Tourist markets

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

outline and summarise the pattern of the major tourist market trends since 1950

describe the process that culminates in a decision to visit a particular destination

explain the need for, and the evaluative criteria involved in, the practice of market segmentation

discuss the strengths and limitations of major segmentation criteria, including country of origin and family lifecycle

differentiate between allocentric, midcentric and psychocentric forms of psychographic segmentation

analyse the various dimensions of motivation as a form of psychographic segmentation

discuss the types and importance of travel-related behavioural segmentation.

160

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

The previous chapter considered the variety and characteristics of attractions within the tourism system and also examined other supply-side components of the tourism industry, including travel agencies, transportation, tour operators, merchandisers and the hospitality sector. Chapter 6 returns to the demand side of the tourism equation by refocusing on the tourist. The next section reviews the major market trends in the tourism sector since 1950, and this is followed by a discussion of the destination selection process. The final section considers the importance of tourist market segmentation and examines the geographical, sociodemographical, psychographical and behavioural criteria that are commonly used in segmentation exercises.

TOURIST MARKET TRENDS

TOURIST MARKET TRENDS

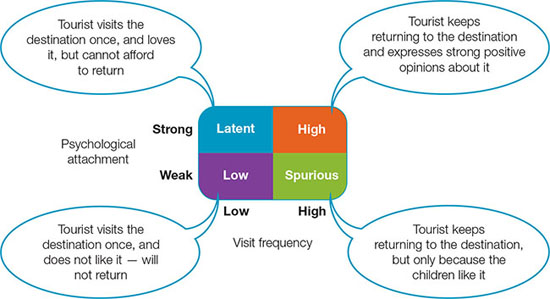

The tourist market is the overall group of consumers that engages in tourism-related travel. Since 1950 there have been several major trends in the evolution of this market and these are discussed below. Essentially, the overall tendency has been towards a gradually more focused level of market segmentation, which can be defined as the division of the tourist market into distinctive market segments presumed to be relatively consistent in terms of their members’ behaviour.

The democratisation of travel

The first trend was considered thoroughly in chapters 3 and 4 and can be described as the democratisation of travel. This emerged as increased discretionary time and income, among other factors, made domestic and then international travel accessible to the non-elite. Involvement in international travel grew rapidly in the Western world during the 1960s and 1970s, while a similar development occurred in certain Asian societies during the 1980s and 1990s. This was the classic era of global ‘mass tourism’, during which the tourism industry — like Thomas Cook 100 years earlier (see chapter 3) — perceived tourists as a more or less homogeneous market that demanded and consumed a very similar array of ‘cookie-cutter’ goods and services (see figure 6.1).

The emergence of simple market segmentation and multilevel segmentation

The second major trend emerged during the mid-1970s, as a large increase in oil prices made marketers and planners come to appreciate that a continuous growth scenario was not practical for every destination, and that some portions of the rapidly growing tourist market were more resistant to crisis conditions than others. This resulted in the practice of simple market segmentation, or the division of the tourist market into a minimal number of more or less homogenous subgroups based on certain common characteristics and/or behavioural patterns. Initially, marketers tried to isolate the smallest possible number of market segments in their desire to simplify marketing and product development efforts. Hence, broad market segments were treated as uniform entities (e.g. ‘women’ versus ‘men’, ‘old’ versus ‘young’, ‘Americans’ versus ‘Europeans’ and ‘Asians’).

By the 1980s the concept of market differentiation was refined through the practice of multilevel segmentation, which subdivided the basic market segments into more specific subgroups. For example, ‘Americans’ were divided into ‘East Coast’, 161‘West Coast’, ‘African–Americans’ and other relevant categories that recognised the diverse characteristics and behaviour otherwise disguised by simple market segmentation. Generational segments, such as the Millennials and Baby Boomers (see chapter 3), illustrate the idea of multilevel segmentation.

FIGURE 6.1 Tourist market trends since the 1950s

Niche markets and ‘markets of one’

By the 1990s the tourist market in Phase Four societies was more sophisticated and knowledgeable, having had three decades of mass travel experience. Consumers were aware of what the tourism experience could and should be, and thus demanded higher quality and more specialised products that cater to individual needs and tastes. The tourism industry has been able to fulfil these demands because of the internet, flexible production techniques and other technological innovations that have made catering to specialised tastes more feasible.

At the same time, the continued expansion of the tourist market has meant that traditionally invisible market segments (e.g. older gay couples, railway enthusiasts, stargazing ecotourists) are now much larger and thus constitute potentially lucrative markets for the tourism industry in their own right. This has led to the identification of niche markets encompassing relatively small groups of consumers with specialised characteristics and tastes, and to the targeting of these tourists through an appropriately specialised array of products within the tourism industry (see chapter 5). Space tourists (see chapter 2) and medical tourists (see chapter 4) are good examples of emerging niche markets. Extreme segmentation, based on markets of one, or segments consisting of just one individual, has also become a normal part of product development 162and marketing strategies in the early twenty-first century. This does not mean that mass marketing will disappear, especially given that attractions such as theme parks continue to emphasise their universal appeal, but simply that it will be technologically and financially feasible to tailor a product to just one consumer, in recognition of the fact that each individual, ultimately, is a unique market segment.

THE DESTINATION SELECTION PROCESS

THE DESTINATION SELECTION PROCESS

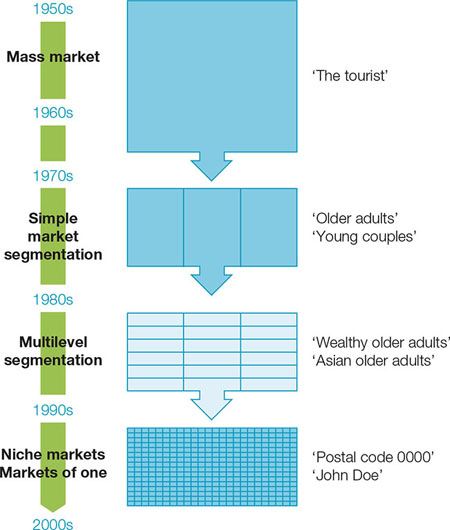

Further insight is gained into the importance of market segments and the methods that can be used to target these segments for marketing and management purposes by understanding the process whereby tourists arrive at a decision to visit one or more destinations. Destination marketers need to identify and understand the elements of this process that they can influence to achieve their visitation goals. They may, for example, have considerable influence over pull factors such as the design and distribution of brochures and maps, but no influence over push factors (see chapter 3) that induce people to travel. This is especially relevant to travel that is undertaken for leisure/recreation purposes, since the destination is usually predetermined in business and VFR tourism (see chapter 2). There are many destination selection models in the tourism literature (Um & Crompton 1990 is a classic), and figure 6.2 represents just one simplified way in which this process can be depicted. A logical place to begin is the decision to travel (1), which is driven by a combination of the ‘push’ factors discussed in chapter 3 and the potential tourist’s personality, motivations, culture, prior life experience (including previous travel), gender, health and education (box A in figure 6.2).

FIGURE 6.2 The destination selection process

The next stage (2) involves the evaluation of potential destinations from an ‘awareness set’ of all places known to the decision maker. This awareness set includes places that are known from prior direct or indirect experiences (that is, places known 163through past visits or through reading, media or word-of-mouth exchanges), as well as new places that emerge from subsequent information search. The latter search, as with the broader process of destination evaluation, is filtered by the personal characteristics listed in box A as well as push factors such as income, available time and family size. An open-minded, wealthy and well-educated person with no children, for example, is likely to undertake a very different information search and evaluation process than an inhibited person from an insular and proscriptive culture who also has a large family. The latter individual is likely to begin with a small awareness set and to rule out many destinations immediately because of the limitations just described (i.e. destinations that are too expensive, risky or child-intolerant). This requires assessment of the pull factors described in chapter 4, so that the final selection (3) will likely focus on an affordable, politically stable and accessible destination with many interesting attractions and a culture similar to that of the decision maker. The actual complexity of the evaluation process is evident in the fact that this often involves ‘final’ decisions that are subsequently revoked or altered by changing push and pull factors — such as being denied an expected pay increase, or news of a coup d’état in the destination to be visited. Similarly, a decision could be made as to which specific country to visit (e.g. New Zealand), but uncertainty may continue as to which destinations to visit within that country (e.g. Rotorua or Queenstown).

Feedback loops, such as occur when a tentative destination decision is rejected and the evaluation process is revisited, are found elsewhere in the model. This commonly occurs through the refinement of the destination image ‘pull’ factor as a result of direct experience (4) (e.g. the traveller had a wonderful vacation and thus carries a strongly positive destination image into the next evaluation process). The influence can also be indirect, as when the travel experience leads to transformations in the individual’s personality or attitudes (e.g. the traveller becomes more open to further travel to exotic destinations). Post-trip recollection and evaluation (5) also usually influence subsequent travel decisions.

Multiple decision makers

The destination selection process is further complicated by the fact that more than one person is often involved in the decision-making process. In such cases, purchase decisions both before and during the trip tend to require more time, as they often represent a compromise among group members. One study of Danish holiday decision-making identified ‘tweens’ (children aged 8 to 12) as extremely proactive and skilful negotiators who substantially influence decisions made during family vacations. They were found to take into account their own wishes but also those of other family members, engaging in successive rounds of compromise. The researchers, however, caution that the results may not be applicable to American tweens who they regard as more ‘parent-phobic’, self-confident and pestering (Blichfeldt et al. 2011).

TOURIST MARKET SEGMENTATION

TOURIST MARKET SEGMENTATION

There are at least eight factors that should be considered concurrently when evaluating the utility of market segmentation in any given situation, including:

Measurability. Can the target characteristics be measured in a meaningful and convenient way? Psychological criteria or high levels of ‘stress’, for example, are more difficult to quantify than age or education level.

Size. Is the market segment large enough to warrant attention? Very small groups, such as female war veterans over 85 years of age, may be insufficiently large to 164warrant attention by smaller companies or destinations that lack the capacity to engage in sophisticated niche marketing.

Homogeneity. Is the segmented group sufficiently distinct from other market segments? It may be, for example, that the 45–49 age group of adult males is not significantly different from the 50–54 age group, thereby eliminating any rationale for designating them as separate segments. A related consideration is whether the segmented group is internally homogeneous; if not, then like Generation Y (see chapter 3), it may need to be divided into separate segments.

Compatibility. Are the values, needs and wants of the segment compatible with the destination or company’s own values and planning strategies? There are instances in the Caribbean of specialised gay and lesbian cruise groups being confronted and threatened by conservative protesters who object to their presence.

Accessibility. How difficult is it to reach the target market? Sex tourists are relatively inaccessible because they are less likely to admit participation in socially unsanctioned activities. A more frequently encountered illustration is a small business in an English-speaking country that lacks the capacity to market its products overseas in languages other than English, and cannot communicate sufficiently with non–English-speaking tourists when they visit.

Actionability. Is the company or destination able to serve the needs of the market segment? For example, a wilderness lodge is usually not an appropriate venue for catering to gamblers or those with severe physical disabilities.

Durability. Will the segment exist for a long enough period of time to justify the pursuit of specialised marketing or management strategies? For example, the population of World War II veterans is now experiencing a high rate of attrition, and will be negligible in size by 2020. In contrast, baby boomers will constitute a lucrative market probably until the 2040s.

Relevance. Is there some underlying logic for targeting a particular segment? Segmentation on the basis of eye colour meets all the previous criteria, but there is no rational basis for thinking that eye colour influences consumer behaviour in any significant way.

The following sections discuss the major market segmentation criteria that are commonly used in the contemporary tourism sector, as well as those that are not widely employed but could be of potential value to tourism destinations and the tourism industry. These criteria include the box A characteristics in figure 6.2, which also influence the behaviour of individuals during and after the actual tourism experience. Ultimately, the appropriateness of particular segmentation criteria to a destination or business will depend on the conclusions reached in the evaluation of the eight factors outlined earlier.

Geographic segmentation

Geographic segmentation, the oldest and still the most popular basis for segmentation, takes into account spatial criteria such as country of birth, nationality or current residence of the consumer. Geographic segmentation declined during the 1980s as other segmentation criteria emerged, but it is now reasserting its former dominance through cost-effective GIS (geographic information systems) that facilitate the spatial analysis of tourism-related phenomena. GIS encompasses a variety of sophisticated computer software programs that assemble, store, manipulate, analyse and display spatially referenced information (Miller 2008). In a GIS package, the exact location of a person’s residence can be specified and related to other criteria relevant to that same 165location (e.g. income level, age structure, education levels, rainfall, road network). It is therefore possible to compile detailed combinations of market characteristics at a very high level of geographic resolution (e.g. individual households), making feasible the identification of the ‘markets of one’. Before GIS, the best level of resolution that could be hoped for was the equivalent of the postal code or census subdistrict.

Region and country of residence

The least sophisticated type of geographical analysis, but the simplest to compile, is regional residence, which has often been used as a surrogate for culture. Traditionally, tourism managers were content to differentiate their markets as ‘Asian’, ‘North American’ or ‘European’, because of low numbers and on the assumption that these regional markets exhibited relatively uniform patterns of behaviour. Most destinations and businesses now realise that such generalisations are simplistic and misleading, and prefer to differentiate at least by country of origin. In the case of Australia, for example, useful distinctions can be made between the mature Japanese and emerging Chinese inbound tourist markets on a range of tourism variables (see table 6.1 and the case study at the end of this chapter).

TABLE 6.1 Characteristics of Japanese and Chinese tourists visiting Australia, 2011

Source: Data derived from TRA (2012a)

| Criterion | Japanese inbound |

Chinese inbound |

| Repeat visitors (%) | 45 | 50 |

| Package tour visitors (%) | 43 | 40 |

| Backpackers (%) | 8 | 2 |

| Visiting New South Wales (%) Visiting Queensland (%) |

46 54 |

61 43 |

| Visitor-nights in homes of family or friends (%) | 10 | 22 |

| Average length of stay (nights) | 29 | 48 |

| Average total trip expenditure ($) Average expenditure per day ($) Expenditure on shopping for souvenirs and gifts (%) Expenditure on food/drink/accommodation (%) |

4681 161 6 22 |

7097 148 10 25 |

Subnational segmentation

It is appropriate to pursue geographical segmentation at a subnational level under two circumstances. First, larger countries tend to display important differences in behaviour from one internal region to another. Reduced cost and travel time, for example, position the California market as a stronger per capita source of tourists for Australia than New York or Florida.

The second factor is the number of people that travel to a destination from a particular country. A large number justifies the further division of that market into geographical subcomponents. For example, when the number of Chinese inbound tourists to Australia involved only a few thousand visitors, there was no compelling reason to make any further distinction by province of origin. However, as this number approaches 600 000 per year, it makes more sense to consider subnational criteria as a basis for market segmentation. Australian tourism authorities in the early 2000s focused their promotional efforts on the three large coastal ‘gateway’ markets 166of Beijing, Shanghai and Guangdong Province, but have more recently expanded their attention to the ‘secondary’ cities of Chongqing, Chengdu, Hangzhou, Nanjing, Shenyang, Shenzhen, Tianjin, Wuhan and Xiamen — all of which now display levels of affluence and sophistication similar to the original gateway markets (TRA 2012b).

Urban and rural origins

Useful insights may be gained by subdividing the tourist market on the basis of community size. Residents of large metropolitan areas have better access to media and the internet than other citizens, and more options to choose from at all stages of the destination buying process. Yet, within those same communities, the residents of gentrified inner-city neighbourhoods (e.g. North Sydney) are quite distinct from the residents of working-class outer suburbs (e.g. Parramatta) or the exurbs. Rural residents also have distinctive socioeconomic characteristics and behaviour. The urban–rural dichotomy is particularly important in less developed countries, where large metropolitan areas are likely to accommodate Phase Three or Four societies, while the countryside may reflect Phase Two characteristics (see chapter 3).

Sociodemographic segmentation

Sociodemographic segmentation variables include gender, age, family lifecycle, household education, occupation and income. Such variables are popular as segmentation criteria because they are easily collected (though respondents often withhold or misrepresent their income) and often associated with distinct types of behaviour.

Gender and gender orientation

Gender segmentation can be biological or sociocultural. If construed in strictly biological terms, gender is a readily observable and measurable criterion in most instances. Some activities (notably hunting) are an almost exclusively male domain (Lovelock 2008), while it is commonly alleged that ecotourists are disproportionately female (Weaver 2012). Females are also overrepresented as patrons of cultural events within Australia. During 2009–10, 19 per cent of Australian females 15 or older attended at least one theatre performance, compared with 13 per cent of males. Similar discrepancies were found in dance performances (13 and 7 per cent respectively) and musicals and operas (21 and 12 per cent) (ABS 2010). More subtly, female shoppers among Chinese visitors to the United States were found to place a higher value than males on communication with sales assistants to learn about products, and were more likely to express dissatisfaction with employees who did not engage with them accordingly (Xu & McGehee 2012). A survey of young and single Norwegian tourists revealed that females placed a much higher value on having a travel companion with whom to bond with, share experiences, and feel safe by night as well as day. Companionship among males, in contrast, was more superficial and transient (Heimtun & Abelsen 2012).

Gender can also be construed in terms of sexual orientation, and in this sense three stages and modes of development can be identified:

For many years, gay and lesbian tourism was either ignored by the tourism industry, or existed only as an informal fringe element. A ‘don’t ask, don’t tell’ attitude often prevailed, and gay expression was largely an ‘underground’ phenomenon.

With the liberalisation of sexual attitudes in the late twentieth century, this component of tourism became more visible through the emergence of specialised formal businesses and activities, particularly in the areas of accommodation (e.g. Turtle Cove Resort north of Cairns), tour operators, special events (e.g. the Gay Games) and the cruise ship sector.

167Since the late 1990s, the mainstream tourism industry has recognised the formidable purchasing power of gays and lesbians and has actively and openly pursued these markets. Some estimates suggest that the pink dollar accounts for 10–15 per cent of all consumer purchasing power. Destinations that are regarded as gay and lesbian ‘friendly’ include Sydney, San Francisco, London, Cape Town and Amsterdam. Sydney in particular is making a concerted bid to be recognised as a major gay and lesbian tourism destination, with its highly successful annual Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras, and its hosting of the Gay Games in 2002. The 2006 Mardi Gras attracted an estimated 450 000 participants, the majority of them heterosexual (Markwell & Tomsen 2010).

Gay and lesbian activists who resent the ‘invasion’ of gay environments by ‘mainstream’ tourists and businesses create their own ‘queer’ spaces where they can feel more empowered and less like performers at a show. This also reflects the high proportion of gay and lesbian people who do not feel safe travelling home from events such as the Mardi Gras due to the risk of attack from homophobic individuals (Markwell & Tomsen 2010).

Age and family lifecycle

Age and lifecycle considerations are popular criteria used in sociodemographic segmentation, since these can also have a significant bearing on consumer behaviour. Specific consideration is given in the following subsections to older adults, young adults and the traditional family lifecycle.

Older adults

Along with the emergence and growing acceptance of the gay and lesbian community, the rapid ageing of population is one of the dominant trends in contemporary Phase Four societies (see chapter 3). In the year 2010 the first baby boomers turned 65, and this has accelerated interest in the ‘older adult’ market segment. Traditionally, the 65+ market was assumed to require special services and facilities due to deteriorating physical condition. Their travel patterns, moreover, were believed to be influenced by the dual impact of reduced discretionary income and increased discretionary time caused by retirement. Finally, older adults were commonly perceived to constitute a single uniform market.

FIGURE 6.3 Older adults can be healthy and active tourists.

All these assumptions, however, are simplistic. In postindustrial Phase Four societies the 65-year age threshold is no longer a strict indicator of a person’s retirement status. Many companies facilitate early retirement options, while there is a concurrent trend to remove artificial age-of-retirement ceilings established during the industrial era. As for income, the current cohort of retirees is likely to be better off financially than their predecessors. In the early 2000s, the average Australian aged 55 to 64 had a net worth of $671 000 (Snoke, Kendig & O’Laughlin 2011). The assumption of physical deterioration is also false, as the 65-year-old of 2014 is in much better physical condition than their counterpart of 1950. A 65-year old male and female resident of New South Wales in 2009 could expect to live respectively to the ages of 83.7 and 86.8 (ABS 2011) (see figure 6.3). Finally, the assumption of market uniformity is also untenable, as demonstrated by cluster analysis of Australian 168older adults that differentiates between such substantial sub-segments as ‘enthusiastic connectors’ (about 20 per cent), ‘discovery and self-enhancers’ (26 per cent), ‘nostalgic travellers’ (29 per cent) and ‘reluctant travellers’ (25 per cent) (Cleaver Sellick 2004).

Young adults

In contrast to the 65+ cohort, Millennials and other young adults are often associated with higher levels of high-risk behaviour. This is especially evident in ritual events such as the ‘spring break’ phenomenon in the United States (Litvin 2009) and Australia’s ‘Schoolies Week’ (the celebration of a student’s completion of high school), which destination managers on the Gold Coast have attempted to convert into an orderly festival. Involving up to 30 000 young visitors, Schoolies Week is regarded with ambivalence by local residents (Weaver and Lawton 2013). There is parallel evidence, however, that young adults are also very interested in activities such as volunteer tourism that focus on self-improvement and the wellbeing of destination communities.

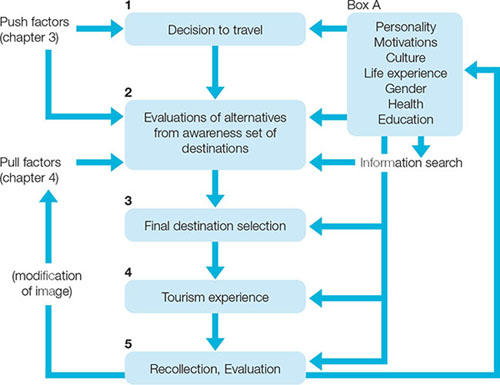

Family lifecycle

The family lifecycle (FLC) consists of a series of stages through which the majority of people in a Phase Four society are likely to pass during the time from young adulthood to death (see figure 6.4). The FLC stages are associated with particular age brackets, although there are many exceptions to this. All stages are also related to probable significant changes in family status, such as marriage, the raising of children, and the death of a partner. Retirement (i.e. change in work status) is also identified as an important stage transition.

FIGURE 6.4 Impact of non-conforming elements on the traditional family lifecycle

The importance of family lifecycle as a segmentation criterion is demonstrated by patterns of resort patronage in the United States identified by Choi, Lehto and Brey (2011). They found that couples with young children displayed the lowest levels of product loyalty, as expressed in modest emotional attachment, service satisfaction, employee regard, and perceived value for money. It is therefore more difficult to cultivate repeat visit intentions in this segment. Another finding was that young couples with no children do not rate employee regard as important but would prefer to develop personal rapport and friendships with staff. Resort employees therefore need to be trained to display different types of behaviour in the presence of different lifecycle segments. Finally, the non-traditional segment of single parents distinguished itself (unexpectedly) as the highest spending and least likely to give value for money as a reason for being loyal to the resort.

One major drawback of the traditional FLC is the increasing number of non-conforming people. Exceptions include permanently childless (or ‘childfree’) couples or those who have children relatively late in life, divorced people, family groupings that combine individuals from both marital partners (blended families), single parents, long-term gay and lesbian couples, multigenerational families, ‘permanent singles’, families where the children never leave the nest, older solitary survivors who marry and start new families with younger people (‘remarrieds’) and those whose spouses die at an early age. In essence, the conventional FLC reflects the traditional nuclear family of the 1950s and 1960s rather than the present era of familial diversity. In addition, even if individuals do conform to the FLC, this is not necessarily reflected in the composition of travel groups. People in relationships may decide to travel by themselves, or with a group of friends, while married couples may be accompanied by one or more parents, nephews or other married couples. Older children (e.g. 16-year-olds) often decline to accompany their younger siblings on annual family holidays. Another confounding factor is pet ownership and the increasing tendency of individuals in all stages of the FLC to regard their animals as family members (sometimes described as ‘companion animals’ or ‘fur babies’) and desirable travel companions who significantly influence and constrain their travel-related decisions (see Contemporary issue: Travelling with my best friend).

contemporary issue

![]() TRAVELLING WITH MY BEST FRIEND

TRAVELLING WITH MY BEST FRIEND

In developed countries such as the United Kingdom, United States and Taiwan, almost one-half of families own pets, but it is still unclear how pet ownership influences the travel behaviour of these families. This is important not only because of the magnitude of ownership, but also because owners often have deep attachments to their pets, often regard them as family members, and derive many psychological and other benefits from their company (Zilcha-Mano, Mikulincer & Shaver 2012). A recent study in Taiwan focused on 216 dog-owning domestic excursionists participating in various leisure activities (Hung, Chen & Peng 2012). The researchers found that owners who were strongly attached to their pets were highly motivated to include them in their travel plans. However, they faced structural constraints such as added financial and time costs, uncertainty about how their dog could participate in the activity, and the need to care for their animal.

170Interpersonal constraints included discomfort from the fact that other participants may not like dogs, the dog’s potential unfriendliness towards other people, and situations where they are the only one with a dog. Finally, specific constraints (i.e. specific to that particular dog) included limited self-control, unsuitability for the target activity, and a tendency to tire easily or to prefer the home environment. Thus, to participate in a mutually satisfying way with their dogs, owners recognised the need to obtain reliable and thorough information about the accommodation of pets, and to adjust their interpersonal relations so that they have more contact with pet-friendly co-participants, businesses and friends. They also appreciated the need to manage their time better to allow sufficient time to arrange an enjoyable experience for both themselves and their pets. Businesses such as ‘pet-friendly’ hotels that can provide these needs are likely to thrive as companion animals become an increasingly central part of the postmodern family unit.

Education, occupation and income

Education, occupation and income are often interrelated in terms of travel behaviour, since education generally influences occupation, which in turn influences income level. University education, for example, often leads to higher-paying professional employment. Income and education are often accessed indirectly by targeting neighbourhoods that display consistent characteristics with regard to these criteria. Not surprisingly, high levels of income and education, as well as professional occupations, are associated with increased tourism activity and in particular with a higher incidence of long-haul travel. One important implication is that high-income earners are usually less concerned with financial considerations when assessing destination options, and less likely to alter their travel plans in the event of an economic recession. Destinations and products that cater to high-income earners are therefore themselves less susceptible to recession-induced slumps in visitation. Distinctive forms of educational segmentation include international students, schoolies and participants in school excursions.

Race, ethnicity and religion

There is a general reluctance to ascribe distinctive character and behavioural traits on the basis of race, ethnicity or religion, and none of these are, therefore, commonly used for generic segmentation purposes. However, these are commonly used as segmentation criteria for specialised attractions that cater to particular racial, ethnic or religious groups. Examples include the marketing of heritage slavery sites in western Africa to African-Americans, and religious pilgrimages and festivals to applicable religious groups. In the case of Australia and New Zealand, it is likely that Indigenous Australian and Maori people constitute a growing portion of their respective domestic and outbound tourism sectors, yet research on ‘Aboriginal tourism’ and ‘Maori tourism’ are almost exclusively focused on the product side. We know almost nothing about the ‘Indigenous Australian tourist’ or ‘Maori tourist’ as distinct market segments. Moreover, as Australia and New Zealand move from a mainly Anglo-European to a multicultural society, these three criteria are likely to become more important to domestic tourism managers and marketers. For example, almost 529 000 and 476 000 Australians respectively indicated their affiliation with Buddhism and Islam in the 2011 census, but little is known about their behaviour as distinctive single or multiple market segments (ABS 2012).

Physical and mental condition

Persons with disabilities are often neglected or overlooked as a significant tourist segment, even though it is apparent that the number of such individuals is immense and 171their desire to travel as high as the general population’s (Yau, McKercher & Packer 2004; Stumbo & Pegg 2005). According to Australian Bureau of Statistics criteria, 18.5 per cent of the Australian population (or over 4 million people) were considered to have a disability in 2009 (ABS 2009). Four factors that indicate the need for tourism managers to pay greater attention to this segment are the:

increasing number of conditions that constitute an officially recognised ‘disability’

ageing of Phase Four populations (given that older adults still have a higher incidence of disabilities; for example disability levels increase to 40 per cent among Australians aged 65 to 69, and 88 per cent among those 90 or older (ABS 2009))

availability of technology to expedite travel by persons with disabilities

increasing recognition of the basic human rights, including the right to travel, of such persons.

Nevertheless, it is apparent that many tourism-related products and services still do not adequately address the needs of persons with disabilities (see Managing tourism: Catering to people with disabilities). Similar problems pertain to people who are overweight or obese (see Breakthrough tourism: Obesity as a tourism issue).

managing tourism

![]() CATERING TO PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES

CATERING TO PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES

Tourism can improve the quality of life for people with disabilities, and they comprise a potentially lucrative market for tourism businesses. Australia, however, has been slow to recognise and exploit this opportunity, despite the passing of the Disability Discrimination Act 1992. To better understand industry attitudes, Patterson, Darcy and Mönninghoff (2012) conducted semi-structured interviews with 32 Queensland-based operators listed as providing specialised products and services for people with disabilities. Over one-half of these operators stated that this segment accounted for less than 1 per cent of their business, and none gave a figure above 5 per cent. While operators of large hotels claimed compliance with regulations, only 1 per cent of their rooms on average were accessible and these were not often actually occupied by people with disabilities. Their existence, however, was necessary to successfully bid for any kind of conference or convention business, and they appealed to some older customers without disabilities. The need to comply with legal requirements was by far the main reason given by the operators for offering accessible facilities, although a significant minority did recognise the opportunity to increase their customer base and to benefit from good publicity. Only a few felt a moral obligation or sense of personal satisfaction in providing such facilities, and this was especially evident among smaller tour operators offering Great Barrier Reef experiences. None of the respondents offered any specialised staff training, which was related to the overall sentiment that people with disabilities represented only a very small portion of their customer base. Additional investments, accordingly, were regarded as prohibitively expensive and also impractical, given structural and design constraints in each operator’s current built environment. The researchers recommended that operators focus on providing renovations that cater to people with disabilities as well as others through, for example, larger bathrooms and wider doors.

172

![]() OBESITY AS A TOURISM ISSUE

OBESITY AS A TOURISM ISSUE

A growing proportion of the population in both the advanced and emerging economies is overweight or obese, and this poses a challenge to a tourism sector that celebrates and flaunts slenderness in its promotional material and in the design of its facilities. The issue is most salient in the airline industry, where seating has become a new contested space. Small and Harris (2012) found that obese passengers experience discomfort, embarrassment, annoyance, fear and frustration with the ‘one-size-fits-all’ seating practices followed by most airlines. Non-obese passengers, in contrast, express concerns over violation of rights (i.e. by the incursion of the obese passenger’s body into their seating space), anger, resentment, fear of injury and displeasure at contact with or proximity to obese persons. A few airlines require obese people to purchase two seats while a few others will allocate two seats for the price of one. Other suggested solutions have included ‘excess weight taxes’ and ‘pay by the pound’ policies. In 2013, the latter option was introduced by Samoa Air, a carrier based in American Samoa, a US territory that has one of the world’s highest rates of obesity (Sagapolutele & Perry 2013). Samoa Air has also created an ‘XL’ seating category for those passengers who weigh over 130 kilograms (Pearlman 2013). There are several cases where damages have been paid to people injured from being constricted next to obese passengers, but in general the industry has remained ‘innocent and silent’ on the issue, according to Small and Harris (2012). With 72 per cent of Australians expected to be overweight or obese by 2025, this is an evasion that airlines will not be able to afford much longer (Small & Harris 2012). Beyond the commercial implications of alienating various passenger segments, there is also the ongoing effort to recognise tourism — and associated transit experiences — as a basic human right. In such cases, whose rights should prevail — obese passengers or their non-obese fellow passengers?

Psychographic segmentation

The differentiation of the tourist market on the basis of psychological characteristics is referred to as psychographic segmentation. This can include a complex and diverse combination of factors, such as motivation, personality type, attitudes and perceptions, and needs. Psychographic profiles are often difficult to compile due to problems in identifying and measuring such characteristics. Individuals themselves are usually not aware of where they would fit within such a structure. Whereas most people can readily provide their income, age, or country of residence for a questionnaire, psychological profiles often have to be inferred through their responses to complex surveys, and then interpreted by the researcher. Whether they can then be placed into neat or stable categories, as with place of residence, is also highly questionable, as is the degree to which resulting profiles predict actual purchasing behaviour.

Also problematic is how much psychological characteristics can change, depending on circumstances. Personality type can change as a result of a person’s experiences, but this often occurs imperceptibly and in a way that is difficult to quantify, unlike changes of address or income level. Identification of a person’s ‘usual’ personality can 173also be misleading to the extent that an ‘alternate’ personality may emerge during a tourism experience, since this constitutes a change of routine for the traveller — that is, today’s partying schoolie can be tomorrow’s volunteer tourist. Because of such complexities, psychographic research usually requires more time and money than other types of segmentation, and often yields conflicting and uncertain results.

Psychographic typology

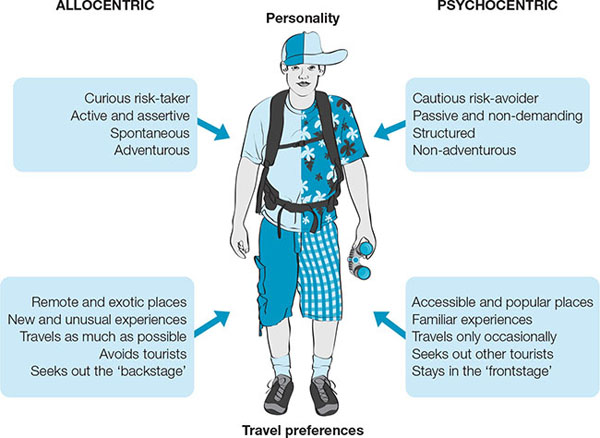

The idea of segmenting the tourist market according to levels of individual risk tolerance is largely associated with Plog (2005). His resilient allocentrics are intellectually curious travellers who enjoy immersing themselves in other cultures and willingly accept a high level of risk. They tend to make their own travel arrangements, travel by themselves or in pairs and are open to spontaneous changes in itinerary. They tend to avoid places that are heavily developed as tourist destinations, seeking out locales in which tourism is non-existent or incipient. Figure 6.5 provides a more detailed list of characteristics and tourism behaviour attributed to allocentrics.

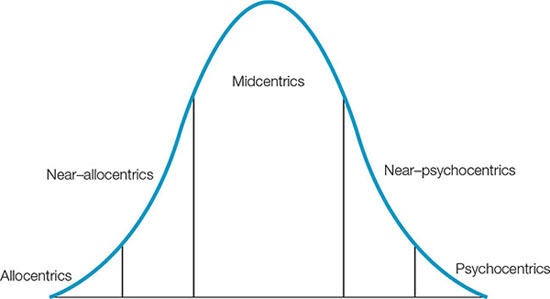

In contrast, psychocentrics are self-absorbed individuals who seek to minimise risk by visiting familiar and extensively developed destinations where a full array of familiar goods and services are available. According to Plog, those leaning toward the allocentric and psychocentric poles of the psychographic spectrum each account for about one-fifth of the US population. The remaining 60 per cent of the population, as depicted in figure 6.6, are midcentrics whose personalities combine elements of the allocentric and psychocentric dimensions. Typical midcentric behaviour, indicating a personal strategy of ‘mediated risk’, is an eagerness to attend a local cultural performance and sample the local cuisine, but parallel eagerness to have access to comfortable accommodation, hygienically prepared meals and a clean bathroom.

The typology has important implications for the evolution and management of tourism systems. Psychocentrics, for example, tend to visit well-established destinations dominated by large corporations and well-articulated tourism distribution systems, while allocentrics display an opposite tendency. A psychocentric would prefer to eat at McDonald’s, stay overnight at the Sheraton and visit a theme park, all mediated by a package tour, while an allocentric would eat at a local market stall, stay overnight in a small guesthouse situated away from the tourist district and explore the local rainforest.

The conceptual simplicity of the psychographic spectrum makes it very popular in tourism research. Recent applications include Weaver (2012), who found that visitors to a relatively isolated private protected area in South Carolina, United States, were mostly allocentrics. Critical from a management perspective is that these visitors — who are disproportionately older and female — were more likely to indicate loyalty to that protected area and a willingness to engage in activities to help its ecology. In another study, allocentrics and psychocentrics were both well represented among a sample of international and domestic guests at Malaysian homestay facilities, but the allocentrics were more likely to evaluate the experience as extraordinary and highly satisfying, and accordingly were more likely to want similar experiences in the future (Jamal, Othman & Muhammad 2011). These researchers therefore recommended that homestay managers target market their facilities to allocentric consumers.

Segmentation applications of the psychographic typology need to consider its shortcomings, which include the lack of a single reliable scale that would facilitate comparison across a variety of case studies. As stated earlier, the degree to which a person’s psychographic profile is fixed or can change with life experience is also unclear — does travel to an ‘allocentric’ destination make psychocentric people more open, or do they simply withdraw even further into their shell? Revealed mismatches between psychographic types and destinations (e.g. psychocentrics staying at Malaysian homestays) are common, and may indicate the influence of intervening 175factors such as financial necessity, time limitations, or preferences of other family members (Litvin 2006).

Motivation

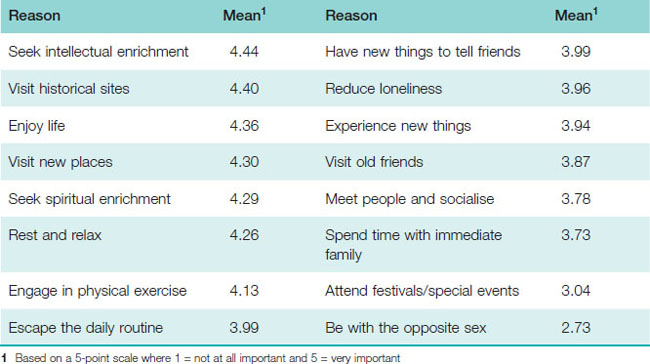

Travel motivation is different from travel purpose (see chapter 2) in that it indicates the intrinsic reasons the individual is embarking on a particular trip. Thus, a person might be travelling for VFR purposes, but the underlying motivation is to resolve a dispute with a parent, or to renew a relationship with a former partner. A stated pleasure or leisure purpose often disguises a deeper need to escape routine. In all these cases, the apparent motivation may itself have some even more fundamental psychological basis, such as the need for emotional satisfaction or spiritual fulfillment. Motivation is implicit in the psychographic spectrum, in that allocentrics are more driven by curiosity than psychocentrics, who in turn are more likely to be motivated by hedonism. Top motivations for older residents of Changsha, China (55 or older) who define as ‘frequent’ travellers (at least two leisure tourism trips per year) are depicted in table 6.2.

TABLE 6.2 Reasons for taking a holiday, frequently travelling Changsha residents (55+), 2011

Source: Chen & Gassner (2012)

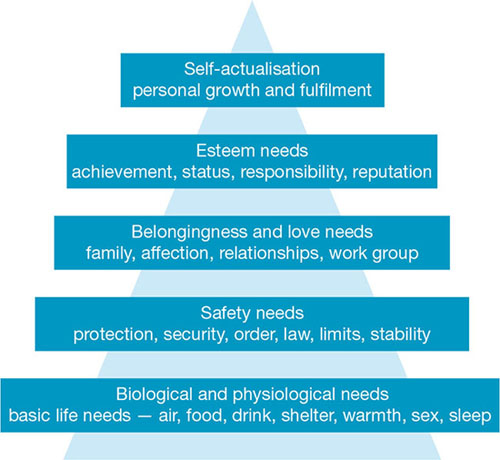

There are numerous theories and classification schemes associated with motivation. One of the best known is Maslow’s hierarchy of human needs (in Hsu & Huang 2008), which ranges from basic physiological needs (e.g. food, sleep, sex) to the needs for safety and security, love, esteem, self-actualisation, knowledge and understanding, and finally, aesthetics (see figure 6.7). A complex experience such as participation in volunteer tourism demonstrates how these needs can all factor into a single tourism experience. The volunteer tourist might be motivated by the need to achieve something important and to grow personally as a result. Being a member of a volunteer team fulfils a need to belong, while an experience is selected that is safe and provides for basic physiological needs.

Behavioural segmentation

The identification of distinct tourist markets on the basis of activities and other actions undertaken especially during the tourism experience is an exercise in behavioural segmentation. In a sense, it employs the outcomes of prior destination or product buying decisions as a basis for market segmentation, and therefore omits the non-travelling component of the population (unless non-travel behaviour is itself included as a ‘travel’ category). Basic behavioural criteria include:

travel occasion

destination coverage (including length of stay)

activity

repeat patronage and loyalty.

Travel occasion

Travel occasion is closely related to purpose. Occasion-based segmentation differentiates consumers according to the specific occasion that prompts them to visit a particular tourism product. Birthdays, anniversaries, funerals and other rites of passage are examples of individually-focused travel occasions, while Schoolies Week and sporting spectacles are mass participation variants. An intermediate example is the family reunion, which is becoming increasingly popular as a way of maintaining direct contact with extended families widely separated by geographical and generational drift. It has been estimated that 72 million Americans travel each year to participate in family reunions, and many destinations and businesses are providing specialised facilities and services to serve their needs (Kluin & Lehto 2012).

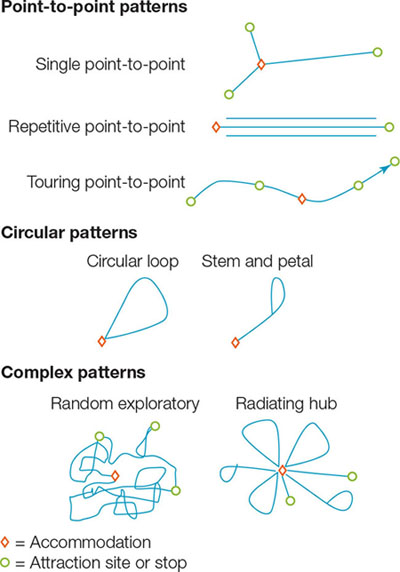

Destination coverage

Destination coverage can be expressed by length of stay, and also by the number of destinations (as opposed to stopovers and other transit experiences) that are visited during a particular trip. Visitors to Australia, for example, can be segmented by how 177much their visits are focused on a single state (as in the case of Japanese package tours to Queensland) or a multistate itinerary (as in the case of backpackers from Europe). Both single-destination and multi-destination trips usually display a great deal of variety with respect to destination coverage, as described by Lew and McKercher (2006) (see figure 6.8). Numerous implications follow from these variants, including the extent to which tourists are concentrated or dispersed within a destination, the length of time (and thus amount of money) spent in different parts of the country, the configuration of transit regions, and the types of services that are accessed during the tourism experience. Multi-destination itineraries continue to grow in popularity as countries and regions pursue mutually beneficial bilateral and multilateral destination marketing and development initiatives. An excellent Asia–Pacific example is the emergence of a formal Mekong Tourism brand that encourages cross-border travel within the participating countries of Cambodia, China (Guangxi and Yunnan Provinces only), Laos, Myanmar, Thailand and Vietnam (Semone & Kozak 2012).

Activity

Variables that can be segmented under the generic category of ‘activity’ include accommodation type, mode of transportation, total and per-day expenditure, attractions visited and types of tourist activities undertaken. An emerging topic of importance is the degree to which tourists behave in an environmentally and socially responsible manner during their travel (see chapter 11). Tourist activities, in particular, are extremely diverse. Relevant market segments in Australia include ecotourists, theme park visitors, honeymooners, beach bathers, bush walkers, visitors to Aboriginal sites and performances, backpackers (see Technology and tourism: Introducing the flashpacker), heritage tourists, festival attendees and wine tourists. Whether these activities are of primary or secondary importance to the relevant segment is also a critical factor.

A relevant issue is whether tourists are mainly interested in specific activities, and therefore choose their destination accordingly, or whether they are primarily interested in a particular destination, within which available activities are then pursued. The second scenario is less common than the first. This mainly involves tourists who are constrained by financial or time limitations to travel within their own state or country or, more rarely, who are motivated by patriotic considerations or a compelling desire to visit a particular destination that they encountered in a book or the media. The Queensland coastal resort community of Hervey Bay illustrates both scenarios. Some of its whale-watching tourists are there because they are primarily interested in that activity. Others are there because they are primarily interested in visiting Hervey Bay, and whale-watching happens to be one of the available activities.

technology and tourism

![]() INTRODUCING THE FLASHPACKER

INTRODUCING THE FLASHPACKER

Backpackers have long been a market segment of strategic interest for many destinations, and the advent of the information technology revolution has spawned an important variant known as flashpackers. These are backpackers who, during their travels, are hyper-connected to Facebook, blogs, Twitter and other social media that facilitate instantaneous communication within their social networks (Jarvis & Peel 2010). As such, the flashpacker combines the subcultures of backpackers and ‘digital nomads’ (i.e. people who use technology to facilitate a mobile lifestyle). An issue of interest to marketers is whether flashpackers are simply a sub-segment of the backpacker market, or distinctive enough to warrant their own target marketing strategies. Also, will they continue to diverge from other backpackers, or are they simply the vanguard of what the typical backpacker of the future will look like? Research on 493 backpackers in Cairns, Australia, sheds some light on these questions (Paris 2012). About 20 per cent were classified as flashpackers on the basis of higher technology use and expenditures during their travel. They were demographically distinctive in being more likely to be male and older (though still Gen Y), but were similar to other backpackers in their high levels of education, and student or part-time employment status. Being far more likely to carry a laptop and mobile phone, 90 per cent logged onto the internet at least once a day, compared with 75 per cent of other backpackers. They desired authentic and unique experiences, but were significantly more likely to agree that travelling alone is risky, time matters when travelling, carrying a laptop is an acceptable part of ‘real’ backpacking, and being on the internet a lot does not diminish the travel experience. Despite these differences, however, Paris (2012) identifies a common overall cultural model in which flashpackers represent the innovative future of backpacking. In this scenario, it is the ‘purists’ — preferring face-to-face communication with other backpackers — who will then form a new reactionary backpacker sub-culture.

It is important for destinations to determine what proportions of their visitors fall into each category in order to better understand both their markets and their competitors. In attracting tourists mainly interested in whale-watching, Hervey Bay is competing with destinations in other parts of the world (e.g. New Zealand, Canada) and potentially in other parts of Australia. In attracting tourists in the second category, Hervey Bay is competing with the Sunshine and Gold Coasts, as well as other destinations that happen to be located within Queensland but do not necessarily offer whale-watching.

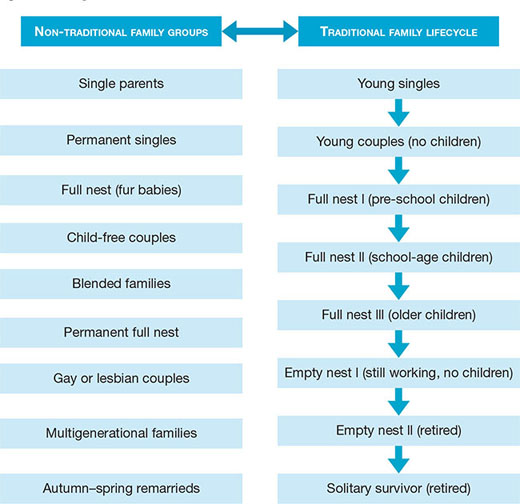

Repeat patronage and loyalty

As with any type of product, high levels of repeat visitation (i.e. repeat patronage) are regarded as evidence of a successful destination, hence the critical distinction between first-time and repeat visitors. One practical advantage of repeat visitation is the reduced need to invest resources into marketing campaigns, not only because the repeat visitors are returning anyway, but because these satisfied customers are more likely to provide free publicity through positive word-of-mouth and electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) 179contact with other potential visitors. Use frequency is an important segmentation variable that essentially quantifies repeat patronage by indicating the number of times that a product (e.g. a destination or an airline flight) is purchased over a given period of time. Frequent flyer and other repeat-user programs are perhaps the best example of an industry initiative that responds to and encourages high use frequency. Moreover, they provide an excellent database for carrying out relevant marketing and management exercises. At the opposite end of the continuum, there is increased interest in understanding the nontravel segment, or those defined as not having taken a recreational trip over a given period of time, usually 2 or 3 years. Litvin, Smith and Pitts (2013) emphasise the enormous size of this market (around 40 per cent of Australians, for example) and note that their generally more sedentary lifestyles constrain efforts to encourage a higher level of travel.

Repeat patronage and lengthy stays are often equated with product loyalty. However, the concept of loyalty goes beyond this single factor to incorporate the psychological attitudes towards the products that compel such behaviour. When both attitudinal and behavioural (repeat purchase) dimensions are taken into account, a four-cell loyalty matrix emerges (see figure 6.9):

Consumers who demonstrate a pattern of repeat visitation and express a high psychological attachment to a destination (or any other tourism-related product), including a willingness to recommend the product to others, belong in the ‘high’ loyalty category.

Conversely, those who have made only a single visit, and indicate negative attitudes about the destination, are assigned to the ‘low’ loyalty cell, as they are unlikely to visit again.

‘Spurious’ loyalty is a paradox, occurring when a pattern of repeat visitation is exhibited along with a weak psychological attachment. This could result when someone feels compelled to make repeat visits to a destination due to family or peer group pressure, or because financial limitations prohibit visits to more desired destinations.

‘Latent’ loyalty is also paradoxical, describing the opposite scenario where someone regards a destination very highly, but only makes a single visit. The commonest example of this behaviour is a ‘once-in-a-lifetime’ visit to an exotic but expensive location.

The loss of the spuriously loyal clientele usually does not indicate any serious problem for a business, since their visits are mainly a matter of habit, convenience or coercion rather than conviction. In contrast, high-loyalty visitors are highly valued by destinations because of their predictability, and because they are more likely to continue their patronage for longer even if the situation in the destination, or in their personal circumstances, begins to deteriorate (i.e. they are more resistant to the erosion of relevant push and pull factors). These tourists, then, constitute an important indicator group, in that the loss of this group’s patronage may show that the product is experiencing a very serious level of deterioration or change — as, for example, in association with changing destination lifecycle dynamics (see chapter 10). Failure to foster or retain high loyalty traits in some markets, however, may simply indicate a failure to understand cultural characteristics such as ‘face’ and ‘harmony’ that give rise to loyalty (Hoare & Butcher 2008).

181

CHAPTER REVIEW

Since the 1950s there has been a shift in the perception of the tourist market from a homogeneous group of consumers to increasingly specific or niche market segments. This has occurred in part because of the growing sophistication and size of the market, which has added complexity to the demand for tourism-related products and made it viable for operators to serve ever more specialised groups of consumers. In addition, technologies have emerged to readily identify these specialised segments and facilitate the development and marketing of appropriate niche tourism products. The culmination of this process has been the ability of marketers and managers to regard each customer as an individual segment, or market of one.

All consumers experience a similar decision-making process when selecting destinations and other tourism products. However, the specifics of the process (and subsequent tourism behaviour) vary according to many push and pull forces as well as personal characteristics such as culture, personality and motivations. Many of these forces and characteristics are therefore potentially useful as segmentation variables, though their relevance in any given situation depends on factors such as measurability, size, homogeneity and compatibility.

Four major categories of market segmentation are widely recognised. Geographic segmentation considers spatial criteria such as region or country of origin, subnational origins and the urban–rural distinction. This type of segmentation is the most commonly employed, and is becoming more sophisticated due to the development of GIS technologies. Sociodemographic segmentation includes gender, age, disability and family lifecycle as well as the highly interrelated criteria of education, occupation and income. Gay and lesbian tourists, along with retiring baby boomers and women, are three market segments that have attracted sustained industry attention due to their growth and purchasing power. Psychographic segmentation is the most difficult to identify. The distinction between allocentrics, psychocentrics and midcentrics is the best-known example, although motivation is also commonly used. Finally, behavioural segmentation considers such experiential factors as travel occasion, the number of destinations visited during a trip, activities, and repeat patronage and loyalty.

SUMMARY OF KEY TERMS

SUMMARY OF KEY TERMS

Allocentrics according to Plog’s typology, ‘other-centred’ tourists who enjoy exposing themselves to other cultures and new experiences, and are willing to take risks in this process

Behavioural segmentation the identification of tourist markets on the basis of activities and actions undertaken during the actual tourism experience

Family lifecycle (FLC) a sequence of stages through which the traditional nuclear family passes from early adulthood to the death of a spouse; each stage is associated with distinct patterns of tourism-related behaviour associated with changing family and financial circumstances

Flashpackers backpackers who are hyper-connected to technology during their travel, thereby creating behaviour that is substantially distinct from conventional backpackers

Gender segmentation the grouping of individuals into male and female categories, or according to sexual orientation

Geographic segmentation market segmentation carried out on the basis of the market’s origin region; can be carried out at various scales, including region (e.g. Asia), country (Germany), subnational unit (California, Queensland), or urban/rural182

GIS (geographic information systems) sophisticated computer software programs that facilitate the assembly, storage, manipulation, analysis and display of spatially referenced information

Loyalty the extent to which a product, such as a destination, is perceived in a positive way and repeatedly purchased by the consumer

Market segmentation the division of the tourist market into more or less homogenous subgroups, or tourist market segments, based on certain common characteristics and/or behavioural patterns

Market segments portions of the tourist market that are more or less distinct in their characteristics and/or behaviour

Markets of one an extreme form of market segmentation, in which individual consumers are recognised as distinct market segments

Midcentrics ‘average’ tourists whose personality type is a compromise between allocentric and psychocentric traits

Motivation the intrinsic reasons why the individual is embarking on a particular trip

Multilevel segmentation a refinement of simple market segmentation that further differentiates basic level segments

Niche markets highly specialised market segments

Pink dollar the purchasing power of gay and lesbian consumers, recognised to be much higher than the average purchasing power (sometimes used to describe the purchasing power of women)

Psychocentrics ‘self-centred’ tourists who prefer familiar and risk-averse experiences

Psychographic segmentation the differentiation of the tourist market on the basis of psychological and motivational characteristics such as personality, motivations and needs

Simple market segmentation the most basic form of market segmentation, involving the identification of a minimal number of basic market segments such as ‘female’ and ‘male’

Sociodemographic segmentation market segmentation based on social and demographic variables such as gender, age, family lifecycle, education, occupation and income

Tourist market the overall group of consumers that engages in some form of tourism-related travel

Zero-commission tours package tour arrangements in which no commissions are paid and profits are realised through aggressive and captive sales strategies; often associated with Chinese outbound tourism

QUESTIONS

QUESTIONS

For managers and marketers, what are the advantages and disadvantages, respectively, of treating the tourist market as a single entity or as a collection of markets of one?

To what extent do you believe that tourists in a given destination are obligated to behave in a manner that does not offend conservative local residents? Why?

To what extent should local residents be willing to compromise their own norms to satisfy tourists? Why?

What strengths and weaknesses are associated with ‘country of residence’ and ‘region of residence’ as criteria for identifying tourist market segments?183

Should airlines have the right to discriminate against obese people in their pricing and seating policies? Explain your reasoning.

-

What non-traditional family segments are becoming more widespread, and hence call into question the dominance of the traditional family lifecycle as a segmentation variable for the tourist market?

What different kinds of restraints might characterise these different non-traditional segments?

What criteria should a destination use in deciding whether to target specific racial, religious or ethnic groups?

What are the risks in targeting specific racial, religious or ethnic markets?

What difficulties are associated with the operationalisation of psychographic segmentation criteria?

What is the difference between trip purpose and trip motivation?

What are the strengths and weaknesses of each as segmentation criteria?

How can the loyalty matrix be operationalised to assist in the management and marketing of destinations?

EXERCISES

EXERCISES

Assume that you are the manager of a local theme park and that you have obtained funding to identify your market through the use of a questionnaire. Because these funds are very limited, you must keep your questionnaire to only two pages, which allows you to obtain no more than 15 customer characteristics.

List the 15 characteristics of your market base that you believe to be most important to the successful management of your attraction.

Indicate why you selected these particular characteristics.

Design the questionnaire.

Prepare an accompanying 500-word report that explains your choices as well as the metrics you use to measure each of these characteristics.

Design a 300-word travel brochure for a destination of your choice that attempts to attract as many visitors as possible by appealing to all levels of Maslow’s hierarchy (as shown in figure 6.7).

Explain how the brochure evokes this hierarchy.

FURTHER READING

FURTHER READING

Aitchison, C. (Ed.) 2011. Gender and Tourism: Social, Cultural and Spatial Perspectives. London: Routledge. A comprehensive perspective on the role of gender in tourism is provided in this text, which considers how gendered identities are represented in exclusionary spaces, practices and policies.

Darcy, S. 2013. Disability and Tourism. Wallingford, UK: CABI. Tourism businesses are increasingly recognising people with disabilities as a large, growing and viable market segment. This text addresses the definitions of disability and considers issues of demand, marketing, accessibility and future trends.

Guichard-Anguis, S. & Moon, O. (Eds) 2011. Japanese Tourism and Travel Culture. London: Routledge. Notwithstanding the rapid growth of the 184Chinese tourist market, Japanese tourists continue to situate as an important inbound market for many destinations, including Australia. This text considers the distinctive characteristics of Japanese tourism and their implications for destination management and marketing.

Kozak, M. & Decrop, A. (Eds) 2012. Handbook of Tourist Behavior. London: Routledge. The chapters in this text consider various aspects related to tourist decision-making and behaviour-related market segments. International case studies illustrate the concepts.

Schänzel, H., Yeoman, I. & Backer, E. (Eds) 2012. Family Tourism: Multidisciplinary Perspectives. Bristol: Channel View. Family travel is a prevalent type of tourist group, but one that is poorly understood. This is the first text to systematically analyse this critically important travel group segment, thereby providing a foundation for further study.

case study

![]() UNDERSTANDING CHINESE OUTBOUND TOURISTS

UNDERSTANDING CHINESE OUTBOUND TOURISTS

Australian tourism enterprises are focusing increasingly on Chinese outbound tourism because of its seemingly limitless growth potential. Targeted management and marketing strategies, however, need to correctly ‘read’ this market (or markets) so that satisfied visitors initiate a virtuous cycle of word-of-mouth recommendations and repeat visitation intentions. Such a cycle would reduce the costly need to recruit first-time visitors. Assuming that the Chinese have already been identified by a destination’s strategic plan as a desirable target segment, the ability to attract a desired share of this rapidly emerging market depends on exploiting a strategic ‘window of opportunity’ during which the market is properly identified, understood and cultivated. This is achieved by identifying and monitoring:

evolving push factors that motivate the Chinese to travel internationally

pull factors of the destination and the capacity of destination stakeholders to isolate and enhance those pull factors that appeal most effectively to these motivations

the image of the destination already held

external factors (e.g. financial, geopolitical, transportation, environmental) that might positively or negatively affect the resultant flow of Chinese outbound tourists to the destination

visitor satisfaction (Prideaux et al. 2012).

In assessing the resultant destination opportunities and the relevant market research, it is critical to emphasise that there are multiple Chinese markets. For example, Chinese visitors can be situated along a continuum from high volume/low yield (e.g. package tourists) to low volume/high yield (e.g. free and independent travellers (FITs)). At a relatively superficial level, a survey of higher yield Chinese tourists in the northern Queensland city of Cairns found that the Great Barrier Reef and other wildlife fulfilled motivations to 185experience Australia’s iconic natural environment, and produced high levels of satisfaction. Hence, an effective push–pull relationship is evident here that may help to explain an expected increase in Cairn’s inbound Chinese visitation from 70 000 in 2010 to more than 244 000 in 2015 if direct air services to China are opened (Prideaux et al. 2012). At a more psychographic level, a large survey of Chinese tour group participants from throughout Australia found very high ‘sensation seeking’ motivations based on a search for adventure, excitement, new experiences, meeting new people and exploring the local culture. However, ‘security consciousness’ was also widespread, and evident in concerns about personal safety (Chow & Murphy 2011). Weiler and Yu (2006) similarly identified a desire for more contact with locals (88 per cent) and a more flexible itinerary (93 per cent) among Chinese visitors to Victoria, but less interest in having a more challenging or adventurous holiday experience (49%). Younger visitors, however, had a much higher desire for adventure.

Within a wider context of attitudes, constraints and influences, Sparks and Pan (2009) found that Shanghai residents who were enquiring at travel agencies about overseas travel were influenced more by social norms and influences than personal attitudes; that is, they were more likely to intend to visit a place if friends, family, co-workers or travel agents thought it was a good idea to do so, rather than if they personally wanted to visit. Females were more susceptible to this social effect. Images about Australia were shaped primarily by television programs, while friends, the internet and magazines were also influential. Television played a particular role in shaping an image of Australia as inspiring, providing opportunities for self-enhancement, being a place where one can interact with locals, and providing shopping opportunities. As with the Victoria study, younger respondents (and especially those who were single) were more adventurous in their motivations and desired greater autonomy and flexibility. Important external barriers included exchange rates, distance and lack of fluency in English.

Qualitative research techniques are often especially useful for gaining insight into the complex arena of human attitudes and behaviour, and focus groups of Chinese visitors to Australia (including tourists from Hong Kong and Taiwan) revealed the extent to which dining out is regarded as a peak experience rather than just a mundane regular necessity (Chang, Kivela & Mak 2011). Participants explained that authentic Australian dining experiences were highly valued, and that a mediocre or unpleasant taste was not a problem as long as they could boast to friends and family that they had tasted crocodile or kangaroo. This represented for them the accrual of cultural capital. It was also very important to experience a diversity of food, and to receive a very high level of service that conformed to perceptions of Australia as a highly developed country. Simultaneously, they expected a good service attitude from attending staff, and did not mind the communication gap as long as a ‘cultural broker’ was present to explain (i.e. add value to) the various dishes. However, Chinese visitors — even adventurous and experienced travellers — still assessed exotic Australian foods according to Chinese standards of flavour and cooking method.

Zero-commission tours are a characteristic aspect of Chinese outbound tourism that can have negative effects on the tourists as well as destination stakeholders. These occur when inbound tour operators in a destination such as the Gold Coast charge no commissions to their Chinese outbound tourist operator 186counterparts, but in exchange receive their high volume business on monopolistic or similarly advantageous terms. To make a profit, the inbound operators take their clients to particular shops where aggressive sales tactics are used to sell often overpriced and low quality goods. Clients might also be charged entry fees to beaches and other free public spaces, or be forced to pay ‘tips’ to their tour guides. Such tours have been associated with perceived coercion and bullying, deception (for example, saying that the strict controlling of tourist actions is required because the streets are unsafe), poor quality, and ineffective complaint handling. This can result in damage to the destination brand in countries such as Thailand where such practices are common, and poor impressions of Chinese inbound operators on the part of other local companies who receive no benefits from the participating Chinese tourists (Zhang, Yan & Li 2009). Some Chinese tourist segments — such as first-time outbound travellers on a limited budget — may tolerate zero-commission tours because of their attractive low cost, but reputational damage to the destination may dissuade high-yield segments, who demand quality and flexibility.

QUESTIONS

What conclusions about the validity of Plog’s psychographic model to the Chinese outbound market can be reached based on the results from the empirical studies described in this case? Explain your reasons for reaching these conclusions.

Design a memorable and satisfying one-week itinerary to an Australian destination (e.g. Gold Coast, Outback, northern Queensland, Tasmania, etc.) for the Chinese FIT market, based on the characteristics of this market identified in the case study.

Identify the main constituent experiences of this itinerary and explain why they are likely to be memorable.

REFERENCES

REFERENCES

ABS 2009. Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia: Summary of Findings. Catalogue No. 4430.0. www.abs.gov.au. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

ABS 2010. Attendance at Selected Cultural Venues and Events. Catalogue No. 4114.0. www.abs.gov.au. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

ABS 2011. Australian Social Trends March 2011. Catalogue No. 4102. www.abs.gov.au. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

ABS 2012. Reflecting a Nation: Stories from the 2011 Census, 2012–2013. Catalogue No. 2071.0. www.abs.gov.au. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Blichfeldt, B., Pedersen, B., Johansen, A. & Hansen, L. 2011. ‘Tweens on Holidays. In Situ Decision-making from Children’s Perspective’. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism 11: 135–49.

Chang, R., Kivela, J. & Mak, A. 2011. ‘Attributes that Influence the Evaluation of Travel Dining Experience: When East meets West’. Tourism Management 32: 307–16.

Chen, S. & Gassner, M. 2012. ‘An Investigation of the Demographic, Psychological, Psychographic, and Behavioral Characteristics of Chinese Senior Leisure Travelers’. Journal of China Tourism Research 8: 123–45.

Choi, H-Y., Lehto, X. & Brey, E. 2011. ‘Investigating Resort Loyalty: Impacts of the Family Life Cycle’. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management 20: 121–41.187

Chow, I. & Murphy, P. 2011. ‘Predicting Intended and Actual Travel Behaviors: An Examination of Chinese Outbound Tourists to Australia’. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 28: 318–30.

Cleaver Sellick, M. 2004. ‘Discovery, Connection, Nostalgia: Key Travel Motives Within the Senior Market’. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 17: 55–71.

Hoare, R. & Butcher, K. 2008. ‘Do Chinese Cultural Values Affect Customer Satisfaction/Loyalty?’ International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 20: 156–71.

Heimtun, B. & Abelsen, B. 2012. ‘The Tourist Experience and Bonding’. Current Issues in Tourism 15: 425–39.

Hsu, C. & Huang, S. 2008. ‘Travel Motivation: A Critical Review of the Concept’s Development’. In Woodside, A. & Martin, D. (Eds) Tourism Management: Analysis, Behaviour and Strategy. Wallingford, UK: CABI, 14–27.

Hung, K-P., Chen, A. & Peng, N. 2012. ‘The Constraints for Taking Pets to Leisure Activities’. Annals of Tourism Research 39: 487–95.