CHAPTER 6

Targeting Transformation

FOR MORE THAN half a century Dr. Shigeo Shingo has been acknowledged as an engineering genius for his contributions in creating and disseminating the benefits of the Toyota Production System. Today, with a major award bearing his name, this recognition seems destined to continue.1 Yet, despite all of the fanfare, his methods seem generally misunderstood; the general focus of many lean initiatives today appears to be drifting away from the underlying intent of his teachings.

Shingo’s attention was not so much on addressing widespread inefficiencies; instead, his focus seemed to be on advancing key elements making possible deeper aspects of lean transformation. One major emphasis was on speeding equipment changeovers—he took aim at slashing the time it took to shift equipment from producing one part to begin producing another.

Equipment changeover was clearly a significant constraint to production activities at the time; automobile manufacturers routinely took an entire day to remove and replace the dies used in stamping body panels. This drove factories to operate using extended production runs to absorb the cost of this downtime, producing large batches of identical items before changing over again—economic quantities they sent to storage until needed. Shingo focused on slashing changeover times (in conjunction with managing by product family, as described in Chapter 4) as a means to drive down the need for these large batch sizes and permit factories to produce in quantities that more closely matched actual demands.

Going Lean described how this very different focus transformed Toyota’s production approach; slashing changeover times was instrumental to creating such recognizable lean benefits as quicker deliveries, lower inventories, higher quality (in part from reduced changeover errors), greater productivity due to less downtime for people and equipment, and greater flexibility for meeting changing customer needs.

Central to making this approach work was Toyota’s relentless pursuit of waste reduction—not as a general means for cutting costs (as it is often applied today), but as a targeted emphasis to support key shifts like reduced changeover times.2 By restructuring setup activities and eliminating excesses of all types, Toyota was ultimately able to cut its major setups from several hours to around three minutes.3

Creating Solutions, Not Chasing Problems

Today, waste reduction seems to have become the mantra of much of the business literature, as evidenced by the proliferation of problem-solving tools that corporations and institutions hasten to adopt. Corporations and institutions are quick to embrace this—perhaps because of its intuitive benefit to how they operate today. But, as we have seen, making real progress comes from applying these techniques not to target a specific problem or desired outcome but to create transformational shifts for progressively advancing in maturity.

This realization first hit me more than a decade ago while I searched for lessons during my study of manufacturing improvement methods for the Joint Strike Fighter Program. On the surface, the results in applying improvements ranging from lean to Six Sigma techniques seemed broadly successful. Most slashed huge amounts of waste from activities ranging from materials management through assembly; production times were down nearly across the board, as were inventory levels. And for many of the participants, improvements were dramatic—as much as 67 and 80 percent, respectively.4

Yet, in spite of their success in waste reduction, only a small number demonstrated as significant of results when it came to reducing their bottom-line costs. Although things seemed to be moving in the right direction, these discrete fixes did not add up to the expected results.

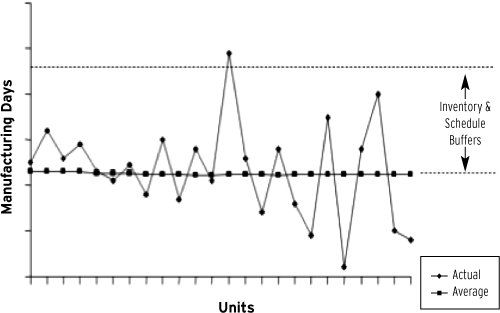

A handful of factories stood apart. They went beyond implementing lean tools as tactics aimed at correcting discrete work-stations or narrowly defined value streams—beyond the targeted problem solving that seems typical of improvement efforts. Instead, they advanced by progressively addressing an underlying condition that affected their overall results: their cycle time variation, or the deviations in time it took to assemble each successive unit off the line (depicted in Figure 3-1). Doing this, it turned out, was the key to attaining powerful, bottom-line cost savings.

Figure 6-1 illustrates the severe state of internal variation my study team found affected one factory (a result that does not seem to be atypical in this industry). The chart depicts its problem: substantial cycle time variation—wide swings in the time it took to build each successive unit, deviating as much as 30 percent from the average.

Figure 6-1. Example of Cycle Time Variation in Aerospace5

Why is this important? The study showed that the turmoil this represents undermines a factory’s ability to operate efficiently—driving up inventories and extending production schedules, compromising operational predictability. As described in Chapter 1, workarounds to standard procedures create a greater potential for errors, requiring additional inspections and bookkeeping to ensure critical defects do not escape (particularly critical in producing aircraft because of the criticality of protecting flight safety). And the uncertainty this causes has an amplifying effect up and down the line, impacting scheduling or causing workarounds in the many shops and suppliers feeding the component items that support these operations.

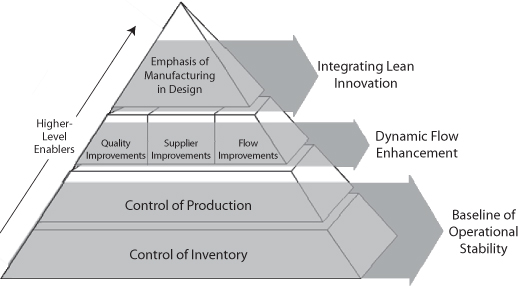

Those companies that had achieved the greatest results stood out in that they made great progress in addressing this cycle time variation—going beyond applying lean methods as part of a scattershot approach to creating tactical fixes, instead stabilizing their operations by first improving their management of basic elements like production and inventory control capabilities. Only after freeing up the basic bottlenecks that choked the progression of their activities did the more recognizable lean tools (e.g., statistical measurement tools, value stream realignment, advanced supplier relationships, or enhanced product designs) generate substantial results. Taking actions that progressively addressed this underlying driver for real improvement led to the most significant bottom-line savings.6

Knowingly or not, these facilities had come up with a powerful solution addressing a core transformational focus—creating a baseline for stability before advancing to more recognizable lean practices by successively addressing the greatest drivers for mitigating uncertainty and disruption, a critical challenge facing their business. Their structured advancement demonstrated the potential to save as much as 25 percent of the cost of producing an aircraft. Perhaps more importantly, their results showed that for implementing lean activities, a natural progression does exist.7

Identifying Focal Points for Transformation

We have seen that advancing in lean maturity takes breaking objectives into manageable focal points and addressing them through a structured progression of activities. For aerospace manufacturing, mitigating cycle time variation and creating a baseline for predictable operational flow proved to be the essential initial focal point.

But how can companies attain this? My research identified the need for a structured approach consisting of a progression of actions that first create a baseline of stability (such as improving inventory accuracy and production control to make the right materials available when needed), reducing workarounds, and permitting more recognizable lean tools to become most productive (as shown in Figure 6-2).

This same general structure can point the way for other industries to progressively address core challenges they must overcome to advance in lean maturity. A hospital, for instance, might begin by identifying the core drivers it must address—substantial factors like infections or unpredictable patient loading that have the greatest impact on short- and long-term objectives for optimizing patient care. Developing a progressive structure for addressing immediate challenges can build the stable foundation needed to progressively move forward with actions offering increasing benefits.

After creating a more stable foundation, the next activities might concentrate on key dynamic drivers affecting their value creation; perhaps addressing long supplier lead times that might cause little impact during stable demand, but create enormous challenges when conditions suddenly shift. Actions that begin with more tactical measures like collaborating to hold long-lead materials or components (intended as a temporary means for addressing key drivers of operational lag, described in Chapter 7) might advance to more dynamic solutions at this phase. Assembling cross-functional action teams responsible for progressively fostering an expanded shift (described in Chapter 5) can promote solutions such as combining elements into product families to smooth out variation and broadly address these challenges. The structure this provides for understanding the nature of value from end to end offers a powerful platform to define and manage follow-on activities and create significant impact on these core areas, optimizing progress while lowering resistance to change and progressively addressing the steepness of their value curve.

Figure 6-2. A Hierarchy for Progressing with Lean Implementation8

Adopting such a structure for addressing specifically defined focal points creates a powerful means for breaking from the tool-based, problem-solving mindset that leads to fragmented results and acts as a barrier to advancing in lean maturity. But for many managers and executives, this application can be difficult, because it means rethinking actions and fully thinking through the underlying changes they intend to achieve before launching into lean improvement projects.

Leading with Metrics

One of the greatest challenges in implementing business transformation efforts is determining a clear way to measure results. Many organizations progress using outdated performance measures; despite identifying a new focus aimed at better supporting customers, they might cling to internally focused metrics that measure average process performance—causing well-intentioned lean efforts to end up improving internal efficiencies without a clear way of tracing them to the objective of maximizing product value that they set out to achieve.

Perhaps the root of the problem is that most of today’s improvement programs quickly shift attention away from any tangible way of tracking value. After becoming sold on the need to apply information technology, business process reengineering, or Lean Six Sigma, organizations quickly seek to identify and implement improvements to processing steps. Yet, in complex operations, it can be difficult to relate processing changes to tangible improvements in customer value. This represents a fundamental source of lag—one that must be corrected as an integral part of shifting to a leaner way of doing business.

Going Lean introduced a concept for more specifically measuring value: using the value curve to assess a business’s or an institution’s creation of products and services in response to changing customer demands and business conditions. This proved to be a powerful measure for gauging companies’ bottom-line performance, distinguishing lean organizations from the others. It stands to reason that this same approach can be applied to measuring performance for individual products at different stages of value creation (applied to their major increments of value, described in Chapter 4), or even as a means for gauging responsiveness to the needs of specific customers (mapping customer-specific value curves). This offers a direct means for assessing a company’s (or its suppliers’) effectiveness in improving value at various stages in its creation, eliminating a key source of lag in tracking progress with lean improvement initiatives.

However, it is also important to identify interim checkpoints to keep improvement efforts from falling off course along the way. These offer the means to track incremental progress, sustaining focus and enthusiasm throughout what might otherwise seem to be the endless pursuit of an elusive goal.

But what should constitute such checkpoints? To answer this, consider the challenge of building a cross-country railroad. A straight-line approach to assessing progress across a three-dimensional landscape does not begin to describe reality; it would miss all of the hidden effort that goes into accommodating a challenging terrain. Similarly, much of the progress toward implementing lean dynamics goes beyond what is seen on the surface; much of what is done goes to building a foundation for overcoming business obstacles rather than addressing them head-on. Measurements must therefore focus on advancing not only those results that can be clearly seen but also the less-visible elements involved in creating an optimal solution.

Cycle time variation (described earlier in this chapter) offers one such checkpoint. As a key indication of flow disruption, high cycle time variation points to areas within the value-added map where lag is likely to be significant—areas where taking action can create the greatest benefit. Thus, it can serve as a metric to help identify transformational focal points and track progress toward improvement (in conjunction with such traditional measures as inventories and cycle time, which together proved in my aerospace study to be the indicator of greatest success in addressing loss).

Beginning with strong, well-designed metrics is a critical follow-on to the dynamic value assessment. Together they bring greater consistency and clarity to a direction that might otherwise not be so evident within the fragmented structure within which most must begin. This can help managers reach forward in a consistent direction even as their span of insight continues to grow, mitigating the need for them to mandate arbitrary quotas that do not necessarily contribute to intended results.

Key Point: The Illuminating

Nature of Metrics

There is tremendous wisdom in the old expression What you measure is what you get. Organizations are often amazed by what they can achieve by using metrics to shine a light on what is truly important.

![]() Keep it simple. Often businesses create too many metrics, overwhelming managers with information, with the result that none stands out as important. Creating a few that focus on the top-level vision (relating directly to the value curve), with others that tie this directly to the focal points for localized initiatives (such as cycle time variation) supported by specific supporting objectives (e.g., lead times, cost, and quality), can help create a greater focus on what is important for substantial progress.

Keep it simple. Often businesses create too many metrics, overwhelming managers with information, with the result that none stands out as important. Creating a few that focus on the top-level vision (relating directly to the value curve), with others that tie this directly to the focal points for localized initiatives (such as cycle time variation) supported by specific supporting objectives (e.g., lead times, cost, and quality), can help create a greater focus on what is important for substantial progress.

![]() Balance bottom-line metrics. Focusing on several interrelated metrics at once helps avoid results that resemble what happens when one side of a balloon is squeezed—things tighten up where attention is focused but not without causing things to simply shift to other areas that are not tightly controlled.

Balance bottom-line metrics. Focusing on several interrelated metrics at once helps avoid results that resemble what happens when one side of a balloon is squeezed—things tighten up where attention is focused but not without causing things to simply shift to other areas that are not tightly controlled.

![]() Measure at all levels within the organization. Delegating responsibility for measurement and oversight to those who are closest to the action is critical to minimizing complexity. Not only does this contribute to expanding the work-force’s span of insight, but it reduces the complexity of coordinating information and enables decision making at the appropriate levels in the organization—key factors in mitigating lag.

Measure at all levels within the organization. Delegating responsibility for measurement and oversight to those who are closest to the action is critical to minimizing complexity. Not only does this contribute to expanding the work-force’s span of insight, but it reduces the complexity of coordinating information and enables decision making at the appropriate levels in the organization—key factors in mitigating lag.

![]() Track interim conditions that support bottom-line metrics. Tracking is essential for multiphased projects, ensuring that the workforce understands that even the less visible advances are essential to the progression to lean maturity.

Track interim conditions that support bottom-line metrics. Tracking is essential for multiphased projects, ensuring that the workforce understands that even the less visible advances are essential to the progression to lean maturity.

![]() Create execution transparency. Metrics must relate to bottom-line results, ensuring that changes create real improvements for both the customer and the corporation.

Create execution transparency. Metrics must relate to bottom-line results, ensuring that changes create real improvements for both the customer and the corporation.

Transforming from the Top

Most business management books will tell you that real transformation must begin by attaining support from top management for what lies ahead. But too often, support seems superficial; after the initial sales pitch, management might agree to hire consultants to manage the tasks involved, enabling themselves to move on to more pressing matters.

Yet, it is hard to imagine matters more worthy of executives’ attention than guiding the bottom-up transformation of their businesses.

Perhaps the reason so many managers disengage from the details is the belief that such efforts can be managed as so many operational tasks are today: as standardized activities whose benefits will inevitably reach the bottom line. We have seen, however, that implementing lean is far from standardized; businesses and institutions must develop their own strategies to fill their existing gaps, creating a pathway that suits their unique challenges, constraints, strategies, and values. These cannot come from hired consultants, or even from middle managers; choosing the direction at critical junctures must come straight from the top.

Those at the highest levels of management must therefore lead in developing a deliberately planned, well-constructed, and tightly measured progression of activities to advance their organization in lean maturity. Their continued engagement is critical for maneuvering its complex, changing pathways, responding to the evolving insights and changing conditions that will emerge during the course of its implementation.

As we saw in Chapter 5, while leadership is critical, the workforce is central to identifying and executing the transformational shifts necessary for going lean. Leaders must engage and empower their people, beginning with their middle managers, not just superficially, but in a way that lets them truly become a core part of the new solution.

Breaking Through the Hierarchy

Perhaps the greatest role that managers must serve is creating the right culture to support real transformation. They must lead the way by clearly and consistently communicating the reasons for the shift, reiterating core points from the case for change, and continually reaching out to reassure people who are undoubtedly concerned about their future with the corporation. What is perhaps most important, however, is demonstrating that all staff are part of this solution—that management, too, is affected—and that this will create opportunities for the business and its people.

Management functions, like production activities, tend to be split into specific areas of responsibility. This creates an emphasis that tends to be introspective; managers might focus attention on improving activities that appear to make things work better but in reality add no meaningful benefit to the bottom line. Such a fragmented approach tends to reinforce existing disconnects; it can increase lag, actually undermining a company’s or an institution’s progress toward creating a lean solution.

What can be done? Organizations and institutions can embrace the decentralization principles of lean dynamics (described in Chapter 5) and break through natural divisions within the management hierarchy to promote decision making that will be much less bureaucratic to better support the goal of creating smooth organizational flow. Breaking down a steep hierarchy and delegating more authority downward is important to streamlining decision making and simplifying information flow, each of which is critical to speeding the flow of solutions and ideas.

For decades, experts have understood the need for making this shift in organizational structure a core part of going lean “so that job responsibility, information linkages, and reporting relationships will not hamper its progress.”9 Yet making such a shift is far from trivial; it takes breaking down traditional organizational barriers and establishing an action team with improved linkages to facilitate the deeper analysis and innovation needed for crafting farther-reaching solutions. And this requires reaching an understanding with the leaders of each of the affected divisions, who must accept that they must lose top employees to another team.

A first step toward restructuring might be creating a steering committee—a decision-making forum to include from the outset all major stakeholders across the enterprise in structuring for the lean transformation. This serves as a means to expand decision makers’ insight, growing their buy-in and understanding as the movement continues to mature. This can be vital to making the organizational shifts that are so critical to driving real transformation, such as populating improvement teams with the right resources and making process changes that will likely span the traditional boundaries of many parts of the organization. It also brings top experts with the broadest span of insight together to validate its direction at major decision points along the way.

The way in which this committee is structured is particularly important; adequate inclusion and ground rules can make the difference between creating great benefit or serious liability. Furthermore, corporations and institutions should consider bringing in labor at the outset; at some point along the way, they might consider including suppliers and, after progressing past the tactical to the dynamic levels of maturity, might also consider bringing in customers once a basic level of stability has been achieved.

Another important aspect for the committee to consider is how to encourage employee participation in lean dynamics efforts. For instance, it is important to create organizational mechanisms that make clear that a lean dynamics role is not a path to obscurity, but one that will lead the way to future opportunities. This is critical if the best and the brightest are to be drawn away from traditional, prestigious areas of specialty with known career paths.

Embracing Criticism

Some lean experts indicate that one of the greatest barriers to going lean is the widespread resistance of middle management. They suggest that these managers simply do not want their jobs changed; others say that they need more training. Almost universally, the problem is presumed to rest with those who resist—that lack of real progress is somehow their fault because they simply oppose change.

But when so many front-line leaders raise a concern, wouldn’t it make sense to first understand the basis for their concerns before writing them off ? This is where top leadership has the opportunity to become engaged; rather than discouraging important insights, they can encourage feedback from their cadre of middle managers, whose clearer vantage points might offer valuable insights that can improve their direction or keep their efforts from stumbling.

This is precisely what I tried to do. As I traveled the country following the release of Going Lean, I spoke with many individuals who expressed real concern about what they had been asked to do. They seemed to have valid concerns—for one, that implementing lean at one facility could mean something strikingly different at another. Most convinced me they had their organizations’ best interests in mind and seemed passionate about driving change—but for all this time, effort, and expense, he or she demanded real improvement, without creating new problems.

Some were charged with searching out anything that could be claimed as “lean,” filling out spreadsheets with as many “savings” as they could to prove the program’s success. Others cringed as lean teams established rules that eliminated meetings or other activities deemed “wasteful” because they did not directly impact the customer. While not all examples were this extreme, it was not hard to see why individuals involved in this had become frustrated, and I could not help but share in their concern.

Why, then, wouldn’t their leaders listen? If a central part of going lean is embracing the insights of the workforce, wouldn’t these companies want to learn as much as they could from their front-line managers, individuals entrusted with making things happen that really matter?

Years ago I was shocked by the seemingly counterintuitive way a manager dealt with a different sort of critical feedback, expressing outright excitement when a customer survey showed a sharp increase in negative feedback. How could he see this as good news? The answer was simple. In the past, he explained, customers had no reason to believe that their concerns would be acted on. Subsequently, however, his organization had changed; it began taking deliberate, visible action to address their complaints. Since customers could now see real evidence of interest, they knew their input would make a difference. The bottom line was that they now cared enough to explain what they really thought.

This is a critical tenet in transforming to lean; stakeholders of all sorts, inside and outside of the organization, must feel free to give their insights. They must come to care enough to do so because they believe that their feedback will be valued. For an approach founded on the contributions of its people, this should be the cornerstone for action. Yet it is perhaps the most frequent failure, causing well-intentioned people with solid insights to hold their tongues rather than risk severe backlash.

So, in a way, it appears that middle management resistance is more of an outcome of poor guidance and leadership than the problem itself. How then should leaders respond? They should listen to their managers who are particularly well positioned to recognize any disconnects between objectives and measurements. They must look for ways to include their managers and encourage them to offer insights and to incorporate those insights into their methodologies and solutions in meaningful ways.

Rather than discouraging them, a key focus should be enabling them, looking for ways to expand their spans of insight—helping them to create solutions truly aimed at transforming end-to-end value creation for the corporation and the customer.

Key Point: Selecting Transformational

Focal Points

A central driver to lean success is selecting the right focal point for transformation. Yet selecting these focal points depends on reaching beyond the narrow insights of managers limited by compartmentalized organizations. These focal points must reflect not only what is truly important to the business but the effect of these challenges on the customer.

Consider a common area of focus today: speeding up contract awards and creating long-term supplier arrangements. Each brings intuitive benefits to the procurement organization that will likely lead these efforts, slashing its workload and increasing its measures of productivity. But for a large organization with vast numbers of supplied items to address, where should it begin? A common recommendation is to concentrate on the much smaller number of items that analysis often shows makes up a large percentage of the total volume. Focusing on these, it seems, will naturally yield the greatest benefits to the customer and the corporation because of their contribution to sales volume.

From a lean dynamics perspective, however, their attention to these high sales volume items might not be the best avenue to cost reduction and customer results.

Think of organizations like the one described in Chapter 4, charged with supplying customers with critical items whose demand is low and uncertain but whose impact can be enormous. As described in the case study, demand uncertainty makes it difficult to stock the right number of items to meet their customers’ needs, and their enormous lead times mean that incorrect forecasts will substantially impact their customers. By taking aim at this tremendous source of lag and uncertainty (e.g., restructuring to manage these items as product families for the variation smoothing effect illustrated in Figure 4-1), they can substantially increase predictability, while cutting lead times. The result can be twofold: slashing costs while driving up the ability to respond to customer needs.

Conversely, even substantial improvements for items whose demand is already fairly stable might have only a limited effect on their inventories (which are already fairly small and deterministic); since these tend to be widely available, their risk of stock-outs is already low. Moreover, while their individual sales quantity may be high, they might represent only a fraction of the range of items their customers need. Thus, from a product support standpoint, even a positive result can be far smaller when viewed from the perspective of the customers’ needs.

Analysis of customer orders can reveal other potential focal points. For example, some important customers may disproportionately demand very short response times, stressing the company’s ability to respond. Collaborating with these customers might give some insight into the reasons for such orders, perhaps reducing the high costs associated with urgent shipping (which can be an extraordinary cost driver). And, as described in Chapter 9, the resulting trust that this relationship will likely build can lead to further opportunities for new business down the line.

The difference seems clear. Rather than focusing on first-level issues that might produce limited results and have little impact on the customer, businesses and institutions can direct their efforts toward addressing greater sources of lag to produce greater impact on the customer and create the opportunity for much greater cost savings across a wide range of conditions.