9Managing change

In the last chapter, the need for a cautious approach to continuous improvement and the potential pitfalls inherent in the process were emphasized. In particular, I pointed out:

![]() the need to balance costs and benefits

the need to balance costs and benefits

![]() the dangers of excess enthusiasm

the dangers of excess enthusiasm

![]() the impact of employee resistance

the impact of employee resistance

![]() the possibility that product or service improvements may not be welcomed by the next customer in the value chain.

the possibility that product or service improvements may not be welcomed by the next customer in the value chain.

So, does that mean that the larger-scale operation of managing change is less fraught with those risks? Unfortunately, no. In fact, if continuous improvement demands careful handling, the need for care in managing revolutionary, rather than evolutionary, change is even greater.

‘I told you so‘, commented our personnel officer. ‘I said that people don't like change. It makes them feel uncomfortable. It's all very well to talk about the survival of the fittest – but how do you think the dinosaurs felt about that? Change means threat, however carefully you manage it. People are afraid they won't be able to cope, won't be able to adapt.’

‘Yes, but‘, broke in the marketing manager, ‘you can't just ignore the need for change. If we're not competitive, or fail to keep our products in line with customer requirements, or don't keep up with environmental change, then we're not going to survive. Business history is littered with dinosaurs. Think of the Sinclair C5 – that little three-wheeled electric car. Nobody wanted it – and it died. Or bespoke suits – high street tailors couldn't compete on price or delivery with the ready-made variety. How many tailors do you see these days outside Savile Row – and they compete in a different market! Or the old American gas-guzzler automobiles. They evolved too slowly to respond to change in the fuel market, so they lost out to European and Japanese cars. The message is right, you know – adapt or die.’

Our production manager felt trapped in the middle again. He could see the force of both arguments. He had experienced disruption when the factory had introduced new shift-work arrangements – and seen the resentment on the faces of his team. But he could also recognize the resultant cost savings and the need to increase output in line with customer demand. So who was right?

That question is answered in the remainder of this chapter. In it, I shall:

![]() present two approaches to problem-solving; the analytical or remedial on the one hand and the creative on the other. The first is more likely to identify the need for small-scale changes; the second to highlight opportunities for revolutionary improvement. Between them, they go some way to quantifying the size, scope and implications of change.

present two approaches to problem-solving; the analytical or remedial on the one hand and the creative on the other. The first is more likely to identify the need for small-scale changes; the second to highlight opportunities for revolutionary improvement. Between them, they go some way to quantifying the size, scope and implications of change.

![]() examine the organization pressures which are likely to promote change, and those likely to resist it. Taken together, those two sets of pressures will help you identify the actions necessary to bring about effective change. This process is called force-field analysis.

examine the organization pressures which are likely to promote change, and those likely to resist it. Taken together, those two sets of pressures will help you identify the actions necessary to bring about effective change. This process is called force-field analysis.

![]() deal with the human factors of change by exploring what makes people fearful of or threatened by change; and discussing what can be done to help staff, if not to love change, then at least to accept and feel ownership of it.

deal with the human factors of change by exploring what makes people fearful of or threatened by change; and discussing what can be done to help staff, if not to love change, then at least to accept and feel ownership of it.

APPROACHES TO PROBLEM-SOLVING

Effective problem-solving requires answers to the following ten questions:

![]() What is the current situation?

What is the current situation?

![]() What is wrong with it?

What is wrong with it?

![]() What has caused the problem?

What has caused the problem?

![]() What are its longer-term consequences?

What are its longer-term consequences?

![]() To whom is it important?

To whom is it important?

![]() How would things look if the problem were resolved?

How would things look if the problem were resolved?

![]() What are the alternative solutions?

What are the alternative solutions?

![]() How much would each cost?

How much would each cost?

![]() Which provides the best fit with the problem?

Which provides the best fit with the problem?

![]() How can it be implemented?

How can it be implemented?

These questions are all consistent with both the analytical and the creative approaches to which we have already referred.

The first, analytical, approach is characterized by the technique advanced by C. H. Kepner and B. B. Tregoe in their book The Rational Manager (McGraw-Hill, 1965). Kepner and Tregoe define a problem as ‘a deviation from the norm’. Analytical problem-solving emphasizes the use of quantitative measures to identify the nature, resulting cost and consequent seriousness of a problem, and to evaluate potential solutions. Developed in the 1950s and 1960s (a period of relative stability and predictability), the analytical approach is based on the assumption that there is ‘one best way’ of doing things and that problem-solving is a process of identifying what that one best way should be and removing any obstacles to achieving it.

The creative approach to problem-solving, by contrast, defines a problem as ‘the gap between where we are and where we want to be’. This definition, used by Vincent Nolan in Problem Solving (Sphere Books, 1987), is again typical of its period, in that it emphasizes a search for the ideal, thinking the unthinkable, the idea that perfection is just around the corner. Unlike the analytical approach, which acknowledges and acts within given limitations – of time, resources and budget, for example – creative problem-solving encourages us to disregard limitations and ‘reach for the stars’.

Your reactions to these two alternative approaches to problem-solving will have been indicative of the organizational environment in which you operate. If your organization is risk-averse, discourages experimentation and either longs for or genuinely operates within a stable environment, you will probably have felt much more sympathy with the analytical approach. Even if your organization is tentative in its outlook and you feel frustrated by it, you may still feel that analytical problem-solving is the only safe route for you to follow.

Alternatively, if creative problem-solving was ringing bells for you, that probably means that your organization is facing major environmental challenges and has decided to risk some large-scale leaps into the unknown.

In either case, it is worth giving some serious thought to the ten questions we raised earlier.

What is the current situation?

In the language of analytical problem-solving, this may be a deviation from the norm in the shape of a difference between a historical pattern (identified by the kind of monitoring described in Chapter 7 of this book) and current performance.

Mentmore, the plastics-moulding company best known for Platignum pens but now a major supplier of components to Electrolux, Black and Decker and BT, established that it had suffered an unacceptable fall in profits which threatened shareholder returns. Further research revealed that this had resulted from entering into a single, but large, contract with a key customer which had been incorrectly costed. The question was: what to do about it?

Or, in the language of creative problem-solving, the current situation may be a gap between where we are and where we want to be in the shape of an inability to perform to the standards now expected by our customers, or imposed on us by our competition.

CASE STUDY

As the name suggests, Radio Rentals entered the market as a renter of home entertainment equipment which, at the time, was both too unreliable and too expensive for customers to buy. As the equipment became more reliable and retail prices fell, Radio Rentals found itself facing intense competition from shops offering similar equipment for sale. The company took the decision to diversify into both equipment sales and the rental of more complex items, dependent on more frequent maintenance (such as the early generations of home computers and domestic freezers).

What is wrong with it?

In both these examples, the answer to this question is, with hindsight, obvious. Mentmore had lost profit, Radio Rentals was losing market share. In other situations, the answer is less obvious:

![]() An increase in staff turnover may result in higher recruitment costs and reduced efficiency.

An increase in staff turnover may result in higher recruitment costs and reduced efficiency.

![]() An increase in machine downtime may result in lower output and higher unit costs.

An increase in machine downtime may result in lower output and higher unit costs.

![]() A lack of sales staff may result in lost sales or reduced customer satisfaction (all examples of variations from the norm).

A lack of sales staff may result in lost sales or reduced customer satisfaction (all examples of variations from the norm).

![]() ‘All anyone does around here is complain’ is a statement which suggests low productivity and poor morale.

‘All anyone does around here is complain’ is a statement which suggests low productivity and poor morale.

![]() ‘We're the retailer of last resort’ suggests unreliable turnover and profit, and a poor reputation with customers.

‘We're the retailer of last resort’ suggests unreliable turnover and profit, and a poor reputation with customers.

![]() ‘All this organization does is copy other people's ideas’ suggests not only a lack of creativity, but also a failure to predict and plan for the future (all examples of gaps between where we are and where we want to be).

‘All this organization does is copy other people's ideas’ suggests not only a lack of creativity, but also a failure to predict and plan for the future (all examples of gaps between where we are and where we want to be).

It is at this point that analytical and creative problem-solving start to diverge. The analytical approach emphasizes the quantification of what is wrong with the current situation – lost output, reduced productivity, lost sales, and so on. The creative approach, on the other hand, is content to recognize that the current situation does not meet the wishes of the problem-owner and saves quantification until a later stage. With either approach, however, it will be necessary to compare the cost of alternative solutions with the cost of leaving the situation as it is, as we shall see later.

What has caused the problem?

This question is central to analytical problem-solving. A deviation from the norm means, by definition, that things were running smoothly, then something happened to disrupt them. An analysis of when the problem occurs, how often, under what circumstances and where, enables the problem to be pinpointed. Possible causes can then be identified and each one assessed to establish whether the effect resulting from it is consistent with the condition arising from the problem.

This analysis is far less important to the creative approach. In fact, those in favour of creative problem-solving would argue that defining the problem too narrowly automatically closes the door on solutions which, although they may not address the problem directly, offer wider improvements. Nevertheless, it is still helpful to find out why this problem is suddenly a priority for the problem-owner, as part of the background to it.

CASE STUDY

The owner-manager of a small garage in West London asked for help in solving a problem of incapable staff. An analytical approach identified that this was not a deviation from the norm. The staff had never been capable. Further questioning using the creative approach identified that this was an issue because the owner was considering retirement and wanted to hand over the business to someone who could run it at a profit, so that he could continue to draw dividends.

What are its longer-term consequences?

This question is helpful in determining:

![]() the urgency of the need for a solution

the urgency of the need for a solution

![]() whether the problem warrants a solution now or at all.

whether the problem warrants a solution now or at all.

We can exemplify both points by considering the same hypothetical situation.

CASE STUDY

Imagine a light-engineering company manufacturing mild steel pressings. By monitoring the volume of waste product, it has identified a deviation from the norm in the shape of a growing number of rejects caused by the gradual wearing out of its machines. However, the company has also recognized that it has enough machine capacity to meet demand for the next five years, using quality control techniques to ensure customer satisfaction and assuming that the reject rate continues to increase in line with the current trends. It has also calculated that the cost of replacing its old machines would be significantly higher than the cost of lost production and tighter quality control over those five years.

Using creative problem-solving, the company has also established that, within five years, it would be well advised to get out of the metal pressings market, in view of declining demand and growing overseas competition. Where it wants to be is in the manufacture of electronic components, requiring totally different machinery.

In this example, it is clear that the company, whilst certainly having a problem, would be better off living with it for five years, at which point the problem will have changed beyond recognition.

We can draw a number of conclusions from this:

![]() Doing nothing can be a valid response to some problems.

Doing nothing can be a valid response to some problems.

![]() Such a decision can only be justified by a careful analysis of longer-term costs and consequences.

Such a decision can only be justified by a careful analysis of longer-term costs and consequences.

![]() Short-term solutions must take account of longer-term strategic direction.

Short-term solutions must take account of longer-term strategic direction.

![]() Solutions to today's problems may well not be relevant to tomorrow's problems.

Solutions to today's problems may well not be relevant to tomorrow's problems.

Nevertheless, it would be dangerous to imply too much from these conclusions. A temptation to be avoided is that of ignoring small-scale tactical action to resolve a problem, in favour of waiting for a larger strategic initiative to mop it up along with several others. There are three reasons for avoiding this temptation:

![]() the potential cost and inconvenience of living with the problem

the potential cost and inconvenience of living with the problem

![]() the drawback, which was described in Chapter 8, that operational teams at the ‘sharp end’ of the business gain no practice in implementing change

the drawback, which was described in Chapter 8, that operational teams at the ‘sharp end’ of the business gain no practice in implementing change

![]() the fact that reliance on strategic change to bring about improvement means that change is always imposed on people from outside, rather than being a home-grown process.

the fact that reliance on strategic change to bring about improvement means that change is always imposed on people from outside, rather than being a home-grown process.

It is for these reasons that the decision to tackle a problem or not should be based on an analysis of the consequences and on objective consideration of the outcomes of a strategic initiative, rather than wishful thinking.

To whom is it important?

This question relates to three separate categories of people:

![]() the problem-owner

the problem-owner

![]() the authority-holder

the authority-holder

![]() the solution-implementer.

the solution-implementer.

The problem-owner

This is the person on whom the problem has the greatest impact, the one who is sufficiently dissatisfied with the present situation to be motivated to solve it.

Vincent Nolan recommends finding answers to five questions about that individual:

![]() Is the person willing to do something about it or just looking for sympathy?

Is the person willing to do something about it or just looking for sympathy?

![]() Is that person prepared to make a personal effort or are they expecting someone else to solve the problem for them?

Is that person prepared to make a personal effort or are they expecting someone else to solve the problem for them?

![]() What is the problem-owner's power to act? What action are they empowered to take? What resources do they have available? What are the limits to the solutions they can implement?

What is the problem-owner's power to act? What action are they empowered to take? What resources do they have available? What are the limits to the solutions they can implement?

![]() Is the problem-owner seeking a solution or proof that none exists? (with a consequent wish for sympathy, as above).

Is the problem-owner seeking a solution or proof that none exists? (with a consequent wish for sympathy, as above).

The authority-holder

This is the person with the authority and access to resources necessary for solving the problem. As we have already mentioned, the process of delegated decision-making and empowerment are making it increasingly likely that the problem-owner and the authority-holder will be one and the same person. However, two words of caution are necessary:

![]() Empowerment is a textbook philosophy. Whilst most organizations nowadays are committed to the idea of delegated authority, this is not always translated into action which makes it possible. The following case study provides a simple explanation.

Empowerment is a textbook philosophy. Whilst most organizations nowadays are committed to the idea of delegated authority, this is not always translated into action which makes it possible. The following case study provides a simple explanation.

CASE STUDY

The Premises Supervisor of Wolverhampton Training Centre is responsible for reception, catering and maintenance. The caretaker on site, who looks after minor repairs and also organizes tea, coffee and sandwiches for delegates, reports to her. However, she cannot authorize petty cash expenditure over £25. As a result, the purchase of materials for repairs or of most replacement equipment (a couple of flipchart pads, for example) has to be referred to higher management for approval or a formal order.

It is therefore not unusual for a problem-owner to know exactly what needs to be done to solve the problem, but to be prevented from implementing the solution because the problem is causing no inconvenience to the person who can authorize the resources or expenditure needed to resolve it, who therefore does not see it as worth tackling.

![]() The ‘jobsworth’ response. I have used this title to describe a response to problems which was historically common in role cultures (see Chapter 4). It is the idea that problems are ‘their’ fault and that it is up to ‘them’ to solve them. ‘They’ may be the management or another team or department. The problem-owner is demonstrating some of the behaviours we described earlier:

The ‘jobsworth’ response. I have used this title to describe a response to problems which was historically common in role cultures (see Chapter 4). It is the idea that problems are ‘their’ fault and that it is up to ‘them’ to solve them. ‘They’ may be the management or another team or department. The problem-owner is demonstrating some of the behaviours we described earlier:

![]() looking for sympathy rather than action

looking for sympathy rather than action

![]() expecting someone else to solve the problem

expecting someone else to solve the problem

![]() subconsciously hoping for confirmation that a solution is impossible, thereby expecting sympathy and the opportunity to blame someone else.

subconsciously hoping for confirmation that a solution is impossible, thereby expecting sympathy and the opportunity to blame someone else.

We shall examine the question of what an ideal solution would look like a little later in this chapter. For the moment, it is worth stressing that the best antidote to the ‘jobsworth’ response is for the problem-owner to ask: NOT ‘What should they do to solve this problem?’ BUT RATHER ‘What can I do to solve it?’

CASE STUDY

Relate (formerly the Marriage Guidance Council) offers a valuable piece of advice to couples who are struggling with incompatible expectations, attitudes or behaviour in their relationships. The advice is to recognize that one partner has neither the power nor the right to change the other. Instead, both partners should ask themselves: ‘What can I change about myself which will resolve this problem?’

The solution-implementer

This is the person, or group of people, who will be responsible for taking the action to resolve the problem. The following recommendations should come as no surprise:

![]() Implementers should know the background to the problem, why it is a problem and what the solution is intended to achieve.

Implementers should know the background to the problem, why it is a problem and what the solution is intended to achieve.

![]() The more they are involved in designing the solution, the more committed they will be.

The more they are involved in designing the solution, the more committed they will be.

![]() Implementers need access to suitable resources.

Implementers need access to suitable resources.

CASE STUDY

A food processing plant in Liverpool continued to use machines first introduced twenty years previously. The workforce was asked to suggest ways of improving morale and productivity. One group pointed to the machines they operated and explained forcefully that the only way they would keep them working was by using clothes-pegs, odd bolts, lengths of timber and cardboard boxes, which the management would see if only they bothered to come down from their ivory towers and look.

How would this look if the problem were resolved?

The answer to this question varies according to the problem-solving approach you are following. The analytical answer is straightforward: things have been restored to the status quo.

The creative answer requires considerably more effort. Vincent Nolan explains: ‘To articulate the need in a really powerful way so that it becomes a magnet for new ideas and a real stimulus to our creative abilities, we have to re-learn how to wish for the impossible’.

Wishing for the impossible is not a normal management process! Nevertheless, a number of techniques exist to encourage the process:

![]() writing a ‘vision of the future’. This involves writing a fantasy description of the way things would look if your operation were successful beyond your wildest expectations.

writing a ‘vision of the future’. This involves writing a fantasy description of the way things would look if your operation were successful beyond your wildest expectations.

![]() wishing in picture form. A variation on the first technique, by which you imagine in visual form a perfect version of your operation and then analyse what makes it perfect.

wishing in picture form. A variation on the first technique, by which you imagine in visual form a perfect version of your operation and then analyse what makes it perfect.

![]() springboards. This involves using phrases like ‘I wish we could …‘, ‘It would be so much better if …‘, then recording the rest of the sentence and using it as a springboard to move on to more extravagant wishes.

springboards. This involves using phrases like ‘I wish we could …‘, ‘It would be so much better if …‘, then recording the rest of the sentence and using it as a springboard to move on to more extravagant wishes.

![]() backwards/forwards planning. This technique starts with the problem as defined, and assumes a solution has been found. It then looks for additional benefits which would arise from that solution. For example: the original problem is how to speed up the processing of customer payments. If customer payments were processed faster, this would improve cash flow. So the problem becomes: how to improve cash flow. The benefit of improved cash flow would be more money available for investment. So the problem now becomes: how to make more money available for investment.

backwards/forwards planning. This technique starts with the problem as defined, and assumes a solution has been found. It then looks for additional benefits which would arise from that solution. For example: the original problem is how to speed up the processing of customer payments. If customer payments were processed faster, this would improve cash flow. So the problem becomes: how to improve cash flow. The benefit of improved cash flow would be more money available for investment. So the problem now becomes: how to make more money available for investment.

Of course, this technique can be carried to ridiculous extremes, such as where the problem becomes: how to make this organization more successful.

However, it is helpful to advance backwards/forwards planning to the point where it reaches natural boundaries: the limits of an operation, for example, or of a manager's authority.

What are the alternative solutions?

This is where our two approaches to problem-solving converge again. Regardless of whether you have a specifically defined problem derived from the analytical approach, or a loose definition based on the creative approach, you are most likely to come up with an effective solution if you have generated an extensive menu to choose from.

Idea generation can employ a wide range of methods. For example:

![]() brainstorming

brainstorming

![]() lateral thinking

lateral thinking

![]() word association

word association

![]() visualizing

visualizing

![]() doodling.

doodling.

The essence of any of these is to deliberately cast off the restraints of past experience (‘we tried that before – it didn't work’), practicability (‘they'd never allow it’ or ‘we haven't the resources’) or even common sense (‘that's a daft idea’). Instead, the first stage of idea generation is to let your thoughts and your imagination roam freely, discarding nothing, no matter how impossible it may appear.

Some of these methods can be used by an individual. However, idea generation is most powerful when used by a group, so that people can build on others’ ideas, or use them as a springboard for their own.

The second stage of idea generation is to go back to the list of alternatives you have identified and weed out those which are not worth taking further. This may be because they are:

![]() illegal

illegal

![]() inconsistent with the organization's values

inconsistent with the organization's values

![]() dependent on resources or technology which the organization cannot obtain.

dependent on resources or technology which the organization cannot obtain.

It is important, though, not to discard ideas too soon. It may be possible to adapt or combine them to develop a further alternative which is free from the disadvantages of the original idea.

How much would each cost?

This question is, in fact, shorthand for a much longer series of questions. To answer it requires accurate analysis of the following:

![]() What physical resources (staff, equipment, space) will each solution require?

What physical resources (staff, equipment, space) will each solution require?

![]() How much will those resources cost?

How much will those resources cost?

![]() What expertise will each solution require?

What expertise will each solution require?

![]() Is it available in-house or will it need to be bought in?

Is it available in-house or will it need to be bought in?

![]() How much will that expertise cost?

How much will that expertise cost?

![]() How long will implementation take?

How long will implementation take?

![]() How much disruption will it involve?

How much disruption will it involve?

![]() What will the disruption cost in terms of lost output, customer inconvenience, staff resistance?

What will the disruption cost in terms of lost output, customer inconvenience, staff resistance?

![]() How much added value will each solution bring?

How much added value will each solution bring?

![]() How does that added value compare with the costs involved?

How does that added value compare with the costs involved?

These are not calculations that can be made on the back of an envelope. Instead, they may need to involve the use of cost-benefit analysis, discounted cash flow (DCF) and certainly attention to the impact on both staff and customers (whether internal or external). Two overriding factors are particularly important:

![]() the need to approach each analysis in an objective way, resisting the temptation to take an optimistic view of apparently favourable solutions, whilst assuming the worst of solutions which are less attractive at first sight

the need to approach each analysis in an objective way, resisting the temptation to take an optimistic view of apparently favourable solutions, whilst assuming the worst of solutions which are less attractive at first sight

![]() a recognition that any change initiative is likely to need more resources, take longer, involve more disruption and cost more than the planners anticipated.

a recognition that any change initiative is likely to need more resources, take longer, involve more disruption and cost more than the planners anticipated.

This apparently cynical comment is invariably borne out by experience.

CASE STUDY

The dream of a road-link to France has inspired people in Britain since the successful conclusion of the Napoleonic wars. In 1987 Eurotunnel went to the market for funding to undertake the Channel Tunnel. The amount sought proved woefully inadequate. Eurotunnel has experienced:

![]() disputes with contractors

disputes with contractors

![]() death of workers, attributed to poor safety regulations

death of workers, attributed to poor safety regulations

![]() changes of government

changes of government

![]() a fire in the tunnel

a fire in the tunnel

![]() major cash flow difficulties on the part of the rail operator.

major cash flow difficulties on the part of the rail operator.

We do not know how much risk analysis Eurotunnel carried out, to determine what might go wrong and what the consequences would be. All we can say is that the risk analysis was significantly more optimistic than hindsight shows it should have been.

Which provides the best fit with the problem?

This question is closely related to the last one and also needs to be rephrased in greater detail. It is really asking: which alternative solution deals with most of the problem at the least cost?

Of course, there are two sides to this more detailed question. On the one hand, do the problem-owner and the authority-holder prefer a cheap, quick and dirty solution which deals with the worst result of the problem? Or are they prepared to resource a more complex, sophisticated and costly solution which eliminates the problem entirely and adds value elsewhere at the same time?

Our two approaches to problem-solving reveal different preferences at this stage. Analytical problem-solving results in a solution which addresses the root cause of the problem, but has no interest in spin-off benefits. Creative problem-solving, by contrast, is likely to come up with a large-scale solution which overcomes the problem, adds value elsewhere, but may well involve significant resources, disruption and cost.

How the organization defines ‘best fit’ will be a result of its culture and the environmental factors impacting on it. Using the descriptions from Chapter 4, a power culture will pour an unlimited quantity of resources into resolving a problem which senior managers are convinced is important. A task culture is committed to ideas, expertise and experimentation. It will favour interesting solutions which may lead to exciting consequences elsewhere (good or bad). A role culture is subject to rules, procedures and hierarchical controls. Solutions will be expected to resolve the problem, be cost-effective and not to create waves elsewhere in the organization.

Environmental fit relates primarily to the speed and discontinuity of external change. As we mentioned earlier, analytical problem-solving stems from a stable and relatively predictable era. In consequence, it results in solutions which are limited and focused. If your organization operates in a relatively stable environment – and does not envisage dramatic change – then limited, cost-effective solutions without implications are likely to be favoured. On the other hand, if your organization identifies with the writings of Tom Peters, John Naisbitt, Alvin Toffler or Charles Handy, and is seeing itself as subject to discontinuous economic, social, technological or competitive change, it is likely to be willing to support solutions which are far-reaching in scope and costly to implement.

Following the steps we have described, it is reasonably straightforward to solve problems in an organization whose culture is consistent with its environment. But what should an operations manager do in an organization where the culture and the environment are not in line with each other? There are two possibilities, neither of which is easy.

The first is to create a local culture which is genuinely consistent with the environment. This will result in an ongoing confrontation with the style, controls and procedures which apply in the rest of the organization, but will at least make your operation responsive to the environment which, ultimately, governs it.

The second is to undertake an education and transformation programme throughout the organization, in order to bring it in line with the environment. The success of this initiative will depend on the extent to which other managers and other departments have recognized the inconsistency between the culture of the organization and the reality of the organization.

How can it be implemented?

We gave most of the answers to this question in Chapter 8. It involves:

![]() flow-charting the activities involved

flow-charting the activities involved

![]() calculating resources, costs and time-scales

calculating resources, costs and time-scales

![]() identifying and allocating responsibilities

identifying and allocating responsibilities

![]() communicating reasons, standards and deadlines

communicating reasons, standards and deadlines

![]() designing and implementing a monitoring and control system

designing and implementing a monitoring and control system

![]() carrying out a risk analysis

carrying out a risk analysis

![]() deciding ‘what do we do if this or that goes wrong?’

deciding ‘what do we do if this or that goes wrong?’

In the previous step, you identified the best-fit solution. However, it is important to recognize that, even at this final stage, it may be necessary to revise your previous choice. This is the last opportunity to ask some searching questions:

![]() Is this really possible in the time?

Is this really possible in the time?

![]() Are those costs realistic?

Are those costs realistic?

![]() Are these people really capable of delivering the results we need?

Are these people really capable of delivering the results we need?

![]() Can we afford the risk?

Can we afford the risk?

![]() Can we afford the consequences if it does go wrong?

Can we afford the consequences if it does go wrong?

The answers to these questions may result in the choice of an alternative solution, or a change to:

![]() time-scale

time-scale

![]() resources

resources

![]() people

people

![]() contingency plans.

contingency plans.

They may even result in a decision that it is preferable to remain with the current situation, because all of the alternatives are too risky.

Figure 9.1Approaches to problem-solving

Figure 9.1 highlights the differences and similarities between our two approaches to problem-solving at successive stages of the process.

FORCE-FIELD ANALYSIS

The concept of force-field analysis

The concept of force-field analysis was developed in the 1930s by management scientist Kurt Lewin, in an attempt to explain why organizations found the successful implementation of change so difficult. Lewin started from the premise that the purpose of change is to bring about improvement. In theory, therefore, change should be welcome. But his research showed – and our own experience confirms – that change is often resisted.

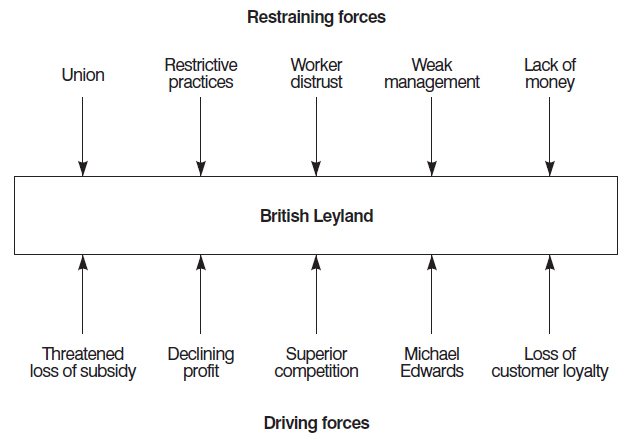

Lewin suggested that this is because there are two sets of opposing forces at work in an organization – driving forces and restraining forces. He argued that change fails to take place when the two sets of forces are equally balanced. His diagram representing force-field analysis is shown in Figure 9.2.

Figure 9.2Force-field analysis

Driving forces are those which promote change. Restraining forces are those which maintain the status quo. While these two sets of forces remain equal and opposite, the situation remains in balance; no change takes place. A practical example will illustrate this effect.

CASE STUDY

When Sir Michael Edwardes took over as boss of British Leyland, the company was losing sales and market share, becoming increasingly uncompetitive and risked going out of business. He identified an obvious and urgent need for change if the company was to survive. However, it took several years of effort and struggle to bring those changes about. The driving forces for change included:

![]() threat of withdrawal of government subsidy if improvements did not take place

threat of withdrawal of government subsidy if improvements did not take place

![]() declining profitability

declining profitability

![]() superior competitor products

superior competitor products

![]() Michael Edwardes's own dynamism

Michael Edwardes's own dynamism

![]() loss of customer loyalty.

loss of customer loyalty.

The restraining forces, however, were equally real and powerful:

![]() an excessively strong union

an excessively strong union

![]() restrictive practices

restrictive practices

![]() deep worker distrust of management

deep worker distrust of management

![]() weak and often incompetent management

weak and often incompetent management

![]() lack of money for investment.

lack of money for investment.

A force-field analysis of British Leyland at the time would have looked like the diagram in Figure 9.3.

Force-field analysis as an aid to change

The first stage in using force-field analysis is to identify all the forces at work on an organization. These may be external or environmental forces such as those described in Chapters 2 and 4 of this book. It is significant that, in the British Leyland example, three of the driving forces for change (threatened loss of subsidy, superior competition, loss of customer loyalty) are all external forces. Or the forces may be internal, as are all the remainder in the British Leyland case.

Figure 9.3Force-field analysis of British Leyland

Having identified all the forces and categorized them as driving or restraining forces, it is then possible to work out ways of enabling change through one of two overarching processes.

Increasing the driving forces

This may involve increasing the power of existing forces, or adding others to tip the balance in favour of change.

Of course, it is not strictly possible to increase the power of external forces – they are as they are and, by definition, the organization has no influence over environmental factors. Nevertheless, external forces can be made more powerful by initiatives to ensure that the members of an organization are aware and convinced of their existence, their impact and their implications; in other words, the threat involved in ignoring them.

It is easier to increase the power of internal forces. Managers can shout louder, staff can be sacked or laid off, new technology can be introduced without consultation.

Increasing the driving forces is often described as a ‘push’ strategy for managing change. However, Lewin's original research and later studies all show that push strategies are less effective and more prone to failure than the alternative. Typically, this is because people, when pushed, have a natural tendency to push back. So the restraining forces increase to balance out the increased driving forces.

Reducing the restraining forces

This, as you would expect, is alternatively known as a ‘pull’ strategy for managing change. It involves identifying and reducing or eliminating the causes of resistance.

In the British Leyland case, Michael Edwardes set out to reduce resistance by:

![]() confronting the unions. This was not painless. It resulted in several strikes and carried significant costs in lost production. Ultimately, however, the company achieved a management-union relationship based on partnership rather than mutual antagonism.

confronting the unions. This was not painless. It resulted in several strikes and carried significant costs in lost production. Ultimately, however, the company achieved a management-union relationship based on partnership rather than mutual antagonism.

![]() removing weak managers. Again, this was not without pain. Several managers lost their jobs. However, the argument was that workers could not be expected to trust incompetent managers and that managers who were not strong enough to do the jobs they were paid for did not deserve to have them.

removing weak managers. Again, this was not without pain. Several managers lost their jobs. However, the argument was that workers could not be expected to trust incompetent managers and that managers who were not strong enough to do the jobs they were paid for did not deserve to have them.

![]() increasing worker participation. Edwardes decided to involve shop-floor workers more in decision-making, as a way both of increasing their trust and of improving decisions. The following case study illustrates his approach.

increasing worker participation. Edwardes decided to involve shop-floor workers more in decision-making, as a way both of increasing their trust and of improving decisions. The following case study illustrates his approach.

CASE STUDY

Soon after joining, Edwardes visited the Longbridge factory. He walked down the production-line and stopped to talk to one of the hands. He asked him: ‘What's going wrong here?’

The hand replied: ‘I'm not going to tell you in front of this lot. But come back at 8 tomorrow morning. I'll tell you then.’

Edwardes came back the following morning and talked privately to the hand for an hour. The news spread through the business that here at last was a manager who kept his word and was willing to listen to the workers.

INVOLVING OTHERS

QUESTION

Based on what you have read so far, who do you think should be involved in managing change?

Our answer would include three categories of people:

![]() the problem-owner

the problem-owner

![]() the authority-holder

the authority-holder

![]() the solution-implementers.

the solution-implementers.

We looked briefly at each of these categories earlier in the chapter.

The problem-owner

In the context of managing change, this may not be quite the right title. Nevertheless, as change is intended to bring improvement and improvement is only necessary when things are not going as well as they should be, managing change and solving problems are closely linked.

It may seem unnecessary to include the problem-owner in our classification of people to be involved. Surely their involvement is so obvious as not to be worth mentioning? Surprisingly often, though, they are not involved. In a hierarchical organization, or one which takes a paternalistic view of its staff, decisions are taken to implement change (for example, in the form of changed procedures or documentation, or new operating practices) without consulting those who will be most directly affected by the change. The implied message is: ‘This will be good for you whether you like it or not.’

That message is a powerful way of increasing restraining forces against change by building fear or resentment. Any change initiative, however desirable, must be acceptable to the problem-owner if it is going to succeed.

CASE STUDY

When the British government, in response to the BSE crisis, passed a new law banning the sale of beef on the bone, many retailers ignored it and continued to sell T-bone steaks and oxtail. Customers – the problem-owners in this case -rejected the argument that the new law was good for them, preferring instead to be left to make their own decisions about whether they wanted the product.

The authority-holder

We could have said, quite simply, ‘the boss’. Authority figures have two important roles to play in managing change. First, they will often need to authorize the intended change and to make resources available to support it. It is therefore essential for them to know the nature of the change, its benefits and its implications.

Secondly, the authority of the boss is often a crucial driving force for change. Knowing that the boss is in favour, provided he or she has the respect of the workforce, and hearing from him or her the reasons for and the thinking behind the change, does much both to make the need for change convincing and to lessen the resistance.

The solution-implementers

We have already used the buzz words which relate to this group:

![]() consultation

consultation

![]() participation

participation

![]() gaining commitment

gaining commitment

![]() the need for communication.

the need for communication.

These apply to managing change just as much as they do to any other aspect of decision-making.

COMPETENCE SELF-ASSESSMENT

1What changes have recently taken place in the operation for which you are responsible?

2Based on the ten questions of problem-solving, how well were they managed?

3Does your organization favour analytical or creative problem-solving?

4Is its preferred approach consistent with the environment in which it operates?

5What changes would you like to make to achieve your vision for your operation?

6What driving forces promote those changes?

7What are the restraining forces in opposition to them?

8Are the members of your team in favour of change? How could you increase their support?

9What is your attitude to change? Why?

10What more could you do to increase your own manager's support for and commitment to change?