Destination development

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

discuss the relevance and implications of the destination cycle concept for tourism managers

outline the destination cycle as described in the Butler sequence

explain how different elements of the tourism experience — such as the multiplier effect, stages of commodification and psychographic segmentation — can be incorporated into the destination cycle

critique the strengths and limitations of the Butler sequence, and of the destination cycle concept in general, as a device to assist destination managers

categorise the factors that contribute to changes in the destination cycle, and assess the extent to which destination managers can influence these factors

explain how tourism development at a national scale can be described as a combined process of contagious and hierarchical spatial diffusion

describe how the destination cycle concept can be accommodated within the pattern of tourism development that occurs at the national scale.

286

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

The previous two chapters considered the economic, sociocultural and environmental costs and benefits that are potentially associated with tourism, primarily from a destination perspective. All tourism activity induces change within a destination, and this usually involves a combination of both costs and benefits for all stakeholders. Whether the net impacts are positive or negative for the destination overall or for particular stakeholders depends on a variety of factors, including the destination’s level of economic development and diversity, its sociocultural and physical carrying capacity, and, critically, the amount, rate and type of tourism development relative to these internal factors. This chapter examines the process of destination development in more detail, by integrating the content of earlier chapters on impacts, markets, destinations and tourism products. The following section considers the concept of the destination cycle, and focuses specifically on the Butler sequence, which is the most frequently cited manifestation. This section also provides a critique of the model, and examines the factors that can contribute to changes in the destination cycle. The dynamics of tourism development at a national scale, which are usually not adequately described by the cycle concept as represented by the Butler sequence, are then considered. The concept of spatial diffusion is presented as an alternative model that more accurately describes the evolution of tourism at a national scale.

DESTINATION CYCLE

DESTINATION CYCLE

The idea that destinations experience a predictable evolution is embodied in the concept of the destination cycle. This theory, to the extent that it is demonstrated to have widespread relevance to the real world, is of great interest to tourism managers, who would then know where a particular destination is positioned within the cycle at a given point in time and what implications this has for the future if no intervention is undertaken. The destination cycle, this latter clause suggests, should not be regarded as an unavoidable process, but rather one that can be redirected through appropriate management measures to realise the ecologically and socioculturally sustainable outcomes that are desired by destination stakeholders (see chapter 11).

Allusions to the idea of a destination cycle were made in the early tourism literature, as illustrated in the following 1963 quotation by Walter Christaller, a famous geographer:

The typical course of development has the following pattern. Painters search out untouched unusual places to paint. Step by step the place develops as a so-called artist colony. Soon a cluster of poets follows, kindred to the painters; then cinema people, gourmets, and the jeunesse dorée. The place becomes fashionable and the entrepreneur takes note. The fisherman’s cottage, the shelter-huts become converted into boarding houses and hotels come on the scene. Meanwhile the painters have fled and sought out another periphery … More and more townsmen choose this place, now en vogue and advertised in the newspapers. Subsequently, the gourmets, and all those who seek real recreation, stay away. At last the tourist agencies come with their package rate travelling parties; now, the indulged public avoids such places. At the same time, in other places the same cycle occurs again; more and more places come into fashion, change their type, turn into everybody’s tourist haunt (Christaller 1963, p. 103).

During the 1970s, early theorists in resident attitudes, commodification and psychographics also implied the existence of a destination cycle, though their research 287focused only on specific aspects of that progression rather than the macro-process (see chapter 9). Resident attitudes, for example, were assumed to progress from euphoric to antagonistic as tourism progressively overwhelmed the destination. Concurrently, it was believed that a shift from allocentric to psychocentric tourists occurred. None of these theorists, however, integrated these ideas into a larger tourism systems framework.

The Butler sequence

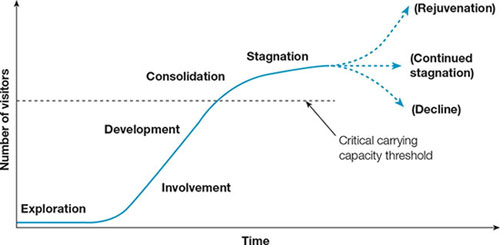

Influenced by this earlier research, Butler in 1980 presented his S-shaped resort cycle model, or Butler sequence, which proposes that tourist destinations tend to experience five distinct stages of growth (i.e. exploration, involvement, development, consolidation, stagnation) under free market and sustained demand conditions (Butler 1980). Depending on the response of destination managers to the onset of stagnation, various scenarios are then possible, including continued stagnation, decline and/or rejuvenation (see figure 10.1). Although usually not stated in applications of the model, the Butler sequence assumes a sufficient level of demand to fuel its progression, as per the ‘push’ factors outlined in chapter 3.

Before describing the stages in more detail, it is important to stress that the Butler sequence has become one of the most cited and applied models within the field of tourism studies. Its longstanding appeal is based on several factors, some of which merit mention here, and others that will be elaborated on in the critique that follows the presentation of the stages.

First, the model is structurally simple, being based on a concept — the product lifecycle curve — that has long been used by economists and marketers to describe the behaviour of the market in purchasing consumer goods such as televisions and cars. The reader will also note its superficial similarity to the pattern of population growth depicted in the demographic transition model (see figure 3.5). Its simplicity and prior applications to areas such as marketing and demography make Butler’s resort cycle curve accessible and attractive, as well as readily applicable using available data such as visitor arrivals or a surrogate such as accommodation units.288

Second, Butler’s model has intuitive appeal, in that anyone who has travelled extensively or who has conducted tourism research will agree that some kind of cyclical dynamic is indeed evident in most destinations.

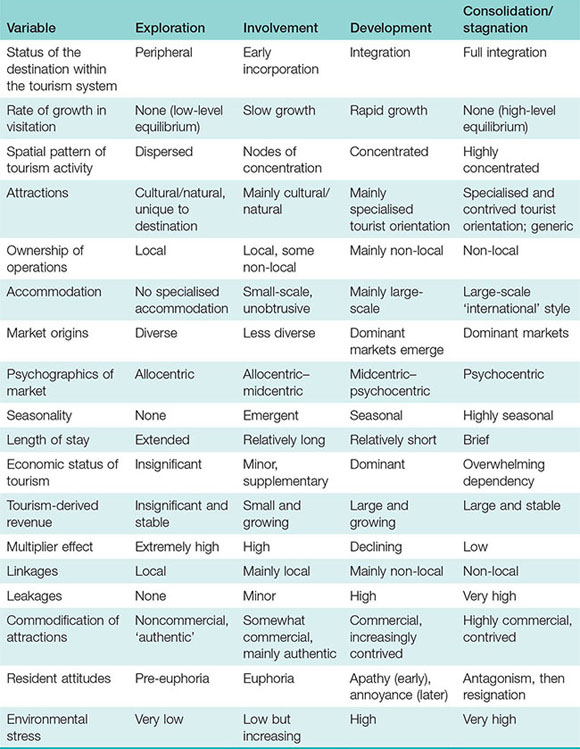

Third, the Butler sequence is a comprehensive, integrated model that allows for the simultaneous incorporation of all facets of tourism in a destination beyond the visitor numbers that are used to construct the curve. Table 10.1 summarises the more important of these facets in terms of their relationship to the first five stages of the model and forms the basis for the following discussion of the individual stages. Finally, it appears to be universally applicable, in that there is nothing inherent in its structure that restricts its relevance to only certain types of destination or environment, at least at a localised scale.

TABLE 10.1 Changing characteristics as proposed by the Butler sequence

289

Exploration

According to Butler, the exploration stage is characterised by very small numbers of visitors who are dispersed throughout the destination and remain for an extended period of time. The tourism ‘industry’ as such does not exist, as the negligible visitor numbers do not merit the establishment of any specialised facilities or services. The tourists themselves are adventurous, allocentric types who are drawn by what they perceive to be authentic and ‘unspoiled’ pre-commodified cultural and natural attractions. These visitors arrive from a wide variety of sources and are not influenced significantly by seasonality. Although the absolute revenue obtained from the tourists in the exploration stage is very small, linkages with the local economy are extensive because of their desire to consume interesting local products, and hence the multiplier effect is large. For this reason, and because the locals maintain control, the relationship with tourists is mostly cordial, and the tourists tend to be treated either as curiosities or honoured guests. These attitudes may be described as pre-euphoric, in that tourism is not yet making a large enough impact to substantially benefit the economy of the destination.

In essence, exploration is a kind of informal ‘pre-tourism’ stage where visitors must accommodate themselves to the services and facilities that already exist in the area to serve local residents. For example, tourists have to shop in the local market and travel by the local bus system. From a systems perspective, the exploration-stage destination is only peripherally and informally connected to any origin or transit regions.

On a worldwide scale, the number of places that display exploration-type dynamics is rapidly diminishing due to the explosive growth of tourism since 1950. The remaining exploration-stage places largely coincide first with wilderness or semi-wilderness areas where any kind of formal economic activity is absent, rudimentary or focused on some specialised primary activity such as mining or forestry. Most of the Australian interior and northern coast, aside from urban areas and certain high-profile national parks, is in the exploration stage. A similar logic applies to many locations within northern Canada, the Amazon Basin, Siberia and central Asia, Antarctica, Greenland and the Congo River Basin in Africa. Residual exploration-stage locations also include settled areas that lack tourism activity due to conditions of war or civil unrest (e.g. Afghanistan), inaccessibility imposed internally or externally (e.g. North Korea and Iraq before the US invasion, respectively) or a general combined lack of significant pull effects (e.g. large parts of rural China and India). A complicating factor is that exploration-type dynamics might apply to one group of tourists in a particular destination but not to others (see Managing tourism: Two-track tourism in Iraq?).

managing tourism

![]() TWO-TRACK TOURISM IN IRAQ?

TWO-TRACK TOURISM IN IRAQ?

A tourist poses with Iraqi-provided security

War and tourism share an unusual relationship in which the former has the initial effect of destroying the latter, but then stimulates longer term tourism development through the establishment of dark tourism attractions, and markets (returning combatants and their families) drawn to those attractions years later. The small but growing leisure tourism sector in Iraq was destroyed by the invasion of United States and allied troops in 2003. Although the ‘victorious’ allies withdrew in late 2011, Iraq has remained a place of persistent sectarian conflict and instability that is not conducive to the renewal of leisure tourism for Western travellers. Nevertheless, there is ample evidence of exploration-type activity that may pave the way for redevelopment. Several 290 adventure tour companies, for example, are offering tours to iconic sites such as the ruins of Babylon and other sites of the ancient civilisations of the Fertile Crescent (an arc-shaped region where agriculture is thought to have been first practised). Kurdish-controlled areas in the north-east in particular are considered to be the most stable in the country. One tour operator claimed in 2009 that participants had very positive impressions of Iraq, which they communicated through social media and word-of-mouth recommendations, paving the way for other allocentrics (Rivera 2009). For its part, Iraq attended the World Travel Market Exhibition in London for the first time in 2009; however, it continues to face reluctant foreign investors and continued insecurity (Riviera 2009). As a result, less than 200 Western tourists visited Iraq in 2012, with the tourism minister citing a ‘complicated’ situation of decaying infrastructure and the need to have armed guards posted at attractions and accompanying tour groups (Dreazen 2012). Because credit cards are not yet accepted, tourists are common targets for criminals because they need to carry large amounts of cash. Such concerns, however, have not dissuaded the more than one million Shi’ite pilgrim tourists from Iran and elsewhere who visited Iraq in 2012, triggering a hotel construction boom in the holy cities of Najaf and Karbala (Dreazen 2012). Could it be that two parallel destination cycles are in play in Iraq?

Involvement

Several developments characterise Butler’s involvement stage.

Local entrepreneurs begin to provide a limited amount of specialised services and facilities in response to the regular appearance of tourists, thereby inaugurating an incipient and, at first, largely informal tourism industry. These services and facilities typically consist of small guesthouses and inns, and eating places; and include the provision of guides, small tour operations and a few small semi-commercial attractions. Often, residents simply make one or two rooms within their houses available for a nominal fee.

This incipient and still largely informal tourism sector begins to show signs of concentration within local settlements, transportation gateways or near tourist attractions. However, the sector is still small-scale, and has little visual or environmental impact on the landscape.

The visitor intake begins to increase slowly in response to these local initiatives, ending the low-level equilibrium of visitor arrivals that characterised the exploration stage.

Because tangible economic benefits are increasing and control is local, the involvement stage is associated with strongly positive community attitudes toward tourism. However, the growing intake is already mediated to some extent by the formal tourism system, thereby opening the way for non-local participation and for greater numbers of midcentric tourists. For example, while some backpackers and academics might still arrive by walking or by four-wheel drive or relatively primitive local transport, others of a less adventurous persuasion begin to arrive by mini-vans provided by tour operators in a nearby city or by small aeroplane. These developments indicate that the area is gradually becoming more integrated into the tourism system, with formal businesses becoming more involved because of the increased tourist demand. Concurrently, 291residents begin to consciously or subconsciously demarcate backstage and frontstage spaces and times to cope with the growing number of visitors, and are more conscious of the possibilities for commodification.

Factors that trigger the involvement stage

The factors that trigger the transition from exploration to involvement can be either internal or external. Internal forces are those that arise from within the destination community itself, such as the adventurous entrepreneur who builds and advertises a new kind of attraction as a way of inducing increased visitation levels. External forces originating from outside the destination can be small-scale and cumulative, as in word-of-mouth marketing by previous visitors within their origin regions. Each visitor, for example, might relate their adventures in the ‘untouched’ destination to ten other people, some of whom are subsequently inspired to visit the destination. The ubiquitous use of social media accelerates this process. The result in either case is an increase in tourism numbers.

Conversely, the external factor can be a high-profile event, such as the publication of a National Geographic magazine article, a television documentary, the visit of a celebrity or exposure in a popular movie (Connell 2012). The construction of a major airport or road is another possible trigger. In these instances, specific events serve as catalysts for dramatic and almost immediate increases in visitation. All of the examples given, of course, can also occur at later stages, though in those instances the tourism sector and the cycle dynamics are already well established (see the ‘Factors that change the destination cycle’ section).

The importance of understanding the trigger factors is demonstrated by the effect that these can have on the subsequent dynamics of the destination cycle. Internal forces imply that the destination, or a stakeholder within the destination, is taking a proactive approach towards tourism development, which increases the likelihood that local control will be retained and the community will be better equipped to adjust to increases in visitation, perhaps through a deliberately prolonged involvement stage. In contrast, external forces of the singular, large-scale variety tend to induce rapid change that is directed by outside interests — the community has the immediate disadvantage of being placed on the defensive, having to react to events rather than direct them. Under these circumstances, the involvement stage is likely to be little more than a brief prelude to the development stage.

In Australia the involvement stage seems to describe the many rural Indigenous Australian communities which are making tentative attempts to pursue tourism as a means of bringing about effective economic development. In such cases, the employment of a proactive approach to the trigger factors is essential given the cultural and economic circumstances of those communities. The issue is also imperative in non-Indigenous Australian rural areas and settlements which, while faced with different circumstances and issues, are also increasingly entering the involvement stage in their own quest for a viable local economy.

Development

The development stage is characterised by rapid tourism growth and dramatic changes over a relatively short period of time in all aspects of the tourism sector. As with all other phases of the Butler sequence, the change from involvement to development is usually marked by a transition rather than a sharp boundary, although specific events (e.g. construction of the first mega-resort or a celebrity visit) can act as a catalyst for accelerated change. The rate and character of the growth will depend on 292the pull factors (see chapter 4) that prevail during the stage, and the attempts made in the destination to manage the process. In the Butler sequence, a rapid erosion in the level of local control is assumed to occur as the community is overwhelmed by the scale of tourism development. As the destination is rapidly integrated into the formal tourism system, larger non-local and transnational companies gain control over the process, attracting midcentric and psychocentric consumers who arrange and facilitate their travel experiences (often through package tours) within these highly organised structures.

Spatially, the development stage is a time of rapid landscape change, as small hotels and guest houses give way to large multi-storey resorts; agricultural land is replaced by golf courses, second-home developments and theme parks; and mangroves are removed to make way for marinas. Large areas of farmland may be abandoned after being purchased by speculators, or because labour and investment have been diverted to tourism. The ‘sense of place’ or uniqueness of the destination that was associated with the exploration and involvement stages gives way to a generic, ‘international’-style landscape. Concentrated tourism districts form along coastlines, in alpine valleys or in any other area that is close to associated attractions or gateways. At this point environmental stresses are widespread, and negative environmental responses are apparent. The general attitude of residents towards visitors also experiences a rapid transformation. In the early development stage, tourists become a normal part of the local routine, prompting widespread apathy. However, as tourist numbers continue to mount, and as resultant pressures are placed on local carrying capacities, apathy may give way to annoyance within a growing portion of the population. Typically, aspects of the destination’s culture become highly commodified.

Australian destinations that appear to be in the development stage include Queensland’s Sunshine Coast, Hervey Bay and Cairns; New South Wales coastal resorts such as Port Macquarie, Coffs Harbour and Byron Bay; and the Western Australian resort town of Broome. Noncoastal destinations that also appear to qualify include alpine resorts such as Thredbo, and tourist shopping villages such as Maleny, Mount Tamborine and Hahndorf in the respective hinterlands of the Sunshine Coast, the Gold Coast and Adelaide.

Consolidation

The consolidation stage involves a decline in the growth rate of visitor arrivals and other tourism-related activity, although the total amount of activity continues to increase. Visitor numbers over a 12-month period are usually well in excess of the resident population. Of paramount importance in this stage is the visible breeching of the destination’s environmental, social and economic carrying capacities, thereby indicating increased deterioration of the tourism product and the subsequent quality of the tourist and resident experience.

During consolidation, crowded, high-density tourism districts emerge and are dominated by a psychocentric clientele who rely largely on short-stay package tour arrangements affiliated with large tour operators and hotel chains. The destination is wholly integrated into the large-scale, globalised tourism system, and tourism dominates the economy of the area. Attractions are largely specialised recreational sites of a contrived, generic nature (symbolised by theme parks, golf courses and casinos). Seasonality emerges as a major influence on the destination’s economy, along with high turnover in hotel and restaurant ownership, and abandonment of facilities and areas due to a lack of interest in redevelopment. Much of this is due to transnational companies that ‘abandon’ the destination to seek the greener pastures elsewhere.293

It is in the consolidation stage that the local social ‘breaking’ point is likely to be reached, with some residents becoming blatantly antagonistic towards tourists, while others become resigned to the situation and either adjust to the new environment or leave the area altogether. Some residents will blame tourism for all problems, justifiably or not. As negative encounters with the local residents and local tourism product increase, word-of-mouth exchange of information between tourists and acquaintances contributes to the reduced visitor intakes.

Destinations that appear to have experienced consolidation-like processes at some point in their development include the Surfers Paradise district of the Gold Coast (perhaps the best Australian example) as well as other pleasure periphery tourism cities along the French and Spanish Rivieras, in Florida and the Bahamas, and in the Waikiki area of Honolulu.

Stagnation

Peak visitor numbers and levels of associated facilities, such as available accommodation units, are attained during the stagnation stage. Surplus capacity is a persistent problem, prompting frequent price discounts that lead to further product deterioration and bankruptcies, given the high fixed costs involved in the sector. One way that companies respond to this dilemma is to convert hotel-type accommodation into self-catering apartments, timeshare units or even permanent residences for retirees, students or others. The affected destination may still have a high profile, but this does not translate into increases in visitation due to the fact that the location is perceived to be ‘out of fashion’ or otherwise less desirable as a destination. Indicative of stagnation, aside from the stability in the visitor intake curve, is the reliance on repeat visits by psychocentrically oriented visitors — the moribund destination is now less capable of attracting new visitors due to pervasive negative coverage by the media, or through word-of-mouth or social media communication. It may also be that many repeat visitors are spuriously loyal.

Stagnation-type dynamics have been identified in parts of the Riviera, such as Spain’s Costa Brava, and in some areas of Florida and the Caribbean (e.g. the Bahamas’ New Providence Island). Beyond the global pleasure periphery, it is discernible in the recreational hinterlands that have developed within a one-day drive of large north American cities, including Muskoka (Toronto), the Laurentians (Montreal) and the Catskills (New York City). The rural nature of these regions, however, suggests different structural characteristics than those associated with urban areas.

Decline or rejuvenation

The stagnation stage can theoretically persist for an indefinite period, but it is likely that the destination will eventually experience either an upturn or a downturn in its fortunes.

Decline

The scenario of decline, beyond destructive external factors such as war or natural disasters, will occur as a result of some combination of the following tourism-related factors.

Repeat clients are no longer satisfied with the available product, while efforts to recruit new visitors fail.

The major attractions that a destination depends upon are no longer available due to immediate events (e.g. a fire or closure) or longer-term disruptions (see Breakthrough tourism: Come and see it before it’s gone …).294

No attempts are made by destination stakeholders to revitalise or reinvent the local tourism product, or these attempts are made but are unsuccessful.

Resident antagonism progresses to the level of outright and widespread hostility, which contributes to the negative image of the destination.

New competitors, and particularly intervening opportunities, emerge to divert and capture traditional markets.

As tourist numbers decline, more hotels and other specialised tourism facilities are abandoned or converted into apartments, health care centres or other uses suitable for retirees. Ironically, this may have the effect of allowing locals to re-enter the tourism industry, since outmoded facilities can be obtained at a relatively low price. Similarly, the decline of tourism often reduces that sector’s dominance of the destination as other service industries (e.g. health care, call centres, government) are attracted to the area in response to its changing demographics. The decline stage may be accelerated by a ‘snowballing’ effect, wherein the abandonment of a major hotel or attraction impacts negatively on the viability of other accommodation or attractions, thereby increasing the possibility of their own demise.

The number of destinations that have at some point experienced significant decline-stage dynamics — that is, more than one or two years of decline — is not large. The Coolangatta district of the Gold Coast is probably the best Australian example (Russell & Faulkner 2004), while one of the most illustrative international cases is Atlantic City from the post–World War I period to the 1960s. Other historical examples include Cape May (New Jersey) whose pre-eminence as a summer seaside resort for Philadelphia ironically was destroyed in the late 1800s by the emergence of Atlantic City. Additional examples can be found within the older established areas of southern Florida (e.g. Miami Beach in the 1970s), the French and Spanish Rivieras and Hawaii.

breakthrough tourism

![]() COME AND SEE IT BEFORE IT’S GONE …

COME AND SEE IT BEFORE IT’S GONE …

Destination cycle deliberations tend to ignore the possibility of a final termination of tourism, but such scenarios are now being seriously considered in some places because of the anticipated local effects of climate change. Perversely, this has attracted the interest of some consumers who want to visit these endangered places before they disappear. The activity that has emerged as a result of such interest is known as last chance tourism (Lemelin, Dawson & Stewart 2011). One example of this form of tourism occurs in Churchill, Manitoba (Canada), where a majority of interviewed tourists in one survey agreed that they were motivated to visit Churchill in order to see polar bears — by far the most popular town attraction — before global warming destroyed their natural habitat. It was less obvious to them that their own travel to Churchill was a contributing factor to this climate change (Dawson et al. 2010).

Other ethical issues that should be considered in relation to last chance tourism include the more traditional carrying capacity threats that result from significant increases in the number of these tourists, and the voyeuristic quality of such travel, which seems to have affiliations with dark tourism and ego-enhancement. Is it therefore ethical for some tour operators and 295destinations to make a profit from such activity, even if there are only subtle signs that these attractions are disappearing? Assuming that such travel cannot be prevented, it would be constructive to see how last chance tourism could be mobilised as a positive force by providing climate change focused product interpretation and education for visitors. They might then become advocates and ambassadors for relevant environmental causes, although there is as yet no empirical evidence for this laudable outcome. Operators could also be encouraged to donate a portion of their profits to climate change mitigation or constructive adaptation of the threatened product (e.g. relocating polar bears).

Rejuvenation

The other alternative is a rejuvenation of the destination’s tourism industry. While the Butler sequence shows this occurring after the stagnation stage, it is also possible that rejuvenation will take place following a period of decline, with decreasing numbers serving as a catalyst for action. Weaver (2012) subsequently argues that the stagnation and especially the decline stage serve as catalysts for the creation of an ‘arena of innovation’ in which destination stakeholders are compelled to exhibit their latent capacity for responding creatively and effectively to major internal and external challenges. This was the case with Atlantic City’s decision to introduce legalised casino-based gambling, breaking the monopoly held by Las Vegas (Stansfield 2006). According to Butler, rejuvenation is almost always accompanied by the introduction of entirely new tourism products, or at least the radical reimaging of the existing product, as a way of recapturing the destination’s competitive advantage and sense of uniqueness. Instances of reliance on new products also include Miami Beach, which restructured the existing 3S product in the 1980s to capitalise on the city’s remarkable art deco hotel architecture to attract the nostalgia market. A similar scenario of nostalgia-based reimaging is feasible for Coolangatta and older summer resorts on the Atlantic coast and Great Lakes shoreline of North America. Miami’s rejuvenation was assisted in the mid-1990s by a crackdown on crime, which did much to change the city’s image as a dangerous destination. Finally, Douglass and Raento (2004) describe how the gambling haven of Las Vegas has periodically reinvented itself, shifting from its shady image in the 1980s to a ‘family friendly’ destination, and then more recently to an edgier product exemplified by the advertising slogan ‘What happens in Vegas stays in Vegas’. Major efforts to improve the physical environment and quality of life are also typical of rejuvenation initiatives (see Contemporary issue: Resilience and adaptability in a mature destination).

contemporary issue

![]() RESILIENCE AND ADAPTABILITY IN A MATURE DESTINATION

RESILIENCE AND ADAPTABILITY IN A MATURE DESTINATION

FIGURE 10.2 Benidorm: A nice place to visit and reside

The experience of Benidorm, on Spain’s Costa Blanca, demonstrates how long-term decline can be averted in mature 3S tourism cities (Ivars, Rodríguez & Vera 2013). With 68 000 accommodation beds and over 10 million visitors in 2010, it maintains high occupancy rates through most of the year and a high average length of stay. Benidorm remains a very popular destination for UK visitors in particular. Creative and proactive local responses to various global developments have given rise to at least four phases of ‘maturity’ since the late 1980s rather 296than the expected period of prolonged decline. Between 1988 and 1993, recession occurred due to the appreciation of the Spanish currency, conflict in the Middle East, and a global economic downturn. New attractions, restorations and a training centre limited the resultant decline in visitation, paving the way for an expansion period from 1994 to 2001 when the local currency was devalued and economic recovery occurred in source countries. To stimulate visitation, local leaders upgraded existing hotels and opened new urban landmarks and public spaces, thereby reinforcing product quality, diversity and a sense of place. During the 2002–07 stabilisation stage, visitation was stagnant due to the emergence of competing destinations and low-cost carriers, as well as the Iraq war. One local response was additional 4- and 5-star construction, and further development of business and wellbeing products to diversify the tourist market (Claver-Cortés, Molina-Azorin & Pereira-Moliner 2007). Visitation again declined during the global economic crisis of 2007–09, although it was neither severe nor lasted long. One enduring factor in the resilience of Benidorm was the early decision to favour a high urban density model leading to greater efficiency in the use of water, energy and land as well as less dependency on private transport. Close cooperation between the public and private sectors, and emphasis on both the inbound and domestic markets have also assisted in averting a classic decline dynamic (see figure 10.2).

The implication of these examples is that rejuvenation seldom occurs as a spontaneous process, but arises from deliberate, proactive strategies adopted by destination managers and entrepreneurs. Success in achieving revitalisation is associated with the ability of the public and private sectors, with collaboration from the community, to cooperate in focusing on what each does best. The public sector provides destination marketing, suitable services and the management of public attractions, and the private sector assumes a lead role in industry sectors such as accommodation, food and beverages, tour operations, transportation and some categories of attraction.

Application and critique of the Butler sequence

The examples used in the preceding discussion illustrate the broad potential applicability and intuitive appeal of the Butler sequence as a model to describe the development of tourist destinations, wherein negative economic, sociocultural and environmental impacts increase and accumulate as the destination moves through the development stage. A major implication of the model is the idea that tourism carries within itself the seeds of its own destruction, and that proactive management strategies are essential, as early as possible or through the arena of innovation later in the cycle, if this self-destruction is to be avoided.

Cycle applications

Since its publication in 1980, the Butler sequence has been empirically examined well over 50 times just within the published English-language literature. The great majority of these applications have identified a general conformity to the broad contours of the model, supporting its potential as an important theoretical as well as practical device for describing and predicting the evolution of destinations. However, most 297applications have also identified one or more anomalies where the sequence does not apply to the targeted case study, and/or where the overall results of the exercise remain ambiguous (see Table 10.2). For example, in Grand Cayman Island and Melanesia, it was found that the earliest tourism initiatives in these colonial situations were carried out by external interests associated with the colonial power, and that local, non-elite participation increased as tourism became more developed. Serious resident annoyance and antagonism in the Solomon Islands also occurred when this destination was barely into the involvement stage, due in part to low resilience to change within the local community.

TABLE 10.2 Selected anomalies to the Butler sequence in empirical case studies

| Case study | Anomaly |

| Grand Cayman Island (Caribbean) (Weaver 1990) Melanesia (Douglas 1997) |

Involvement began with external rather than local initiative |

| Niagara Falls (Canada) (Getz 1992) Prince Edward Island (Canada) (Baum 1998) Torbay (United Kingdom) (Agarwal 1997) |

Local control retained well beyond the involvement stage |

| Coolangatta (suburb of Gold Coast, Australia) (Russell & Faulkner 2004) | Involvement stage bypassed altogether (i.e. the suburb transitioned from the exploration to development stage) |

| Thredbo (Australia) (Digance 1997) | High seasonality in early stages moved toward low seasonality |

| Niagara Falls (Canada) (Getz 1992) | Contrived specialised recreational attractions did not replace original natural attraction (waterfall) |

| Israeli seaside resorts (Cohen-Hattab & Shoval 2005) | Stagnation stage induced by government, not private sector |

| St Andrews (Scotland) (Butler 2011) Eastern Townships of Quebec (Canada) (Lundgren 2006) |

Sequence of cycles occurred over time |

In the case of Niagara Falls, there was no evidence for the loss of local control until well into the late development stage, nor was there evidence that the clientele was shifting towards a psychocentric mode. Furthermore, specialised recreational attractions, such as theme parks, did not supersede the iconic waterfall as the destination’s primary draw. In the English seaside resort of Torbay, local control was retained during the development stage and beyond. In addition, visitors did not display any behaviour during these later stages suggestive of psychocentrism. The involvement stage in Coolangatta (on the southern Gold Coast) was effectively bypassed by the rapid onset of mass tourism, and the dynamics of the consolidation stage were far more complex and multifaceted than proposed by Butler. (Butler himself recognised that the involvement stage could be pre-empted by the ‘instant resort’ effect created by Cancún-like growth pole strategies.) In the case of some Israeli seaside resorts, the government — rather than the private sector — was identified as the main agent contributing to stagnation.

Although the Canadian province of Prince Edward Island experienced stagnation in the early 1990s on the basis of visitation levels, the destination retained a structure of small-scale and local ownership typical of the involvement stage. With regard to 298seasonality, the Australian ski resort of Thredbo evolved from an essentially winter-only resort to a year-round destination, thus reversing the expected seasonality pattern. In the Eastern Townships region of Quebec (Canada), at least three tourism cycles were identified over a 200-year period, each focused on a different regional tourism product. Similarly, the Scottish resort of St Andrews experienced successive cycles based on a sequence of new product introductions, giving rise to a stepped pattern of growth. An unusual application of the sequence is provided by Whitfield (2009), who found that the convention sector in the United Kingdom displays different stages of the cycle, depending on whether the venues were purpose-built, hotels, educational establishments or visitor attractions.

General criticisms

Clearly, then, many deviations have been identified when the Butler sequence has been subjected to empirical testing. At a more general level, the sequence can be criticised for its determinism — that is, the implication that a destination’s progression through a particular sequence of stages is inevitable. In reality, there is no inherent reason to assume that all exploration- or involvement-stage destinations are fated to pass beyond these initial phases. Such a progression may be highly probable in a small fishing village opened up by a new highway along a scenic coastline, but much less so in an isolated agricultural settlement in New South Wales or northern China. Tourism planners and managers should therefore make the effort to identify and then focus on those early stage destinations that are likely to experience further development, rather than worrying that every such destination will face this problem.

Determinism is also evident in the assumption that the cyclical dynamics of tourist destinations begin with the appearance of presumably Western explorer-tourists in the exploration stage. Weaver (2010) argues that indigenous communities experience a distinctive tourism cycle in which traditional indigenous people themselves participate as tourists in a ‘pre-exploration’ stage that precedes the Western exploration phase. Notably, only a few empirical studies on the sequence have been undertaken in Asia despite the potential of that rapidly growing tourism region to serve as a laboratory for destination cycle dynamics in a non-Western context (see the case study at the end of this chapter).

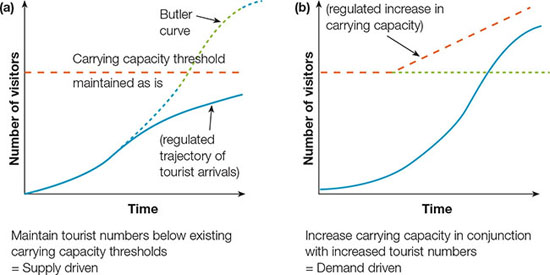

This issue of determinism extends to the proposed carrying capacity thresholds (see figure 10.1). According to the Butler sequence, tourism development escalates until these thresholds are exceeded; however, managers and communities, as emphasised earlier, can and often do override free market forces and take proactive measures to ensure that tourism does not impact negatively on the destination. As depicted in figure 10.3, there are two basic ways in which this can be achieved.

Supply-driven scenario

In supply-driven scenario (a), the carrying capacities are deliberately left as they are, but the level of development is curtailed so that they remain below the relevant thresholds. Essentially, a long involvement stage of slow growth is induced, followed by consolidation at a desired level, with ‘development’ being avoided altogether. This could be achieved through a number of strategies, alone or in combination, including:

placing restrictions or quotas on the allowable number of visitors (as in Bhutan before the early 2000s)

imposing development standards

introducing limitations to the size and number of accommodation facilities

zoning only certain limited areas for frontstage tourism development

299

FIGURE 10.3 Alternative responses to the Butler sequence

prohibiting the expansion of infrastructure, such as airports, that would facilitate additional tourism development

increasing entry fees to the destination (e.g. visa fees) in order to reduce demand.

Many of these strategies relate to the tactics of obtaining supply–demand equilibrium as outlined in chapter 7, although the emphasis there was mainly in the private sector, at a microscale, and related to corporate profitability rather than destination-wide impacts. It should be noted here, however, that such public sector strategies may be resisted by a local tourism industry that sees this as an erosion of its customer base and profitability.

Demand-driven scenario

In demand-driven scenario (b), the conventional sequence of involvement and development takes place, but measures are taken to raise carrying capacity thresholds in concert with the increased visitor intake. This can be achieved on the sociocultural front by demarcating and enforcing frontstage/backstage distinctions (see chapter 9) or by introducing tourist and resident education and awareness programs (see chapter 7). On the environmental front, destinations can make pre-emptive human responses to environmental stresses, including site-hardening initiatives such as the installation of improved sewage and water treatment facilities. Economic adjustments might include the expansion of local manufacturing and agricultural capacities in order to supply the required backward linkages to the tourism sector (see chapter 8). In effect, scenario (b) involves the increase of supply to meet demand, while scenario (a) involves the suppression of demand to fit the existing supply. The issue of proactive responses to the ‘classic’ Butler sequence in order to achieve more sustainable outcomes is pursued further in chapter 11.

The question of geographic scale

As discussed in earlier chapters, the term ‘destination’ can be applied at different scales, ranging from a single small attraction to an entire continent (e.g. Asia or Europe) or macroregion (e.g. the pleasure periphery). This raises the question as to whether certain scales are more suited to the application of the Butler sequence than others. Because visitation levels and surrogates such as the number of accommodation units 300can be graphed at any scale, there has been a tendency in the literature to assume that the Butler sequence can be applied across the geographical spectrum.

The resemblance to Butler’s curve, however, is often superficial. This is because the dynamics discussed by Butler cannot be meaningfully applied at the country level due to great internal diversity, unless the country happens to be a particularly small entity (e.g. a SISOD). The problem can be illustrated by considering Spain, where national visitation levels indicate the later development or very early consolidation stage. However, it is absurd to imagine that all or most of Spain’s 40 million residents are now expressing antagonism towards tourists, or that all of its tourist accommodation is now accounted for by large, ‘international’-style hotels. Such circumstances may apply to parts of the Spanish Riviera, but not to most parts of inland rural Spain, which is mostly at the involvement or early development stage. Similarly, overall inbound arrival statistics for Australia disguise great disparities between the exploration-stage Outback and poststagnation dynamics that are evident in parts of the Gold Coast. In essence, Butler’s cycle, in its classic format, does not apply to such large countries because of the tendency of large-scale tourism to concentrate only in certain areas of these countries (see chapter 4). More productive, as discussed in the final section, are attempts to model the diffusion of tourism, and hence the differential progression of the resort cycle, within large areas.

The Butler sequence itself, as demonstrated by the array of case studies in table 10.2, is more appropriately applied at the scale of a well-defined individual resort concentration such as the Gold Coast, Byron Bay, Spain’s Costa Brava, a small Caribbean island such as Antigua, or an alpine resort such as Thredbo or St Moritz (Switzerland). However, caution must still be exercised since significant internal variations often occur even at this scale. This is illustrated by the Gold Coast, where the apparent stagnation stage of Surfers Paradise contrasts with the appearance of exploration-type dynamics in many parts of the hinterland and in numerous residential suburbs that accommodate no leisure tourism activity at all. Even within a single theme park, it is likely that some long-established thrill rides demonstrate characteristics of stagnation and decline, while a new ride displays development-type growth due to its novelty factor.

Cross-sectoral considerations

A related concern is the influence on destination development of sectors external to tourism. Applications of the resort cycle model often give the impression that tourism is the only economic activity carried out in the destination, so that resident reactions and environmental change are influenced only by this one sector. This isolationist approach ignores the external environment that must be taken into consideration in the analysis of tourism systems (see chapter 2). In reality, few (if any) destinations are wholly reliant on the tourism industry. In the case of Las Vegas, the city is also extremely important as a wholesale distribution point, centre for military activity and health care, and a magnet for high-tech industry. Australia’s Gold Coast and Sunshine Coast are also not predominantly reliant on tourism. The question of tourism growth leading to the breaching of carrying capacity thresholds must therefore take into account the moderating (or exacerbating) influences of these coexisting activities. The problem can also be illustrated by a large nonresort city such as London or Paris. Such centres have a very large tourism industry that appears to be in the consolidation stage, but this sector accounts for only a small portion of the city’s total economic output. Hence, it is not rational to assume that the onset of tourism consolidation in Paris or London will result in widespread antagonism, or a complete dependency on tourism.301

Tourism dynamics are additionally affected by non-economic external factors such as political unrest and natural disasters, which also need to be taken into account in the management of destination development. The dramatic decline in visitation induced by the 2004 tsunami in Phuket (Thailand) is one notable Asian example. Within Australia, the Queensland city of Bundaberg experienced successive disastrous floods in 2011 and 2013 which both times resulted in dramatic visitation declines due to damaged infrastructure and negative media publicity (Stafford 2013). Possible links with climate change suggest that such extreme weather events may become more frequent, making this perhaps the greatest challenge for resilience in vulnerable destinations. A more directly ‘man-made’ example is the Varosha neighbourhood of Famagusta, Cyprus, a formerly vibrant high-rise resort district which became a ghost town after the Turkish invasion of Cyprus in 1974, and still remains in this condition.

The Butler sequence as an ‘ideal type’

The Butler sequence, in summary, best describes destinations that are:

relatively small

spatially well defined

highly focused on tourism

dominated by free market (or ‘laissez-faire’) forces

in high demand.

Its applicability to real-life situations, therefore, seems to be limited, and apparently out of all proportion to the considerable attention that it has received in the tourism literature. Yet, the attention paid to the Butler sequence is justified because of the model’s utility as an ideal type against which real-life situations can be measured and compared. The Butler model (as with any model), in essence, shows what takes place when the distortions of real life are removed — it is a deliberately idealised situation that functions as a benchmark.

With this ‘pure’ structure as a frame of reference, the researcher can see how much a real-life case study situation deviates from that model, and then try to identify why this deviation occurs. For example, it was noted that local control actually increased with accelerated tourism development on Grand Cayman Island, a situation that can be attributed to the status of this island as a colony where British and Jamaican interests had the capital and inclination to initiate the involvement stage while most locals were focused on working in the fisheries or other maritime industries. In the case of Niagara Falls, the presence of an overwhelmingly dominant and iconic natural attraction appears to have prevented a situation where contrived, specialised recreational attractions become more important than the original primary cultural or natural attractions. The implication, which can be illustrated with many more examples, is that different types of circumstances result in different types of deviations from the model. Continued identification and testing for such deviations may allow distinctive variants of the cycle to be identified, resulting eventually in a constellation of subsets that take these real-life circumstances into account.

FACTORS THAT CHANGE THE DESTINATION CYCLE

FACTORS THAT CHANGE THE DESTINATION CYCLE

The trigger factors that induce a transition from the exploration stage to the involvement stage have been considered. These and other factors also influence change in later stages of the cycle, whether the latter conforms to the Butler sequence or not. Managers benefit from a better understanding of these ongoing influences, in particular, 302because the destination in the post-involvement stages can experience not only further growth, but also decline. This understanding includes an awareness of the degree to which various factors can be controlled and manipulated. Clearly, it is desirable that the managers of a destination should retain control or at least influence over as many of these as possible, so that they can shape a desirable evolutionary path for the destination.

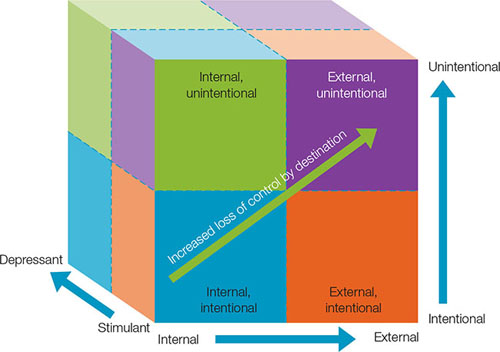

The factors that influence the evolution of tourism in destinations can be positioned within a simple eight-cell matrix model of cycle trigger factors (see figure 10.4). As with the attraction inventory discussed in chapter 5, the dotted lines indicate that each variable can be measured along a continuum — discrete categories are used as a matter of convenience for discussion purposes, rather than as an indication that all factors neatly fit into eight homogeneous cells.

FIGURE 10.4 Matrix model for classifying cycle trigger factors

Internal-intentional actions

From a destination perspective, the ‘ideal’ situation involves stimulants that originate deliberately from within the destination, or internal-intentional actions. Applicable stimulants that trigger further growth include infrastructure upgrading, environmental improvements, effective marketing campaigns directed by the local tourism organisation, innovative investments in facilitating technologies by local risk-taking entrepreneurs (see Technology and tourism: Technology cycles), and the decision by local authorities to pursue a growth pole-type strategy based on tourism. Conversely, internal and intentional depressants, such as entry fees and infrastructure restrictions, can be used deliberately to restrict or reverse the growth of tourism. Not all these factors, however, are instigated or desired by destination managers, as illustrated by home-grown terrorist groups in countries such as Egypt that attempt to sabotage the country’s tourism industry. A fully legal decision by other stakeholders to build a nuclear reactor could be similarly dissuasive to tourism.303

technology and tourism

![]() TECHNOLOGY CYCLES

TECHNOLOGY CYCLES

A QR code used to advertise an art exhibition

Any discussion of social media or other technologies as facilitators or inhibitors of destination development should bear in mind that these are also subject to cyclical dynamics. The research and development stage, accordingly, is analogous to ‘exploration’ and ‘involvement’, while ascent (when costs have been recovered and possession of the product is normative) is similar to ‘development’. Maturity is analogous to the destination cycle’s ‘consolidation’ and ‘stagnation’ stages and decline (or decay) occurs when the technology becomes obsolete or replaced by a superior or more attractive alternative. As with destinations, not all technologies pass through the entire cycle, and many innovations are aborted in the research and development stage or do not survive initial market trials. In some cases, as with ‘rejuvenation’ in a destination, incremental innovations may be sufficient to revitalise an existing product. For destination planners and managers, there are significant implications. Late adoption of a specific traffic management system or computer software package, for example, might result in the waste of considerable money if the system is about to be superseded by a better product. In such cases, financial and organisational lock-in effects might result in the inefficient and obsolete system being retained. An organisation that retains a particular smartphone platform for reasons of cost and habit, and does not convert to one better suited to their purposes, may illustrate this phenomenon. Conversely, early adoption of QR (quick response) codes — a technology that allows marketers to link smartphone users to their websites via optically scanned coded labels — may stimulate tourist attraction visitation by technologically savvy tourists who might otherwise be too time-poor to manually search online for information. In studying destination dynamics, it would be useful to compare the cycle stage of the destination with the stages of vital technologies that affect it, bearing in mind that the product lifecycle duration of technology is often much shorter than destination cycles. Rational decisions could then be made about investing in products that are most conducive to positive destination development.

External-unintentional actions

Trigger factors that originate from beyond the destination, and in an unintentional way, can be described as external-unintentional actions. Because they are spatially removed in origin from the destination, and because they are not the deliberate result of certain actions, they tend to be highly unpredictable both in character and in outcome, and mostly uncontrollable by destination managers. They are therefore the least desirable outcome from a destination perspective, and furthermore, indicate how much developments within the destination are vulnerable to uncertain, external forces. Examples of external-unintentional depressants include cyclones that periodically disrupt the tourism industry in northern Queensland or Vanuatu, climate change and its harmful impact on the Great Barrier Reef, and political chaos in Indonesia in so far as it hinders tourism in Bali. Ironically, many of these same factors are external-unintentional tourism stimulants for other destinations. For example, political instability in Indonesia 304has had the effect of diverting many Australian tourists to Thailand and Malaysia, or to long-haul regions such as Europe.

Internal-unintentional actions

Internal-unintentional actions, as with external-intentional actions, are intermediate between the first two categories with respect to the control that can be exercised by the destination. Examples of internal-unintentional depressants include a prolonged civil war (though some civil wars can also be intentional) or coral reef destruction caused by a local pollution source. Originating within the jurisdiction of the destination, managers and other authorities are in a better position to deal with these situations in comparison to those associated with outside forces, although the latter will no doubt have some influence over internal developments.

External-intentional actions

The opposite situation is described by external-intentional actions. Depressants in this category include a country that drastically and dramatically devalues its currency, perhaps in part to become a more affordable and attractive destination competitor relative to an adjacent country. The legalisation of gambling in Atlantic City was a potential depressant for Las Vegas, but in retrospect could be considered a stimulant because of its role in forcing Las Vegas to rejuvenate its product. A less ambiguous example of a stimulating effect is the opening of a new transportation corridor, such as a railway, within a transit region, to expedite the movement of tourists from an origin to a destination region. Movies and television shows that feature locations are also potential external-intentional stimulants.

NATIONAL TOURISM DEVELOPMENT

NATIONAL TOURISM DEVELOPMENT

As argued, the Butler sequence, and the destination cycle concept in general, are not applicable at the scale of entire countries, except for those that are exceptionally small. To gain insight into the process of tourism development at the country scale, it is helpful to revisit the internal spatial patterns described in chapter 4, which involve the concentration of tourism within large urban centres and in built-up areas adjacent to attractions such as beaches and mountains. To understand how these patterns have emerged and are likely to evolve in the future, and thereby help to understand when and how cyclical dynamics occur at the local destination level, an understanding of the concept of spatial diffusion is essential.

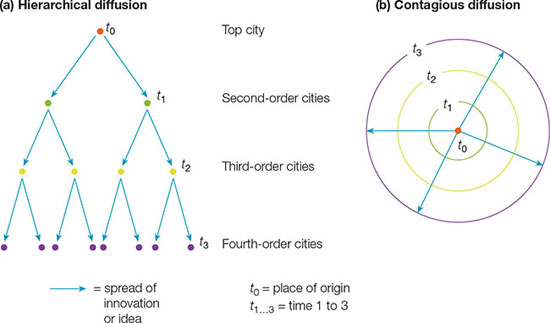

Spatial diffusion

Spatial or geographical diffusion is the process whereby an innovation or idea spreads from a point of origin to other locations (Getis et al. 2011). Spatial diffusion can be either contagious or hierarchical. In hierarchical diffusion, the idea or innovation typically originates in the largest urban centre, and gradually spreads through communications and transportation systems to smaller centres within the urban hierarchy. This process is modelled in part (a) of figure 10.5. To illustrate, television stations in the United States first became established in large metropolitan areas such as New York and Chicago in the late 1940s, and soon thereafter started to open in second-order cities such as Boston and Denver. Within five years, they were established in small regional cities of about 100 000 population and in many cities of 50 000 or fewer by 1960. 305The larger the city, the higher the probability therefore of early adoption. Less frequently, diffusion can occur in the opposite direction, as illustrated by the movement of musical forms such as the blues and country from rural areas of origin to large urban centres.

FIGURE 10.5 Hierarchical and contagious spatial diffusion

In contagious diffusion, the spread occurs as a function of spatial proximity. This is demonstrated by the likelihood that a contagious disease carried by a student in a classroom will spread first to the students sitting next to the infected student, and lastly to those sitting farthest away. Contagious diffusion is sometimes likened to the ripple effect made when a pebble is thrown into a body of still water. A good historical example is the expansion of Islam from its origins around the cities of Mecca and Medina to the remainder of the Arabian Peninsula, and then rapidly into the rest of the Middle East, Central Asia and North Africa.

In both modes of diffusion, the ideal depictions in figure 10.5 are distorted by real-life situations, as with the Butler sequence. It is useful in the diffusion discourse, therefore, to identify barriers that delay or accelerate the process, and that channel the process in specific directions. The contagious diffusion of Islam, for example, was halted in Ethiopia by effective resistance from Christians in their mountain strongholds. The discussion will now focus on the combined application of these spatial diffusion concepts to national-scale tourism development.

Effects of hierarchical diffusion

The concentration of tourism activity in urban areas is a manifestation of hierarchical diffusion. A country’s largest city (e.g. Paris, Sydney, Toronto, New York, Nairobi and Auckland) is likely to function as the primary gateway for inbound tourists. Also, because of its prominence, it will contain sites and events of interest to tourists (e.g. opera house, parliament buildings, museums and so on). The dominant city, then, is often the first location in a country to host international tourism activity on a formal basis. For the same reasons, this centre also acts as a magnet for domestic visitors.

As the urban hierarchy of the country evolves, the same effect occurs on a reduced scale as the smaller cities (e.g. state capitals, regional centres) begin to provide more 306and better services and attractions in their own right. Thus, tourism spreads over time into lower levels of the urban system, a process that is assisted by improvements in the transportation networks that integrate the urban hierarchy — in essence, the tourism system expands by ‘piggybacking’ on the expansion of external systems such as transportation. However, tourism itself may contribute in some measure to this expansion of the urban hierarchy, in so far as it acts as a propulsive activity for spontaneous (e.g. Gold Coast) or planned (e.g. Cancún) urban development in coastal areas or other regions where tourist attractions are available.

Effects of contagious diffusion

The effects of contagious diffusion follow on from the effects of hierarchical diffusion. As cities grow, they emerge as significant domestic tourism markets in their own right as well as increasingly important destinations for inbound tourists. Both markets stimulate the development of recreational hinterlands around these cities, the size of which is usually proportional to the population of the urban area. As the city grows, the recreational hinterland expands accordingly. Tourist shopping villages in the urban–rural fringe of the Gold and Sunshine coasts, such as Tamborine Mountain and Maleny respectively, are examples of this phenomenon at the excursionist level, while Muskoka (in the Canadian province of Ontario) and the Catskills (in the American state of New York) illustrate stayover-oriented recreational hinterlands on a larger spatial scale.

Once a community becomes tourism oriented (i.e. ‘adopts’ the ‘innovation’ of tourism, in diffusion terminology), nearby communities become more likely to also experience a similar process within the next few years because of their proximity to centres of growing tourism activity. This observation is also relevant to Christaller’s description of early tourists escaping to less-developed destinations when their old haunts become overcrowded (see the earlier ‘Destination cycle’ section), and thus links the process of national tourism development with the destination cycle. In other words, the destination cycle will first affect communities on the edge of existing tourism regions, and then gradually incorporate adjacent communities as the recreational hinterland spreads further into the countryside. The same effect can occur in a hierarchical way — as a country develops, funds may be made available to upgrade the airport or road connection to third-order regional cities, which then becomes a trigger factor that initiates the involvement stage.

Diffusion barriers and facilitators

This process, however, is not likely to continue indefinitely, in part because demand is not unlimited, but also because of barriers that terminate, slow, redirect or, more rarely, reverse the tourism diffusion process. These barriers can take numerous forms, the most common being the lack of attractions capable of carrying the destination beyond the exploration stage. Other barriers include community resistance, political boundaries (a good example is the boundary between North Korea and South Korea) and climate (e.g. 3S tourism can only develop within certain climatic parameters). Conversely, factors that can accelerate the diffusion process include an extensive area of tourism potential such as a beach-lined coast or an alpine valley, and upgraded transportation networks. It should be noted here that a road network is more likely to facilitate contagious diffusion, while an air network will facilitate hierarchical diffusion.

Model of national tourism development

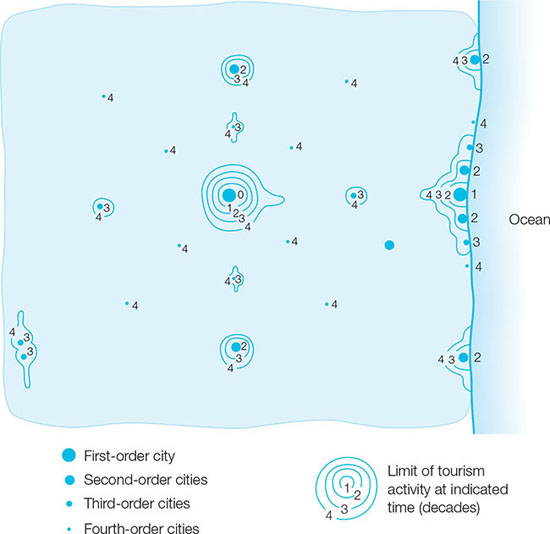

Figure 10.6 provides a model of national-scale tourism development that takes into account both hierarchical and contagious diffusion in a hypothetical country. 307The following sequence is depicted, with each interval representing, for the sake of illustration, a ten-year period.

Time 0: in this earliest phase of evolution, there is some inbound and domestic tourism activity, indicative of the involvement stage, in the capital city and main gateway. (It may be argued that all places prior to this time are in the exploration stage.)

Time 1: some years later, a small recreational hinterland forms around the capital city, and several ‘charming’ market villages start to emerge as excursionist-driven hyperdestinations. Meanwhile, tourism is introduced to a coastal city because of interest from the cruise ship industry and the presence of nearby beaches; this introduction may be spontaneous, or the result of a deliberate growth pole strategy.

Time 2: the recreational hinterland of the dominant city expands outward (= contagious diffusion), while tourism is introduced as a significant activity in several second-order cities (= hierarchical diffusion) now better connected to other cities by road and air. Concurrently, tourism development takes hold in other coastal communities because of their 3S resources, while the hinterland of the original resort expands further, both inland and along the coast.

Time 3: the pattern identified at Time 2 continues: recreational hinterlands expand and new places experience ‘involvement’; in addition, where physical geography permits, settlements in the interior become important as alpine tourist resorts.

Time 4: expansion continues, especially along transportation corridors, alpine valleys and the coastline, as well as in other interior fourth-order settlements. At this time, the entire country is a tourism landscape to the degree that some level of tourism activity is evident essentially everywhere.

FIGURE 10.6 Tourism development in a hypothetical country

Models such as figure 10.6 are potentially useful for predicting when and whether a particular place within a country is likely to enter the cycle process beyond the exploration stage. It is also valuable to those who are responsible for the management and planning of destination-countries, and in particular those who are seeking to direct this process. Like the Butler sequence, the ideal type depicted in the figure can probably be augmented by a constellation of subtypes that take into consideration different types of countries. These might include landlocked states (such as Zimbabwe and the Czech Republic), alpine states (such as Norway or Switzerland), very large states (such as Australia, Russia, Canada), emerging economies (such as Colombia and Papua New Guinea), centrally planned states (such as North Korea and Vietnam) and 3S-dependent SISODs (such as the Bahamas and Maldives).309

CHAPTER REVIEW

Although allusions to the destination cycle were already made in the 1960s, this concept is most closely associated with the S-shaped Butler sequence introduced in 1980. This integrative model proposes that destinations tend to pass through a series of stages: exploration, involvement, development, consolidation and stagnation. Depending on circumstances, the destination may then undergo continuing stagnation, decline and/or rejuvenation. One major implication of the model is that tourism, when driven by free market forces and sustained consumer demand, appears to contain within itself the seeds of its own destruction, as negative impacts accumulate and finally undermine the local tourism product as the stages progress. Applications of the intuitively appealing and simple Butler sequence to case study situations have revealed a broad adherence to the model, although most of these studies have also uncovered notable deviations. The results of many such applications therefore remain ambiguous. While criticised as well for being too deterministic and for not taking into account the existence and influence of sectors other than tourism in the destination, the Butler sequence has enormous value as an ‘ideal type’ against which real-life situations can be measured and benchmarked. It is also clear, however, that the model is applicable only at certain geographic scales, and should in general not be applied at the national scale except in the case of very small countries.

Whether the evolution of a destination is best described by the Butler sequence per se or by some variant, tourism managers should try to gain an understanding of the trigger factors and actions that induce significant change in a destination. These range from internal-intentional factors (the most favourable option) to those that are external-unintentional (the factors over which the destination has the least control, and hence the least favourable option). These factors, furthermore, can be generally classed as tourism stimulants or depressants, with the possibility that a stimulant in one place can be a depressant for another, and vice versa. In larger countries tourism development is best described as a combined hierarchical and contagious diffusion process that is distorted both positively and negatively by assorted barriers and opportunities. The destination cycle concept can be situated conveniently within this context of national tourism development, in that it is possible to anticipate whether, when and how a particular place is likely to move beyond the exploration stage of the cycle and into new phases.

SUMMARY OF KEY TERMS

SUMMARY OF KEY TERMS

Butler sequence the most widely cited and applied destination cycle model, which proposes five stages of cyclical evolution described by an S-shaped curve; these might then be followed by three other possible scenarios

Consolidation as local carrying capacities are exceeded, the rate of growth declines; the destination is now almost wholly dominated by tourism

Contagious diffusion spread occurs as a function of spatial proximity; the closer a site is to the place of the innovation’s origin, the sooner it is likely to be exposed to that phenomenon

Decline the scenario of declining visitor intake that is likely to ensue if no measures are taken to arrest the process of product deterioration and resident/tourist discontent

Destination cycle the theory that tourism-oriented places experience a repeated sequential process of birth, growth, maturation, and then possibly something similar to death, in their evolution as destinations310

Development the accelerated growth of tourism within a relatively short period of time, as this sector becomes a dominant feature of the destination economy and landscape

Exploration the earliest stage in the Butler sequence, characterised by few tourist arrivals and little impact associated with tourism

External-intentional actions deliberate actions that originate from outside the destination

External-unintentional actions actions that affect the destination, but originate from outside that destination, and are not intentional; these present the greatest challenges to destination managers

Hierarchical diffusion spread occurs through an urban or other hierarchy, usually from the largest to the smallest centres, independent of where these centres are located

Ideal type an idealised model of some phenomenon or process against which real-life situations can be measured and compared

Internal-intentional actions deliberate actions that originate from within the destination itself; the best case scenario for destinations in terms of control and management

Internal-unintentional actions actions that originate from within the destination, but are not deliberate

Involvement the second stage in the Butler sequence, where the local community responds to the opportunities created by tourism by offering specialised services; associated with a gradual increase in visitor numbers

Last chance tourism tourism activity and phenomena associated with people who want to visit a destination before the attraction disappears; associated with the loss of habitat, especially in coastal areas, due to climate change

Literary tourism any kind of tourism that is focused on a particular author, group of authors, or literary school; commonly regarded as a type of cultural tourism

Literary village a small settlement, usually rural, where tourism development is focused on some element of literary tourism

Matrix model of cycle trigger factors an eight-cell model that classifies the various actions that induce change in the evolution of tourism in a destination. Each of the following categories can be further divided into tourism stimulants and depressants

Rejuvenation the scenario of a renewed development-like growth that occurs if steps are taken to revitalise the tourism product offered by the destination

Spatial diffusion the process whereby some innovation or idea spreads from a point of origin to other locations; this model is more appropriate than the destination cycle to describe the development of tourism at the country level

Stagnation the stage in the Butler sequence wherein visitor numbers and tourism growth stagnate due to the deterioration of the product

QUESTIONS

QUESTIONS

What implications does the Butler sequence have for the change in visitor segments to a destination?

Why can the Butler sequence be referred to as the culmination of the cautionary platform?

Why are ‘ideal types’ such as the Butler sequence extremely useful to managers, even though they seldom if ever describe real-life situations?311

How can the recognition and understanding of ‘pre-exploration’ dynamics better position contemporary indigenous communities to avoid tourism development that breaches critical carrying capacity thresholds within their communities?

How does the phenomenon of last chance tourism complement or distort the tourism cycle?

Which of the eight cells that comprise the matrix model for classifying cycle trigger factors (as per figure 10.4) best describes the 2003 invasion of Iraq from the perspectives of Iraq itself and more generally, the Middle East?

How does the matrix model (see figure 10.4) complement and overlap with SWOT analysis to better understand and manage the dynamics of destination development?

How can the concepts of hierarchical and contagious diffusion complement the destination cycle model in helping to explain the process of tourism development at the national level?

How does figure 4.7 reveal the effects of hierarchical diffusion on the distribution of inbound tourism in Australia?

To what extent has proximity to the coast influenced the historical and contemporary development of tourism in Australia?

EXERCISES

EXERCISES