CHAPTER 4

Building a New Foundation

IN 1903, mechanical engineer Frederick Winslow Taylor proposed a business philosophy that promised to unleash new levels of productivity. His principles of scientific management held that dividing workers’ individual tasks into their smallest components, coupled with their strict standardization and control, would permit great advances in productivity. For decades, this clear division between the realms of performing work and its management served as the basis for business management, leading the way for unprecedented increases in productivity.1

Managers everywhere have come to realize the shortfalls of Taylor’s principles, particularly in today’s environment, in which workers’ knowledge and broader participation have become more valued. A focus on managing work as a collection of isolated activities undermines workers’ insight into the contribution of their efforts to bottom-line value; applying rigid top-down controls to regulate the details of day-to-day activities discourages individual creativity.

Still, today’s business improvement methods can seem to drift down this same path.

It is not hard, for instance, to find consultants armed with process maps and sticky paper pads scrutinizing time and motion in a manner that, to the casual observer, can look much the same as that of Taylor’s early efficiency experts—speeding work steps and moving activities closer together in order to shave precious seconds from production. Why do companies accept this? The short-term benefits can seem appealing. Companies and institutions have reported significant cost savings, a tantalizing prospect to those struggling with the challenges of today’s economic downturn.

Consider the approach employed by Starbucks, perhaps the most recognizable name in high-end coffee retail. The company purportedly has sent its vice president for lean, along with a ten-person team, from region to region with a focus that seems simple and clear: Slash the time that workers spend in unproductive motion. The approach? Teach managers to overcome waste by challenging them to assemble and then break down a Mr. Potato Head toy in less than forty-five seconds.2

Yet, for a business that seeks to capture premium prices for distinctive, hand-crafted products, it is hard to understand how the apparent objective of trimming a couple of seconds of wait time—an improvement that few customers are likely to notice—is reason to declare success. And these methods seem to be alienating at least some within its workforce—the very people upon whom going lean most depends.3

Somehow the real goal seems to have been lost along the way. Going lean should mean far more than applying process improvement tools and techniques to stretch traditional methods a little farther; it should accomplish more than simply trimming a few seconds of time or cutting an increment of inventory. Instead, it should be about adopting an entirely different philosophy that fundamentally alters the way companies and institutions will do business. It should focus on identifying and restructuring the building blocks of value in a way that can drive real transformation and broadly advance against deeper challenges and, in doing so, quickly achieve much greater results from the same set of lean tools and practices.

But doing so requires taking a step back and challenging what appear to be common misunderstandings about implementing lean principles.

Seeing Beyond the Waste

One of the most recognizable activities organizations perform as they embark on going lean is creating a value stream map: a graphic that depicts the progression of information and activities involved in either producing or developing a product or service to meet customer demands. Its application in one form or another has grown so broadly that this tool is now widely regarded as being almost synonymous with going lean.

A classic example of the value stream map is the creation of a cola can, described by James Womack and Daniel Jones in Lean Thinking. The authors depict the sequence of all the activities that go into its production—from mining bauxite ore, through its transformation into aluminum sheets as it progresses through a mill, smelter, and a series of rollers; transportation to the can producer, bottler, store, and a number of warehouses along the way; until it finally reaches the customer’s home. Tracing the can’s step-by-step progression from its most basic elements to its final form and destination makes visible the substantial delays, extra effort, and other wastes that fall between actual processing steps. In total, the vast majority of time—more than 99 percent—is spent waiting, with its materials handled more than 30 times, stored and retrieved 14 times, palletized 4 times—with 24 percent of the material never making it to the customer.4

Because the value stream map looks at the creation of value in an entirely different way, it offers a striking view of how disconnected operations can be—and how riddled with waste they are by design. Going Lean describes the reason for this: The traditional emphasis on optimizing factories for turning out huge batches of identical items at a narrow, anticipated rate of demand drives the adoption of supersized equipment to create large economies of scale—and with it a focus on keeping people and equipment operating efficiently, without regard to the tremendous waste that comes with this.

The challenge, however, is determining what to do with this insight. Too often these value stream mapping exercises serve merely as a backdrop for simplified waste reduction exercises, in which teams assembled from the workforce are asked to tag waste, claiming quick “savings” by reducing excesses where they are seen. And these efforts often presume that waste is simply the result of sloppiness and poor oversight, rather than a symptom of the deeper disconnects described in this book.

In reality, recognizing waste is only a starting point—understanding what drives this waste is most critical and requires significantly more digging.

Learning to See Why

When I assess a factory, I generally begin by walking the floor, starting at final assembly and working my way backward. This lets me quickly get a sense of how lean the facility really is, since disruption and waste are most evident at the end of the line, where all of the problems come together. For many businesses, this is where the assessment ends; they quickly act on these findings, draw down waste, and then move on to the next project.

Such an approach, however, does not necessarily lead to the best results. For instance, one facility I visited recounted how its focus on waste reduction led it to slash its inventories by 20 to 30 percent. The results were severe—stock-outs and workarounds soon mounted to a point that nearly crippled its operations. What was the lesson? Although large inventories point to the existence of a problem, addressing only the symptoms is not the answer. The challenge companies face is not so much in understanding that something must be done but determining what must be done and how best to proceed.5

Where, then, should one begin? After identifying the existence of waste, an organization must dig much deeper to isolate the sources of lag that cause this waste to emerge. A great starting point is using a simple, yet powerful, lean technique known as the “5 Whys.” Toyota found that repeatedly asking the question “Why?” creates a very different plane of understanding and ultimately leads companies or institutions to structuring deeper, more meaningful solutions.6

Each response to the question “Why?” develops a deeper understanding of the underlying challenges. The first answer might make the solution seem as easy as tightening up operating procedures and standardizing work steps (which is where actions often seem to culminate). By the end, however, the need for a more complex, entirely different solution might become clear. Rather than focusing on intuitive answers such as shortening travel distances or eliminating steps where waste is most visible, greater scrutiny shows that creating lasting, more meaningful solutions comes from looking farther and deeper—toward upstream challenges, organizational and information disconnects, or other sources of lag that cause disruption to accumulate.

Understanding that a problem exists is only the beginning; next must come probing questions aimed at understanding why the problem exists.

Key Point: The Power of Asking “Why”

When seeking to understand the cause for high production costs at a complex manufacturing facility, consider how asking the question “Why?” five times can lead to a completely different path to improvement than is revealed by the first response:

![]() When walking the production line, suppose that you find widespread indications of waste: extra work steps, out-of-sequence activities, stockpiles of parts, and partially constructed components that have not moved in a long time. Why?

When walking the production line, suppose that you find widespread indications of waste: extra work steps, out-of-sequence activities, stockpiles of parts, and partially constructed components that have not moved in a long time. Why?

![]() There may appear to be a number of contributing reasons, but suppose most boil down to poorly synchronized activities that cause disruption at various stations in the production sequence. Why?

There may appear to be a number of contributing reasons, but suppose most boil down to poorly synchronized activities that cause disruption at various stations in the production sequence. Why?

![]() On the surface, these disruptions can seem to be the fault of unreliable schedules. However, a deeper look might show that many stem from problems with suppliers: late deliveries and high quality-rejection rates for critical parts. Why?

On the surface, these disruptions can seem to be the fault of unreliable schedules. However, a deeper look might show that many stem from problems with suppliers: late deliveries and high quality-rejection rates for critical parts. Why?

![]() Perhaps answering this question reveals that suppliers struggle to deliver these items when needed because they are needed so infrequently, making demand difficult to forecast. Keeping in stock all items that could potentially be needed might be too expensive. And further scrutiny might show that producing them once demand arises takes months or even years (a challenge that is not uncommon in aerospace and defense, as in the case described at the end of this chapter). Why?

Perhaps answering this question reveals that suppliers struggle to deliver these items when needed because they are needed so infrequently, making demand difficult to forecast. Keeping in stock all items that could potentially be needed might be too expensive. And further scrutiny might show that producing them once demand arises takes months or even years (a challenge that is not uncommon in aerospace and defense, as in the case described at the end of this chapter). Why?

![]() The problem could be that they contain expensive raw materials that have very long lead times; these can take months to produce after demand for the part materializes. Why?

The problem could be that they contain expensive raw materials that have very long lead times; these can take months to produce after demand for the part materializes. Why?

![]() Perhaps because its procurement team does not have the capability, training, or insight to structure contracts in a way that addresses supplier challenges that will impact the suppliers’ business.

Perhaps because its procurement team does not have the capability, training, or insight to structure contracts in a way that addresses supplier challenges that will impact the suppliers’ business.

Demanding a Fundamental Shift

Advancing beyond tactical lean initiatives toward greater lean maturity requires asking questions that reach far beneath the surface in order to recognize the real challenges that drive waste accumulation. The answers to these questions can lead to a very different starting point. Rather than beginning by improving discrete processes or value streams, those leading the effort must first understand the broader reasons for the greatest problems they find—disconnects that drive overreaction, workarounds, and inefficiencies each time conditions shift.

Consider the example above. Asking “Why?” five times revealed entirely different challenges than might have been initially perceived. The extra work steps and inventories seen on the shop floor were a result of a deeper issue. Rather than remove them directly (which might have increased disruption), the real answer is to address a supplier base issue, perhaps by creating multidiscipline procurement teams better equipped to structure purchases in a way that can help suppliers deal with the sources of lag that undermine their performance (like Cessna did, as described in Chapter 3).

This illustrates an important challenge for lean activities everywhere. Those leading these efforts must shift focus from simply driving rapid savings to demanding the fundamental shifts that going lean is all about. They must come to expect more than quick gains from first-order waste reduction and become intent on identifying a new structure for building up value without the disconnects that create lag and loss along the way.

But where should one begin? Enhancing one process area at a time (often the recommended path for value stream progression) offers little relief to a factory where managers are dealing with widely ranging issues.7 Targeted problem-solving methods that intuitively point the way for simple products with fairly straightforward value streams give much less insight into how to proceed within businesses whose vast complexity and scope present myriad potential starting points.

Just as with other aspects of a lean solution, the answer comes down to understanding the end-to-end progression of activities—beginning by rethinking how businesses and institutions put together the building blocks for value.

Assessing the Foundation of Value Creation

We have seen throughout this book that going lean begins with seeing the gaps in the way work is currently managed—beginning at the end of the line where problems accumulate, and then working backward to better understand their causes. By mapping the sequence of processing steps for even a cola can, described earlier in this chapter, it becomes clear that creating value can follow a seriously disconnected pathway, filled with delays, wasteful efforts like repeated palleting and warehousing, and substantial material scrap along the way.

But how can one assess these disconnects across a much more expansive business—like so many today that produce complex products across vast operations? Lean practitioners typically fall back on mapping the value stream; unfortunately, using this method means truncating the map to include only a limited portion of the processing steps in order to maintain a workable scope.8 Yet, narrowly defining the stream of activities in this way can seriously limit the assessment; it stands to miss many important interactions that contribute to the lag that causes much of the waste their efforts seek to address.

Thus, while value stream mapping offers an important means for seeing the problem, applying it as an initial step for addressing the complex challenges many firms face presents severe limitations.9 Refined, localized processing sequences can miss broader issues that must first be addressed. Moreover, even the best improvements might represent only a tiny thread of excellence woven through a vast fabric of activities that remains riddled with disruption and loss. Benefits from improving truncated value streams might be swallowed up within such a complex system.

Firms and institutions can avoid this by conducting a broad assessment of the challenges and interactions throughout their business before launching into targeted improvement activities. The dynamic value assessment (described in Appendix A), offers a structured means to accomplish this. It focuses on gaining fundamental insights into how well operations respond to changing conditions—from shifts in customer needs and desires, to changes in business conditions, to the emerging opportunities and threats that many increasingly face. By systematically reviewing their overall effectiveness in responding to these circumstances, it offers the means to structure a comprehensive approach to progressively addressing the underlying issues—the sources of lag that can undermine their business results.

Beginning with this overarching look at the business will likely drive a different starting point than would otherwise be selected. For instance, rather than correcting waste where it is most apparent—at the end of the line, such as in a manufacturer’s assembly operations where problems become most evident—firms can target those areas of greatest lag that cause this waste to accumulate in the first place, and thus create the greatest impact to bottom-line results.

An important outcome of this assessment, therefore, is identifying critical focus areas within a structure for moving forward based on the organization’s current challenges and needs (described in Chapter 5). These transformational focal points can provide needed direction for structuring improvement projects, progressing from mitigating baseline disruption to aligning by product families—a critical enabler for creating dynamic stability. As we will see in Chapter 5, these focal points can serve as a means for structuring improvement initiatives to progressively extend individuals’ insight and involvement—enabling them to take part in addressing major challenges. Their efforts can help in achieving everything from improving baseline stability, to reducing setup times and creating more dynamic supplier arrangements that are important to progressing in lean maturity.

In essence, the dynamic value assessment can serve as a bridge for applying tools and practices that tend to work well for simpler products within stable environments to vast businesses producing complex products or services subjected to dynamic operating conditions—essentially scaling them up so they can be applied in a manner for more consistent, powerful results.

Harnessing Product Families as a Foundation for Lean

Assessing how value is created is a fairly complex undertaking. It requires scrutinizing not just the end product but each of the many elements, or increments of value, that go into building it. For a complex product like a car or an airplane, there might be hundreds or thousands of these elements—each representing distinct increments of value that must be designed, produced, and delivered when needed by a customer. Deciding how these distinct elements will be managed is particularly critical because, in many ways, it sets the foundation for everything that follows.

But where is the best place to begin?

Manufacturers capture these increments of value using a bill of materials (BOM): a classification of all of the materials, parts, and components that go into their products and the parts that go into them. This serves as the basis for everything from how they plan and execute production, to planning capacity, to scheduling operations. In essence, the BOM represents a roadmap to creating value, showing the important contribution of each element within the final product—how each of these items that a company or its suppliers must optimally create align with other elements at any given point in production.

In my study of aerospace manufacturing, early attention to the BOM was a fundamental differentiator between businesses that substantially benefited from their lean efforts and those that did not.10 While most had been able to reduce waste, those that had first established an accurate, detailed understanding of what went into the finished product (despite periodic design changes) demonstrated substantially greater bottom-line benefits.

What does this tell us? Before charging ahead to find opportunities for waste reduction, why not begin by refocusing attention on what it is these serve to produce—the product itself ? After all, it is creating this value that is at the heart of lean; operational steps are simply the means to achieving this end. Reconsidering how production planners originally structured these elements (most likely as stand-alone elements to promote economies of scale under the presumption of stable, predictable demand) and shifting instead to a product family orientation wherever possible can create far more benefit than simply focusing on improving existing processes.

Why make this change? Shifting to manage by product families can create a far-reaching result that could potentially impact hundreds or even thousands of individual value streams that have yet to be mapped, creating solutions that otherwise might never have been possible.

Promoting Variation Leveling

Despite the importance of product families, many lean efforts appear to spend little time evaluating their makeup, instead quickly leaping ahead to the more tangible tasks of mapping the processing steps within their value streams. Product families are often identified as the end items that are delivered to the customer. For instance, a product family for an automobile producer might be a family of cars, a mind-set that misses the opportunity to draw on commonalities across their increments of value. This focus significantly limits their ability to leverage one of product families’ greatest benefits: a structure for promoting variation leveling—dampening out internal disruption that is caused by shifts in the environment.

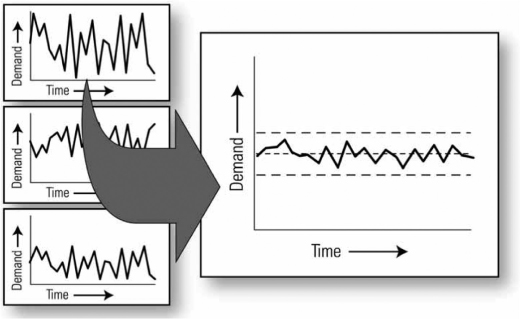

Figure 4-1 illustrates the mechanism for creating this variation leveling effect. The graphs on the left illustrate the variation in customer demands for individual parts needed to support production operations. Managing them individually requires some sort of buffering, either padding production schedules or accumulating inventories, to ensure their timely delivery despite severe uncertainty in demand. Yet these buffers represent sources of lag that respond poorly to changing circumstances. As described in Chapter 2, despite working well within a stable environment, these actions might break down and make matters even worse when conditions suddenly shift.

Figure 4-1. Leveraging Commonalities to Promote Variation Leveling11

We can see the effect of this shift on the right side of Figure 4-1; by managing a group of items sharing common manufacturing characteristics as a single group (as is done in a mixed-model operation commonly seen at Toyota), their combined variation flattens out. Managing these items together as a seamless product family effectively dampens out the externally driven disruption that would impact performance and progress to other workstations upstream.

Making this work requires identifying opportunities for variation leveling—not just with the end item, but throughout the creation of value. For manufacturers, this means grouping together those elements sharing “common materials, tooling, setup procedures, labor skills, cycle time, and especially work flow or [process] routings.”12 They can be produced from beginning to end by teams working together in manufacturing cells staffed with people working as teams to turn out complete end items, components, or clearly severable portions of major operations. The ability to switch seamlessly back and forth from producing one item and then the next makes it possible to dramatically dampen the variation from changing demands of individual items, with significant effects beginning after combining just a handful of items.13

Performing an early assessment to identify opportunities for aligning product families in a way that optimizes the grouping of common elements is critical. It should be conducted before major changes are made, like outsourcing major elements of work, in order to keep from locking out the ability to make important shifts. Doing so will increase understanding product families as a means for promoting value stream thinking, defining them as the driving mechanisms for routing out lag. Moreover, identifying product families that promote this result farther back in the continuum of value creation stands to amplify the benefits, expanding efforts past narrow threads of savings toward creating broad webs of improvement whose benefits extend across the entire value-added map, driving down uncertainty across a wide range of activities.

Case Example: Using Product Families as the Focal Point for Driving Down Lag and Loss

As the Defense Department’s largest logistics combat support agency, the Defense Logistics Agency (DLA) must overcome harsh conditions to provide supplies to meet the dynamic demands of military and civilian customers around the world. One of its challenges is obtaining spare parts for out-of-production weapons systems—aircraft, tanks, and ships, which might contain tens of thousands of parts, any of which can require replacement in order to keep a system operational. Not only are these parts critical, they tend to be very expensive.14

Complicating matters are low and sporadic customer demands for many of these parts, making required inventories and ordering frequencies almost impossible to accurately predict. Moreover, supplier lead time—a key measure of lag—is generally substantial; the time between placing an order and receiving parts often ranges from many months to well over a year. This means planners’ already challenging jobs are complicated by the need to forecast demands that might occur well into the future, creating even greater lag. Often with no active production capability and limited inventory (it is too expensive to stock quantities of millions of unique items without solid evidence of current need), delivering what the customers need just when they need it is truly a daunting task.

One project, called Supplier Utilization Through Responsive Grouped Enterprises (SURGE), pointed to a solution. Rather than managing items individually, it sought to demonstrate the real-world applicability of product family–based groupings—sourcing together a traditionally problematic group of items (hydraulic tubes for fighter jets) as a means for creating long-term supplier relationships for overcoming these constraints. In theory, managing like items (those formed from common materials utilizing similar manufacturing methods) together would help suppliers overcome their individual uncertainties by managing them as a combined group. Their relative production interchangeability should help smooth out the overall demand pattern, creating the variation leveling effect depicted in Figure 4-1, resulting in greater predictability, lower costs, and improved product quality.

Initial results were dramatic.15 A supplier substantially slashed its lead times—as much as two-thirds on some parts—while dramatically increasing its ability to respond to unexpected demand surges. Delivery schedules were generally met, even for selected items that experienced an unexplained demand spike of nearly 1,000 percent. And this greater responsiveness did not cost more, as one might expect. Instead, prices dropped, by as much as 30 percent for individual items across the family.16

Corporations like Cessna Aircraft Company have also attained major benefits by applying a variation of this approach. Rather than launching headfirst into new, long-term contractual arrangements that would relinquish responsibility and authority for producing their parts, components, or major assemblies to their suppliers, Cessna recognized the need to take a step back and begin by gaining a deeper understanding of the elements that go into these products.

Cessna first mapped common materials across its BOMs that could be more effectively managed together as combined groups (it refers to these as Centers of Excellence, or COEs, as described in Chapter 3), commonalities that normally would be lost among disparate supply arrangements. By creating arrangements for manufacturing cells with suppliers to produce these items together to maximize the variation smoothing benefits, it was able to slash lead times and prices and promote dramatically more reliable flow, even for some of the most challenging materials.

But Cessna goes further still, remaining engaged with its suppliers, helping to streamline their value streams. The company begins by training these suppliers in applying lean principles to gain real benefit from managing by product families. To support their efforts, Cessna makes its own flexible, low-cost raw material purchasing arrangements available. And it created a low-quantity, pull-based system to minimize the amount of inventory that must be held by Cessna and these suppliers, slashing inventory costs for each.

As of this writing, the company’s results have been remarkable; some product families slashed lead times from thirteen weeks to only five days, while concurrently slashing costs by 15 to 20 percent.17 Moreover, this new supplier base structure dramatically speeds up sourcing of new items. Since COE suppliers must openly share information about their operations and cost structure, parts can quickly be added into existing families without delays from evaluating capacity, quality, delivery, cost, and performance, factors for which its approach gives specific information and current history. By cutting sourcing time from weeks to days and providing a solid starting point for determining pricing, the company has slashed a key source of lag related to introducing new products.

By first taking a step back and rethinking how individual elements can be better combined before proceeding with process improvements or supplier arrangements, companies and institutions can achieve greater transformation than would otherwise be possible to recognize. Family sourcing can powerfully shift the way business is done, enabling companies to see across far-reaching, diverse operations, organizations, and information systems before restructuring and locking out these potential solutions.