Sustainable tourism

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

explain the concepts of ‘paradigm shift’ and ‘paradigm nudge’ and their relevance to contemporary tourism

indicate how conventional mass tourism is related to the dominant Western environmental paradigm

define sustainable tourism and show how this is related to both the dominant Western environmental paradigm, the green paradigm and sustainable development

identify key indicators that gauge sustainability and describe their strengths and shortcomings

list the reasons for the tourism industry’s adoption of the principle of sustainable tourism, and explain the advantages that larger companies have in its implementation

describe the patterns of sustainable tourism practice within the tourist industry

list examples of alternative tourism and discuss their advantages and disadvantages

explain how ecotourism differs from other nature-based tourism, and describe its three distinctive characteristics318

discuss the positive and negative arguments for encouraging tourism within protected areas

critique the broad context model of destination development scenarios as a framework for describing the evolutionary possibilities for tourist destinations.

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

As manifested in the Butler sequence, the destination cycle concept suggests that tourism driven only by free market forces degrades destinations and ultimately undermines itself if managers implement no remedial or precautionary measures during the growth of the sector, especially as development-stage dynamics come into effect. The desire to avoid these negative impacts and still derive positive economic, sociocultural and environmental impacts from tourism has given rise to the concept of sustainable tourism, or tourism that occurs within the carrying capacities of a particular destination. This chapter on sustainable tourism begins by examining the nature of paradigms and paradigm shifts, and considers the likelihood that the dominant scientific paradigm and its associated environmental perspective are in the process of being replaced or at least modified by exposure to a more environmentally sensitive ‘green paradigm’ mediated by the concept of ‘sustainable development’. This provides a context for understanding the emergence of ‘sustainable tourism’. After outlining potential key indicators of sustainable tourism and the shortcomings of indicator monitoring, we examine sustainability in the context of mass tourism. The reasons for the tourism industry’s interest in sustainability are considered, along with associated practices and measures. A critique of these developments is also provided. The ‘Sustainability and small-scale tourism’ section focuses on ‘alternative tourism’ and its various manifestations, as well as the problems that potentially accompany this counterpoint to mass tourism. Ecotourism, which can occur as either mass or alternative tourism, is then examined while the final section considers strategies that potentially improve the sustainability of destinations. It concludes with a broad context model of destination development scenarios that integrates these concepts and incorporates the Butler sequence.

A PARADIGM SHIFT?

A PARADIGM SHIFT?

Defined in its broadest sense, a paradigm is the entire constellation of beliefs, assumptions and values that underlie the prevailing way in which a society interprets reality at a given point in time. A paradigm can therefore also be described as a ‘worldview’ or ‘cosmology’. According to Kuhn (1962), a paradigm shift is likely to occur when the prevailing paradigm is faced with contradictions and anomalies in the real world that it cannot explain or accommodate. In response to this crisis of credibility, one or more alternative paradigms appear that seemingly resolve these contradictions and anomalies, and one of these gradually emerges as the new dominant paradigm for that society. The period from when the contradictions are first apparent to the replacement of the old paradigm with the competing paradigm can last for many decades, or even centuries. It is also important to note that the replacement of one dominant paradigm by another does not usually involve the disappearance of the formerly dominant paradigm. Rather, the latter can persist as a coexistent worldview retained by some groups or individuals. As well, the new dominant paradigm usually incorporates compatible (or at least non-contradictory) aspects of the old paradigm, and may even emerge as a synthesis between the old paradigm and other radically opposing worldviews that initially arise.319

Dominant Western environmental paradigm

Such a paradigm shift occurred in Europe during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. During this time, the Catholic Church was dominant, and its theological worldview held that the world was located in the centre of the universe, and that humans were created spontaneously in the image of God about 6000 years earlier. This theological paradigm was challenged by the discoveries of scientists such as Copernicus and Galileo, and gradually the theological paradigm was replaced by a scientific paradigm that offered coherent, logical and empirically verifiable explanations for the radical new theories proposed by these pioneers. Fundamentally, the scientific paradigm perceives the universe as a ‘giant machine’, not unlike an automobile, that can be ‘disassembled’ in order to see how it operates. Once these subcomponents and their functions are perfectly understood, then future events within the universe can be predicted with certainty. Underlying the scientific paradigm is the ‘scientific method’, which reveals knowledge through a rigorously objective procedure of hypothesis formulation and empirical testing (see chapter 12).

By the nineteenth century, science was established as the dominant paradigm within Europe, and then within the world as a whole through the colonial expansion of England, France, Spain and other major European powers. Accompanying the scientific paradigm was acceptance of the anthropocentric belief (a retention, perhaps, from the theological paradigm) that humans are the centre of all things and are apart from and superior to the natural environment. The latter, in this perspective, is seen as having no intrinsic value, but only extrinsic value in relation to its perceived usefulness for people. Thus, some types of woodland such as conifer plantations came to be valued because of their usefulness as a fuel and source of timber, while wetlands were assigned little or no value to the extent that they are perceived to be economically unproductive.

Related to this is the belief in ‘progress’, or the idea that the application of science and technology will result in a continuous improvement in the quality of human life. Ideologically, the parallel view that progress can best be attained through a growth-oriented capitalist economic system became widely accepted in certain countries such as the United Kingdom and the United States. This perspective emphasises the role of individual incentive and competitive free market forces that determine the value (defined in terms of contribution to GDP) of various elements of the natural environment, such as oil (high) and wetlands (low). These natural environment-related aspects of the scientific paradigm comprise the dominant Western environmental paradigm.

Contradictions

Since the mid-twentieth century, the dominant Western environmental paradigm has been confronted with a variety of anomalies and contradictions that challenge many of its fundamental assumptions about progress and nature. Ironically, many of these inconsistencies were revealed by science itself. For example, the field of physics demonstrated the apparently random and chaotic behaviour of subatomic particles, and revealed that the very act of observation can change the nature of these particles. Such findings call into doubt the universal applicability of the objective, mechanistic, deterministic worldview posited by the dominant Western environmental paradigm and science more generally.

At the same time, research in biology, geography and ecology shows that present levels of economic development and growth, deriving from notions of progress and 320dominance over nature, may be inconsistent with the world’s environmental carrying capacity. Processes and events that support this contention include:

a series of high-profile environmental disasters, including the Torrey Canyon oil tanker spill off the coast of the United Kingdom in 1967, the partial meltdown of the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant in the United States in 1979, the gas leak from the Union Carbide pesticide plant in Bhopal, India, in 1984, the nuclear power plant meltdown at Chernobyl, Ukraine, in 1986, the Exxon Valdez oil tanker spill off Alaska in 1989, Hurricane Katrina’s impact on New Orleans in 2005, and the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster of 2011

escalation in anthropogenic (human-induced) climate change, a phenomenon that was exposed widely to the global public through Al Gore’s Oscar-winning film An Inconvenient Truth and the successive progress reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)

increased incidence of dangerous pathogen mutations, caused in large part by the indiscriminate use of the antibiotics developed to control these disease-causing agents

rampant desertification and deforestation in the name of progress and economic development.

Some supporters of the dominant Western environmental paradigm, often described as ‘technological utopians’, argue that technology will solve all these problems as the necessity for solutions become apparent (e.g. scarcity, health concerns). Critics, however, point out that many of the problems are themselves caused by the same modern technologies (such as nuclear power and antibiotics) that claim to address other problems (such as depleted fossil fuels and increased incidence of disease). Critics also suggest that the damage to the environment may soon progress to a point of irreversibility, if this is not already the case.

The dominant Western environmental paradigm and tourism

The tourism sector has also been implicated in these developments. The criticisms of contemporary mass tourism raised in chapters 8 and 9, and the cautionary platform that articulated these criticisms, are reactions against a prevalent pattern of large-scale free market tourism development that is an outcome of the dominant Western environmental paradigm. As encapsulated in the Butler sequence (see chapter 10), this critique holds that the emphasis on unlimited free-market growth produces the contradiction of initially desirable tourist destinations that eventually self-destruct as they become overcrowded, polluted and crime-ridden, and hence increasingly less desirable to both tourists and residents.

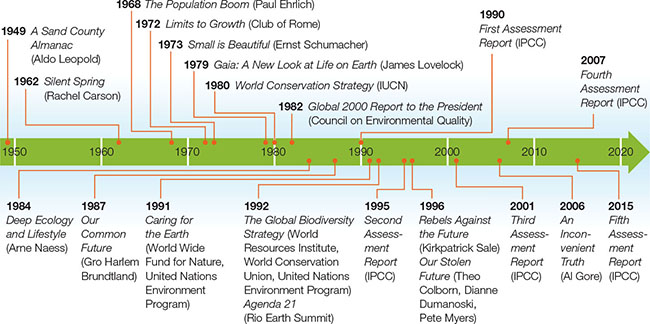

Towards a green paradigm

Criticism of the dominant Western environmental paradigm was made long before the present century — for example, in the writings of the American author Henry David Thoreau and the English author and social critic Charles Dickens. However, these were individual and isolated voices that initially did little to challenge the dominant paradigm and its damaging environmental or social impacts, especially since these problems were offset by demonstrable improvements in the physical wellbeing of societies undergoing the Industrial Revolution. Since 1950, the critique has gained momentum, in part because of the highly publicised environmental problems and disasters outlined earlier, and in part due to a sequence of high-profile publications that have both reflected and stimulated the post-1950 environmental movement (see figure 11.1). Challenges to the dominant Western environmental paradigm are also evident in allied perspectives such as contemporary feminism and the global reassertion of the rights of indigenous people, as well as through interest in the New Age movement. Some interpretations of the Bible, in addition, emphasise a philosophy of stewardship rather than dominion over nature.321

The growing crisis in the dominant Western environmental paradigm is, therefore, resulting in the articulation of a competing worldview that can be described in very general terms as the green paradigm. Both paradigms are depicted as contrasting ideal types in table 11.1, but it must be reiterated that a full shift to the green paradigm ideal type is unlikely. Rather, the actual (as opposed to ideal type) green paradigm of the future is likely to incorporate elements from each paradigm. This is evident in the emergence of corporate social responsibility as a business imperative that tries to amalgamate the core green principles of social responsibility and ethics with the core ‘corporate’ principles of profitability, competition and growth. There is, of course, considerable debate as to the compatibility and durability of such combinations.

FIGURE 11.1 Milestone publications in the modern environmental movement

TABLE 11.1 The dominant Western environmental paradigm and the green paradigm as contrasting ideal types

| Dominant Western environmental paradigm | Green paradigm |

| Humans are separate from nature | Humans are part of nature |

| Humans are superior to nature | Humans are equal with the rest of nature |

| Reality is objective | Reality is subjective |

| Reality can be compartmentalised | Reality is integrated and holistic |

| The future is predictable | The future is unpredictable |

| The universe has order | The universe is chaotic |

| The importance of rationality and reason | The importance of intuition |

| Hierarchical structures | Consensus-based structures |

| Competitive structures | Cooperative structures |

| Emphasis on the individual | Emphasis on the communal |

| Facilitation through capitalism | Facilitation through socialism |

| Linear progress and growth | Maintenance of a steady state |

| Use of hard technology | Use of soft technology |

| Patriarchal and male | Matriarchal and female |

Sustainable development

A hallmark in the emergence of the green paradigm as an alternative to conventional ways of thinking about the natural environment was the explicit recognition of sustainable development as a new guiding concept. Although the term was introduced in the early 1980s, it was the release of the Brundtland Report (Our Common Future) in 1987 that launched this idea into the forefront of the environmental debate. The Brundtland Report proposed the following definition of sustainable development:

Sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs (WCED 1987, p. 43).

This simple and enticing definition has gained widespread support from all sides of the environmental debate, and was employed as a central theme in the Rio Earth Summit of 1992 and its resultant Agenda 21 manifesto as well as in the sequel Johannesburg Summit of 2002 (‘Rio+10’) and the Rio Earth Summit of 2012 (‘Rio+20’). However, a closer scrutiny of the term reveals several difficulties. Some critics suggest that the term — like corporate social responsibility — is an oxymoron, with ‘sustainability’ (with its steady state implications) and ‘development’ (with its growth implications) being mutually exclusive. The widespread support that the term enjoys, therefore, may simply reflect the ease with which it can be appropriated by the supporters of various ideologies or platforms to perpetuate and legitimise their own perspective. A resultant danger, according to Mowforth and Munt (2009) and others, is that the term can be used for greenwashing purposes; that is, to convey an impression of environmental responsibility for a product or business that does not deserve the reputation for it.

Others, however, regard the semantic flexibility of sustainable development as an asset that recognises and is responsive to the complexity and diversity of the real world. Hunter (1997), for example, describes sustainable development as an adaptive paradigm that accommodates both weak and strong manifestations:

Weak sustainable development strategies are essentially anthropocentric and relevant to heavily modified environments (e.g. urban cores, intensively farmed areas), where human quality of life is a more realistic and relevant goal than, say, preserving rare species and their undisturbed habitats.

Strong sustainable development strategies are essentially biocentric and are warranted in relatively undisturbed environments such as Antarctica and most of the Amazon basin.

SUSTAINABLE TOURISM

SUSTAINABLE TOURISM

The term sustainable tourism became popular in the early 1990s following the release of the Brundtland Report, and the concept of sustainability has subsequently been embraced by all facets of the tourism industry. The term at its most basic represents a direct application of the sustainable development concept. Sustainable tourism, in this context, is tourism that meets the needs of present generations without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. In more practical operational terms, sustainable tourism can be regarded as tourism managed in such a way that:

it does not exceed the environmental, sociocultural or economic carrying capacity of a given destination, and

related environmental, sociocultural and economic costs are minimised while related environmental, sociocultural and economic benefits are maximised.

323

This inclusion of environmental, sociocultural and economic dimensions is often referred to as the triple bottom line approach. Weaver (2006) adds the caveat that even responsible operators may inadvertently operate on occasion in an unsustainable way, in which case the litmus test for a sustainable tourism operator is the willingness to redress the problem as soon as it is made apparent. Weaver also suggests that the definition should incorporate (as a parameter of economic sustainability) the need for operators to be financially sustainable, since tourism that is not financially viable is not likely to survive for long, no matter how viable it is from an environmental or sociocultural perspective. As with sustainable development, the term ‘sustainable tourism’ is susceptible to appropriation by those pursuing a particular political agenda, but is also amenable to weak and strong interpretations that adapt effectively to different kinds of destinations.

Indicators

Whether sustainability is perceived from a weak or strong perspective, criteria must be selected and monitored to determine whether sustainable tourism is present in a destination or not. The first step is to identify a set of appropriate environmental, sociocultural, economic and other relevant indicators (see Contemporary issue: Geopolitical sustainability and the quadruple bottom line), or variables that provide information about the status of some phenomenon (in this case, the level of sustainability), so that tourism and affiliated sectors can be managed accordingly. Since the early 1990s, the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) has played a lead role in identifying and ‘road testing’ tourism-related indicators. In the latest iteration of this process, the UNWTO in 2004 proposed 12 enduring baseline issues that are applicable to every destination (Antarctica may be an exception since it has no permanent resident community), and suggested indicators that allow for these issues to be measured (see table 11.2) (WTO 2004). The 2004 guidebook offers more than 500 indicators in total, inviting managers to select an array of indicators that is suitable for the specific circumstances of their own destination. To assist in the selection and implementation process, the guidebook supplements the suggested indicators with information about why the indicator is important, how it can be measured, and what benchmarks should be used. The result is the most comprehensive and flexible guidebook thus far for sustainable tourism, but one that is also hindered by its complexity and size as well as its failure to clearly describe the risks and challenges associated with the use of sustainable tourism indicators (Miller & Twining-Ward 2005).

contemporary issue

![]() GEOPOLITICAL SUSTAINABILITY AND THE QUADRUPLE BOTTOM LINE

GEOPOLITICAL SUSTAINABILITY AND THE QUADRUPLE BOTTOM LINE

School students visit Parliament House, Canberra

Sustainability is usually engaged in terms of its environmental, sociocultural and economic dimensions, but there is also a geopolitical component that deserves more attention (Weaver 2010b). Geopolitics refers to the interrelationships between space, territory and power that pervade international and domestic tourism systems. This is illustrated by the movements of tourists between countries, which have implications for the relationship between those countries that transcend and influence their economic, social and environmental impacts. Such movements, for example, can be used to initiate better bilateral relationships, as when a table tennis team from the United States visited China in the early 1970s as a gesture of friendship and 324reconciliation that ultimately led to better relations between the two countries. Similarly, tourism is a major component of the ‘growth triangle’ strategy that aims to promote mutually advantageous economic and cultural connections in the area where the boundaries of Singapore, Indonesia and Malaysia converge (Timothy & Teye 2004). In both examples, the deliberate use of tourism as a tool to improve bilateral or multilateral relationships can be seen as the pursuit of geopolitical sustainability. Such dynamics can also apply within a country. School field trips to visit iconic symbols of national identity in capital cities such as Canberra (Ritchie & Coughlan 2004), for example, are designed among other purposes to instil national pride and civic awareness in a culturally diverse population, thereby contributing to the long-term stability of Australia as a country. A more formal initiative is the Canadian federal government’s Encounters with Canada program, which allows more than 100 Canadian teenagers to travel to the national capital of Ottawa each week to meet teenagers from other parts of Canada and learn about key Canadian institutions and leadership opportunities (Encounters with Canada 2013). Because such outcomes can be seen to facilitate the more conventional economic, environmental and sociocultural parameters of sustainable tourism, it may be appropriate to include geopolitical sustainability as part of a new quadruple bottom line.

TABLE 11.2 UNWTO baseline issues and suggested indicators

Source: UNWTO (2004, p. 245)

| Baseline issue | Suggested indicators |

| 1. Local satisfaction with tourism |

|

| 2. Effects of tourism on communities |

|

| 3. Sustaining tourist satisfaction |

|

| 4. Tourism seasonality |

|

| 5. Economic benefits of tourism | |

| 6. Energy management |

|

| 7. Water availability and conservation |

|

| 8. Drinking water quality |

|

| 9. Sewage treatment (wastewater management) |

|

| 10. Solid waste management (garbage) |

|

| 11. Development control |

|

| 12. Controlling use intensity |

|

technology and tourism

![]() USING SOCIAL MEDIA TO GAUGE RESIDENT PERCEPTIONS

USING SOCIAL MEDIA TO GAUGE RESIDENT PERCEPTIONS

The tourism sector of the Maldives was shaken as thousands of Maldivians and foreigners watched a 2010 YouTube video of a ‘marriage ceremony’ in which a Swiss couple was unknowingly subjected to a barrage of insults in the native Dhivehi language from the so-called celebrant, a resort employee (Pidd 2010). Among the more than 12 000 commentaries posted across social media platforms after the incident was uploaded, about 10 per cent came from residents of the Maldives. This offers a unique opportunity for using netnography to gauge local reactions to a highly controversial tourism-related event (Shakeela & Weaver 2012). Almost all of the responses condemned the incident, often in strongly emotional language. The researchers analysed these responses and constructed an emoscape (‘emotional landscape’) that modelled these reactions. They found visceral reactions such as shame, anger or sadness; reflective fight responses that included calls for punishment 326of the celebrant and apology to the couple; sentiments about the event such as feelings that this happens on a regular basis; and cognitive interpretations that related to issues such as the ill-treatment of employees by resorts, the lack of professionalism among employees, and underlying political motivations of those who uploaded the video. The responses reflected a pervasive awareness of the vital role played by tourism in the national economy, and the subsequent need to protect the sector. Although it cannot be assumed that the responses represent Maldivian society overall, social media provides a means by which incidents can be witnessed almost immediately by millions, whose opinions can be easily disseminated to millions of others. Unlike interviews, surveys or other traditional sources of solicitation, social media encourages individuality, anonymity, and freedom of expression, and attracts responses — often impulsively — from those with strong feelings. Social media is therefore likely to become increasingly popular as a data source, and researchers will need to better understand how it differs from more traditional sources of solicitation.

Challenges of using indicators

Even if the UNWTO provides an indicator selection that adequately reflects the diversity of variables that need to be considered by destination managers, several operational challenges must still be confronted that further attest to the difficulties of undertaking such a task in complex tourism systems, including:

obtaining adequate stakeholder participation and agreement, including community input and approval (Miller & Twining-Ward 2005)

fuzzy boundaries between tourism and other sectors (see chapter 1), which make it difficult to determine the degree to which certain impacts can be attributed to tourism

difficulties in identifying indirect and especially induced impacts, such as the unsustainable construction of housing for workers attracted to an otherwise internally sustainable hotel

discontinuities between cause and effect through both time and space, whereby a negative impact in a destination such as E. coli appearing in the water may be caused by unsustainable tourism activity that occurred one month earlier and 50 kilometres upstream

incompatibility between the long-term timeframe of indicator monitoring and the short-term (and unpredictable) timeframe of the political processes that support monitoring

nonlinear relationships between cause and effect, so that a given input into a system does not necessarily result in a comparable or proportional output that can be reliably predicted. This is illustrated by the avalanche effect, in which a small input that caused no apparent problems in the past (e.g. another snowflake added to a snow bank), becomes a tipping point and triggers massive change in the system (e.g. an avalanche).

lack of knowledge about the benchmark and threshold values that indicate sustainability for a particular destination. A benchmark is a value against which the performance of an indicator can be assessed. The benchmark may be the same as a threshold, which is a critical value or value range beyond which the carrying capacity is being exceeded.

potential incompatibility between environmental and social or cultural sustainability, as when a strictly protected national park safeguards an endangered ecosystem but displaces a local human community

lack of a coordinated approach among destinations to trial generic indicators (see Managing tourism: Global observatories of sustainable tourism)327

managing tourism

![]() GLOBAL OBSERVATORIES OF SUSTAINABLE TOURISM

GLOBAL OBSERVATORIES OF SUSTAINABLE TOURISM

A major problem in implementing sustainable tourism is the difficulty in designating an adequate variety of coordinated locations where trial indicators (see table 11.2) can be systematically monitored, measured and assessed over a sufficient period of time. To overcome this obstacle, the UNWTO in 2004 introduced the Global Observatory of Sustainable Tourism (GOST) initiative to establish a long-term network of local sites where these activities can be undertaken. Since then, five observatories have been established in China alone to assist policy makers and industry to better plan and manage the country’s burgeoning tourism sector (UNWTO 2011). The five locations were carefully selected to represent a diversity of destination types. They include densely populated urban areas such as the city of Chengdu, where tourism attracts millions of domestic tourists, creates 600 000 direct jobs and generates 8 per cent of local gross national product (GNP) (UNWTO 2012). Because of the logistical difficulties in monitoring an entire city of 5 million residents, special observation sites have been set up at Sansheng Village, a semi-rural area famous for its flowers, and Kuanzhai Alley, an inner city historical district of restored hutongs (alleys) offering shops, restaurants and nightlife. At the other end of the spectrum, an observatory has also been established in the Kanas Lake Nature Reserve, a semi-wilderness protected area which each year receives over one million mainly domestic tourists. All five Chinese observatories are monitored by a specialised centre at Sun Yat-sen University in Guangzhou. With other observatories opened or planned in Montenegro, the Philippines and Saudi Arabia, the initiative will attempt to define best practice for a range of destinations, facilitate information exchange between destinations, and develop effective reporting mechanisms and training methods. This embryonic global network is also intended to help travel agencies and tour operators, as well as consumers, choose the most sustainable suppliers for their distribution chains.

SUSTAINABILITY AND MASS TOURISM

SUSTAINABILITY AND MASS TOURISM

Much of the early attention to sustainable tourism was focused on small-scale and low-intensity situations (see the following section), but its relevance to mass tourism is arguably more important. This is because the latter accounts for most global tourism activity, and most activity that has been evaluated as being ‘unsustainable’. The following discussion considers why the mass tourism industry should be interested in becoming more sustainable, and outlines current practices and measures that reflect apparent adherence to sustainable tourism.

Reasons for adoption

Several factors justify the adoption of the sustainability concept and sustainable practices within the mainstream tourism industry, in addition to the availability of a 328weak approach to sustainability that is relatively unthreatening to businesses. These include:

ethical considerations

the growth of the ‘green traveller’ market

the profitability of sustainability

conducive economies of scale.

Ethical considerations

One school of thought is that corporations should pursue sustainability because ethical behaviour is what society expects from entities that exercise great power over the environment and culture, even if such expectations are not enshrined in the law. This is the essence of corporate social responsibility. For some executives and managers, this may be motivated by religious fiat (e.g. the Golden Rule), while for others it may reflect an attitude of enlightened self-interest; that is, a belief that a failure to behave ethically will at some point result in a negative public image or consumer boycotts, or otherwise negatively affect a tourism business’s profitability by triggering the later stages of the Butler sequence.

Growth of the green consumer market

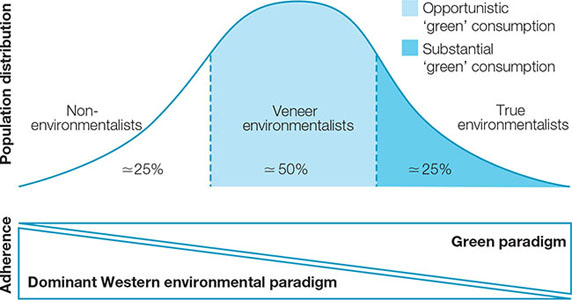

As a consequence of the expanding influence of the environmental movement, there is growing evidence that consumers are becoming more discerning, sophisticated and responsible when it comes to purchasing decisions and behaviour. In Phase Four societies such as Australia, the United States and the United Kingdom, various surveys suggest that approximately one-quarter of consumers can be described as ‘true’ green consumers, meaning that environmental and social considerations exert a major influence on their purchasing behaviour (see figure 11.2). True green consumers, to a greater or lesser extent, are described as such because they are willing to make inconvenient concessions — of cost or time, for example — for the sake of environmentally responsible behaviour (Weaver 2006). They are, for example, more willing to pay extra for ‘environmentally friendly’ food and cars, and believe that government should spend more of its budget on social and environmental issues.

FIGURE 11.2 Environmentalism-related population clusters

A larger group, consisting of about one-half of the population, includes marginal or ‘veneer’ green consumers. These people express concern about environmental issues but tend to purchase environmentally friendly goods and services only if it is convenient, as for example if the latter are priced competitively against comparable conventional goods and services. However, many will behave temporarily or permanently like ‘true’ green consumers once convinced that an environmental crisis is at hand, or if the adoption of such behaviour becomes less inconvenient. Business ignores this diverse phenomenon of emergent green consumerism at its peril, particularly since these attitudes and behaviour within society were virtually nonexistent before the emergence of the environmental movement after 1950. This trend lends credence to the theory of a contemporary paradigm shift. One financial indication is the growth in socially responsible investment (SRI) portfolios, whose assets in the United States alone increased in value from about US$40 billion in 1984 to US$3.74 trillion in 2012, or about 11 per cent of all professionally managed funds (US Social Investment Forum 2012).

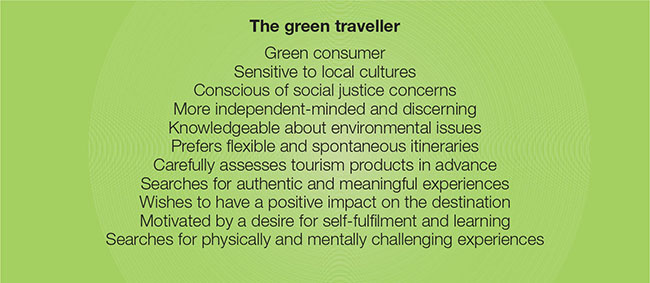

There is growing evidence that true green consumerism is manifest within tourism through the emergence of the green traveller segment, the ideal type of which is depicted in figure 11.3. Empirical evidence suggests that this was still a small segment of the overall tourist market in the early 2000s — around one per cent — but one which, like green consumerism more generally, is rapidly growing and over-represented with regard to high levels of income and education (Leslie 2012). However, there is also countervailing evidence which suggests that many people still tend to relax their level of moral behaviour during holiday travel (Dolnicar & Leisch 2008).

FIGURE 11.3 Characteristics of the green traveller

Profitability of sustainability

Notwithstanding the ambiguities in consumer behaviour, there is growing empirical evidence that ‘going green’ is a sound business decision in the tourism and hospitality sectors (Bohdanowicz 2009, Zhang, Joglekar & Verma 2010). Beyond an enhanced ability to attract specialised green travellers, the inherent profitability of many related activities is a major incentive for conventional businesses to become more involved in sustainability. Reduced energy consumption, for example, is a tangible long-term direct cost saving, as is the recycling of certain kinds of materials, especially given the escalating costs of conventional resources and the concomitant reductions in renewable resource costs. The increasingly ubiquitous hotel linen and towel reuse programs — provided 330that they are well designed — require minimal investment costs but attract high levels of guest participation that yield substantial reductions in water, energy and labour costs (Goldstein, Cialdini & Griskevicius 2008, Mair & Bergin-Seers 2010).

Conducive economies of scale

Larger corporations are better positioned in many ways than their small-scale counterparts to implement and profit from sustainable tourism measures. Economies of scale allow big businesses to allocate resources to fund specialised job positions that address sustainability-related issues (e.g. environmental officer, community relations officer), as well as relevant staff training, public education programs and comprehensive environmental audits. Cost-effective recycling and reduction programs are feasible because of the high levels of resource and energy consumption, while vertical and horizontal integration (see chapter 5) allow a company so structured to coordinate its sustainability efforts across a broad array of backward and forward linkages. Because of the volume of business they generate, these companies can also exert pressure on external suppliers to ‘go green’, thereby making a significant indirect contribution to sustainability. The major transnational hotel chain Marriott, to illustrate, established an Executive Green Council in 2007 to systematically reduce the company’s ecological footprint, ‘green’ its multi-billion dollar distribution chain, educate guests and employees, and participate in the preservation of natural habitat worldwide (Marriott 2013).

Practices

Sustainability-related patterns within the conventional mass tourism industry can be summarised as follows.

The rhetoric of sustainability has been formally and wholeheartedly embraced by corporations, industry groups and peak organisations such as the UNWTO.

Formal institutional mechanisms have been initiated throughout the sector to stimulate and facilitate the collective pursuit of sustainable tourism. These include the Cruise Industry Charitable Foundation (www.cruisefoundation.org), the International Tourism Partnership (www.tourismpartnership.org) and the Tour Operators Initiative (TOI) for Sustainable Tourism Development (www.toinitiative.org). Most sectors have also now introduced sustainability-related codes of practice.

Each sector has been led by a small number of high-profile corporate innovators. These include British Airways and American Airlines among air carriers; Marriott, Starwood and Grecotel among accommodation providers; and TUI among outbound tour operators.

Sustainability measures adopted by these leaders and other companies focus on activities that increase profits and lower costs in the short and medium term (e.g. high-volume recycling of glass and aluminium, energy use reduction, cogeneration — see Breakthrough tourism: Biofuel takes off), encourage brand visibility (sponsor tourism awards such as the WTTC Tourism for Tomorrow Awards) and are not expensive to implement (e.g. linen reuse signs in hotel bathrooms).

Although basic practices such as recycling and energy efficient retrofitting have become standard practice because of their cost-saving implications and/or regulatory compliance, a high level of unawareness and noninvolvement remains within each sector (beyond the high-profile activities of sector leaders) as to the array of possible sustainability practices.

High-level quality control mechanisms, such as third-party verified certification programs, have not yet been widely adopted.331

breakthrough tourism

![]() BIOFUEL TAKES OFF

BIOFUEL TAKES OFF

For the past few years, several major airlines have been experimenting with aviation biofuel as a supplement or substitute for conventional fossil fuels. Beyond designing more fuel-efficient aircraft, biofuels are the most effective way for the industry to reduce its carbon footprint and energy costs, which are otherwise expected to both increase substantially, in tandem with the anticipated growth in tourism demand. Among the more promising bio-sources are the jatropha and camelina plants, algae, and waste cooking oil. Biofuel still typically accounts for only a small portion of an aircraft’s total fuel load, although Finnair has successfully flown an Airbus A319 between Amsterdam and Helsinki with 50 per cent of its load consisting of used cooking oil (GreenAir 2011). Environmentally conscious airlines — including Qantas, Air New Zealand and Singapore Airlines — have formed the Sustainable Aviation Fuel Users Group (SAFUG) to ‘advance the development, certification, and commercial use’ of such fuels, and to do so in such a way as to be non-competitive with food production and protective of biodiversity (SAFUG 2013). The group cautioned that the use of biofuel should also not require any fundamental changes to aircraft engines or distribution systems, as this would involve high investment costs and impact on resources. Although advocates hail biofuel as the future of aviation, sceptics point out that environmental damage and diversion from food production will indeed occur to meet projected biofuel demand. This includes the European Union’s target of having 10 per cent of all its petrol and diesel derived from renewable sources by 2020, which some scientists believe would require 4.5 million hectares of land, an area two-thirds the size of Tasmania (EurActiv 2013). Reduced air travel, for many biofuel opponents, is the only viable way to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, but this option is not supported by current consumer attitudes or behaviour. A promising compromise is to focus on biofuels from algae and waste by-products (e.g. cooking oil) that do not require the transformation of existing agricultural food systems or the clearance of rainforest and other natural ecosystems to grow biofuel crops such as jatropha.

While significant and demonstrable sustainability-related progress has been achieved in the conventional tourism industry since the early 1990s, this progress is uneven and indicates a ‘veneer’ pattern of sustainability that responds to and parallels the dominance of veneer green consumerism within contemporary society (see figure 11.2). By this logic, the lack of a ‘deep’ commitment, which could for example be expressed in a voluntary decision by industry to declare a moratorium on tourism development in some destinations, is not evident mainly because there is not yet widespread public agitation for such a radically biocentric policy shift. The true green traveller segment, in effect, is not (yet) large or influential enough to fundamentally change the way industry operates, and the adoption of green practices by tourism businesses is still based mainly on bottom-line financial considerations. Notwithstanding the accompanying ethical rhetoric, these practices do not contradict or undermine existing capitalist premises about profitability, competition and growth. Hence, they are indicative 332of paradigm nudge — that is, the opportunistic adaptation of the existing capitalist worldview to changing circumstances — rather than an ethically-focused paradigm shift (Weaver 2007).

Quality control

A critical issue in the pursuit of sustainable tourism is the conveyance of assurance, through quality control mechanisms (or quality assurance mechanisms), that a particular hotel, ski resort, tour operator or carrier is as environmentally or socially sustainable as it claims to be. Codes of practice and ecolabels are two different quality control mechanisms that attempt to provide this assurance in the tourism industry.

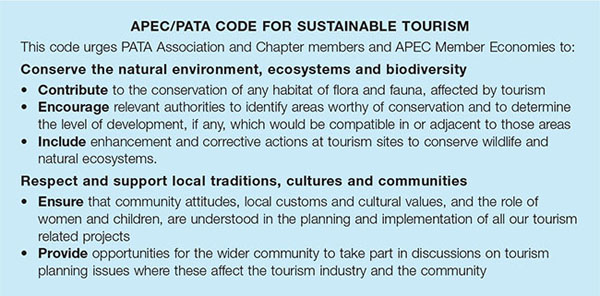

Codes of practice

The adoption of ‘green’ codes of practice, conduct or ethics is one of the most widespread and visible sustainability initiatives undertaken by the tourism industry. Examples include the:

Code of Ethics and Guidelines for Sustainable Tourism (Tourism Industry Association of Canada)

Environmental Codes of Conduct for Tourism (United Nations Environment Program)

Sustainable Tourism Principles (Worldwide Fund for Nature and Tourism Concern)

APEC/PATA Code for Sustainable Tourism

Environmental Charter for Ski Areas (National Ski Areas Association).

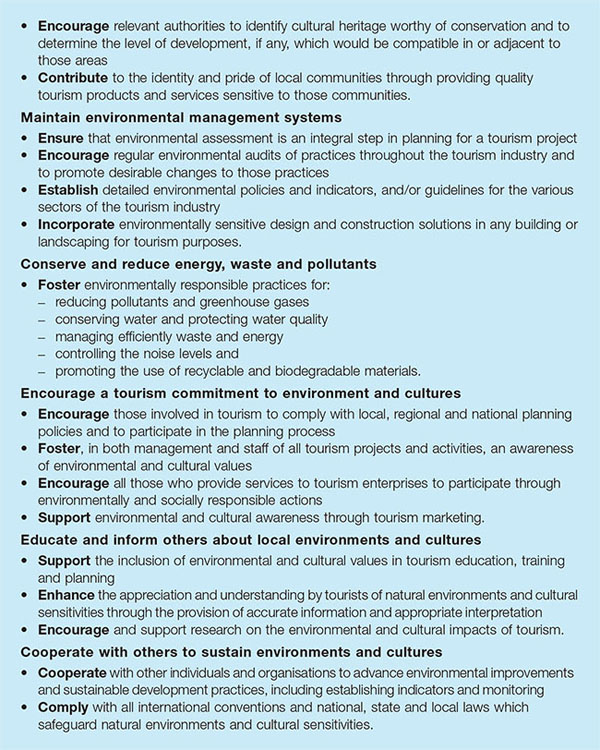

The APEC/PATA code (see figure 11.4) is representative. Members are urged to adopt measures related to environmental and social sustainability, many of which relate to the sustainability indicators provided in table 11.2. While acceptance of the code is supposed to indicate that the member is committed to achieving sustainable outcomes, the voluntary nature of the commitment has been much criticised. These codes of practice have also been criticised because of the vague and general nature of the clauses (which allegedly makes them hard to put into operation and too open to interpretation), the lack of timelines for attaining compliance and almost all of them being based on the principle of self-regulation. As such, they are vulnerable to abuse as greenwashing devices (Mason 2007).

333FIGURE 11.4 Pacific Asia Tourism Association code for environmentally responsible tourism

Source: PATA

However, there are also compelling arguments in favour of such codes:

The membership of organisations such as PATA (Pacific Asia Travel Association) and APEC (Asia–Pacific Economic Cooperation) is too diverse to accommodate detailed objectives and relevant indicators within a single code. The codes therefore provide the generic principles that everyone can agree with, and each type of member can then be referred to relevant best practice parameters as defined by a monitoring or other organisation. In this sense, the PATA principles overlap considerably with the UNWTO baseline issues listed in table 11.2.334

Codes are therefore a low-cost and low-risk gateway for moving gradually towards higher forms of sustainability-related quality control (Bendell & Font 2004).

Codes can be a powerful form of moral suasion in that uncomfortable questions and scrutiny may be directed at members who do not consciously pursue sustainability, given that members are assumed to have made such a commitment.

Reputable organisations such as PATA and APEC risk loss of credibility if members are seen to be code-noncompliant, and thus they have an incentive to encourage and tacitly enforce compliance.

Private corporations are more likely to cooperate with sustainability initiatives if they are not threatened or forced to accept obligatory objectives and deadlines through government regulation.

The self-regulation that is implicit or explicit in these codes is based on the premise that voluntary adherence to good practice within the industry itself will pre-empt governments from increasing their own regulations on the sector. Businesses, as a result, will be able to maintain greater control over their own operations if they show themselves to be good ‘corporate citizens’ by adhering to the spirit of applicable codes.

Ecolabels

Font (2001, p. 3) defines ecolabels as ‘methods [that] standardize the promotion of environmental claims by following compliance to set criteria, generally based on third party, impartial verification, usually by governments or non-profit organizations’. As such, they are considered to be a much stronger quality control mechanism than codes. Ecolabels are focused on the interrelated concepts of certification and accreditation. Certification involves an independent expert third party (i.e. other than the applicant or the governing ecolabel body), which investigates and confirms for an ecolabel body whether an applicant complies with that body’s specified sustainability standards or indicators. If so, then the ecolabel managers will formally certify the applicant. Accreditation, in contrast, is a process in which an overarching organisation evaluates the ecolabel itself and confers accreditation if it is assessed as being sufficiently rigorous and credible. In essence, the accrediting body certifies the ecolabel (Black & Crabtree 2007). A major challenge for the contemporary tourism industry is the absence of such an overarching accreditation body, although various peak organisations are currently collaborating to achieve this critical objective (see the case study at the end of this chapter).

Most of the approximately 100 tourism-related ecolabels are focused on a particular product or region (e.g. the Blue Flag ecolabel certifies only beaches). EC3 Global (www.ec3global.com) is an exception because it encompasses all tourism products and all regions, and in doing so is attempting to position itself as the world’s primary tourism ecolabel. Central to its multifaceted EarthCheck system is a graded membership structure consisting of 4 stages:

Benchmarking (Bronze) — based on presentation of a sustainability policy and completion of a benchmarking exercise that is assessed by EC3 Global

Certification (Silver) — requires compliance with relevant regulation and policies, and documentation of appropriate performance outcomes; includes an outside audit with onsite visit

Certification (Gold) — awarded to recognise five consecutive years of continuous silver certification

Certification (Platinum) — awarded to recognise ten years of continuous certification.

The actual number of tourism businesses participating in EarthCheck as of 2013 was very small as a proportion of the entire industry. One problem for EC3 Global and other ecolabels is that companies are reluctant to join until the certification or accreditation achieves greater visibility among consumers, but this is unlikely to occur without a higher level of participation from industry in the first place. In general, it does not appear yet as if tourism-related consumer purchasing is significantly influenced by whether such products are certified or not.

SUSTAINABILITY AND SMALL-SCALE TOURISM

SUSTAINABILITY AND SMALL-SCALE TOURISM

As suggested, much attention in the sustainable tourism literature has been devoted to small-scale tourism projects and destinations, on the assumption that such tourism is more likely to have positive environmental, economic and sociocultural impacts within a destination. The following discussion shows that the theoretical case for this assumption is sound, and there are indeed many examples of small-scale sustainable tourism. However, it should never be automatically assumed that the outcomes of small-scale tourism are always positive.

Alternative tourism

The cautionary platform identified the problems associated with mass tourism, but did not articulate more appropriate options in response. Alternative options appeared in the early 1980s in association with the adaptancy platform (see chapter 1). This new perspective held that because large-scale tourism was inherently problematic, small-scale alternatives were more desirable. The associated options, combined under the umbrella term of alternative tourism, were thus primarily conceived as alternatives to large-scale or mass tourism specifically, rather than in relation to other types of tourism or ‘alternative’ lifestyles.

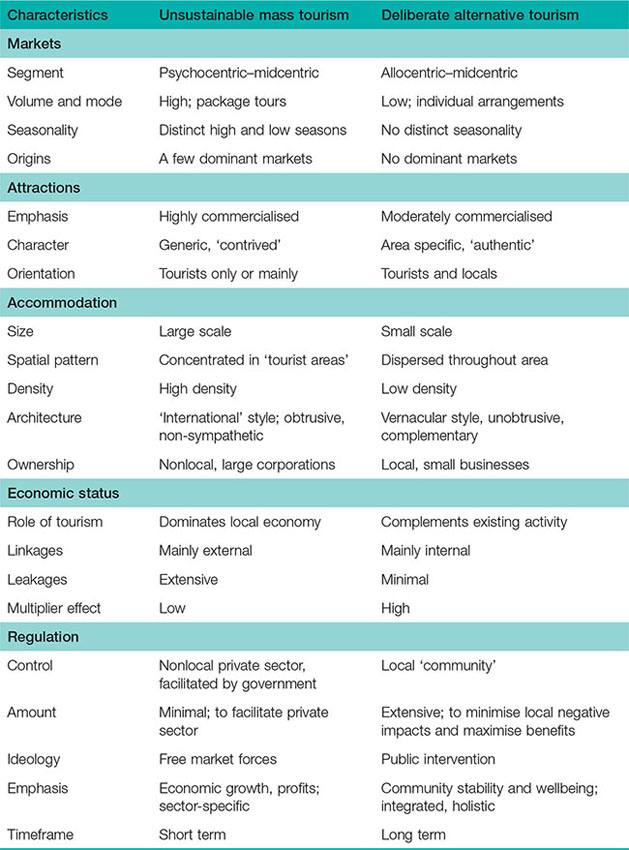

Figure 11.5 depicts mass tourism and alternative tourism as contrasting ideal types. These came to be widely perceived as models of ‘bad’ and ‘good’ tourism, respectively. Where mass tourism attractions are alleged to be ‘contrived’, alternative tourism attractions are ‘authentic’; where mass tourism supposedly fosters externally controlled, high-leakage operations, alternative tourism offers locally controlled, high-linkage opportunities and so on. It may be added that alternative tourism is expected to adhere to a strong (as opposed to weak) interpretation of sustainability, while mass tourism is seen by supporters of the adaptancy platform as following an unacceptably weak version.

Circumstantial and deliberate alternative tourism

In some cases, a destination’s affiliation with alternative tourism is superficial, the presence of the associated characteristics being simply a function of the fact that the destination is in the ‘exploration’ or ‘involvement’ stage of the Butler sequence (see chapter 10). This ‘unintentional’ variation can be referred to as circumstantial alternative tourism (CAT), meaning that this status merely reflects associations with the early circumstances of the resort cycle. In contrast, deliberate alternative tourism (DAT) occurs when a regulatory environment is present that ‘deliberately’ maintains the destination in that involvement-type state (Weaver 2000b). Returning to figure 11.5, the full set of alternative tourism characteristics in a destination is therefore indicative of the deliberate variation. If, however, the characteristics listed under 336‘regulation’ are absent, then this indicates the presence of the circumstantial variant. Note the similarities between the latter situation and the exploration/involvement stage characteristics listed in table 10.1.

The distinction between circumstantial and deliberate alternative tourism is critical, since a CAT destination has the potential (assuming that there is demand to visit this 337place) to evolve along an unsustainable path of development as per the Butler sequence (there being no preventative measures in place). In contrast, DAT reflects the influence of specific policy directives and controls (e.g. indicator thresholds and benchmark objectives that reflect a strong sustainability interpretation) that better ensure the maintenance of a sustainable, low-intensity tourism option based on keeping tourism activity below local carrying capacities (see figure 10.3(a)).

Manifestations

Since the 1980s, DAT-related products and opportunities have become increasingly diverse, but still account for only a very small proportion of all tourism activity despite ongoing growth in the green traveller market. Manifestations include:

cultural villages — Tourism for Discovery (Senegal)

homestays — Meet the People (Jamaica), Friendship Force (International)

feminist travel — Womantrek (United States)

indigenous tourism — Wanuskewin (Saskatchewan, Canada), Tiwi Tours, Camp Coorong (Australia)

older adult tourism — Elderhostel (international)

holiday farms — Worldwide Opportunities on Organic Farms (WWOOF) (international)

social awareness travel — Center for Global Education, Global Exchange, Plowshares Institute (all in the United States)

youth hostels

personal awareness tourism — ESALEN Institute (California)

religious tourism — monastery retreats

educational tourism — The Humanities Institute (United States)

volunteer activity — Habitat for Humanity, Global Volunteers (both in the United States)

guesthouses.

While these activities mostly occur in rural areas, urban DAT is also possible. One example is the urban cultural heritage tourism that is offered in the Soweto township of Johannesburg, South Africa (Rogerson 2004). Ecotourism, another primarily rural activity, first emerged in the 1980s as a nature-based form of alternative tourism. However, because it is now widely recognised as having mass as well as alternative manifestations, it is discussed separately in this chapter.

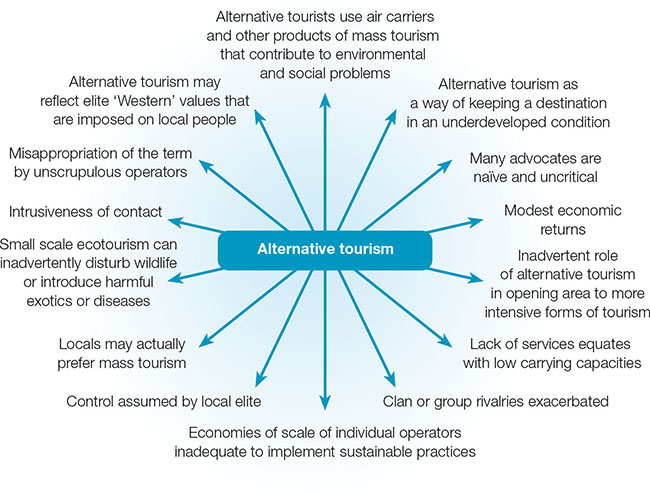

Critique of alternative tourism

Although a small-scale level of activity is implicit in alternative tourism, the absence of negative impacts cannot be assumed. Problems that can occur in association with this apparently benign form of tourism are depicted in figure 11.6. In conjunction with earlier comments made about the suitability of large-scale enterprises to implement sustainable practices, the opposite can be said about small operations. Operators of the latter often lack the resources or expertise to implement measures compatible with sustainable tourism, and are more immediately concerned about their very survival. Alternative tourists (e.g. voluntourists) themselves may cause sociocultural stress by being overly intrusive in their desire to experience ‘backstage’ lifestyles over a prolonged period of time, thereby increasing the potential for cross-cultural misunderstanding (see chapter 9). Similarly, they may unintentionally distress wildlife by their presence, or introduce harmful pathogens into sensitive natural 338backstage locales that have not been site-hardened or habituated to accommodate even small numbers of visitors. In both situations, these tourists may function as ‘explorers’, as per the Butler sequence, who inadvertently open the destination to less benign forms of tourism development. Despite their philosophical discomfort with mass tourism, alternative tourists also rely on mass tourism products, such as air transport, which contribute to unsustainability at a global level and reflect perhaps a certain amount of dishonesty in relation to their self-avowed ‘purity’ as a separate and more virtuous form of tourist.

A commonly cited criticism is the association of alternative tourism with elite ‘green’ value systems that place a high value on principles (such as the nonconsumption of natural resources) that may be incompatible with local hunting traditions or slash-and-burn farming techniques. Great pressure may be placed on locals by some NGOs to adopt the alternative tourism model, even though local residents in some cases might prefer a more intensive and larger-scale form of tourism that generates higher economic returns. Small-scale ecotourism is even seen as a way of keeping an area in an underdeveloped, primitive state for the benefit of a few wealthy ecotourists from the developed countries (Butcher 2006).

Where local residents are actually in control of an alternative tourism enterprise, most of this power may rest in the hands of the local elite, whose economic and social dominance in the community is thereby reinforced. Similarly, clan rivalries may be exacerbated if one group perceives that a rival group is gaining an advantage from a particular tourism initiative. Other problems include the continued naïvety of 339some advocates, who may be unwilling or unable to see its potential shortcomings, and the possibility that unscrupulous businesses may use the alternative tourism or ecotourism label as greenwashing to legitimise products that do not meet the appropriate criteria.

Finally, there is a broader argument that deliberate alternative tourism cannot possibly be the ‘answer’ to unsustainable mass tourism since it is not feasible to convert mass tourism resorts such as Australia’s Gold Coast and Spain’s Benidorm into alternative tourism destinations. This reinforces the contention that sustainability discourses must be focused on mass tourism. Indeed, it appears in many successful alternative tourism destinations that managers eagerly respond to growing demand by raising their carrying capacity threshold to accommodate more visitors, as per figure 10.3(b) (Weaver 2012b). Eventually, such places may in this way lose their identity as alternative tourism destinations. Similarly, the issue of whether backpacking is alternative or mass tourism is becoming increasingly contested as participation increases and related organisations and businesses become increasingly sophisticated (Larsen, Øgaard & Brun 2011).

ECOTOURISM

ECOTOURISM

Ecotourism is distinguished in three main ways from other types of tourism.

The natural environment, or some component thereof (e.g. noncaptive wildlife), is the focus of attraction, with associated cultural resources being a secondary attraction given that all ‘natural’ environments are actually modified to a greater or lesser extent by direct and indirect human activity.

Interactions with nature are motivated by a desire to appreciate or learn about the attraction. This contrasts with nature-based 3S or adventure tourism, where the natural environment serves as a convenient setting to fulfil some other motivation (e.g. sunbathing or thrill-seeking, respectively, in the two cases given here).

Every attempt must be made to operate in an environmentally, socioculturally and economically sustainable manner as per the triple bottom line. Unlike other types of tourism, the mandate to be sustainable is explicit, prompting Weaver (2006) to describe ecotourism as the ‘conscience of sustainable tourism’.

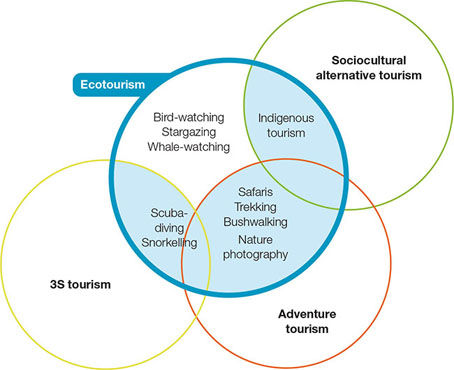

Within these parameters there are many activities that cluster under the ecotourism umbrella and extend this activity to once-inaccessible areas such as forest canopies and coral reefs through intermediating technology such as cableways and submarines. As depicted in figure 11.7, activities such as bird-watching, whale-watching and stargazing can be positioned entirely within ecotourism, while safaris, trekking and nature photography usually overlap with the nature-based components of adventure tourism. Similarly, scuba diving and snorkelling are affiliated with 3S tourism while tourism involving indigenous cultures is linked to sociocultural alternative tourism.

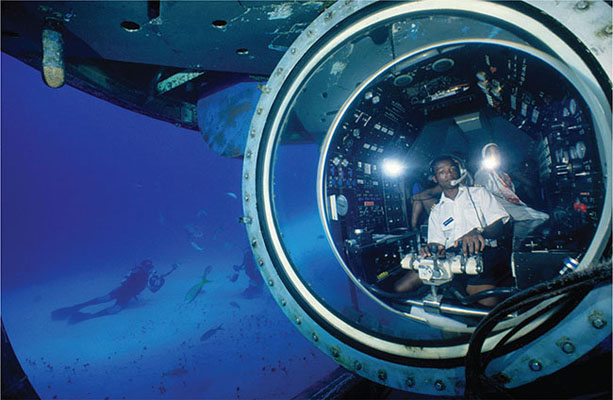

Opportunities for ecotourism have also been created beneath the ocean’s surface. In several South Pacific and Caribbean destinations, Atlantis Adventures operates submarines that can hold either 48 or 64 passengers (see figure 11.8). The non-polluting battery-powered vessels allow the passengers to view coral reefs and other marine phenomena more than 30 metres below the surface, with ample interpretation made available during the almost-two hour experience. Sophisticated sensors and other onboard technologies ensure that the submarines cause almost no disruption to the marine habitat, which includes artificial reefs specially constructed by the operators to relieve any potential stress on the natural environment.

340FIGURE 11.7 Major types of ecotourism activity

FIGURE 11.8 Up close and personal with an Atlantis submarine in the Caribbean

Soft and hard ecotourism

Ecotourism activities can be further classified as hard or soft, although as with mass and alternative tourism, these labels should be seen as two ends of a spectrum rather than as mutually exclusive categories (Weaver 2008). Hard ecotourism, as an ideal 341type, emphasises an intense, personal and prolonged encounter with nature. Associated trips are usually specialised (i.e. undertaken solely for ecotourism purposes) and take place within a wilderness setting or some other mainly undisturbed natural venue where access to services and facilities is virtually nonexistent. Participants are environmentalists who are highly committed to the principles of sustainability. This mode of ecotourism is most clearly aligned with alternative tourism and with a strong interpretation of sustainability. Indeed, it can be said that ecotourism first emerged in the early 1980s as a nature-based form of alternative tourism.

In contrast, soft ecotourism is characterised by short-term, mediated interactions with nature that are often just one component of a multipurpose tourism experience. Participants have some appreciation for the attraction and are open to learning more about sustainability and related issues, but the level of commitment to environmentalism, as a philosophy, is not as strong, indicating a higher incidence of veneer green consumer participation. Soft ecotourism takes place within less natural settings (e.g. park interpretation centre, scenic lookout, signed hiking trail, wildlife park) that provide a high level of services and facilities. This form of ecotourism usually occurs as a type of mass tourism informed by a weaker interpretation of sustainability. Nevertheless, with appropriate educational opportunities provided through effective product interpretation, there is evidence that soft ecotourism can instil positive environmental attitudes among participants (Coghlan & Kim 2012).

Magnitude

The magnitude one attributes to ecotourism depends on how much of the hard–soft spectrum and how many overlapping activities are embraced in the accepted definition. If one restricts ecotourism to the hard ideal type, then this sector is miniscule. A liberal definition that embraces an array of soft ecotourism products and hybrid activities such as scuba diving produces a much higher figure, probably in the 15–20 per cent range according to the UNWTO. Complicating such calculations is the multipurpose nature of most travel, wherein most participation in soft ecotourism occurs as one component of a multipurpose itinerary. The difficulties that arise in quantifying ecotourism and its relationships with other forms of tourism are illustrated by inbound tourism patterns in Kenya. The great majority of inbound visitors are conventional mass tourists who spend most of their time in the capital city (Nairobi) or in Indian Ocean beach resorts. However, many of these visitors select Kenya for their 3S holiday because of the diversionary opportunity to participate in a wildlife-watching safari excursion. The resultant soft ecotourism activity often occurs on a large scale within certain accessible protected areas, confirming ecotourism’s dominant status as a form of mass tourism.

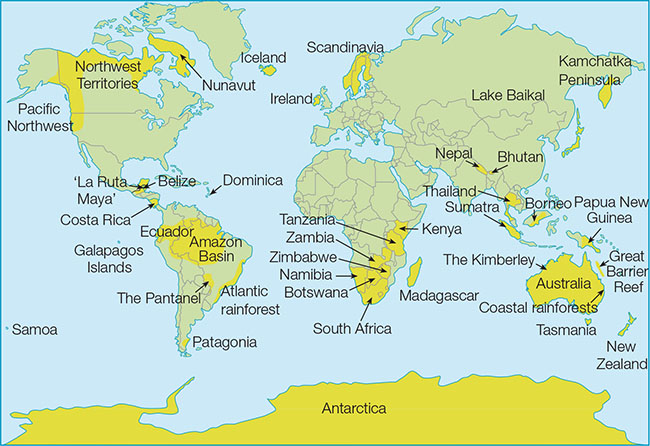

Location

Ecotourism destinations are usually associated with ‘natural’ or ‘relatively undisturbed’ settings. It is therefore not surprising that most ecotourism activity takes place within protected areas such as national parks, which provide both a relatively undisturbed setting and a DAT-like regulatory environment that restricts potentially harmful activities. Hard ecotourism tends to occur in the more remote regions of countries or individual parks, while soft ecotourism, as noted earlier, concentrates in the more accessible and site-hardened portions of parks that are located within a few hours drive from major cities or 3S resort areas (Weaver 2008). In the latter situations, it is typical for 34290–99 per cent of all tourist activity to occur within just 1–5 per cent of the park area. Given that such protected areas are expected to fulfil two potentially conflicting mandates — the preservation of local biodiversity and the accommodation of increasing visitor numbers — it is not surprising that situations arise and management decisions are taken that call into question the sustainability of ecotourism in such areas. While protected areas clearly do provide a potentially optimal venue for authentic, high-quality encounters with nature, there is no inherent reason for excluding modified environments such as reservoirs, farmland and even cities, that may also attract interesting birds or mammals. Ecotourism activity occurs in all parts of the world, but some regions and countries have attained a reputation as ecotourism destinations. Prominent among these are New Zealand and the Central American corridor extending from the Yucatan Peninsula and Belize to Costa Rica and Panama. Other important regions are the Amazon Basin, the ‘safari corridor’ from Kenya to South Africa, the Himalayas, the Pacific Northwest of North America, peripheral Europe, and South-East Asian destinations such as Thailand, Borneo and Sumatra (see figure 11.9). Australia has also acquired a reputation as an ecotourism destination, supported by what is widely regarded as the world’s most advanced ecotourism certification program and a very high number of attractive endemic (i.e. native) species of wildlife. Iconic ecotourism destinations include the Great Barrier Reef, Uluru, the Tasmanian Wilderness, Fraser Island, the Blue Mountains, Kakadu and Shark Bay.

FIGURE 11.9 Prominent world ecotourism destinations

DESTINATION SUSTAINABILITY

DESTINATION SUSTAINABILITY

Sustainability is achieved through the joint efforts of destination managers and individual businesses. Although constrained by vested interests associated with other sectors, destination governments and tourism authorities have access to mechanisms 343that facilitate their pursuit of sustainable tourism. Businesses must operate within these constraints; however, they often oppose them. Development standards, or legal restrictions that dictate the physical aspects of development, are one such destination response (Weaver 2006). Included in this category are:

density and height restrictions

setbacks (distances separating the outer edge of a development from another object, such as a footpath, floodplain or beach high water mark)

building standards (e.g. conformance of new construction to traditional architectural styles, minimum insulation requirements)

noise regulation

signage control (e.g. prohibitions on motorway billboards or shopfront advertising).

In addition, municipalities can pursue social sustainability by requiring resorts to provide reasonable pedestrian access between a public road and a public beach, as is often done in the Caribbean.

Zoning regulations, which demarcate specific areas for defined uses and development standards, are another important tool for destination planning and management, as are districting strategies that designate special urban or rural landscapes for focused management or planning that seeks to preserve the special historical, natural or cultural properties of these places. In the designated Chinatown district of Toronto, bilingual Chinese and English road signs and relaxed standards for the display of food and other commercial goods are both permitted in order to distinguish this neighbourhood as a Chinese–Canadian culture area and tourist attraction. Destination governments also have considerable scope for offering sustainability-related incentives to their constituent private sector tourism operators. One example is the Barbados Tourism Development Act (2002), which allows a 150 per cent tax deduction on expenses related to the pursuit of Green Globe hotel certification.

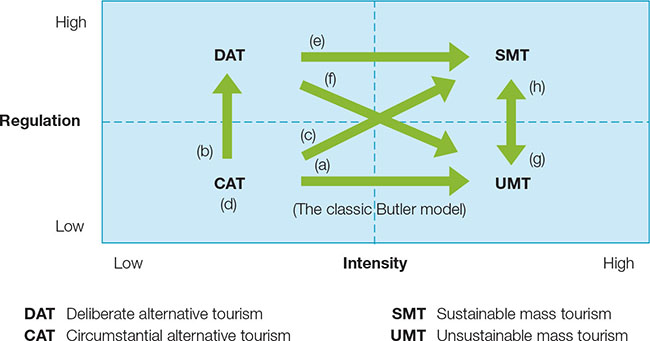

Extending the Butler sequence

Attempts to model the process of tourist destination development in the field of tourism studies have mostly focused on the Butler sequence and its pessimistic outcomes (see chapter 10). However, recent developments in the field of sustainable tourism suggest that a broader framework is necessary in order to encompass the full range of possible developmental scenarios. Such a framework is provided in figure 11.10. This broad context model of destination development scenarios consists of four basic tourism ideal types, based on the scale of the sector (small to large) and the amount of sustainability-related regulation that is present (Weaver 2000b).

In this model, small-scale destinations fall into either the CAT (i.e. little or no regulation) or DAT (extensive regulation) category. Similarly, large-scale destinations in theory are either unsustainable (= unsustainable mass tourism, or UMT) or sustainable, depending on the presence or absence of a suitable regulatory environment (= sustainable mass tourism, or SMT). As with other category-based models cited previously in this book (e.g. the attraction inventory in chapter 5 or the psychographic model in chapter 6), the graphed data fall along a continuum rather than into discrete categories. Thus, many different types of CAT destination will emerge, depending on the extent to which CAT-like criteria of scale and regulation are evident.

Possible paths of evolution

If only CAT destinations are taken into consideration initially, the broad context model offers four distinct possibilities for future development.

The Butler sequence is but one possible scenario, involving the movement of a destination from CAT to UMT (a). The progression in this scenario is from an unregulated ‘involvement’ stage to an unregulated and unsustainable ‘consolidation’ stage or beyond.

Alternatively, a CAT destination can move to DAT through the implementation of the regulatory environment required to maintain the characteristics of alternative tourism (b). The Caribbean island of Dominica and the Himalayan kingdom of Bhutan followed this trajectory before 2000.

A CAT-to-SMT sequence can occur when a mass tourism industry is superimposed over an undeveloped region in a highly regulated way (c) using a growth pole strategy.

A CAT destination where there is the absence of any evolution at all (d). This scenario assumes that not all CAT destinations will attract sufficient levels of demand to stimulate any further tourism development. For example, most of outback Australia is not likely within any foreseeable timeframe to move beyond exploration- or involvement-stage dynamics, given the absence of push or pull factors that would draw these areas into the mass tourism system. One implication is the lack of need in such cases to allocate resources towards the establishment of DAT. Instead, resources should be directed to identifying and managing locations where the potential for intensification to occur is higher, such as coastal and alpine destinations.

Moving beyond CAT, other depicted scenarios include the movement from DAT to either SMT (e) or UMT (f). The former situation occurs when the destination is able and wants to increase its carrying capacity thresholds to accommodate higher visitation levels. Both Dominica and Bhutan now appear to be following this strategy (Weaver 2012b). A DAT destination, however, can also move towards UMT if the appropriate adjustments to carrying capacity are not made, or cannot be made. This is 345illustrated by national parks such as Amboseli (Kenya), where visitation levels during the 1970s far outpaced the capacity of park managers to cope with the resultant stresses (Weaver 1998).

Finally, SMT can be transformed into UMT as a result of similar dynamics (g), while the opposite is also possible. As described in chapter 10, Benidorm, on the Spanish pleasure periphery island of Mallorca, is an example of a previously unsustainable tourism-intensive destination that is making significant progress towards the attainment of sustainability (h).

346

CHAPTER REVIEW

In response to increasing contradictions and anomalies in the dominant Western environmental paradigm, our society appears to be moving towards a more ecocentric green paradigm. This shift has seen the concept of sustainable development become the focus of contemporary tourism sector management, with weak and strong interpretations possible, depending on whether a particular destination consists mainly of undeveloped natural habitat or heavily modified landscapes, respectively. These developments all suggest the emergence of a synthesis between the dominant Western environmental paradigm and the green paradigm. In any case, the identification and monitoring of indicators at the destination and operations level is essential if sustainable tourism (however defined) is to be achieved, but associated procedures are marred by our basic lack of understanding about the complexities of tourism systems, and other problems. Nevertheless, the concept is still worth pursuing, since not to do so is to virtually ensure unsustainable outcomes.

The mass tourism industry, long notorious for following an unsustainable path of development, is now pursuing sustainable tourism more seriously because of the rapid growth in green consumerism, the potential profitability of sustainability-related measures and self-enlightened ethical considerations. It is assisted in this effort by its own economies of scale. However, the penetration of sustainability-related practices within the conventional tourism industry does not appear to extend much beyond the establishment of facilitating structures within various sectors and the leadership of a few corporate innovators, suggesting a shallow level of adherence that complements the dominance of ‘veneer’ environmentalists within society at large. Practices such as recycling and linen reuse programs indicate paradigm nudge rather than paradigm shift because they can be easily accommodated within the precepts of the dominant capitalist ideology. The rudimentary state of specialised quality control mechanisms supports this contention. Codes of practice, for example, are abundant but controversial; as high-profile certification-focused global ecolabels have attracted only minimal participation to date, and there is no overarching accreditation body established to ‘police’ such tourism-related ecolabels.

Many researchers, therefore, remain sceptical about the motives of the conventional mass tourism industry, and a great amount of attention is still being given to the concept of alternative tourism as a presumably more benign alternative to mass tourism. Even so, alternative tourism itself has been criticised for its intrusiveness into backstage spaces, its limitations of scale, and its potential for opening destinations to less benign forms of tourism. Ecotourism was initially conceived in the 1980s as a nature-based form of alternative tourism but has since been widely acknowledged as having both a hard (mainly alternative tourism/strong sustainability) and soft (mainly mass tourism/weak sustainability) manifestation. Protected areas remain the most popular ecotourism venue, though more attention is being paid to the suitability of less ecologically vulnerable urban and other highly modified spaces.

Tourist destinations, as opposed to businesses, present distinctive sustainability-related challenges such as the presence of diverse public and private constituencies as well as a usually dominant nontourism sector. Nevertheless, destination governments possess tools such as the establishment of development standards and zoning regulations that, with the cooperation of local businesses, aid the pursuit of sustainable tourism. They are assisted in this pursuit by the broad context model of destination development scenarios, which depicts the range of potential tourism options, of which 347the Butler scenario (CAT-to-UMT) is just one. Deliberate alternative tourism (DAT) and sustainable mass tourism (SMT) are the two desirable scenarios, depending on whether a weak or strong interpretation of sustainability is warranted.

SUMMARY OF KEY TERMS

SUMMARY OF KEY TERMS

Accreditation the process by which the ecolabel is determined by an overarching organisation to meet specified standards of quality and credibility

Alternative tourism the major contribution of the adaptancy platform, alternative tourism as an ideal type is characterised by its contrast with mass tourism

Avalanche effect the process whereby a small incremental change in a system triggers a disproportionate and usually unexpected response

Aviation biofuel renewable plant or animal-based aircraft fuels; these are being more commonly used in commercial aviation, and mostly at present to supplement conventional fossil fuel loads

Benchmark an indicator value, often based on some past desirable state, against which subsequent change in that indicator can be gauged