The tourism system

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

describe the fundamental structure of a tourism system

assess the external forces that influence and are influenced by tourism systems

outline the three criteria that collectively define tourists

explain the various purposes for tourism-related travel, and the relative importance of each

identify the four major types of tourist and the criteria that apply to each

evaluate the importance of origin and transit regions within the tourism system

explain the role of destination regions and the tourism industry within the tourism system.

20

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

The introductory chapter defined tourism and described the development of tourism as a widespread area of focus within the university system, despite lingering prejudices. This is indicated by the large number of tourism-related programs and refereed journals as well as the movement towards a more objective knowledge-based philosophy that recognises tourism as a complex system requiring scientific investigation.

Chapter 2 discusses the concept of the tourism system and introduces its key components, thereby establishing the basis for further analysis of tourism system dynamics in subsequent chapters. The following section outlines the systems-based approach and presents tourism within this context. The subsequent ‘The tourist’ section defines the various types of tourist, considers the travel purposes that qualify as tourism and discusses problems associated with these definitions and the associated data. The origin regions of tourists are considered in the ‘Origin region’ section, while transit and destination regions are discussed in ‘Transit region’ and ‘Destination region’ sections, respectively. The industry component of the tourism system is introduced in the final section.

A SYSTEMS APPROACH TO TOURISM

A SYSTEMS APPROACH TO TOURISM

A system is a group of interrelated, interdependent and interacting elements that together form a single functional structure. Systems theory emerged in the 1930s to clarify and organise complex phenomena that are otherwise too difficult to describe or analyse (Leiper 2004). Systems tend to be hierarchical, in that they consist of subsystems and are themselves part of larger structures. For example, a human body comprises digestive, reproductive and other subsystems, while human beings themselves are members of broader social systems (e.g. families, clans, nations). Systems also involve flows and exchanges of energy which almost always involve interaction with external systems (e.g. a human fishing or hunting for food). Implicit in the definition of a system is the idea of interdependence, that is, that a change in a given component will affect other components of that system. To examine a phenomenon as a system, therefore, is to adopt an integrated or holistic approach to the subject matter that transcends any particular discipline — in essence, an interdisciplinary or postdisciplinary approach that complements the knowledge-based platform (see chapter 1).

The basic whole tourism system

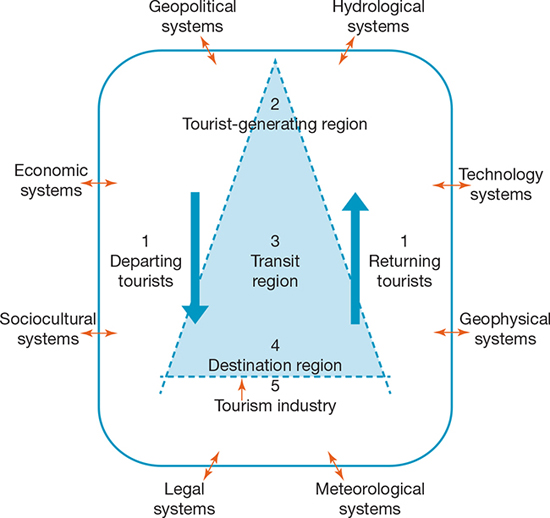

Attempts have been made since the 1960s to analyse tourism from a systems approach, based on the realisation that tourism is a complex phenomenon that involves interdependencies, energy flows and interactions with other systems. Leiper’s basic whole tourism system (Leiper 2004) places tourism within a framework that minimally requires five interdependent core elements:

at least one tourist

at least one tourist-generating region

at least one transit route region

at least one tourist destination

a travel and tourism industry that facilitates movement within the system (see figure 2.1).

The movement of tourists between residence and a destination, by way of a transit region, and within the destination, comprises the primary flow of energy within this system. Other flows of energy include exchanges of goods (e.g. imported food to feed tourists) and information (e.g. tourism-related social media exchanges) that involve an array of interdependent external environments and systems in which the tourism system is embedded. The experience of the tourist, for example, is facilitated (or impeded) by the economic and geopolitical systems which, respectively, provide or do not provide sufficient discretionary income and accessibility to make the experience possible. Natural and cultural external factors can have dramatic and unpredictable effects on tourism systems, as illustrated by the Indian Ocean tsunami of 26 December 2004. This event killed an estimated 200 000 local residents and tourists, and devastated destinations throughout the Indian Ocean basin. Tourism businesses in heavily affected destinations — such as the popular Thai seaside resort province of Phuket — were forced to adjust, and some were able to demonstrate greater resilience than others (see the case study at the end of this chapter). Within Australia, various external (nontourism) factors during the early twenty-first century, including a high Australian dollar, the persistent global financial crisis, and increasing fuel costs, have combined to seriously harm the domestic and inbound tourism systems.

Tourism systems in turn influence these external environments, for example by stimulating a destination’s economy (see chapter 8) or helping to improve relations between countries (see chapters 9 and 11). Following the 2004 tsunami, a high priority was placed by affected destination governments and international relief agencies on restoring international tourist intakes, on the premise that this was the most effective way of bringing about a broader and more rapid economic and 22psychological recovery (Henderson 2007). Despite such critical two-way influences, there is a tendency in some tourism system configurations to ignore or gloss over the external environment, as if tourism were somehow a self-contained or closed system.

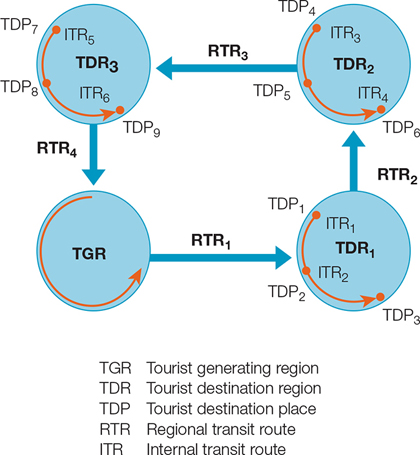

The internal structure of the tourism system is also far more complex than implied by figure 2.1, thereby presenting more challenges to the effective management of tourism. Many tourist flows are actually hierarchical in nature, in that they involve multiple, nested and overlapping destinations and transit regions (see figure 2.2). Take, for example, a Canadian from Vancouver who travels across the Pacific Ocean (‘regional transit route’) to visit Australia (‘tourist destination region’) and then spends time in Sydney, Uluru and the Whitsundays (i.e. three ‘tourist destination places’), travelling between them along various ‘internal transit routes’. Cumulatively, the global tourism system encompasses an immense number of individual experiences and bilateral or multilateral flows involving thousands of destinations at the international and domestic level. Regarding the stakeholders depicted in figure 1.1, the tourists and the tourism businesses (or tourism industry) are present throughout Leiper’s tourism system (figure 2.1), as are nongovernmental organisations (NGOs) and educational institutions. However, tourism businesses are mostly concentrated in destination regions, with transit and origin regions respectively less well represented, as indicated by the triangle in figure 2.1. Host governments and communities are by definition located in the destination region, while origin governments are situated clearly in the tourist-generating region.

FIGURE 2.2 Tourism system with multiple transit and destination components

Source: Adapted from Leiper (2004)

Finally, the overall tourism system is a hyperdynamic structure that is in a constant state of flux. This is apparent not only in the constant travel of millions of tourists, but also in the continuous opening and closing of accommodation facilities 23and transportation routes across the globe. This instability represents yet another challenge faced by tourism managers, who must realise that even the most up-to-date profile of the sector soon becomes obsolete. The only certainty in tourism systems is constant change.

THE TOURIST

THE TOURIST

As suggested in chapter 1, the definition of tourism is dependent on the definition of the tourist. It is therefore critical to address this issue in a satisfactory way before any further discussion of management-related issues can take place. Every tourist must simultaneously meet certain spatial, temporal and purposive criteria, as discussed below.

Spatial component

To become a tourist, a person must travel away from home. However, not all such travel qualifies as tourism. The World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) and most national and subnational tourism bodies hold that the travel must occur beyond the individual’s ‘usual environment’. Since this is a highly subjective term that is open to interpretation, these bodies normally stipulate minimum distance thresholds, or other criteria such as state or municipal residency, which distinguish the ‘usual environment’ from a tourist destination (see the ‘Data problems’ section). The designation and use of such thresholds may appear arbitrary, but they serve the useful purpose, among others, of differentiating those who bring outside revenue into the local area (and thereby increase the potential for the generation of additional wealth) from those who circulate revenue internally and thereby do not create such an effect.

Domestic and international tourism

If qualifying travel occurs beyond a person’s usual environment but within his or her usual country of residence, then that individual would be classified as a domestic tourist. If the experience occurs outside of the usual country of residence, then that person would be classified as an international tourist. The concept of ‘usual environment’ does not normally apply in international tourism. Residents of a border town, for example, become international tourists as soon as they cross the nearby international border (providing that the necessary temporal and purposive criteria are also met). An aspect of international tourism that is seldom recognised is the fact that such travel always involves some movement within the international tourist’s own country — for example, the trip from home to the airport or international border. Although neglected as a subject of research, this component is nonetheless important, because of the infrastructure and services that are used and the economic activity that is generated. Vehicles queued for a kilometre or more waiting to cross from Singapore to Malaysia attest to this influence.

International tourism differs from domestic tourism in other crucial respects. First, despite the massive volume of international tourism (See Breakthrough tourism: Breaking the billion barrier), domestic tourists far outnumber international tourists on a global scale and within all but the poorest countries. In Australia, for example, Australian residents aged 15 or older accounted for 74.7 million trips within Australia between 1 October 2011 and 30 September 2012 (TRA 2012a), compared with 5.6 million trips by international tourists (TRA 2012b).

24

![]() BREAKING THE BILLION BARRIER

BREAKING THE BILLION BARRIER

In 2012, for the first time, more than one billion international stayovers were recorded from the cumulative reports of the UNWTO member states. There was speculation in the late 1990s that this threshold would be reached much earlier, but the global financial crisis (GFC) of 2008 and onward effectively depressed global visitation growth. The number, in itself, is not especially significant in a practical sense, since the previous year’s total of 980 million is not much smaller. However, the one billion threshold has great symbolic value in conveying to a largely unaware public the impressive magnitude of the global tourism system and its potential as a tool for development — or the potential for negative environmental and social impacts if not managed effectively. The UNWTO did not fail to capitalise on the attendant marketing opportunities, selecting a British tourist’s arrival in Madrid on 13 December as the symbolic and much-publicised one billionth tourist. The popular online site CNN Travel provided strong coverage of this event and related developments, including a UNWTO infographic that summarised basic patterns of origin, destination and purpose (CNN 2012). The milestone was also leveraged in the UNWTO’s ‘One billion tourists: One billion opportunities’ media campaign, which made the point that an environmental or social contribution from every tourist, however modest, produces an enormously positive cumulative effect. Specifically, based on the campaign website’s public poll, ‘buying local’ was voted the most popular suggestion for action, followed by ‘respecting local cultures’, ‘protecting heritage’, ‘saving energy’ and ‘using public transport’. Concurrently, a ‘Faces of the one billion’ campaign was launched in which tourists travelling internationally were invited to submit a photo of themselves in front of a favourite tourist attraction. These were then posted on the UNWTO Facebook page, thereby giving a sense of individuality and dynamism to the ‘one billion’ figure (UNWTO 2012a).

Second, relatively little is known about domestic tourists compared with their international counterparts, despite their numbers and economic importance. One reason is that most national governments do not consider domestic tourists to be as worthy of scrutiny, since they do not bring much-valued foreign exchange into the country but ‘merely’ redistribute wealth from one part of the country to another. It is often only when international tourist numbers are declining, for example in the aftermath of the Indian Ocean tsunami of 2004, that governments are prompted to support local tourism businesses by promoting their domestic tourism sector. Another reason for the relative neglect is that domestic tourists are usually more difficult to count than international tourists, since they are not subject, in democratic countries at least, to the formalities faced by most international tourists, such as having a passport scanned. However, where countries are moving towards political and economic integration, and hence more open borders, international tourist flows are becoming just as difficult to monitor as domestic flows. This is well illustrated at present by the 28 countries of the ever-enlarging European Union (see chapter 4).

25Finally, there are some cases where the distinction between domestic and international tourism is not entirely clear. This occurs when the tourism system incorporates geopolitical entities that are not part of a fully fledged country. For example, should a Palestinian resident of the Israeli-controlled West Bank be considered an international or domestic tourist during travel to Israel? Travel between the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region and China is another ambiguous situation, as is travel between Taiwan and mainland China. Australians travelling to Norfolk Island are subject to full immigration controls, even though this destination is a self-governing external territory of Australia.

Outbound and inbound tourists

When referring specifically to international tourism, a distinction is made between outbound tourists (those leaving their usual country of residence) and inbound tourists (those arriving in a country different from their usual country of residence). Any international tourism trip has both outbound and inbound components, with the distinction being based on whether the classification is being made from the perspective of the country of origin or destination. Take, for example, a New Zealander who spends two weeks on holiday in Thailand. This person would be considered outbound from a New Zealand perspective (i.e. an ‘outbound New Zealander’) but inbound from the Thai perspective (i.e. an ‘inbound New Zealander’).

During any year, the cumulative number of inbound trips will always exceed the total number of outbound trips on a global scale, since one outbound trip must translate into at least, but possibly more than, one inbound trip. This is demonstrated by the hypothetical example of an Australian tourist who visits five countries during a trip to South-East Asia. From Australia’s perspective, this trip equates to one outbound Australian tourist experience. However, each of the Asian countries will record that traveller as one inbound Australian tourist, resulting in five separate instances of inbound Australian tourism. Some origin governments require returning outbound tourists to report all visited destination countries, while others do not. Australia, for example, requires returning tourists to designate the one country where they spent most of their time abroad during that particular trip.

Long-haul and short-haul travel

A distinction can be made between long-haul tourists and short-haul tourists. There are no universal definitions for these terms, which are often defined according to the needs and purposes of different organisations, sectors or destinations. The UNWTO regards long-haul travel as trips outside the multi-country region in which the traveller lives (UNWTO 2011). Thus, a United Kingdom resident travelling to Germany (i.e. within Europe, the same region) is a short-haul tourist, while the same resident travelling to South Africa or Australia is a long-haul tourist. Airlines usually base the distinction on distance or time thresholds, 3000 miles (6600 kilometres) or five hours commonly being used as a basis for differentiation (Lo & Lam 2004). One implication is that long-haul routes require different types of aircraft and passenger management strategies. Diabetics travelling on long-haul flights, for example, are more likely than those on short-haul flights to experience diabetes-related problems while in flight, though the actual number of those having problems is small (Burnett 2006). From a destination perspective, long-haul tourists are often distinguished from short-haul tourists by expenditure patterns, length of stay and other critical parameters. They may as a result also warrant separate marketing and management strategies.26

Temporal component

The length of time involved in the trip experience is the second basic factor that determines whether someone is a tourist and what type of tourist they are. Theoretically, while there is no minimum time that must be expended, most trips that meet domestic tourism distance thresholds will require at least a few hours. At the other end of the time spectrum, most countries adhere to a UNWTO threshold of one year as the maximum amount of time that an inbound tourist can remain in the visited country and still be considered a tourist. For domestic tourists such thresholds are less commonly applied or monitored. Once these upper thresholds are exceeded, the visitor is no longer classified as a tourist, and should be reassigned to a more appropriate category such as ‘temporary resident’ or ‘migrant’.

Stayovers and excursionists

Within these time limits, the experience of an overnight stay is critical in defining the type of tourist. If the tourist (domestic or international) remains in the destination for at least one night, then that person is commonly classified as a stayover. If the trip does not incorporate at least one overnight stay, then the term excursionist is often used. The definition of an ‘overnight stay’ may pose a problem, as in the case of someone arriving at a destination at 2.00 am and departing at 4.00 am. However, ambiguous examples such as this one are rare, and the use of an overnight stay criterion is a significant improvement over the former standard of a minimum 24-hour stay, which proved both arbitrary and extremely difficult to apply, given that it would require painstaking monitoring of exact times of arrival and departure.

Excursion-based tourism is dominated by two main types of activity. Cruise ship excursionists are among the fastest growing segments of the tourist market, numbering 16.3 million in 2011 (CLIA 2012) but many more if quantified as inbound tourists from the cumulative perspective of each cruise ship destination country. Certain geographically suitable regions, such as the Caribbean and Mediterranean basins, are especially impacted by the cruise ship sector, which is expected to increase its capacity from 325 000 beds in 2011 to 361 000 beds in 2015 (CLIA 2012). The Australia/New Zealand/South Pacific region, by contrast, accounts for just 2.7 per cent of all ‘bed days’ due to its relatively small population and geographic isolation. Cross-border shoppers are the other major type of excursionist. This form of tourism is also spatially concentrated, with major flows being associated with adjacent and accessible countries with large concentrations of population along the border. Examples include Canada/United States, United States/Mexico, Singapore/Malaysia, Argentina/Uruguay and western Europe. However, this is a very unusual phenomenon for Australia because of its insularity and isolation.

As with domestic tourists and other domestic travellers, the distinction between stayovers and excursionists is more than a bureaucratic indulgence. Significant differences in the management of tourism systems are likely depending on whether the tourism sector is dominated by one or the other group. An important difference, for example, is the excursionists’ lack of need for overnight accommodation in a destination.

Travel purpose

The third basic tourist criterion concerns the travel purpose, which should not be confused with motivation. Not all purposes for travelling qualify as tourism. According to the UNWTO, major exclusions include travel by active military personnel, daily routine trips, commuter traffic, migrant and guest worker flows, nomadic movements, 27refugee arrivals and travel by diplomats and consular representatives. The latter exclusion is related to the fact that embassies and consulates are technically considered to be part of the sovereign territory of the country they represent. The purposes that do qualify as tourism are dominated by three major categories:

leisure and recreation

visiting friends and relatives

business.

Leisure and recreation

Leisure and recreation are just two components within a constellation of related purposes that also includes terms such as ‘vacation’, ‘rest and relaxation’, ‘pleasure’ and ‘holiday’. This is the category that usually comes to mind when the stereotypical tourism experience is imagined. Leisure and recreation account for the largest single share of tourist activity at a global level. As depicted in table 2.1, this also pertains to Australia, where ‘holiday’ (the Australian version of the category) constitutes the main single purpose of visits for both domestic and inbound tourists.

Visiting friends and relatives (VFR)

The intent to visit friends and relatives (i.e. VFR tourism) is the second most important purpose for domestic and inbound tourists in Australia (table 2.1). Backer (2012), however, maintains that the actual magnitude of VFR is underestimated because many tourists staying with friends or family list ‘holiday’ as their purpose. An important management implication of VFR tourism is that, unlike pleasure travel, the destination decision is normally predetermined by the destination of residence of the person who is to be visited. Thus, while the tourism literature emphasises destination choice and the various factors that influence that choice (see chapter 6), the reality is that genuinely ‘free’ choice only exists for pleasure-oriented tourists. Another interesting observation is the affiliation of VFR-dominated tourism systems with migration systems. About one-half of all inbound visitors to Australia from the United Kingdom, for example, list VFR as their primary purpose (as opposed to about one-fifth of inbound tourists in total), and this over-representation is due largely to the continuing importance of the United Kingdom as a source of migrants.

TABLE 2.1 Main reason for trip by inbound and domestic visitors, Australia, 2011/12

Source: TRA (2012a, 2012b)

Business

Business is roughly equal to VFR as a reason for tourism-related travel at a global level. Even more so than with the VFR category, business tourists are constrained in their travel decisions by the nature of the business that they are required to undertake. Assuming that the appropriate spatial and temporal criteria are met, business travel is 28a form of tourism only if the traveller is not paid by a source based in the destination. For example, a consultant who travels from Sydney to Melbourne, and is paid by a company based in Melbourne, would not be considered a tourist. However, if payment is made by a Sydney-based company, then the consultant is classified as a tourist. This stipulation prevents longer commutes to work from being incorporated into tourism statistics, and once again reflects the principle that tourism involves the input of new money from external sources.

There are numerous subcategories associated with business tourism, including consulting, sales, operations, management and maintenance. However, the largest category involves meetings, incentive travel, conventions and exhibitions, all of which are combined in the acronym MICE. Most, but not all, of MICE tourism is related to business. Many meetings and conventions, for example, involve such non-business social activities as school and military reunions. Similarly, exhibitions can be divided into trade and consumer subtypes, with the latter involving participants who attend such events for pleasure/leisure purposes. Incentive tourists are travellers whose trips are paid for all or in part by their employer as a way of rewarding excellent employee performance. In the period from 1 November 2011 to 31 October 2012, 188 400 inbound visitors arrived in Australia to attend conferences or conventions, or about 4 per cent of the total intake (Business Events Australia 2012).

Sport

Several additional purposes that qualify a traveller as a tourist are less numerically important than the three largest categories outlined previously, though more important in certain destinations or regions. Sport-related tourism involves the travel and activities of athletes, trainers and others associated with competitions and training, as well as the tourist spectators attending sporting events and other sport-related venues. High-profile sporting mega-events such as the Olympic Games and the World Cup of football not only confer a large amount of visibility on the host destination and participating teams, but also involve many participants and generate substantial tourist expenditure and other ‘spin-off’ effects. Sporting competitions in some cases have also been used to promote cross-cultural understanding and peaceful relations between countries and cultures (see chapters 9 and 11).

Spirituality

Spiritual motivation includes travel for religious purposes. Pilgrimage activity constitutes by far the largest form of tourism travel in Saudi Arabia due to the annual pilgrimage or Hajj to Mecca by several million Muslims from around the world. Religious travel is also extremely important in India’s domestic tourism sector, accounting for about 170 million visits per year or at least 70 per cent of all domestic tourism (Shinde 2010, 2012). One festival alone, the six-week Maha Kumbh Mela, drew an estimated 100 million Hindu pilgrims to the city of Allahabad in 2013. It is commonly regarded as the world’s biggest event of any type.

More ambiguous is the secular pilgrimage, which blurs the boundary between the sacred and the profane (Digance 2003). The term has been applied to diverse tourist experiences, including commemorative ANZAC events at the Gallipoli battle site in Turkey (Hyde & Harman 2011), as well as visits to Olympic sites (Norman & Cusack, 2012). Secular pilgrimage is often associated with the New Age movement, which is variably described as a legitimate or pseudoreligious phenomenon. Digance (2003) describes how the central Australian Uluru monolith has become a contested sacred site, in part because of conflicts between Aboriginal and New Age pilgrims seeking privileged access to the site.29

Health

Tourism for health purposes includes visits to spas, although such travel is often merged with pleasure/leisure motivations (see chapter 3). More explicitly health related is travel undertaken to receive medical treatment that is unavailable or too expensive in the participant’s home country or region. Such travel is often described as medical tourism (Chambers & McIntosh 2008). Cuba, for example, has developed a specialty in providing low-cost surgery for foreign clients. In Australia, the Gold Coast of Queensland is building a reputation as a centre for cosmetic surgery and other elective medical procedures, in many cases for patients from the Middle East. Many Americans travel to Mexico to gain access to unconventional treatments that are unavailable in the United States.

Study

Study, and formal education more broadly, is a category that most people do not intuitively associate with tourism, even though it is a qualifying UNWTO criterion. Australia, New Zealand, Canada, the United States and the United Kingdom are especially active in attracting foreign students. Although participant numbers may not appear large in relation to the three main categories of purpose, students have a substantial relative impact on host countries because of the prolonged nature of their stay and the large expenditures (including tuition) that they make during these periods of study. For example, international students accounted for about 6 per cent of all inbound arrivals to Australia in 2011–12 but 25 per cent of all visitor-nights, due to an average length of stay of 142 nights. Accordingly, the average expenditure in Australia by international students was $16 027, compared with $3341 for inbound tourists overall (TRA 2012b). Foreign students also benefit Australia by attracting visitors from their home country during their period of study, spending money in regional cities such as Ballarat and Albury that otherwise attract few international tourists. They also often return to their country of study as leisure tourists or permanent migrants.

Multipurpose tourism

If every tourist had only a single reason for travelling, the classification of tourists by purpose would be a simple task. However, many if not most tourist trips involve multipurpose travel, which can be confusing for data classification and analysis. The current Australian situation illustrates the problem. Departing visitors are asked to state their subsidiary travel purposes as well as their primary purpose for travelling to Australia. It is on the basis of the primary purpose alone that table 2.1 is derived, and policy and management decisions subsequently made. These data, however, may not accurately reflect the actual experiences of the tourists.

Take, for example, a hypothetical inbound tourist who, at the conclusion of a two-week visit, states ‘business’ as the primary trip purpose, and pleasure/holiday and VFR as other purposes. The actual trip of that business tourist may have consisted of conference attendance in Sydney over a three-day period, a three-day visit with friends in the nearby town of Bathurst and the remaining eight days at a resort in Port Douglas. While the primary purpose was business, this is clearly not reflected in the amount of time (and probably expenditure) that the tourist spent on each category of purpose. Yet without the conference, the tourist probably would not have visited Australia at all. On the other hand, if the delegate had no friends in Australia, the country might not have been as attractive as a destination, and the tourist might have decided not to attend the conference in the first place. Thus, there is interplay among the various travel purposes, and it is difficult to establish a meaningful ‘main’ purpose.Backer (2012) argues that 30there is a VFR component in 48 per cent of Australian domestic tourism if more broadly conceived, and by this same logic the ‘holiday’ percentage would be much higher again.

A further complication is that people in the same travel group may have different purposes for their trip. Our hypothetical conference delegate, for example, may be accompanied by a spouse who engages solely in pleasure/holiday activities. However, most surveys do not facilitate such multipurpose responses from different members of the same party. Rather, they assume that a single main purpose applies to all members of that group.

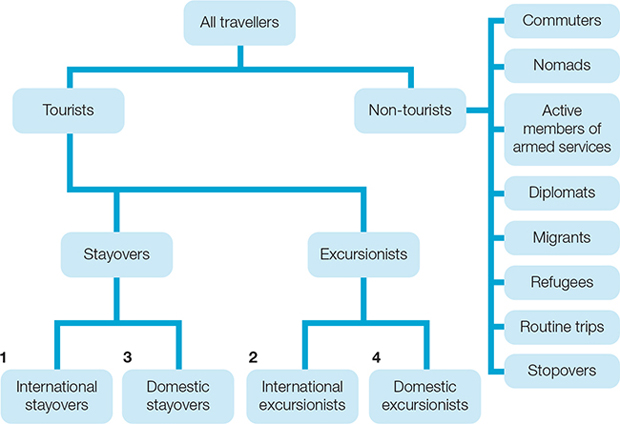

Major tourist categories

This chapter has earlier demonstrated that tourists can be either international or domestic, and also be either stayovers or excursionists. The combination of these spatial and temporal dimensions produces four major types of tourist (see figure 2.3) and these categories account for all tourist possibilities, assuming that the appropriate purposive criteria are also met.

International stayovers are tourists who remain in a destination outside their usual country of residence for at least one night (e.g. a Brisbane resident who spends a two-week adventure tour in New Zealand) but less than one year.

International excursionists stay in this destination without experiencing at least one overnight stay (e.g. a Brisbane resident on a cruise who spends six hours in Wellington).

Domestic stayovers stay for at least one night in a destination that is within their own usual country of residence, but outside of a ‘usual environment’ that is often defined by specific distance thresholds from the home site (e.g. a Brisbane resident who spends one week on holidays in Melbourne, travels to Perth for an overnight business trip or travels to the Gold Coast to spend a day at the beach).

Domestic excursionists undertake a similar trip, but without staying overnight (e.g. a Brisbane resident who flies to and from Melbourne on the same day to attend a rugby league match).

FIGURE 2.3 Four types of tourist within a broad travel context

31

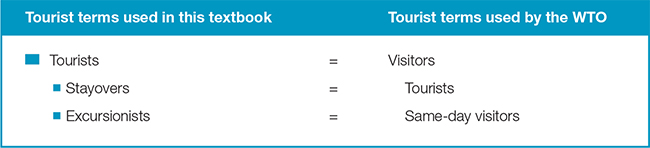

UNWTO terminology

The aforementioned tourist terms, while commonly used in the literature, do not match the terms that are used by the UNWTO. As indicated in figure 2.4, the UNWTO refers to all tourists as ‘visitors’ and reserves the word ‘tourist’ for the specific category of stayovers. In addition, those who are described as excursionists in this text are classified as ‘same-day visitors’ by the UNWTO. We reject this terminology as being counterintuitive. If interpreted literally, cruise ship excursionists and cross-border shoppers are excluded in any reference to the ‘tourist’. They fall instead under the visitor subcategory of ‘same-day visitor’. Nevertheless, students should be aware of the UNWTO terms, since they will be encountered in the many essential publications released by that organisation, and by governments and academics who adhere to their terminology.

FIGURE 2.4 Textbook and UNWTO tourist terminology

Stopovers

Stopovers are tourists or other travellers temporarily staying in a location while in transit to or from a destination region. The main criterion in international tourism that distinguishes a stopover from an inbound stayover or excursionist is that they normally do not clear customs or undergo any other border formalities that signify their ‘official’ presence in that location. To illustrate the point, a person travelling by air from Sydney to Toronto normally changes flights in San Francisco or Los Angeles. Most passengers disembark from the aeroplane in these transit nodes and wait in the transit lobby of the airport for three or four hours until it is time to board the aircraft for the second and final leg of this long-haul journey. These transit passengers are all stopovers. If, however, someone chooses to clear customs and spend a few hours shopping in the stopover city, they would be classified as an international excursionist or stayover to the United States, depending on whether an ‘overnight stay’ was included.

Changi Airport’s Butterfly Garden

The paradox is that most stopovers are indeed outbound tourists (unlike the other nontravelling categories), but are not classified as such from the perspective of the transit location. Several factors underlie this exclusion:

there is the previously mentioned fact that such travellers do not clear border formalities and hence are not official visitors

stopovers are not in the transit location by choice, although many may appreciate the opportunity to stretch their legs or make purchases

the economic impact of stopovers is usually negligible, with expenditures being restricted to the purchase of a few drinks, some food or a local newspaper.

32

Most stopover traffic occurs in the international airports of transportation hubs such as Singapore, Bangkok, Dubai and Frankfurt. In contrast, Australia’s location and size result in limited stopover traffic. Singapore, whose Changi Airport provides diverse services and attractions for stopovers including city tours (which converts them to excursionists and future stayovers), illustrates an innovative management approach toward deriving maximum economic benefit from transit passengers. These services and attractions also indicate blurring boundaries between transit and destination functions.

Data problems

Inbound tourist arrival statistics should be treated with caution, especially if they are being used to identify historical trends. This is in part because of the high margin of error that characterises older data in particular. For example, the UNWTO figure of 25 million international stayovers for 1950 (see table 3.1) is nothing more than a rough estimate, given that the data-collecting techniques of that era were primitive. At the scale of any individual country, this margin of error is amplified. More recent statistics have a smaller margin of error as a result of UNWTO initiatives to standardise definitions and data collection protocols. However, error still results from such things as inconsistencies from country to country in the collection and reporting of arrivals, expenditures and other tourism-related statistics. This is why UNWTO often adjusts country-level and aggregate arrival data from year to year and why only the statistics that are around five years old are stable.

Data-related problems are even more pronounced in domestic tourism statistics, largely because domestic tourist movements are difficult to monitor in most countries. Such statistics are often derived from the responses to surveys distributed at points of departure or solicited from a sample of households, from which broader national or state patterns are extrapolated. These surveys do not always employ appropriate survey design or sampling techniques (see chapter 12), though increasingly sophisticated computer-assisted techniques are being implemented by countries such as Australia and Canada that are committed to the effective development and management of their tourism industries. In Australia, compilation of the quarterly National Visitor Survey is facilitated by computer assisted telephone interviewing (CATI) systems that allow interviewers to read out by telephone the mostly multiple-choice questions that appear on the computer screen, efficiently key in responses which are then automatically coded into a database, and then rely on the computer to branch out to the next applicable question depending on what responses are given. The computer also assists with data verification and rescheduling uncompleted interviews, if required (TRA 2012a). At the subnational level, authorities sometimes still rely on extremely awkward and unreliable information sources such as sign-in books provided at welcome centres, visitor bureaus or attractions. Attempts to compare domestic tourism in different domestic jurisdictions are impeded by the proliferation of idiosyncratic definitions.

ORIGIN REGION

ORIGIN REGION

The origin region, as a component of the tourism system, has been neglected by researchers and managers. No tourism system could evolve but for the generation of demand within the origin region, and more tourism-related activity occurs there than is usually recognised. For discussion purposes, it is useful to distinguish between the origin community and the origin government.33

Origin community

Research into origin regions has concentrated on market segmentation and marketing (see chapters 6 and 7). Almost no attention, in contrast, has been paid to the impacts of tourism on the origin community even though there are numerous ways in which these impacts can occur. For example, some major origin cities can resemble ghost towns during long weekends or summer vacation periods, when a substantial number of residents travel to nearby beaches or mountains for recreational purposes. Local businesses may suffer as a result, while the broader local economy may be adversely affected over a longer period by the associated outflow of revenue. Conversely, local suppliers of travel-related goods and services, such as travel agencies, may thrive as a result of this tourist activity.

Significant effects can also be felt at the sociocultural level, wherein returning tourists are influenced by the fashions, food and music of various destinations. Such external cultural influences, of course, may be equally or more attributable to immigration and mass media, so the identification of tourism’s specific role in disseminating these influences needs to be clarified. Other tangible impacts include the unintended introduction of diseases (see Contemporary issue: Bringing more than good memories back to New Zealand). The formation of relationships between tourists and local residents also has potential consequences for origin communities. It is, for example, a common practice for male sex workers (i.e. ‘beach boys’) in Caribbean destinations such as the Dominican Republic to initiate romantic liaisons with inbound female tourists in the hope of migrating to a prosperous origin country like Canada or Italy (Herold, Garcia & DeMoya 2001). These examples demonstrate that at least some tourism management attention to origin regions is warranted, although another complicating variable is the extent to which the origin region also functions as a destination region, and is thus impacted by both returning and incoming tourists.

contemporary issue

![]() BRINGING MORE THAN GOOD MEMORIES BACK TO NEW ZEALAND

BRINGING MORE THAN GOOD MEMORIES BACK TO NEW ZEALAND

Between 1997 and 2009, 22 cases (20 confirmed and two probable) of Ross River fever (RRF), a debilitating mosquito-borne alphavirus, were reported in New Zealand. Twenty of these cases involved New Zealanders who had recently travelled to Australia or Fiji, where the virus is endemic. While no deaths and just three hospitalisations were associated with these cases, they illustrate the potential for outbound tourists to act as vectors for the introduction and spread of exotic infectious diseases in their origin countries (Lau, Weinstein & Slaney 2012). This is especially so since many cases are asymptomatic and therefore go unreported and untreated. Because there are no mosquito-borne diseases within New Zealand, it is also problematic that diagnostic efficiency there tends to be low. Moreover, projections of increased climate change could mean that the mosquito populations carrying RRF could become established in a warmer New Zealand, and that more returning New Zealanders will carry the virus home as those mosquito populations spread into other parts of Australia. Exacerbating the potential problem is the tendency of New Zealanders to engage in outdoor activities within Australia that maximise their exposure to mosquito hosts. Health alerts for outbound New Zealand tourists to 34affected countries are one way of reducing the risk of infection, so that appropriate measures such as the use of effective insect repellents and nets, and staying indoors during dawn and dusk, can be practised. New Zealand clinics and returning tourists also need to become more aware of RRF and its diagnostic characteristics, so that infected people can be more effectively identified and treated. RRF has the potential to become an emerging infectious disease in New Zealand, and returning outbound tourists are one of the most probable means through which this is likely to occur if sufficient precautions are not taken.

Origin government

The impacts of the origin government on the tourism system have also been largely ignored, in part because it is taken for granted in the more developed countries that citizens are free to travel wherever they wish (within reason). Yet this freedom is ultimately dependent on the willingness of origin national governments to tolerate a mobile citizenry. Even in democratic countries, some individuals have their passports seized to prevent them from travelling abroad. At a larger scale, prohibitions on the travel of US citizens to Cuba, imposed by successive US governments hostile to the regime of Fidel Castro, have effectively prevented the development of a major bilateral tourism system incorporating the two countries. In North Korea and other countries governed by totalitarian regimes, such restrictions are normal. An extremely important development in this regard has been the liberalisation of outbound tourist flows by the government of China, which in recent years has dramatically increased the number of countries with approved destination status (ADS) (Arita et al. 2011). Concurrently, the Chinese government exercises a high degree of control over domestic tourism, in particular through the designation of sanctioned holiday times (see Managing tourism: China’s Golden Weeks — golden for whom?).

managing tourism

![]() CHINA’S GOLDEN WEEKS — GOLDEN FOR WHOM?

CHINA’S GOLDEN WEEKS — GOLDEN FOR WHOM?

In China, the central government plays a powerful role in providing tightly structured holiday periods for its increasingly affluent population. This is especially evident in the two Golden Weeks established during the Chinese New Year and National Day periods to increase domestic tourism demand and stimulate consumption. The National Day Golden Week in 2009 generated 228 million tourists and 14.1 billion yuan in revenue (Pearce & Chen 2012), while the peak day of 3 October 2012 resulted in more than six million visitors to 119 centrally monitored scenic sites (Xinhua English News 2012). Many problems arise from such concentrated and intensive periods of travel — among them the transportation and accommodation systems within China being pushed far beyond their intended carrying capacity. The results have been described as a nightmare that far exceeds the worst experienced during Christmas holidays in the West. Survey results confirm that Chinese tourists cite excessive crowding and congestion as the biggest problem of the Golden Weeks, even while praising the long holiday period as a major social benefit (Pearce & Chen 2012). The Chinese government is aware of these problems and has been 35pressured by calls to cancel or reconfigure the holiday structure. One option is to encourage dispersal to more destinations, which would have the added benefit of stimulating regional development by distributing tourism employment and revenues more broadly. Others have called for more international travel, although nearby Hong Kong and Macau already experience an influx similar to that of the mainland. Regional countries such as Singapore, Malaysia and Thailand are starting to compete for a share of the market, citing their warm climates, accessibility and large Chinese minorities as attractions. As Golden Week participation continues to escalate, it may be expected that Western destinations such as Australia, New Zealand, the United States and the United Kingdom will join this competitive environment, emphasising their exotic appeal as high status destinations, encouraged by a strengthening Chinese currency and the greater ease of obtaining a visa.

In effect, the role of origin governments can be likened to a safety valve that ultimately determines the energy (i.e. tourist flow) that is allowed into the system (see chapter 3). Outbound flows are also influenced by the various services that origin governments offer to residents travelling or intending to travel abroad. In addition to consular services for citizens who have experienced trouble, these services largely involve advice to potential travellers about risk factors that are present in other countries. A good illustration is Australia’s Smartraveller website (www.smartraveller.gov.au) which, among other services, offers information about security risks for every foreign country.

TRANSIT REGION

TRANSIT REGION

As with origin regions, few studies have explicitly recognised the importance of the transit region component of the tourism system. This neglect is due in part to its status as a ‘non-discretionary’ space that the tourist must cross to reach the location that they really want to visit. Reinforcing this negative connotation is the sense, common among tourists, that time spent on the journey to a destination is holiday time wasted. Transit passages, moreover, are often uncomfortable, as economy-class passengers on a long-haul flight will attest. Under more positive circumstances, however, the transit region can itself be a destination of sorts as illustrated by the Changi airport example in Singapore. This illustrates what McKercher and Tang (2004) describe as stopover-focused ‘transit tourism’. This may also be the case, for example, if the journey involves a drive through spectacular scenery, or if the trip affords a level of comfort, novelty and/or activity that makes the transit experience comparable to that which is sought in a final destination.

As these examples illustrate, the distinction between transit and destination regions is not always clear (as in the use of the term ‘touring’), given that the tourist’s itinerary within a destination region will probably include multiple transit experiences (see figure 2.2). In many instances, a location can be important both as a transit and destination region. The Queensland city of Townsville, for instance, is an important transit stop on the road from Brisbane to Cairns, but it is also in itself an important emerging destination. The transit/destination distinction is even more ambiguous in cruise ship tourism, where the actual cruise is a major component of the travel experience and a ‘destination’ in its own right.

Management implications of transit regions

Once the status of a place as a transit node or region is determined, specific management implications become more apparent, such as the need to identify associated impacts. For airports, this frequently involves increased congestion from stopovers 36that impedes the arrival and departure of stayovers. In highway transit situations, a major impact is the development of extensive motel (motor hotel) strips along primary roads on the outskirts of even relatively small urban centres. A related management consideration is the extent to which the transit region can and wishes to evolve as a destination in its own right, a scenario that can be assisted by the presence of accommodation or airports.

Managers of destination regions also need to take into consideration the transit component of tourism systems when managing their own tourism sectors. Pertinent issues include whether the destination is accessible through multiple or single transit routes and which modes of transportation provide access. Destinations that are accessible by only one route and mode (e.g. an isolated island served by a single airport and a single airline) are disadvantaged by being dependent on a single tourism ‘lifeline’. However, this may be offset by the advantage of having all processing of visitors consolidated at a single location. A further consideration is the extent to which a transit link is fixed (as with a highway) and can be disrupted if associated infrastructure, such as a bridge, is put out of commission by a road accident or natural disaster. In contrast to road-based travel, air journeys do not depend on infrastructure during the actual flight, and have greater scope for rerouting if a troublesome situation is encountered (e.g. a war breaking out in a fly-over country or adverse weather conditions).

Destination managers also need to consider the possibility that one or more locations along a transit route could become destinations themselves, and thus serve as intervening opportunities that divert visitors from the original destination. Cuba, for example, is currently little more than an incidental transit location in the United States-to-Jamaica tourism system due to the above-mentioned hostility of the US government towards the Castro regime. However, if a major change in US foreign policy led to the re-opening of Cuba to US mass tourism, then the impact upon the Jamaican tourism sector could be devastating.

Effects of technology

Technological change has dramatically affected the character of transit regions. Faster aircraft and cars have reduced the amount of time required in the transit phase, thereby increasing the size of transit regions by making long-haul travel more feasible and comfortable. New aircraft models such as the Airbus A380 and the Boeing 787 Dreamliner promise to radically reshape the transit experience for travellers as well as airports, although their introduction has not been problem-free. Not all major airports have strong or long enough runways, or properly configured gates, to accommodate the giant Airbus A380. The option of lounges and extra personal space in all classes, moreover, means that fuel savings from increased efficiency may be largely offset by lower passenger capacity. Electrical and fuel leak problems, meanwhile, have plagued the introduction of the Dreamliner (Mail Online 2013).

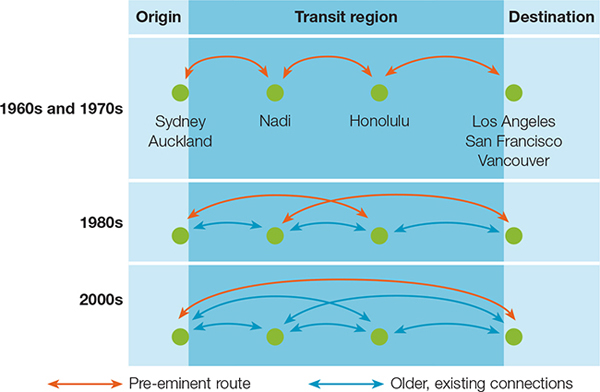

Such aircraft also no longer require as many refuelling stops on long-haul flights, resulting in further reconfigurations to transit hubs and regions. Figure 2.5 shows that a flight from Sydney or Auckland to a North American port of entry prior to the 1980s required transit stops in Fiji (Nadi airport) and Hawaii (Honolulu). By the 1980s only one stopover landing was required — Hawaii on the flight to North America and Fiji on the return journey. By the mid-1990s such flights could be undertaken without any stopovers. The overall effect has been the marginalisation of many former stopover points, a process that in some cases has had negative implications for their development as final destinations.37

A similar marginalisation effect has resulted from the construction of limited access expressways in countries such as the United States, Canada and Australia. By diverting traffic from the old main highways, these expressways have forced the closure of many roadside motels that depended on travellers in transit. In the place of the traditional motel strip, clusters of large motels, usually dominated by major chains (such as Holiday Inn, Motel 6 and Comfort Inn) have emerged at strategic intersections readily accessible to the expressway. These clusters contribute to suburban sprawl by attracting affiliated services such as petrol stations and fast-food outlets.

FIGURE 2.5 The evolution of the trans-Pacific travel system

In broad terms, the latter half of the twentieth century was the era in which the car and the aeroplane became pre-eminent, at the expense of the passenger ship and the passenger train (see chapter 3). Places that relied on the ship and the train, accordingly, have declined in importance as transit and destination regions (e.g. train stations and some ports), if they were unwilling or unable to compensate by developing their road or air access, or by catering to niche nostalgia-motivated markets. Contemporary concerns about climate change, however, may lead to renewed interest in ships and trains as transit carriers due to their lower greenhouse gas emissions (Becken & Hay 2012).

DESTINATION REGION

DESTINATION REGION

The destination region is the geographical component of the tourism system that has received by far the greatest scrutiny from researchers, planners and managers. During the era of the advocacy platform, this attention focused on the destination-based tourism industry. Researchers were at that time concerned largely with determining how the industry could effectively attract and satisfy a profit-generating clientele. During the period of the cautionary and adaptancy platforms, the research emphasis shifted towards the identification of host community impacts and strategies for ensuring that these were more positive than negative. More of a balance between industry and community is apparent in the present knowledge-based platform, based on a growing realisation that the interests of the two components are not mutually exclusive.

38The distribution of destination regions changed dramatically during the latter half of the twentieth century, and is constantly being reconfigured, vertically as well as horizontally, through technological change and consumer interest. In the vertical reconfiguration, space tourism is now a reality since the American multimillionaire Dennis Tito went into space aboard a Russian Soyuz capsule in 2001 as a tourist (Reddy, Nica & Wilkes 2012). Relatively large numbers of space tourists have already signed up for or taken much less expensive ‘parabolic flights’ in which zero-gravity conditions are maintained briefly prior to descent (see Technology and tourism: Rocketing into space? Not so fast!). At the other end of the vertical spectrum, several underwater hotels have been proposed, though none had yet been constructed as of 2013.

technology and tourism

![]() ROCKETING INTO SPACE? NOT SO FAST …

ROCKETING INTO SPACE? NOT SO FAST …

Technology often expands beyond the ability of humans to cope effectively with the impacts of its expansion, and this ‘reality check’ is currently being faced in the burgeoning field of space tourism. With the European Space Agency declaring ‘cautious interest and informed support’ for space tourism, and commercial opportunities becoming more viable, as many as 13 000 seats could become available once commercial space vehicles are operational. According to Grenon et al. (2012), tourists who take advantage of suborbital flights and other space tourism experiences face potential medical problems. For those with existing conditions, there are concerns about appropriate parameters of participation; for example, for someone with a recent knee replacement, how long should they wait before going on such a trip, and what should be the maximum time spent in a suborbital environment? Is there an optimal minimum and maximum age? The experience of astronauts and cosmonauts is not especially helpful since their screening ensures participation of only the extremely healthy and fit. Even for potential space travellers with no serious medical conditions, clinical research has revealed that such travel poses higher risks of kidney stones, heart arrhythmias, osteoporosis and muscle atrophy upon the return to earth, and even of some kinds of cancer due to increased exposure to radiation and immunosuppression (Grenon et al. 2012). Space tourists would also be vulnerable to other impacts common to air travel — for example, motion sickness, appetite loss, fatigue, insomnia, dehydration and back pain. This indicates the importance of risk management for providers as well as potential customers and healthcare practitioners. Likely outcomes include the disqualification of individuals with high-risk conditions, but also the development of medical technologies to lower these risks. A new organisation, the Center of Excellence for Commercial Space Transportation, is developing ‘medical acceptance guidelines’ for spaceflight participants (COE CST 2012). The ongoing articulation of such standards will be an important facilitator of future commercial and consumer entry into space tourism, thereby lowering the risks of litigation for all parties.

Change in the configuration of destination regions is the result of internal factors such as active promotional efforts and decisions to upgrade infrastructure, but also external factors associated with the broader tourism system and external environments. An example is the emergence of consumer demand for 3S (i.e. sea, sand, sun) tourism after World War II, which led to the large-scale tourism development of hitherto isolated tropical islands in the Caribbean, South Pacific and Indian Ocean (see chapter 4). Concurrently, the opening of these islands to mass tourism could not 39have taken place without radical developments in aircraft technology. One implication of this external dependency, and of systems theory in general, is that destinations can effectively manage and control only a very small proportion of the forces and variables that affect their tourism sectors. Even effectively managed destinations and businesses can be severely impacted by the negative intervention of forces over which they have no control (see the case study at the end of this chapter).

Destination communities

Even under the advocacy platform, destination residents were recognised as an important component of the tourism system because of the labour they provide, and in some situations because of their status as cultural tourism attractions in their own right. However, only in rare situations when that platform was dominant was the destination community recognised as an influential stakeholder in its own right, on par with industry or government. The increasing recognition of host communities as such has arisen from greater awareness of at least three factors:

local residents usually have the most to lose or gain from tourism of any stakeholder group in the tourism system, and therefore have a strong ethical right to be empowered as decision makers

discontented local residents through their hostility to tourists can damage the tourism industry by fostering a negative destination image (see chapter 9)

local residents possess knowledge about their area that can assist the planning, management and marketing of tourism, as through interpretation of local historical and cultural attractions and the preparation of unique local foods.

For all these reasons, host communities are now often included as equal partners (at least in rhetoric) in the management of tourist destinations, and not seen as just a convenient source of labour or local colour, or a group whose interests are already represented by government.

Destination governments

If origin governments can be compared with a safety valve that releases energy into the tourism system, then the destination government can be likened to a safety valve that controls the amount of energy absorbed by the destination components of that system. This analogy is especially relevant at the international level, where national governments dictate the conditions under which inbound tourists are allowed entry (see chapter 4). To a greater or lesser extent, countries exert control over the number and type of tourist arrivals by requiring visas or passports from potential visitors, and by restricting the locations through which access to the country can be gained. Most countries, in principle and practice, encourage tourist arrivals because of the foreign exchange that they generate. Even Bhutan and North Korea, which traditionally discouraged inbound tourism, are becoming more receptive to the industry despite long-held respective concerns about the cultural and political risks of international tourism exposure.

In addition to this entry control function, destination governments also explicitly influence the development and management of their tourism products through support for tourism-related agencies. These include tourism ministries (either tourism by itself or as part of a multisectoral portfolio) that are concerned with overall policy and direction, and tourism boards, which focus on destination marketing. More unusual are agencies that focus on research, such as Tourism Research Australia. Many high-profile tourist destinations, such as the United States and Germany, have no federal high-level portfolio emphasising tourism. This reflects to some extent the residual negative perceptions of 40tourism discussed in chapter 1, but also political systems that devolve responsibilities such as tourism to the state level. Thus, while tourism promotion in the US at the federal level is negligible, states such as Florida and Hawaii operate enormous tourism marketing entities. In Australia, well articulated federal structures are complemented by similarly sophisticated state bodies such as Tourism Queensland and Tourism Victoria.

THE TOURISM INDUSTRY

THE TOURISM INDUSTRY

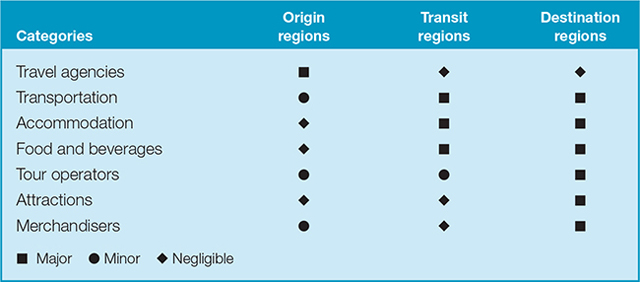

The tourism industry (or tourism industries) may be defined as the sum of the industrial and commercial activities that produce goods and services wholly or mainly for tourist consumption. Broad categories commonly associated with the tourism industry include accommodation, transportation, food and beverage, tour operations, travel agencies, commercial attractions and merchandising of souvenirs, duty-free products and other goods purchased mainly by tourists. These activities are discussed in chapter 5, but several preliminary observations are in order. First, the tourism industry permeates the tourism system more than any other component aside from the tourists themselves. However, as depicted in figure 2.6, segments of the industry vary considerably in their distribution within the three geographic components of tourism system. Not all spatial components of the system, moreover, accommodate an equal share of the industry. Destination regions account for most of the tourism industry, whereas origin regions are represented in significant terms only by travel agencies and some aspects of transportation and merchandising. The inclusion of industry into tourism management considerations is therefore particularly imperative at the destination level.

FIGURE 2.6 Status of major tourism industry sectors within the tourism system

A confounding element in the above definition of the tourism industry is the extent to which various commercial goods and services are affiliated with tourism. At one extreme almost all activity associated with travel agencies and tour operators is tourism-related. Far more ambiguous is the transportation industry, much of which involves the movement of goods (some related to tourism) or commuters, migrants and other travellers who are not tourists. It proves especially difficult to isolate the tourism component in automobile-related transportation. Similar problems face the accommodation sector despite its clearer link to tourism, since many local residents purchase space at nearby hotels for wedding receptions, meetings and other functions. It is largely because of these complications that no Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) code is likely to be allocated to tourism (see figure 1.2).

41

CHAPTER REVIEW

The complexities of tourism can be organised for analytical and management purposes through a systems perspective. A basic whole systems approach to tourism incorporates several interdependent components, including origin, transit and destination regions, the tourists themselves and the tourism industry. This system, in turn, is influenced by and influences various physical, political, social and other external environments. The challenge of managing a destination is compounded by this complexity. The tourist component of the system is defined by spatial, temporal and purposive parameters, and these lead to the identification of four major tourist types: international and domestic stayovers, and international and domestic excursionists. Recreation and leisure are the single most important purposes for tourism travel, followed more or less equally by visits to friends and relatives, and business. There are also many qualifying minor purposes including education, sport, health and pilgrimage. Despite such definitional clarifications, serious problems are still encountered when defining tourists and collecting tourist-related data, especially at the domestic level. In terms of the geography of tourism systems, origin and transit regions are vital, but neglected, components of the tourism system in terms of the research that has been conducted. Much greater attention has been focused on the destination region and the tourism industry. Important preliminary observations with regard to the latter include its concentration within the destination region, and the difficulty in isolating the tourism component in many related industries such as transportation.

SUMMARY OF KEY TERMS

SUMMARY OF KEY TERMS

Basic whole tourism system an application of a systems approach to tourism, wherein tourism is seen as consisting of three geographical components (origin, transit and destination regions), tourists and a tourism industry, embedded within a modifying external environment that includes parallel political, social, physical and other systems

Destination community the residents of the destination region

Destination government the government of the destination region

Destination region the places to which the tourist is travelling

Domestic excursionists tourists who stay within their own country for less than one night

Domestic stayovers tourists who stay within their own country for at least one night

Domestic tourist a tourist whose itinerary is confined to their usual country of residence

Excursionist a tourist who spends less than one night in a destination region

Golden Weeks two one-week periods of annual holiday in China, focused around Chinese New Year and National Day, and characterised by extremely intensive domestic travel

Inbound tourists international tourists arriving from another country

International excursionists tourists who stay less than one night in another country

International stayovers tourists who stay at least one night in another country

International tourist a tourist who travels beyond their usual country of residence

Intervening opportunities places, often within transit regions, that develop as tourist destinations in their own right and subsequently have the potential to divert tourists from previously patronised destinations42

Long-haul tourists variably defined as tourists taking trips outside of the world region where they reside, or beyond a given number of flying time hours

Medical tourism travel for the purpose of obtaining medical treatment that is unavailable or too expensive in the participant’s region of origin

MICE an acronym combining meetings, incentives, conventions and exhibitions; a form of tourism largely associated with business purposes

Multipurpose travel travel undertaken for more than a single purpose

Origin community the residents of the origin region

Origin government the government of the origin region

Origin region the region (e.g. country, state, city) from which the tourist originates, also referred to as the market or generating region

Outbound tourists international tourists departing from their usual country of residence

Resilience a system’s capacity to maintain and adjust its essential structure and functions in the face of a disturbance, especially with regard to major natural and human-induced disasters; its particular relevance to tourism derives from the industry’s presence in vulnerable settings such as coastlines and mountains

Secular pilgrimage travel for spiritual purposes that are not linked to conventional religions

Short-haul tourists variably defined as tourists taking trips within the world region where they reside, or within a given number of flying time hours

Space tourism an emerging form of tourism that involves travel by and confinement within aircraft or spacecraft to high altitude locations where suborbital effects such as zero-gravity or earth curvature viewing can be experienced

Stayover a tourist who spends at least one night in a destination region

Stopovers travellers who stop in a location in transit to another destination; they normally do not clear customs and are not considered tourists from the transit location’s perspective

System a group of interrelated, interdependent and interacting elements that together form a single functional structure

Tourism industry the sum of the industrial and commercial activities that produce goods and services wholly or mainly for tourist consumption

Transit region the places and regions that tourists pass through as they travel from origin to destination region

Travel purpose the reason why people travel; in tourism, these involve recreation and leisure, visits to friends and relatives (VFR), business, and less dominant purposes such as study, sport, religion and health

VFR tourism tourism based on visits to friends and relatives

QUESTIONS

QUESTIONS

Why and how in practical terms is a systems approach useful in managing the tourism sector?

How does this approach complement the knowledge-based platform?

What are the main external natural and cultural environments that interact with the tourism system?

What can destination managers do to minimise the negative impacts of these systems?

How could the breaking of the one billion threshold for international stayovers be leveraged by the global tourism industry to increase public and government awareness?

43Why are domestic tourists relatively neglected by researchers and government in comparison to international tourists?

What can be done to reverse this neglect?

To what extent are the three main travel purposes discretionary in nature?

What implications does this have for the management and marketing of a destination?

How are origin regions influenced by returning outbound tourists?

How can origin regions reduce the negative impacts of returning outbound tourists?

Why is it important for destination managers to have a good understanding of the transit regions that convey tourists to their businesses and attractions?

What would be a realistic assessment of the potential market for a space tourism experience in the year 2020?

EXERCISES

EXERCISES

Write a 1000-word report in which you:

describe the extent to which Singapore functions simultaneously as an origin region, transit region and destination region, and

discuss the potential synergies and conflicts that emerge from each of the three region combinations (e.g. origin/transit, origin/destination, transit/destination).

Have each class member define their most recent experience as a tourist, in terms of which of the four categories in figure 2.3 it falls under, and also which purpose or purposes as outlined in ‘Travel purpose’ section.

Describe the overall patterns that emerge from this exercise.

Identify any difficulties that emerged in defining each of these tourist experiences.

FURTHER READING

FURTHER READING

Connell, J. 2013. ‘Contemporary Medical Tourism: Conceptualisation, Culture and Commodification’. Tourism Management 34: 1–13. An overview of medical tourism is provided, including issues of definition, motivations and magnitude.

Dowling, R. (Ed.) 2006. Cruise Ship Tourism. Wallingford, UK: CABI. This compilation of 38 chapters provides the most thorough academic investigation of the cruise ship industry to date, with sections devoted to demand and marketing, destinations and products, industry issues, and impacts.

Duval, D. 2007. Tourism and Transport: Modes, Networks and Flows. Clevedon, UK: Channel View. Duval’s book provides an extensive and useful examination of the transportation and transit components of tourism systems.

Raj, R. & Morpeth, N. (Eds) 2007. Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage Festivals Management. Wallingford, UK: CABI. International case studies representing major world religions are featured in this compilation, which considers the management implications and issues associated with pilgrimages and other forms of religion-based tourism.

44Reddy, M., Nica, M. & Wilkes, K. 2012. ‘Space Tourism: Research Recommendations for the Future of the Industry and Perspectives of Potential Participants’. Tourism Management 33: 1093–102. This is the first paper to reflect on the overall structure, frameworks and issues associated with the emergent area of space tourism, and to propose a research agenda.

case study

![]() POST-TSUNAMI ENTERPRISE RESILIENCE IN PHUKET, THAILAND

POST-TSUNAMI ENTERPRISE RESILIENCE IN PHUKET, THAILAND

Tourism systems at the destination scale can be severely damaged by unexpected natural or human-induced disasters. Hence, as tourism spreads to ever more places where such incidences are more common, resilience to their impacts will be an increasingly important consideration in destination planning and management. Originating in the ecological sciences, the concept of resilience can be defined as ‘the ability of a system to maintain and adapt its essential structure and function in the face of disturbance while maintaining its identity’ (Biggs, Hall & Stoeckl 2012, p. 646). Very few researchers have attempted to analyse tourism systems within a resilience framework, perhaps because of the exceptional complexity that arises from the interaction of numerous natural and social systems.