8Continuous

improvement

OBJECTIVES OF CONTINUOUS IMPROVEMENT

On an individual level, the search for continuous improvement appears to be part of our genetic conditioning. Just as fish developed legs and lungs in order to improve their chances of survival by moving onto the land, so today we seek to improve our personal situations by:

![]() gaining more qualifications

gaining more qualifications

![]() moving into a bigger house

moving into a bigger house

![]() making more friends

making more friends

![]() achieving promotion

achieving promotion

![]() boosting our reputations

boosting our reputations

![]() impressing the boss.

impressing the boss.

Arguably, through all these activities, we are following the Darwinian principle of ‘the survival of the fittest’.

‘Now hold on’, interrupted the cynical accountant from our earlier debates. ‘Darwin concluded that we improve in order to survive, not that we survive in order to improve. You seem to be suggesting that continuous improvement should be a way of life, regardless of need – or cost!’

There are two sides to the argument about continuous improvement. By some, it is promoted as the only justifiable approach to organizational life. Current systems and methodologies are never good enough. There is always a better way. The best is always around the corner.

Some organizations that have adopted continuous improvement as a watchword take this approach. However, it is at variance with the management gurus from the relevant literature:

To maintain a wave of interest in quality, it is necessary to develop generations of managers who not only understand but are dedicated to the pursuit of never-ending improvement in meeting external and internal customer needs. (John S. Oakland, Total Quality Management, Butterworth-Heinemann, 1989)

The need for innovation on an unprecedented scale is a given. The question is how. It seems that giving the market free rein, inside and outside the firm, is the best – perhaps the only – satisfactory answer.

(Tom Peters, Liberation Management, Macmillan, 1992)

Technology and economics is a potent blend. It is the premise to this book that from that blend all sorts of changes ensue.

(Charles Handy, The Age of Unreason, Hutchinson, 1989)

Processes are how the organization delivers outputs to the customer. The closer the fit between what the customer wants and what you deliver, the more successful you are likely to be in securing and retaining customers. But as we have seen, organizations are operating in an environment of constant change – in the marketplace, in their immediate environment, in technology, and, most importantly, in what their customers want and expect from them. It is not enough simply to keep an eye on existing processes and solve the occasional problem. The goal posts are moving; so it is a question of constantly readjusting your aim to stay on target. (Teresa Riley, Understanding Business Process Management, Pergamon, 1997)

‘I'm all in favour of that’, commented our marketing manager. ‘If continuous improvement means bringing our products closer to what the customer wants, that makes my job easier. The products will be easier to promote. Customers will be more satisfied. Yes, I like that.’

The marketing manager is right, of course – but only up to a point. As you would expect from earlier contributions, he is missing important aspects of the total picture.

As pointed out earlier, continuous improvement is essential to organizational survival. But it is not simply to do with achieving a better fit between customer needs and the product or service provided by the operation, important though this is. In addition, continuous improvement is a process intended to:

![]() improve the match between the operation and the goals of the organization

improve the match between the operation and the goals of the organization

![]() reduce costs

reduce costs

![]() increase efficiency

increase efficiency

![]() reduce or eliminate waste

reduce or eliminate waste

![]() increase job satisfaction.

increase job satisfaction.

‘Ah, now you've got to it’, broke in the personnel officer. ‘In previous chapters of this book, you've gone on about the need to consult and involve staff. Well, believe me, not everyone finds continuous improvement satisfying. Improvement means change and, for a lot of people, change is difficult, unsettling. I'm all for increased job satisfaction – but don't pretend that continuous improvement is an unfailing route to it.’

This introduction to continuous improvement has put the topic into context. It is not simply a routine to be followed because that is the right way for up-to-date organizations to behave. Rather, it is a way of ensuring organizational survival by increasing customer satisfaction and competing more effectively. But only these two objectives are necessary to the survival of your organization. And continuous improvement is rarely painless – it brings risks, one of which is that of unsettling and alienating staff.

In the remainder of this chapter, we shall consider in greater detail:

![]() the needs for continuous improvement

the needs for continuous improvement

![]() the risks of continuous improvement

the risks of continuous improvement

![]() the process of continuous improvement

the process of continuous improvement

![]() the implications of continuous improvement.

the implications of continuous improvement.

Let us start with the arguments in favour.

THE NEED FOR CONTINUOUS IMPROVEMENT

The speed of change

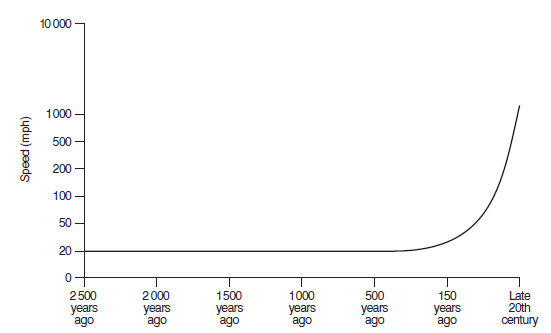

The speed of environmental change – particularly in the areas of economics, society, technology and competition – is a recurring theme in management literature. A frequently quoted example is that of transport. As Figure 8.1 shows, from the dawn of time and for thousands of years, humankind was limited to travel on foot – and a maximum running speed of some 10 miles an hour. Catching and riding a horse, the invention of the wheel and the design of horse-drawn chariots and carriages doubled that speed. Then, in the nineteenth century, the invention of the steam engine revolutionized transport, in terms of both the speeds which could be reached and the distances which could be covered. The rapid development of the internal combustion engine brought about a dramatic acceleration in the speed of transport, accentuated by its use to power aeroplanes, followed by the invention of jet engines and the introduction of rocket travel. In less than two centuries, the speed of transport has increased from about 20 miles per hour to over twice the speed of sound.

Medical and biological technology offer similar examples. The twentieth century has seen the introduction of:

![]() open heart surgery

open heart surgery

![]() organ transplants

organ transplants

![]() antibiotics

antibiotics

![]() eyesight correction by laser treatment.

eyesight correction by laser treatment.

Figure 8.1Rate of change in transport. Adapted from T. Riley, Understanding Business Process Management, Pergamon, 1997.

Social change has also been rapid during this century. For example:

![]() an increase in divorce rates

an increase in divorce rates

![]() a move away from marriage to living together

a move away from marriage to living together

![]() a growing acceptance of homosexual couples

a growing acceptance of homosexual couples

![]() an increase in single parent families

an increase in single parent families

![]() couples starting families later in life

couples starting families later in life

![]() a growth in home working.

a growth in home working.

All these changes have had a major impact on what is technically possible in operations management and on customer expectations and market demands. Add to that increased industrialization in economies like those of India and the countries of the Pacific Rim, the growth of multinational companies and increased diversification, and the consequences for changes in competition are self-evident.

CASE STUDY

Tom Peters quotes the following from the preface to Liberation Management (Macmillan, 1992):

Recently I was talking to one of Japan's best foreign-exchange dealers, and I asked him to name the factors he considered in buying and selling. He said, ‘Many factors, sometimes very short-term, and some medium, and some long-term’. I became very interested when he said he considered the long term and asked him what he meant by that time frame. He paused a few seconds and replied with genuine seriousness: ‘Probably ten minutes.’ That is the way the market is moving these days.

It is obvious from all this that, as customer needs, wants and expectations are changing, available technology is changing, markets are changing and competitors and the nature of competition are changing, so organizations and operations need to change in response.

Continuous and discontinuous change

We need to distinguish here between two different types of change:

![]() continuous or incremental change

continuous or incremental change

![]() discontinuous change.

discontinuous change.

Recent management literature has placed considerable emphasis on the need to respond effectively to discontinuous change. Charles Handy in The Age of Unreason (Hutchinson, 1989) starts his book by writing:

The story or argument of this book rests on three assumptions:

![]() that the changes are different this time: they are discontinuous and not part of a pattern; that such discontinuity happens from time to time in history, although it is confusing and disturbing, particularly to those in power

that the changes are different this time: they are discontinuous and not part of a pattern; that such discontinuity happens from time to time in history, although it is confusing and disturbing, particularly to those in power

![]() that it is the little changes which can in fact make the biggest differences to our lives, even if these go unnoticed at the time, and that it is the changes in the way our work is organized which will make the biggest difference to the way we all will live

that it is the little changes which can in fact make the biggest differences to our lives, even if these go unnoticed at the time, and that it is the changes in the way our work is organized which will make the biggest difference to the way we all will live

![]() that discontinuous change requires discontinuous upside-down thinking to deal with it, even if both thinkers and thoughts appear absurd at first sight.

that discontinuous change requires discontinuous upside-down thinking to deal with it, even if both thinkers and thoughts appear absurd at first sight.

The proposition behind this emphasis on discontinuous change is that we can no longer predict the future by extrapolating from the present and the past. Past solutions will not be relevant to future problems. Hence Handy's reference to the need for ‘upside-down thinking’. Of course, failures to recognize discontinuous change have proved a major threat to many organizations.

CASE STUDY

IBM failed to notice the rapidly growing power and user-convenience of personal computers (PCs), preferring to remain with the mainframes which had traditionally been a totally reliable source of profit. They introduced PCs five years later, following a dramatic drop in mainframe sales which almost crippled the business.

The significance of discontinuous change on operations will be drastic – and significantly disruptive. It is likely to require:

![]() retooling and re-equipping to produce new products

retooling and re-equipping to produce new products

![]() the recruitment of new staff and retraining of existing staff to introduce new services

the recruitment of new staff and retraining of existing staff to introduce new services

![]() the abandonment of old systems and their replacement with new systems

the abandonment of old systems and their replacement with new systems

![]() the adoption of new philosophies and new attitudes

the adoption of new philosophies and new attitudes

![]() a redefinition of markets and customers

a redefinition of markets and customers

![]() entry into new markets and the abandonment of old markets.

entry into new markets and the abandonment of old markets.

Chapter 9 deals in more detail with responses to discontinuous change.

Risk management

Responses to continuous or incremental change are the central theme of continuous improvement. Nevertheless, there are some basic principles which underpin both sets of responses. Vincent Nolan in his book The Innovator's Handbook (Sphere, 1987) relates change and improvement to the issue of risk. He explains:

Probably the most important difference between innovative and routine management lies in the attitudes toward and the handling of risks. The risks of innovation are of two quite different kinds: alongside the risks of something actually going wrong in the real world, is the emotional risk of being criticized or blamed, feeling foolish or embarrassed.

The interaction of these two types of risk (which for convenience I will label ‘subjective’ and ‘objective’) enables us to identify four different categories of risky situations, as follows:

Low Subjective/Low Objective

Feels low risk, and is in fact low risk, because the familiar methods are still appropriate – call it ROUTINE

High Subjective/Low Objective

Feels risky, because it is something I have not done before, but even if it turns out badly, the outcome is tolerable and affordable because it is a low risk experiment – call it EXPERIMENTAL

Feels safe, because it is familiar, but in fact is high risk, because the situation has changed and the old ways are no longer appropriate. Call it the OSTRICH position

High Subjective/High Objective

Feels risky, and is in fact high risk. It's a GAMBLE

The well managed business operates mainly in the lower half of the diagram below [see Figure 8.2], moving between the Routine and the Experimental (spiced, perhaps, with the occasional, affordable Gamble). It makes money from its Routine activities; it innovates and safeguards its future through the results of its Experimental work.

Figure 8.2

Similarly the individual manager will maintain a mix of routine and experimental activities, the routine providing a basis of productive output and the experimental pushing out the frontiers and new possibilities ...

By contrast, the business or individual who never experiments and continues to do things ‘the way we've always done it’ feels safe and comfortable but is in fact taking a big risk of being caught out by changing circumstances …

There then tends to be a panic reaction, an urgent need for drastic new action, without a bank of experimental learning and experimental skills to draw upon. The result is often a Gamble – a great leap forwards, into major new initiatives, untried and untested, with no groundwork of knowledge or experience.

Nolan's argument is an important one. It is that continuous improvement (which he calls ‘experimentation’) is an essential preparation for managing discontinuous change (the ‘gamble’) because:

![]() Continuous improvement reduces the need for ‘great leaps’ into the unknown.

Continuous improvement reduces the need for ‘great leaps’ into the unknown.

![]() Continuous improvement is a valuable way of developing the knowledge, skills and confidence necessary for innovation.

Continuous improvement is a valuable way of developing the knowledge, skills and confidence necessary for innovation.

Both points are crucial. As our personnel officer pointed out earlier, people find change uncomfortable and unsettling. Getting them to love change is probably unrealistic. However, developing an environment and a culture in which change is a way of life, where attempts to improve efficiency, effectiveness and responsiveness are welcomed, encouraged and supported, will go a long way to removing the fear of change and the unwillingness to experiment.

CASE STUDY

Talk to anyone in government service and they will complain about what has come to be known as ‘initiative fatigue’. This refers to the fact that, in the last decade, civil servants have been bombarded with changes to priorities, working practices, philosophies and the terms and conditions of employment. Many will state emphatically that ‘this isn't the organization I joined’.

The main trouble is that the current multiplication of change initiatives has followed generations of stability, even stagnation. Instead of implementing a long-term process of incremental change, civil servants are now being asked to respond to major discontinuous change, to which they are not accustomed and which is inconsistent with the expectations they brought when they joined.

The need for information

However, this does not change the fact that continuous improvement is essential to organizational survival. But if operations managers are to make continuous improvements which are genuine improvements, rather than irrelevant tweaks to the transformation process, they need to know:

![]() What are the priorities and main objectives of my organization currently?

What are the priorities and main objectives of my organization currently?

![]() How much do I really know about the wants and needs of internal and external customers?

How much do I really know about the wants and needs of internal and external customers?

![]() How satisfied are they with the outputs for which I am responsible?

How satisfied are they with the outputs for which I am responsible?

![]() What are my productivity and efficiency targets?

What are my productivity and efficiency targets?

![]() How likely are my current operating processes to achieve them?

How likely are my current operating processes to achieve them?

![]() What should be my priorities for improvement?

What should be my priorities for improvement?

![]() What authority do I currently have to implement changes?

What authority do I currently have to implement changes?

![]() If my authority is not consistent with the improvements I want to make, how can I increase it?

If my authority is not consistent with the improvements I want to make, how can I increase it?

![]() Alternatively, to whom should I submit proposals for improvement?

Alternatively, to whom should I submit proposals for improvement?

Ways of answering some of these questions are dealt with later in the chapter. Chapter 7 examines ways of monitoring efficiency, effectiveness and responsiveness and Chapter 10 will look at the issues of authority and authorization. So, for the moment, we shall leave the topic of why continuous improvement is necessary, in order to deal with the risks inherent in it.

RISKS OF CONTINUOUS IMPROVEMENT

‘Creative dissatisfaction’ – good or bad?

It is often argued that effective managers should be continuously subject to ‘creative dissatisfaction’. In other words, they should resist the temptation to leave things alone, just because they seem to be working all right. The argument is that most, if not all, operations and purposes are suboptimal in performance – they could be better, if only someone would actively seek improvements.

The opposite argument can be summarized in the American catch-phrase: ‘If it ain't bust, don't fix it’. The obvious implication of this is that seeking improvement where there is no obvious need for it stands a good chance of making things worse, not better.

CASE STUDY

Caius Petronius, a Roman centurion, wrote in AD 66:

We trained hard, but it seemed that every time we were beginning to form up into teams, we would be reorganized. I was to learn later in life that we tend to meet any new situation by re-organizing, and a wonderful method it can be for creating the illusion of progress while producing confusion, inefficiency and demoralization.

Confusion, inefficiency, demoralization

The case study quoted highlights three of the risks of any improvement initiative:

![]() Those involved in implementing it will be confused if the reasons for it are not communicated, explained and justified.

Those involved in implementing it will be confused if the reasons for it are not communicated, explained and justified.

![]() Change involves inefficiency, at least in the short term, as the new process or system is introduced, the shortfalls identified and the process debugged.

Change involves inefficiency, at least in the short term, as the new process or system is introduced, the shortfalls identified and the process debugged.

![]() People are often demoralized as they are forced to give up old operating methods with which they were familiar and which they took pride in making work, only to introduce new methods which prove inefficient and troublesome.

People are often demoralized as they are forced to give up old operating methods with which they were familiar and which they took pride in making work, only to introduce new methods which prove inefficient and troublesome.

All three of these risks apply to any change initiative, whether it is a matter of revolution (major change) or evolution (continuous improvement). But there are more:

We believe there are three, although each is significant enough to have several manifestations.

Irrelevance

The first, quite simply, is irrelevance. It was pointed out earlier that any continuous improvement process can only be justified in terms of its contribution to one of the following:

![]() increased customer satisfaction

increased customer satisfaction

![]() the achievement of corporate goals

the achievement of corporate goals

![]() cost reduction

cost reduction

![]() efficiency improvement

efficiency improvement

![]() the elimination of unproductive work

the elimination of unproductive work

![]() the reduction or elimination of waste

the reduction or elimination of waste

![]() increased job satisfaction.

increased job satisfaction.

CASE STUDY

A team of overseas observers was invited to watch an artillery demonstration by a British Army gun crew. As the crew took up its positions, one of the observers asked: ‘What is the purpose of that soldier standing to attention over there?’

His host replied: ‘He's there to hold the horses.’

The battalion concerned had been mechanized for over fifty years.

Arguably, removal of the soldier would have reduced costs, improved efficiency, eliminated unproductive work and increased job satisfaction by allowing him to transfer to more meaningful work. His removal would have been a classic example of continuous improvement, responding to technological change.

The next case study exemplifies the opposite – ‘continuous improvement’ which makes no contribution to anything, in fact, just the reverse!

A local government department in the West Midlands has attempted to improve internal communications by the introduction of electronic mail. This has incurred significant development and implementation costs. At the same time, the department has dispensed with management briefings, on the basis that these would be a duplication of effort.

In fact, staff now complain that they have no idea what is going on. In some cases, this is because senior management fail to put strategic decisions onto electronic mail. In other cases, it is because staff fail to access information which is on the system.

QUESTION

How well does this initiative achieve the objectives for continuous improvement we set out just now?

Briefly, we would suggest that the results of the initiative are:

![]() reduced customer satisfaction, in so far as the staff feel they are told less than before

reduced customer satisfaction, in so far as the staff feel they are told less than before

![]() as an attempt to achieve the corporate goal of improved internal communication, it has failed

as an attempt to achieve the corporate goal of improved internal communication, it has failed

![]() the cost of developing and implementing the system was probably higher than that of regular management briefings

the cost of developing and implementing the system was probably higher than that of regular management briefings

![]() efficiency has deteriorated – staff know less

efficiency has deteriorated – staff know less

![]() the work involved in developing and implementing the system has been unproductive

the work involved in developing and implementing the system has been unproductive

![]() the effect of up-dating the information on the system is largely wasted, because staff do not access it

the effect of up-dating the information on the system is largely wasted, because staff do not access it

![]() staff are dissatisfied.

staff are dissatisfied.

Overall, not a success!

Overambition

Our second risk inherent in continuous improvement is that of overambition or, put differently, it is the risk of assuming that you, as the operations manager, have access to the resources necessary to bring about the improvement you have identified.

Resources take many forms. Traditionally, they have been categorized as ‘the four Ms’:

![]() manpower

manpower

![]() money

money

![]() machinery

machinery

![]() motivation

motivation

although the first is now politically incorrect!

Nevertheless, this provides a useful breakdown. It also raises important questions for the operations manager in the implementation of continuous improvement:

![]() Do you have enough staff to maintain the required level of outputs, whilst undergoing the disruption of changing processes?

Do you have enough staff to maintain the required level of outputs, whilst undergoing the disruption of changing processes?

![]() Do they have the skills and attitudes necessary to seek and implement improvement?

Do they have the skills and attitudes necessary to seek and implement improvement?

![]() Is there any space in your budgets?

Is there any space in your budgets?

![]() What additional capital items can you afford?

What additional capital items can you afford?

![]() What freedom do you have to change revenue expenditure?

What freedom do you have to change revenue expenditure?

![]() How flexible is the equipment you currently use?

How flexible is the equipment you currently use?

![]() What changes to its usage are you entitled to make?

What changes to its usage are you entitled to make?

![]() What can you do about out-of-date or worn-out machinery?

What can you do about out-of-date or worn-out machinery?

![]() Will attempts at improvement be welcomed or seen as a threat?

Will attempts at improvement be welcomed or seen as a threat?

![]() Do your staff want to be involved in improvement – or do they see it as a threat?

Do your staff want to be involved in improvement – or do they see it as a threat?

![]() Are you in favour of continuous improvement?

Are you in favour of continuous improvement?

![]() Or opposed to it?

Or opposed to it?

Internal disruption

Our third risk is implied in what we have already said about meeting the needs of internal customers and operations management as a horizontal process or seamless web. It is the risk of internal disruption.

Coutts Development Consulting has recently introduced a new paperwork system for administrating its freelance consultants. The system requires consultants to use Coutts’ own forms for claiming fees and expenses. Whilst not a major inconvenience, this is contrary to freelance consultants’ normal method of raising their own invoices.

You may feel that causing aggravation to suppliers is not of great significance. After all, if you are paying them, they should do as they are told and be grateful.

QUESTION

What are the dangers of this attitude?

There are three dangers. First, in situations like this, customers are dependent on suppliers. It is dangerous to antagonize them to the point where you risk losing their support. Secondly, and returning to a point we made in Chapter 4, the consultants are customers too. Working on a freelance basis, they have the freedom to work for other clients. Finally, is the system efficient? It may be efficient for Coutts, but it certainly is not for the consultants – particularly when it comes to raising income tax returns! So, in terms of overall efficiency, is this a good idea?

Let us widen the discussion. If, as an operations manager, I or my team invent a way of improving a process, thereby improving efficiency and reducing costs in our section, what should I do if that improvement makes my customer's life more difficult?

The philosophy of total quality management would respond that customer satisfaction is the primary consideration. So internal efficiency and cost reduction are less important than meeting customer needs. In the context of the external customer, this is almost certainly true. But, when we consider internal customers, it is important to remember that we all work for the same organization. By extension, therefore, decisions about continuous improvement should be taken with reference to the organization's strategic aims and objectives or, in other words: what's best for the business as a whole?

So, how do we reconcile the different objectives we set out earlier for continuous improvement? That is part of the theme of the next section.

THE PROCESS OF CONTINUOUS IMPROVEMENT

Assessing the need

As we have already explained, the first stage of continuous improvement must be to work out whether there is any point in it, or in more detail:

![]() Is any improvement necessary?

Is any improvement necessary?

![]() How much would improvement contribute?

How much would improvement contribute?

![]() What cost is justifiable?

What cost is justifiable?

The answers to these questions are partly qualitative, partly quantitative.

Is any improvement necessary?

Few operations (if any) are perfect. All managers and all staff are fully capable of pointing out frustrations, stupidities, duplications, irrelevancies and waste. So, there is always room for improvement. Or is there? At this point, we would like to publish a couple of health warnings.

The first is a logical development of our quotation from Caius Petronius earlier in this chapter: all change leads to short-term inefficiency. As a result, it is important to recognize and quantify the short-term impact of change, in order to establish whether the short-term disruption is worthwhile and, secondly, to identify what action will be necessary in terms of, for example, staff consultation, training, replacement or additional equipment.

The second health warning is implicit in the advice ‘if it ain't bust, don't fix it’ quoted earlier. Faced with a problem, managers always have the choice to implement remedial action or to do nothing. Doing nothing is neither abdication nor admission of failure, provided that the decision has been taken deliberately and after consideration. There will be situations where the effort and resources needed to resolve the problem are more costly than the loss of output or quality which results from maintaining current operational processes.

How much would improvement contribute?

Continuous improvement may take the form of:

![]() eliminating duplication. For example, both the accounts department and line managers keeping records of expenditure.

eliminating duplication. For example, both the accounts department and line managers keeping records of expenditure.

![]() eliminating redundant steps. For example, repacking raw materials into smaller quantities if the process could be redesigned to accommodate the supplier's quantities, or if the supplier can deliver in smaller quantities.

eliminating redundant steps. For example, repacking raw materials into smaller quantities if the process could be redesigned to accommodate the supplier's quantities, or if the supplier can deliver in smaller quantities.

![]() smoothing the process. For example, by reducing the number of times inputs or outputs need to be handed on from one operation to another.

smoothing the process. For example, by reducing the number of times inputs or outputs need to be handed on from one operation to another.

![]() improving the layout. For example, by reducing the distances between sequential activities.

improving the layout. For example, by reducing the distances between sequential activities.

![]() processing in parallel. For example, by using network analysis, as we described in Chapter 3, in order to identify operational processes which could take place at the same time, thus reducing total duration.

processing in parallel. For example, by using network analysis, as we described in Chapter 3, in order to identify operational processes which could take place at the same time, thus reducing total duration.

![]() making the process more automated or introducing more sophisticated equipment. This need not be costly. A gas appliance installer reduced installation times by an average of 30 per cent by providing its engineers with plier wrenches, which are quicker to adjust than the adjustable spanners they had used previously.

making the process more automated or introducing more sophisticated equipment. This need not be costly. A gas appliance installer reduced installation times by an average of 30 per cent by providing its engineers with plier wrenches, which are quicker to adjust than the adjustable spanners they had used previously.

Any of these improvements would appear superficially desirable. However, it is important to ask:

![]() What are the nature and scale of the resulting benefits?

What are the nature and scale of the resulting benefits?

![]() Does the improvement bring drawbacks of its own? For example, if you discontinue your own expenditure records, does the accounts department take so long to publish its own that it will be too late to take remedial action when needed?

Does the improvement bring drawbacks of its own? For example, if you discontinue your own expenditure records, does the accounts department take so long to publish its own that it will be too late to take remedial action when needed?

![]() What will be the impact on the next activity or operation in the chain? For example, if you increase output by streamlining your operation, will this simply mean producing more inputs for the next operation than they can handle?

What will be the impact on the next activity or operation in the chain? For example, if you increase output by streamlining your operation, will this simply mean producing more inputs for the next operation than they can handle?

What cost is justifiable?

This question can be answered by calculating the short-term and long-term costs of the improvement in terms of money, time, effort and resources, and comparing them with the analysis of contribution and benefits we have just described.

Designing the improvement

Even if you have not involved your team in assessing the need for improvement – and it is normally good practice to involve them – it is essential that they should be at least consulted and ideally fully responsible for designing it.

The human resource strategy of Dudley Training and Enterprise Council states:

We recognize that the competence and experience of our staff entitle them to contribute to the planning process and to both understand and be involved in business decisions which affect them ... The TEC undertakes to delegate tactical decisions to those responsible for implementing them insofar as this is possible within the constraints of what is possible operationally.

The last part of this statement reflects the obvious fact that any organization operates within a framework of:

![]() budgetary constraints

budgetary constraints

![]() resource constraints

resource constraints

![]() corporate objectives and targets

corporate objectives and targets

![]() organizational values.

organizational values.

These are likely to set limits to the types and scope of improvement staff can realistically expect to implement. Staff need to know in advance from their manager or team leader what those limits are. Nothing is more demotivating than to be encouraged to seek improvements, only to be told at the end of the process that they are not affordable, or that the necessary resources cannot be made available, or that they are not in line with the business plan.

There are several ways of involving staff in process improvement. They may operate as:

![]() improvement project teams, brought together specially for that purpose

improvement project teams, brought together specially for that purpose

![]() cross-functional teams, with representatives from customer or supplier functions, or support or advisory functions like finance or marketing.

cross-functional teams, with representatives from customer or supplier functions, or support or advisory functions like finance or marketing.

![]() quality teams, in organizations which have already implemented TQM, where the team remains constant and meets regularly to take on different issues.

quality teams, in organizations which have already implemented TQM, where the team remains constant and meets regularly to take on different issues.

In all of these teams, effective teamworking and successful outcomes are dependent on a number of key factors.

Clear objectives

It is important that teams should know, and be regularly reminded of, the objectives they are seeking to achieve. Depending on the nature of the team, these may be set by management or it may be part of the team's responsibility to decide its current priority. The latter approach is more time-consuming, but has been shown to gain greater commitment, provided that the team is well led, disciplined and has the necessary problem-solving skills.

Meeting rules

Team members need a general idea of how frequently they will meet, at what time of day and how long the meeting will last. Individual meetings will benefit from an agenda circulated in advance, with details of any work to be done or papers to be read ahead of the meeting.

Meetings will need a chairperson, a secretary and an agreed set of principles by which to operate. These should include:

![]() how formal or informal the meetings are to be

how formal or informal the meetings are to be

![]() a recognition of everyone's right to be heard

a recognition of everyone's right to be heard

![]() the team's authority to, for example, co-opt others or require action

the team's authority to, for example, co-opt others or require action

![]() how decisions will be taken (unanimity, majority vote, whether the chairperson has a casting vote)

how decisions will be taken (unanimity, majority vote, whether the chairperson has a casting vote)

![]() the use of problem-solving and decision-making techniques such as brainstorming and the statistical evaluation of options.

the use of problem-solving and decision-making techniques such as brainstorming and the statistical evaluation of options.

Allocating action

Improvement project teams normally operate to a fixed schedule and disperse when the project has been completed. To achieve deadlines, it is normal for these teams to allocate follow-up action to individual members between meetings.

Quality teams are permanent. Consequently it may be too time-consuming to expect follow-up action from individuals, although this does sometimes happen.

Where teams do allocate action to individuals, it is important to ensure that the workload is shared fairly between members and that there is a general recognition that the completion of allocated action is compulsory, not optional.

Teamworking

By definition, improvement teams need to be creative. It is a responsibility of both the team leader and the members to:

![]() encourage and support creativity

encourage and support creativity

![]() listen to and build on others’ ideas

listen to and build on others’ ideas

![]() allow for differences in views

allow for differences in views

![]() reserve judgement

reserve judgement

![]() avoid personal criticism.

avoid personal criticism.

Further aspects of teamworking include reliable attendance, time-keeping, the completion of allocated actions and a willingness to contribute.

Process and progress reviews

It is advisable for teams regularly to set time aside to review both how successfully they are working together and the progress they are making.

Process reviews should cover:

![]() levels and standards of individual contributions

levels and standards of individual contributions

![]() interpersonal relationships

interpersonal relationships

![]() team co-operation.

team co-operation.

Progress reviews should cover:

![]() achievements against milestones and deadlines

achievements against milestones and deadlines

![]() relevance of action and success to date

relevance of action and success to date

![]() progress towards final objectives.

progress towards final objectives.

Implementing the improvement

Depending on the nature of the team, this may or may not be part of their responsibility. Ideally, though, it should be, for two reasons:

![]() Team members have the best understanding of the decisions they have taken and the intentions behind them.

Team members have the best understanding of the decisions they have taken and the intentions behind them.

![]() It is a source of considerable personal satisfaction to put in place an improvement you have designed – and see it work.

It is a source of considerable personal satisfaction to put in place an improvement you have designed – and see it work.

It is rare, though, for implementation to be possible totally without support from others.

Project and cross-functional teams are likely to be dependent on other teams and colleagues for implementation of at least part of the improvement. To ensure co-operation and effective implementation it is important to:

![]() communicate at the start the reasons for and objectives of the project, to gain commitment

communicate at the start the reasons for and objectives of the project, to gain commitment

![]() issue regular up-dates on progress

issue regular up-dates on progress

![]() consult regularly on issues which will impact on others

consult regularly on issues which will impact on others

![]() give clear guidance on implementation

give clear guidance on implementation

![]() monitor and supervise.

monitor and supervise.

CASE STUDY

Malcolm Field, then the Managing Director of W. H. Smith, commented to the Company Training Manager: ‘Management training costs me £3 million a year. What exactly am I getting for my money?’

The management team, after recovering from the shock, worked as a project team to find a way of quantifying the outcomes from management training. The resulting solution was a sophisticated form of measured performance assessment, carried out both before and after training and the measures compared.

Unfortunately, the project team failed to consult either its customers or its trainers. As a result, the customers neither understood nor supported the initiative and the trainers were very unenthusiastic.

Quality teams will normally require the support of their team leader or manager when it comes to implementing improvement. As we have pointed out, improvement brings short-term disruption and normally requires resources. Even in these days of empowerment – a theme to which we shall return in Chapter 10 – it is unusual for quality teams to have the authority to allow even a temporary drop in output, quality or efficiency, or to acquire the additional resources necessary.

Monitoring the improvement

The final stage in the continuous improvement process is to monitor the results arising from it. However, this should not be seen as an add-on, to be handled when all the other stages have been completed. Instead, monitoring systems should be a factor for consideration at the design stage and should continue to be a driving force throughout the rest of the process.

Monitoring in its broader applications was covered in Chapter 7. Here, I shall simply make some brief comments related to improvement monitoring. The first will already be familiar, since it relates to the need for quantified measures.

As Lord Kelvin said: ‘If you cannot measure that of which you speak, and express it as a number, your knowledge is meagre and unsatisfactory.’ This does not mean limiting the things you monitor to those you can count – units produced, machine utilization, volume of waste, for example. These are important, but only half the story. In addition, it is necessary to measure improvement in terms which do not lend themselves so readily to numbers – customer satisfaction, for example, or staff morale. However, as explained in Chapter 2, it is possible to quantify such factors by developing conversion charts which translate qualitative factors into quantities – although the process is slightly arbitrary.

Quantification is essential because of our next point. Improvement monitoring is a comparative process. It involves comparing the results actually achieved with:

![]() the objectives for the project

the objectives for the project

![]() historical results and, sometimes,

historical results and, sometimes,

![]() external or internal benchmarks, to identify whether there is further need or scope for improvement.

external or internal benchmarks, to identify whether there is further need or scope for improvement.

Of course, numbers offer the only satisfactory way of making comparisons.

Which brings us to our final point about monitoring improvement. Continuous improvement, by definition, is a never-ending process. At the same time, performance monitoring of any kind is only worthwhile if it leads to remedial action where this is necessary.

The consequent danger is that so many improvement initiatives are going on at the same time, or following each other in such quick succession, that it becomes impossible to identify the source of the results you are monitoring. After each initiative it is better to let each change settle long enough to get a clear picture of the improvement resulting from it. Otherwise, you may know that something has worked, but you will have little idea of what it was.

IMPLICATIONS OF CONTINUOUS IMPROVEMENT

Continuous improvement is a little like dropping a pebble into a pond. As the ripples spread, they shake the reeds, disturb the ducks, splash the paddler on the other side and, possibly, capsize a little child's toy boat!

The theme of this section is the need to consider carefully the impact of continuous improvement on the various stakeholders of an organization. Such impact will vary in importance – sometimes it will be major, sometimes minor. It may be planned and intentional, or unintended and unexpected. It may be positive – or negative. Careful analysis is necessary to ensure that all impact is intentional and beneficial.

An organization's stakeholders can be defined as: all those parties to whom an organization owes a responsibility or duty of care. Or even, more cynically: all individuals and groups which can exert any influence over the organization.

The following list is representative:

Contractual stakeholders

![]() shareholders

shareholders

![]() employees/voluntary workers

employees/voluntary workers

![]() customers/clients (both internal and external)

customers/clients (both internal and external)

![]() members (in the case, for example, of a club, professional institute or motoring organization)

members (in the case, for example, of a club, professional institute or motoring organization)

![]() suppliers

suppliers

![]() lenders.

lenders.

Other stakeholders

![]() government

government

![]() regulators

regulators

![]() electorate

electorate

![]() general public

general public

![]() pressure groups

pressure groups

![]() media.

media.

Your organization may define its stakeholders more narrowly. Indeed, some older management texts limit stakeholders to the owners of the business, specifically the shareholders. However, more recent management authors adopt the wider definition, which also has greater relevance for public and not-for-profit organizations.

Earlier in this chapter, the first stage in continuous improvement was described as being the assessment of need, and one element of that stage as the identification of benefits and drawbacks. The following case study shows how apparent benefits may be balanced by drawbacks.

CASE STUDY

Didcot Power Station ceased to bring in coal by train and transferred to road haulage. This operational decision was taken to reduce costs.

However, the decision overlooked, or chose to ignore, the impact on the community and other road-users. Buildings and washing on lines were all covered in coal dust, whilst roads past the station were clogged with slow-moving lorries.

The result was a succession of expensive and disruptive protests, although the decision remained unchanged.

So what impact would continuous improvement initiatives have on stakeholders? Here are some examples, chosen at random:

![]() Increased efficiency leading to faster throughput may require extra or more frequent supplier deliveries.

Increased efficiency leading to faster throughput may require extra or more frequent supplier deliveries.

![]() Simpler order documentation may require staff in internal customer departments to be retrained.

Simpler order documentation may require staff in internal customer departments to be retrained.

![]() Improved output specifications may necessitate different components or raw materials from suppliers.

Improved output specifications may necessitate different components or raw materials from suppliers.

![]() A design consultancy may find its clients unable to respond quickly enough to draft copy or illustrations.

A design consultancy may find its clients unable to respond quickly enough to draft copy or illustrations.

![]() A utility company which increases its efficiency and sends out bills earlier may find that customers pay as before, resulting in more overdue accounts.

A utility company which increases its efficiency and sends out bills earlier may find that customers pay as before, resulting in more overdue accounts.

![]() Improved systems may be more efficient, but are inconsistent with supplier or customer systems.

Improved systems may be more efficient, but are inconsistent with supplier or customer systems.

![]() Improvements carried out for internal benefit may be unacceptable to external customers.

Improvements carried out for internal benefit may be unacceptable to external customers.

CASE STUDY

The hospitals in Oxford decided to increase revenue by charging outpatients and visitors for car parking. As a result, many now use the (free) staff car parks. In consequence, staff car parks are often full and it has been necessary to introduce vehicle clamping to reduce the problem.

In all of these examples, initiatives have turned out to lead to less improvement than intended, because of failure to foresee the full consequences.

There is not enough space here to explore fully all the possible implications of continuous improvement as it affects you. However, we can offer a summary in the form of a series of questions.

What are the implications of a continuous improvement initiative in terms of:

![]() systems compatibility?

systems compatibility?

![]() customer acceptance?

customer acceptance?

![]() supplier responsiveness?

supplier responsiveness?

![]() product or service compatibility?

product or service compatibility?

![]() workforce acceptance?

workforce acceptance?

![]() training needs?

training needs?

![]() recruitment or redundancy?

recruitment or redundancy?

![]() community acceptance?

community acceptance?

![]() media response?

media response?

![]() investor response?

investor response?

![]() component or raw material needs?

component or raw material needs?

![]() equipment needs?

equipment needs?

Some of these questions apply to operations at a macro level, others to operations at a micro level, yet others to both. At first sight, some improvement initiatives may seem so minor that their impact on stakeholders will be minimal. In such cases, it is worth remembering the ripples in the pond.

COMPETENCE SELF-ASSESSMENT

1Does your organization pay as much attention to continuous improvement as it should to ensure its survival? How about you personally?

2How much environmental change is your organization experiencing? And your operation?

3How much do you know about your organization's priorities, objectives and chosen markets?

4What authority do you have to implement continuous improvement? Whose agreement do you need?

5How could you create a climate where your staff would support continuous improvement?

6Who do you consult about continuous improvement? Your staff? Your boss? Internal customers? Internal suppliers? Anyone else?

7How do you assess the need for improvement? What else could you do?

8Does your organization use improvement teams? If so, how could they be made more effective?

9How do you monitor improvement? What more could you do?

10Who are your organization's and your own stakeholders? How could you improve the way you consider the impact of improvement on them?