2The organizational

context

Increasingly, the trend in organizational design today is towards smaller, more autonomous business units. Evidence for this trend takes several forms:

![]() replacement of traditional hierarchies, with all decisions taken at the centre, by decentralization of decision-making

replacement of traditional hierarchies, with all decisions taken at the centre, by decentralization of decision-making

![]() the incorporation of support services (like finance and personnel) into the activities of business units

the incorporation of support services (like finance and personnel) into the activities of business units

![]() the fragmentation of multiple product-lines into single-product activities, either for manufacture, marketing, or both.

the fragmentation of multiple product-lines into single-product activities, either for manufacture, marketing, or both.

The arguments for this approach (which is commonly called decentralization or federalism) are that:

![]() hierarchical organizations are ponderous and slow to react. As we shall see later in this chapter, speed of response to change is now critical to organizational survival and success.

hierarchical organizations are ponderous and slow to react. As we shall see later in this chapter, speed of response to change is now critical to organizational survival and success.

![]() centralized control reduces motivation and innovation. Employee expectations have changed from a comparative willingness to follow orders and instructions to the expectation that they will be consulted and involved in decisions.

centralized control reduces motivation and innovation. Employee expectations have changed from a comparative willingness to follow orders and instructions to the expectation that they will be consulted and involved in decisions.

![]() multilevel organizations are excessively costly. Questions are now being regularly asked about the costs and benefits of layers of management and the contribution of support functions.

multilevel organizations are excessively costly. Questions are now being regularly asked about the costs and benefits of layers of management and the contribution of support functions.

![]() decisions taken at the centre are divorced from both customers and staff. Put more strongly, this argument is simply that decisions taken at the centre are divorced from reality!

decisions taken at the centre are divorced from both customers and staff. Put more strongly, this argument is simply that decisions taken at the centre are divorced from reality!

Symptoms of this move from centralized to decentralized decision-making are:

![]() a heavy emphasis on ‘empowerment’ of all staff in the organization. We shall return to this them e in Chapter 10 of this book.

a heavy emphasis on ‘empowerment’ of all staff in the organization. We shall return to this them e in Chapter 10 of this book.

![]() extensive ‘delayering’, by removing layers of management and pushing the responsibility for decision-making lower down the organization.

extensive ‘delayering’, by removing layers of management and pushing the responsibility for decision-making lower down the organization.

![]() the recognition of colleagues and other functions in the organization as ‘internal customers’. This approach makes everyone in the organization responsible for identifying and satisfying customer needs.

the recognition of colleagues and other functions in the organization as ‘internal customers’. This approach makes everyone in the organization responsible for identifying and satisfying customer needs.

![]() the delegation of budgets and operational control to far more junior staff than was traditionally the case.

the delegation of budgets and operational control to far more junior staff than was traditionally the case.

CASE STUDY

In Mazda – and this is typical of most Japanese carmanufacturers – all production workers are entitled to stop the line if they consider that production quality is not satisfactory. It is then the responsibility of the workers – operating as a Total Quality team – to identify and resolve the problem.

The picture which emerges from all this is of small groups of contented staff happily managing their own working lives without the need for centralized guidance or direction. And if you think that sounds too good to be true, you would be right!

![]() What risks can you see in a move to decentralized decision-making?

What risks can you see in a move to decentralized decision-making?

![]() What else needs to happen to make sure it is effective?

What else needs to happen to make sure it is effective?

THE RISKS OF DECENTRALIZATION

The trend we have described appears to offer several benefits – to staff, customers and the organization alike. Indeed, it is a central them e of many of the ‘excellence’ texts published in the 1980s. For example:

On the other hand, we have the excellent companies. They are big. They have enviable records of growth, innovation and consequent wealth. Clearly, the odds are stacked against them . Yet they do it just the same. Perhaps them most important element of their enviable track record is an ability to be big and yet to act small at the same time. A concomitant essential apparently is that they encourage the entrepreneurial spirit among their people, because they push autonomy remarkably far down the line …(T. J. Peters and R. H. Waterman, In Search of Excellence, Harper and Row, 1982)

We have not so far been able to find an example of a highly successful British manufacturing company with a heavily centralized organization.

(W. Goldsmith and D. Clutter buck, The Winning Streak, Penguin, 1984)

But it would be a mistake to assume that them move from centralized control to autonomous operation is risk-free.

Experience shows that the risks fall into four categories:

![]() expectations

expectations

![]() expertise

expertise

![]() control

control

![]() co-ordination.

co-ordination.

Expectations

Under this heading, we need to consider both staff and customer expectations. For most organizations, decentralization and increased autonomy are initiatives which postdate the arrival of staff members by many years. Recruited into an organization where decisions were taken by senior management and the employees’ job was to do as they were told, staff can often find that they are suddenly expected to take far more personal responsibility than was the norm when they joined.

CASE STUDY

The British factory of Continental Tyres was threatened with closure when it proved unable to match the quality and productivity of its European counterparts. The senior management mounted a factory-wide initiative to seek suggestions for improvement from staff at all levels. Whilst the initiative was generally welcomed, significant numbers of staff complained that they were being asked to do the thinking that management was paid to do.

Increased delegation may also not meet customer expectations. Customers who have come to expect attention from a senior manager often feel slighted if they are now to be attended by someone more junior.

CASE STUDY

In Marks and Spencer's Oxford Street store, junior managers used to take it in turns to pretend to be the Branch Manager, in order that customers with a complaint could speak to someone they considered to have the authority to deal with it.

Expertise

We have pointed out that increased operating autonomy often goes with The removal of layers of management. Whilst bringing cost benefits, this approach may also involve the loss of valuable expertise and experience.

In order to cut costs, one of the UK's high street banks offered early retirement to a large group of long-standing Head Office managers. However, it then found that no one was left who had the experience to take the decisions for which they had been responsible. As a result, the bank was forced to hire back some of its retired managers on consultancy contracts.

In addition, the removal of central support functions may require remaining managers to take on specialist responsibilities – for example, the implementation of contract terms – for which they lack the expertise.

Control

We have already mentioned the argument in favour of decentralization: that centralized control reduces motivation and innovation. This does not change the fact that operational control remains an essential activity. Delegated or decentralized control brings the risk that different parts of the business will operate different or inconsistent standards, there by leading to our fourth risk.

Co-ordination

Poor co-ordination between operating units leads to two distinct problems. The First can sometimes be turned into an advantage. The second never can.

The first problem relates to the perception of the organization by the customer. If different parts of the organization offer different standards, prices and quality, whilst attempting to promote itself as a consistent whole, its image will suffer and it will be extremely difficult to formulate and promote a marketing message which can reconcile the inconsistencies.

Some organizations, however, take advantage of such inconsistencies by positioning different brands at different price or quality points in the market. The motor trade offers several excellent examples of this.

CASE STUDY

When Toyota made the strategic decision to enter the luxury car market, it established through market research that the Toyota name was too closely identified with smaller family cars to be carried by a luxury model. It therefore developed the Lexus brand, which is applied exclusively to it stop-of-the-range cars.

Jaguar is owned by Ford. However, the brand is sold through different outlets and, until the recent decision to build the X400 baby Jaguar at Ford's Halewood plant, was produced at different factories. Even the X400 production line at Halewood is to operate to different quality standards, and to be staffed by different and specially trained production workers from the Ford lines.

Volkswagen (VW) took advantage of the opportunity to invest in Eastern Europe by buying Skoda. Although new Skoda models have benefited from Volkswagen design and common components, VW has deliberately positioned Skoda at a different price point, thus giving access to two separate markets.

![]() The second co-ordination problem, however, is inherently obvious from the three examples we have quoted. In each case, the decision to offer different brands with different characteristics resulted from a strategic plan formulated and co-ordinated at the highest level of the company. So, for example, the price and quality differences between Toyota and Lexus didn't just happen – they were deliberately planned and implemented. It is clear that There is a limit beyond which decision-making and autonomy cannot bed elegated, if the organization is to implement a coherent strategy. Or, to put it more simply: someone at the top needs to take the big decisions

The second co-ordination problem, however, is inherently obvious from the three examples we have quoted. In each case, the decision to offer different brands with different characteristics resulted from a strategic plan formulated and co-ordinated at the highest level of the company. So, for example, the price and quality differences between Toyota and Lexus didn't just happen – they were deliberately planned and implemented. It is clear that There is a limit beyond which decision-making and autonomy cannot bed elegated, if the organization is to implement a coherent strategy. Or, to put it more simply: someone at the top needs to take the big decisions

What counts as ‘the big decisions’ appears to vary from sector to sector. As an example of this, it is worth returning to Goldsmith and Clutterbuck's The Winning Streak for a moment. Our earlier quote from this book is part of a longer section. Here it is in full:

In our sample of companies we have, with minor exceptions, two camps. At the one extreme are the decentralists, who operate as federations of independent small units. At the other end are the centralists, who have large functional departments at headquarters and very limited autonomy at operating level. With one exception, the centralists are all retailers; we have so far not been able to find an example of a highly successful British manufacturing company with a heavily centralized organization.

This centralized decision-making in multisite retailing is designed to achieve consistency in design, image, presentation, stock and pricing. As a ridiculous example, just picture the customer confusion and irritation if Boots had a blue fascia in one town but red in another, sold toothpaste in one store but not in another and charged different prices for the same item in different branches!

Of course, the same does not apply to manufacturing. Here, it is reasonable for operations managers in different locations to make their own decisions about the external sourcing of components – which suppliers to use and the price and delivery details of the contract – and even about the wages to pay, if one factory is in a high-cost area with low unemployment and another in a low-cost area with high unemployment. Nevertheless, the need for co-ordination still applies. If different factories are producing the same product, mechanisms need to exist to ensure that the product does the same job and meets the same standards, regardless of where it comes from.

CASE STUDY

Jacob's Biscuits used to manufacture the same product at factories in both England and Southern Ireland. The Irish biscuits were both cheaper and of higher quality. The company tried, but failed, to achieve consistency between the two products. Total production for that line was then concentrated in Southern Ireland.

In most cases, operational co-ordination in charities is limited. Dependent largely on volunteers, charities are willing to sacrifice consistency in favour of delegated decision-making. Nevertheless, There are exceptions. A few years ago, Oxfam made a significant financial investment to achieve consistency in the image and decor of its high street outlets. This was not a painless exercise. Many supporters objected that the money spent on upgrading the shops should have been allocated directly to the Third World causes which Oxfam exists to help.

Government departments are a totally different matter. It would be wholly unacceptable, for example, if income tax or VAT were calculated in different ways in different parts of the country. The Civil Service approach to ensuring consistency in such activities is to publish detailed procedure or operations manuals, which specify exactly what processes to follow and how calculations should be made. Nevertheless, even in the Civil Service There is a growing trend towards delegated decision-making.

In the past, little attempt was made to co-ordinate the activities of individual schools and hospitals. However, things have changed. The introduction of performance league tables for schools and of freedom for GPs to choose where to send patients for hospital treatment is intended to achieve greater consistency of performance by bringing the performance of the worst up to the standard of the best.

EFFECTIVE DECENTRALIZATION

The keys to effective decentralization are remedies to the risks we have already described. In order to address the issue of staff and customer expectations, the following are important:

![]() Ensure that staff recognize the nature and responsibilities of their jobs. For new staff, this is relatively straightforward. It involves preparing job descriptions which are accurate and realistic, evaluating each job and ensuring that wage or salary levels are competitive with those on the wider job market.

Ensure that staff recognize the nature and responsibilities of their jobs. For new staff, this is relatively straightforward. It involves preparing job descriptions which are accurate and realistic, evaluating each job and ensuring that wage or salary levels are competitive with those on the wider job market.

For existing staff, the process is more demanding. It may require jobs to be redefined, re graded and pay adjusted. It is not adequate simply to assume that staff will be satisfied purely with the challenge of greater responsibility.

![]() Recognize and address the need for training. Countless ‘empowerment’ initiatives have failed as a result of crediting staff with the instinctive ability to make decisions and implement improvements, after years during which such instincts have been treated as a disciplinary offence.

Recognize and address the need for training. Countless ‘empowerment’ initiatives have failed as a result of crediting staff with the instinctive ability to make decisions and implement improvements, after years during which such instincts have been treated as a disciplinary offence.

![]() Implement a change in management style. The traditional ‘command and control’ style expects obedience without question and penalizes mistakes. By contrast, delegated decision-making involves a willingness for judgements to be questioned, and mistakes to be made, in pursuit of improvement and innovation. Clifford and Cavanagh ( The Winning Performance, Sidgwick and Jackson, 1985) quote the following example:

Implement a change in management style. The traditional ‘command and control’ style expects obedience without question and penalizes mistakes. By contrast, delegated decision-making involves a willingness for judgements to be questioned, and mistakes to be made, in pursuit of improvement and innovation. Clifford and Cavanagh ( The Winning Performance, Sidgwick and Jackson, 1985) quote the following example:

At MCI, the ‘other’ long-distance telephone company, making and learning from mistakes seems to be a central part of them anagement catechism. We interviewed twenty-five senior managers at MCI to discern the criticalelements of its corporate culture. The first conversation was with Bill McGowan, the chief executive, who, after answering our questions, concluded the interview by saying: ‘Don't forget, we make a lot of mistakes around this place. Have from the beginning. But so long as somebody doesn't keep making the same mistake over and over again, we can live with it and recover …’. What distinguishes the way these winning companies manage mistakes is that they make them on a small scale, encourage lots of experiments and dedicate their energy to fixing them rather than attributing fault.

![]() Communicate with customers. As with any marketing initiative, moving customer responsibility further down the organization needs customers to understand the benefits. They ’ll have easier and quicker access. The individual concerned will understand their needs better. Actions and decisions will be taken more quickly.

Communicate with customers. As with any marketing initiative, moving customer responsibility further down the organization needs customers to understand the benefits. They ’ll have easier and quicker access. The individual concerned will understand their needs better. Actions and decisions will be taken more quickly.

Delegating customer contact may be a cost saving or an efficiency measure. It may be because the person who used to have that responsibility has been made redundant – the job has disappeared. But that is all bad news which should remain internal. If you're going to sell the change, find the good news which benefits the customer.

The matter of expertise can be resolved primarily by not getting carried away by management theory! Delayering and delegated decision-making are not automatic sources of performance improvement. Rather, their effectiveness depends on a careful analysis of:

![]() the operational processes and control systems in place

the operational processes and control systems in place

![]() the nature and culture of the business

the nature and culture of the business

![]() the quality and experience of the staff.

the quality and experience of the staff.

So, for example, in a manufacturing business where production processes are simple, effective systems exist to monitor quality and output, and junior staff are familiar with the processes, the removal of layers of management is likely to be successful.

LMG Packaging produces printed paper and plastic packaging for a range of industries, including food and medical supplies. In order to upgrade its production technology, the company bought new, computer-controlled machines from Italy. The machines incorporated a range of devices to monitor production tolerances, the outputs from which appear on screens attached to them achines. The company trained its machine operators to interpret the displays and make adjustments based upon them – a task which had previously been done by team leaders on the old manually controlled machines. They were thus able not only to enlarge them achine operators’ jobs, but also to restructure the teams, reducing the number of team leaders through transfer and natural wastage.

On the other hand, in a sophisticated business with complex processes, where control is exercised by experienced supervisors but junior staff are not very capable, the cost of introducing new control systems and, quite possibly, recruiting a new cohort of junior staff, may well make it preferable to stick with multiple levels of management, regardless of what the textbooks say!

We have already introduced the subject of control. Effective control starts by finding answers to the following questions:

![]() What are the critical success factors in the business, or in the part of the business for which I am responsible?

What are the critical success factors in the business, or in the part of the business for which I am responsible?

![]() What do my customers expect from me?

What do my customers expect from me?

![]() How can those success factors and customer expectations be translated into measurable objectives?

How can those success factors and customer expectations be translated into measurable objectives?

![]() What monitoring systems will be necessary to measure performance against objectives?

What monitoring systems will be necessary to measure performance against objectives?

![]() What performance tolerances will be acceptable?

What performance tolerances will be acceptable?

Quantitative objectives are relatively easy to set and measure: machine output, gross and net profit, calls made or business won per salesperson, for example. Qualitative objectives are less easy. How do you measure:

![]() the relevance and effectiveness of training?

the relevance and effectiveness of training?

![]() customer satisfaction?

customer satisfaction?

![]() staff motivation?

staff motivation?

Stop for a moment to see if you can think of operational controls which would measure those three factors, then compare your answers with ours:

![]() Relevance and effectiveness of training. Most training operations use some kind of ‘happy sheet’ at the end of a training event. Typically, these ask delegates whether the event was relevant to their needs using a scale like that in Figure 2.1, which can be translated into numbers.

Relevance and effectiveness of training. Most training operations use some kind of ‘happy sheet’ at the end of a training event. Typically, these ask delegates whether the event was relevant to their needs using a scale like that in Figure 2.1, which can be translated into numbers.

Figure 2.1

The effectiveness of training cannot be assessed at the event itself. The measurement of the factor requires a monitoring process which asks managers to assess the trainee's performance before and after the event. Provided that them anager is given descriptions of performance at different standards (’mastery’, ‘excellence’, ‘competence’, ‘needs improvement’, ‘needs considerable improvement’, for example) it is again possible to quantify the results.

![]() Customer satisfaction. A number of indirect measures can be applied to this factor. For example:

Customer satisfaction. A number of indirect measures can be applied to this factor. For example:

![]() numbers of complaints

numbers of complaints

![]() volume of repeat business

volume of repeat business

![]() regular customer satisfaction surveys.

regular customer satisfaction surveys.

![]() Staff motivation. This factor can be measured indirectly by recording:

Staff motivation. This factor can be measured indirectly by recording:

![]() staff turnover

staff turnover

![]() length of service

length of service

![]() numbers of grievances

numbers of grievances

![]() absentee levels

absentee levels

![]() days lost due to industrial action.

days lost due to industrial action.

Success factors, customer expectations, measurable objectives and monitoring systems are all important issues. However, the internal customer makes customer expectations the most critical.

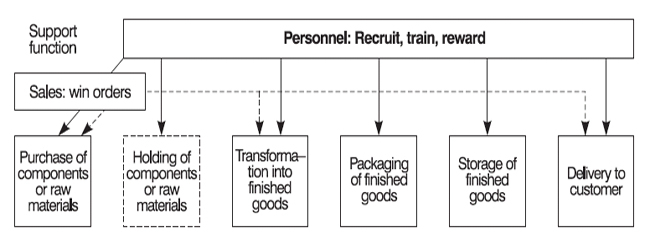

Which brings us to the issue of co-ordination. As we shall see in more detail in Chapter 4 of this book, operations management adds value to the final customer by spanning a range of functions, as the manufacturing diagram in Figure 2.2 makes clear.

Figure 2.2 the manufacturing process

As we explained in Chapter 1, the sales or marketing function promotes the product, builds customer desire for it, sells it and takes the order. This in turn results in manufacturing activity. However, the factory is also dependent on the components or raw materials bought by the purchasing function. Finished goods are then packaged, held in the warehouse, then delivered to the customer.

The need for co-ordination throughout this process is obvious:

![]() The factory needs to know from sales how much of each product to make.

The factory needs to know from sales how much of each product to make.

![]() Purchasing needs to know the factory's production schedule, in order to buy the right quantities of components or raw materials to make them available at the right time.

Purchasing needs to know the factory's production schedule, in order to buy the right quantities of components or raw materials to make them available at the right time.

![]() The warehouse needs to know what to deliver, when and to whom.

The warehouse needs to know what to deliver, when and to whom.

As we mentioned earlier, operations management takes place at both a macro and a micro level. Chapter 3 describes the micro operations which are necessary to ensure the continuous availability of the right resources.

We shall now consider the involvement of operations management in ‘ the big picture’ planning – the development of strategy.

STRATEGY, MISSION AND GOALS

Theodore Levitt, the well-known American management guru, once said: ‘If you don't know where you're going, any road will take you the re.’ This seems obvious. It implies that, unless an organization is clear, at least in general terms, about what it exists to do, the customers it intends to serve, the products and services it will offer and how big it wants to be, it will be impossible to take meaningful decisions and actions related to:

![]() resources

resources

![]() budgets

budgets

![]() product and service quality

product and service quality

![]() staffing levels

staffing levels

![]() staff quantity, training, expertise and reward.

staff quantity, training, expertise and reward.

It is therefore surprising that research continues to show that a high proportion of organizations – particularly in the small and medium-sized categories – continue to operate on a ‘hunch and gut feel’ basis.

Equally surprising is the fact that so many operations do indeed follow a strategic planning process, but fail to achieve their goals. A recent survey found that 70 per cent of businesses had failed to achieve their merger and acquisition objectives and 79 per cent had failed to implement the customer service initiatives contained in their plan.

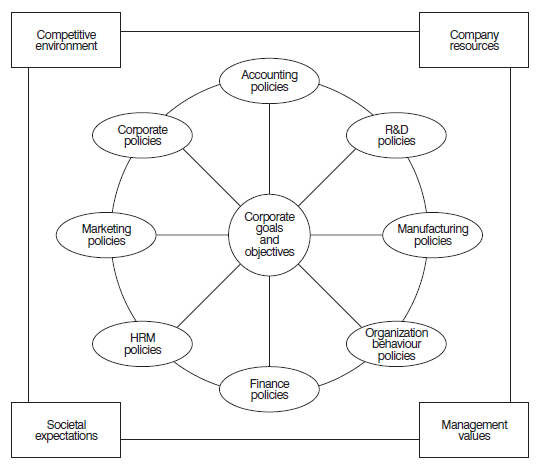

So how should the strategic planning process work? Francis J. Kelly and Heather Mayfield Kelly, in their book What they Really Teach You at the Harvard Business School (Piatkus, 1987), describe the Harvard approach as follows:

The first step in developing a strong business-policy analysis is to identify and analyse the ‘immovable object‘ elements in the environment in which a decision is being made – the elements over which one has no control. These are called fixed elements.The se elements, which cannot be manipulated by management, form the constraints within which management must operate ... First, the competitive environment must be assessed. Companies must determine what business they are in and who the main competitors are … after analysing the competition, carefully assess your own company's resources. What are the company's major strengths in relation to its competitors – product quality? Lower cost? Marketing clout? Greater financial resources? What are its major weaknesses – product quality? Distribution? Sales force? The best corporate strategies are those that draw upon a company's strengths while minimizing its weaknesses.

Third, society's expectations for the enterprise must be analysed. Does society expect the firm to reap huge profits? Pay a lot in taxes? Provide jobs? Invest locally? What will anger society? How important is public opinion, especially bad public opinion? Will it affect company performance? ...

Management values is another important area that needs analysis. In what direction will the values of its management lead a company? What directions will they prohibit? Does management most value growth and profits or is a stable live able work environment more important? Is performance most valued or honesty and loyalty to the company? …

Given the constraints placed on a company and outlined in the fixed elements analysis, management must then work with them any variables over which it does have control to construct its business policy. These controllable elements must be analysed in order to create the best possible corporate strategy for a particular company, given its unique position in the marketplace.

Marketing policies must be analysed. What should the company produce? How should these products be positioned? How should they be priced? What is the best way to distribute those products? How should the product be advertised and promoted?

Manufacturing policies need careful attention. What type of manufacturing process is best to produce the type and quantity of products the company desires? Where should manufacturing and distribution facilities be located? Should the company manufacture continually or season-ally? What role will new technologies play in operations?

Integrated financial policies must be developed. What performance goals does the company want to set in terms of profits, operating margins, and return on capital? Will the company's funds come from operations, debt or equity? How much ownership will management retain? How much will employees own? How much will the public own?

Research and development policies must also beset. What percentage of sales will be ploughed back into R&D? Will R&D effort be long-term in nature or more short-term/application-oriented? Will R&D be done for the whole company at the corporate level or will it be done within each division? Who will manage R&D operations? Are R&D joint ventures in the firm's best interest?

Human resources policies are also critical. What type of people will the company seek to employ? How will employees be compensated? Will salaries be high or low? Will compensation be all salary or less salary and greater opportunities for bonuses? Issues of corporate structure must be investigated. How will the company be structured to maximize success in the marketplace?

The diagram resulting from these two stages of analysis (fixed element analysis, controllable element analysis) is shown in Figure 2.3.

Figure 2.3 A framework for strategic decision-making

This model – and the questions and issues raised by the Harvard process- are broadly consistent with other strategic planning models. And, although there are references throughout to manufacturing and trading companies, you should have no difficulty in recognizing those which are relevant to your organization, whatever its reason for existence may be.

Operations management and strategic planning

You may be wondering what the strategic planning process has to do with you. There are two answers to this, each of which is inherent in points already made in this book.

Top-down and bottom-up planning

In a traditional hierarchy, strategic decisions were taken by top management and passed down through the organization for implementation. This is the old ‘command and control’ culture previously mentioned.

Nowadays, though, organizations are recognizing that all strategic decisions have operational consequences, at both a macro and a micro level. And, at the micro level, it is the staff closest to the action who are likely to be best placed to decide what is possible and what should be done.

It is not suggested that strategic plans should be simply an accumulation of micro-level operational plans. The lack of co-ordination and cross-functional consistency which would result from such an approach would be devastating: all the bits of an organization would be pulling in different directions.

Instead, the modern response to strategic planning is to combine a top-down with a bottom-up approach. In other words, senior management fixes the mission of the organization – a short, clear statement in answer to the question: ’What is our reason for existence?’ they are also likely to set the values for the organization – its duties and obligations to the various stakeholders (staff, customers, suppliers, the community) on which it depends.

These statements of mission and values are then passed down, with individual functions being asked to consider what they can achieve to deliver them ission, in line with the values. Of course, this is a messy process. It is likely to take several interactions before all the inconsistencies between functions have been resolved. Nevertheless, it does mean that the resulting plans will be realistic, achievable and consistent.

Motivation and co-ordination

There are two approaches to decision-making in any organization: procedures and values.

The first approach is centralized. It involves those at the centre working out all the decisions which colleagues in the line will be required to make and formalizing the form those decisions should take through books full of rules and procedures. Traditionally, this has been the approach taken by the Civil Service and retail businesses to achieve consistency.

CASE STUDY

Every outlet of the Waitrose supermarket chain has its own training room. Each room is lined with training materials specific to Waitrose. These deal with every issue, from how a till operator should give change, to how to deal with a suspect credit card, to how to calculate leave entitlement, to what to do in case of an out-of-hours break-in. Each situation is described in detail and a clear and detailed set of instructions given for handling it.

The alternative ‘values’ approach is epitomized by the IBM ‘Blue Book’.

CASE STUDY

IBM, known traditionally as ‘Big Blue’ because of its corporate colours, publishes a slim pamphlet of organizational values. These are based on the principles followed by Thomas J. Watson, the company's founder. There were originally just three of them :

![]() Give full consideration to the individual employee

Give full consideration to the individual employee

![]() Spend a lot of time making customers happy

Spend a lot of time making customers happy

![]() Go the last mile to do a thing right.

Go the last mile to do a thing right.

Over time, these three principles have been extended and formalized. Nevertheless, when faced with a difficult decision, it is to this slim pamphlet of values rather than to a manual of procedures that IBM executives turn.

This ‘values’ approach is in line with the philosophy of decentralization we have already discussed. From a motivation viewpoint, it allows people to adopt a proactive method of decision-making and thereby feel that they are a sponsible member of the organization. In terms of co-ordination, it provides a simple and non-bureaucratic way of achieving and maintaining consistency. Nevertheless, the approach has its dangers. Organizational values are only meaningful if they are exemplified by behaviour as well as by being published. Values will only be understood and properly applied if they are modelled consistently by colleagues and managers.

ENVIRONMENTAL DEMANDS AND CONSTRAINTS

The strategic planning process we have already described starts with an analysis of the environment in which the organization operates. The management literature describes the factors to be considered as:

![]() political

political

![]() economic

economic

![]() social

social

![]() technological

technological

![]() legal

legal

![]() environmental.

environmental.

Political factors

Political actions and decisions may open or close markets, that is, make them less or more attractive. If you work for a not-for-profit organization, these actions may change your tax situation or influence the demand for your services. If, historically, yours has been a government operation or nationalized industry, political decisions may change your status.

Economic factors

The level of economic success, whether international, national or local, will influence:

![]() customer spending power

customer spending power

![]() the advisability of expansion

the advisability of expansion

![]() the nature of demand

the nature of demand

![]() the availability of funding

the availability of funding

![]() the reward structure necessary to attract staff.

the reward structure necessary to attract staff.

Social factors

Social changes may:

![]() increase or decrease your customer base

increase or decrease your customer base

![]() change your customer profile and their requirements from you

change your customer profile and their requirements from you

![]() affect staff availability

affect staff availability

![]() influence your physical distribution network.

influence your physical distribution network.

Technological factors

Technology may:

![]() change the nature of your products and services

change the nature of your products and services

![]() increase or decrease the demand for them

increase or decrease the demand for them

![]() affect the way they are produced

affect the way they are produced

![]() affect the way they are delivered

affect the way they are delivered

![]() influence their costs

influence their costs

![]() influence their value.

influence their value.

Legal factors

Legislation may impact on what your organization is allowed and not allowed to do. New legislation could change:

![]() working practices

working practices

![]() customer rights and expectations

customer rights and expectations

![]() employee rights and expectations

employee rights and expectations

![]() community rights and expectations.

community rights and expectations.

Environmental factors

Interpreted as ‘care for the physical environment’, environmental influences affect a range of organizational considerations, including:

![]() the choice of raw materials

the choice of raw materials

![]() manufacturing methods

manufacturing methods

![]() choices of physical distribution channels

choices of physical distribution channels

![]() the format of packaging

the format of packaging

![]() energy usage.

energy usage.

Depending on your place and responsibility in the operations management process and the sector in which you work, you may be called on to:

![]() assess the impact of a political decision

assess the impact of a political decision

![]() implement a budget affected by political considerations

implement a budget affected by political considerations

![]() increase or decrease production in line with market demands

increase or decrease production in line with market demands

![]() take account of social factors when recruiting staff

take account of social factors when recruiting staff

![]() implement or use new technology

implement or use new technology

![]() make technological changes to existing products

make technological changes to existing products

![]() implement new working practices as a result of changes to legal requirements

implement new working practices as a result of changes to legal requirements

![]() change the raw materials you use or the way you dispose of waste

change the raw materials you use or the way you dispose of waste

![]() achieve energy savings.

achieve energy savings.

At the very least, you will find it helpful to understand the environmental considerations which have led to the decisions you are required to implement. At the other end of the scale, it may be part of your role to contribute to those decisions.

THE HIERARCHY OF DECISIONS

We have already stated the argument that operational decisions should be taken by people closest to the point of impact. However, this is another piece of management theory which is not always supported by organizational reality!

Referring to a more hierarchical approach to decision-making, Rosemary Stewart ( The Reality of Management, Butterworth-Heinemann, 1997) quotes research by the American academic Norman Martin. She explains:

Norman Martin looked at the different levels of management in a large American manufacturing company. He found that the decision situation differed in a number of ways between the levels. By ‘decision situation’ Martin meant the whole range from the preliminary stages, through the actual decision and implementation to verification of the correctness or incorrectness of the decision.

The main differences he discovered were in the length of the time perspective, the amount of continuity and the degree of uncertainty. Decisions at the higher levels have as one would expect a longer time perspective. From first inquiry to verification of the decision took less than two weeks in 97.7% of the shift foreman's decision situations; 68% of the department foreman's decision situations were completed within two weeks; 54.2% of the division superintendent's; and only 3.3% of the works manager's. Half of the works manager's decision situations lasted over a year; 4.3% of the division superintendent's, 1.5% of the department foreman's and none of the shift foreman's. This shows the striking difference in distant-time perspective between the works manager and the otit would depend upon her three levels of management. Decisions at the higher level tended to be discontinuous as one would expect with a long time span. There were sometimes wide gaps between the different parts of the decision situation, partly due to the manager having delegated part of the process of carrying through a decision to his subordinates. At the lower levels all the stages tend to follow each other without a time interval, or with only a short one.

The decisions at the lower levels were much more clear cut. What had to be done was more easily seen, it usually had to be done quickly and There was less uncertainty about the result than at higher levels. At the higher levels the decision situation was much more indefinite; the time within which action should be taken was often indeterminate as it would depend upon the judgement of the total situation; what should be done was often difficult to decide because There were so many elements of uncertainty in the decision.

It would be a mistake to place too much emphasis on the detail of this research. But it would equally be a mistake to overlook the broad findings it contains. In simple terms, these can be summarized as:

![]() High-level decisions take a long time to take, implement and evaluate.

High-level decisions take a long time to take, implement and evaluate.

![]() High-level decisions are discontinuous, with time gaps between the various stages.

High-level decisions are discontinuous, with time gaps between the various stages.

![]() High-level decisions involve considerable uncertainty about the nature of the issue to be resolved and the likely success of the action decided on.

High-level decisions involve considerable uncertainty about the nature of the issue to be resolved and the likely success of the action decided on.

Those three points have significant implications for decision-making in operations management. When faced with an operational decision, ask yourself:

![]() How much do you know about the issue to be resolved?

How much do you know about the issue to be resolved?

![]() What are the causes? Are you sure?

What are the causes? Are you sure?

![]() If not, who of your colleagues or subordinates could tell you more?

If not, who of your colleagues or subordinates could tell you more?

![]() How complete is the evidence you currently have?

How complete is the evidence you currently have?

![]() What would an effective decision look like?

What would an effective decision look like?

![]() What must the solution achieve?

What must the solution achieve?

![]() How would you measure success?

How would you measure success?

![]() What are the limits to your decision?

What are the limits to your decision?

![]() What are your limits of authority?

What are your limits of authority?

![]() What other constraints limit your choice of solution? (For Example, time, cost, resource availability, expertise, legal constraints)

What other constraints limit your choice of solution? (For Example, time, cost, resource availability, expertise, legal constraints)

![]() What alternative decisions or solutions are open to you?

What alternative decisions or solutions are open to you?

![]() How well would each satisfy the objectives an effective decision must achieve?

How well would each satisfy the objectives an effective decision must achieve?

![]() How far does each fit within the limits you have identified?

How far does each fit within the limits you have identified?

![]() If the decision exceeds your limits of authority, who is authorized to take it?

If the decision exceeds your limits of authority, who is authorized to take it?

![]() Your boss?

Your boss?

![]() Another department?

Another department?

![]() What evidence, information and guidance will they need?

What evidence, information and guidance will they need?

![]() About the issue?

About the issue?

![]() About the alternatives?

About the alternatives?

![]() About the risks?

About the risks?

![]() About the necessary resources?

About the necessary resources?

![]() About the likely success of your proposed solution?

About the likely success of your proposed solution?

![]() Once the decision has been taken, how will you measure it ssuccess?

Once the decision has been taken, how will you measure it ssuccess?

![]() Has the issue been resolved?

Has the issue been resolved?

![]() How much did it cost?

How much did it cost?

![]() How long did it take?

How long did it take?

![]() What resources did it consume?

What resources did it consume?

We can summarize these questions in the form of the decision-making model shown in Figure 2.4.

You will notice that the model does not incorporate the referral of the problem to someone else in the organization. This is for two reasons. First, inline with the philosophy of delegated decision-making, we would prefer to believe that those who have recognized an issue will be given the authority to deal with it.

Secondly, we recognize that the reality of operational decision-making isn't always like that. As a consequence, we cannot be sure whether the culture of your organization will require you to refer an issue as soon as you have defined it. (Box 1 in Figure 2.4), or when you have recognized that it is outside your limits of authority (Box 3), or when you have identified some options (Box 4), or when you want agreement to implement a preferred solution (Box 5).

Figure 2.4 A model for decision-making

If you have the authority to deal with issues which affect you or your team, this problem does not apply. If, on the other hand, There are limits to the decisions you can take, it will be important for you to remember to present sound evidence and reliable information to whomever you want to support you.

COMPETENCE SELF-ASSESSMENT

1 Does your organization practise centralized or decentralized decision-making?

2 How consistent is that approach with staff and customer expectations, available expertise, the need for control and co-ordination?

3 How effectively does your organization control its operations?

4 How much do you know about your organization's strategy, mission and goals?

5 How would you find out more about them to be more effective in your job?

6 To what extent do environmental factors impact on the work you do?

7 How could you find out more about them ?

8 What are your limits of decision-making authority?

9 Faced with a decision which exceeds your authority, who would you go to?

10 How persuasive have your arguments been in the past? And how could you improve them in the future?