.

Common Size Data

Although a company's raw data can reveal much about its performance, certain relationships are more easily understood when some elements of the raw data are compared with other elements. For example, in the income statement for BIC in Exhibit 12-3B, you can see that sales increased from €1,456,088 thousand in 2007 to €1,562,696 thousand in 2009. Cost of goods has also increased over this period from €741,063 thousand to €842,952 thousand. What happened to gross profit margins, on a relative basis? This is a question of the relationship between the costs and the revenues. One way to address this question is to compare the cost of goods sold expressed as a proportion of the sales revenue. Often, this is done by preparing a set of financial statements called common size statements.

EXHIBIT 12-3A SOCIÉTÉ BIC 2009 ANNUAL REPORT

EXHIBIT 12-3A SOCIÉTÉ BIC 2009 ANNUAL REPORT

EXHIBIT 12-3B SOCIÉTÉ BIC 2009 ANNUAL REPORT

EXHIBIT 12-3B SOCIÉTÉ BIC 2009 ANNUAL REPORT

EXHIBIT 12-3C SOCIÉTÉ BIC 2009 ANNUAL REPORT

SOCIÉTÉ BIC 2009 ANNUAL REPORT

In a common size statement of earnings, all line items are expressed as percentages of sales. Exhibit 12-4 presents a common size income statement for BIC, with every item calculated as a percentage of net sales.

We observed from the key figures in Exhibit 12-2 that sales have been increasing for BIC, except in 2008, but net income had fallen in 2007 and did not fully recover when sales did in 2009. This common size statement of earnings gives us a better understanding of those changes. It shows that BIC's cost of goods as a proportion of sales has been increasing over the three-year period, and that proportionate net income has been decreasing. Cost of goods has gone from 50.9% of sales to 53.9%, a full 3% increase. It is costing BIC more to produce the goods it sells. This has caused the gross profit to fall from 49.1% to 46.1% and signals to the user that BIC has been ineffective in controlling its major costs. It is not clear if the increase reflects a shift to selling more products that are more expensive to produce, if increases in sales prices have not kept pace with increases in cost, if price cuts were required due to competitive or economic conditions, or if cost control has just been ineffective. An analyst would want to try to find out more information, either from management or from performing additional analysis, about the cause of the change. An analyst will examine a company's financial statements carefully when sales are rising or falling. If sales are rising and the cost of those sales rises proportionately more than the sales themselves, the new sales are costing the company more and management should be looking for ways to control the costs.

Common Size Statements of Income

As a percentage of sales, when all other costs remain the same, an increase in the cost of sales results in an identical decrease in net income. Imagine if you sell an item for $1.00 and it now costs you $0.03 more to make or acquire the item than it did last year. This means there will be $0.03 less to spend on other items or left over as net income. For BIC, net income as a percentage of sales actually decreased by 2.2% over the period, from 11.9% of sales to 9.7%. As BIC experienced a 3% increase in its cost of goods sold, it must have been able to control other operating costs well enough to prevent net income from declining by the full 3% of the rise in its cost of goods sold. Many other items on the income statement are proportionately similar to 2007, although the operating expenses seem to be declining relative to sales. This could indicate that management is doing a better job at controlling those operating expenses. As well, income tax as a proportion of sales decreased, but income tax expense is generally not under management's control. The signals on this common size statement are mixed—cost of goods is increasing but other expenses decreased slightly. Overall, however, the net effect is a decrease in net income.

Common size statements could also be prepared for the balance sheet and the cash flow statement. The common size data could then be used in a time-series analysis, as they were earlier, or they could be used in a cross-sectional analysis of different companies. In fact, common size statements are particularly useful in cross-sectional analysis because they allow you to compare companies of different sizes.

Ratio Data

Common size data are useful for making comparisons of data items within a given financial statement, but they are not useful for making comparisons across the various financial statements. Ratios, on the other hand, compare a data element from one statement with an element from another statement, or with an element in the same statement. These ratios can then be used in a time-series or cross-sectional analysis. Ratio data are potentially the most useful analytical tool because they reveal information about relationships between the financial statements.

Although ratios tell you about the relationship between two figures and changes in that relationship from year to year, or compared to another company, they do not tell you the reason for the changes. You will usually need to do further research and analysis, or talk to management, to understand the reasons for the changes. Sometimes changes in ratios are referred to as red flags—they identify areas that the user needs to investigate further.

To illustrate the relationships that can be analyzed using ratio analysis, the remainder of the chapter is devoted to discussing various ratios and their calculation and interpretation. Most of them have already been introduced in previous chapters, but a discussion of the ratios as they relate to one another should help you to better understand and appreciate the usefulness of ratio analysis.

Before you begin ratio analysis, it is important to remember that financial statements are based on IFRS. This means that they involve certain accounting policy choices, assumptions, and estimates. As well, many of the assets and liabilities are reported at historical cost values rather than market values. Consequently, the limitations inherent in the financial statements are carried over into the ratios that are used to evaluate them.

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 3

Identify the types of ratios that are best at providing insights for specific decisions.

RATIOS

Ratios explain relationships among data in the financial statements. The relationships differ across companies, if for no other reason than that the companies' underlying transactions are different. For example, a manufacturing company is very concerned about the management of inventory and focuses on various ratios related to inventory. A bank, on the other hand, has no inventory and would not be able to calculate such ratios. It might, however, be very concerned about the loans that it makes, whereas a manufacturer would probably not have any items comparable to loans receivable.

Because of the differences across companies, it is impossible for us to address all the ratio issues related to all types of industries. The main focus of our discussion will, therefore, be restricted to BIC, but most of our discussion also applies to companies in other manufacturing and retailing industries. At the end of the chapter, we include a brief discussion of ratio analysis for non-retailing/manufacturing companies in areas where there may be differences in interpretation.

The ratios that will be discussed are divided into four general categories, but you will see that they are all related. The categories are performance, short-term liquidity, activity, and long-term solvency. Most of these ratios apply to any company regardless of the nature of its business, but some (such as inventory ratios) apply only to certain types of businesses. A fifth group of ratios applicable to equity analysis will also be discussed.

Before the calculations of the various ratios are presented, one general caveat is given. There are often several ways to calculate a given ratio. Therefore, it makes sense to understand the basis of a calculation before you attempt to interpret it. The use of ratios in this book will be consistent with the definitions given. However, if you use similar ratios from other sources, you should check the definition used in that source to make sure that it is consistent with your understanding of the ratio.

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 4

Calculate specific ratios that are used to assess a company's profitability, short-term liquidity, activity, and solvency, and explain how the ratios can be interpreted.

Profitability Ratios

Net earnings and cash flow as measures of performance have already been discussed in Chapters 2 and 4. Although much can be learned from studying the statement of earnings and statement of cash flows, in both their raw data and common size forms, the ratios discussed in this section complement that understanding and also draw out some of the relationships between these statements and the balance sheet.

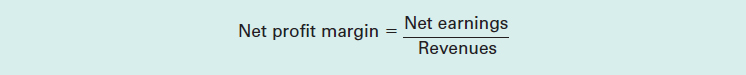

Net Profit

In Chapter 2 we used the profit margin ratio, or more correctly the net profit margin, to measure a company's profitability relative to its revenues. This ratio provides information about the company's ability to control all costs and is calculated by dividing the company's net earnings by the revenues that produce those earnings:

The net profit margin is a good starting point to determine if a company is profitable, but it does not provide any information about how that profit was achieved or what resources were required to earn it. Were the earnings mostly from the company's primary operations, or did the company have significant earnings from investment income or one-time gains from selling other assets? When trying to predict a company's future earnings, the current sources and types of earnings are an important consideration. A company cannot sell off assets continuously and expect to stay in operation for long.

Earlier in the chapter, we identified different strategies a company could be using. Is the company's strategy to produce at the lowest cost and sell a high volume? Or does it sell a differentiated or premium product at a higher margin and lower volume? Answers to these questions can be obtained by looking at other margin ratios calculated from the statement of earnings.

Gross Profit

The gross profit margin measures the proportion of sales revenue available to pay all other operating costs after the costs of goods sold. It is calculated as gross profit divided by revenues. It is a key ratio in assessing a company's profitability. The cost of goods sold is, for most businesses, the largest single cost incurred and companies need to pay close attention to this margin to ensure that there is enough money available after those costs to pay all other expenses. Changes in this ratio would indicate a change in the product's profitability and may indicate changes in the cost structure or pricing policy.

Some companies choose not to disclose the cost of goods sold separately on the statement of earnings because they do not want competitors to know that information. In those situations, the cost of goods sold is usually grouped with other operating costs and an operating profit margin is shown. Calculating a ratio for that margin would also be useful, but would not provide the same level of information as a gross margin and a separate analysis of operating costs.

BIC does disclose the cost of goods sold separately on its income statement, and both the net profit margin and gross profit margin were calculated as part of the common size income statement in Exhibit 12-4 and are repeated here. In 2009, for every €1 BIC made in sales, it had €0.461 left over after covering the cost of the item that contributed to the €1 in sales. And after paying all other costs, it had €0.097 left in profit on the €1 of sales.

It should be apparent to you that gross profit margin and cost of goods sold are reciprocal figures. If BIC had €0.461 of gross profit left over from the euro in sales after paying for the related cost of goods sold, it must have cost BIC €0.639 (€1 – €0.461) to earn that euro in sales. Some analyses focus on the cost to make the good—a cost of goods sold percentage—whereas the gross profit margin ratio views it from the gross profit margin perspective. The conclusions drawn from either approach would be the same.

In the discussion of both the financial highlights and the common size income statement, we raised concerns that BIC's profitability was declining. We now see that net profit margin decreased by 0.5% from 2008 to 2009, but gross profit margin decreased by more, 1.0%. BIC has less money available after producing its goods to pay other costs. It appears that costs have been rising faster than selling prices. This could be due to several factors. It may be due to poor cost controls. It may be that the company has chosen (or been forced) to lower prices relative to costs. Or perhaps there has been a change in BIC's product mix and it is selling more low margin items than previously. Further analysis or discussions with management would be necessary to know the exact cause, but the concern has been identified. The fact that the net profit margin did not decrease by the same amount as the gross profit margin indicates that BIC is doing a better job of controlling (is spending less per euro of sales) its other costs. This is a positive sign.

PROFIT MARGINS—SOCIÉTÉ BIC

Net profit margin

Gross profit margin

![]()

In addition to the profitability of earnings relative to revenues, it is important to examine the earnings relative to the amount invested to earn those earnings. If two companies generate the same amount of net earnings, but one company requires twice as many assets to do so, that company would clearly be a less desirable investment.

In Chapter 4, a performance ratio called the return on investment (ROI) was briefly discussed in generic terms as a measure of an investment's performance.

The generic form of the ROI calculation can be used to formulate several different ratios, depending on the perspective taken in measuring performance. For example, one perspective is that of the shareholders, who make an investment in the company and want to measure the performance of their investment. Return on equity (ROE), which we also saw in Chapters 4 and 11, is a form of the ROI measure that captures the return to shareholders.

A second perspective is that of management. Management obtains resources from both shareholders and debt holders. Those resources are then invested in assets. The return generated by the investment in assets is then used to repay the debt holders and the shareholders. The profitability of the investment in assets is, therefore, very important. First seen in Chapter 8, return on assets (ROA) captures this type of ROI.

In this chapter, both ROA and ROE are considered.

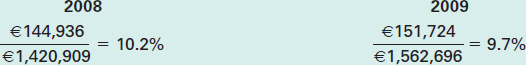

Return on Assets (ROA)

Company management must make two fundamental business decisions. The first is the type of assets in which the company should invest (sometimes referred to as the investment decision), and the second is whether to seek more financing to increase the amount that the company can invest in assets (referred to as the financing decision). The ROA ratio, in this book, separates the investment decision from the financing decision. Regardless of the mix of debt and shareholder financing, this ratio asks the following question: What type of return is earned on the investment in assets? From this perspective, the return on the investment in assets should be calculated prior to any payments or returns to the debt holders or shareholders. Net earnings is a measure that is calculated before any returns to shareholders, but after the deduction of interest to the debt holders. Therefore, the net earnings, if it is to be used as a measure of return on assets, must be adjusted for the effects of interest expense so that the financing effects are removed from the earnings amount, resulting in a measure of the earnings generated by the assets that is available to pay both debt holders and shareholders.

A complicating factor in calculating this ratio is that interest is deductible in the calculation of income tax expense. Therefore, if interest expense is to be removed from the net earnings figure, we must also adjust the amount of income tax expense that would result. In other words, the tax savings (i.e., the reduction in income tax expense) associated with this interest deduction must also be removed. The ROA ratio is then calculated as the ratio of the return (income before interest) divided by the investment in total assets, as follows:

Many companies show interest expense as a separate item on the statement of earnings. The interest expense for BIC is included in the finance costs on the income statement, and can be determined from reading Note 6, which is shown in Exhibit 12-5. Also included in the finance costs are gains or losses on some types of foreign currency exchanges and derivatives used for hedging, both of which are beyond the scope of this book.

EXHIBIT 12-5 SOCIÉTÉ BIC 2009 ANNUAL REPORT

EXHIBIT 12-5 SOCIÉTÉ BIC 2009 ANNUAL REPORT

Excerpt from Note 6: Finance Costs/Revenue

The effective income tax rate can be calculated by dividing the income tax expense on the income statement by the income before tax (in 2009, €70,843 ÷ €218,747 = 32.4%). Based on the data for BIC, the calculation of the ROA for 2009 and 2008 has the following results:

RETURN ON ASSETS (ROA)—SOCIÉTÉ BIC

The 8.6% ROA in 2009 indicates that BIC earned 8.6% on the average total assets before making any payments to the suppliers of capital. This 8.6% should be compared with the 9.2% ROA earned in 2008. The decrease in the ROA is consistent with the decrease in profitability that we observed with the net profit margin and the increase in total assets in the common size financial statements. It should be compared with the ROA of other companies of similar risk.

The ROA is useful in measuring the overall profitability of the funds invested in the company assets. However, comparisons of ROAs across industries must be made with care. The level of ROA reflects, to some extent, the risk that is inherent in the type of assets that the company invests in. Investors trade off the risk for the return. The more risk investors take, the higher the return they demand. If the company invested its assets in a bank account (a very low-risk investment), it would expect a lower return than if it invested in oil exploration equipment (a high-risk business). Although this factor cannot explain all the variations in ROA between companies, it must be kept in mind. It may be more appropriate either to do a time-series analysis of this ratio, or to compare it cross-sectionally with a direct competitor in the same business. Data obtained from a source of industry ratios, such as Dun and Bradstreet, can provide you with median measures of ROA that can be used for comparison purposes to determine whether the calculated ROA of a specific company is reasonable or not.

There exists a useful breakdown of the ROA ratio that can provide insight into what caused a change in the ROA. The most common breakdown of this ratio is as follows:

This breakdown of the ROA ratio into a profit margin ratio and a total asset turnover allows the analyst to assess some of the reasons for a company's ROA having gone up or down. Note that this is not the same profit margin ratio as the net profit margin ratio calculated earlier, because it is calculated using the profit or earnings before the after-tax interest expense. Changes in this ratio would indicate a change in the product's profitability and may indicate changes in the company's cost structure or pricing policy. The total asset turnover is the ratio of sales to total assets, or the dollars of sales generated per dollar of investment in assets. Changes in this ratio could reflect an increase or decrease in sales volume or major changes in the level of investment in company assets.

The breakdown for BIC in 2009 would be as follows:

ROA BREAKDOWN—SOCIÉTÉ BIC

These calculations indicate that in 2009 BIC earned the 8.6% ROA by achieving a profit margin of 10.1% and a total asset turnover of 0.85 times. Note that the decrease in the ROA from 2008 was a result of both a decrease in the profit margin (from 10.5% to 10.1%) and a small decrease in the total asset turnover ratio (0.87 to 0.85). So declining profitability is not the only difficulty BIC faced; there was also a decrease in sales generated per euro of assets. That could reflect declining efficiency of assets, or investment in new assets that have yet to reach their full potential to generate sales. The decrease in total asset turnover is small, and would need to be compared to other years or other companies before a conclusion could be reached about whether it should be of concern to an analyst. We saw earlier that BIC's assets grew as a result of an acquisition in 2009, and it appears that those assets have been able to generate close to BIC's traditional level of sales. The decrease in profitability, however, is consistent with earlier concerns we identified about BIC's performance in recent years.

Earlier in the chapter, we identified two strategies a company could be pursuing. The same ROA could be achieved by companies in the same industry with different strategies. For example, a discount retailer operates on smaller profit margins and hopes to make that up by generating a larger volume of sales relative to its investment in assets (giving it a higher asset turnover). Discounters generally have less invested in their retail stores. Other full-price retailers have a much larger investment in assets relative to their sales volume (giving them a lower asset turnover), and they must therefore charge higher prices (giving them a higher profit margin) to achieve a comparable ROA. Both businesses face the same general sets of risks and should earn comparable ROAs.

Return on Equity (ROE)

Return on equity (ROE), mentioned earlier in this section, is the return that shareholders earn on their investment in the company. There is an additional issue that must be understood in calculating this ratio. If there is more than one class of shares (generally the second class would be preferred shares), the ROE calculation should be done from the point of view of the common shareholders. This means that any payments to the other classes of shares (preferred dividends, for example) should be deducted from net earnings in the numerator of this ratio, because these amounts are not available to the common shareholders. Similarly, the denominator in such cases should include only the shareholders' equity accounts that belong to common shareholders. This usually means that the preferred shares equity account is subtracted from the total shareholders' equity to arrive at the common shareholders' equity.

HELPFUL HINT

When removing the preferred dividends for this calculation, you need to remove the dividends that were owed in the current year for preferred shares that are cumulative. If the current year's owed dividends are removed each year, it is not necessary to remove the dividends in arrears that were paid in a given year since prior years already included them in an ROE calculation.

The calculation of a company's ROE is as follows:

As BIC only has common shares, we do not have to consider preferred shares and their related dividends. However, the minority interest that is shown in BIC's shareholders' equity section is not an investment by common shareholders; it reflects the fact that BIC does not own 100 percent of some of the subsidiaries that it controls. Minority interests are discussed further in Appendix B, but for now it is enough for you to understand that they are not included in common shareholders' equity and hence the denominator for BIC is the Group Shareholders' equity amount from the balance sheet.

For BIC, the calculation of ROE is as follows:

RETURN ON EQUITY (ROA)—SOCIÉTÉ BIC

This calculation shows that BIC earned a 12.3% ROE in 2009, indicating that it earned an average of 12.3% on the average shareholders' equity balances. This is down slightly from the previous year's ROE of 12.4%, but not as much as the ROA decreased. Just as with the ROA, this ROE of 12.3% should be compared with the ROE of other similar companies, or with the results of BIC over time. Cross-sectional comparisons of ROE (among different companies) are difficult for the same reason that similar comparisons of ROA are difficult. Differences in the risks involved should result in differences in returns. Differences in the risks cannot, however, always explain large differences in returns, as there are many factors that affect ROE.

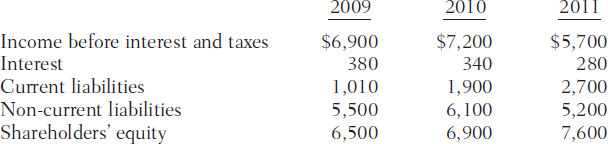

Leverage

Comparing the ROE calculated for BIC with the associated ROA shows that the company, while earning only an 8.6 % return on assets, showed a return of 12.3% on the shareholders' equity. This higher return on equity results from the company's successful use of financial leverage. Financial leverage simply means that some of the funds obtained to invest in assets came from debt holders rather than shareholders. A company that has a larger proportion of debt to shareholders' equity is said to be highly leveraged.

In the case of a totally shareholder-financed company—that is, a company with no debt—the ROE (assuming there is only one class of shares) would equal the ROA. There would be no interest expense and, therefore, the numerators of both ratios would be the same. The denominators would also be the same because the accounting equation (assets = liabilities + shareholders' equity) would be adjusted for the absence of any liabilities (assets = shareholders' equity).

To understand the effects of leverage, consider first the data in Exhibit 12-6 for the fictitious Baker Company, which we assume to be 100% equity-financed. Note that in this example, Baker generates a 15% return on its assets before taxes (earnings before interest and taxes ÷ assets = $150 ÷ $1,000). After the 40% corporate income taxes, this translates into a 9% after-tax return (ROA). Note also that the ROE is the same as the after-tax ROA, because there is no debt and therefore no leverage effect.

The key to financial leverage is the relationship between the after-tax cost of borrowing and the return on assets. When a company borrows money, it invests that money in assets and earns the company's return on assets on that amount. The cost of using those funds is the after-tax cost of borrowing. If the cost to borrow is less than the return that the company can earn on the funds, then the wealth of the company will increase. If it costs the company more to borrow than it can earn on the funds, the wealth of the company will decrease.

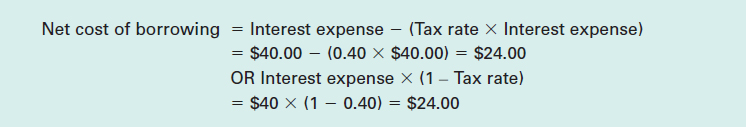

It is necessary to use the after-tax cost of the debt in the comparison, as opposed to just the interest rate, because interest expense, as we saw earlier, is tax deductible and therefore generates tax savings for a company. The taxes saved are the tax rate times the interest expense. The net cost to the company is therefore the interest paid minus the taxes saved. For example, if a company borrows $400 at a rate of 10% and the tax rate is 40%, the net after-tax cost would be as follows:

Case A: 100% Equity-Financed

HELPFUL HINT

The after-tax cost of debt = interest expense × (1 − tax rate), or i × (1 − t).

This equation can be applied either to the interest expense in dollars [i.e., $40 interest expense × (1 − 0.40) = $24 net cost of borrowing, as shown in the example], or to the interest rate in percent [i.e., 10% interest rate × (1 − 0.40) = 6% net cost of borrowing].

When analysts talk about the after-tax cost of borrowing, they normally do it in terms of the rate.

Now consider the data in Exhibit 12-7 for Baker Company, which assumes that the company is only 60% equity-financed. To keep the illustration simple, all liabilities are considered interest-bearing at the rate of 10%. There are two statements of earnings presented, Case B where the earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) is the same as in Case A, $150, and Case C where EBIT has fallen to $75.

In Exhibit 12-7, several things should be noted. The first is that in Case B the ROA (9%) is the same as in the all-equity case in Exhibit 12-6 because the amount of assets has not changed; only the amount of debt has changed. Before interest and tax, the assets should be earning exactly what they would have earned in a 100%-shareholder-financed company. In Case C, when EBIT has fallen by half (from $150 to $75), the ROA has fallen by the same amount (from 9% to 4.5%).

Note that in Case B the ROE (11%) is greater than the ROA (9%). This occurs because the company was able to borrow at an after-tax interest rate that was less than the rate it could earn by investing in assets. The before-tax borrowing rate in Case B is 10%. To adjust this to an after-tax rate, we multiply it by 1 minus the tax rate: 10% × (1 − 0.40) = 6%. Thus, the after-tax cost of debt is 6%, whereas the after-tax return on assets (ROA) is 9%. This increases the ROE for the shareholders.

Case B and Case C: 60% Equity-Financed, Interest Rate 10%

The increase in the ROE in Case B occurs because, when the company borrowed $400 its net cost of borrowing was $24, but it was able to generate $36 (9% × $400) in income from the borrowed funds. The difference is $12, which goes to the shareholders as an incremental return. Therefore, the shareholders earn a $54 (9% of $600) return on the money that they invested, plus the excess return of $12 that is earned on the money that was borrowed, for total earnings of $66. Thus, without any further investment on their part, their percentage return (ROE) over what they could have earned as a 100%-equity-financed company is improved from 9% to 11% ($66 ÷ $600).

In Case C, the ROE (3.5%) is less than the ROA (4.5%). This occurs because the after-tax cost of borrowing at 6% is now greater than the 4.5% return on assets. As a result, the company is incurring the same net borrowing cost of $24 to earn a return of $18 (4.5% × $400). If you are paying more to obtain funds than you can earn by investing them, overall wealth is going to suffer. Note that although the ROA fell by half, the ROE plunged by more than this, from 11% to 3.5%. This is much less than the ROE of 9% in the 100%-equity-financed case; the shareholders would have been better off if the company had not borrowed at all.

This, then, is the advantage and risk of leverage. The shareholders can improve their return (ROE) if the company can borrow funds at an after-tax borrowing rate that is less than the ROA. However, this is a big if. A company that leverages itself is committed to making fixed interest payments to debt holders prior to earning a return for its shareholders. It is betting that the return on assets will be higher than the after-tax cost of its borrowing. If it is wrong and the after-tax cost of borrowing is greater than the ROA, the return to the shareholders (ROE) will fall below what the company could have earned with no debt at all.

If leveraging the company a little is potentially a good thing, as Case B in Exhibit 12-7 illustrated, why not leverage it a lot? In other words, why not borrow funds to finance most of the company's assets? For example, why not have 80% debt and 20% equity in the company?

Case D in Exhibit 12-8 illustrates the kind of return that the company could expect if it had 80% debt financing and the same 10% interest rate and EBIT as Case B in Exhibit 12-7.

A return of 21% is certainly very attractive, compared with the ROE of 11% that could be achieved with a 60% equity-financed company. The problem with this financing strategy is that the riskiness of an investment in Baker Company will be much higher in Case D (with 80% debt and only 20% equity) than in Case B. With high interest charges to be covered, if the company's ROA drops, the ROE will plunge—and may become negative—very rapidly.

The amount of leverage that a company can use is affected by several factors, including the stability of operating cash flows and the types of assets employed by the company. The cost of borrowing for a company increases as the amount of leverage increases. As the company adds more and more debt to its capital structure, it is committing itself to higher and higher fixed interest payments and increasing the risk of not being able to repay the borrowed funds. The increased obligations could perhaps force the company into bankruptcy. Because of the increased risk, as the company increases its level of debt it has to pay higher interest rates. When its borrowing cost starts to equal or exceed its ROA, it will become unattractive to lenders if it seeks further funds.

As we saw in our simple examples, return on equity improves relative to a 100%-equity-financed company when a company begins to use leverage and the ROA is greater than the after-tax cost of borrowing. But as the company continues to increase the amount of debt there is a point where the increasing risk, and hence increasing cost of borrowing, starts to exceed the benefits, and the return on equity starts to decrease. The level of leverage that would maximize the return on equity is sometimes called the company's optimal capital structure. This optimal capital structure exists in theory but is more difficult to determine in the real world. It is true, however, that as you look across industries, different types of businesses have different average levels of debt financing (i.e., leverage). This indicates that, based on the risk characteristics of those industries, the companies in those industries borrow up to the point that they think is beneficial to their shareholders, and no further.

Case D: 20% Equity-Financed, Interest Rate 10%

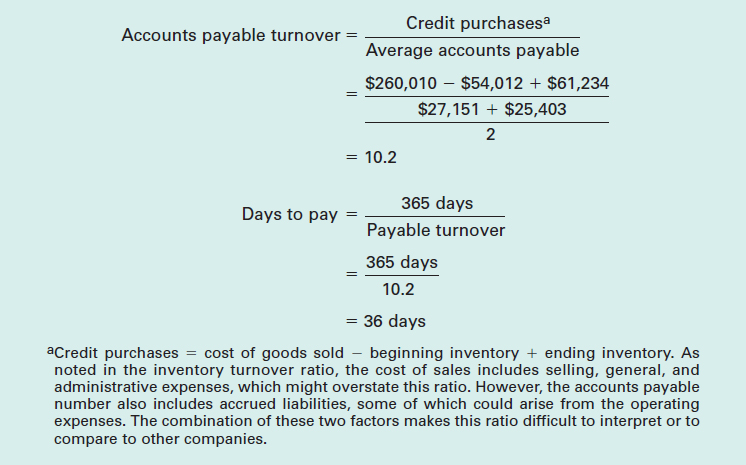

In the notes to its financial statements, BIC discloses that interest rates on its borrowings varied from 2.80% to 11.50%, before taxes. Rates on different borrowings vary depending on the terms and conditions of the debt, as well as the length of time until its maturity and what the market interest rates were at the time the debt was issued. BIC's tax rate was approximately 32.4%, which means its after-tax interest rate ranged from 1.9% to 7.8%. If its ROA was 8.6%, BIC was earning a higher return on its assets than it paid to borrow money. Its ROE of 12.3% illustrates how BIC's use of leverage boosted its ROA into a higher return to its shareholders.

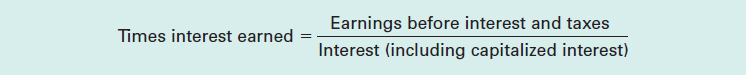

A company's use of leverage can be judged, to some extent, by the difference between its ROE and its ROA, as the hypothetical Baker Company example and BIC's results show. In addition, several other ratios are used to measure the amount of leverage the company employs, as well as how well it uses that leverage. These ratios include the debt to equity ratio and the times interest earned ratio, which are discussed in a later section on solvency.

The following story indicates that if a company gets an appropriate level of leverage and controls costs, the results can be an increase in its share price.

accounting in the news

Cott Has Caught Analysts' Attention

Prospects were not looking good for Cott Corp. in 2009, but the private-label beverage maker's recent transformation has changed some analysts' minds. Cott Corp. shares rose by as much as 7 percent in September 2010 after the company was rated “Buy” in new coverage from Deutsche Bank. Other analysts were also now recommending Cott as a buying opportunity. Their reason is management's return to basics–lean infrastructure, disciplined cost management, a quality low-cost product, healthy customer relations, and a sound balance sheet. In addition, Cott's acquisition of the private-label juice maker Cliffstar Corp. was seen as a significant strategic step forward, providing the company with a better product balance and making it more consistently profitable. Efforts to deleverage the company's balance sheet were also creating value in the short to intermediate term. So, although Cott is not likely to be a fast revenue grower, its improved cost discipline and synergies from Cliffstar should allow the company to generate a steady margin and free cash flow in the future.

Source: David Pett, “Cott Shares Soar,” Financial Post, September 21, 2010. http://business.financial-post.com/2010/09/21/cott-shares-soar/

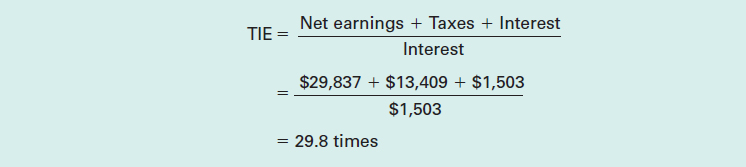

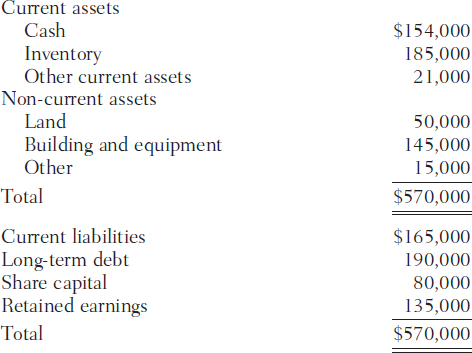

Short-Term Liquidity Ratios

As discussed in Chapter 1, liquidity refers to a company's ability to convert assets into cash to pay liabilities. A basic understanding of the company's short-term liquidity position should result from a consideration of the financial statements, particularly the statement of cash flows, as well as the turnover rates discussed in the next section on activity ratios. Understanding the liquidity position requires knowledge of the leads and lags in the company's cash-to-cash cycle, discussed in Chapters 4 and 5. Managing a company's cash cycle is sometimes also referred to as working capital management. You will recall from earlier chapters that working capital = current assets − current liabilities. In addition, at least three ratios provide quantitative measures of short-term liquidity: the current and quick ratios, and the operating cash flow to short-term debt ratio.

Current Ratio

The current ratio is calculated by comparing the total current assets with the total current liabilities, as follows:

Remember that current assets are those that are going to be converted into cash in the next year (or the company's operating cycle, if it is longer than one year), and current liabilities are going to require the use of cash or other assets in the next year. As such, this ratio should be greater than 1; otherwise, it is difficult to see how the company will remain solvent in the coming year. The rule of thumb for this ratio for most industries is that it should be 1 or more, and, to be conservative, approximately 2. However, the size of this ratio depends on the type of business and the types of assets and liabilities that are considered current. For example, a company that sells primarily on a cash basis and does not have any accounts receivable, like a grocery store, normally has a low current ratio.

One caveat: the current ratio is subject to manipulation by a company at year end. This ratio may not, therefore, be a very reliable measure of liquidity. As a simple example, consider a company that has $100 in current assets and $50 in current liabilities at the end of a given year. Its current ratio would be 2 ($100 ÷ $50). Suppose that $25 of the $100 is in cash and the rest is in inventory. Suppose further that the company uses up all of its $25 in cash to pay $25 of current liabilities at year end. The current ratio becomes 3 ($75 ÷ $25) and the company looks more liquid. However, it is actually less liquid; in fact, it is virtually illiquid in the short term, because it has no cash and must sell its inventory and wait until it collects on the sale of that inventory before it will have any cash to pay its bills. In this case, the current ratio is deceptive.

The current ratios for BIC are as follows:

CURRENT RATIO—SOCIÉTÉ BIC

The current ratio of 3.42 in 2009 is a slight decline from the 3.72 of the previous year. With the ratio above 2 in both years, however, BIC appears able to comfortably handle its short-term obligations. Upon reviewing the components of current assets, we can see that cash and cash equivalents more than doubled over 2008 and is the largest current asset in 2009. There was also an increase in accounts receivable. Despite both these changes, which should increase liquidity, the current ratio decreased. This is because almost all of the current liabilities increased—accounts payable, current borrowings, and other current liabilities. The increase in the current obligations of the company offset the increase in assets and BIC is less liquid than in 2008. Despite this drop, the company appears to be healthy with respect to liquidity.

It is important to note that it is possible for a company to be too liquid—to have too much money invested in assets such as cash and accounts receivable that do not generate any returns for the company. Then again, an increase in cash and cash equivalents might be part of the company's strategy. Maybe the company needs liquid assets for a planned purchase or acquisition early in the next year. Finding answers to questions like these is why it is important for an analyst to understand the business and to talk to management or do additional research before drawing conclusions.

Quick Ratio

One problem with the current ratio is that some assets in the current section are less liquid than others. For example, inventory is usually less liquid than accounts receivable, which are less liquid than cash. In some industries, inventory is very illiquid, because of the long period of time that it may have to be held before sale. Consider, for example, the holding period in the manufacture of 12-year-old Scotch whisky. The current ratio in such cases will not adequately measure the company's short-term liquidity, because the inventory will not be converted into cash for a very long time. In this case, the quick ratio is a better measure of short-term liquidity. It differs from the current ratio in that only the most liquid current assets (cash, accounts receivable, and short-term investments) are included in the numerator. Other current assets, such as inventories and prepaid expenses, are excluded from this ratio. Prepaid expenses do not convert into cash. Instead they used cash in the past and the company will be saving cash in the future because amounts have been paid in advance. The ratio is calculated as follows:

The rule of thumb for this ratio is that it should be approximately 1 or more. A quick ratio of 1 means that the very short-term current assets are equal to the total current liabilities. Again, the desirable level for this ratio depends on the type of industry.

Some judgement is necessary when reviewing BIC's balance sheet to determine which current assets should be included in this ratio. Some of the account titles are not completely clear with respect to understanding how easily the asset could be converted into cash, and do not have accompanying notes to guide the user. The “other current financial assets” are most likely short-term investments, and hence should be included in the quick ratio. Recall from Chapter 6 that financial assets include marketable securities or short-term investments. The “income tax advanced payments” and “other current assets” are more likely similar to prepaids and would not be included in the ratio. The derivative instruments—“Current financial” and “Other”—are more difficult to discern. The quick ratio is intended to be a more stringent test of a company's liquidity than the current ratio; therefore, conservatism would dictate that if we are not certain about an item it is better to exclude it. The “Assets held for sale” will generate cash, but the timing and amount of the cash flow is uncertain, and the amounts are small. It is best to exclude this account as well. Based on those classifications, the calculation is as follows:

QUICK RATIO—SOCIÉTÉ BIC

The quick ratio of 2.50 in 2009 is slightly higher than the quick ratio of 2.27 in 2008, which should not be surprising. Remember that when we discussed the current ratio we noted major increases in BIC's most liquid assets—cash and receivables. The increase in these most liquid of assets is reflected in the increased quick ratio. In both years, the quick ratio is well above the 1.0 rule of thumb amount and brings us back to the concern that perhaps the company has too much invested in assets that do not produce much (if any) return.

Taken together, the current ratio and quick ratio indicate that BIC's liquidity position seems to be healthy but that more information would be useful. Just reviewing these two years illustrates the importance of time-series analyses in understanding a ratio. Going back further than the two years would enable you to see whether a current ratio above 3 and a quick ratio above 2 are normal. Cross-sectional analyses should also be undertaken with other companies that manufacture plastic consumer products.

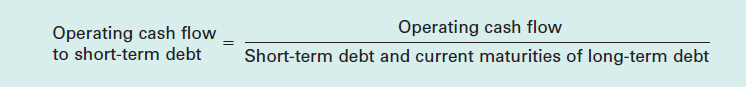

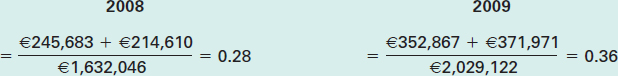

Operating Cash Flow to Short-Term Debt Ratio

In Chapter 5, we discussed the importance of the information on the cash flow statement, how it is prepared, and how it should be interpreted. (You may want to refer to Chapter 5 to refresh your understanding of how to interpret the information on the cash flow statement.) The cash flow statement details the inflows and outflows of cash from operating, financing, and investing activities. The operating cash flow to short-term debt ratio is another measure of the company's ability to meet its short-term debt. It is calculated as follows:

Like the current ratio and the quick ratio, the higher this ratio is, the better the company can meet its short-term debt obligations. For BIC, the results for 2009 and 2008 are as follows:

The operating cash flow to short-term debt ratio of 0.97 in 2009 has increased from the 0.92 of the previous year. The increase indicates that BIC can more comfortably handle its short-term debt obligations; in fact, BIC could almost completely pay off all of its short-term obligations with the operating cash flow generated in the year. Both long-term and short-term debt have increased in 2009 as a result of the acquisitions undertaken, but the cash from operations has also increased, so BIC's ability to meet its short-term obligations continues to look strong.

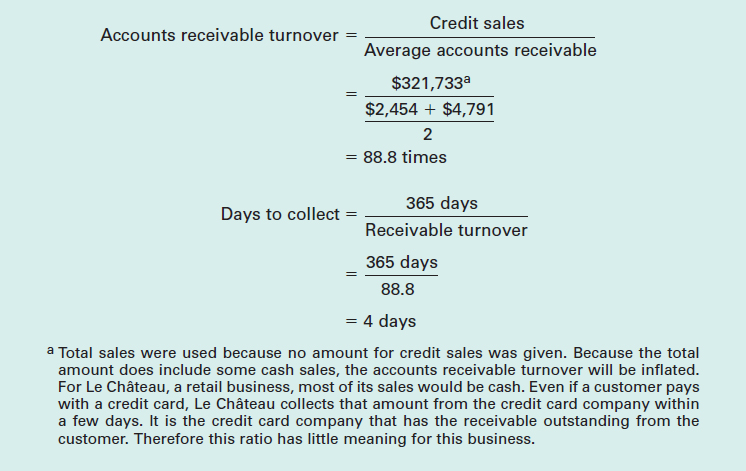

Activity Ratios

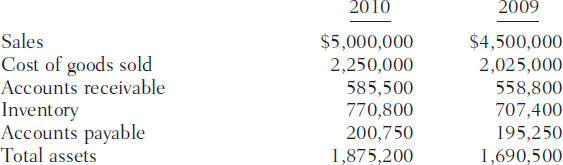

The activity ratios provide additional insight into the major decisions management makes regarding asset use and liquidity. The total asset turnover ratio, discussed earlier as a component of the ROA, is a measure of a company's total asset utilization. There are three other turnover ratios we will discuss to better understand liquidity and assess management's policies concerning accounts receivable, inventory, and accounts payable. They relate to the three policy decisions that were discussed in Chapter 5 regarding the company's cash flow performance. They are the accounts receivable, inventory, and accounts payable turnovers. These ratios provide some quantitative measures of the lead/lag relationships that exist between the revenue and expense recognition and the cash flows related to these three items.

Total Asset Turnover

The total asset turnover ratio measures the dollar amount of sales generated for each dollar invested in assets. Companies acquire assets to generate net earnings, and the first step in generating net earnings is to generate sales. Consider a business that has a single asset that will be used to produce the goods for sale. If management decides to expand by purchasing a second asset, would the sales level double? Perhaps the sales might not double immediately if the second machine were not yet operating at full capacity, but if the company wants to maintain the same level of efficiency its objective would be to have the sales level double. By examining the ratio of sales to assets, the asset turnover ratio, we can assess how efficiently the company is using its assets. This is a different measure than merely comparing net income to see if it has doubled, because other factors such as cost control influence net income. By differentiating between the effect on sales versus net income, managers and analysts can determine if the company's difficulties lie in generating sales, or in controlling costs. The solutions to those two problems are different, so determining which one is the source of the problem is important for effective management.

As calculated for ROA (on page 801), the total asset turnover for BIC in 2009 was 0.85, down slightly from 0.87 in 2008. It appears that with BIC's recent acquisitions, its efficiency has fallen slightly. Trend analysis would be useful to determine if the decrease is due solely to the acquisitions or is a longer term concern.

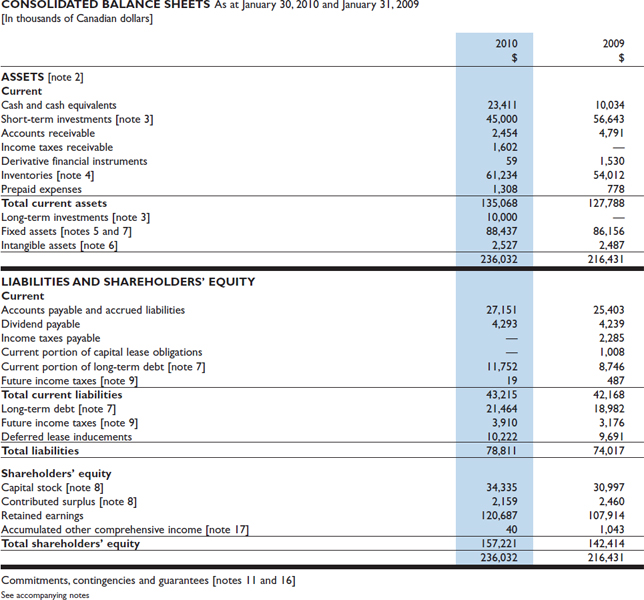

Accounts Receivable Turnover

The accounts receivable turnover ratio attempts to provide information about the company's accounts receivable policy. This ratio was introduced in Chapter 6, when the management of accounts receivables and other short-term liquid assets was discussed. This ratio measures how many times during a year the accounts receivable balance turns over—that is, how many times old receivables are collected and replaced by new receivables. It is calculated as follows:

When data from financial statements are used, the assumption is usually made that all sales were on account, because there is usually no information in the financial statements about the percentage of credit sales (or sales on account) versus cash sales. If the turnover ratio were being prepared for internal use by management, this type of information would be available and only credit sales would be used when calculating this ratio. It is probable that most of BIC's sales are credit sales, since it sells its products to retailers and wholesale distributors. Companies that sell directly to the public, like grocery stores, tend to sell primarily on a cash basis and hence have few (if any) credit sales. Additionally, the ratio should only include receivables related to credit sales, often referred to as trade receivables, and not other miscellaneous receivables (for example, receivables related to expected tax refunds or advances to employees). The description in BIC's balance sheet is “trade and other receivables,” and although the breakdown is available in the notes, for simplicity we will assume they are all related to sales.

Using BIC's data, the ratio is as follows:

ACCOUNTS RECEIVABLE TURNOVER—SOCIÉTÉ BIC