Tourism research

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

appreciate the critical role of research within the field of tourism management

describe the main types of research that are relevant to the field of tourism studies and outline the circumstances under which each is most suitable

differentiate between induction and deduction, and describe how these two approaches are complementary

classify any specific research initiative as per its adherence to the main types of research

list the major types of techniques associated with primary and secondary research

understand the advantages of mixing quantitative and qualitative research approaches in the same projects

discuss the basic stages of the research process

describe the four main levels of investigation and explain how they complement each other within a comprehensive research project.

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

The previous chapters of this book demonstrate that tourism is an increasingly diverse and complex phenomenon that requires sophisticated management and planning if it is to be practised in a sustainable as well as competitive manner by destinations and businesses. Whether the primary motivation is to maximise the positive impacts and minimise the negative impacts of tourism (as with most destinations), or to maximise profits (as with most businesses), stakeholder objectives can only be achieved if decisions are informed by sound knowledge. This is obtained through the pursuit of properly conceived and executed research, or the systematic quest for knowledge. It is therefore critical for students of tourism management to be familiar with the research process and related issues. The purpose of this chapter is to provide an introduction to research as it relates to tourism studies. The following section examines the various types of research and illustrates their applicability to tourism. The broader research process, including problem recognition and formulation, identification of appropriate methodologies or methods, data collection, data analysis and interpretation, and data presentation, is described in the final section.

TYPES OF RESEARCH

TYPES OF RESEARCH

There are several standard ways of classifying research in the field of tourism studies and elsewhere, and four of the most important are discussed as follows:

basic versus applied

cross-sectional versus longitudinal

qualitative versus quantitative

primary versus secondary.

Allowing for a certain amount of overlap within each pairing (e.g. a particular research design may combine elements of the qualitative and quantitative approach), any research initiative can be described simultaneously in terms of all four approaches. For example, a long-term research project examining changing consumer preferences may concurrently be applied, longitudinal, quantitative and primary. Each of these research types in turn is associated with a particular research methodology, or set of assumptions, procedures and methods that is used to carry out the research process. Methodological issues, because they are pervasive, are raised in the following section as well as in the discussion of the research process in the final section.

Basic research

The distinction between basic research (sometimes referred to as pure research) and applied research focuses on the intended end result of the investigation. Basic research reveals knowledge that will increase the understanding of tourism-related phenomena per se, and is not intended to address specific short-term problems or to achieve specific short-term outcomes (Jennings 2010). However, the knowledge gained from basic research may prove relevant in the subsequent context of more specific issues, especially if the knowledge is expressed in the form of general laws, theories or models that have practical ramifications. This is illustrated by the Butler sequence, which is an outcome of basic research that has proven to be highly relevant to the tourism industry (see chapter 10).

Basic research is commonly associated with universities, given their core mandate to engage in the unfettered search for knowledge. Corporations, and smaller ones in particular, are less inclined to carry out this type of investigation, since the ensuing 357applications are not usually apparent right away, and therefore cannot be easily justified on financial grounds. Jones and Phillips (2003) go as far as describing the research cultures of universities and corporations as fundamentally different, with the former focused on publication in academic journals. One intriguing type of basic research is the ‘fishing expedition’. This occurs when the researcher applies many different techniques and experiments to some database or subject matter without knowing what will result, but in the hope that some major and unexpected ‘big catch’ revelation will emerge.

Induction and deduction

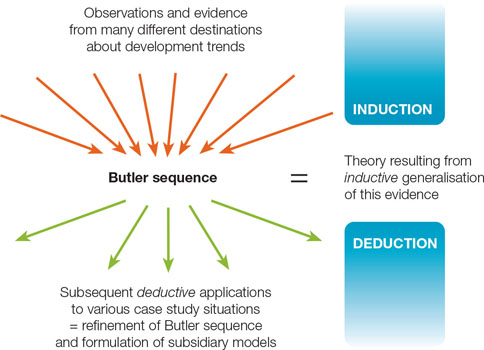

Basic research can be carried out through methodologies of induction or deduction. In induction, the repeated observation and analysis of data lead to the formulation of theories or models that link these observations in a meaningful way. Deduction, in contrast, begins with an existing theory or model, and applies this to a particular situation to see whether it is valid in that case. In other words, induction progresses from the specific (i.e. the evidence) to the general (i.e. the theory), while deduction moves from the general to the specific (Sarantakos 2004). Theories are commonly generated through induction and then applied and assessed through deduction.

Figure 12.1 illustrates this relationship with respect to the Butler sequence, wherein many different observations and unconnected studies led to the formulation of the resort cycle concept through a process of inductive generalisation. These observations pointed towards a common process of accelerated growth culminating in the breaching of a destination’s carrying capacities (see chapter 10). Subsequently, many other researchers have applied Butler’s general model in a deductive way to specific destinations, leading to varying conclusions about its applicability as well as refinements and extensions that take into account these new investigations. These notions of refinement and extension are very important to basic research, since they imply an evolution in our knowledge of tourism-related phenomena.

Often, the testing of a model through the inductive or deductive approach is informed by the formulation of one or more hypotheses, which are informed tentative statements or conjecture about the nature of certain relationships that can be subsequently proved or disproved through systematic testing and other investigation. For example, a researcher testing the Butler sequence (i.e. a deductive approach) may establish the following hypothesis to address one particular aspect of the model:

‘The control of the tourism sector passes from the local community to external interests as the level of tourism development increases.’

Such a statement then provides a focal point for research into the applicability of the model, containing several variables (i.e. ‘control’, ‘local community’, ‘external interests’, ‘increased level of tourism development’) that can be measured, collected and evaluated collectively. As long as investigations continue to verify the hypothesis, then there is no need to alter the model. However, if the hypothesis is rejected, then the model itself needs to be reconsidered. In some cases, the rejection may be a ‘one-off’ occurrence resulting from unusual local circumstances. However, as with paradigm shifts, a pattern of repeated rejection means that a fundamental modification of the original model may be required.

Applied research

As implied in the term, the orientation in applied research is towards specific practical problems and outcomes. These may be associated with product development, the identification of target market segments, community reactions towards specific tourism planning scenarios, or the relationship between tourism and climate change. Applied research is commonly associated with private corporations or government agencies charged with the task of addressing specific issues within certain time and resource constraints (see the case study at the end of this chapter). If industry-based, the research results may be kept confidential so that competitors cannot use this same information for their own purposes. However, like basic research, applied research can also lead to theoretical breakthroughs and the advancement of knowledge if the results are made available to the public. The psychographic typology is one example (see chapter 6).

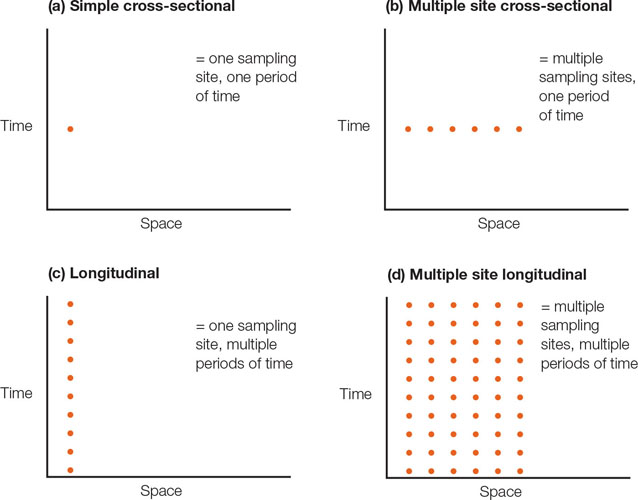

Cross-sectional research

The difference between cross-sectional research (sometimes referred to as latitudinal research) and longitudinal research is based on the time period that is represented by the resulting data. Cross-sectional research entails a ‘snapshot’ approach that describes a situation essentially at one point in time (although the data may be collected over several weeks or months). In its simplest form, cross-sectional research is undertaken at a single site (scenario (a) of figure 12.2). A more complex variation involves the collection of information at multiple sites as per scenario (b). Scenario (a) might involve the administration of a one-time survey during the Gold Coast Schoolies Week in 2014 to determine the attitude of residents toward this event (see figure 12.3). Scenario (b) might involve a similar one-off Schoolies Week survey carried out simultaneously in Hervey Bay, the Gold Coast and Sunshine Coast. The advantage of the second scenario is the opportunity to make comparisons and perhaps identify common trends, but it has the disadvantage of being more expensive. In addition, careful planning must be exercised in order to ensure that all the surveys are carried out at about the same time and in a similar manner.

359FIGURE 12.2 Basic cross-sectional and longitudinal surveying options

Longitudinal research

FIGURE 12.3 Schoolies Week on the Gold Coast — a tourism event in need of more research

Longitudinal research

Longitudinal research examines changes in the target phenomenon over a period of time. Forward longitudinal research commences at some present or future time and continues for a usually defined period into the future. Backward longitudinal research involves the reconstruction of the phenomenon during some stipulated period in the past. In both scenarios, which can be combined, a sequence of snapshots is produced and analysed. An example of scenario (c) of figure 12.2 (i.e. single-site forward longitudinal research) is the monitoring of Gold Coast resident attitudes toward Schoolies Week over the five-year period from 2014 to 2018. The most comprehensive (and most expensive) form of forward longitudinal research entails the examination of many sites over multiple time periods (scenario (d) of figure 12.2). This scenario would occur if the five-year period applied to the Gold Coast, Sunshine Coast and Hervey Bay. The International and National Visitor Surveys, conducted by Tourism Research Australia, are good illustrations of this latter approach. As a result of such ambitious investigations, considerable insight is gained into spatial as well as temporal patterns, and on this basis we are more likely to generate useful models and theories. Continuing problems, however, include the possible necessity of extending the time period of the inquiry if no clear trends emerge within a given timeframe, and logistical challenges in doing so.

A variation in forward longitudinal research carried out by survey is the continued solicitation of the same respondents from one time period to the next. The advantage of this approach is the ability to monitor the changing behaviour of known individuals. However, such an approach may not be practical due to the attrition of participants due to death, migration or respondent fatigue. This is a more realistic option where the time period of the research is more limited. For example, consumers who have already booked a trip to a particular location may be asked to express their expectations about that destination. Upon their return several weeks later, they could be asked whether their expectations were met. Note that this form of forward longitudinal research is also distinguished by the different questions that are asked in each phase of the surveying.

A major challenge for longitudinal research is maintaining consistency in the research design over the duration. If, for instance, the survey questions, definition of ‘resident’ or sample size is radically altered halfway through the period of investigation (whether the approach is forward or backward), or a change is made in the cities where residents are surveyed, the subsequent results will no longer be neatly comparable to data collected prior to the changes. Any apparent trends that emerge from the study will therefore be misleading. In general, longitudinal research, and forward longitudinal research in particular, is infrequently undertaken in tourism studies due to the many methodological challenges it entails (Ritchie 2005), as well as the practical need for academics to publish research in a timely manner in order to best progress their career development.

Qualitative research

The distinction between qualitative research and quantitative research is concerned mainly with the type of data that is sought. Qualitative research can be ‘negatively’ defined as a mode of research that does not place its emphasis on statistics or statistical analysis; that is, on the objective measurement and analysis of the data collected (Goodson & Phillimore 2004). In terms of subject matter, it usually involves a small number of respondents or observations, but considers these in depth (see Breakthrough tourism: Interrogating yourself with autoethnography). It is for this reason that qualitative research methods are sometimes referred to as ‘data enhancers’ that allow crucial elements of a problem or phenomenon to be seen more clearly and in greater depth. Qualitative research is suited for situations where little is known about the subject matter, since the associated methodology is intended to gain insight into the phenomenon in question. Socially or psychologically complex research issues are also amenable to qualitative analysis, which is well suited to capture or clarify nuances of meaning and associated external factors.

breakthrough tourism

![]() INTERROGATING YOURSELF WITH AUTOETHNOGRAPHY

INTERROGATING YOURSELF WITH AUTOETHNOGRAPHY

Calls for tourism research to make more use of personal narratives have led some researchers to include their own subjective experiences and perceptions in their investigations. Autoethnography is a potentially useful tool for interrogating changing ideas about the self within a broader social perspective. It was employed by Coghlan and Filo (2012) to compare their respective experiences as participating cyclists in philanthropic adventure tourism and charity sport events. The tourism event, during which Coghlan collected autoethnographic field notes, was the 361Hospital Foundation’s Cardiac Challenge, a three-day cycling trip between Cairns and Cooktown in northern Queensland. The sporting event, which involved participant focus group data collected by Filo, was the Lance Armstrong Foundation Livestrong Challenge in the United States. The interdisciplinary exploration of deeply personal aspects of these experiences revealed a greater understanding of common meanings, including a strong sense of connectedness with the target cause and with other participants. A prevalent sense of wellbeing was also evident. The links between these two types of activity were therefore much stronger than expected, opening the way for further and richer interdisciplinary collaboration between sport and tourism researchers. The discomfort felt by many researchers in positioning themselves as research subjects helps to explain why autoethnography has not yet been more widely adopted as a mode of qualitative research. That the results are not meant to be generalisable to broader populations is also a cause for hesitation by conventional researchers. For the authors, the process was revealed to be very intensive and time consuming, requiring both of them to question the foundations of their respective fields of study. For the managers of philanthropic and charity events, autoethnography yields valuable insights into participant motivations and outcomes. ‘Wellbeing’, for example, seems to have promise as the basis of a more holistic marketing strategy to attract new participants and support, pending further investigation.

An example of qualitative research would be a situation where the researcher non-randomly selects a group of ten Gold Coast residents and conducts an in-depth two-hour interview with each to see what they think about Schoolies Week. Many researchers criticise such ‘data-enhancing’ qualitative research for lacking the objective rigour and validity of a statistical approach, and for not necessarily being representative of any group larger than that which was actually interviewed or observed. This criticism, however, is best directed towards the careless execution of qualitative methods, and not to qualitative methodology itself, which can be extremely rigorous and challenging in its assumptions and applications. Text analysis software such as NVivo and Leximancer are increasingly popular tools for applying methodological rigour to qualitative data. Another way of improving the validity of such research is to expose the research subject matter to a variety of qualitative methods (see Contemporary issue: Qualitative reinforcement).

contemporary issue

![]() QUALITATIVE REINFORCEMENT

QUALITATIVE REINFORCEMENT

To reveal the experiences of migrant Polish tourism workers in the United Kingdom, Janta and colleagues (Janta et al. 2011) used a variety of qualitative research methods. In the first stage, a netnographic method was used to analyse social media postings from these workers, which had the advantage of capturing the perspective of current as well as former workers, since the ‘footprint’ of past employees was retained on some websites. In addition, traffic on UK-based Polish websites increased ninefold during the two-year study period, thereby providing a critical 362mass of material and revealing its importance as a mode of communication for these workers. In the second stage of the study, based on these netnographic outcomes, an in-depth interview method was used with six migrants to clarify indicative themes that would inform an online survey. These semi-structured interviews evolved around the four themes of (1) reasons for entering the sector, (2) career paths, (3) adaptations, and (4) experiences within the sector. Unlike the first-stage netnography, the researchers could be regarded as ‘co-creators’ of knowledge here because of the close and prolonged interpersonal nature of the interviews. In the study’s third stage, an online survey (requiring a moderate level of researcher involvement) was posted to United Kingdom-based Polish social networking sites and internet forums. This yielded 315 usable completed questionnaires out of 420 received. This survey method included two open-ended questions to determine what respondents felt they gave to and received from the sector. Because of the non-systematic way in which the participants were recruited, none of the three methods of analysis could be said to provide a representative sample of the target population. However, comparison of the three databases compiled through these methods resulted in cross-validation since they all revealed common macro-themes of ‘relationships’ with British people, other Poles, and other foreigners. The results were confidently presented by the authors as ‘emergent themes’ that could usefully inform subsequent research on this tourism stakeholder group.

Quantitative research

Quantitative research relies on the collection of data that are then analysed through a variety of statistical techniques. Numerous quantitative research methods are used in the field of tourism studies, and it is beyond the scope of this introductory tourism management text to describe these methods. It can be said, however, that qualitative techniques are ‘data enhancers’, whereas quantitative research techniques typically are ‘data condensers’ that yield a relatively small amount of information about a large number of respondents or observations. Table 12.1 depicts some of the contrasting characteristics associated with quantitative and qualitative research techniques and in so doing illustrates the very different assumptions and philosophies that inform each approach.

TABLE 12.1 Quantitative and qualitative research styles

Source: Neuman (2010)

| Quantitative style | Qualitative style |

| Measure objective facts | Construct social reality, cultural meaning |

| Focus on variables | Focus on interactive processes, events |

| Reliability is the key | Authenticity is the key |

| Value free | Values are present and explicit |

| Independent of context | Situationally constrained |

| Many cases or subjects | Few cases or subjects |

| Statistical analysis | Thematic analysis |

| Researcher is detached from subject | Researcher is involved in subject |

Because it often involves a rigorous process or ‘road map’ of hypothesis formulation, detached observation, data collection, data analysis and acceptance or rejection of the initial hypotheses, quantitative research is regarded as the core of the scientific method. This paradigm has always been at the heart of the natural sciences, but has only recently become more prevalent in tourism studies. It claims to ‘reliably’ reflect the ‘real world’ through its rigorous procedures and the ability to extrapolate its results to a wider population if executed properly. Many of its exponents, accordingly and unfairly, adopt a dismissive attitude towards ‘soft’ and subjective qualitative research approaches.

This perception is unfortunate, since the two research approaches are complementary. For example, much inductive research is qualitative and intuitive, but can generate models and hypotheses that may be tested using quantitative (or qualitative) techniques. Similarly, we may accept or reject a hypothesis based on some test of statistical significance, but find that we subsequently have to conduct in-depth qualitative interviews or focus groups to interpret or account for these outcomes. Another link is the possibility of analysing qualitative data, such as newspaper letters to the editor, using quantitative methods such as NVivo-mediated content analysis.

The student, therefore, should be aware of the circumstances under which a qualitative or quantitative approach is warranted, but should further realise that a particular research agenda can usually combine both. This potential for synergy is illustrated by questionnaires that provide for quantitative response patterns (e.g. ‘How old are you?’ or ‘On a scale of 1 to 5, how would you rate Uluru as a tourist attraction?’) as well as qualitative insights through open-ended questions (e.g. ‘Why did you rate Uluru in this way?’) and follow-up focus groups and one-on-one interviews.

Primary research

The distinction between primary research and secondary research depends on the source of the data used by the researcher. In primary research, the data are collected directly by the researcher, and did not exist prior to their collection. This is necessary when the data required to address some issue or problem of concern — for example, Gold Coast resident attitudes toward Schoolies Week — are absent. Hence, a major advantage of primary research is the ability of the investigator to design a tailored research framework relevant to the specific topic and questions of interest. As with longitudinal and multiple site cross-sectional data, a widespread problem is high cost in time and money. There are numerous techniques associated with primary research methodology, some of the most important of which are now described.

Surveys

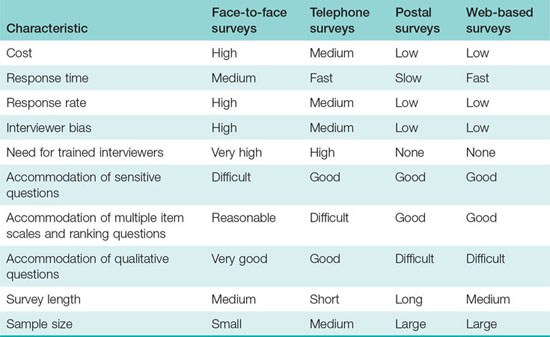

The survey is the most common method for conducting primary research in tourism studies, as in the social sciences more generally. Accordingly, much useful generic information is available for students wishing to undertake this type of investigation (e.g. Fowler 2009). The design and administration of any specific survey (and whether a survey is even the right way to proceed), however, ultimately depends on the goals of the researcher and the resources that are available to conduct the survey. Depending on the responses to those concerns, the researcher can select from three basic types of surveys:

face-to-face interviewing (conducted at households, in the field, or at some other agreed-upon location)

telephone interviewing

distributed (self-completed) surveys (with field, postal, fax, iPad/mobile phone, internet and email variations).

Table 12.2 provides an overview of the key characteristics associated with major surveying techniques. If the researcher has a limited budget and no access to trained interviewers, then a distributed survey is usually the best way to proceed, even though — as with landline telephone surveys — there is evidence that response rates to postal surveys have declined substantially since the early 1970s (Fowler 2009). Web-based options, accordingly, are becoming increasingly popular in countries where most consumers have access to a personal computer or other enabling devices (see Technology and tourism: SurveyMonkey). Face-to-face procedures are warranted where the researcher is interested mainly in in-depth, qualitative responses with a small number of respondents.

Focus groups

Focus groups involve face-to-face group discussions conducted with a small number of people usually pre-selected because of their relevance to a particular research problem (Bloor 2001, Krueger & Casey 2009). A researcher who is interested in resident attitudes toward Schoolies Week, for example, may gather together ten community leaders who are judged to be informed, concerned, willing to participate, and representative of a broader cross-section of the local community. Focus groups rely a great deal on the interactions and synergies that take place among the participants, and are an excellent means of obtaining in-depth, qualitative data (Weeden 2005). They are often used in the initial phases of research to identify problems and issues, and as a prelude to quantitative inquiry.

TABLE 12.2 Characteristics of survey types

Relevant questions that must be asked when considering focus groups as a research method include how large a group to form (optimum group size may be affected by cultural and political factors), who to include, whether to offer some kind of incentive to participants, and how to ensure equitable participation from all members. A more recent possibility is the use of virtual focus groups mediated by online technology such as the voice over internet protocol (VoIP) application, Skype.365

technology and tourism

![]() SURVEYMONKEY

SURVEYMONKEY

The many technical and logistical problems once associated with web-based surveys are being addressed by specialised online services. Major companies, such as SurveyMonkey (www.surveymonkey.com), are focused on building larger customer bases — presenting tourism researchers with an increasingly attractive means of collecting primary social data. SurveyMonkey’s questionnaire design stage allows researchers to create their own questions using specific formats such as multiple choice or Likert-type (1-to-5) scales, or select from a database of questions/statements ‘certified’ as being methodologically sound. A custom branding feature allows the designer to add their own company logo and other desired images to any of many possible templates. For the response collection stage, a single URL is generated that can be included as a hyperlink for distribution via social media networks, websites or email. On a fee-per-response basis, the company can also send a survey on behalf of the researcher to a desired target market segment within the company’s database of respondents. SurveyMonkey’s database comprises over 30 million people in the United States, United Kingdom, Australia and elsewhere, who have been recruited from those who have filled out SurveyMonkey surveys in the past and are willing to fill out other surveys sent to them if they meet the target demographic criteria. Survey respondents are rewarded with charitable donations in their name, sweepstakes entries or other incentives. This option saves the researcher the problem of obtaining their own valid set of responses. Finally, in the data analysis stage, options such as bar charts and pie graphs are available for reporting simple frequencies, distributions and cross-tabulations. SurveyMonkey has also become popular because its basic package is free, although this restricts questionnaires to just 10 questions and 100 responses per survey. Profits are realised because many users will pay progressively higher fees for a sequence of increasingly sophisticated service packages which, for example, allow databases to be readily linked to SPSS software to facilitate more sophisticated types of analysis.

The Delphi technique

The Delphi technique involves assembling a panel of experts, ranging in size from ten or less to as many as one thousand (but typically around 50), who are asked to respond to several rounds (usually three or four) of questioning about a particular research issue (Garrod & Fyall 2005). In each subsequent round, the participants (who remain anonymous) are made aware of the results of the previous round of questioning, so that the opinions expressed in that new round are influenced by those earlier outcomes. Knowledge and opinion are thus systemically focused as feedback to arrive at an eventual consensus about the issue. The Delphi technique is often applied as a forecasting tool to obtain a general picture of the probable future, rather than as a means of achieving highly accurate predictions (which are almost always impossible to attain). Its fundamental principle is that useful speculations will emerge from the repeated and focused interrogation of a group of individuals who are highly 366qualified and informed about a particular issue. Among the problems associated with this technique are:

identifying the appropriate pool of experts who represent the desired balance of opinions, philosophies, experience etc. (however, the membership of a professional organisation often provides a convenient participant pool)

convincing these experts to participate

obtaining panel feedback in a timely fashion

the assumption that participants are willing to have their judgements changed by exposure to judgements of other participants

panel attrition (tight time commitments are a common reason for this and the previous two problems)

misinterpretation of responses, e.g. ‘specious consensus’ caused by experts who conform in order to be left alone or because of participation fatigue

inability to obtain consensus or the temptation to ‘fit’ responses into a pattern of consensus (Garrod & Fyall 2005).

From a student perspective, few (if any) experts are likely to participate in a study that is not being sponsored and coordinated by a well-known professor or university, or lacks an incentive (e.g. privileged access to the results). Despite these pitfalls, the results can still be prophetic. One Delphi study undertaken in 1974 (Shafer & Moeller 1974) predicted that wildlife resources would be used mainly for nonconsumptive recreational uses such as photography by the year 2000, a forecast which has largely been realised through the growth of ecotourism (see chapter 11). More recently, the Delphi technique was used by Garrod (2003) to define ‘ecotourism’. This approach revealed consensus as to its core criteria, but exposed divisions as to the importance of local ownership, and the status of ecotourism as a process rather than just a type of tourism. Participating experts also tended to favour medium-length definitions that compromised between simplicity and comprehensiveness.

Observation

The collection of information through observation is warranted in many tourism-related research issues. Applications include:

noting the changing number and physical condition of hotels in a particular resort strip over a given period of time

recording the average length of time that visitors to a theme park have to wait in a queue before gaining entry, and noting their body language and other behaviour during the wait

counting the number of people who attend a major free entry event

identifying how people create and maintain their own personal space when spending time on a beach

observing where a hotel disposes of its garbage over a certain time period

recording the reaction of tourists towards souvenir hawkers at the entrance to a scenic site

following a tour group or individual tourists to observe their behaviour and spatial distribution in a duty-free shop.

In anthropological research, observation usually assumes that the humans being investigated are aware of and interact closely with the researcher who is trying to understand the subjects’ perspective. However, some efforts to observe the ‘unselfconscious’ behaviour of human subjects may involve attempts to remain undetected. Serious ethical questions are raised if this involves ‘stalking’ or the use of deception so that people are unaware that they are the subject of an investigation. The latter can 367occur in certain types of ‘participant observation’ research, as when the researcher temporarily assumes a certain false identity in order to gain access to the unselfconscious views and behaviour of the target group (Bowen 2002). For example, a researcher might work for several months among a group of lifeguards who assume that the researcher is ‘one of them’. In reality, the real intention of the researcher is to gain the confidence of the group so that the authentic behaviour and perceptions of the lifesaving subculture can be observed as part of a research project. Technologies such as webcams, RFID (see chapter 8) and GPS enhance the possibilities for observation-based research, but generate additional ethical and practical concerns.

Most universities maintain special committees that assess the ethical dimensions of such research and outline the conditions under which the projects are allowed to proceed. Because of the ethical questions raised and the amount of time involved, observation is not widely practised as a research technique within tourism studies despite its potential to yield knowledge that cannot be obtained as easily through survey or questionnaire-based methods.

Content analysis

Content analysis (CA) describes a variety of techniques used to systematically examine and measure the meaning of communicated material by classifying and evaluating selected words, themes or images (Hall & Valentin 2005). Four examples suffice to illustrate the varied use of CA within the contemporary tourism literature. First, Garrod (2008) had resident and tourist volunteers in a Welsh seaside resort take photographs of sites that were meaningful to them. The photographs were then content analysed and compared, revealing a high level of commonality in the meanings held by both groups. Second, Buckley (2008) analysed recent editions of the popular Lonely Planet guidebook series to assess whether the content was congruent with relevant academic theory, and found that the publication tended to reflect current social sustainability thinking more than the environmental perspective. Third, Govers, Go and Kumar (2007) analysed destination images by applying artificial neural network software to narratives solicited from a web-based survey. Finally, Shakeela and Weaver (2012) analysed the social media responses of Maldivian residents to a negative tourism incident posted on YouTube.

Secondary research

In secondary research, the investigator relies on material and research that has been compiled previously by other researchers. This substantially reduces the time and money required to obtain the desired information, especially given the availability of comprehensive and easily searched databases (such as www.leisuretourism.com) that contain a large number of secondary sources. However, a disadvantage is that users of this information cannot be entirely sure about its validity or reliability, since they were not involved in its original collection or compilation. Information sources that are important in secondary research are discussed as follows, and it should be noted that some primary research projects (e.g. Buckley 2008 and Shakeela & Weaver 2012 as previously described) use secondary material as their sources for generating primary data.

Academic journals

The proliferation of refereed journals within the field of tourism studies was discussed in chapter 1. Articles in academic journals, as described in that chapter, have the advantage of having undergone a double-blind reviewing process, which in theory increases the quality and objectivity of the published results. However, the time involved in 368undertaking the review process means that the results are often outdated by the time the article is released to the public, notwithstanding the time saved by the provision of pre-print online versions. In addition, refereed journals often tolerate tedious and technical writing styles that are not readily accessible to students, the tourism industry or even other academics. Proliferation itself is an emerging problem in the tourism field to the extent that there may not be enough quality manuscripts being submitted to sustain the many titles, forcing the editors of many of the newer journals in particular to accept mediocre manuscripts which would otherwise be rejected. Nevertheless, academic journals are a core source of secondary data for students and other researchers wishing to access research outcomes in all aspects of tourism. Good induction often occurs through the thorough and careful review of the academic journal literature on particular tourism topics.

Academic books

Academic books have also proliferated since the early 1990s. Although books usually undergo a less rigorous process of peer review, they are also generally subject to much less stringent page limitations, allowing for more in-depth analyses of particular issues. Increasingly, academic tourism books are edited compilations covering specific themes, in which individual authors or author teams prepare one or more chapters. The following are just a few of the edited academic books useful to researchers wishing to investigate specialised themes:

Frontiers in Nature-based Tourism: Lessons from Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden (Fredman & Tyrväinen 2012)

Philosophical Issues in Tourism (Tribe 2009)

Nautical Tourism (Lukovic 2013)

Dark Tourism and Place Identity: Managing and Interpreting Dark Places (White & Frew 2013)

The Business and Management of Ocean Cruises (Vogel, Papathanassis & Wolber 2011)

Journeys of Discovery in Volunteer Tourism: International Case Study Perspectives (Lyons & Wearing 2008)

Island Tourism: Sustainable Perspectives (Carlsen & Butler 2011)

Adventure Tourism: Meanings, Experiences and Learning (Taylor, Varley & Johnston 2013).

Statistical compilations

Tourism statistics are compiled by various government departments and nongovernmental organisations. Within Australia, Tourism Research Australia publishes a number of important compilations, including the International Visitor Survey and the National Visitor Survey (see the case study at the end of this chapter). The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) publishes Overseas Arrivals and Departures, which details the origins of inbound tourists and the destinations of outbound Australians. The ABS also publishes the Survey of Tourist Accommodation (STA), which is a quarterly Australia-wide survey of supply and demand for hotels containing at least 15 rooms. New Zealand is similarly comprehensive with regard to the regular serials that describe the development of its tourism sector, and is additionally innovative in making a large proportion of its tourism-related data publically accessible online.

Trade publications

Trade publications include paper magazines, online magazines and newsletters published by various industry organisations as well as government. As a source of data, they have the 369disadvantage of being ‘unscientific’ and journalistic in orientation. There is no equivalent of a double-blind review process, and the content often mirrors the vested interests and biases of the organisation producing the material. However, they are extremely useful for providing news of events that may have happened within the previous few weeks and indications of industry trends and perspectives. A prominent Australian trade publication relating to the tourism sector is Travel Weekly (www.TravelWeekly.com.au).

Newspapers and magazines

Newspapers and nonspecialised magazines such as Time and Newsweek (now usually available in abbreviated and/or augmented form on the internet) are subject to the same advantages and disadvantages as outlined for trade publications. Students should therefore be discerning and use these mainly as a source of current news, and also as a basis for content analysis exercises (i.e. a secondary source used to conduct primary analysis).

The internet

In addition to its increasingly important role as a medium for conducting primary research, the internet is now also a very popular source of secondary research information, especially as many of the previously mentioned publications are available online as a more accessible alternative to hard copy. While much reliable data can be obtained through the internet, quality and reputability are major issues that must be considered when using this source. The internet is an extremely attractive source of information for students as well as professional academics due to the convenience of being able to access an enormous amount of material on even the most obscure topics at a single computer terminal. An internet search, moreover, requires far less time to undertake than an exploration of conventional research sources. However, there are still no standards or controls that regulate material appearing on the internet (Wikipedia being a case in point), and the result is an enormous oversupply of useless, unreliable and misleading information that can overwhelm the reputable material.

THE RESEARCH PROCESS

THE RESEARCH PROCESS

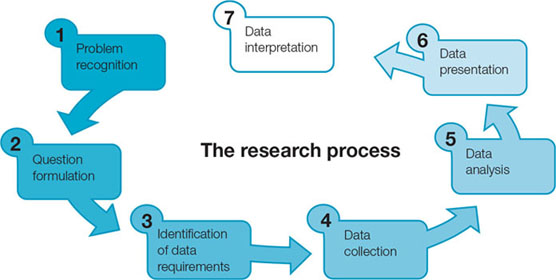

In order to produce substantive and useful outcomes, research must be carried out in a deliberate and systematic manner. The steps that are required to carry out a research project from its origins to its conclusions comprise the research process (see figure 12.4). The specific way in which each of these stages and their substages is operationalised will vary from project to project, and the process is seldom one that is strictly sequential. For example, the results from an analysis of data may prompt a rethinking of the original research questions. Alternatively, the research methods may have to be reconsidered once the researcher has begun to collect the data and discovers that in-depth interviewing would be more effective than an online survey in eliciting information from a particular group. More fundamentally, the methodological biases of the researcher often dictate, in the first instance, the problems that are identified and the questions that are posed.

Problem recognition

The first step in any research process is problem recognition, or the identification of the broad issues or problems that interest the investigator. For a tourism-based corporation, possible core issues that require research include declining market share, high employee turnover, and high levels of customer dissatisfaction. From a destination perspective, additional concerns may be harboured about negative community reactions 370to tourism or declining environmental conditions that both affect and are affected by tourism. Existing theories, such as the Butler sequence, may provide a useful framework for clarifying or contextualising the broad problem, which often emerges as a consequence of subjective perceptions, personal experiences or other qualitative input. As suggested earlier, methodological bias might dictate the problems that are identified. For example, a scientist trained in ‘hard’ quantitative techniques might not perceive relatively subjective issues such as cultural commodification or psychographic profiles (see chapter 9) as being amenable to or worthy of scientific analysis, and hence would not recognise them as problems that require a research agenda.

FIGURE 12.4 The research process

Question formulation

Once these broad problems or issues are identified, the research questions must be focused, at least in applied research, so that time and resources are not wasted on tangential or distracting avenues of investigation. As a basis for question formulation (which may be expressed as hypotheses or propositions), it is helpful to clarify the level of investigation that is warranted by the problem and the resources of the company or destination that are available. Four levels of investigation (description, explanation, prediction and prescription) are possible, each of which builds on the previous level.

Description

Description is the most basic level of inquiry. Imagine that the managers of a destination are concerned that local residents appear to be behaving in an increasingly hostile way towards schoolies during Schoolies Week. The logical first step in addressing this issue is to describe and clarify the actual situation. The following questions might be posed:

What are the attitudes of local residents towards schoolies and Schoolies Week?

How do these attitudes compare with past attitudes?

How do these attitudes vary within the local population?

Are the anti-schoolie sentiments more noticeable during Schoolies Week?

Are there particular locations within the destination where anti-schoolie sentiments are more noticeable?371

Explanation

The decision whether to proceed to the next level of investigation, which is to explain the resultant patterns, is often constrained by the availability of resources. However, the decision should be based on whether one or more serious problems have been revealed after the research process has been completed at the descriptive level. If it is found, for example, that the perceived hostility of residents involves only a few isolated incidents instigated by a few troublemakers, then there is probably no compelling reason to proceed any further with the collection of data. If, however, the suspicions of a broader hostility within the population have been confirmed, then explanation is a necessary stage towards its resolution. In the hypothetical Schoolies Week situation, the following explanation-based questions may emerge:

Why is a growing proportion of long-time residents in the community expressing increasingly hostile attitudes and unfriendly behaviour toward schoolies?

Why is most of the anti-schoolie behaviour occurring in Surfers Paradise and Broadbeach (an adjacent suburb)?

The subsequent research process might reveal that long-time residents remember when Schoolies Week involved only a few students and was not disruptive to residents. It also becomes apparent that Surfers Paradise is ground zero for Schoolies Week partying and that a spillover effect into Broadview has been occurring during the previous two years.

Prediction

Once plausible explanations for the problems are identified, the next level of investigation is to predict the consequences of the problem if no remedial measures are taken. As with any prediction involving people, this stage of inquiry is speculative and often begins with a process of extrapolation wherein past patterns are assumed to continue into the future. However, extrapolation must be qualified by intelligent and well-considered speculation and scenario-building that takes into account all available information, including the experience of similar destinations. Following on from the Schoolies Week example, the following predictive questions can be posed:

At what point and in what location is a serious confrontation (e.g. murder, riot) involving schoolies and locals likely to occur?

What will happen to the local tourism industry during and outside Schoolies Week if no steps are taken to address the growing hostility of some residents?

What will happen to the local community if nothing is done to contain troublemakers during Schoolies Week?

Prescription

Prescription is the culmination of the research process, involving the informed assessment of various solutions to minimise the problem. If the predictive phase reveals that the above situation is highly volatile, and that the community will endure great inconvenience if nothing is done, then the prescriptive phase will be essential. The following core question may emerge:

What steps can be taken before, during and after Schoolies Week to ensure that the situation does not escalate out of control?

Possible responses include increased policing of areas in Surfers Paradise where schoolies congregate, and a zero tolerance policy toward troublemakers.

The question of intervention, or the actions that should be taken to ensure optimum outcomes for the company or destination, is a core component of the management 372process, and a very important arena for applied research. However, appropriate solutions or prescriptions will only emerge as a result of the knowledge that is obtained through good preliminary research at the levels of description, explanation and prediction. In the aforementioned Schoolies Week example, to illustrate, it would be prudent and logical to interview a sample of past, present or future schoolies to gain their perspective. Furthermore, if the research questions raised at those levels are engaged effectively, it is more likely that problem areas will be intercepted and addressed before they evolve into major crises. Hence, it is difficult to see how good management can be undertaken in the absence of good research (see Managing tourism: Visitor tolerance levels at Victorian zoos).

managing tourism

![]() VISITOR TOLERANCE LEVELS AT VICTORIAN ZOOS

VISITOR TOLERANCE LEVELS AT VICTORIAN ZOOS

Werribee Open Range Zoo near Melbourne

Managers at zoos and wildlife parks are increasingly involved in pursuing sustainable outcomes by encouraging visitors to participate in pro-wildlife behaviour. However, at what point does solicitation to do so become a ‘turnoff’ or even harassment for visitors, and hence ineffectual? To address this issue, Smith and colleagues (2012) conducted research among visitors at the Melbourne Zoo and Werribee Open Range Zoo, which respectively attracted 1.14 million and 300 000 visitors in the 2010–11 reporting period. In the first of two studies, 162 visitors were asked to recall how many requests to sign a petition (for example, to free bears from slavery) were made during face-to-face presentations by keepers, and to provide the number of requests that they thought appropriate. On average, only 1.2 requests were recalled but 6.6 requests were considered appropriate. Only 2 per cent of the 162 participants indicated that their threshold of tolerance in this regard had been crossed during their visit. In the second study, 508 visitors were presented with a specific behaviour request (to purchase a Beads for Wildlife product made by poor communities in Kenya) and asked how often and where they had heard this during their current visit. Here, the respective figures were 1.7 requests recalled and 2.8 requests considered as the appropriate number; with 9 per cent declaring that too many requests were made. The tentative implication for zoo managers is that it may be better to make a variety of behaviour requests (e.g. a sequence of petitions for various causes) than to focus on a particular behaviour, although the research treated each request equally and did not take into account that short and subtle entreaties might produce a different response than ones that are prolonged and more direct.

Identification of research methodology or methods

The next stage usually involves the identification of the specific research methods that will best allow the questions to be addressed. This is usually informed by a search of secondary literature sources to see how other researchers in the past have approached similar problems. In the descriptive phase of the example used, the investigator may initially focus on observing tourist–schoolie interactions at a variety of locations and 373times during Schoolies Week. This can be augmented by quantitative surveying among residents and schoolies to provide a statistical basis for determining whether certain segments are more hostile towards schoolies than others. Depending on resources and time, observation and community focus groups may augment observation and surveying.

Cultural and social context must be considered in selecting an appropriate research methodology. For example, Likert-scaled survey questions (e.g. agreement with a statement on a 1 to 5 scale) are a reasonably effective means of eliciting accurate information from adults in mainstream, ‘Western’ societies such as those that predominate in Australia. However, there is evidence that East Asians for cultural reasons tend to avoid extreme responses on such instruments (i.e. they avoid ‘strongly’ agree or ‘strongly’ disagree options), even if this is the way they really feel about the situation. For research issues involving indigenous people, a standard quantitative methodology based on the scientific paradigm is often grossly inappropriate given the importance in those cultures of building trust through face-to-face contact over a long period. When interviewing local residents, it might be appropriate to employ trained locals rather than ‘outsiders’ who may be viewed with suspicion.

At the explanatory level, the researcher, in virtually any cultural context, should consider engaging in qualitative, in-depth interviews (e.g. with a sample of schoolies) to identify the reasons for revealed attitudes and behaviour. For prediction, the interviewer has a number of options that can be pursued in conjunction with each other to see whether the different methods yield the same results, or whether the outcomes can be combined to arrive at a probable scenario. These include:

an interview or survey question that asks residents what they are likely to do during the next Schoolies Week if the situation does not change

a modified Delphi technique to see what experts believe will occur

a literature review to identify the outcomes of similar situations in other destinations

extrapolation of past trends (e.g. if the number of hostile encounters has been increasing by 2 per cent a year over the past five years, then it could be assumed that this trend will continue to increase by a similar percentage in subsequent years).

To use all of these techniques in the same research process (whether at the explanatory or some other level of investigation) is to engage in methodological triangulation, or the use of several methods to gather information about and gain insight into the research issue (Belhassen & Santos 2006) (see also the ‘Contemporary issue: Qualitative reinforcement’ feature earlier in this chapter). If all of these four methods reveal similar outcomes, then the researcher can have a high degree of confidence that the real situation has been identified. Moreover, it is likely that each method will yield its own unique insights into this situation, thereby strengthening the knowledge base that is obtained from the research. Constraints of time, expertise and money, however, often rule out the use of triangulation.

At the prescriptive level, many approaches are also possible, including continued Delphi inquiries as to appropriate solutions, as well as solicitation of the community to see what local residents (and residents of Surfers Paradise and Broadbeach in particular) are willing to accommodate or suggest. Interviews with tourism managers in other destinations with similar experiences may also provide insight.

Data collection

Once the most appropriate methods have been identified, the data collection phase of the research process can proceed. In most cases, the researcher cannot access the entire population that is being investigated, or observe every event associated with a particular 374process. It is therefore expedient in such circumstances to select a sample from the target population. Sampling can be carried out on a probability or nonprobability basis. In the former case, a sample is randomly drawn from the population so that each member of that population has an equal or known probability of being selected. This can be done by simply drawing names out of a hat (in a small population), by using random number tables or selecting every nth name from a telephone directory or other source list.

However attained, it is important to select a large enough sample so that inferences can be made about the entire population within an acceptable margin of error. If carried out properly, a sample of 2000 households (or about 0.02 per cent) can accurately reflect all Australian households within a very small margin of error. However, for a population of around 1000, it is necessary to sample at least 30 per cent of that population to achieve the same effect, while a population of 100 would require a sample of around 80 per cent (Neuman 2010). Nonprobability or convenience sampling is commonly practised in qualitative research, and involves the deliberate selection of certain cases to build the sample. This type of sampling is not recommended for quantitative research except under special circumstances.

Once the sample size and selection procedure have been decided, the collection of data can begin. Factors that must be considered at this stage include the timing of interviews or observations, consistency in the application of the research method or methods, and the collection of all results in as short a time period as possible so that new developments do not skew the response patterns. Specific issues may have to be considered depending on the research method and the conditions that are encountered in the ‘field’. For example, telephone surveys carried out around dinner time are likely to yield a high potential response rate (i.e. people are likely to be at home), but a lower participation rate (i.e. because they do not wish to be bothered at that time).

Data analysis

The data analysis stage attempts to answer the relevant research questions by examining and assessing the collected information to identify patterns and meanings. Examination usually involves the filtering and organising of the database to eliminate invalid responses. This is then followed (mostly in quantitative research) by the coding and entering of the data into a computer software system such as SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences), which facilitates further classification and analysis. Once the data are ‘cleaned’ to eliminate errors in the coding procedure, the main analysis can be undertaken.

The most basic analysis in quantitative research is the recording of simple descriptive statistics such as frequencies, means and standard deviations (i.e. how much the data clusters around the mean). These are sufficient to answer many types of questions. At a more sophisticated level, tests of significance can be used to see whether the responses of one particular group are significantly different than those of the overall population or other specified subsections of that population. The relationships between many different variables and groups can be examined simultaneously using multivariate techniques such as factor analysis, cluster analysis and structural equation modelling (SEM). The level of sophistication that is appropriate depends on the nature of the research questions, the competency of the researcher and the characteristics of the data that are collected.

In qualitative research, analysis can involve the sorting, comparing, classifying and synthesis of the collected information, usually with a much higher level of subjective or personal judgement than occurs in quantitative analysis. Because of this subjectivity, qualitative researchers are more likely to practise triangulation.375

Data presentation

In the data presentation stage, the results of the analysis should be communicated in a way that can be easily interpreted by the target audience. Tables and graphs are the most common devices for presenting data, but great care should always be taken to avoid complexity and clutter, particularly if the intended audience is not academic. Confusion often results when researchers wrongly assume that the audience is familiar with specific techniques and jargon. In general, the reader should be able to read a table or figure on its own, so that the accompanying text can focus on analysis rather than description.

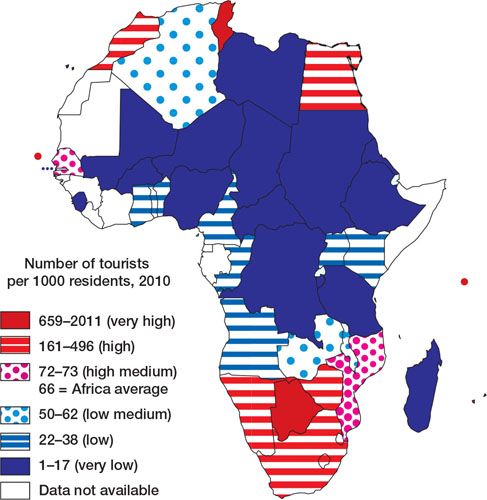

Maps are underused as a means of data presentation, even though they are an extremely efficient means of presenting spatial information if constructed properly. Imagine, for example, that the researcher wishes to examine patterns of tourism intensity in Africa relative to resident population. To identify this, figure 12.5 uses choropleth mapping — a technique which uses shading or patterns — to depict increasing (red) or decreasing (blue) levels of intensity relative to a given baseline (the average for all of Africa). In this case, intensity is measured as the number of inbound visitors to a country per 1000 residents in 2010. Almost instantaneously, the observer can appreciate the very low intensity that characterises middle Africa and the high intensity in the far north and south as well as offshore SISODs. Such a map is far more effective in conveying a pattern than a table or bar graph.

FIGURE 12.5 Effective cartography: Number of inbound visitors per 1000 residents of each country in Africa, 2010

Source: UN Statistical Division (2013), UNWTO (2012)

376

376

Data interpretation

The final stage, and in many ways the most difficult, is the extraction of meaning from the research results through data interpretation. This is where the significance and implications of the results are considered from a theoretical or practical perspective, or both. The researcher may consider higher levels of investigation at this stage (e.g. move from description to explanation), or may revisit previous stages. As with earlier stages in the research process, interpretation will be influenced by the methodological and other biases of the researcher. In quantitative research, the acceptance or rejection of a hypothesis at the previous stage is a more objective form of interpretation, since this is determined by the outcome of particular statistical applications. In such instances, the term ‘significance’ has a specific meaning — that is, the result of the technique tells us, for example, whether the difference between two populations is statistically significant within some specified margin of error. Interpretation may or may not in this case lead to broader and more subjective speculations about less tangible matters, such as the implications of these results for the community or company.

While it is possible for two researchers to produce almost identical results up to the point of hypothesis acceptance or rejection, it is likely that their interpretations of the results will differ at this broader level. Interpretation, in essence, can be as much an art as a science, and the effective interpreter is an individual who is well versed and experienced in the broader topic area and knowledgeable about the external environments that affect tourism. The importance of effective interpretation at the specific or broad level cannot be overstated, since this leads to the translation of research results into policy decisions and other outcomes that are important to the target audience.

377

CHAPTER REVIEW

The essential role of research is to provide a sound knowledge base that allows the managers of destinations and businesses to make the best possible planning and management decisions. Research can be categorised into several dichotomies. Basic research uses an inductive or deductive approach to broaden our understanding of tourism, while applied research is directed towards addressing a particular problem or issue. Cross-sectional research is undertaken during a single time period, while longitudinal research considers trends over two or more time periods in the past or future. Qualitative research tends to examine a small number of cases in great detail, while quantitative research usually considers a large number of cases in less depth. Finally, primary research occurs when investigators gather their own data, while secondary research involves the use of data that has already been gathered by other researchers.

The process through which research is undertaken comprises seven stages, although there is usually considerable flexibility in the sequence of steps that are actually followed in a research project. The process begins with problem recognition, and proceeds to the formulation of questions or hypotheses that provide a specific focus for investigation. At this point, the researcher also needs to consider the level of investigation that is of interest — description, explanation, prediction or prescription. Subsequently, a methodology (if not predetermined) and methods must be selected that address the research questions, and data collected that can then be analysed using those techniques. Once the data have been presented, the research process culminates in the interpretation of the results, which allows these to be translated into usable outcomes by the target audience.

SUMMARY OF KEY TERMS

SUMMARY OF KEY TERMS

Applied research research that addresses some particular problem or attempts to achieve a particular set of outcomes; it is usually constrained by set time schedules

Autoethnography a form of qualitative research in which the researcher positions herself or himself as a subject of investigation

Basic research research that is broadly focused on the revelation of new knowledge, and is not directed towards specific outcomes or problems

Cross-sectional research a ‘snapshot’ approach to research that considers one or more sites at one particular point in time

Data analysis the process by which the collected information is examined and assessed to identify patterns that address the research questions

Data collection the gathering of relevant information by way of the techniques identified in the research methodology stage

Data interpretation the stage during which meaning is extracted from the data

Data presentation the stage during which the results of the analysis are communicated to the target audience

Deduction an approach in basic research that begins with a basic theory that is applied to a set of data to see whether the theory is applicable or not

Hypotheses tentative informed statements about the nature of reality that can be subsequently verified or rejected through systematic deductive research

Induction an approach in basic research whereby the observation and analysis of data leads to the formulation of theories or models that link these observations in a meaningful way378

Longitudinal research a trends-oriented approach to research, which examines one or more sites at two or more points in time or, more rarely, on a continuous basis

Primary research research that involves the collection of original data by the researcher

Problem recognition the first stage of the research process, which is the identification of a broad problem arena that requires investigation

Qualitative research research that does not place its emphasis on the collection and analysis of statistical data, and usually tends to obtain in-depth insight into a relatively small number of respondents or observations

Quantitative research research that is based mainly on the collection and analysis of statistical data, and hence tends to obtain a limited amount of information on a large number of respondents or observations; these results are then extrapolated to the wider population of the subject matter

Question formulation the posing of specific questions or hypotheses that serve to focus the research agenda arising from problem recognition; these questions can be descriptive, explanatory, predictive or prescriptive in nature

Research a systematic search for knowledge

Research methodology a set of assumptions, procedures and methods that are used to carry out a search for knowledge within a particular type of research

Research methods the techniques that will be used to answer the questions or prove or disprove the hypotheses

Research process the sequence of stages that are followed to carry out a research project from its origins to its conclusions

Secondary research research in which the investigator uses previously collected data

Triangulation the use of multiple methods, data sources, investigators or theories in a single research process

QUESTIONS

QUESTIONS

From a corporate perspective, what are the advantages and disadvantages of pursuing basic (as opposed to applied) research?

-

What is the difference between induction and deduction?

How do the two approaches work together in long-term research projects?

Why is cross-sectional research carried out infrequently?

-

What are the relative strengths and weaknesses of:

qualitative research, and

quantitative research?

In what ways can qualitative and quantitative research display a complementary relationship?

What problems are potentially encountered when using observation as a means of gathering primary data about people?

-

What are the strengths and weaknesses of web-based surveys as compared to postal surveys?

Under what conditions is each the most appropriate method of surveying?

When interviewing local residents, what are the advantages and disadvantages respectively of having other local residents or outside academics conduct the interviews?

What is methodological triangulation and why is it considered desirable?

379Why is a sampling rate of 80 per cent appropriate to represent a population of 100 individuals, but just 0.02 per cent for a population of 20 million individuals?

-

Why can interpretation be considered an art as much as a science?

How important is interpretation to the research process?

EXERCISES

EXERCISES

For each of the following destination or business management scenarios, write a 200-word report in which you list the data you would collect, and describe how you would collect and analyse these data.

The Gold Coast is planning on building a major cruise ship terminal on The Spit, an area of sand dunes near the mouth of the Nerang River. Will local residents support this project?

An ecolodge has been given permission to establish accommodation in the Tasmanian World Heritage listed wilderness, on the condition that it causes no significant harm to the environment. What type of accommodation and location will best meet this condition?

A major downtown hotel in Beijing, to show its environmental credentials, has held EarthCheck Platinum status for the past two years. Many shareholders in the hotel, however, are concerned that this is not a financially sound decision. Is it wise to maintain this certification status? Why?

The destination marketing organisation for Australia has just been given a 25 per cent cut in its budget, and must close 4 of its 16 (hypothetical) offices in Asia (Bangkok, Beijing, Chennai, Chongqing, Hong Kong, Jakarta, Kuala Lumpur, Manila, Mumbai, New Delhi, Osaka, Seoul, Shanghai, Singapore, Taipei and Tokyo). Which 4 offices should be closed? Explain your reasons.

-

Using any recent article from Annals of Tourism Research, Tourism Management or the Journal of Travel Research, identify the type of research that is represented and the type of primary and/or secondary research methods and sources that are employed.

Describe how these types of research and methods are related to the problem recognition, question formulation and identification of data requirements (i.e. first three stages of the research process in the final section of this chapter) used in the article.

FURTHER READING

FURTHER READING

Fowler, F. 2009. Survey Research Methods. Fourth Edition. New York: Sage. Web-based surveys and the use of mobile phones as survey media are among the contemporary surveying issues discussed in this textbook, which also focuses on data analysis.

Goodson, L. & Phillimore, J. (Eds) 2004. Qualitative Research in Tourism: Ontologies, Epistemologies and Methodologies. London: Routledge. This book provides a comprehensive exposure to and analysis of qualitative research methods as they pertain to the tourism sector.

Jennings, G. 2010. Tourism Research. Second Edition. Brisbane: John Wiley & Sons. Jennings discusses all essential aspects of research from a tourism studies perspective, including data sources, ethical considerations, qualitative and quantative methods, and the preparation of research proposals.

Neuman, W. L. 2010. Social Research Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. Seventh Edition. London: Allyn and Bacon. A comprehensive 380discussion of the application of research methods to social phenomena is provided in this popular general textbook.

Ritchie, B., Burns, P. & Palmer, C. (Eds) 2005. Tourism Research Methods: Integrating Theory with Practice. Wallingford, UK: CABI. The 17 chapters in this collection encompass a comprehensive array of research issues and methods, including longitudinal research, participant observation, qualitative research, and content analysis.

case study

![]() BUILDING KNOWLEDGE CAPACITY THROUGH TOURISM RESEARCH AUSTRALIA

BUILDING KNOWLEDGE CAPACITY THROUGH TOURISM RESEARCH AUSTRALIA

National-level tourism research, although widely acknowledged as critical to Australia’s competitiveness as a destination, is an example of a service that individual private businesses are usually reluctant to pay for because it also benefits competing businesses. To address the resulting market failure — that is, the failure to conduct vital research about tourism in Australia — the Department of Resources, Energy and Tourism established a dedicated entity, Tourism Research Australia (TRA), to conduct such macro-level research. At the broadest level, the TRA is mandated to provide relevant and timely knowledge for Australia’s tourism industry that helps to meet the government’s goal of maximising tourism’s contribution to the national economy within a context of environmental and social sustainability. To this effect, the TRA provides statistics, research and analysis in support of industry and product development, policy development, and marketing of tourism products and businesses.

Among the best known and most referenced TRA research outputs are the quarterly national surveys of international and domestic tourists. The International Visitor Survey (IVS) is based on face-to-face interviews with 40 000 departing short-term international visitors aged 15 or older (TRA 2013). These interviews are conducted over the course of the year at major international airports, and solicit such critical information as country of residence, expenditures (amount and by category), demographic characteristics, purpose of visit, transport and accommodation, activities, travel party, information sources, and places visited. The National Visitor Survey (NVS) uses a computer-assisted telephone interviewing system to each year interview 120 000 Australian residents aged 15 or older. The solicited data is similar to the IVS, and both surveys are jointly funded by the federal and state governments. A third type of data collection, the Destination Visitor Survey (DVS), focuses on specific regions or places that are selected for scrutiny in collaboration with state tourism organisations.

381Beyond the intrinsic knowledge about Australian tourism that they reveal, data generated from the IVS and NVS are used by the TRA to make performance forecasts for tourist numbers and expenditures, usually over a 10-year time frame. They also contribute to the calculation of tourism satellite accounts and modelling for regional expenditure and economic value. An important publication that collates and synthesises all these findings is the annual ‘State of the Industry’ report. The 2012 version (TRA 2012) summarises the sector’s performance and underlying factors, and uses the Tourism Scorecard as a way of tracking this performance in the context of goals set forth in the organisation’s Tourism 2020 long-term strategy. These goals are based on the ‘hard’ economic criteria of increased aviation capacity, revenue growth, and increased supply of visitor accommodations.

Acknowledging the diversity of Australia’s tourism stakeholders, the TRA also provides ‘snapshots’ and fact sheets about specific sectors (e.g. business events, cultural and heritage tourism, food and wine tourism, Indigenous tourism, and nature-based tourism), markets (e.g. inbound Chinese, backpackers, mature age visitors), products (e.g. caravans, bed & breakfast accommodation) and issues (e.g. impact of the mining boom on tourism, internet use in trip planning and booking). It also accommodates customised requests for specific data outputs on a fee-paying basis, and maintains a subscription service that allows members to access, select and statistically manipulate online data however they wish. Member access to new data is immediate, customised tables can be stored and updated, and both face-to-face and online training sessions are available along with help desk assistance during business hours. Online access to the IVS and NVS is also available to students through subscribing educational institutions.