5Managing quality

Any discussion of quality starts off by facing an immediate problem – the difficulty of defining exactly what we mean by the term. Two quotations from the quality management literature will make this clear:

One of the main difficulties evident in the field of quality management is the variety of terms employed. Many are ill-defined and are used both interchangeably and inconsistently.

(Bell, McBride and Wilson, Managing Quality, Butterworth-Heinemann, 1994)

‘Is this a quality watch?’ Pointing to my wrist I ask a class of students – undergraduates, postgraduates, experienced managers – it matters not. The answers vary:

‘No, it's made in Japan’.

‘No, it's cheap’.

‘No, the face is scratched’.

‘How reliable is it?’

‘I wouldn't wear it’.

My watch has been insulted all over the world – London, New York, Paris, Sydney, Brussels, Amsterdam, Bradford!

Very rarely am I told that the quality of the watch depends on what the wearer requires from a watch – a piece of jewellery to give an impression of wealth or a time piece which gives the required data, including the date, in digital form? Clearly these requirements determine the quality.(John S. Oakland, Total Quality Management, Butterworth-Heinemann, 1989)

This second quotation provides a basis for the definition of quality which we shall be using throughout this chapter:

quality describes the extent to which a product or service meets customer requirements.

Two of the leading quality gurus express this idea in different, but similar phrases:

![]() ‘fitness for purpose or use’ (Joseph Juran, Quality Control Handbook, McGraw-Hill, 1979)

‘fitness for purpose or use’ (Joseph Juran, Quality Control Handbook, McGraw-Hill, 1979)

![]() ‘conformance to specification’ (Philip Crosby, Quality is Free, McGraw-Hill, 1979).

‘conformance to specification’ (Philip Crosby, Quality is Free, McGraw-Hill, 1979).

Paradoxically, our definition and the phrases we have quoted offer a warning against assuming that ‘quality’ is synonymous with ‘high quality’ or ‘Rolls Royce quality’. In some situations, customers may require and specify excellent quality. However, despite the title of Philip Crosby's book, it is important to recognize the essential trade-off between cost and quality standard. Consequently, in other situations customers may expect ‘good enough’ quality, without being prepared to pay the price for the highest standard.

CASE STUDY

The village of Charlton-on-Otmoor has no street lighting. A committee of villagers was asked by the Highways Department if they wanted it. They refused, preferring to rely on light from local houses rather than pay the extra council tax which street lighting would involve.

Marks and Spencer, Bhs and Littlewoods all offer men's shirts, but of different standards and at different prices. Each range is intended for a different market. If all three retailers offered the same high standard, they would fail to meet the expectations of customers looking for a cheaper product.

Our introduction so far brings together themes from earlier chapters of this book.

IMAGE AND EXPECTATIONS

At a macro level, it is important for operations managers to be aware of:

![]() the markets which the organization has chosen to serve

the markets which the organization has chosen to serve

![]() the balance between product or service standard and price or cost which the organization has chosen to offer

the balance between product or service standard and price or cost which the organization has chosen to offer

![]() the expectations and requirements of customers in those market segments

the expectations and requirements of customers in those market segments

![]() their own contribution to achieving the organization's chosen standards and costs

their own contribution to achieving the organization's chosen standards and costs

![]() their contribution to meeting customer requirements.

their contribution to meeting customer requirements.

At a macro level, or, in different words, at the level of meeting the requirements of internal customers, operations managers need to understand:

![]() who those internal customers are

who those internal customers are

![]() the nature of their needs and expectations

the nature of their needs and expectations

![]() how much they are prepared to pay to have those needs met

how much they are prepared to pay to have those needs met

![]() the customers’ views of the trade-off between standard and cost.

the customers’ views of the trade-off between standard and cost.

In the title to this section we have linked image and expectations. In strategic marketing terms, this linkage is easy to identify.

CASE STUDY

Oxfam and Scope (formerly the Spastics Society) both operate charity shops. Oxfam has a reputation for higher priced and higher standard second-h and items than Scope. As a result, customers go to Oxfam for recent hardback and paperback titles, but to Scope for a cheap holiday read. Similarly, contributors give old items to Scope, new items to Oxfam. In both cases, the image of the organization and the expectations of its customers coincide.

The linkage is more tenuous when it comes to internal markets. However, three considerations should be borne in mind:

![]() Internal suppliers are increasingly subject to external competition.

Internal suppliers are increasingly subject to external competition.

![]() ‘Doing without’ is a valid option for some internal customers.

‘Doing without’ is a valid option for some internal customers.

![]() Internal suppliers have an image as much as external customers do.

Internal suppliers have an image as much as external customers do.

In consequence, it is important for internal suppliers to assess their image in the internal marketplace and to decide:

![]() whether that image is consistent with the standard of the product or service offered

whether that image is consistent with the standard of the product or service offered

![]() whether the image is consistent with customer expectations

whether the image is consistent with customer expectations

![]() whether the standard is consistent with the expectations.

whether the standard is consistent with the expectations.

Notice that we have stressed ‘consistent with’. You will find references in the total quality literature to:

![]() exceeding customer expectations

exceeding customer expectations

![]() delighting customers.

delighting customers.

However, we have also pointed out that quality has a cost. Therefore, it is necessary to evaluate the cost implications of quality improvement, in order to establish whether internal customers are prepared to pay their share of that cost.

THE LANGUAGE OF QUALITY

Three terms recur frequently in discussions about quality. These are:

![]() quality control

quality control

![]() quality assurance

quality assurance

![]() total quality management.

total quality management.

The three processes are very different in:

![]() their objectives

their objectives

![]() the operational stage to which they apply

the operational stage to which they apply

![]() the systems necessary to support them

the systems necessary to support them

![]() the actions resulting from them.

the actions resulting from them.

Let us examine each in turn.

Quality control

Quality control is the traditional process of comparing product or service outputs with customer requirements or specifications. Its purpose is to identify those outputs which do meet, and those which do not meet, the quality specification. Typical systems used in the quality control process are:

![]() quality inspection, where inspectors assess outputs against specification on a pass/fail or go/no go basis

quality inspection, where inspectors assess outputs against specification on a pass/fail or go/no go basis

![]() output sampling, which reduces the cost of inspection by assessing, say, one in ten of outputs

output sampling, which reduces the cost of inspection by assessing, say, one in ten of outputs

![]() statistical process control, which identifies the sources of variance in output quality.

statistical process control, which identifies the sources of variance in output quality.

We shall consider these in more detail later in this chapter.

The significant feature of quality control is that it takes place after the event. In other words, it is applied to products and services after they have been finished. This process is easiest to recognize in a manufacturing context, where, for example, finished components are checked for fit or engines are bench-tested when they have been built. However, the quality control process is applied elsewhere as well:

![]() Proof-reading a letter before it is sent out is a form of quality control.

Proof-reading a letter before it is sent out is a form of quality control.

![]() Editing a book to ensure the content is accurate is a form of quality control.

Editing a book to ensure the content is accurate is a form of quality control.

![]() Checking your supermarket bill is a form of quality control, although here it is the customer, rather than the supplier, who does the controlling.

Checking your supermarket bill is a form of quality control, although here it is the customer, rather than the supplier, who does the controlling.

Actions resulting from quality control are either:

![]() acceptance of outputs which meet the specification, or

acceptance of outputs which meet the specification, or

![]() rejection of outputs which do not meet the quality standard.

rejection of outputs which do not meet the quality standard.

Quality assurance

Where quality control concentrates on outputs, quality assurance focuses on the various stages of the transformation process. Its objective is therefore to ensure that the methods and procedures which bring about transformation are designed to achieve the required output quality. Thus, while quality control takes place after the event, quality assurance takes place during the event.

Typical quality assurance systems are:

![]() ISO 9000

ISO 9000

![]() reviews of quality policy

reviews of quality policy

![]() flow-charting

flow-charting

![]() design of control documents.

design of control documents.

Because quality assurance sets out to prevent quality problems, actions resulting from it are likely to be:

![]() process redesign

process redesign

![]() systems implementation

systems implementation

![]() streamlining

streamlining

![]() clarification of procedures

clarification of procedures

![]() allocation of responsibilities

allocation of responsibilities

![]() improved documentation.

improved documentation.

Total quality management

Total quality management (TQM) is an all-embracing philosophy which is far wider in its application than the two processes we have considered so far. It is intended to improve the effectiveness and flexibility of businesses as a whole, by organizing and involving the entire organization: every department, every team, every activity, every individual. It is TQM which has given rise to the concept of the internal customer and extended the idea of customer expectations beyond that of output quality alone to include such things as delivery, customer relations, communication and added value.

The TQM philosophy therefore applies before, during and after the event. Support systems will cover a huge range of activities:

![]() customer consultation and feedback

customer consultation and feedback

![]() training

training

![]() process improvement

process improvement

![]() systems design

systems design

![]() conformance reviews.

conformance reviews.

The outcomes of TQM are therefore nothing less than a radical reappraisal of all attitudes, activities and procedures throughout the organization.

It would be dangerous to assume, though, that quality control is less desirable than quality assurance, or that quality assurance is less desirable than total quality management:

![]() Quality control is largely a local initiative. Output inspection is a fundamental part of operations management.

Quality control is largely a local initiative. Output inspection is a fundamental part of operations management.

![]() Quality assurance, on the other hand, will involve a review of procedures which may well lie outside the scope of operations management alone.

Quality assurance, on the other hand, will involve a review of procedures which may well lie outside the scope of operations management alone.

![]() Total quality management requires the support and involvement of everyone in the organization, from top to bottom and throughout all departments.

Total quality management requires the support and involvement of everyone in the organization, from top to bottom and throughout all departments.

So, as you read on, keep two questions in mind:

![]() Which of these techniques do I have the authority to implement?

Which of these techniques do I have the authority to implement?

![]() What actions could and should I take to support wider initiatives?

What actions could and should I take to support wider initiatives?

QUALITY CONTROL

All these techniques are designed to detect the incidence of outputs failing to meet specification. In addition, statistical process control seeks to identify the causes of poor quality, as a first step towards eliminating them. It thus forms a half way house between quality control and quality assurance.

As with any form of performance monitoring, quality control techniques depend on having objective standards against which to measure outputs. As elsewhere, these should be quantified as far as possible, though, when it comes to quality controlling service outputs, it may not always be possible to develop genuinely objective, quantified standards.

Inspection

To be truly effective, quality inspection should take place at each stage of an operation, starting with the first input from an external customer. As we have hinted, writers on quality management are inclined to be dismissive of quality inspection. A quote from Bell, McBride and Wilson (Managing Quality, Butterworth-Heinemann, 1994) confirms this point:

There are many systems which can be put into place to minimize the amount of scrap and rework (wrong first time) output from a system. Perhaps the simplest is incoming goods inspection. This is put in place for two key reasons. First, There is an understanding that by letting poor-quality goods enter our system, it is difficult to recover the situation and produce a quality product. Second, we are saying that we do not trust our suppliers and thus our own vendor-rating system. Perhaps the most significant outcome of this scenario is that our organization must perform non-value-added activity in order to achieve an acceptable quality of incoming goods. Through the employment of goods inwards inspectors a very high price is being paid for a product which should have been delivered correctly in the first place.

None the less, quality inspection of incoming goods is an essential fact of life in the real, imperfect world. Consider the consequences of not inspecting incoming goods in the following situations:

![]() A retail store receives a supplier delivery by lorry. It has travelled a long way. Consider the consequences of the warehouse manager signing for the delivery without checking:

A retail store receives a supplier delivery by lorry. It has travelled a long way. Consider the consequences of the warehouse manager signing for the delivery without checking:

![]() whether all the items on the delivery note are really there

whether all the items on the delivery note are really there

![]() whether any have been damaged in transit.

whether any have been damaged in transit.

![]() A small training partnership is about to run a training event which starts on Monday at a hotel a hundred miles away. The handouts have just arrived from the local copy shop. Consider the consequences of packing them into the trainer's car without first checking:

A small training partnership is about to run a training event which starts on Monday at a hotel a hundred miles away. The handouts have just arrived from the local copy shop. Consider the consequences of packing them into the trainer's car without first checking:

![]() whether the right number of copies have been taken

whether the right number of copies have been taken

![]() whether multipage handouts have been collated and stapled in the right order.

whether multipage handouts have been collated and stapled in the right order.

![]() A senior civil servant has been asked to prepare a written answer to a parliamentary enquiry. The answer will be sent to the Member of Parliament who raised the enquiry and a copy placed in the House of Commons library. Consider the consequences if the civil servant does not check that the answer, which has been researched by a subordinate and typed by a secretary, is accurate and relevant in content and contains no grammatical, spelling or typing errors.

A senior civil servant has been asked to prepare a written answer to a parliamentary enquiry. The answer will be sent to the Member of Parliament who raised the enquiry and a copy placed in the House of Commons library. Consider the consequences if the civil servant does not check that the answer, which has been researched by a subordinate and typed by a secretary, is accurate and relevant in content and contains no grammatical, spelling or typing errors.

In each situation, it is apparent that failure to check input quality runs the risk of leading to:

![]() overcharging

overcharging

![]() disruption or inconvenience

disruption or inconvenience

![]() final customer dissatisfaction

final customer dissatisfaction

![]() a loss of face or reputation

a loss of face or reputation

![]() poor output quality.

poor output quality.

Even so, it is important to realize that quality control is a costly technique. It requires resources (staff, equipment). It leads to scrap or reworking. It has no possible outcome other than acceptance or rejection. Nevertheless, it is an essential process until such time as every supplier is totally competent and every input and output wholly reliable.

Sampling

Sampling is one way of reducing inspection costs. It is a worthwhile technique where the product or service is complex, making the cost of inspection high, or where the historical rejection rate is low. The quality of samples taken from a batch will lead to a decision as to whether the total batch should be accepted or rejected.

Compared with full inspection, sampling brings the following benefits:

![]() time saving

time saving

![]() reduced handling damage

reduced handling damage

![]() fewer staff required

fewer staff required

![]() more efficient rejection, based on batch rather than individual items.

more efficient rejection, based on batch rather than individual items.

However, it brings drawbacks too:

![]() the risk of accepting poor quality batches

the risk of accepting poor quality batches

![]() the risk of rejecting good items

the risk of rejecting good items

![]() increased likelihood of rejection later in the operation

increased likelihood of rejection later in the operation

![]() less reliable information about inputs and outputs.

less reliable information about inputs and outputs.

To be effective, sampling must be carried out rigorously. In other words, the samples selected for inspection must be chosen according to a sampling method which guarantees that they will be representative and the inspection must be carried out and acceptance/rejection decisions taken with full regard to the seriousness of various defects. The reality of both sampling and inspection is usually rather different:

![]() Samples are chosen because they are convenient rather than representative.

Samples are chosen because they are convenient rather than representative.

![]() Samples are chosen on a regular rather than random basis.

Samples are chosen on a regular rather than random basis.

![]() Outputs which are difficult to access are not sampled.

Outputs which are difficult to access are not sampled.

![]() Batches are rejected for minor defects.

Batches are rejected for minor defects.

![]() Major but infrequent defects slip through.

Major but infrequent defects slip through.

To overcome these problems, quality sampling requires information on:

![]() the size of sample which will be statistically reliable

the size of sample which will be statistically reliable

![]() a way of deriving batch quality from sample quality

a way of deriving batch quality from sample quality

![]() those aspects of quality to be measured and how accept/reject decisions are taken as a result.

those aspects of quality to be measured and how accept/reject decisions are taken as a result.

Statistical process control

The technique of statistical process control is based on simple and obvious concepts. However, its implementation involves some complex collection and analysis of data and is therefore likely to require additional resources and senior management support.

Fundamental to operations management is the idea that applying the same transformation process to the same inputs will result in the same outputs- the assumption that the process will remain constant. After all, any batch or continuous operation relies on producing consistent or constant output standards at all times.

Statistical process control starts from the recognition that, in fact, any process, product or service is subject to variation. It also recognizes that such variations stem from two types of causes:

![]() ‘normal’ causes which are inherent in the system, possible to reduce but impossible to eliminate and outside the opera-tor's control

‘normal’ causes which are inherent in the system, possible to reduce but impossible to eliminate and outside the opera-tor's control

![]() ‘special’ causes which are unusual factors, resulting insignificant variations and which can normally be corrected by the operator.

‘special’ causes which are unusual factors, resulting insignificant variations and which can normally be corrected by the operator.

Examples of normal causes are:

![]() inconsistencies in raw materials

inconsistencies in raw materials

![]() unreliable equipment

unreliable equipment

![]() inadequately trained staff

inadequately trained staff

![]() poor product or service design.

poor product or service design.

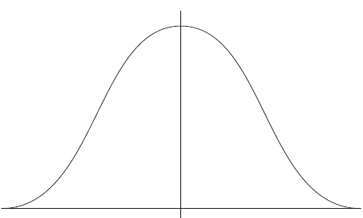

Any of these causes will result in variations which will occur according to a normal distribution (traditionally known as a bell-shaped curve), as shown in Figure 5.1.

Figure 5.1 Normal distribution

What this means is that variations from the norm will occur in a regular pattern on either side of the mean in Figure 5.1.

Special causes may be:

![]() equipment breakdown

equipment breakdown

![]() faulty adjustment

faulty adjustment

![]() operator oversight.

operator oversight.

The pattern of special variations will be irregular – some outputs will be adversely affected, others will not.

Statistical process control operates ( and this is where the complex analysis comes in) by plotting the pattern of normal variations and super-imposing special variations onto them. This process can be applied to individual inputs and to individual quality measures, in such a way as to identify the causes of variation, those which are under the operator's control and those which require management intervention. Thus, as we have said, the technique starts by identifying defects in the form of variations, but moves on to isolate the causes, as a first step to removing them.

RIGHT FIRST TIME

We have adopted this title, rather than the quality assurance phrase we used earlier, because we believe it highlights the key difference between quality control on one hand and quality assurance on the other. Quality control rejects poor quality after it has happened. Quality assurance attempts to ensure that it does not happen at all.

We have already mentioned that the implementation of quality assurance is often associated with the introduction of ISO 9000 or one of its equivalents- ISO 9001, 9002 or 9003. However, it is again necessary to differentiate between theory and practice.

Applied as it was originally intended, the ISO 9000 series provides a methodology with which to establish, document and maintain an effective quality system which will demonstrate to customers an organization's commitment to quality and its ability to meet their quality needs. It expects a critical examination of all of an organization's procedures which have an impact on quality and careful attention to improving and refining them. The process of documentation is intended simply to ensure that best practice, once established, is maintained.

The reality, though, has been different in many cases. Organizations have been content simply to document existing procedures, without taking the essential first step of asking whether they genuinely deliver quality. It is this approach which has given ISO 9000 a bad name!

CASE STUDY

A London-based consultancy with a poor reputation for late delivery and low levels of customer satisfaction never the less gained ISO 9001 by carefully documenting its invoicing and consultant booking procedures.

So, what should a quality assurance process look like? Quality assurance involves an analysis of all the processes and procedures in an organization which lead ultimately to the delivery of a product or service to the customer. Each process and procedure is subject to examination, to identify the extent to which it meets the customer's expectations or requirements – the definition of quality that we have used all through this chapter. Traditionally, quality assurance has concentrated on the needs of the final customer. From this viewpoint, all processes and procedures are seen as a single operation – that of creating final customer satisfaction.

Although it would be hard to argue with this philosophy, it has sometimes had the unfortunate result of forcing staff to jump through procedural hoops which, whilst helpful to the final customer, introduce significant inconvenience or disruption to the staff concerned along the way.

As described elsewhere in this book, the competitive tendering process used by local and national government is intended to achieve the highest level of value for money for the final customer – the taxpayer. However, along the way, the process will involve:

![]() national advertising to attract expression of interest

national advertising to attract expression of interest

![]() the publication of an invitation to tender

the publication of an invitation to tender

![]() briefings for potential suppliers

briefings for potential suppliers

![]() an evaluation of bids

an evaluation of bids

![]() responses to unsuccessful bidders, explaining why they were unsuccessful.

responses to unsuccessful bidders, explaining why they were unsuccessful.

Typically, it will require significant time and staff resources from the originating department, contracts and finance.

The care necessary to make the process error-proof in order to guarantee value for money can mean that the originating department, desperate for its supplies, has to wait six months before the contract is let.

Nowadays, under the influence of total quality management, quality assurance is more likely to view each stage in the creation of final customer satisfaction as a separate operation, each one intended to satisfy the needs of the next internal customer in the value chain.

Quality assurance involves the following steps:

![]() mapping the operation

mapping the operation

![]() identifying the processes and procedures which support each stage

identifying the processes and procedures which support each stage

![]() assessing each against criteria of customer satisfaction

assessing each against criteria of customer satisfaction

![]() highlighting the need for improvement

highlighting the need for improvement

![]() monitoring the improvement.

monitoring the improvement.

Central to the philosophy of quality assurance is the principle that those responsible for each activity are best placed to evaluate and improve it. However, we have already pointed out the risks of delegated responsibility. Consequently, quality assurance is usually carried out by a network of local project teams, co-ordinated by a central supervising committee or task force.

Mapping the operation/identifying processes

It is the responsibility of the central committee to map the total operation, highlighting the points where handover takes place between functions and isolating individual processes. It is then for local teams to develop more detailed maps of their individual activities.

The more comprehensive these maps, the more useful they will be. As a minimum, they should show the separate steps of a process, the inputs required and the procedures in place.

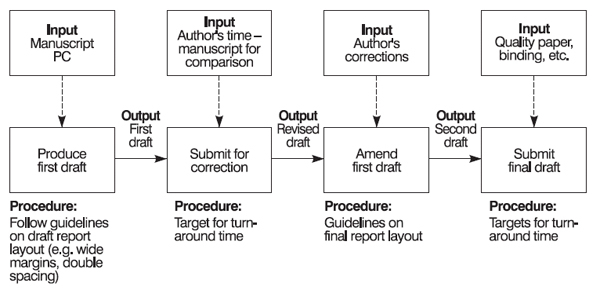

A simple process flow chart is shown in Figure 5.2 for the production of a word processed report.

Figure 5.2 Report production process

Assessing/highlighting improvement needs

These stages are central to the process. They should involve both supplier and customer. Their intention is to review critically everything which happens to support each activity and, if necessary, to identify where and why it is failing.

For example, our production of a word processed report requires inputs of an author's manuscript, time, physical stocks of paper and covers. It also depends on the implementation of various procedures and targets. Recognizing that author and word processor (WP) operator are either customer or supplier at different stages of the process, a critical review should ask:

![]() Is the author's manuscript legible?

Is the author's manuscript legible?

![]() Does the PC have a suitable word processing package?

Does the PC have a suitable word processing package?

![]() Is the author available to make corrections?

Is the author available to make corrections?

![]() Are the layout guidelines up to date and easy to understand?

Are the layout guidelines up to date and easy to understand?

![]() Are the turnaround targets realistic, in view of the WP operator's workload and the author's availability?

Are the turnaround targets realistic, in view of the WP operator's workload and the author's availability?

![]() If not, what should change?

If not, what should change?

![]() Are suitable covers and paper readily available?

Are suitable covers and paper readily available?

Potential improvement needs from this analysis might include:

![]() a more user-friendly WP package

a more user-friendly WP package

![]() layout guidelines to be rewritten

layout guidelines to be rewritten

![]() faster access to author for corrections

faster access to author for corrections

![]() paper stocks to be held closer to the WP operator's desk.

paper stocks to be held closer to the WP operator's desk.

Implementing and monitoring improvement

It is unusual for quality assurance methods to be introduced for a single process. Usually, they will be applied across an organization, or at least to a whole department. The responsibility for the implementation of improvement is therefore likely to be spread.

This is where the central committee has a further task to do. Having mapped the overall operation, allocated individual activities for review and supervised that work against agreed deadlines, it is important for them now to co-ordinate the outcomes. For example, some outdated or inaccurate procedures, like our report layout guidelines, may emerge as improvement needs across the organization. Others, like the maintenance or ordering of stationery stock, may require company-wide or local action.

Yet other improvement needs – like faster or easier access to the author for corrections – will need to be implemented through negotiation between the parties concerned.

Overall, though, the quality assurance process is designed to result inaction which will eliminate or correct any factors which prejudice the achievement of customer satisfaction, both at the end of the value chain and at any stage along it.

As we pointed out at the beginning of the section, quality assurance introduces systems which ensure, as far as possible, that products and services are ‘right first time’. It may therefore seem illogical to suggest that those systems, once introduced, need monitoring. However, all systems are subject to neglect, corruption and abuse.

Monitoring should focus on three areas:

![]() current suitability

current suitability

![]() systems maintenance

systems maintenance

![]() output monitoring.

output monitoring.

Current suitability

This is to do with the extent to which systems are still relevant to the organization's current operating environment. It is quite likely that, over time, the goals and objectives of the organization have changed, improved technology has become available or operational outputs are needed sooner or quicker. Faced with any of these factors, it will be necessary to review, update or upgrade the systems – and that can only be done if the divergence between the environment and the system has been recognized.

Systems maintenance

Over time, systems and processes degrade and become less efficient. As a result of ignorance, laziness or attempts to keep a sagging system in operation, it will be changed, simplified or made more complex. The first stage of systems maintenance is, as just described, to assess its current suitability. If it is found still to be suitable, the next stage is to establish whether it is being used as originally designed.

If not, this may show up a need for:

![]() staff training

staff training

![]() a change in attitude

a change in attitude

![]() an evaluation of the match between the needs of the system and available resources

an evaluation of the match between the needs of the system and available resources

![]() an assessment of the costs and benefits of the outputs from the system.

an assessment of the costs and benefits of the outputs from the system.

Output monitoring

Quite simply, this is a question of establishing whether outputs continue to create quality by meeting customer needs. The needs may have changed, or the quality of the output may have declined. In either case, this highlights a need to go back into the quality assurance cycle once more.

QUALITY IMPROVEMENT

We have chosen this title for our final section because it is a fair reflection of the central theme of total quality management, our last and most ambitious approach to quality management.

As you will have gathered, TQM is a philosophy which puts customer satisfaction at the heart of the organization. Put in those terms, it may not sound particularly revolutionary. After all, for many years organizations, particularly trading companies, have operated with slogans like:

![]() ‘The customer is always right.’

‘The customer is always right.’

![]() ‘The customer is our only reason for existence.’

‘The customer is our only reason for existence.’

In most of us, though, the cynic (or the realist!) recognizes that, whilst such slogans were relevant to – and to a greater or lesser extent accepted by – customer-facing staff like members of the sales force or retail shop assistants, their application did not go much further.

With hindsight, as we explored in Chapter 4, it is obvious that:

![]() hospitals have customers

hospitals have customers

![]() schools have customers

schools have customers

![]() churches have customers

churches have customers

![]() charities have customers

charities have customers

![]() government departments have customers.

government departments have customers.

Nevertheless, it is only since the late 1970s that this point has been recognized. And that recognition of colleagues and other departments as internal customers is a process which many organizations are still struggling with.

CASE STUDY

A government department, as part of its competence-based training initiative, decided to introduce a package on TQM. The consultants hired to write the package found, to their consternation, that neither the trainers working the re, nor the Training Manager involved, could understand the idea of ‘internal customers’. The resulting package had more to do with quality control and quality assurance than it did with TQM!

The implementation of a TQM philosophy demands:

![]() commitment and support from all levels of management, starting at the top. This theme was developed, along with other issues, in Chapter 2.

commitment and support from all levels of management, starting at the top. This theme was developed, along with other issues, in Chapter 2.

![]() A culture which encourages customer focus, experimentation and improvement. This theme was introduced in Chapter 4 and is expanded further in Chapters 8 and 9.

A culture which encourages customer focus, experimentation and improvement. This theme was introduced in Chapter 4 and is expanded further in Chapters 8 and 9.

![]() managers who are adept at managing people. This is the main thrust of Chapter 10.

managers who are adept at managing people. This is the main thrust of Chapter 10.

![]() a view of the organization as a total system, made up of activities designed to create customer satisfaction. This theme was explored earlier in this chapter.

a view of the organization as a total system, made up of activities designed to create customer satisfaction. This theme was explored earlier in this chapter.

![]() a practical, empowering approach to managing people. This is a recurrent theme of this book, particularly in Chapters 3, 6, 8, 9 and 10.

a practical, empowering approach to managing people. This is a recurrent theme of this book, particularly in Chapters 3, 6, 8, 9 and 10.

You will recognize from this that the TQM philosophy has had a major impact on the approaches, techniques, processes and attitudes which now underpin operations management. However, when you remember that we defined the purpose of operations as being to provide a service to the customer or client, this will come as no surprise!

COMPETENCE SELF-ASSESSMENT

1How does your organization define quality? Would you agree with that definition?

2What image do your customers have of your operation? Is it consistent with:

(a) the standard you deliver?

(b) their requirements?

3How could you use the following quality control methods to improve quality in your operation:

(a) inspection?

(b) sampling?

(c) statistical process control?

4How could you use the following quality assurance techniques to improve quality in your operation:

(a) operation mapping?

(b) evaluating processes and procedures?

(c) highlighting improvement needs?

(d) monitoring systems?

5What management support would you need to implement your chosen methods?

6What benefits would you highlight to gain the support?

7How customer-focused is:

(a) your organization?

(b) your operation?

8Does your organization have a culture which would support TQM?

9If not, what would have to change?

10How much of TQM philosophy can you implement personally?