To paraphrase the poet John Donne, no company is an island. Businesses rely on their customers, suppliers, shippers, and investors. Nonprofit organizations rely on funders, donors, constituents, and supporters. All of these groups are stakeholders in the organization's success. The easier it is to communicate with people in these external (but integral) parts of the organization, the more effective they can be in their relationships to it. To continue—just as in any online community—the communication must be perceived as mutually beneficial by both sides.

Donors want to know how their giving is being put to use. Supporters want to volunteer their advice or influence. Customers look to companies to support the products they sell. Some customers even want to be involved in the product design process. To win (and keep) their involvement, the company needs to understand how these stakeholders think, plan, and make their decisions. The company needs the insight that stakeholders can provide to help it make its decisions.

These vital communications can take place in several ways: The company can open channels and invite its customers to talk to it directly; the company can share what it knows with its stakeholders; and the company can help its stakeholders share what they know with each other. All of these actions can benefit the company by forging stronger relationships with customers and constituents. External conversations can take place in the context of business-to-customer (B2C) relationships and business-to-business (B2B) relationships.

In this chapter, we cover the why and how of conversing online with external groups. The technical means are now available for organizations to become better listeners to their constituents and to respond more promptly and informatively to them. For most organizations, there is ample room for improvement in both of these areas, and relevant to the subject of this book, there is great potential for using enriched external knowledge to drive twenty-first century organizations.

Just as internal conversations require a thirst for knowledge to initiate and sustain them, external conversations require a need for engagement, commonly recognized by the organization and the members of the external group. The relationship defined by that need is likely to be asymmetrical; the contact is more important to the organization than it is to its stakeholders. In a free and competitive market, the business will always need the customer more than the customer needs the business. For that reason, everything the company does in its online conversations with external stakeholders must be done to please the stakeholders. That begins with internal attitude and extends to the communication technology and design.

In this chapter, we provide a variety of best practice examples. We've included screen shots with many of them to illustrate the importance of clear presentation on the Web page as an incentive for external groups to engage. Organizations are looking for cost-effective ways to gain access to the vital tacit knowledge contained in the interests, experiences, and opinions of their Web-connected stakeholders. Online conversation is an effective route to that knowledge.

Through the Internet, organizations can open ongoing conversations with thousands of customers. They can, but why should they? The most compelling reason is that, if they don't and their competitors do, those crafty competitors will have some big advantages. They will be building closer relationships with a very communicative and influential segment of customers. They will be gaining loyalty and access to viral marketing channels. But more important, they will be learning from their customers, in a more engaged manner, about how to make their products and services even better. External conversations build more informative relationships with more customers.

There is still resistance in many organizations to opening "that can of worms," which is how some people describe public, uncontrolled conversation opportunities with customers. They see more potential for trouble than upside in a forum that puts powerful companies and their customers on equal footing. The examples in this chapter demonstrate how some companies conquered this fear and resistance and moved ahead to realize solid benefits.

Using the Internet to converse with customers is still a pretty innovative idea. It's new enough to still be questioned within companies, often because people fear the public criticism that could appear in those conversations. That mindset fails to appreciate the reality of today's networked world. That criticism is probably already happening somewhere on the Net, if not on the company's site. To not move forward and engage in those conversations is to remove the company from an increasingly important aisle of the marketplace.

Seth Godin is one of the pioneers of Web marketing. He is also author of Permission Marketing and Unleashing the Idea Virus, two of the more creative books about attracting customers through the Internet. In a column in Fast Company,[89] he takes the reader through an analysis of how criticism stifles innovation. It may apply to your company. We think it applies aptly to the innovation of online customer conversation.

Companies that are market leaders are often the most afraid of innovating. Godin cites the following examples:

The fall of many retail giants to Wal-Mart

The lag in producing organic, nonengineered food products by Kraft

The lack of much content on cable or on the Net from CBS

Microsoft is an example of a company that forges ahead with innovation in spite of almost constant, scathing public criticism, he points out.

The stakes get higher, he explains, when companies have been successful because they feel that they have more to lose—that all they have built might come crashing down if they take a risk and change something. The fear often lies within the top-level executives who might have been the original innovators in the company but have become conservative behind the success of their original ideas.

Godin believes the main sources of criticism are the people who staff the company. Companies, he writes, "are far more likely to hire people to do jobs, as opposed to hiring people who figure out how to change their jobs for the better." Those do job people are more likely to support the status quo that brought them there. Why rock the boat with new ideas that may affect your job status?

The result of these combined tendencies to stand pat are that when a new idea comes along, such as creating a forum where customers can talk to each other about the company and its products, that idea and its worst possible outcomes are compared to the status quo and its best possible outcomes. It's an unfair comparison, of course. To get approval for such an innovation, it must promise to be vastly superior to the current methods for relating with customers.

Opening an online dialogue with customers does involve some risk. Your company may do a poor job of designing the interface. It may drop the ball on responding promptly and candidly to questions posed in public forums. The forums may be poorly managed. But these negative possibilities must be compared with the new reality—that your company, if it's known at all, already is being talked about somewhere on the Net.

If you're not involved in that conversation on the Net, you've already lost control over your public relations. You don't get to respond to your critics. You don't get a chance to win the loyalty of skeptical customers. You don't learn from their experience, opinions, and viewpoints. Do you have to be everywhere on the Net, responding to everyone? No, and you don't have to try to be everywhere. There are plenty of more practical options.

The first wave of business presence on the Web was a very expensive and very visible experiment. Some people made a lot of money and more people lost a lot of money, but there was much to be learned in this first venture into such an interactive and public environment. One lesson was that the companies that took the best advantage of the Web's interactive properties to build relationships with customers stood the best chance of surviving the experimental stage. Two well-known survivors have included conversations among their customers as vital elements of their online presence and branding identities.

While most of the new pure play Internet companies were burning through their venture capital building name recognition, the established brick-and-mortar companies were learning and adapting. They were leveraging their brands and the loyalty of their customers as they tried to figure out their place in relationship to the Web and how to change their strategies to make the best use of it. Some sooner than others, they began to buy domain names, build home pages, and establish a presence on the Web. The smartest of them observed and learned from the waves of new companies as they spent gobs of money attempting to use the Web to provide better service to retail markets, selling everything from pet food to software to automobiles.

The lesson these observers learned is that customers and their loyalty can't be bought through advertising; they must be earned through service. Relationships grow out of trust, and a customer's relationship with a business grows largely out of the perception that the business is sincere in its efforts to please. If customers see steady improvement in the way they are treated (and spoken to) by the business, they are likely to remain customers. The Web provides a convenient way for many companies to speak to and listen to many customers.

It's not a very complex formula, yet so many first-wave companies failed to connect with their user-customers that the exceptions stand out. Companies that relied on advertising, for both revenue and for branding purposes, did not attract large enough loyal followings to make a profit. Companies that emphasized customer relations as essential to their business models tended to build loyal markets that carried them through as they trimmed expenses.

If you ask consumers today which dot coms have survived the great downfall of 2000-2001, most—even those who have never shopped on the Web—will probably include eBay (www.ebay.com) and Amazon.com. Those two companies stand out not only for their name recognition but because they have provided two of the most successful models for businesses relating with customers through the Web. We'll describe how they each use conversational techniques later in this chapter, but both of these companies illustrate a third lesson of the dot-com experiment: Act on what customers tell you and make it easy for them to reach you with their input.

Unlike the B2C models of eBay and Amazon.com, the early B2B models for the Web looked to eliminate inefficiencies in how companies dealt with suppliers, buyers, and partners. The idea of online business exchanges grew out of the recognition that old processes had become more and more inefficient over time; they had failed to adapt. Customer tastes were changing faster than new products could be designed, assembled, and provided. By the time products came to market, tastes had changed and competitors had altered the market. Companies found themselves stuck with large inventories; they had too little time to get competitive bids on supplies; competition was fierce to innovate faster and cut costs.

The relationship between businesses is different in quality and purpose from that between businesses and their customers. However, there is still a need for communication and trust that the software interfaces of most online exchanges do not support. Lessons have been learned here, too, in the wreckage of many first-wave ventures.

Exchanges were envisioned as open marketplaces on the Web where multiple buyers and sellers could find one another through a common interface and where the bidding, ordering, procurement, and shipping processes could be made more efficient to fit just-in-time manufacturing models. Parts could be bought more cheaply and quickly, inventories could be kept low, and shipping could be tracked more accurately; business, legal, and transactional standards could be followed. Exchanges were meant to be online shortcuts in the normal flow of business.

Companies such as Ariba (www.ariba.com) and Commerce One (www.commerceone.com) were among the first to provide specially designed software to build exchange sites. Features to optimize routine procedures were incrementally added to what were primarily procurement-focused platforms; these included credit checking, financing, real-time order fulfillment, and invoicing. Yet although their platforms supported what they referred to as collaboration and interaction, they did not provide interfaces for buyers and sellers to meet online and converse. Those communications were still left to email, the telephone, and fax, which for most people meant switching from one medium to another to complete a transaction and service a relationship.

Many business exchanges were formed to attract and serve both horizontal and vertical industries, and many of them failed. A research article about B2B exchanges[90] blames most of the failures on there being too many of them, with too little quality control over the performance of vendors who sold on them and a reluctance of many companies to change their practices to fit the exchange model. Because vendors joined exchanges but didn't follow through on orders placed through them, buyers stopped relying on them. It doesn't take many negative experiences to extinguish a willingness to try something new.

The exchange model, says the article, needs to be refined, and many analysts agree that, in time, online exchanges will be successful. The main caution voiced by some analysts is that powerful exchanges, by bringing about the consolidation of vertical markets, might violate antitrust laws. But the article goes on to say, "One of the potentially most interesting effects of exchanges is their impact on supplier relations, customer loyalty, and customer retention." Furthermore, "customer/supplier intimacy is increasingly critical to a company's ability to differentiate itself from the competition." Intimacy comes through better communication, and a well-designed online exchange should provide the means for that communication.

VerticalNet (www.verticalnet.com) was founded and designed to provide a software platform to build portals to serve any vertical marketplace. Besides tools for all of the processes involved in procurement and selling, its interface included features to support conversation and relationship building among participants. An editor would be hired to manage content for each vertical market place, and a message board was provided for use as a knowledge-sharing forum. VerticalNet almost got it right by providing a framework that could be used by many different markets, but its timing and execution haven't yet brought the success its founders had hoped for. It has upgraded its process-oriented features to include what it calls "Strategic Sourcing, Collaborative Planning and Order Management," but most of its clients have yet to make optimum use of the site's message boards.

In VerticalNet's portal for aerospace buyers and sellers, shown in Figure 9.1, the community forum appears to be a quiet place in spite of the good selection of resources. Note the few discussions and old dates of last responses. A perusal of other VerticalNet exchanges shows this lack of participation to be pretty typical. One possible reason for the slow adoption of VerticalNet's message board could be gleaned from a study done by IDC, discussed in Cahners-Interstat,[91]of the acceptance of knowledge management practices across many vertical industries.

Reprinted by permission 2002 Vert Tech LLC. All rights reserved.

In an industry survey of companies serving 13 specific vertical market segments plus a category for "other," it was found that 10 of the 14 groups named "nonsupportive culture" as one of the two top challenges to implementing KM. Participation in the parts of the business exchange that involve person-to-person learning, as opposed to those that lead to closing deals and simplifying supply chain management, may not be deemed culturally important.

The study also concluded, "KM customers want to establish best practices to retain expertise, particularly related to customer support." So it may be that a platform such as VerticalNet can overcome cultural resistance to using its discussion boards by providing forums where users of the vertical portal discuss best practices discovered in putting the business tools to use.

Like many Web-based ventures from the 1990s, VerticalNet was early for its market, and in attempting to serve dozens of vertical marketplaces with one service, it may have overreached. But its founders understood the importance of social interaction in establishing a trusted trading environment. Vertical marketplaces define communities of interest. Those communities gather at conferences and trading conventions all the time. The challenge is not in proving to them that conversation is a valuable part of doing business; it's in convincing them that conversation in the online business exchange will work for them.

As the research paper cited earlier indicates, providers of business exchange sites need to be more selective in providing access to the exchange. Vendors and buyers must be committed to responding to transactions and interaction once they are members. And users—the buyers and sellers—need to learn how to maximize the potential benefits of their membership by understanding how the exchange can make a positive difference in their bottom lines.

Many people regard eBay as a consumer's business exchange. In our description of eBay later in this chapter, we point out the importance of building a culture of trust and open interaction among traders and between traders and site management. Marketplaces have their own cultures that define the rules of transaction and sustain their activity. Until business exchanges attract enough traffic and begin establishing social networks, most companies will continue to rely on traditional means of dealing with buyers and sellers, communicating through phone, fax, and email.

Organizations are still getting accustomed to the new and continually evolving capabilities provided by the Internet, the Web interface, and other new technologies for communication. The people outside organizations, whose only options for connecting with them used to be letters and telephones, now have many new formats for airing their views, providing their feedback, and issuing their complaints.

Markets are conversations that can lead to insight on both sides. The buyer and seller learn about each other and, if they so choose, work toward win-win situations. Conversations build the relationships that companies must nurture to excel. Conversations can help organizations and stakeholders work their way toward win-win solutions.

By conversing with your customers online, you can tap into all of this and give them another reason to stay in the relationship: You care enough about what they think to make it easy for them to talk to you. Indeed, they are likely to refer their friends. Any organization whose stakeholders establish lasting, mutually beneficial relationships with it has gained a powerful asset.

Businesses (and increasingly nonprofit organizations) spend tons of money learning about their customers' preferences and habits. For years, they've spent it on marketing studies, surveys, and focus groups. They once believed that conducting such research through the Net would yield invalid results; the population would be skewed toward the demographic groups who were more likely to be online. But now the online population is far more representative of the population as a whole than it was then. Online market research has arrived and is here to stay.

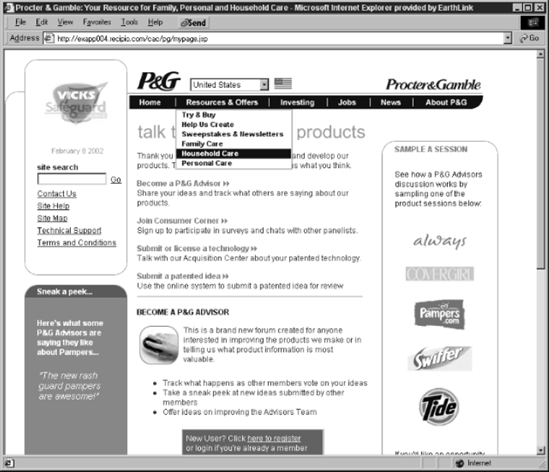

Recipio (www.recipio.com) provides what it describes as "the only Web-based customer relationship intelligence solution that allows leading companies to aggregate customer dialogue and turn the voice of their customers, employees and partners into a strategic asset." It may not be the "only" such solution, but in an article about the impact of online research,[92] John Ellis described how Procter & Gamble—"the biggest buyer of market-research services in the world"—uses Recipio's software to support online surveys and customer participation in discussion, advisory boards, focus groups, and collaborative product design.

Who knows how many people use Tide detergent or Ivory soap or who eat Pringles or brush their teeth with Crest or take Nyquil for a cold? P&G, it would be safe to say, has products in just about every American household and in tens of millions of households elsewhere in the world. With dozens of brand names to support, it's no wonder that it spends so much on market research. And it's no surprise that it figured out how to use the Web to reinforce and advance its market research.

Anyone can register at www.pg.com, where—in addition to tips and resources about family, household, and personal care—they invite visitors to "help us create." To that end, they provide a variety of formats for submitting feedback to, and for interacting with, Procter & Gamble. Once registered, a customer of P&G can, as Figure 9.2 shows, "talk to us about our products." Depending on the customer's preferences and available time, this can mean becoming an "advisor" or joining "Consumer Corner" where surveys are offered and one can be part of a customer panel. And beyond gathering advice and feedback from customers, P&G even offers to acquire new inventions or ideas for new products from visitors to its site. Given the high penetration of their products, as word gets around about such opportunities for customer involvement, odds are good that they'll attract a significant enough population to make the effort and the cost of Recipio's software and the staff to host the resulting communities of customers well worth the expense.

Hallmark, of greeting card fame, is another pioneer in using online conversation among customers as a strategic tool. To collect customer insights, Hallmark developed the Idea Exchange. In an interview provided for its software provider, Communispace,[93] Tom Brailsford, head of Hallmark's Knowledge Leadership Team, explains the genesis of Idea Exchange.

Brailsford had long been involved in consumer research and "the voice of the marketplace" and had observed how technology developed for doing surveys on the Internet. He wondered if there was a way to use technology to get closer to consumers and to change the interaction from the episodic process of repeatedly asking a question, then doing a study, and then getting an answer, to a more ongoing conversation with the marketplace.

Hallmark understood that consumers are a constituency that companies sell to but not a group that companies actively involve on an ongoing basis with product development or other internal knowledge-based processes. Hallmark decided to allow its customers to become involved, and it set up the consumer communities of Idea Exchange to use as an experimental research tool.

© Procter & Gamble

At first, Brailsford wanted to recruit volunteers to participate in this experiment and call them Honorary Hallmark Employees, but the company finally settled on calling them Consumer Consultants. Tom's group recruited the first 100 volunteers by contacting some people who had made purchases on the Hallmark Web site and calling some on the telephone. The volunteers were asked if they would like to participate—to answer questions and share their thoughts, feelings, and opinions about Hallmark products and ideas.

It was originally assumed that Hallmark would have to provide incentives for people to participate, and an elaborate incentive system was devised. They were surprised to find that people would have participated with no incentives at all because they were so happy—in fact, they were "starved"—to get the chance to have an active voice in a company they liked. The Idea Exchange is managed as a facilitated community. The facilitator, who helps guide discussion, is known to members of the community, and the members have become familiar with one another. The Exchange, as of the interview, had 200 members and would not be allowed to grow beyond that size in order to maintain that familiar atmosphere, but other communities were being planned.

Tom Brailsford is a member of the Conference Board Council on Knowledge Management and Learning Organizations and is a member of the advisory board of the "Mind of the Market Lab" at Harvard Business School. As he explains it, online consumer communities are appropriate for all companies because consumers these days feel a disenfranchisement from companies. He points out that consumers say they have a lot of information and ideas to contribute, and they emphasize to companies, "we're not dummies."

Brailsford believes that companies tend to see themselves in a sort of parent-child relationship with their customers, which does not motivate the customer to share knowledge with the company. Hallmark sees the relationship as more of a triangular system, consisting of feedback from the consumers to the company, news updates and information from the company to the consumers, and an ongoing relationship among the consumers themselves. This latter component has proven to be a big selling point in convincing consumers to participate and has resulted in participants telling their friends and family about the consumer communities. Now there are waiting lists of customers who want to sign up to be Consumer Consultants in Hallmark's expansion of new communities in the Idea Exchange.

The original impetus for setting up Hallmark's online consumer communities was a straightforward business goal: to increase revenue. The company had come to recognize ideas as the new capital of growth. Thus, the Idea Exchange was created to tap into a wealth of good ideas that Hallmark was convinced already existed in the marketplace, ideas for everything from new products to completely new businesses.

Originally, many of the Hallmark questions for the Consumer Consultants came from the editorial side of the company. The creative staff asked people what specific words they used to describe certain situations and also paid attention to the casual language used by the consumers in their informal conversations with one another. Today, Hallmark proactively explores themes with the community by asking them to brainstorm about certain questions: "What if we did this?" "What if we called it this?" "What idea or feeling would come up for you if we did this?"

In response to traditional marketing people objecting to this type of feedback as "statistically insignificantly valid," Brailsford responds that the Idea Exchange is not a substitute for quantitative tools but an adjunct to them. Unlike quantitative analyses, the Idea Exchange is not used for predictions but for insights and insight generation. Customer Consultants are asked for input on internal strategic business unit discussions and help with diagnoses. Tom considers their advice and input to be "way upstream" from quantitative research tools. In fact, the Idea Exchange members have even designed questionnaires, which Hallmark uses in more traditional consumer polling.

The results after the first 6 months of the project showed that the Consumer Consultants were more positive toward Hallmark. Those who had never bought Hallmark products bought some. Those who already had bought products bought more. They are grateful to Hallmark for giving them a voice and a way to contribute and are telling their friends about it. They are recruiting people for the next communities.

In sum, the Idea Exchange has proven to be not only a rich source for insight and idea generation but also an effective viral or social network-based marketing tool. Since Hallmark believes that communities need to be small to be actual communities, the plan is to open more communities of 200. The question then becomes: What if you want to have thousands of people involved in one large knowledge network? We begin with the basics of customer relations.

The field (let's call it an industry) of customer relationship management (CRM) has focused company attention on using network capabilities to learn more about customers. As one of the first special applications to branch off from knowledge management, CRM seeks to use all available information about customer behaviors and interaction with the company to build better profiles of typical and (especially) high-value customers. Using those profiles, the company can better predict customer behaviors and, by improving its customer service, increase high-value customer loyalty.

The continued rise in the use of the Internet is forcing advances in the technology and practice of CRM, and the cost to companies of new CRM technologies for gathering and analyzing customer data has been increasing steadily. A report by Cahners-Interstat projected increases in total worldwide CRM software application revenues from $9.4 billion in 2001 to approximately $30.6 billion in 2005. Yet many executives and experts are challenging the perception that technology is the real answer to the question of attracting and keeping customers. In fact, if the goal of CRM is to deliver better customer service, technology may be part of the problem by making customer service more complex.

Charles Fishman, in an article in Fast Company,[94] describes how Sprint PCS, the phone service, trains its customer service representatives for 6 weeks to provide support to people who are able to buy a phone and get on the service in 15 minutes. The increasing complexity of products and services available to nonexpert customers makes this support correspondingly more expensive to provide. Customer satisfaction numbers for services is declining across all industries. Whether support is delivered over the phone or through online interaction, companies often find themselves unable to please customers no matter how much they spend on call center technology, CRM applications, and training.

In 1993, Don Peppers and Martha Rogers published the first edition of The One to One Future: Building Relationships One Customer at a Time.[95] The title succinctly describes their approach, which was prescient because the Internet had not yet become the marketplace that would position the customer as a powerful and informed shopper. By surfing the Web, the customer now can study companies and decide, based on how the company represents itself online, which are most worthy of a relationship. This expanded capability to compare vendors has reinforced a consumer trend toward demanding more personalized service.

Personalized service means that the company, through its Web site, treats each customer differently based on past buying behaviors and expressed preferences. If you've bought products through Amazon.com, you know how it greets you on subsequent visits and presents you with products it thinks you might like based on your past purchases. Personalized service also can work through customer support call centers by allowing support representatives quickly to look up your transactions with the company and remedy problems efficiently.

Peppers and Rogers rode the wave of these marketplace realities and now manage a very influential consulting company (www.1to1.com) that emphasizes changes in strategy and process as well as in software. But although personalization of software interfaces is important in their approach, conversation is not emphasized as much as we believe it should be. Indeed, it's becoming more and more difficult to deliver custom service to one customer at a time. Leveraging technology to provide personalized service through company Web sites is one solution. Enabling online conversation that will distribute serviceoriented knowledge is another.

The Internet empowers consumers to make choices and to converse with each other about products, services, politics, and the marketplace. Word gets around fast in its constantly connected environment. When companies first began to get feedback through the Net from people who might never have taken the time to call their 800 numbers or write them letters, they took notice. They began to hear that customers and potential customers "out there" on the Web were exchanging opinions about their products and businesses. Customers were getting some one-to-one service, but it was from fellow customers, often sharing gripes and complaints. It was a public relations front companies hadn't recognized, and they have scrambled—with widely varying success—to deal with it.

As we mentioned in Chapter 2, "Using the Net to Share What People Know," some pioneering technology-based companies early in the Web's history provided places on their corporate sites for customers to connect with each other. Leaders of these companies figured that if customers were willing to communicate with each other (and with the company) within the relatively neutral environment of the Web, maybe there was less need to fabricate more contrived and less personal opportunities for customers to submit their opinions and preferences.

Market research, focus groups, and scientifically sampled surveys are, after all, contrived and truncated conversations, limited in what they can deliver in the way of customer insight. They don't convey detail and subtlety, and focus groups are known for eliciting views more representative of the participants' desire to please each other than of their true feelings. Plus, an online survey isn't likely to raise levels of customer loyalty.

But though the early practice of engaging customers in conversation worked for some companies, most others had (and still have) many questions about how to do it effectively and economically. Most still see CRM as the practice of identifying and aggregating all of the right numbers and statistics rather than one of establishing channels for trusted communication.

CRM, as understood by most companies, is not the same as customer relationship development. The Web provides technology to support relationship development through series communications with customers—what, in essence, are online conversations. Relationships now can be established and maintained that bring the design and marketing of products and services much closer to the people who will purchase and use them. Those relationships build trust and loyalty with Web-enabled buyers and donors. Relatively few companies, such as Hallmark, have realized the potential of putting online customer conversations to work, and their experiences serve as valuable lessons for doing business in a networked world.

Enterprise-level companies with huge populations of customers must be selective in opening their online conversations. That's why Hallmark limited its first Idea Exchange community to 200 members. But large businesses already have input streams of feedback, complaints, and queries from customers. Analysis of that input can help them decide which conversations, with which customers, will be most effective for them.

The same software provided on the Web site of Ask Jeeves (www.ask.com) is used internally by more than 65 companies, including Nike, Office Depot, and Dell. The companies pay an average of $250,000 per year to accept queries from customers and then generate daily, weekly, or monthly reports analyzing the questions and sorting them by content, date, time, and geography. The input received has been put to use by client companies to change and add new practices and products.

An article in Forbes magazine[96] describes how the online securities trading company Datek Online was motivated by input through its Ask Jeeves interface to add an options trading component to its site. And Daimler-Chrysler, responding to a stream of "how-to" queries about specific vehicle models, embraced the idea of "owner sites" that allowed owners of its vehicles to log on and get model-specific maintenance, warranty, and service information.

By providing a means through which customers can ask questions and make suggestions that can then be analyzed and sorted, a business can identify different categories of customers and needs, which in some cases can be addressed by appropriate online conversations. The closer the company can get to understanding the mentality of its customers, the better prepared it will be to opening online dialogue. If customers come to a company's site and find conversational opportunities that speak to their needs, they are much more likely to dive in and participate. The company will have shown that it has done its homework.

Knowledge networks form spontaneously on the Internet, just as they do on company intranets. Where there's a need for shared knowledge, there are now tools to support the communication and exchange. Consumers don't need the initiation or even the participation of a company to build an online community around the company's product or service. If the company is too slow to respond to this need, customers somewhere will begin a conversation on a message board or through email to find what they're looking for.

It's important for organizations to understand that people may be talking about them online and that those conversations could hold value. The knowledge shared among customers is richer than that owned by a single customer. A kind of informal collaboration happens when people talk about a product they all use, and the resulting shared insights often contain an elusive understanding that the company's product development and market research people would pay dearly to have. A discussion that takes place on a neutral site—not under the sponsorship of the company—is likely to be more candid and creative than a focus group or a discussion initiated by the company. We say "likely" because the example of Hallmark demonstrates that a company doesn't have to sacrifice the candor of its customers for control over the discussion space.

The rise of e-commerce exposed organizations to the new phenomenon of a Net-savvy marketplace. Consumers, on their own, gathered on publicly accessible community sites to discuss topics of common interest. Many of those discussions contained veins of pure marketing gold in conversations, observations, and opinions that would have been of interest to almost every business, cause, and profession that cared to know what its customers, constituents, and colleagues valued. Yet for years, public online discussions went unnoticed by businesses preoccupied with figuring out how to effectively market themselves through the Web environment. Those were the years of blind faith in banner ads.

Citizen-consumers found each other online to converse about health and medical frustrations; they swapped opinions about cars, fashion, music, technology, current events, and celebrities. They emailed each other links to recommended Web sites. A microbudget movie, The Blair Witch Project, rode a tsunami of brilliant guerilla-marketed Internet buzz to a record profit margin. Viral marketing enlisted interpersonal relationships to spread the word about notable products such as Napster, the peer-to-peer software that enabled millions of music fans to download from one another's PCs. Relationships built entirely through online conversation formed the bases of networked, interrelated online communities. Through the Web, people were telling each other what they liked, what they didn't like, and why. The Web has become the world's biggest ever word-of-mouth network, where keyboards rather than mouths spread the word.

Before the Web came to prominence, companies accepted surveys, focus groups, and polls as "good enough" means for assessing consumer preferences. But those measuring tools missed not only the passion and analysis that many consumers devote to products; they missed the reciprocal relationship that more conversational formats could provide. The nature of an ongoing conversation is to lead what might be a single idea and a single response into a deeper, more detailed interaction. A few intrepid companies and entrepreneurs recognized this kind of conversation happening in public chat rooms and message boards and decided to help facilitate it.

Pioneering companies, including those we mentioned earlier, found it quite natural to engage with their customers online because many of them shared the same skills and professions as the engineers or programmers who designed the company's products. So, as we describe later in the chapter, Sun Microsystems was one of the first examples of a business supporting a strategic online customer community. But people by the thousands already had begun engaging with each other around products of common interest in spontaneous communities not related to any specific companies.

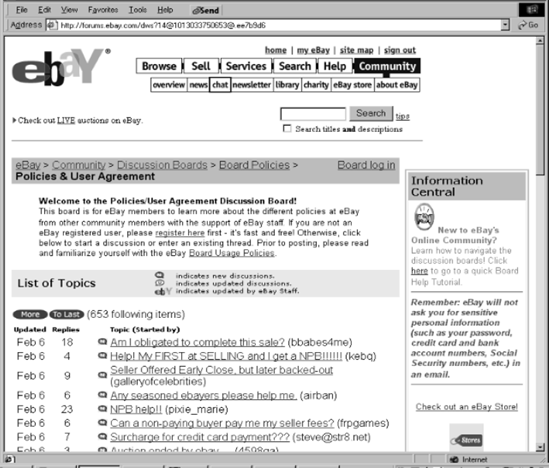

If any pure play Web business model stands as an example of perfect adaptation to the networked environment, it is eBay. Employing the Web's speed and ability to organize information and to support a product display and bidding process, it provides a virtual flea market interface, where anyone can register and sell goods for the highest offer. The main technological features of eBay are its categorized auction interface and the tools it provides for personalization and reporting the trustworthiness of participants in its marketplace. One personalization feature, illustrated in Figure 9.3, is the eBay member's My eBay page. The one pictured is of the author's personal page, showing how it keeps track of auction items of interest, items being bid on, and items on which the member has made winning bids. The tracking tools encourage involvement by active traders. The power of the individual member is enhanced by such features, but as its CEO, Meg Whitman testifies, the not-so-secret secret of eBay's success is in its support of community.

Community drives eBay's word-of-mouth marketing and its rapid adaptation to customer needs and preferences. It has built its reputation and its base of regular members through grass-roots selling and buying, and it's in the interest of members to attract new members and expand the marketplace in which they trade.

Many other auction sites, including Yahoo!Auctions, have been launched on the Web, and software platforms for supporting the auction model have been produced and sold, but eBay distinguished itself early in its history by deciding to steer many of its decisions based on the input of its members. Mary Lou Song was the third employee at eBay, and when she joined the company in 1996, it had 15,000 members; it now claims over 16 million. Song helped develop its young community, building the cooperative relationship between the community and the company through combining traditional product marketing—to attract the right people, with online community marketing to win their loyalty once they had joined. Her goal was, and still is, to make membership a fun and safe experience.

Reproduced with the permission of eBay Inc. © eBay Inc. All rights reserved.

For the designers of both the interface and the business process (a company spared of the obligations to handle merchandise or shipping), eBay was an ongoing learning experience based on conscientious customer listening. And for the community managers like Song, the community was a source of essential feedback and an audience that needed to be kept informed. Even policy questions— an area usually dealt with by companies in locations far beyond the reach of customers—have been brought into the public forum as shown in Figure 9.4.

Reproduced with the permission of eBay Inc. © eBay Inc. All rights reserved.

Through experience and attention, eBay has learned the following important lessons about including their members in decisions that affect their buying and selling activities:

Lesson 1: Make your policies clear and bring discussion of policies out into the open. Where customers depend on policies to put their trust in a business or social process, and where the company depends on customers for its success, it's smart to invite the customers into the policymaking discussion.

Lesson 2: Be proactive. Note the security reassurance about not asking for sensitive personal information in email.

Because of the open nature of its auction activity, eBay is frequently in the news for the items that some people attempt to sell—from bogus famous paintings to human organs. At one point, the company instituted a policy of not permitting the sale of firearms. It did this for its own ethical reasons but failed to include its members in the deliberative process before making the announcement. It learned from indignant customer reactions that, even in cases where its corporate mind was made up, it needs at least to confer with its member population before implementing a policy change.

The auctions on eBay also have been subject to occasional fraudulent behavior over the years such as sellers taking the money and not delivering the goods and buyers receiving the goods and not sending the money. At times, goods sold were not delivered as described. The software, in combination with the participation of members, has attempted to address these betrayals of trust by providing a means for members to assign other members a feedback rating based on the total of positive, negative, and neutral reviews of their transactions.

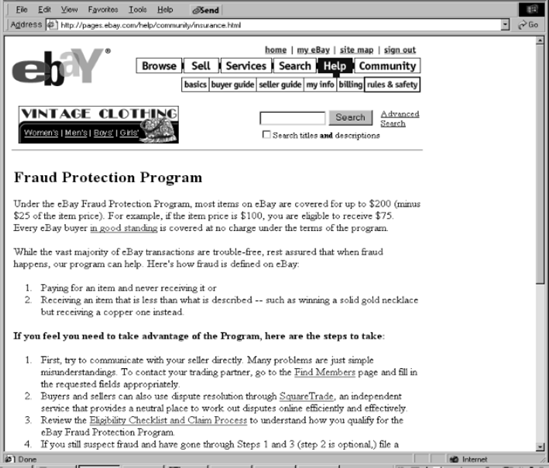

A prospective buyer will want to see the feedback profile of the person selling an item. The rating page will show the number of positive, negative, and neutral ratings given to the seller over the past 6 months and will display any comments written about the seller by people who have bought from him. Still, there is the possibility of fraud, as shills—associates of the seller or phony members created by the seller—might be providing the positive ratings. So eBay has devised more comprehensive fraud protection: insurance that will reimburse members a portion of the money they lose in a bad transaction (see Figure 9.5). Fraud had been perpetrated on eBay members on several very publicly visible occasions, so the company chose to address it head-on in discussions with members and in this policy.

Though eBay began as what would be considered a trading site, where individuals sold items to each other as if it were a virtual yard sale, it has adapted its technology and its culture to include retail sales, where companies offer goods for sale beginning at set prices. The trust-enhancing qualities of its community approach have been extended to cover small to large businesses, and many of the original individuals who once sold the occasional item now make their livings by selling through eBay. The culture has evolved, but the focus has continued to be on maintaining a trusted marketplace through encouraging conversation among members and between members and the eBay staff.

Reproduced with the permission of eBay Inc. © eBay Inc. All rights reserved..

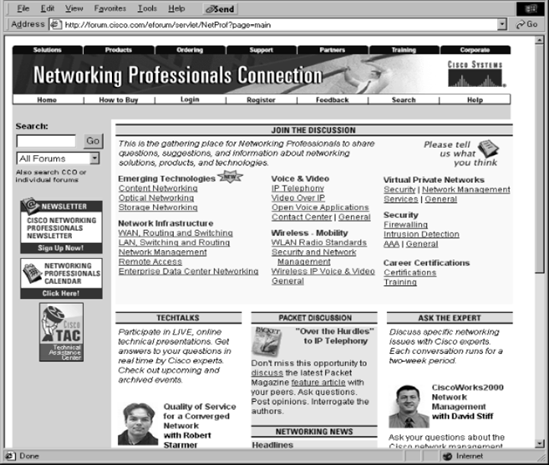

We've used Cisco's NetPro community as a case study in previous chapters. Here we use it as an example of a company creating a place on its Web site to attract a specific group that already has an established, unaffiliated meeting place. In Cisco's case, the group consists of the networking professionals that install, configure, and maintain the kind of technology Cisco provides.

As we've noted previously, technical communities were the first ones to form on computer-mediated networks. Technicians just happened to be the people designing and building the networks, so it's natural that they were the first ones to inhabit them. To this day, technical people naturally form online communities to share knowledge, mostly using email or the conventions of Usenet. One newsgroup, comp.dcom.vpn, is all about virtual private networking (VPN), the technology that allows employees to connect to the corporate intranet through a secure remote modem connection. In this newsgroup, networking professionals exchange knowledge about VPN, and it doesn't matter what company they work for.

Cisco produces and sells VPN technology and equipment for many other aspects of Internet and intranet functionality. The company wanted to attract the same professionals who were using comp.dcom.vpn and other online communities to discuss networking hardware. They had to offer incentives to get them to change their behavior; most workers don't have the time or social bandwidth to be members of more than one community addressing a single interest. Cisco's main appeal was its status as the largest producer of networking equipment in the world. Since some of that equipment was regarded as the global standard for Internet connectivity, the promise of learning more about Cisco equipment and having a closer relationship to Cisco was important, career-wise, to many of the targeted professionals.

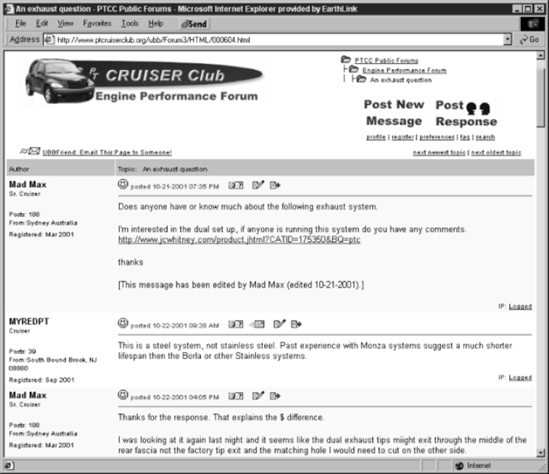

Similar situations can be found today among companies and professionals whose products and interest lie outside the technical realm. Users of products— cars, bikes, gardening equipment, stereo equipment—gather spontaneously on the Web, and the makers of the products they're talking about invite them to gather on their product support sites. If the conversation switches venue from the nonaffiliated message board to the company-sponsored message board, the context changes. The meeting place is no longer spontaneous and independent but is created, owned, managed, and maintained by the company.

A professional community, once it convenes on the company site, stands to lose some of its autonomy and ability to self-govern. The company, meanwhile, takes on a new obligation: to provide the meeting space while keeping the professionals happy with the trade-off they have made. Both the company and the professional community are seeking an arrangement of mutual benefit.

Cisco was cautious in its approach to the networking professionals. It first attempted to attract attention and stir interest by staging online events: slide presentations with live audio featuring product managers and engineers representing its VPN team. These experts answered questions from a moderator and from the online audience. Out of those events, Cisco identified professionals who registered and posed questions and then contacted them about becoming founding members of its planned discussion community.

As the initial online interface was designed and the back end of the system was assembled, the decision was made to begin the community with a narrow focus, VPN, but to be ready to expand into other technical topics likely to be of interest. IP telephony was one alternative and security was another. The system was launched with a small population that helped Cisco's community team iron out the bugs in the interface. As the design was tuned, more participants arrived and the community began to grow, driven by word of mouth. Cisco learned to manage the community to the satisfaction of its members.

Now the Networking Professionals Connection is a lively knowledge exchange where the professionals learn from one another and Cisco learns from their conversations. Members can choose from a variety of activities and information resources (see Figure 9.6) and are invited to submit input to Cisco about the community, its design, and its administration. The NetPro community, as it's called, began with one main topic: virtual private networking. As the community expresses its interest in other topics, the focus of the community is expanded. As Figure 9.6 shows, there are now topics on emerging technologies.

© Cisco Systems

Michael Ruettgers, president and CEO of EMC Corporation, a $4-billion provider of intelligent enterprise storage systems, software, and services, claims to be "relentless" in keeping up to date with what his customers want and value. The challenge, as he describes it in an article on the Chief Executive Web site,[97] is in implementing practices to learn from customers "consistently and methodically." In answer to that challenge, his company follows four principles, which he claims "not only look outward to our customers, but also bring customers into the heart of our product development process."

The first principle is that customer closeness should start in the boardroom. At EMC, the chairman and founder, even though retired from management activities, spends considerable time meeting with customers one-on-one and in "chairman's dinners." By getting customers—from the easy-to-please variety to the most demanding—to confide in him, he learns about what they really need and care about. His obsession with knowing the customer has rubbed off on upper management and the entire organization. The need to get closer with all of the company's customers has led to the development of IT systems and online means for finding out what they want.

The second principle is to create a customer trust loop, which involves "listening, responding, validating, refining, revalidating, delivering, fine-tuning— and then repeating the process. Only through constantly going through this loop will the organization know that its perspective of what the customer wants is, indeed, the customer's perspective. In our experiences managing online communities, we have kept this trust loop going continually, listening and then validating, acting on suggestions and then asking customers, "Is this what you meant?" Just as you would with your employees, you keep the communications channels open and respond promptly to input. Only by staying responsive and delivering on the suggestions you are hearing from customers can you win and maintain their trust and valuable feedback.

As eBay does, EMC invites customers that it identifies as highly motivated to come to its headquarters and meet intensively with EMC executives and managers, who listen to what they have to say and then go through the response-validation-refinement loop to make sure the customers' needs are truly understood. This is face-to-face stuff, where relationships are built that will remain strong when the communication reverts to virtual channels. A core of loyal customers who understand the sincerity and motivations of the company can be a strong influence on the majority of online customers, who may only know the company through conversation on the Net.

The third principle followed at EMC is to strike a balance between leading the customers and following their leads. As Ruettgers points out, it was not customer leadership that brought the invention of the electric light, the laser, intermittent wipers, and the minivan. The same could be said for the World Wide Web. Customers tend to ask for refinement and improvement in what they already have. They want things to be faster, cheaper, easier to use. But innovators within companies need the input of customers to know if the products they are developing are on the right track for usability, convenience, and design. Likewise, companies need to be able to collaborate with their suppliers in designing parts and components as new products are created.

Investing for customer activism is EMC's fourth principle. The investment is in terms of executive involvement, primarily, for the CEO can create a tone in the organization that is welcoming to customer input and fosters strong relationships between the company and its customers. The investment also includes making it as easy as possible for customers to provide input into the product design process. The company invests in quick turnaround of product improvements that are suggested by customers. And it invests in providing products that have been well thought-out concerning the customer's life cycle with their products, simplifying their purchase, use, and upgrading. EMC believes in reinforcing the innovative intelligence of its customers and investing to tap into that resource.

Observant pundits and analysts recognized the rise of spontaneous consumer communities as soon as they began forming on the Web. One of the first attempts to aggregate communities and content according to special interest was called The Mining Company. It provided a template for building focused Web sites and invited people with experience and expertise in a subject area to become a combination online community leader and editor, organizing the sites, linking to relevant information, providing original content, and managing online conversation. These so-called guides were paid a percentage of the company's advertising revenue, and the best sites became known as expert knowledge-sharing communities where users exchanged techniques and opinions about various products. The company later changed its name to About.com (www.about.com) and still stands as a good example of what user-driven portals can be.

Topic-focused communities on About.com cover hundreds of hobbies, interests, skills, and fields of knowledge. Included in the site's contents and discussions are thousands of products and services that serve these subject areas and attract people with varying amounts of expertise. A visit to the Fresh Water Aquarium community reveals product reviews and online discussions about different types of fish, tanks, water conditioning, and diseases. The experience represented by participants is much broader than could be found on any one product provider's site. But product review is not the main mission of About.com. Other Web sites have been created to specialize in that area.

In 1998, Consumer Review magazine brought its professional product testing and evaluation services online as ConsumerREVIEW.com. Through the Web, it began accepting input from paying subscribers to complement its own objective studies and ratings. In 1999, Epinions.com (see Figure 9.7) was launched to provide a specially designed gathering place for people to submit their own reviews and ratings of products and to research what others thought about those and other products or services. The Epinions interface allows every registered member to build a personal Web of Trust made up of credible reviewers and the people who also find them credible. Trust is important to offset any mis-leading ratings and reviews that might be posted by corporate shills—unidentified company reps posting good reviews of their own products.

© epinions

Consumers began using these review sites as important shopping guides, reporting the results to each other. Eventually, companies whose products were critiqued positively or negatively began to get wind of the feedback. Some began regularly monitoring Web sites where their products were being discussed. In the case of strictly ad-supported review sites, there is no guarantee of survival, but Epinions now earns revenue by generating leads for retailers to whom it provides links from its product review pages. ConsumerREVIEW.com, on the other hand, has two steady revenue sources: subscription fees for both their print magazine and their Web site. Together, this income supports its publishing activities and its product evaluation work.

In the difficulty encountered by companies searching for feedback about their products and services in the vastness of the Web, another business opportunity was recognized. New ventures were created to perform the searching and monitoring of the Web for companies hungry for knowledge of consumer thinking and journalistic mentions. Going by names such as Cyveillance, E-Watch, CyberAlert, WebClipping, or NetCurrent, they provided a kind of digital clipping service, sending their clients daily electronic reports of quoted conversations and mentions in the online press.

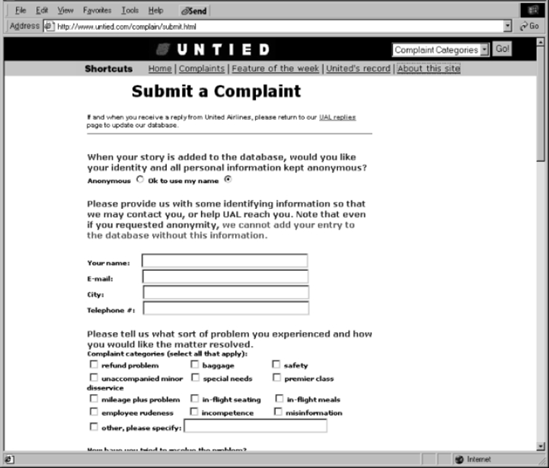

An online service called PlanetFeedback (see Figure 9.8) makes most of its revenue by providing these services. Its Web site also provides a single point of access for consumers to send complaints and suggestions to businesses. As the company's CEO, Pete Blackshaw, explained as financial justification for companies making use of its services, "If you totaled the money the Krafts, Unilevers, P&Gs and [Johnson & Johnsons] spend listening to consumers tell them how to improve a product, you're going to be in the hundreds of millions of dollars."[98] Subscribing businesses get to see the feedback but don't necessarily respond to any of it. And as we described earlier in the chapter, P&G has its own online methods for soliciting customer input.

PlanetFeedback recently merged with another technology firm called Intelliseek, which originally provided a service for dealing with two problems facing companies: the overabundance of information and the variable reliability, importance, and impact of that information on the company. Intelliseek not only found relevant information, but it filtered out the "noise" from the truly useful stuff. Now the merged service can deliver relevant and meaningful reports from online conversations and publications to its clients.

Services like PlanetFeedback are useful when there are active conversations happening on the Web about your company. But they don't provide you with a convenient opportunity to respond—to make amends for a customer's dissatisfaction, to assure customers that a problem has been corrected, or to invite the customer to describe how your company could improve itself. And with the collapse of the business models that have supported many of the public discussion sites, there's no guarantee that those useful conversations will continue to be available for harvesting by these special purpose search engines. Yet the value of that feedback is such that forward-looking companies must provide their own channels for it.

The online conversations among customers and those between customers and representatives of the company have many similarities to the online conversations among employees we described in Chapter 8, "Initiating and Supporting Internal Conversation." Trust among participants is necessary for most people to reveal what they know and think. Leadership is important in building that trust and in setting the focus for knowledge sharing. Facilitation is often useful to help people express themselves and to stimulate the social interaction. Site design and organization must be appropriate to the needs of the community not only to reduce barriers to participation but also to allow participants to find what they need with minimal hassle. But there are some significant differences, too, between communities composed of employees of an organization and those composed of external stakeholders.

An organization is limited to exerting less control over the content and direction of online conversations among customers or constituents. It can set no goals or deadlines or deliverables as it can for an internal project team. The policies it imposes cannot be too restrictive or people will refuse to participate. It must spend more of its time listening and helping participants explain what they are trying to tell the organization rather than keeping the conversation aligned with its strategy. The incentives it offers for participation must be stronger because there is no compensation structure or prestige attached to a customer's input to a business. The position of the company with respect to its customers is a supplicant asking humbly for contributions. Yet, if invited in the right way, many stakeholders will be excited by the opportunity to help make a company's products or services better.

The social aspects of initiating and supporting conversation across the fire-wall—between representatives of the organization and external groups—are trickier than they are on the intranet. There is less room for error in relationships between a business and its customers or between an organization and its constituents. In effect, they are the guests and the organization is the host to the interaction. The host is obliged to extend courtesy and to be tolerant of transgressions. With internal conversation, there is room for conflict, multilateral disagreement, debate, and even the occasional insult. Vigorous debate may, in fact, be encouraged. Try any of that with a customer and the ripples of bad PR will spread far and wide, with the speed of email.

Interface design is more important in supporting external relationships for the same reason: There is less room for mistakes like downtime and clumsy navigation. The company can't be constantly tweaking the interface when the users are guests; that would be considered inconsiderate at best and incompetent at worst. The interface must be designed with the convenience and needs of the customer or constituent in mind rather than the needs of the internal groups doing the listening and outreach. Staff members don't quit their jobs because the discussion board is tricky to use, but customers will abandon a Web site that forces them to go through a tricky learning process.

You can invite people to give you feedback and help you to satisfy them, but there are costs and preparations associated with acquiring their deep input and ongoing collaboration:

People who provide your company with valuable input will expect some valuable takeaways in return. You must know what those expectations are.

People expect you to provide an intuitive and comfortable interface for their participation and input.

Appropriate and timely content combined with a prompt, courteous response from staff will keep people coming back.

With a wise investment of time, research, and training, combined with good execution, a company can turn the initial trickle of curious and hopeful participants into a population of loyal and regular collaborators. Building the relationships that anchor that loyalty takes commitment and purpose.

The Wharton School not only studies businesses; as a prestigious academic institution, it is itself a business. In an article on its Web site[99] (knowledge.whar-ton.upenn.edu), it describes how companies learn from online customer dialogue and how it uses message boards as a recruiting tool.

One of the school's marketing professors says, "even if negative comments come up in the online discussions, companies seem willing to live with that for what they feel is a positive overall experience of talking about products and services." (That occurs if they overcome the initial internal resistance to the idea.) Another marketing professor is not so optimistic, venturing the opinion that online word-of-mouth is nothing special. Of course, that's not to say that online interaction doesn't work; it just may not be more effective than offline talk. We'll grant that, except that companies can talk to far fewer people offline.

The Wharton School itself provides message boards for students and prospective students. Alex Brown, associate director of MBA admissions, says these have proven to be a great way to help market the school and its programs. MBA candidates are no longer captive of dialogue controlled by the business schools and their admissions departments. Candidates, he says, "are talking to each other about what we offer and how it compares to other schools."

After setting up their discussion boards, Wharton wondered if it should "take the next step and host those discussions or ignore them." They decided to participate in them and embrace them "rather than let the rumor mill take over." Students and prospective students interact and answer questions for one another. Those who are looking for a place to continue their studies get a taste of the culture of the student body and staff. They get beyond the surface promotion of brochures and the superficial physical impressions of buildings and classrooms.

The debate between the professor who favors organizations hosting online dialogue with stakeholders and the professor who is skeptical of the value of such dialogue revolves around the trustworthiness of the input. As the skeptic expressed his doubts, "I would hesitate to draw any conclusions about chat on a company-based Web site. Those are squeaky wheels seeking grease on those sites. And who knows if the company is monitoring the discussion or steering it in a direction that the company desires?" Of course, when done right, the company fosters candid relationships and is monitoring discussions and responding truthfully when appropriate. The squeaky wheels may not represent all customers, but they do represent a motivated portion of them. And motivated customers provide especially valuable input.

In Chapter 2, we described the early users groups of Apple computers and how they exchanged rare information first in face-to-face meetings and then through computer BBSs. Technical populations, enthusiastic about using technology to communicate, led the way in giving advice to each other and to product vendors about innovation and improvement.

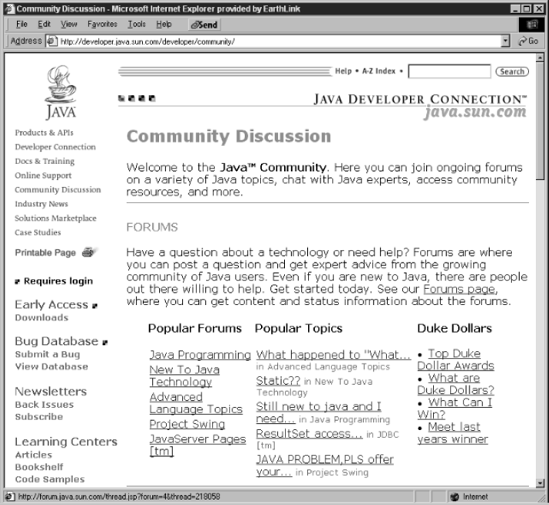

Sun Microsystems (www.sun.com) has long relied on the ability of programmers and computer engineers to communicate through the Net. It was one of the first companies to provide space on a Web site for users of its products to converse with one another. Today, it continues to host a variety of what it calls "developers forums" for discussion of different products and their applications. These range from communities for system administrators of Sun-powered installations to software developers using Sun technologies like Java and Jini. Figure 9.9 shows the Java Developer Connection, a kind of peer-to-peer knowledge exchange similar in purpose to Cisco's Networking Professionals community.

As Sun describes another of their forums, "Dot-Com Builder Discussion Forums are an interactive area where Sun's Web developer community can share knowledge by posting messages to a message board. Messages on the message board are organized by topic, cover all aspects of server-side architecture and Web development, and include community member comments, opinions, questions, answers, and technical tips." Of course, Sun also benefits greatly by having access to the creative conversations that go on among experts in using its products.

For one of its software technologies, Sun has provided a community site away from its home site. Jini allows dissimilar processes and devices to communicate and work together. Its potential uses are so numerous that Sun initiated a special development community, complete with a constitution, for sharing new solutions. The community (at www.jini.org) was begun with several high-level Sun engineers serving as facilitators. The goal was to make the community self-governing, and to that end, a community constitution was composed by its members to state the agreed-upon procedures for sharing solutions and setting standards. The participants in the Jini community preferred to stick with email as their platform for interaction. They were comfortable with it, and combined with the ability to create Web pages that could be shared with other members, it was the most appropriate technology for their collaborative needs.

Figure 9.9. Sun Microsystems' Java software language has relied on collaborative innovation by its users.

©Sun Microsystems

Only a cohesive group with a goal of mutual benefit can reach this level of agreement. However, there are many products that would lend themselves to such an arrangement if only the companies that produce them would recognize the potential. Clearly, the more solutions that are devised by the Jini community for applying the technology, the more Sun has to gain.

At one time, online community was envisioned as an ad-supported revenue center. When this failed to pan out, the focus shifted to view online community as part of customer relations—a cost of doing business like marketing and PR. But some companies see it as a cost-cutting activity, replacing some of the expense of customer support. If done well, customers not only provide each other with advice that the company was once liable for, but customers provide better advice because it is experientially based and the customers are professionals.

Click on the Technical Support link on Hewlett-Packard's home page (www.hp.com) and then on the link to Forums for IT Professionals and Businesses. You reach the IT Resource Center (ITRC), a Web page that leads you to what HP identifies as its four main categories of customers: IT professionals, business professionals, developers and solutions partners, and home and home office customers. And as HP states on this page, "Different forums may have different rules and guidelines."

It's significant that home and home office customers aren't provided with actual discussion forums in ITRC, whereas the other groups are. Managing a discussion community composed of tens of thousands of owners of hundreds of models of HP PCs and printers would be a daunting and expensive task. All of the customer communities get indexed troubleshooting menus, search tools for solutions, and company support provided through email. The forums aimed at professionals in the other three support areas do encourage interaction and knowledge exchange.

HP recognizes the potential bottom line benefits of users helping other users to the extent that it set up a points system to recognize users who answer a lot of questions. The leaders in accumulating points are recognized on the forum's home page and by symbols displayed by their posts in the discussion space. By accumulating points as valued knowledge resources, they can rise in rank from Pro (symbolized by a baseball cap icon) to Graduate (a mortarboard icon) to Wizard (magician's hat) to ITRC Royalty (a crown). HP claims that it may (but is not obligated to) award gifts to such participants.

In its terms of use, HP describes, in part, its relationship to the Communications—the content of user discussion in its forums. The terms say, "HP may, but is not obligated to, monitor or review any areas on the Site where users transmit or post Communications or communicate solely with each other." This relieves it of responsibility for inaccurate or offensive posts written by users, but it's very likely that Communications containing information of value to HP will be noticed and made use of. Indeed, as on most corporate sites, the company claims the right to make use of whatever information its users post. "HP and its designees will be free to copy, disclose, distribute, incorporate and otherwise use the Communications and all data, images, sounds, text, and other things ..." in any way it chooses.

One of the Web's most effective uses is as a reference resource for people with questions about health and medicine. With the rising cost of health care, people are using the Web to research their own conditions and treatments. The more serious the health problem, the more vital the information. The motivation to collaborate with others around different conditions is very high compared to almost any other topic, whether business-related or personal. The trick is in providing reliable information and managing helpful online conversation.

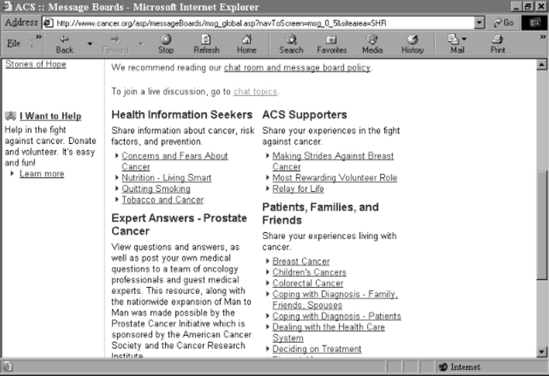

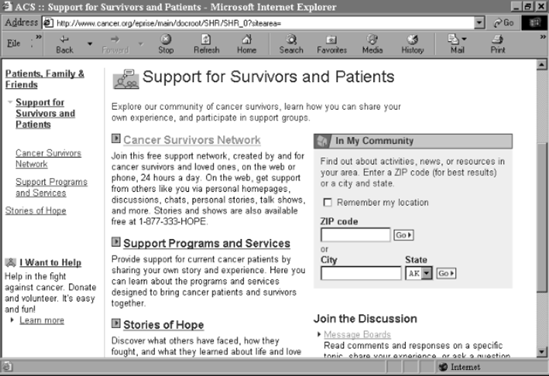

The American Cancer Society (ACS) recognized the importance of fostering a sense of community among cancer patients, survivors, their families, and ACS's donors and volunteers. Coping and survival are at the core of these groups' overlapping missions. So, in redesigning their Web site at cancer.org, they studied their users, especially cancer patients, to find out how best to provide them with connections to their most relevant support communities. They wanted to know how visitors to their site moved through it and where they would need links to community-enhancing features.

Most Web sites that include message boards segregate them under a "community" link that, if followed, leads the visitor to an environment quite different from that found elsewhere on the site. There is likely to be no information other than the topics and responses of the participants—a discussion ghetto. ACS wanted to weave the idea and the access to community throughout its site so that visitors, no matter where they were on the site, would have easy access to chat rooms or message boards. As Figure 9.10 shows, the site also links to compelling stories and an invitation to donate. ACS hopes to convert eager volunteers into eager donors.

In redesigning its site, ACS provided a good example of how to go about identifying the needs and tendencies of the user community. It hired a consulting company, Sapient, to help it with the analysis. As an article in CIO magazine12 described, Sapient "had clinical psychologists and cultural anthropologists spend time with cancer patients at various stages to develop an 'experiential model'." Based on that model, they imagined scenarios that would describe how different hypothetical individuals would move through the Web site.

Someone recently diagnosed with breast cancer would, for example, come to cancer.org looking for information about the disease, its prognosis, and its treatment. So links directing that person to that information should be prominent on the home page. Once informed, the patient would be interested in finding local support groups (see Figure 9.11) of breast cancer patients and survivors. A place for the patient to enter her zip code also would be located on the home page, as would links to general information about breast cancer. The patient, at this point, would be looking for an opportunity to ask questions, so links to chat rooms and message boards also would be posted on the home page. The invitation to join a network also offers the option of connecting by telephone for those who prefer that medium to online conversation.

Figure 9.10. The American Cancer Society's site directs visitors to appropriate conversations in its message boards.

Reprinted with the permission of The American Cancer Society, Inc.

ACS is devoted to supporting patients and families in their dealings with the disease and its aftermath, so its design keeps evolving to better support that purpose. The organization also expects to reap some bottom-line benefits from helping people share knowledge and caring. They hope to grow relationships with people that will lead them to donate to the organization, if not in money then in volunteer time. If the Web site and its communities can build a sense of loyalty among members, ACS can expect some of them to be regular supporters of the organization. And as James Miller, ACS's director of Internet strategy, put it, "that means you're always going to be at the top of a person's mind when they start thinking about donations."