10Managing people

‘At last!’ exclaimed our personnel officer. ‘A chapter on people – and about time, too, if I may say so. How this book expects anyone to manage operations effectively without being able to manage people, I cannot imagine. Motivation, communication, empowerment, involvement, training, performance appraisal – they're all central to a modern manager's job. It's going to be a struggle to fit all of those into a single chapter, I can tell you.’

‘Now hold on’, said the marketing manager. ‘This isn't a human resources textbook. It's not fair for you to expect comprehensive coverage of your subject. I'd argue that customer service is central to the modern manager's job, too – but this isn't a marketing textbook, either. So, we've only had a few references to marketing principles. In the same way, accounting has only cropped up a few times. But I bet our beloved accountant would argue that a good manager has to be able to use accounting techniques as well.’

‘That's right’, agreed the production supervisor. ‘This book is about operations management. As I see it, people are resources to be used in transforming inputs into outputs. Important resources, of course. But no more important than machinery, equipment, space, raw materials, systems and procedures. I certainly want to learn more about managing people – but only to help me be a more effective operations manager. The fancy stuff can wait for a different book!’

Those early exchanges put this chapter's coverage of people management into context and into proportion. The subject of operations management incorporates ideas and techniques from a wide range of management disciplines:

![]() marketing and particularly customer service

marketing and particularly customer service

![]() quality management

quality management

![]() production scheduling

production scheduling

![]() stock control and stock management

stock control and stock management

![]() capacity management

capacity management

![]() strategic planning

strategic planning

![]() objective setting

objective setting

![]() output and performance management

output and performance management

![]() problem-solving and decision-making

problem-solving and decision-making

![]() managing health and safety

managing health and safety

![]() financial accounting.

financial accounting.

It is therefore important to recognize that operations management is a generalist, rather than an expert, function. That comment is not intended to belittle the function. Rather, it is an acknowledgement of the old adage that: ‘Experts are people who know more and more about less and less, to the point where they know almost everything about nothing at all.’

Consequently, this chapter is consistent with the wishes of the production supervisor. It is intended to deal with those aspects of the management of people which have an impact on operations management, but without going into exhaustive detail.

Nevertheless, we would agree with the personnel officer that people management is a wide-ranging topic. Therefore, the chapter has a lot of ground to cover, particularly in view of the fact that, in the context of operations management, the people to be managed are not just subordinates, but colleagues and bosses as well.

In order to cover this ground, the chapter is split into the following sections:

Managing subordinates

![]() assessing ability and potential

assessing ability and potential

![]() communication and involvement

communication and involvement

![]() empowerment

empowerment

![]() developing capability.

developing capability.

Managing colleagues

![]() consulting and informing

consulting and informing

![]() developing confidence.

developing confidence.

Managing the boss

![]() representing your people

representing your people

![]() upward communication

upward communication

![]() seeking direction.

seeking direction.

MANAGING SUBORDINATES

The way a manager manages subordinates is dependent on three factors:

![]() personality and personal style

personality and personal style

![]() the culture of the organization

the culture of the organization

![]() the nature of the work.

the nature of the work.

Some managers feel more comfortable giving orders, in the expectation that subordinates will follow them. This may be the result of personality, or of the work environment in which managers have learnt their trade.

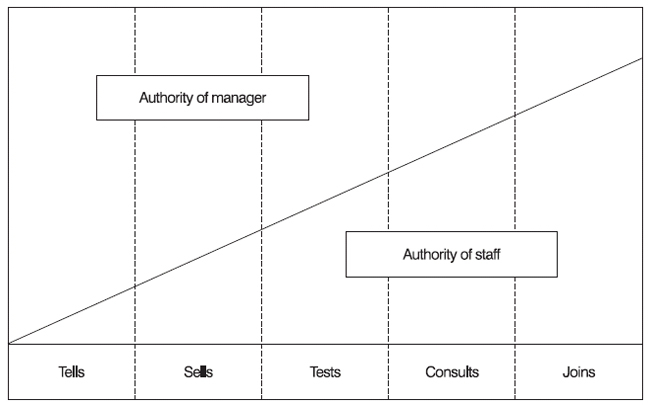

Tannenbaum and Schmidt, two American psychologists, developed a model of the use of authority by managers (see Figure 10.1).

Figure 10.1Tannenbaum–Schmidt model

The Tannenbaum–Schmidt continuum of decision-making is based on the premise that any management decision requires a finite amount of input. The more input from the manager to a decision (in the shape of authority), the less scope there is for input from staff (in the shape of involvement in the decision).

This model incorporates five different management styles of decision-making, as described below:

![]() In the telling style, the manager identifies the problem or the need for a decision, considers alternatives and chooses one of them. Staff are informed of the decision and instructed to implement it. Their thoughts or feelings are not taken into account.

In the telling style, the manager identifies the problem or the need for a decision, considers alternatives and chooses one of them. Staff are informed of the decision and instructed to implement it. Their thoughts or feelings are not taken into account.

![]() In the selling style, the manager identifies the problem and decides on a solution. However, there is a recognition that the decision may meet with resistance from staff affected by it. In order to deal with that resistance, the decision is not simply announced. Instead, the manager makes an effort to sell it by promoting the benefits the decision will bring to staff.

In the selling style, the manager identifies the problem and decides on a solution. However, there is a recognition that the decision may meet with resistance from staff affected by it. In order to deal with that resistance, the decision is not simply announced. Instead, the manager makes an effort to sell it by promoting the benefits the decision will bring to staff.

![]() In the testing style, the manager reaches a tentative decision. But, before that decision is finalized, the manager presents it and tests its viability by judging staff reactions. The manager still reserves the right to take the final decision.

In the testing style, the manager reaches a tentative decision. But, before that decision is finalized, the manager presents it and tests its viability by judging staff reactions. The manager still reserves the right to take the final decision.

![]() In the consulting style, the manager identifies the problem and presents it to staff for suggested solutions. The manager evaluates staff suggestions and chooses the one which seems most promising.

In the consulting style, the manager identifies the problem and presents it to staff for suggested solutions. The manager evaluates staff suggestions and chooses the one which seems most promising.

![]() In the joining style, the manager identifies the problem, but then passes it to staff to analyse and decide on a solution. The manager may join the staff in this decision-making process, but the group is given the right to make the final decision and the manager agrees to implement it.

In the joining style, the manager identifies the problem, but then passes it to staff to analyse and decide on a solution. The manager may join the staff in this decision-making process, but the group is given the right to make the final decision and the manager agrees to implement it.

QUESTION

Which of these decision-making styles is most natural for you?

There is no right answer to this question. Your style will have developed as a result of what is natural for you on one hand, and the expectations of the organizations in which you have worked on the other.

Organizations have a marked tendency to recruit and develop both managers and staff in their own image. So, for example, organizations with an autocratic style will develop managers who are comfortable giving orders and recruit staff who are happy obeying them.

In the 1980s, Do-It-All, the chain of DIY superstores, had a culture of unquestioning obedience. In the course of a training event, one manager remarked: ‘If I tell a member of my staff to jump, the only question I expect is “How high?”’

So, where does organizational style come from? In part from history, but also in large part from the nature of the work. Organizations that depend on routine, consistent work tend to have a style which demands obedience to instructions. At the other extreme, organizations that depend on creativity and innovation favour a consultative style which expects and welcomes staff who question routines, procedures and instructions.

However, this apparently universal picture is overly simplistic. Consider the following example.

CASE STUDY

At first glance, the military is a classic example of an organization which demands obedience without question. In fact, the reality in the British Army is significantly different. The unpredictability of modern battle makes it essential for soldiers at all levels to be able to make decisions for themselves. Consequently, their training emphasizes situation analysis, solution generation and the evaluation of alternatives.

At the same time, there are still situations which demand automatic obedience. As a senior officer recently remarked: ‘We expect our personnel to think for themselves. But they are all dependent on each other. So there will always be life-threatening situations where they need to follow orders without question.’

The sections on managing subordinates which follow therefore seek to take account of personal style, the expectations of your organization, as well as best current practice and the demands of operational effectiveness.

Assessing ability and potential

In earlier chapters of this book, we have referred to the techniques and benefits of performance appraisal. In summary, the process involves:

![]() reviewing past performance against objectives

reviewing past performance against objectives

![]() identifying strengths and weaknesses of performance

identifying strengths and weaknesses of performance

![]() agreeing future objectives

agreeing future objectives

![]() agreeing any training or support needed to achieve future objectives and deal with past weaknesses.

agreeing any training or support needed to achieve future objectives and deal with past weaknesses.

Performance is then monitored informally on an ongoing basis and discussed with the subordinate, in preparation for the next formal appraisal review or interview.

The way you approach performance appraisal will depend on:

![]() the system in place in your organization

the system in place in your organization

![]() your view of what will be required of your operation in future and the operating procedures you expect your staff to use.

your view of what will be required of your operation in future and the operating procedures you expect your staff to use.

There are two ways of handling any appraisal system, one unproductive and the other productive. The way you are used to is likely to depend on the culture of the organization in which you work.

The unproductive approach to appraisal involves the mechanical completion of the documentation any such system demands. The personnel or human resource department sends out the papers and sets deadlines for their return. Managers tick boxes, award grades, write out objectives largely based on those set for the last period and agree training in a discussion which mainly takes the form of: ‘Here's the brochure. Is there anything you fancy doing in that list?’

CASE STUDY

A trainee from a major high street retailer attended an in-house retail marketing course. When asked why he was there and what he wanted to get out of the course, his answer was: ‘Well, I've done everything on the list except marketing and retail finance – and I wasn't keen on doing the finance.’

Of course, that approach, as we pointed out in our earlier chapter, sends some important messages to the workforce. They include:

![]() We don't really value our own people.

We don't really value our own people.

![]() We're not interested in developing skills.

We're not interested in developing skills.

![]() Managing people just involves going through the motions.

Managing people just involves going through the motions.

In a minority of cases, the system is so designed that there is no alternative to this approach. Deadlines for turning round the paperwork are so tight that the time is simply not available for managers and subordinates to prepare for and conduct the necessary interviews in a meaningful way.

More often, however, the system is abused because managers and subordinates have failed to recognize the potential benefits it offers. The benefits of an effective appraisal system are:

![]() The workforce feels valued.

The workforce feels valued.

![]() Individuals gain knowledge, skills and experience which are relevant both to their current jobs and to future careers.

Individuals gain knowledge, skills and experience which are relevant both to their current jobs and to future careers.

![]() Performance throughout the organization improves.

Performance throughout the organization improves.

![]() Output increases.

Output increases.

![]() Errors, costs and waste decrease.

Errors, costs and waste decrease.

The productive use of appraisal involves:

![]() Giving honest, accurate, but constructive feedback on past performance.

Giving honest, accurate, but constructive feedback on past performance.

![]() Setting objectives which are stretching but achievable.

Setting objectives which are stretching but achievable.

![]() Arranging training (not just formal courses but also coaching, self-study, guided experience) which is relevant to the individual.

Arranging training (not just formal courses but also coaching, self-study, guided experience) which is relevant to the individual.

![]() Regarding appraisal as a continuous approach, not just a matter of completing the forms once or twice a year.

Regarding appraisal as a continuous approach, not just a matter of completing the forms once or twice a year.

The linkage between operational needs and appraisal is an important one. It is also a two-way process. Earlier in this book we looked in detail at continuous improvement and managing change. Changes to required outputs – their nature or quantity – will depend partly for their success on your subordinates’ ability to deliver them. Consequently, you need to ask yourself:

![]() Are my staff currently capable of producing more, better or otherwise different outputs?

Are my staff currently capable of producing more, better or otherwise different outputs?

![]() If not, do they have the potential to learn?

If not, do they have the potential to learn?

![]() If not, can these changes to output be achieved without demanding more from my staff?

If not, can these changes to output be achieved without demanding more from my staff?

![]() If not, are these changes necessary or even possible?

If not, are these changes necessary or even possible?

![]() If so, will I need a new workforce?

If so, will I need a new workforce?

Communication and involvement

At an organizational level, attitudes to communication and involvement will depend heavily on culture. Using the descriptions introduced in Chapter 4:

![]() Power cultures keep information at the centre. Communication takes the form of instructions. Involvement is limited to power-holders.

Power cultures keep information at the centre. Communication takes the form of instructions. Involvement is limited to power-holders.

![]() Task cultures are open. Information and expertise are shared within teams, although there is a tendency to take little or no interest in what other, unrelated teams are doing. Teams will be heavily involved in decisions affecting their own operations. The principal communication problem is likely to be persuading people to take notice of organizational matters which do not affect them directly.

Task cultures are open. Information and expertise are shared within teams, although there is a tendency to take little or no interest in what other, unrelated teams are doing. Teams will be heavily involved in decisions affecting their own operations. The principal communication problem is likely to be persuading people to take notice of organizational matters which do not affect them directly.

![]() Role cultures will have a formal, top-down communication structure. There will be formal communications systems and procedures in place (management briefings, newsletters, noticeboards, electronic mail). Involvement in decisions will be limited, although bureaucracies are increasingly using formal task groups or working parties to increase participation.

Role cultures will have a formal, top-down communication structure. There will be formal communications systems and procedures in place (management briefings, newsletters, noticeboards, electronic mail). Involvement in decisions will be limited, although bureaucracies are increasingly using formal task groups or working parties to increase participation.

![]() Person cultures will see little need for regular communication, since each individual is really running a separate operation. However, decisions which are necessary (for example, upgrading the switchboard, hiring another member of support staff) will be taken jointly. This is, first, because in most person cultures any such decision will have a financial impact on everyone and, secondly, because members of a person culture tend to be distrustful of others’ ability to take sound decisions.

Person cultures will see little need for regular communication, since each individual is really running a separate operation. However, decisions which are necessary (for example, upgrading the switchboard, hiring another member of support staff) will be taken jointly. This is, first, because in most person cultures any such decision will have a financial impact on everyone and, secondly, because members of a person culture tend to be distrustful of others’ ability to take sound decisions.

It is unlikely that you will be able to have much influence on the overall culture of your organization. Nevertheless, in cultures where information is not fully available, it will be helpful to identify those who hold it and to establish relationships with them which will enable you to keep yourself informed.

As far as your own operation is concerned, you have far greater control. As we have pointed out elsewhere in this book, communication increases motivation and the more people are involved in decisions, the more committed they will be to them. The way you communicate is also significant. Regular team and face-to-face briefings are more effective than reliance on the printed word or electronic mail, although some communication will be complex enough to benefit from paper back-up. Also, involving people in decisions should not just happen all of a sudden. Staff involvement in decision-making needs to be a way of life, otherwise they will neither expect, welcome or have the mental agility to cope with it.

Empowerment

Empowerment has been a consistent theme of this book. It involves giving your staff ownership of the work they do, together with the responsibility and authority to carry it out and to seek and implement changes and improvements. Many of the trends and developments in the structure and management of organizations, which were discussed in Chapter 2, are based on the twin foundations of empowerment and delegated responsibility.

However, it would be misleading to claim that empowerment is a painless process, either for managers or for their subordinates. Managers are often appointed because of their technical expertise. They take a pride in their work and rightly set high quality standards. They therefore often suffer from a real concern that the delegation of tasks historically done by the manager will result in a decline in quality. Unfortunately, this view leads to a vicious circle. Because managers fail to delegate, subordinates do not have the opportunity to learn. Because they do not learn, they cannot do the task. Consequently, managers are afraid to delegate to subordinates whom they know lack the necessary skills.

Successful empowerment therefore brings together several techniques and approaches mentioned elsewhere in this book. It depends on:

![]() a willingness to take risks (at least in the first place)

a willingness to take risks (at least in the first place)

![]() careful and detailed monitoring of quality and results (which can be reduced over time)

careful and detailed monitoring of quality and results (which can be reduced over time)

![]() the provision of relevant training

the provision of relevant training

![]() the availability of the manager so that the subordinate can consult and check understanding

the availability of the manager so that the subordinate can consult and check understanding

![]() clear communication of the task and performance standards

clear communication of the task and performance standards

![]() systems for the subordinate to monitor and control their own performance against those standards.

systems for the subordinate to monitor and control their own performance against those standards.

It should be noted that empowerment is not a process of suddenly deciding that your subordinates are capable of more than you used to think, dumping extra tasks on them and walking away. That is abdication, not delegation! Instead, it involves the communication, support and monitoring just summarized.

A final word of warning. Empowerment brings short-term pain for long-term gain. In the short term, it involves extra time, extra effort and extra fear that things will go wrong. In the long term, it will:

![]() free you to spend more time on genuinely managerial work

free you to spend more time on genuinely managerial work

![]() develop your staff

develop your staff

![]() enrich their jobs

enrich their jobs

![]() contribute to the organization's human resource planning by increasing skill levels

contribute to the organization's human resource planning by increasing skill levels

![]() increase job satisfaction.

increase job satisfaction.

CASE STUDY

A small manufacturing business on the outskirts of Birmingham had three directors. They typically worked twelve-hour days, often at weekends as well. Despite their efforts, profits were falling and staff turnover was high. A larger competitor bought them out. The competitor had recognized that the directors were ‘busy fools’ – spending their time doing day-to-day tasks which could have been delegated, but paying no attention to long-term planning, developing markets or financial strategy. Staff were leaving out of boredom.

Developing capability

In an operational context, developing the capability of your staff is no less and no more than ensuring you have the human resources you need to carry out effectively the activities which make up the operation for which you are responsible. It is a far more limited process than the one you will see described in a textbook on staff development, which will look beyond the needs of the current job to examine aspects of career planning and long-term personal development, sometimes even outside the scope of the present employer's business.

The process of developing operational capability involves:

![]() careful analysis of each individual's job to determine the activities which constitute it

careful analysis of each individual's job to determine the activities which constitute it

![]() a prediction of changes to the operation, to identify their impact on the nature of individual jobs

a prediction of changes to the operation, to identify their impact on the nature of individual jobs

![]() the identification of the skills and knowledge needed to carry out the activities which make up the job, both now and in the foreseeable future

the identification of the skills and knowledge needed to carry out the activities which make up the job, both now and in the foreseeable future

![]() a comparison between skills and knowledge required and those possessed by the jobholder

a comparison between skills and knowledge required and those possessed by the jobholder

![]() the design and implementation of a remedial programme to create a match between skills and knowledge required and those possessed

the design and implementation of a remedial programme to create a match between skills and knowledge required and those possessed

![]() monitoring performance after the programme to ensure that the match has been achieved and that new skills and knowledge are being applied successfully.

monitoring performance after the programme to ensure that the match has been achieved and that new skills and knowledge are being applied successfully.

The remedial programme may take the form of:

![]() external training course (although it is important to ensure that its content is genuinely consistent with the individual's needs and that the quality of delivery is adequate)

external training course (although it is important to ensure that its content is genuinely consistent with the individual's needs and that the quality of delivery is adequate)

![]() coaching from the manager

coaching from the manager

![]() side-by-side training from a more experienced colleague (who must, though, have the technical knowledge and skills required, as well as the ability to transfer them)

side-by-side training from a more experienced colleague (who must, though, have the technical knowledge and skills required, as well as the ability to transfer them)

![]() self-study (textbooks, Open Learning, relevant professional articles)

self-study (textbooks, Open Learning, relevant professional articles)

![]() guided experience (made up of introductory coaching or training, followed by on-the-job practice and review).

guided experience (made up of introductory coaching or training, followed by on-the-job practice and review).

As we pointed out earlier, it is a popular misconception to view training and development as outside activities for which the personnel or training function is responsible. Those functions may have an advisory or administrative role, but operations managers are as much responsible for the knowledge and skills of their staff as they are for ensuring the availability of raw materials or the regular maintenance of production machinery.

MANAGING COLLEAGUES

Earlier in this book, we referred to operations management as a horizontal process, with different teams, sections and departments in the organization all representing links in the supply chain, either as customers, suppliers or both. That is the context into which these next two sections fit. Managing colleagues means regular contact with them to ensure that:

![]() they know your needs and expectations of them, if you are the customer

they know your needs and expectations of them, if you are the customer

![]() you know their needs and expectations of you, if you are the supplier

you know their needs and expectations of you, if you are the supplier

![]() or both, if you fit into both categories, as we explained in Chapter 4.

or both, if you fit into both categories, as we explained in Chapter 4.

It also means keeping yourself and them up to date with developments and anticipated changes, so that these can be planned for. It finally means ensuring their confidence in your and your staff's technical or professional competence.

Consulting and informing

If your organization follows the total quality management procedures described earlier in this book, you should have a clear specification of your customers’ requirements, set out in language they can identify with. If not, regular meetings with them will enable you or one of your team to draw up such a specification. This will enable you to determine what their needs are and to track how effectively those needs are being met. This should be an ongoing process, since one of the biggest traps for any operation providing customer service is to assume that what customers want now is what they have wanted in the past. Quantities, quality, speed of output and priorities can and will all change. When you know and have prioritized your customers’ requirements, this may well result in your changing the activities you undertake to meet them. Again, it is a mistake to make those changes without consulting your customers. Use your regular meetings to find out:

![]() Will planned changes result in products and services which satisfy their requirements?

Will planned changes result in products and services which satisfy their requirements?

![]() Are those requirements sufficiently important to the customer to require revisions to your plans?

Are those requirements sufficiently important to the customer to require revisions to your plans?

Similar meetings with your suppliers will enable you to:

![]() communicate to them your requirements and how well they are currently being met

communicate to them your requirements and how well they are currently being met

![]() recommend improvements to the service you are currently receiving

recommend improvements to the service you are currently receiving

![]() notify future changes to your requirements and their implications for suppliers’ activities.

notify future changes to your requirements and their implications for suppliers’ activities.

Meetings with customers and suppliers provide a valuable forum for feedback on performance against standards. However, as we have mentioned elsewhere, they should be regarded as joint problem-solving or continuous improvement activities; not as opportunities to criticize, lay blame or put down.

Developing confidence

One of the manager's key roles with regard to staff is to act as their ambassador. However, it is tempting to overlook this role and, instead, to play the hero by taking personal credit for successes whilst blaming your staff for failure. Instead, when meeting with colleagues, it is important to emphasize the ability and competence of your staff, building trust in them and giving them due credit for the quality and output of your operation. This approach is a far more accurate reflection of a manager's responsibility for staff. After all, if you have recruited, appraised, trained, consulted and communicated with them – and they are still not doing the job effectively – is that not likely to indicate that you, rather than they, are at fault?

MANAGING THE BOSS

The principle of empowerment and delegated responsibility may, at first sight, give the impression that the importance of the boss has been reduced. This is not, in fact, the case. Instead, the boss's role is different, not smaller.

Think back to what was said earlier about managing subordinates. It was suggested that, in an ideal environment, the boss:

![]() informs and consults

informs and consults

![]() monitors performance

monitors performance

![]() advises and supports.

advises and supports.

It is these activities which you should expect from your own boss. However, there is a lot you can do to encourage them.

Representing your people

In several places in this book, I have stressed the value of seeking suggestions and recommendations from your staff for changes or improvements to the operation you manage. However, I have also pointed out that their implementation, even if desirable, may well be outside the limits of your authority. In that case, you will need to seek authorization from your boss. But before doing so, ask yourself the following questions:

![]() Is this initiative genuinely more than I can implement? Limits of authority can be viewed in two ways. From one viewpoint, they specify what you are entitled to do. Seen in that way, any action which is not specifically mentioned is outside your authority. And that is certainly limiting, since whoever drew them up is unlikely to have considered every possible action open to you. Alternatively, limits of authority can be viewed as specifying those things which you are not entitled to do. From that viewpoint, anything which is not specifically excluded is allowed. That gives you much wider scope!

Is this initiative genuinely more than I can implement? Limits of authority can be viewed in two ways. From one viewpoint, they specify what you are entitled to do. Seen in that way, any action which is not specifically mentioned is outside your authority. And that is certainly limiting, since whoever drew them up is unlikely to have considered every possible action open to you. Alternatively, limits of authority can be viewed as specifying those things which you are not entitled to do. From that viewpoint, anything which is not specifically excluded is allowed. That gives you much wider scope!

![]() What is the evidence that change is desirable? If, having reviewed your limits of authority, you are still certain that you need permission from your boss, make sure that change can be justified. In other words: in what ways is your operation not meeting the performance standards set for it? Alternatively: in what ways are current practices, systems or procedures leading to frustration or demotivation amongst your staff?

What is the evidence that change is desirable? If, having reviewed your limits of authority, you are still certain that you need permission from your boss, make sure that change can be justified. In other words: in what ways is your operation not meeting the performance standards set for it? Alternatively: in what ways are current practices, systems or procedures leading to frustration or demotivation amongst your staff?

![]() What benefits will the change bring? What quantifiable performance improvement will the change bring? If the benefits are purely qualitative, why are they worth the effort? If the change requires investment or brings drawbacks, how do these equate with the predicted improvements?

What benefits will the change bring? What quantifiable performance improvement will the change bring? If the benefits are purely qualitative, why are they worth the effort? If the change requires investment or brings drawbacks, how do these equate with the predicted improvements?

![]() How will you measure the improvement? It is rare nowadays that you will be allowed to make changes without measuring their effect. So how will you do this? And how will you know if they have succeeded?

How will you measure the improvement? It is rare nowadays that you will be allowed to make changes without measuring their effect. So how will you do this? And how will you know if they have succeeded?

![]() How will your boss know it has worked? Unless your boss is prepared to trust you absolutely, you will need to be able to show evidence of success. Will current performance measurement provide that evidence, or will you need a different method of performance feedback? Will the evidence come automatically and visibly, or will you need to present it personally?

How will your boss know it has worked? Unless your boss is prepared to trust you absolutely, you will need to be able to show evidence of success. Will current performance measurement provide that evidence, or will you need a different method of performance feedback? Will the evidence come automatically and visibly, or will you need to present it personally?

Remember, too, that your boss should know that the suggested change or improvement has come from your staff. Not only will this demonstrate your ability as a manager to involve your staff in positive action, it will also enable your boss to raise meaningful questions when visiting your operation.

Upward communication

We have already referred to ‘no surprises’ as a central theme of effective management. You may also know from your own experience how easy it is for a manager to become separated from what is happening on the shop floor. Consequently, part of your responsibility to your boss is to provide information about what is happening in your operation. This may relate to:

![]() changes in your team

changes in your team

![]() the performance of the team or of individual team members

the performance of the team or of individual team members

![]() problems you are facing

problems you are facing

![]() the success of initiatives

the success of initiatives

![]() reasons for any deviations from performance standards.

reasons for any deviations from performance standards.

Such information needs to be carefully considered before you share it. Ask yourself:

![]() Is this important enough to mention?

Is this important enough to mention?

![]() How much detail does the boss need?

How much detail does the boss need?

![]() What are the wider implications of what I am about to share?

What are the wider implications of what I am about to share?

![]() What suggestions do I have for dealing with those implications?

What suggestions do I have for dealing with those implications?

Remember that upward communication is an updating process. It should not involve off-loading problems and decisions which are rightly yours onto your boss's shoulders.

Seeking direction

Chapters 2 and 7 explained the importance of operational objectives being derived from and contributing to the achievement of corporate goals. I have also described an ideal system of cascade briefing, whereby everybody in the organization is informed about corporate goals and how their work contributes to them. However, it would be unrealistic to expect that the ideal always applies! As a result, you may well find yourself in a position where you will need to know from your boss:

![]() where the organization is going

where the organization is going

![]() what goals and objectives have been set for your boss

what goals and objectives have been set for your boss

![]() how your operation is expected to contribute to them.

how your operation is expected to contribute to them.

Of course, this information should be reaching you automatically but, in an imperfect world, there may be times when you will need to ask for it.

You may also need to ask for guidance when tackling problems in your operation. These may be:

![]() staff problems

staff problems

![]() customer problems

customer problems

![]() equipment problems

equipment problems

![]() input problems

input problems

![]() systems problems

systems problems

![]() output problems.

output problems.

However, remember our warning against using your boss as a dumping ground for problems you cannot be bothered to solve for yourself. Instead, make sure you have considered in advance:

![]() Is there any need to involve the boss? For example, does the problem have cross-functional or organizational implications?

Is there any need to involve the boss? For example, does the problem have cross-functional or organizational implications?

![]() If so, what alternative solutions can I suggest?

If so, what alternative solutions can I suggest?

You will get a more positive response if you can offer solutions as well as problems:

![]() What will be the consequences of my various suggested solutions?

What will be the consequences of my various suggested solutions?

![]() What inputs do I want from the boss?

What inputs do I want from the boss?

These may be information (‘What budget is available?’) or support (‘I need a temporary member of staff’) or advice (‘Tell me about Fred, I need some help from him but you know him better than I do’).

Fundamental to these three ways of managing the boss is the need for regular meetings, briefings and communication. As you will remember from the description of centralized control in Chapter 2, a major drawback is that management becomes divorced from reality. This section has suggested some ways of keeping the boss out of the ivory tower!

COMPETENCE SELF-ASSESSMENT

1How consistent is your personal style with the culture of your organization?

2What would you prefer your style to be and how would you achieve it?

3How effective is performance appraisal in your organization? How could it be improved?

4What could you do to make more productive use of the appraisal process for your staff?

5How could you improve communication within your team?

6What more could you do to delegate decisions to your team? How could you ensure the success of that increased delegation?

7What more could you do to develop the capability of your staff?

8How could you improve communication with internal customers and suppliers?

9How could you make better use of your boss to improve the performance of your operation?

10What further information does your boss need that you do not currently provide?