CHAPTER 1

Redefining the Competitive Solution

“WE’RE HERE TODAY because we made mistakes,” CEO Rick Wagoner said to the congressional committee. “And because some forces beyond our control have pushed us to the brink.”1

With this simple statement, the leader of General Motors—once the world’s most powerful manufacturer—essentially acknowledged defeat. The company found itself on the edge of disaster; it could remain afloat only if Congress agreed to give it tens of billions of dollars in taxpayer-funded bailouts—and even then its survival was anything but assured.

How could this titan of manufacturing have plunged into such crisis? Sure, the economy had suffered its worst decline in nearly a century. And with it, customers had simply stopped buying. Yet congressional critics addressed Wagoner and his counterparts at Ford and Chrysler with the same criticism voiced by many observers—that before this downturn, Detroit had been in a steady decline for several decades. Now this once dominant corporation—along with much of this country’s automotive industry—teetered at the brink of extinction.

What went wrong with GM and so many other corporations? Have America’s businesses become soft, unable to see the inefficiencies and waste that crept into their operations? Is their challenge as clear as many describe: Find a way to stretch their business further—demand more from workers, speed up processes, apply greater information technology, or outsource more work to lower wage regions? Does the secret to sustaining competitive advantage boil down to finding a better way of cutting costs?

Like so many of America’s other once mighty corporations, it appears that GM had simply fallen victim to its own success. For decades, the company’s unquestioned market leadership gave it little reason to really change. Despite valiant efforts aimed at cutting costs and refining its methods, it seems that the company did so within the confines of its traditional framework for doing business—an approach that proved to be not nearly enough.

The unfortunate reality is that the environment in which this company must operate today looks dramatically different from the one for which its business practices were built nearly a century ago. Despite all the rationalization and finger pointing, this basic disconnect has significantly contributed to its long, dramatic decline. And this is the same challenge that so many of this nation’s corporations and institutions face as well.

Seeing Beyond Stability

GM’s way of doing business traces back to its historic quest early last century to achieve the unthinkable. In 1921 the company’s newly appointed president, Alfred Sloan, set out to break Henry Ford’s iron-clad lock on the automotive industry—one that he held for nearly two decades. Sloan recognized that the enormous efficiencies Ford’s methods generated made competing head-to-head based on low pricing a losing proposition. So Sloan pointed his company in a very different direction—restructuring for a business environment that he sensed had undergone a substantial shift.

With automobiles becoming widely available, Sloan recognized that customers no longer sought rock-bottom pricing as their only consideration. He built a system that moved beyond Ford’s approach of driving down costs by producing huge quantities of nearly identical vehicles. As described in Going Lean, Sloan instead set out to promote a “mass-class” market, which encouraged more people to buy better and better cars—something that Ford’s way of doing business was ill-suited to support.2

GM succeeded in bringing variety and choice within reach of its customers, moving beyond Ford’s presumption of a single product mass market in favor of a strategy of variety. With five lines of vehicles, its offerings could meet a broad range of customer needs and financial capabilities. This strategy succeeded; it ultimately launched GM to dominate what became the largest manufacturing industry in the world.

Sloan managed his company by operating under what he called coordinated control of decentralized operations.3 This meant that the company’s different divisions operated as separate, distinct organizations—designing and producing different lines of vehicles while generating economies of scale through many of their shared resources. But with it came a new burden: the challenge of managing the incredible complexity this created. He needed a way to simplify the problem—to look at each part of the business in the same way, but while preserving the distinct character of each division that would drive his strategy’s success.

What he came up with was a means to track performance by smoothing out short-term fluctuations, essentially measuring based on average production levels, something he called standard volume.4 This greatly simplified oversight, making it easier to relate costs to their driving factors and determine where greater attention was needed, such as where to focus to maximize workforce, inventory, and equipment efficiencies and which managers were performing well relative to forecasted expectations.

It also made it possible to structure the business in a way that gave managers the insights they needed for maintaining efficient use of people, facilities, and equipment without tracking the myriad of details that had made Henry Ford’s methods so complex. Managers no longer focused on the individual details of work as products progressed down the line. Instead, they set their sights on optimizing factories for the averages, which meant turning out huge batches of identical items at a rate that approximated standard volumes. The downside was that efficiencies dropped off precipitously if they had to operate outside of their intended production conditions.

For a long time, this same basic management system thrived; its underlying presumption of steady, predictable demand seemed to closely match the reality of prevailing business conditions. Industries of all types embraced it as the gold standard for managing complex businesses. Today, however, its limitations are becoming increasingly clear, causing an effect that has become quite serious.

To understand why, let us look to an analogous situation that most readers recently experienced in their own lives. The summer of 2008 brought with it a challenge that many people had never before experienced. Gasoline prices rapidly increased, rocketing beyond the dreaded $3-per-gallon threshold and quickly exceeding $4 per gallon. The impact was immediate and crippling, with people everywhere struggling to pay what had become exorbitant amounts simply to fuel their cars.

Americans faced a growing crisis. But what was the cause? Surprisingly, as clear as it seemed, the issue was not simply the high price at the pump. Instead, unaffordable gasoline was merely the visible symptom of a much deeper issue—a dangerous condition that had been quietly developing for years.

The “Steady-State” Trap

Many years ago I began a weekly routine of fueling my car in preparation for my drive to work on the days ahead. I clearly recall the price. Gasoline cost somewhere around a dollar and a quarter per gallon. More than two decades later I distinctly remember noting that not much had changed; the price of gasoline still fell within the dollar-something range.

The presumption of such steady fuel prices factored heavily into the choices I made (not necessarily consciously)—just as it seemed to for many others. The result was significant and widespread: suburbs grew rapidly, as did the size of the typical vehicle. Americans’ average daily commute increased substantially, while trucks and SUVs increasingly filled the highways. It is not hard to see why Americans broke record after record for their consumption of huge quantities of low-cost gasoline. And in doing so, people everywhere locked themselves into lifestyles that were increasingly dependent on continued price stability.

And then everything changed.

When gasoline prices suddenly spiked, most people could do little to change. They still had to drive to work, and they still had to take care of the many obligations that depended on their use of gasoline. The difference was that fuel was no longer inexpensive; drivers everywhere suddenly had to make tough choices in response to their ever-tightening financial circumstances. And the result soon spread to the broader economy.

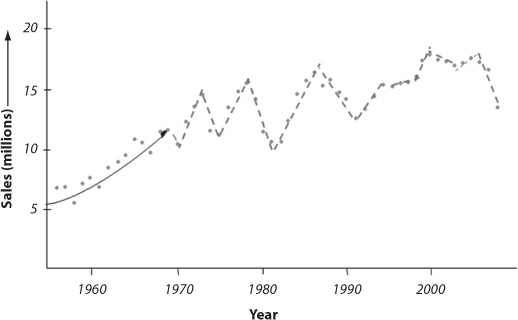

America’s corporations face much the same challenge. Consider the sales trend in the automotive industry, depicted in Figure 1-1. The left side of the graph depicts a smooth and predictable demand pattern in the years following World War II (shown in terms of overall sales)—precisely the environment for which Sloan’s system of management was intended. And for decades, this environment persisted; businesses and institutions everywhere came to operate well within a remarkably narrow range of largely predictable conditions.

Figure 1-1. Automotive Industry Demand Shift

Data Source: Sales from 1965 to 2008: Ward’s Motor Vehicles Facts & Figures 2009, a publication of Ward’s Automotive Group, Southfield, MI USA.

Sales for 1956 to 1964: MVMA Motor Vehicle Facts & Figures, Motor Vehicle Manufacturers Association of the United States, Inc.5

In the early 1970s, the environment abruptly shifted. Unpredictability skyrocketed; customers’ interests began to shift. Businesses that had structured themselves based on a presumption of stability—operating at or near narrowly optimized rates to create great economies of scale to meet precisely forecasted customer needs—suddenly found themselves locked into a way of doing business that was ill-suited for these very different conditions. And each new bout of disruption brought with it the same result: workarounds, disruption, and crisis.

What is particularly striking is how closely this shift correlates to the timeframe in which Detroit’s reputation—along with its market share—began its steep decline. This should have served as a wake-up call for the challenges American producers would face. Yet rather than making a fundamental change to accommodate these dramatically different conditions, they redoubled efforts to stretch their existing product focus and practices a little further—and in doing so achieved the same basic result.

Why does this create such a problem? Going Lean described that such unstable conditions cause substantial internal variation—deviations from intended plans, objectives, or outcomes within traditionally managed organizations built for stability. Variation leads to operational unpredictability, driving the need for workarounds, inventories, and other buffers—waste that draws corporate resources without contributing to creating customer value.

Key Point: What Is Waste?

The late Taiichi Ohno, a recognized architect of the famed Toyota Production System, identified seven forms of waste—excesses that do not add value but draw resources, attention, and create delay and overreaction that promotes more waste.6

1. Overproduction is caused when manufacturers build large quantities of items to maximize economies of scale or build large inventories to buffer against uncertain or changing demands.

2. Waiting is a frequent result of shortages, equipment failures, or other causes of delay from a system suffering the disruptive effects of operational discontinuities.

3. Transportation is one of the more visible forms of waste, including long travel distances that create the potential for delay and the need to handle material several times during delivery or receipt.

4. Processing waste includes extra steps that can creep in over time in dealing with recurring challenges like defects, shortages, and delays due to lagging, disconnected work, or flawed information.

5. Inventory waste is most apparent when manufacturers maintain large quantities of either end items or work-in-progress as a way to bridge value-creating activities whose flow is otherwise disconnected or uncertain.

6. Motion that takes time but does not contribute to the result is wasteful, such as workers searching for tools or “chasing parts” to prevent stoppages from stock-outs.

7. Defects are wasteful on multiple levels. They must be corrected, distracting from operations and causing work that does not create value. Removal of defective parts can cause material shortages on a production line, leading to several other forms of waste (waiting, transportation, motion). Frequent defects create uncertainty, which drives an increase in inventory, another form of waste.

Removing these excesses has become a primary target of today’s cost-conscious managers. Yet waste (along with the variation that can drive its necessity) can be difficult and expensive to control—often it simply recurs once conditions again shift. Moreover, attacking waste directly can backfire, creating localized gains with little impact on the bottom line while compromising firms’ abilities to make more meaningful progress.

The real answer is to implement a solution that helps corporations and institutions better respond to change by restructuring to address lag—the real driver that acts to amplify this variation and drive up loss in customer and corporate value.

Solving the Problem of Lag

A key takeaway from Going Lean is that stable, predictable operating conditions can no longer be the central assumption of American business. What distinguishes truly lean corporations is their very different way of doing business that lets them perform consistently and effectively across a wide range of circumstances.

What exactly do the benchmarks of lean dynamics show? Although the reasons for their success are often explained through their many distinct characteristics and practices, the real answer is much more fundamental. They simply function with far less lag to amplify variation and disruption during changing business circumstances. This lets them quickly adapt, even meeting shifts head-on with innovative solutions—turning what others see as crises into opportunities for advancement.

But what exactly is lag? Lag is delay caused by discontinuities within a system; these act to amplify uncertainty and disruption, impacting the creation of value. To better understand this, think of the lagging response we have all probably faced when we adjust the temperature of our shower, an analogous situation described by MIT professor Peter Senge in his book The Fifth Discipline:

After you turn up the heat, the water remains cold. You receive no response to your action, so you perceive that your act has had no effect. You respond by continuing to turn up the heat. When the hot water finally arrives, a 190-degree water gusher erupts from the faucet. You jump out and turn it back, and, after another delay, it’s frigid again.7

In much the same way, activities that are riddled with large inventories, extended schedules, and long travel distances tend to amplify the effects of uncertainty. The lag these discontinuities create typically goes unnoticed when business remains steady and reliable. However, demand spikes or other sudden shifts ultimately lead to an exaggerated response that creates disruption and delay, causing customer value to rapidly degrade and waste to accumulate.

Consider the reaction to a sudden shift in production within a traditionally managed factory. Individuals performing compartmentalized functions typically have little warning of the changes before they strike. Ad hoc actions take over; workarounds quickly displace tightly synchronized plans, causing disruption to spread up and down the supplier chain. Defects and missed deliveries become rampant, while costs skyrocket. Each unforeseen change brings the need for new workarounds—added inventories and schedule padding, or more people and steps to facilitate expediting—most of which remain in place long after the crisis has passed. Over time these wastes accumulate, drawing ever-increasing resources while adding further to the underlying disconnects that are at the root of this challenge.

Correcting lag that causes this downward spiral of loss is what lean dynamics is all about. This book explains why doing so requires a logical, structured approach that progressively addresses the complex interrelationship between each of the major types of flow: operational, organizational, information, and innovation. The result includes not only achieving the lean outcomes that corporations typically seek to attain—greater quality, innovation, and operational efficiencies—but, most importantly, enabling new business strategies while mitigating the impact of dynamic conditions.

Key Point: Recognizing the Impact of Lag

A central tenet of lean dynamics is to address the lag that creates disruptive outcomes when businesses are subjected to uncertainty and change. This lag can come from disconnects between measurement and outcome, often the result of gaps in the flow of information, work activities, or decisions. The best way to understand the cycle of loss this creates is by thinking of how lag impacts each of the four primary forms of flow.

1. Operational flow is what we often think of when we picture the buildup of value—the progression of those activities involved in transforming products or services from their basic elements to their finished state, delivered into the hands of the customer. For traditional operations, smooth flow comes from precisely synchronizing inventories and activities to meet steady conditions. But when demand suddenly spikes, for instance, inventories can be depleted and schedule buffers overrun, causing shortages that disrupt standardization and synchronization across the business. The underlying disconnects become exposed, but not before amplifying disruption and crisis until operations finally stabilize at a state of loss that can be many times greater than before.

2. Organizational flow is characterized by the smooth progression of decision making by people at all levels and points across the creation of value, which prevents misdirection or overreaction to changes. Organizational structures designed to operate smoothly under normal conditions can quickly shift when crisis strikes. Steep hierarchical structures and strong functional divisions limit individuals’ span of insight, which can amplify disruption when conditions change. The result can be delay followed by misdirection—missing the real issue or correcting problems with a sledgehammer that, with earlier intervention, might have been resolved with only a small tap.

3. Information flow works closely with operational and organizational flow in creating the smooth movement of accurate, timely information to the right people at all levels and points across the creation of value. Information systems seek to improve flow by sharing insights, just as a traffic report alerts drivers about disruptions ahead. Still, the best information can only do so much; a traffic report does little good if there are no exits from the highway. And treating these systems as a stand-alone solution can increase lag.

4. The flow of innovation can be seriously impacted within firms riddled with lag. The introduction of new products or services forces significant changes, which create variation that can disrupt operational flow, particularly where buffers or other lagging factors are present. Corporations tend to avoid this by regulating innovation—extending their existing products and services as long as possible, replacing them only when the loss from making this change is clearly outweighed by the urgent need to generate new sales—something that makes little sense for competing in today’s hypercompetitive global marketplace.

Approaching Lean as a Dynamic Business Solution

Just weeks after the tragedy of September 11, 2001, I arrived at one of the nation’s busiest airports on my way to a conference. I was shocked by what I saw—what was usually a beehive of activity was virtually empty. Besides those who were working there, I saw few other people throughout the entire terminal.

The implications for the U.S. airline industry were enormous. The bottom had completely fallen out—people everywhere simply stopped flying. Most of the airlines responded to the sudden drop in demand the same way. Without passengers to fill their seats, they cancelled flights and grounded as much as a quarter of their fleet. Employees were either furloughed or laid off in droves. Despite taking such drastic measures, all of the major carriers suffered dramatic losses—with many ultimately falling into bankruptcy.

That is, except one.

In the midst of this crisis that shook at the industry’s foundation, Southwest Airlines stood apart. It did not react to the severe downturn and other events following this crisis as its competitors had done. The company kept all of its planes in the air; its employees all remained on the job.8 And it was the only major airline to profit.

How was this possible? Because Southwest Airlines’ way of doing business is not governed by the conventional system described earlier in this chapter. Whereas others had structured their businesses based on maximizing economies of scale—a way of doing business intended for profiting in a steady, predictable mass market—Southwest Airlines had gone a different direction entirely. As the company’s founder and former CEO, Herb Kelleher, put it: “Market share has nothing to do with profitability.”9 Instead, it seems, Southwest focuses on turning out steady value, no matter how conditions change.

By creating a strong connection between what its customers want and its own ability to efficiently operate, the company can quickly adjust to even dramatic changes in its environment. Its steady operations, decision making, information, and even innovation in the face of this and other challenges that followed demonstrate that this company’s approach stands apart from the rest.

Southwest Airlines is not alone; large and small companies (described in Chapter 9) within a range of industries also demonstrate that sustained business excellence demands a different focus. Despite their very different challenges and constraints, these companies display the following set of shared characteristics, which point the way for others to follow:10

Preparing for Uncertainty and Change

Firms that demonstrate lean dynamics consistently display an uncanny preparedness for change—even crisis. Their long histories of overcoming serious challenges seem to have given them a deep recognition that change and uncertainty are here to stay. Those who wish to follow in their path must develop a similar focus: They must develop the ability to thrive across a broad range of circumstances, steadily advancing their capabilities for delivering consistent, ever-increasing customer and corporate value.

But what is value? For these firms the meaning seems quite clear: Value is simply what their customers say it is—even if they continue to change their minds. This means that value is not static in nature; rather, it is constantly evolving, driven by changing technologies, competitive forces, and customer desires.

Satisfying this demand for dynamic value means seeking to understand, and even anticipate, customers’ needs and to satisfy them by constantly developing and rolling out new innovations—not just when existing offerings have run their course. It requires developing the means to consistently accomplish this, even as the business environment shifts. It also means dampening the impact that rolling out new products and services traditionally has on internal operations and suppliers. And it means doing the opposite from traditionally managed firms that insist on dumping their own burdens on the customer. Instead, it involves creating the means to protect customers from some of the turmoil that affects them as a result of difficult times.

A powerful result is the extraordinary degree of customer trust this creates—a deep recognition that these firms will continue to deliver the kinds of solid value that customers really need. Customers at Walmart, for instance, trust that they do not have to shop around to get a better price when they find an item they like. And travelers trust Southwest Airlines to offer the lowest fares and get them to their destinations on time—without the frustration of the hidden fees or reduced services demanded by its major competitors.

This very different focus leads to increased competitiveness even during challenging business conditions—often while others struggle to simply remain viable.

Mitigating Lag Versus Chasing the Problem

Business improvement efforts tend to focus heavily on problem solving—isolating specific areas where issues are most evident and then targeting them for action. Many of today’s lean initiatives begin with an initial exercise to identify waste in organizations’ value streams: finding excesses within the progression of activities required to transform their products or services from their most basic elements and deliver them to the customer. Once they identify excess inventories, processing steps, excessive transportation distances, or anything else that draws resources but does not directly add value to the customer, the typical natural inclination is to target these directly. Yet, too often the result is far less than what they expected.

While there is little doubt that mapping the value stream is an important step toward understanding the problems inherent in traditional management methods, it also creates a dangerous temptation for directly chasing these problems. The simple truth is that the best solutions do not necessarily follow the problem.

For instance, many begin at the end of the line, taking action where disruption accumulates and waste is most evident. But the underlying causes are often complex; correcting it might require making changes that are for less localized (as described in chapter 4). Moreover, what happens when “upstream” activities send disruption down the line to these “leaned out” operations? Disruption reemerges—probably even greater than before—overwhelming activities that no longer have buffers to dampen its effects.

What then should be the focus? Creating a structured solution that addresses the underlying reasons why waste accumulates in the first place. Rather than attempting to advance by using methods founded on the presumption that business will remain stable and predictable over time, those seeking to become lean must fundamentally rebuild their business to address the forces of uncertainty and change head-on.

This means successively addressing the lag that impacts each of the four elements involved in flowing value described earlier, implementing changes in a way that mitigates the dynamic effects that cause waste to accumulate, as will be described in subsequent chapters of this book. The result is farther-reaching benefits that organizations can much more quickly and consistently achieve.

Key Point: Why Chasing the Problems Is Not the Answer

Going Lean described that lean dynamics benchmarks like Toyota, Walmart, and Southwest Airlines did not attain their powerful capabilities by charging straight ahead at visible problems or implementing those initiatives that are most visible on the surface. Instead, they focused on transformational objectives for creating the underlying foundation of smooth flow on which their success depends (described in Chapter 6). Some important considerations for applying this focus include:

![]() Understand why changes are needed. Because making changes to processes can be expensive and disruptive, understanding the bottom-line rationale and larger benefit is critical prior to embarking on waste reduction, standardization, or other process streamlining activities.

Understand why changes are needed. Because making changes to processes can be expensive and disruptive, understanding the bottom-line rationale and larger benefit is critical prior to embarking on waste reduction, standardization, or other process streamlining activities.

![]() Focus on transformation rather than following the problems. To avoid targeting waste reduction without a central focus, a few simple questions should be considered: Are proposed efforts simply a way of stretching the current approach to doing business a little further? Is this the right sequence for these activities (per the framework described in Chapter 6)? Is this the best way for the business to spend its time, attention, and resources?

Focus on transformation rather than following the problems. To avoid targeting waste reduction without a central focus, a few simple questions should be considered: Are proposed efforts simply a way of stretching the current approach to doing business a little further? Is this the right sequence for these activities (per the framework described in Chapter 6)? Is this the best way for the business to spend its time, attention, and resources?

![]() Insist on dynamic transformation. Rather than simply optimizing for steady-state conditions, efforts should focus on identifying and addressing disconnects in flow and the lag they create. This can help ensure that dynamic effects that create disruption and loss are being reduced.

Insist on dynamic transformation. Rather than simply optimizing for steady-state conditions, efforts should focus on identifying and addressing disconnects in flow and the lag they create. This can help ensure that dynamic effects that create disruption and loss are being reduced.

![]() Relate all lean efforts to bottom-line metrics. Too often programs aimed at discrete waste reductions do not take into account the great costs of generating them or the inadvertent shell game in which some areas gain at the expense of others (further explained in Chapter 6).

Relate all lean efforts to bottom-line metrics. Too often programs aimed at discrete waste reductions do not take into account the great costs of generating them or the inadvertent shell game in which some areas gain at the expense of others (further explained in Chapter 6).

Promoting Dynamic Stability

How can corporations and institutions consistently meet or exceed customers’ demand for dynamic value amid the challenging circumstances facing businesses today? Create a fundamentally different structure—one that is dynamically stable—that diminishes disruption to operations, decision making, information, and innovation in the face of changes or disruptions.

Traditionally managed companies tend to be dynamically unstable, meaning that they perform poorly when pressed to operate outside of their intended range of conditions. As described in Going Lean, the result is much like pushing a boulder up a hill: They must redirect enormous resources just to keep from falling backward. Firms demonstrating lean dynamics instead create a structure that accommodates a much broader range of circumstances, essentially flattening the hill—dampening variation before it has a chance to build. This lets workers and managers maintain their focus despite enormous shifts, rather than fall backward, as they otherwise might, with every new challenge.

How is this possible? Toyota, for instance, does this by deliberately mixing together and varying the types and quantities of items it makes on a given production line—producing each in small lot sizes that more closely approximate the rate of customer demand. This dramatically reduces demand uncertainty (which is instead amplified by traditional methods). Toyota’s approach of co-producing families of items (groupings of items that share common characteristics so it is possible to seamlessly shift from processing one to the next) creates a mechanism for dampening the variation that changing conditions promote (an effect described in Chapter 4).

The result is creating the ability to dampen out the variation that traditionally results from sudden shifts, instead promoting the ability to sustain a consistent focus even during some of the most challenging circumstances. This helps these companies not only survive the downturns, but continue to advance innovation and pursue opportunities to create new value.

Challenging the “Culture of Workarounds”

American corporations and institutions are tremendously adept at dealing with crises. Their ability to overcome adversity and respond quickly when conditions do not turn out as planned has become essential to traditional business management methods. Rising to the top requires a strong capacity to make last-minute saves, like a football player who makes a diving catch in the end zone, for results that are immediate and visible. Yet such a culture runs counter to creating the consistent, dynamic value that is so critical to competing today.

Those striving to go lean must seek to create far greater consistency in their activities, designing their progression of work such that it can remain stable across the entire range of circumstances in which they operate. Lean capabilities, rather than individual heroics, mitigates the need for quick fixes; this can drive the capacity to sustain the rigorous and responsive progression of work, decision making, information, and innovation without the need for resorting to unplanned work, extra steps, or other wasteful measures in response to changing conditions. Achieving such consistency, however, takes more than restructuring the mechanical aspects of a business; it requires shifting the underlying culture that drives workarounds to flourish.

Changing this imbedded culture represents a central challenge for those implementing lean dynamics. People across the enterprise—managers, workers, and even suppliers—must understand that the most important part of the job is no longer last-minute heroics; instead, they must focus on preventing crises from occurring in the first place. Together personnel must create approaches for continuously improving the dynamic stability of the company and identify ways to forge ahead with new forms of value for the customer and corporation—regardless of the challenging conditions they might face.

Recognizing the Need for Transformation

Jack Welch observed that “only satisfied customers can give people job security. Not companies.”11 Nowhere is this clearer today than in America’s automobile industry. For decades, its workforce and management focused on mitigating internal risks, seeking concessions that would strengthen their respective objectives for workforce protections and controlling labor costs. But all the while they missed the much greater risk—that building agreements based on past measures of success would only further entrench a way of doing business that was poorly suited to meeting the changing needs of their customers.

And now each side risks losing it all.

Firms and institutions must come to see that the real risk lies not in departing from what has become familiar but in sticking with what worked in the past. They must accept that the world is a much different place than it was when their traditional way of doing business was first created. Uncertainty and change have become the norm; customers today expect much more, and in the age of global business and the Internet, they have the means to get it. Conditions have become much more severe; case after case demonstrates the perils of standing still when challenges continue to evolve.

Despite its challenges, sustained excellence in this more severe business environment is possible—but only for those who are willing to step away from their false sense of security and embrace the principles that distinguish lean dynamics.

The critical challenge for most firms is not only to overcome their preconceived notions and recognize what going lean is really all about but also to translate it, beyond principles, into rapid, visible results and practices that address the real issues and challenges they face. Unfortunately, this is where lean efforts very often fall short. It is far easier to minimize meaningful principles in favor of slogans and simplistic plans that can be quickly grasped but do not build the needed foundation for sustained progress.

The next chapter describes some important steps to building a foundation and creating a case for a solid direction that will win deep-rooted support from everyone across the organization who will contribute. For this to succeed, however, each must clearly understand what must be done and why he or she must change in a way that is meaningful and actionable.

Key Point: Major Distinctions of a Lean Dynamics Approach

Lean dynamics recognizes that traditional methods designed for turning out value based on a presumption of stability and predictability have become stretched to their limits in today’s environment of uncertainty and change. Value is dynamic; it is what customers say it is—even if they keep changing their minds. Lean dynamics is about adapting to this changing value and consistently driving efficiency, quality, and innovation across a wide range of conditions.

![]() Traditional methods build in disconnects by design—gaps within operations, decision making, information, and innovation that together amplify variation and increase its disruptive effects. This lag typically goes unnoticed when forecasts prove steady and reliable. However, demand spikes or other sudden shifts ultimately lead to an exaggerated response when subjected to uncertainty and change.

Traditional methods build in disconnects by design—gaps within operations, decision making, information, and innovation that together amplify variation and increase its disruptive effects. This lag typically goes unnoticed when forecasts prove steady and reliable. However, demand spikes or other sudden shifts ultimately lead to an exaggerated response when subjected to uncertainty and change.

![]() The greater a business or an institution’s lag, the greater the potential to overreact to changes, amplifying internal variation and increasing disruptive outcomes. This lag can come from a range of sources: from disconnects between measurement and outcome to discontinuous flow of information, operational steps, and decision making.

The greater a business or an institution’s lag, the greater the potential to overreact to changes, amplifying internal variation and increasing disruptive outcomes. This lag can come from a range of sources: from disconnects between measurement and outcome to discontinuous flow of information, operational steps, and decision making.

![]() The best way to find lag is to identify its adverse outcomes, the most visible of which is the accumulation of waste. Waste is often the result of operating in dynamic conditions but with a management system optimized for stability.

The best way to find lag is to identify its adverse outcomes, the most visible of which is the accumulation of waste. Waste is often the result of operating in dynamic conditions but with a management system optimized for stability.

![]() The bottom-line result is a loss in value. Loss is the portion of the value that the business or institution must expend in order to turn out this value—including waste. Reducing waste is therefore critical to maximizing bottom-line value.

The bottom-line result is a loss in value. Loss is the portion of the value that the business or institution must expend in order to turn out this value—including waste. Reducing waste is therefore critical to maximizing bottom-line value.

![]() Going lean means more than addressing discrete elements of waste, each of which can have an uncertain impact on the bottom line. It means broadly minimizing loss—not only for existing circumstances but across the wide range of uncertain and changing conditions firms and institutions increasingly face as part of doing business within today’s dynamic conditions.

Going lean means more than addressing discrete elements of waste, each of which can have an uncertain impact on the bottom line. It means broadly minimizing loss—not only for existing circumstances but across the wide range of uncertain and changing conditions firms and institutions increasingly face as part of doing business within today’s dynamic conditions.

The result is the strong, steady value—the ability to consistently innovate, profit, and advance into new markets within even the most severe conditions—that marks the benchmark of lean dynamics.