APPENDIX A

A Framework for Conducting the Dynamic Value Assessment

THE DYNAMIC VALUE ASSESSMENT is intended as a data-gathering and evaluation activity to help in implementing lean dynamics by gauging the effectiveness of creating value within the real challenges faced by complex businesses operating within an uncertain and changing environment. It can offer important insights that are critical to identifying the starting point, implementation structure, and measurement focus that will guide a lean dynamics program.

Why is this needed? We have seen throughout this book that the best solution does not necessarily follow the problem. For instance, when we map out the progression of activities involved in creating a cola can (described in Chapter 4), we can see that it follows a tremendously disconnected pathway, filled with delays, wasteful efforts like repeated palleting and warehousing, and substantial material scrap along the way. The intuitive answer is to restructure these processes (following well-documented lean methods) to streamline flow and eliminate waste. Such an approach tends to work well for simpler products and operating environments; the problem, however, is that this approach does not seem to scale up well—it can bring confusion, conflict, and the potential to stumble when applied to vast operations producing complex products or services.

Lean dynamics overcomes this challenge by structuring around a less-intuitive solution. Rather than adopting a generic “continuous improvement” mantra, attempting to directly address waste everywhere it is observed based on the intuitive belief that it will somehow lead to improved customer value, it focuses these efforts around deliberately identified transformational focal points (described in Chapter 6). Focusing on advancing these makes clearer how individual initiatives should be sequenced, their specific objectives, and how to apply classic lean methods for eliminating the lag that causes the waste that degrades their value. This also promotes the understanding that improvements will likely be incremental; that interim solutions will likely be necessary, requiring an iterative approach to advancement—essentially a targeted continuous improvement program—rather than making a direct leap to the final result.

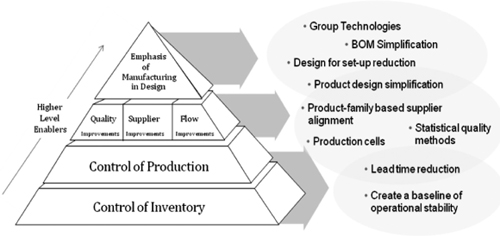

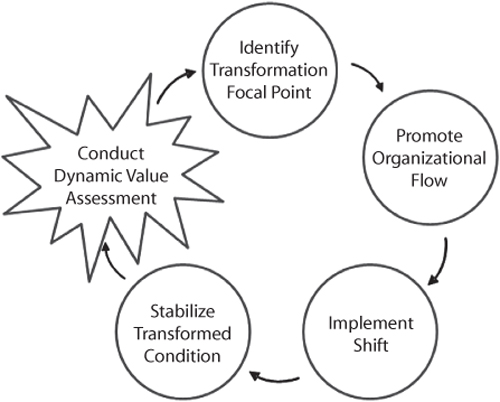

As depicted in Figure 7-1, the dynamic value assessment serves as the foundation for an iterative cycle of advancement that identifies a progression of focal points (based on the firm’s or institution’s capabilities and degree of lean maturity, described in Chapter 6). Initial focal points should aim at attaining a baseline degree of operational stability; subsequent attention can go to fundamentally restructuring how increments of value are produced by combining them into product families at different points along their progression (described in Chapter 4). Each of these should seek to concurrently dampen out all forms of lag—operational, information, decision making (organization), and innovation—while decreasing variation and mitigating its disruptive effects on operations and transformation efforts.

Where, then, should a dynamic value assessment begin? First, it should baseline the organization’s dynamic value creation. Companies and institutions should begin by taking a step back from their day-today activities and taking a fresh look at what they produce today, how well they accomplish this, and how well what they do meets their customers’ needs. This assessment offers a powerful means for moving beyond a conceptual understanding of lean dynamics and learning how it specifically applies to individual businesses or institutions, building a specific understanding of how well the company or institution is positioned to create dynamic value over time (which can be graphically displayed using the value curve, whose construction is described in Appendix B).

Next is determining the organization’s starting point—both the relative capabilities of its operations, and its overall stage of lean maturity. This requires more than measuring actions or even outcomes, each of which can be misleading in isolation. It requires identifying the company’s or institution’s level of stability—where it stands within the hierarchy of lean implementation described in Figure 7-2, a key to determining which focal points it is ready to pursue. It also should include an assessment of its general state of lean maturity (described in Chapter 7); this can help point to the general mind-set that exists—a key foundation for creating the vision, case for change, and plan of action that can set the course to advancing to sustainable lean (the ultimate state of maturity represented by a flat value curve). This is perhaps the most critical step; what is most important is the organization’s potential to continue to advance despite the pressures to stagnate and simply refine gains within a given level of maturity.

Finally, the information and analysis gained from a dynamic value assessment offer powerful insights to help in structuring the transformation, optimizing starting points for the greatest benefit and promoting a seamless progression through the levels to lean excellence.

The following sections describe each of these three elements: baselining dynamic value creation, determining the starting point, and structuring the transformation.

Baselining Dynamic Value Creation

Value is tangible and quantifiable. It can be measured against what customers are willing to pay for what a company or an institution produces, compared to what it costs to accomplish this. Each of these is strongly affected by the dynamics of its operating environment (which is displayed by the value curve, described in Appendix B) and the degree to which the organization is equipped to respond (which relates to its lean dynamics maturity).

Assessing the dynamics of value begins with determining the extent to which a business or an institution understands and actively considers the impact of the dynamic conditions outside of the business—the shifts in customer needs and desires, as well as overall business conditions. This understanding serves as the foundation for determining how well a company will perform when it faces the threats to the emerging opportunities that its dynamic operating environment creates.

Key outcomes will include an understanding of major wastes and lag in current operations, challenges in meeting specific customers’ needs, and transformational focal points whose advancement can broadly affect these results.

Assessing the Product

Before charging ahead to scrutinize processing steps for waste reduction, businesses and institutions should take a step back and remind themselves of what value they create and reassess the way they have chosen to assemble this value. Asking product-oriented questions is particularly valuable in that it identifies a path to improvement that is far more actionable, such as:

Does the organization have a deliberate rationale for the way it creates value? For manufacturing companies, for instance, reconsidering how production planners originally structured these elements (most likely to support a presumption of steady-state operations) and then restructuring based on a lean dynamics philosophy stands to create far more benefit than will simply focusing on improving existing processes. Deciding how these distinct elements will be produced—whether they will be supplied as separate entities or combined as part of broader product families—sets the foundation for everything that follows (as described in Chapter 4).

Is there an accurate way of displaying the severable increments of value, their relative importance, and those giving the most trouble? Identifying these increments of value is an important starting point, one that should precede detailed activities aimed at realigning value streams or restructuring business processes. But many businesses and institutions launch right into efforts aimed at eliminating waste where it is most evident, either skipping or minimizing this important step, potentially cutting themselves off from deeper transformation and from the more specific, tangible, actionable focus to which this can lead. For instance, doing so early can create the opportunity for managing these elements together as product families (described in Chapter 4), thereby mitigating lag in operations, information, decision making, and innovation

Understanding the Customer

A critical step in conducting a dynamic value assessment is performing an assessment of the customer. Many methods for gathering information are available, ranging from surveys, to brainstorming sessions, to focus groups. The intention of this book is not to present these in depth, but to briefly describe the types of information that might help characterize the challenge.

Who is the customer? It is surprising how difficult it can be to answer what seems such a straightforward question. On the surface, those asked might see the answer as common sense; they might simply name the business entity to which they ship, or the purchasing representative with whom their transaction is coordinated. But, on deeper questioning (akin to the 5 Whys), this initial answer might quickly break down as follows:

![]() How should the customer be defined? This might not be intuitively evident, since parts of the business might relate to different parts of the customer’s organization—particularly for large organizations.

How should the customer be defined? This might not be intuitively evident, since parts of the business might relate to different parts of the customer’s organization—particularly for large organizations.

![]() Who is giving you customer feedback? If an individual is then identified, does he or she have sufficient span of insight to understand how well your products and services meet their genuine needs?

Who is giving you customer feedback? If an individual is then identified, does he or she have sufficient span of insight to understand how well your products and services meet their genuine needs?

![]() Who are your customers’ customers? Who actually uses your products and services? Is it a worker on a production line or a consumer at home?

Who are your customers’ customers? Who actually uses your products and services? Is it a worker on a production line or a consumer at home?

Identifying precisely who the real customer is can be difficult, but it is a crucial step to assessing how well the business or institution is meeting customers’ expectations, which is what creating value is all about.

What do these customers value? Customers’ needs and desires will continue to change; a lean dynamics effort seeks to anticipate and respond to these changes with efficiency and innovation.

![]() What are their stated and unstated needs and preferences?

What are their stated and unstated needs and preferences?

![]() What challenges are customers currently facing? Are business customers facing different issues than the end customer?

What challenges are customers currently facing? Are business customers facing different issues than the end customer?

![]() Do customers seem interested in collaborating to create solutions that meet their specific needs?

Do customers seem interested in collaborating to create solutions that meet their specific needs?

Such insights are helpful to identifying and prioritizing transformational focal points, which can help optimize the benefits that lean dynamics efforts achieve up front for the corporation or institution and its customers.

Do your offerings coincide with what customers value? Very often, organizations have little insight into how well they are satisfying the needs of their customers. At a top level, the result is clear. Poor performance leads to lost sales, which translates to lower revenue. Customer satisfaction surveys can glean a little more information. However, these act as lagging indicators and rarely seem to isolate the actual factors that customers value. Asking a few simple questions to specific customers might help.

![]() How well has the business or institution performed in meeting customers’ needs? Can product characteristics, quality, turnaround speed, on-time delivery, and other basic attributes be broken down to show performance for specific customers?

How well has the business or institution performed in meeting customers’ needs? Can product characteristics, quality, turnaround speed, on-time delivery, and other basic attributes be broken down to show performance for specific customers?

![]() What indications exist of the customer’s trust and loyalty (this is substantially different from a measure of customer satisfaction)? What operational limitations might be contributing to these results?

What indications exist of the customer’s trust and loyalty (this is substantially different from a measure of customer satisfaction)? What operational limitations might be contributing to these results?

![]() Has the organization focused on mitigating the customers’ challenges?

Has the organization focused on mitigating the customers’ challenges?

![]() Have customer relationships advanced as a result of performance?

Have customer relationships advanced as a result of performance?

![]() How do these answers relate to internal assessments of the business’s strengths, constraints, and lag? Are customer issues seen as separate from internal performance issues or are correlations and root causes identified?

How do these answers relate to internal assessments of the business’s strengths, constraints, and lag? Are customer issues seen as separate from internal performance issues or are correlations and root causes identified?

Integrating customers’ perceptions of business performance is important to gaining customer trust, which can create opportunities for expanding existing business and sets the stage for moving to a collaborative relationship (whose benefits are described in Chapter 9). Moreover, these insights can serve as a powerful starting point for identifying areas that might serve as focal points for transformation (as depicted in Figure A-1).

Quantifying the Dynamics of the Environment

Taking a hard look outside the business at the realities of the environment is a key part of understanding the customer. As described in Chapter 2, this is critical for breaking from the “presumption of stability” that holds so many businesses hostage.

Doing so takes asking hard questions about the range of challenges the business or institution is likely to face.

![]() How likely is it that catastrophe will strike again (e.g., Katrina, September 11), and what might the impact on the business be?

How likely is it that catastrophe will strike again (e.g., Katrina, September 11), and what might the impact on the business be?

![]() How might external forces drive different customer demands (e.g., spiking fuel prices affecting car-buying patterns)?

How might external forces drive different customer demands (e.g., spiking fuel prices affecting car-buying patterns)?

![]() What disruptions might interrupt the flow of resources on which you depend, such as energy, raw materials, or credit?

What disruptions might interrupt the flow of resources on which you depend, such as energy, raw materials, or credit?

![]() Will government regulation cause you to shift your business approach (e.g., health care, environmental issues)?

Will government regulation cause you to shift your business approach (e.g., health care, environmental issues)?

![]() Will competitors create new, game-changing products that shift the direction of the industry?

Will competitors create new, game-changing products that shift the direction of the industry?

Evaluating such questions might include conducting scenario-planning exercises to help those participating in the transformation understand that conditions are inherently not stable and that any solution must address this inevitability. This can reinforce the need to mitigate lag that can amplify the effects of a disruption, building the need for flexibility and responsiveness into the core of business strategies.

However, despite the best preparation, it is unlikely that anyone would have envisioned such disastrous situations as September 11 or the financial meltdown of 2008. Therefore, what is most powerful about this assessment might not be the specific actions that it drives; instead, the assessment leads to the general understanding that business must be structured in a way to respond when the unthinkable happens. This includes mitigating lag to reduce the amplification of external sources of disruption within the business, creating variation-leveling mechanisms (described in Chapter 4), and taking other strategic actions that can sustain demand even in times of crisis (described in Chapter 9).

Analyzing the Data

Next, firms and institutions need to build a comprehensive understanding of how these real and potential external forces stand to impact their business. This is a critical, but often neglected foundation for lean transformation. Calculating value margins and relating them to product changes and to internal activities offers the ability to create a baseline understanding of the firm’s capability to turn out stable value across a range of conditions (its construction is described in Appendix B).

A steep value curve shows that a problem exists. However, this is only the starting point. What is important is digging deeper with probing questions aimed at understanding why (using the 5 Whys approach described in Chapter 4). Some of the lines of questioning are identified in Appendix B.

Determining the Starting Point

The dynamic value assessment serves as an important foundation for structuring a transformation to a lean dynamics way of doing business, both at the outset and, in a dynamic fashion, throughout its implementation. The information it captures is important to developing a vision, strategy, and plan of action that will lead the way to real transformation. But this takes finding a way to focus the effort and maximize the early, tangible benefits needed to sustain enthusiasm, within a deliberate structure that promotes long-term advancement.

Categorizing Findings

Categorizing these findings can help highlight a core distinction of lean dynamics—that progressing with improvement does not mean beginning at the end and working backward; it recognizes that problems or challenges are often rooted in other parts of the organization, and seeks to understand these and address them. This is key to identifying where an organization stands so that it can properly address its challenges from a holistic standpoint for optimal results.

Although information will probably need to be gathered by functional area (using a process marked by substantial iteration in order to understand the progression of challenges that cross traditional functional boundaries), a way of pulling together this information is needed to spot trends and support major findings. Categorizing findings by each of the four forms of flow (operational, organizational, information, and innovation—described in Chapter 1) can help pull together qualitative and quantitative findings to form conclusions regarding key areas ranging from capabilities to major challenges within activities, between activities, or across the organization.

Identifying Transformational Focal Points

One of the greatest challenges to implementing lean improvements within a complex business or institution is identifying a starting point for taking action. Chapter 6 describes how aerospace manufacturers stood out in how they knowingly or not implemented their lean practices in a manner that progressively addressed a core transformational focus—creating a baseline for stability before advancing to more recognizable lean practices. This same framework seems broadly applicable; by successively addressing the greatest drivers for mitigating uncertainty and disruption, a core challenge facing many businesses, organizations of all types can advance in a structured manner to first attain a baseline of stability, and then advance further to more progressive focal points. Figure A-1 depicts examples of potential focal points based on this hierarchy (a sampling based on research in the aerospace industry) for implementing long-term lean dynamics solutions (described in Chapter 6).

Figure A-1. Examples of Focal Points for Transformation1

Managing the Shift

The results of the dynamic value assessment can help identify key focus areas within a logical structure that simplifies the complexity and scope of the transformation while creating dramatic improvements to customer value and promoting substantial shifts toward a coordinated objective.

A structured approach to lean dynamics will likely need to be iterative in nature, as described in Chapter 7. The dynamic value assessment should be an integral part of this progression, as depicted in Figure A-2. After identifying a starting point, restructuring to create the necessary operational flow (as described in Chapter 5), organizations can implement the shift, and stabilize and measure results. Since carefully selected focal points will likely produce widespread changes crossing different parts of the organization, it is important to conduct a fresh dynamic value assessment to understand the full impact, and to determine whether adjustments should be made to existing efforts, or whether new objectives should be pursued.

Figure A-2. Identifying Focal Points for Transformation

Identifying the State of Lean Maturity

Chapter 7 describes how organizations tend to advance toward lean maturity and the general characteristics that apply to businesses and institutions at each stage of this journey. Why is this important? Because these characteristics can serve as a guide as organizations gauge their current state of maturity and lean dynamics capabilities, as well as point to where they should focus their efforts.

It is important to recognize that gauging maturity is not about simply quantifying progress in implementing operational lean tools and techniques; we have seen that this narrow focus can distract from deeper objectives, causing stagnation at plateaus along the way. What is most important is advancing toward robust value creation, as represented by a flatter value curve. Therefore, the key focus is on progressing against the four underlying supporting characteristics described throughout this book: insight, inclusion, action, and integration. Chapter 7 offers a number of indications that the assessment should examine, in order to develop a sense of progress in advancing from tactical lean to advanced maturity.

It is important to differentiate between assessing lean dynamics maturity and the capabilities that commonly apply to these levels. Organizations at various levels of maturity might apply any range of initiatives. An organization that has reached a strategic lean level of maturity, for instance, still might apply targeted, tactic-oriented tools, like addressing suppliers’ long lead times by isolating and addressing bottlenecks using investments in equipment and raw materials to meet rapidly changing production needs.

What distinguishes a company’s or an institution’s level of maturity is not so much the specific tools or activities it applies but the focus of these actions toward advancing to sustainable lean—a key to progressing through the natural plateaus that can halt progress along the way.