chapter 8

CAPITAL ASSETS—TANGIBLE AND INTANGIBLE

HOW ARE CAPITAL ASSETS VALUED?

Units-of-Activity or Production Method

Accelerated or Declining-Balance Method

Recording Depreciation Expense

CHANGES IN DEPRECIATION ESTIMATES AND METHODS

ADDITIONAL EXPENDITURES ON CAPITAL ASSETS DURING THEIR LIVES

WRITEDOWNS AND DISPOSALS OF PROPERTY, PLANT, AND EQUIPMENT

Patents, Trademarks, and Copyrights

Comprehensive Example of Capital Asset Disclosures

STATEMENT ANALYSIS CONSIDERATIONS

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

- Describe the valuation methods for capital assets.

- Identify the types of asset acquisition costs that are usually capitalized.

- Explain the purpose of depreciation and implement the most common methods of depreciation, including capital cost allowance.

- Identify the factors that influence the choice of depreciation method.

- Describe and implement changes in depreciation estimates and methods.

- Account for the disposal and writedown (impairment) of capital assets.

- Describe and implement the depreciation method used most frequently for natural resources.

- Explain the accounting difficulties associated with intangible assets.

- Depreciate intangible assets, where appropriate.

- Calculate the return on assets ratio and discuss the potential implications of the results.

A Canadian Staple's Capital Costs

Nine out of 10 adult Canadians shop at Canadian Tire every year, and 40 percent of Canadians shop there every week, the company website boasts. In fact, the location of Canadian Tire's 475 retail stores allows it to serve more than 90 percent of the Canadian population. It is no surprise, then, that this market reach translates into a significant amount of capital assets, both tangible and intangible. Indeed, the company logo, the instantly recognizable red triangle with the green maple leaf, is a significant intangible asset for the company. However, that specific asset does not have any capitalized asset value on Canadian Tire's balance sheet.

According to Huw Thomas, Canadian Tire's Executive Vice-President, Financial Strategy and Performance, the logo would be on the balance sheet “if we had done a lot of work to create that triangle as a brand.” Instead, the creation of the brand's value happened over a long period, and Canadian Tire did not capitalize any costs associated with that process. “If we had,” Mr. Thomas continues, “we would have the potential for the creation of further intangibles, because the brand obviously has significant value. But current accounting (and IFRS) doesn't have you carry the value of assets like that on your balance sheet.” Intangible assets that have been purchased, however, are carried on the balance sheet. For example, Canadian Tire's acquisition of the Mark's Work Wearhouse chain includes the capitalization of intangibles, such as the company's well-established brand name. All of the goodwill that appears on the balance sheet has been gained through acquisitions, Mr. Thomas says.

On a large acquisition such as Mark's Work Wearhouse, the company calculates the fair value of the various assets it has acquired, including any trademarks. “You create models as to what that trademark might be worth, looking into the future, and then the difference between the total amount that you've paid, less the fair value of the net assets you've acquired, represents goodwill,” explains Mr. Thomas. “That becomes an asset that sits on the balance sheet, and every year you have to assess whether the goodwill amount has become impaired.” The company would do an impairment assessment for any asset on the balance sheet, whether intangible or tangible, he adds.

Canadian Tire owns 70 percent of the land and buildings for the main stores in its network. The costs to develop a new store location include acquiring the land and the legal costs associated with that purchase, as well as the physical construction of the store itself. As portions of the building are completed, progress payments for the construction are capitalized, Mr. Thomas explains. During the construction period, the company also capitalizes interest costs associated with funding the land purchase, and project costs for the building. “We have a set of specific internal guidelines around what can be capitalized and what can't be,” says Mr. Thomas, “and that is consistent with GAAP.”

“There are various differences between current accounting under Canadian GAAP and IFRS,” Mr. Thomas continues. These differences include the choice to record property and equipment at fair values (under a revaluation model) or at cost, and the IFRS requirement to separately account for and depreciate significant parts of a property and equipment asset. “As IFRS requires borrowing costs that are directly attributable to the construction of a qualifying asset to be capitalized as part of the cost of that asset,” concludes Mr. Thomas, “the move to IFRS will not have any significant impact on our accounting for real estate development projects.”

Our opening story describes some difficulties associated with recording and reporting capital assets at Canadian Tire Corporation, which has significant sums invested in the capital assets that form its extensive retail network and the distribution system (warehouses, trucks, etc.) that supports it. The main accounting issues for these assets include determining the amounts to be recorded as the costs of the assets, how long the company expects to benefit from the assets' use, and how the costs should be transferred to expense during these periods. Each of these issues has significant implications for the amounts that will be reported on both the company's balance sheet and its statement of earnings.

This chapter will discuss the measurement, recording, and reporting issues related to capital assets. In the previous two chapters, we studied current assets whose value would be realized within one year (or the operating cycle). In this chapter, we discuss capital assets—assets with lives longer than a year (or the operating cycle) that are used in the company's operations to generate revenue. Long-term investments that also have lives longer than a year are discussed briefly in Appendix B at the end of the text.

Of the capital assets that we are going to study, property, plant, and equipment are the most recognizable. These are a type of non-current asset called tangible assets, which are usually defined as those assets with some physical form. (“Tangible” comes from the Latin word meaning “to touch.”) In other words, you can usually see these assets and touch them. Intangible assets, on the other hand, are non-current assets that are associated with certain legal rights or privileges the company has, such as patents, trademarks, leases, and goodwill.

In the sections that follow, the recognition and valuation issues for capital assets are discussed, much as they were for current assets. Because of the long-term nature of these assets, it is important to address the issue of how to show their effect on the statement of earnings as their cost is expensed over time. The expensing of an asset's cost over time is referred to as depreciation (for tangible assets) and amortization (for intangible assets).

USER RELEVANCE

Capital assets provide the underlying infrastructure of many companies. They include the real estate, buildings, equipment, vehicles, computers, patents, and so on that companies need to carry out their day-to-day operations. They often require a substantial outlay of funds to acquire, which means that companies will often secure long-term mortgages or other forms of debt to finance them. Another common way to acquire long-lived assets is to lease them. You may find some assets on a statement of financial position labelled as “assets under capital leases.”

Because of their importance to business operations, their high costs, and their long lives, the role that capital assets play in a company's success needs to be understood by financial statement users. Users need to monitor the assets' lives so that they can anticipate the future outflows of cash to replace them. They need to know what methods a company has chosen to depreciate its assets, and what impact those methods have on the statement of earnings. They also need to understand that the value carried on the balance sheet for capital assets represents a future benefit that the company expects to earn from using the assets. If the company did not expect to earn the carrying values through its use of the assets, it would be required to write them down (i.e., reduce the carrying values). In most instances, companies expect to earn amounts that are significantly higher than the carrying values of their capital assets.

This chapter will provide you, as a user, with the necessary background information on capital assets so that you can better understand the impact that these assets have on the financial statements.

CAPITAL ASSET RECOGNITION

Assets must have probable future value for the company. The company must also have the right to use them and must have acquired that right through a past transaction. When a company buys a capital asset, both of these conditions exist: it has the right to use the asset and a transaction has occurred. Therefore, the only asset criterion that merits further discussion is the probable future value, which takes at least two forms. Capital assets are used, first and foremost, to generate revenues, usually by producing products, facilitating sales, or providing services. Therefore, the future value is represented by the cash that will eventually be received from the sales of products and services. This type of value is sometimes referred to as value in use. Because of the long-term nature of capital assets, these cash flows will be received over several future periods.

The second source of value for capital assets is their ultimate disposal value. Many capital assets are used until the company decides to replace them with a new asset. For example, a business may use a truck for four or five years and then trade it in for a new one. This type of value is called residual value (or resale value) and can be very important, depending on the type of asset.

Value in use is normally the most appropriate concept for capital assets because companies usually invest in them to use them, not to sell them. Residual value cannot, however, be totally ignored, because it represents the asset's expected value at the end of its use. In Chapter 2, you were introduced to how we use residual value to determine the amount of depreciation that should be recorded.

The difficulty with the value in use concept for capital assets is that the future revenue (and ultimately income) that will be generated by using the asset is inherently uncertain. The company does not know to what extent the demand for its products or services will continue into the future. It also does not know what prices it will be able to command for its products or services. Other uncertainties relate to technology. Equipment can become obsolete as a result of technological change. New technology can give competitors a significant advantage in producing and pricing products. Technological change can also reduce or eliminate the need for the company's product. Consider a manufacturer of cassette tapes when CDs came on the market, or a videotape or VCR manufacturer with the advent of DVDs.

Uncertainty about the asset's value in use also gives rise to uncertainty about its eventual residual value, since the ultimate residual value will depend on whether the asset will have any value in use to the ultimate buyer. There may also be a question of whether a buyer can even be found. Equipment that is made to the original buyer's specifications may not have much residual market value because it may not meet the needs of other potential users.

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 1

Describe the valuation methods for capital assets.

HOW ARE CAPITAL ASSETS VALUED?

In the sections that follow, the discussion is limited to valuation issues regarding property, plant, and equipment, which are similar to those relating to other non-current capital assets. At the end of the chapter, specific concerns and issues regarding natural resources and intangible assets are discussed.

In Canada, property, plant, and equipment are usually valued at historical cost, with no recognition of any other value unless the asset's value becomes “impaired” (i.e., the value of the estimated future cash flows is less than the current carrying value). IFRS allows the recognition of changes in the market values of property, plant, and equipment and you may come across companies that are using market value for their capital assets. Before Canadian practice is discussed in detail, several possible valuation methods will be considered.

Historical Cost

In a historical cost valuation system, the asset's original cost is recorded at the time of acquisition. Changes in the asset's market value are ignored in this system. During the period in which the asset is used, its cost is expensed (depreciated) using an appropriate depreciation method (discussed later in this chapter). Market values are recognized only when the asset is sold. The company then recognizes a gain or loss on the sale, which is determined by the difference between the proceeds from the sale and the net book value (or carrying value) of the asset at the time of sale. The net book value or carrying value is the original cost less the portion that has been charged to expense in the form of depreciation. This net book value is sometimes called the depreciated cost of the asset.

Market Value

Another possible valuation method records capital assets at their market values. There are at least two types of market values: replacement cost and net realizable value.

Replacement Cost

In this version of a market valuation system, the asset is carried at its replacement cost—the amount that would be needed to acquire an equivalent asset. At acquisition, the historical cost is recorded because this is the replacement cost at the time of purchase. As the asset is used, its carrying value is adjusted upward or downward to reflect changes in the replacement cost. Unrealized gains and losses are recognized for these changes. The periodic expensing of the asset, in the form of depreciation, has to be adjusted to reflect the changes in the replacement cost. For example, if the asset's replacement cost goes up, the depreciation expense will also have to go up, to reflect the higher replacement cost. A realized gain or loss is recognized upon disposal of the asset. The amount of the gain or loss is determined by the difference between the proceeds from the sale and the depreciated replacement cost at the time of sale.

Net Realizable Value

With a net realizable value system, assets are recorded at the amount that could be received by converting them to cash; in other words, from selling them. During the periods when the assets are being used, gains and losses are recognized as their net realizable values change over time. Depreciation in this type of system is based on the net realizable value and is adjusted each time the asset is revalued. The recognition of a gain or loss at the time of sale should be for a small amount, since the asset should be carried at a value close to its resale value at that date. This system is not consistent with the notion of value in use, which assumes that the company has no intention of selling the asset. IFRS allows this valuation system. As Canadian companies adapt to IFRS, companies may opt to use net realizable value.

The word “market” must be used with some care. The preceding discussions assume that both the replacement market and the selling market are the markets in which the company normally trades. There are, however, special markets if a company has to liquidate its assets quickly. The values in these markets can be significantly different from those in normal markets. As long as the company is a going concern, these specialty markets are not appropriate for establishing values for the company's assets. On the other hand, if the company is bankrupt or going out of business, these specialty markets may be the most appropriate places to obtain estimates of the assets' realizable market values. It might be difficult to determine a market value under either method if the assets are very specialized.

INTERNATIONAL PERSPECTIVES

Reports from Other Countries

While most countries value property, plant, and equipment at historical cost, a few (such as France, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom) have allowed revaluations of these assets based on current replacement costs.

These revaluations are seldom made in France, because they would be taxable. In the UK, on the other hand, such revaluations are quite common. The increase in the value of the assets that occurs under the replacement cost valuation is not usually considered part of net income, but (like “other comprehensive income”) is recorded directly in the shareholders' equity section of the statement of financial position, in an account called a revaluation reserve.

What Is Canadian Practice?

In Canada, most capital assets are valued at their depreciated historical cost (the remaining portion of their original acquisition cost). During the periods of use, the asset's cost is expensed using a depreciation method that is rational, systematic, and appropriate to the asset.

With the adoption of IFRS, some companies may decide to change to the market values for their capital assets. Under this valuation method, the assets are revalued every three or four years. During the intervening years, the assets are depreciated using the same depreciation methods that are used under the cost method. A detailed description of this method is covered in intermediate financial accounting courses.

Under both historical cost and net realizable value, an asset cannot be valued at more than the amount that can be recovered from it. The net recoverable amount is the total of all the future cash flows related to the asset, without discounting them to present values. If it is ever determined that an asset's carrying value exceeds its net recoverable amount, the carrying value must be written down and the difference recognized as an impairment loss.

The accounting standards for private sector enterprises allow only the historical cost method for valuing capital assets.

Ethics in Accounting

ethics in accounting

The ability to control the timing of a writedown of property, plant, and equipment provides management with an opportunity to “manage” or manipulate earnings. The issue of earnings management, as described earlier in this text, has been studied by many researchers in an attempt to demonstrate its existence and to estimate its effects. In one study, Belski, Beams, and Brozovsky had business students respond to six situations that involved ethical issues. As the following excerpt from the study shows, the intent of the described actions influenced the students' perception of the potential level of ethical actions:

The study found that the intent of the earnings management matters. That is, subjects find that managers engaging in earnings management that was deemed opportunistic or selfish were considered more unethical (less ethical) than earnings management behaviour aimed at increasing firm contracting efficiency. Additionally the study found that the method of the manipulation was also important. Accounting estimate manipulations were considered the least ethical followed by economic operating decisions. Changes in accounting method were considered the least unethical.1

The writedown (or write-off) of property, plant, and equipment or the change in the useful life or estimated residual value of depreciable assets are ways in which management might attempt to manipulate earnings. The reader of financial statements must be aware of this possibility.

1. W.H. Belski, J.D. Beams, and J.A. Brozovsky, “Ethical Judgments in Accounting: An Examination on the Ethics of Managed Earnings,” Journal of Global Business 2, no. 2 (2008), pp. 59–68.

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 2

Identify the types of asset acquisition costs that are usually capitalized.

Capitalizable Costs

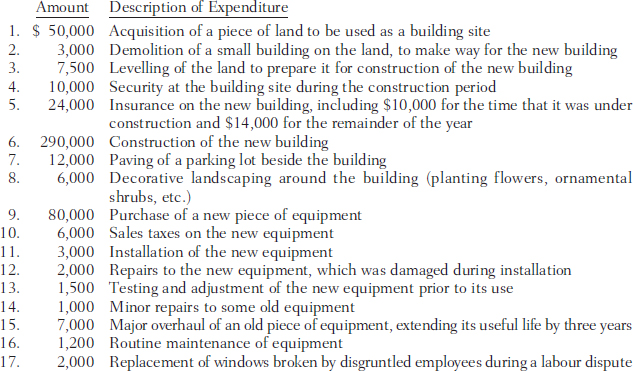

At the date of acquisition, the company must decide which costs associated with the purchase of the asset should be included as a part of the asset's cost, or capitalized. The general guideline is that any cost that is necessary to acquire the asset and get it ready for use is a capitalizable cost. Any cost incurred that is not capitalized as part of the asset cost would be expensed in the period of the purchase. The following is a partial list of costs that would normally be capitalized (i.e., included in the cost of a capital asset).

EXAMPLES OF CAPITALIZABLE COSTS

Purchase price (less any discounts)

Direct taxes on the purchase price

Interest cost (on self-constructed assets)

Legal costs associated with the purchase

Shipping or transportation costs

Preparation, installation, and set-up costs

The reason for capitalizing ancillary costs (such as taxes on the purchase price, legal costs associated with the purchase, shipping or transportation costs, and preparation, installation, and set-up costs) is the matching principle. If these related costs are recorded as part of the asset's cost, they will be charged to expense in future periods, as depreciation, in order to match them to the revenues that are generated while the asset is being used.

The determination of which costs appropriately belong in an asset account is not always easy. For example, consider a company purchasing new equipment. The salaries of the employees who develop the specifications for the new equipment, negotiate with potential suppliers, and order the equipment are normally not included in the acquisition cost. This is true even though the time spent by these employees is necessary to acquire the asset. On the other hand, if a significant amount of employee time is required to install the new equipment, these employees' wages are usually recorded as part of the cost of the equipment. The costs associated with clearing land in preparation for constructing a new building are usually added to the land account. The cost of digging the hole for the building's foundation, on the other hand, is usually added to the building account.

Land is a unique capital asset. Even after it has been used by a company for several years, land will still be there to be used indefinitely in the future. Therefore, unlike other capital assets, its cost is not depreciated. Consequently, assigning costs to land means that those costs will remain on the statement of financial position forever; they will not appear on the statement of earnings in the future, as depreciation expense.

Related to land is another category of capital assets that are commonly referred to as land improvements. The term land improvements refers to things done to the land to improve its usefulness, but which will not last forever. Examples include the installation of fencing, parking lots, lighting, and walkways. It is important to distinguish these types of items from the land itself, because the cost of these land improvements must be depreciated over their expected useful lives.

Deciding which costs to capitalize is also often influenced by income tax regulations. For tax purposes, companies would like to expense as many costs as possible, in order to reduce their taxable income and save on taxes. Capitalizing costs, on the other hand, means that companies have to wait until the assets are depreciated before the costs can be deducted for tax purposes. There is, therefore, an incentive to expense rather than to capitalize costs that are only indirectly related to the acquisition of assets, and companies may decide to expense costs for financial reporting purposes to bolster their arguments that the costs are expenses for tax purposes.

The materiality criterion also plays a part in which costs are capitalized. Small expenditures related to the purchase of an asset may be expensed rather than capitalized, because expensing them is simpler and adding small amounts to the cost of the asset would not change it significantly.

Basket Purchases

Sometimes a company acquires several assets in one transaction. This is called a basket purchase. For example, when a forest products company buys timberland, it acquires two distinct assets—land and timber. Therefore, the price paid for the timberland must be divided between the land and the timber, on the basis of their relative fair values at the time of acquisition. This is necessary for three reasons: first, full disclosure requires that each important type of asset be reported separately on the statement of financial position; second, assets that have different rates of depreciation have to be recorded separately in the accounts; and third, some assets, such as land, are not depreciated at all. Suppose that the timberland's purchase price was $880,000 and the fair values of the land and timber were assessed at $250,000 and $750,000, respectively. (Sometimes when assets are acquired in a group it is possible to negotiate a price that is less than the sum of the selling price of the individual assets.)

In this case, the fair value of the land is 25% ($250,000 ÷ $1,000,000) of the total fair value. Therefore, 25% of the total purchase price should be assigned to the land, and the remaining 75% of the cost should be assigned to the timber. Accordingly, a cost of $220,000 (0.25 × $880,000) would be recorded in the land account, and the remaining $660,000 (0.75 × $880,000) of the purchase price would be recorded in the timber account. In the case of timberland, splitting the cost has significant implications for the company because the cost of the land will not be depreciated but the cost of timber will be expensed through depreciation as the timber is harvested.

Another example of a basket purchase is the purchase of a building. Part of the real estate cost must be allocated to the land on which the building is sitting and the remainder to the building. If the building includes various pieces of equipment or furniture, part of the purchase cost will have to be allocated to these items as well. Management's bias in favour of higher income would motivate them to allocate more of the overall cost to the land, and less to the building and other depreciable assets. However, their conflicting desire to pay less income tax would motivate them to allocate a smaller portion of the total cost to the land, and a larger portion to the building and other amortizable assets.

IFRS also requires companies to look within assets such as buildings to see if there are any component parts of the asset that have useful lives that are different from the asset as a whole. For example, assume a company determines that the cost of a building is $750,000 and its useful life is expected to be 35 years. The roof of the building, however, may only last for 15 years. The company should allocate a portion of the original cost of $750,000 to the roof, list the roof as a separate asset and depreciate it over the 15 years.

Interest Capitalization

The issue of interest capitalization deserves special consideration. Companies often borrow money to finance the acquisition of a large capital asset. The interest paid on the borrowed money is sometimes capitalized, by including it in the capital asset account rather than recording it as an expense. This is often a major issue for companies that construct some of their own capital assets. For example, some utility and natural resource companies construct their own plant assets. In addition to the costs incurred in the actual construction of these assets (including materials, labour, and overhead), these companies may also incur interest costs if they borrow money to pay for the construction.

Under IFRS, companies can capitalize interest costs for capital assets that are constructed or acquired over time, if the costs are directly attributable to the acquisition. The interest costs can only be capitalized until the capital asset is complete and ready for use, however. Once the asset is ready to use, all subsequent interest costs must be expensed through the statement of earnings.

For assets that are purchased rather than constructed, interest costs are usually not capitalized. The time between acquisition and when it is ready to use is usually too short to make interest capitalization meaningful.

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 3

Explain the purpose of depreciation and implement the most common methods of depreciation, including capital cost allowance.

DEPRECIATION CONCEPTS

Depreciation is a systematic and rational method of allocating the cost of capital assets to the periods in which the benefits from the assets are received. This matches the asset's expense in a systematic way to the revenues that are earned in using it, and therefore satisfies the matching principle, described in Chapter 2. The company does not show the capital asset's entire cost as an expense in the period of acquisition, because the asset is expected to help generate revenues over multiple future periods. Matching some portion of a capital asset's cost to the company's revenues, along with its other expenses, results in a measurement of net profit or loss during those periods.

To allocate the expense systematically to the appropriate number of periods, the company must estimate the asset's useful life—that is, the periods over which the company will use the asset to generate revenues. The company must also estimate what the asset's ultimate residual value will be at the end of its useful life. It does this by looking at the current selling price of similar assets that are as old as the asset will be at the end of its useful life. Once the asset's useful life and residual value have been estimated, its depreciable cost (acquisition cost minus the residual value)—the portion of the asset's cost that is to be depreciated—must then be allocated in a systematic and rational way to the years of useful life. (The term “acquisition cost” refers here to the total capitalized cost of the asset.)

It is important to note that depreciation, as used in accounting, does not refer to valuation. Rather, it is a process of cost allocation. While it is true that a company's capital assets generally decrease in value over time, depreciation normally does not attempt to measure this change in value each period.

The choice of which method to use to allocate a cost across multiple periods will always be somewhat arbitrary. Accounting standards require that the depreciation method reflect the pattern of the economic benefits that are expected to be realized from using the asset. Simply stated, the chosen depreciation method must be a rational and systematic method that is appropriate to the nature of the capital asset and the way it is used by the enterprise. In addition, the method of depreciation and estimates of the useful life and residual value should be reviewed on a regular basis.

Even though accounting standards do not specify which depreciation methods may be used, most companies use one of the methods discussed in the next section.

Depreciation Tutorial

DEPRECIATION METHODS

As accounting standards developed, rational and systematic methods of depreciation capital assets were created. The simplest and most commonly used method (used by more than 50 percent of Canadian companies) is the straight-line method (illustrated in Chapter 2), which allocates the asset's depreciable cost evenly over its useful life. Many accountants have argued in favour of this method for two reasons. First, it is a very simple method to apply. Second, for assets that generate revenues evenly throughout their lives, it properly matches expenses to revenues. It might also be argued that, if an asset physically deteriorates evenly throughout its life, then straight-line depreciation would reflect this physical decline.

A second type of depreciation method recognizes that the usefulness or benefits derived from some capital assets can be measured fairly specifically. This method is usually called the units-of-activity or production method. Its use requires that the output or usefulness that will be derived from the asset be measurable as a specific quantity. For example, a new truck might be expected to be used for a specific number of kilometres. If so, the depreciation cost per kilometre can be calculated and used to determine each period's depreciation expense, based on the number of kilometres driven during that accounting period.

For certain assets, the decline in their revenue-generating capabilities (and physical deterioration) does not occur evenly over time. In fact, many assets are of most benefit during the early years of their useful lives. In later years, when these assets are wearing out, require more maintenance, and perhaps produce inferior products, the benefits they produce are much lower. This scenario argues for more rapid depreciation in the early years of the asset's life, when larger depreciation expenses will be matched to the larger revenues produced. Methods that match this pattern are known as accelerated or declining-balance methods of depreciation.

A fourth, but rarely used, depreciation method argues that for some assets the greatest change in usefulness and/or physical deterioration takes place during the last years of the asset's life, rather than in the first years. Capturing this pattern requires the use of a decelerated or compound interest method of depreciation. Although this type of depreciation method is not used much in practice, it is conceptually consistent with a present-value method of asset valuation.

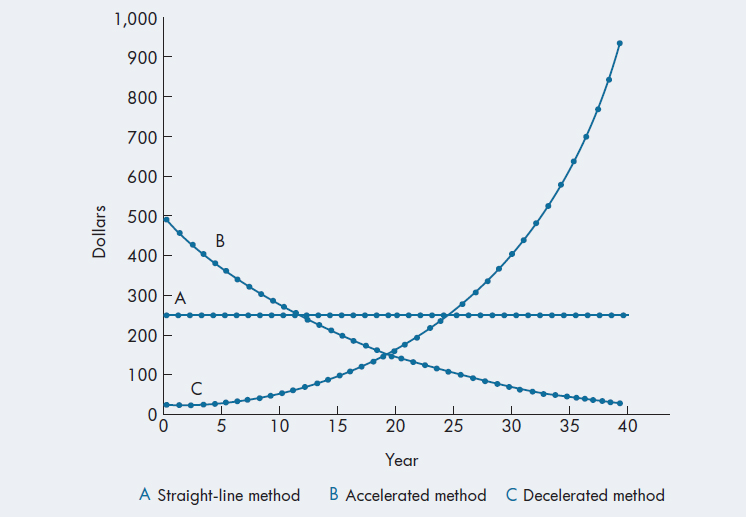

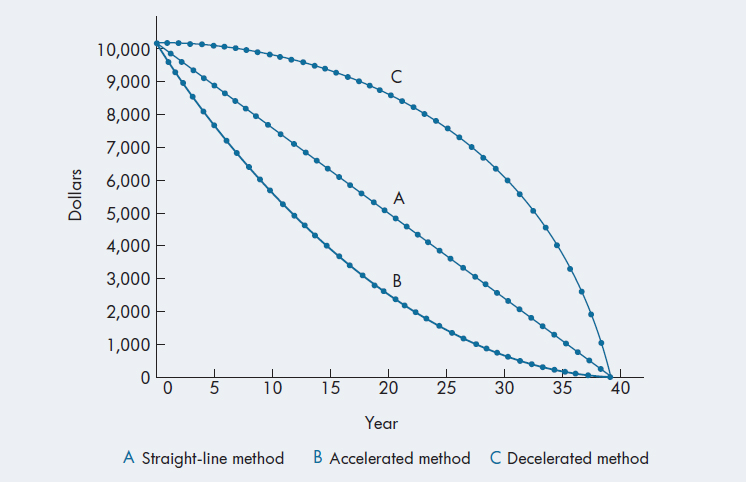

Exhibit 8-1 illustrates the pattern of depreciation expense under the three methods with predictable methods of depreciation: straight-line, accelerated, and decelerated (these methods are discussed in detail later). Exhibit 8-2 illustrates the pattern of decline in an asset's carrying value under the same methods. The graphs are based on a $10,000 original cost, a 40-year useful life, and zero residual value.

EXHIBIT 8-1 ANNUAL DEPRECIATION EXPENSE

EXHIBIT 8-2 ASSET CARRYING VALUE

In Exhibit 8-1, you can see that with the straight-line method, the depreciation expense for each period is the same; this produces the even (or straight-line) decline in the asset's carrying value shown in Exhibit 8-2. With the accelerated method, Exhibit 8-1 shows that the annual depreciation expense is higher in the earlier years; this causes a faster decline in the net carrying value during the earlier years of the asset's life, as seen in Exhibit 8-2. For the decelerated method, on the other hand, Exhibit 8-1 shows that the depreciation expense is much lower in the earlier years; this results in a much slower decline in the asset's carrying value during the earlier years of the asset's life, as shown in Exhibit 8-2. However, although the pattern of recognition is different, the total amount of expense taken over the asset's life is the same for all methods. This is evidenced by the fact that, as shown in Exhibit 8-2, all the methods start with a carrying value of $10,000 and end with a carrying value of zero (indicating that each method transfers the entire depreciable cost to expense during the asset's life).

Note that Exhibits 8-1 and 8-2 do not show the units-of-activity or production method because there is usually no consistent or predictable pattern with this method, since the annual amount of depreciation expense depends on the actual usage each year.

To now illustrate each of the depreciation methods, we will use the following example:

EXAMPLE USED FOR DEPRECIATION CALCULATIONS

A company buys equipment for $50,000; the equipment has an estimated useful life of five years and an estimated residual value of $5,000. The total amount to be depreciated over the equipment's life—its depreciable cost—is therefore $45,000 (i.e., $50,000 − $5,000).

Straight-Line Method

The most commonly used method of depreciation for financial reporting is the straight-line method, which assumes that the asset's cost should be allocated evenly over its life. Using our example, the depreciation would be calculated as in Exhibit 8-3.

Depreciation expense of $9,000 is recorded each year for five years, so that by the end of the asset's useful life the entire depreciable cost of $45,000 (i.e., $50,000 − 5,000) is expensed and the carrying value of the asset is reduced to its residual value of $5,000.

Even though the straight-line method can be described by the estimated useful life and estimated residual value, it is sometimes characterized by a rate of depreciation. The rate of depreciation with the straight-line method is determined by taking the inverse of the number of years, 1/N, where N is the number of years of estimated useful life. In the case of the asset in the example, depreciating it over five years means a rate of 1 ÷ 5, or 20% per year. This is referred to as the straight-line rate. Note that 1 ÷ 5 or 20% of the depreciable cost of $45,000 is $9,000 per year.

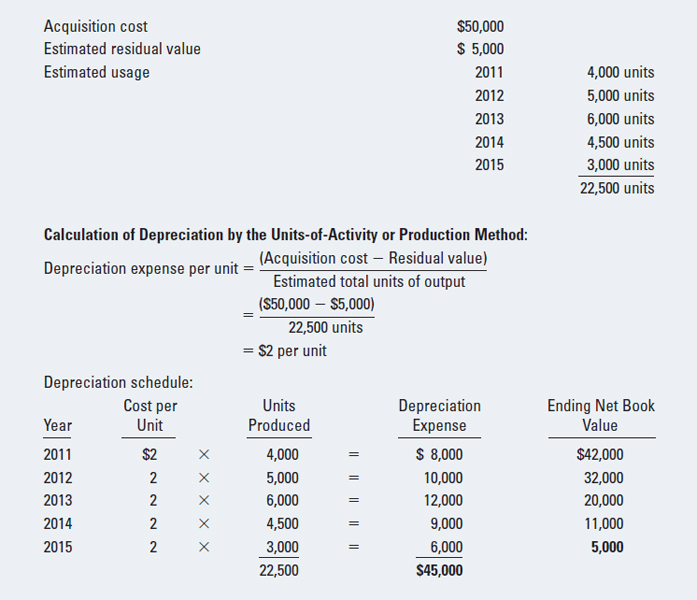

Units-of-Activity or Production Method

Another method to calculate depreciation uses as its basis the assumption that benefits from a capital asset are directly related to the output or use of that asset. Note that the straight-line method of depreciation assumes that benefits derived from capital assets are related to time, disregarding how much the assets are actually used during each period. In contrast, the units-of-activity or production method relates benefits to actual usage, which means that it best satisfies the matching principle.

EXHIBIT 8-3 STRAIGHT-LINE METHOD OF DEPRECIATION

Under the units-of-activity method, the asset's useful life is estimated and expressed as units of output or activity, rather than years of service. For example, trucks can be depreciated using this method if their expected useful lives can be expressed in kilometres driven or hours used. Machinery used in manufacturing products may have an expected useful life based on the total number of units of output. Depreciation expense is then determined by calculating the depreciation cost per unit, and multiplying this cost per unit by the actual number of units produced or used for the period. The formula for calculating depreciation expense per unit for the units-of-activity or production method is as follows:

To calculate the depreciation expense for the period, simply multiply this per-unit cost by the total number of units produced or used during the period. Exhibit 8-4 illustrates this method using our previous example.

EXHIBIT 8-4 UNITS-OF-ACTIVITY OR PRODUCTION METHOD OF DEPRECIATION

Accelerated or Declining-Balance Method

The accelerated method of depreciation assumes that most of the benefits from the asset's use are realized in the early years. Most accelerated methods are calculated by multiplying the asset's carrying value by a fixed percentage. Because the carrying value (cost less accumulated depreciation) decreases each year (since the accumulated depreciation increases each year by the amount of the depreciation expense recorded), the resulting amount of depreciation expense decreases each year.

The formula for calculating accelerated or declining-balance depreciation follows:

(Acquisition cost − Accumulated depreciation at beginning of period) × Depreciation % = Depreciation expense

The percentage that is used in these calculations is selected by management based on their judgement of how quickly the asset's usefulness will decline. The faster the expected decline, the higher the percentage selected. Different types of capital assets will be assigned different percentages. A capital asset with a relatively long expected useful life (such as a building) would have a fairly small percentage (such as 5% or 10%), while a capital asset with a relatively short expected useful life (such as equipment) would have a larger percentage (such as 20% or 30%).

One method of establishing the percentages to be used is the double-declining-balance method. With this method, the percentage selected is double the straight-line rate. Thus, using the example shown in Exhibit 8-3, the acquisition cost of an asset with a five-year expected useful life would be depreciated over five years on a straight-line basis (that is, 1/5 or 20% per year), but would be depreciated at 40% using the double-declining-balance method. However, even though this method appears to be based on fairly concrete numbers, it must be remembered that the 40% rate is very questionable (since the 20% is based on an estimate and doubling it is arbitrary).

Exhibit 8-5 shows the calculation under double-declining-balance depreciation using our ongoing example. Note that, under this method, the asset's residual value does not directly enter into the calculation of the depreciation expense. Instead, the estimated residual value serves as a constraint; the final net book value should equal the residual value. In the example in Exhibit 8-5, this means that in 2015 the company has to record $1,480 of depreciation expense, to reduce the asset from its net book value of $6,480 at the end of 2014 to its residual value of $5,000 at the end of 2015.

HELPFUL HINT

When using declining-balance depreciation, remember that the residual value is ignored until the final year of the asset's life. At that point, you depreciate whatever amount will reduce the asset's net book value to its residual value.

In this case, only a small amount of depreciation had to be taken in the final year. In other cases, however, a large amount of depreciation expense might have to be recorded in the last year of the asset's life in order to make the final carrying value equal to its residual value. For example, suppose that the residual value of the equipment was expected to be only $2,000 (rather than $5,000). If this were the case, the depreciation schedule would be the same as shown in Exhibit 8-5 except that in 2015 the company would have to record $4,480 of depreciation expense in order to reduce the asset's carrying value from $6,480 at the end of 2014 to its assumed residual value of $2,000 at the end of 2015.

Recording Depreciation Expense

Regardless of the depreciation method, the recording of the expense is the same. The account Depreciation Expense is debited and Accumulated Depreciation is credited. The credit side of the entry is made to an accumulated depreciation account, not to the asset account. The accumulated depreciation account is a contra asset account that is used to accumulate the total amount of depreciation expense that has been recorded for the capital asset over its lifetime. The asset account shows the asset's acquisition cost, and the accumulated depreciation account shows how much of the cost has already been expensed. To give statement users more information, the accumulated depreciation account is used as an offset to the asset account, instead of reducing the asset directly. If users can see what the original cost was, they may be able to estimate how much the company will have to pay to replace the asset. Also, when the accumulated depreciation is offset against the asset, users can determine how much of the asset has been depreciated and can make a judgement about how soon the asset will need to be replaced.

EXHIBIT 8-5 DOUBLE-DECLINING-BALANCE METHOD OF DEPRECIATION

Capital assets are rarely acquired on the first day of a fiscal year. Most assets are acquired partway through the year, and companies have to then choose among the following accounting conventions for calculating depreciation. One convention is “the nearest whole month” rule. This convention calculates depreciation for the whole month if the asset was purchased in the first half of the month, because the asset was used for most of the month. If the asset was purchased in the last half of the month (the 15th of the month to the end), no depreciation is taken in that month, because the asset was used for less than half a month. A second convention is the “half year” rule. In this convention, half a year's depreciation is taken in the year the asset is acquired and in the year of disposal no matter when the asset was acquired or sold in the year. There are other conventions that can be used but knowing these two is sufficient for now.

In financial statements, companies normally show the total original costs of all tangible capital assets separately by category (such as land, buildings, and equipment) with accumulated depreciation for each category. Some companies show only one total for accumulated depreciation for all the various asset categories. Many companies show only the total net book value (cost less accumulated depreciation) in the statement of financial position, with the details provided in a note to the financial statements.

An example of detailed disclosures regarding property, plant, and equipment (sometimes called fixed assets) and related accumulated depreciation is shown in Exhibit 8-6. The information provided by Finning International Inc. related to its land, buildings, and equipment in its 2009 annual report is fairly typical of the type of supporting detail that is usually provided in notes accompanying the financial statements. Finning International is the largest Caterpillar dealer, selling, leasing, and servicing Carterpillar's heavy equipment in Canada.

In addition to recording regular depreciation expense, companies must periodically compare their assets' carrying values with the future benefits they expect to derive from their use. If the net book value, or carrying value, of an asset is higher than the future amount recoverable from the asset, it must be written down and a loss recorded to reflect the impairment in the asset's value. (Note that this is conceptually similar to the lower of cost and market valuation that is applied to inventories: the value recorded for an asset should not exceed its net realizable value, through use and/or sale.)

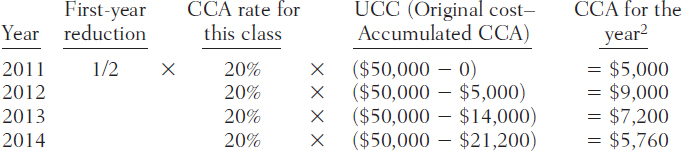

CORPORATE INCOME TAXES

The Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) does not allow companies to deduct depreciation expense when calculating their taxable income. However, it does allow a similar type of deduction, called capital cost allowance (CCA). In other words, although accountants deduct depreciation expense when they calculate net earnings on the statement of earnings, they have to use capital cost allowance instead of depreciation expense when they calculate the company's taxable income on its income tax return. CCA is calculated in a manner similar to accelerated depreciation, with several exceptions (described below).

EXHIBIT 8-6 FINNING INTERNATIONAL INC. 2009 ANNUAL REPORT

EXHIBIT 8-6 FINNING INTERNATIONAL INC. 2009 ANNUAL REPORT

Since the depreciation expense for accounting purposes and CCA for tax purposes are usually different amounts, the net carrying value of the capital assets in the company's accounting records will be different from the value in its tax records. For tax purposes, the net carrying value of capital assets is referred to as their undepreciated capital cost (UCC). So, while a company's accounting records will show the net book value (NBV) of its capital assets, its tax records will show a different value (the UCC) for these assets. To account for this difference, a deferred tax asset or liability results.

While it is not the purpose of this text to teach you about income taxes, which are subject to very complex rules, you should understand the basics of how capital cost allowance works. For tax purposes, capital assets are grouped into classes as defined by the Income Tax Act. For example, most vehicles are grouped into Class 10 and most equipment into Class 8. Each class has a prescribed rate that is used to calculate the maximum amount that may be deducted. For example, Class 10 has a rate of 30% and Class 8 has a 20% rate. In the year of acquisition, however, the maximum CCA that may be deducted for new assets is half of the normal amount.

Continuing with our previous example of a company that purchases equipment with a cost of $50,000 (and an estimated useful life of five years with a residual value of $5,000), and assuming that the equipment falls into Class 8 with a CCA rate of 20%, for tax purposes the company can deduct the following during the first four years.

Since the UCC is the equivalent of net book value for tax purposes, it declines each year by the amount of CCA claimed.3 You should also note that neither the estimated useful life of the asset nor its residual value are relevant for CCA calculations.

We have deliberately not shown 2015 in the table above, because what will be done for tax purposes in the final year of an asset's life depends on several factors that are beyond the scope of an introductory accounting text.

Assuming the company uses straight-line depreciation for accounting purposes, the annual depreciation expense is $9,000 per year (as shown in Exhibit 8-3). Exhibit 8-7 presents some additional data for the company and the calculation of income taxes for the first year of the asset's life, using an income tax rate of 40%.

It seems logical that the tax expense reported on the statement of earnings should be calculated based on the accounting earnings before tax that is reported on the statement of earnings, multiplied by the tax rate.4 In this example, the tax expense for the year will be $10,000 (as shown above). However, the amount owed to the CRA will be based on the taxable income reported on the company's income tax return. In this example, the tax payable for the year will be $11,600 (as shown above). The difference between these two amounts is recorded as a deferred income tax asset of $1,600. The journal entry to record the company's taxes is as follows:

EXHIBIT 8-7 DEFERRED INCOME TAX CALCULATIONS

As you can see in the preceding entry, the debit to tax expense is less than the credit to the tax payable account. To make the entry balance, we therefore have to debit the difference to a deferred income tax account.

As shown in the lower portion of Exhibit 8-7, the $1,600 difference between the amount of income tax expense for the period and the amount of income tax that has to be paid currently reflects the difference between the carrying values of the capital assets for accounting purposes (NBV of $41,000) and tax purposes (UCC of $45,000), multiplied by the tax rate. Whenever the carrying value of the capital assets for tax purposes is larger than their carrying value for accounting purposes, less tax will be paid in the future because the larger amount remaining for tax purposes will result in larger tax deductions in the future. The deferred income tax amount is therefore recorded as an asset, because it represents a benefit in the form of future income tax reductions.

The deferred income tax account will have a credit balance and be called a deferred income tax liability whenever the carrying value of the capital assets for tax purposes (their UCC) is smaller than their carrying value for accounting purposes (their NBV). When this occurs, more tax will have to be paid in the future, because the smaller UCC will result in smaller future CCA deductions. Thus, a deferred income tax liability represents tax that will have to be paid by the company later in the life of the capital assets, when the CCA deductions for tax purposes will be lower.

In summary, these deferred income tax balances arise from differences between the carrying value of capital assets for tax purposes (i.e., their undepreciated capital cost) compared with their carrying value for accounting purposes (i.e., their net book value). The discussion of income taxes is continued in Chapter 9.

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 4

Identify the factors that influence the choice of depreciation method.

CHOICE OF DEPRECIATION METHOD

Companies are free to use any of the depreciation methods that have been discussed, or other systematic and rational methods that suit their circumstances. The majority of companies use the straight-line method, probably because of its simplicity.

For practical reasons, because CCA is required for income tax purposes, many smaller companies choose to use it for their accounting depreciation as well. By doing so, they only have to do one set of calculations, and their record keeping and tax reporting are simplified.

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 5

Describe and implement changes in depreciation estimates and methods.

CHANGES IN DEPRECIATION ESTIMATES AND METHODS

Because the expected useful life and residual value are estimates, the assumptions used in their estimation may change over time. Companies must periodically revisit these estimates to ensure that they are still valid. For example, after an asset has been in service for several years, the company may change its estimate about the asset's remaining useful life. The asset may last longer or deteriorate faster than originally anticipated. Like all accounting estimate changes, a change in an estimate that is used to calculate depreciation is handled prospectively (in current and future periods). Note that there is no restatement of prior periods when an estimate is changed.

To illustrate how a change in depreciation assumptions is handled, the depreciation example in Exhibit 8-3 will be used. Assume that after the asset has been depreciated for three years the company decides that it has three more years of useful life left (i.e., it is now expected to have a useful life of six rather than five years), and its residual value at the end of the 2016 is expected to be $2,000. Based on these new assumptions, the company will recalculate its depreciation for years 2014, 2015, and 2016. The new calculation is based on the remaining net book value of $23,000 at the end of 2013, as shown in Exhibit 8-3. The revised depreciation schedule will be as shown in Exhibit 8-8.

The disclosure of changes in estimates in financial statements usually describes the nature of the change and the effects on the current year, if they are material. Companies are not required to make this type of disclosure, but voluntary disclosure improves the usefulness of the financial information.

Depreciation amounts can also change when new costs are added to the asset account as a result of major repairs or improvements to the asset. These generally will require new estimates of the asset's useful life and/or residual value, and are handled in the same way as changes in accounting estimates are.

During an asset's life, a company may also decide that a different depreciation method would more appropriately match the depreciation expense with the benefits received from the asset. If the decision to change to a different depreciation method is made as a result of changed circumstances, experience, or new information, the change is treated in the same way as changes in estimates are. The new depreciation method is applied to the asset's carrying value at the time that the change is made, and the company uses the new method over the asset's remaining useful life. If, however, the company determines that the change in depreciation method will provide more reliable and relevant information, the change must be recognized retrospectively by restating prior years' financial statements to incorporate the new depreciation method.

EXHIBIT 8-8 EXAMPLE OF CHANGES IN ESTIMATES OF USEFUL LIFE AND RESIDUAL VALUE

EARNINGS MANAGEMENT

The decisions about the estimates of useful life and residual value provide opportunities for management to make decisions that affect the net earnings amount on the statement of earnings. The choice of the depreciation method (straight line, declining balance) also provides an opportunity for management to impact the net earnings amount. The IFRS requirement for the choice of depreciation method provides a fair amount of latitude for management.

ADDITIONAL EXPENDITURES ON CAPITAL ASSETS DURING THEIR LIVES

It was mentioned above that new costs may be added to an asset account during the asset's life for major repairs and improvements. Typically, there will also be expenditures for maintenance and minor repairs throughout an asset's life. We must therefore consider how we should account for these types of costs. Should they be capitalized, as part of the asset's cost, or charged directly to expense? If these costs are capitalized, they will be charged to expense over several periods, in the form of depreciation. On the other hand, if they are expensed, they will go directly onto the current period's statement of earnings.

The general guideline to be followed here is that non-routine costs (such as those for major repairs and improvements) are usually capitalized, while the costs of routine items (such as maintenance and minor repairs) are expensed. The former types of costs are likely to increase the future benefits to be received from the asset (by extending its useful life, lowering its operating costs, or increasing its productivity). Therefore, in terms of the matching principle, it makes sense to capitalize these expenditures and then depreciate them over the periods that benefit from them.

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 6

Account for the disposal and writedown (impairment) of capital assets.

WRITEDOWNS AND DISPOSALS OF PROPERTY, PLANT, AND EQUIPMENT

Sometimes the future recoverable value of a capital asset (which reflects its ability to generate revenue and contribute to earnings in the future) declines below its carrying value. Some possible reasons for this decline are technological change, damage to the asset, or a change in the company's market. If the recoverable value of an asset is less than its net book value, the company must reduce (or write down) the asset's carrying value. This is accomplished by recognizing a loss on the statement of earnings and increasing the accumulated depreciation account by the amount of the loss. Increasing the accumulated depreciation decreases the net book value of the asset.

For example, suppose that at the end of the 2013, when the book value of the asset in Exhibit 8-3 is $23,000, the company determines that as a result of damage to the equipment the recoverable amount from its future use will be only $20,000. The following entry would be made to record the required writedown:

![]()

In all likelihood, subsequent to this decline in value the company would review the asset's estimated useful life and residual value so that changes could be made to the depreciation in future periods, if necessary.

At the end of an asset's useful life, the company usually disposes of it and replaces it with another asset, especially if the line of business is growing and prospering. In lines of business that are declining or being discontinued, old assets are not replaced and may even be sold or written off before they reach the end of their useful lives.

Normally, at the end of an asset's life, it is sold. If the company has accurately projected the residual value, there will be no gain or loss on the sale of the asset. However, if the residual value was not estimated accurately, either a gain or loss will result from this transaction. For example, suppose that the asset in Exhibit 8-3 is sold at the end of its useful life for $6,000. (Recall that its original cost was $50,000 and that its residual value was expected to be $5,000.) The following entry would be made to record its sale:

In this entry, the total depreciation recorded during the asset's life is removed from the accumulated depreciation account, at the same time as the original cost is removed from the equipment account. Note that the net of these two amounts is the asset's carrying or net book value at the time of sale, $5,000 ($50,000 − 45,000). Note also that you cannot simply credit the equipment account for the net amount of $5,000, as that would leave $45,000 in the asset account and $45,000 in the accumulated depreciation account when the asset is no longer owned by the company.

If the asset had been worthless at the end of its useful life, the asset's disposal would be recorded as above, except that no cash would be received. If we assume that no cash is received, then the write-off of the asset in our example would result in the following entry:

Note that, since the asset is worthless, the remaining net book value of $5,000 is written off and recorded as a loss on disposal.

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 7

Describe and implement the depreciation method used most frequently for natural resources.

NATURAL RESOURCES

Companies that deal with natural resources face some unique problems not associated with investments in property, plant, and equipment. For example, consider the situation of oil exploration companies, which incur large costs in their attempts to find oil. Some explorations are successful in finding oil and others are not. Should the costs of unsuccessful exploration be capitalized on the statement of financial position as assets, or should they be written off directly as expenses? If these costs are capitalized as assets, this implies that they have future value. But do they? And if the costs are capitalized, how should they be expensed? That is, what is the useful life of the asset being created, and what is a reasonable pattern of depreciation expense allocation over the useful life?

At the time of writing of this textbook, under IFRS there did not yet exist a standard for the oil and gas industry. Instead, companies were encouraged to continue to use accounting methods that had been used in the past as long as they continued to provide relevant information. In Canada, such companies have a choice of two methods to account for exploration costs: the full cost method and the successful efforts method. The full cost method capitalizes the costs of all explorations, both successful and unsuccessful, as long as the expected revenues from all the explorations are estimated to exceed the total costs. (The logic behind capitalizing the costs of unsuccessful exploration efforts is that, even though these attempts were not successful, they are necessary costs of finding oil and will produce future benefits because they will lead to successful attempts.) The successful efforts method, on the other hand, capitalizes only the cost of successful explorations and expenses any unsuccessful exploration costs. Sufficient time is allowed to determine whether an effort is or is not successful.

Generally, smaller oil companies use the full cost method, because using the successful efforts method would make their earnings appear to be very uneven from one accounting period to another, depending on the results of the wells they drilled during that particular period. Larger oil companies drill more wells every period, so they tend to use the successful efforts method because it is simpler to apply and its use over a large base does not produce uneven results from period to period.

Exhibit 8-9 includes examples from two companies.

EXHIBIT 8-9 ACCOUNTING FOR EXPLORATION AND DEVELOPMENT COSTS—FULL COST AND SUCCESSFUL EFFORTS METHODS

ACCOUNTING FOR EXPLORATION AND DEVELOPMENT COSTS—FULL COST AND SUCCESSFUL EFFORTS METHODS

Note that Alberta Oilsands Inc., an exploration and development company involved in the petroleum and natural gas industry in the Athabasca region of Alberta, uses the full cost method. It capitalizes the costs of drilling both productive and unproductive wells. In contrast, Suncor Energy Inc., a company involved in oil development in the tar sands of northern Alberta, uses the successful efforts method for its acquisition costs and exploratory drilling costs. Exploratory drilling costs of wells without proven reserves are expensed. Under the full cost method, all exploration costs are first capitalized and then expensed, through depreciation, over the life of the producing wells. Consequently, initial expenses are lower and subsequent depreciation charges are higher. Under the successful efforts method, only the costs associated with successful sites are capitalized and later depreciated over the period of production. Consequently, initial expenses are higher as the costs of the unsuccessful wells are expensed and subsequent depreciation charges are lower.

The depreciation of natural resources is often referred to as depletion. The depreciation method most commonly used is the units-of-activity or production method. For example, in the case of an oil field, the total number of barrels of oil expected to be produced from the field would be estimated. The depreciation expense would then be calculated by dividing the capitalized costs by the estimated total number of barrels to be produced from the field, to get a depreciation rate per barrel. This would then be multiplied by the number of barrels extracted each period.

For example, assume that a company estimates a field to contain 2 million barrels of oil. During an accounting period, 500,000 barrels of oil are extracted from the field. If the capitalized costs related to the oil field are $6 million, then the depletion expense recorded for the period would be $1.5 million.

$6,000,000 ÷ 2,000,000 barrels = $3 per barrel $3 per barrel × 500,000 barrels = $1,500,000

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 8

Explain the accounting difficulties associated with intangible assets.

INTANGIBLE ASSETS

As discussed earlier in the chapter, some assets can have probable future value to the company but not have any physical form. The knowledge gained from research and development or the customer awareness and loyalty produced by a well-run promotional campaign are examples of possible intangible assets. The companies that engage in these activities certainly hope that they will benefit from having spent money on them. However, the difficulty of determining the costs of producing intangible assets such as research and development knowledge or customer awareness and loyalty, and of quantifying the benefits that will be derived from them, make intangible assets a troublesome area for accountants. Although accountants would generally agree that these might constitute assets, the inability to provide reliable data concerning their costs and future benefits makes it hard to record these items objectively in the company's accounting system.

The capitalization guideline for intangible assets is that, if they are developed internally, the costs of developing them are expensed as incurred and no asset values are recorded. If intangible assets are purchased from independent entities, however, they can be capitalized at their acquisition costs.

An exception to this general guideline occurs with the development costs for a product or process. If certain conditions are met, these development costs may be capitalized and depreciated over the product's useful life. However, the basic research costs that occurred prior to any decision to develop the product or process are still expensed. The conditions for capitalization stipulate that the product or process must be clearly definable, technical feasibility must be established, management must intend to market the product in a defined market, and the company must have the resources needed to complete the project. These requirements are intended to ensure that development costs will be capitalized only if the product or process is actually marketable and will therefore produce future benefits in the form of revenues.

INTERNATIONAL PERSPECTIVES

In the United States, both research and development costs are expensed, and the related cash flows are classified as operating activities. This can result in large income differences, as well as differences in cash flows from operations, between a Canadian company and an American one.

The depreciation of an intangible asset is often referred to as amortization. Depreciating the cost of an intangible asset is similar to depreciating other capital assets. The company must estimate the asset's useful life and residual value (if any). Because of the estimation problems associated with intangible assets, this is sometimes very difficult to do. Typically, the method to depreciate intangibles is the straight-line method, with a residual value of zero. The useful life depends on the type of intangible asset. The one aspect of depreciation that is different for intangibles is that the accumulated depreciation account is rarely used. Most companies reduce their intangible assets directly, when they depreciate them. Because of the uncertain valuation of intangibles and the fact that these assets normally cannot be replaced, it is not as important for users to know what the original costs were. For example, the journal entry to record the depreciation of a patent would probably be as follows:

![]()

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 9

Depreciate intangible assets, where appropriate.

When estimating the useful life of an intangible asset, both the economic life and the legal life should be considered. Many intangible assets (such as patents and copyrights) have very well-defined legal lives, but may have less well-defined and shorter economic lives. Any intangible asset that has a definite life should be depreciated over its economic life or its legal life, whichever is shorter.

Note, however, that some intangible assets (such as trademarks and goodwill) have indefinite lives. Intangible assets with indefinite lives should not be depreciated in the usual manner. Instead, each of these assets must be evaluated each year to determine whether there has been any impairment in its value. If there has, the asset should be written down. If there has not, the asset will remain at its current carrying amount until the following year, when it will be evaluated again.

Several types of intangible assets pose special problems. These are discussed in the following sections.

accounting in the news

Biotechnology Intangibles

Small biotech companies are often founded on the strength of intangible assets in the form of scientific patents that hold potential for drug discoveries. The costs associated with developing new drugs, however, are extremely high, and pharmaceutical companies can spend a lot of money with no guarantee of their drugs ever reaching the marketplace. In fact, an Ernst & Young LLP report indicated that, during 2009, the gap between the financing for emerging companies and the larger, more established companies continued to widen. This is despite the fact that 2009 was an exceptional year for biotechnology companies in that the established biotech centres reached profitability for the first time in history. Although revenues fell, cost cutting, efficiency, and new creative models for funding and partnering enabled aggregate profits. Established Canadian biotechs increased the amount of capital raised.

The report, Beyond Borders: Global Biotechnology Report 2010, also stated that some research and development funding was directed to projects with potentially faster returns.

Source: Ernst & Young LLP, Beyond Borders: Global Biotechnology Report 2010, April 28, 2010.

Advertising

Companies spend enormous amounts of money advertising their products to increase current and future sales. Do expenditures on advertising create an asset for the company? If the advertising is successful, then the answer is probably yes. But how can the company know whether the advertising will be successful and what time periods will receive the benefits? If customers buy the company's products, it may be due to the advertising; but it may also be because they just happened to be in the store and saw them on the shelf, or because their neighbours have one, or because of many other factors. The intent of advertising is clearly to generate future benefits, which would usually lead to recording an asset; but determining the existence of the future benefits and measuring their value can be extremely difficult. These measurement uncertainties are so severe that accountants generally expense all advertising costs in the period in which the advertising occurs. If a company does capitalize this type of cost, it has to provide very strong evidence to support the creation of an asset.

Many companies spend a lot on advertising related to sporting events such as the Olympic Games and the World Cup. In many of these cases, the money is spent not just on advertisements during the games but also on pre-game financial support to the athletes, who then wear clothing and use equipment with the sponsors' logos on it. As you can probably imagine, it is very difficult to know how much future benefit will be received from these expenditures, and over what period of time.

Patents, Trademarks, and Copyrights

Patents, trademarks, and copyrights are legal entitlements that give their owner rights to use protected information. If the protected information has economic value, then the agreements are considered assets. Of course, determining whether they have value or not, and estimating the period over which the rights will continue to have value, can be a difficult task. Each entitlement may have a legal life associated with it, which may differ from its economic life. For example, in Canada a patent has a legal life of 20 years, but this does not mean that it will have an economic life of 20 years. The patent on a computer chip, for example, may have a useful economic life of only a few years, as a result of technological innovation. On the other hand, trademarks like Coca-Cola® may have an indefinite life. Copyrights have a legal term of the life of the creator plus 50 years. As with any intangible asset, the legal life serves as a maximum in the determination of the asset's useful life for accounting purposes.

accounting in the news

Advertising for the World Cup

Corporate sponsorship helped make the World Cup a reality in South Africa in 2010 by helping to fund the event's organization. Sponsorships for the 2010 World Cup enabled companies to have exclusive advertising opportunities not open to non-sponsors. Hyundai Kai Motors spent the most money, closely followed by Adidas, Emirates Airline, Sony, Coca-Cola, and Visa International. Spectators to the games (in person and through broadcasts) saw these names flash around the football field during the games, giving the company names maximum exposure. Omnicom Media Group MENA, a global advertising company, saw the advertising spending of companies increase by $60 million during the four weeks of the games. As well, various television companies that purchased the broadcast rights for the games saw their advertising revenues increase dramatically.

Source: Anil Bhoyrul, “World Cup to Net 120% TV Ads Boost—Media Guru,” Arabian Business.Com, June 6, 2010, http://www.arabianbusiness.com/589832

A company usually records these types of intangible assets only if it buys them from another entity. The costs of internally developed patents, trademarks, and copyrights are generally expensed, although some easily identifiable costs (such as registration and legal costs associated with obtaining a patent, trademark, or copyright) may be capitalized. These costs are then usually depreciated on a straight-line basis over the asset's estimated useful life.

In some cases, significant costs are subsequently incurred to defend and enforce patents, trademarks, and copyrights. Any costs related to successfully defending or enforcing these rights can be capitalized.

Goodwill

The intangible asset called goodwill represents the above-average profits that a company can earn as a result of a number of factors. For example, exceptional management expertise, a desirable location, and excellent employee or customer relations could give one company an economic advantage over other companies in the same industry and enable it to earn above-average profits.

accounting in the news

Patent Protection

In Canada, companies reap the benefits of patent protection laws that give them exclusivity for 20 years before others can use the product or process that has been developed. Many companies seek to expand their patent protection rights by registering their patents in other countries. Monsanto, a large U.S. agrichemical corporation, has developed and patented many genetically modified products and has sought global patent protection for its products.

Monsanto owns a patent for a DNA sequence that provides herbicide resistance in soya beans. It has been unable to obtain patent protection in Argentina for the sequence, although it believes that 95 percent of the soya beans grown in Argentina contain the DNA sequence developed by Monsanto. A Dutch company, Cefetra, was sued by Monsanto for importing soy meal from Argentina that it uses for the production of animal feed. Unable to demand royalties from the farmers in Argentina, Monsanto hoped to be able to get some of the royalties from the purchaser of the soya products. In a landmark decision, the Dutch court ruled that Monsanto's patent rights apply only to live plants and not to the DNA material in the soy meal.

This decision could have a major impact on patent protected products.

Source: Andrew Turley, “DNA Must Do Its Job for Patent Protection,” RCS: Advancing the Chemical Sciences, July 8, 2010, http://www.rsc.org/chemistryworld/News/2010/July/08071001.asp

Companies incur costs to create these types of goodwill. Advertising campaigns, public service programs, charitable gifts, and employee training programs all require outlays that, to some extent, contribute to the development of goodwill. This type of goodwill is sometimes referred to as internally developed goodwill.

As with other intangible assets, the costs of internally developed goodwill are expensed as they are incurred. In practice, goodwill is recorded as an asset only when it is part of the purchase price paid to acquire another company. Goodwill is not an easily identifiable asset, but is represented by the amount paid by the acquiring company for various valuable but intangible characteristics of the acquired company (such as good location, good management, etc.). These characteristics, in effect, give the acquired company a value that exceeds its identifiable assets (its buildings, inventory, etc.).