CHAPTER

3

THE COMMON BLINDSPOTS HOLDING LEADERS BACK

Successful individuals who sometimes stumble often do so because they have no one who can protect them from themselves. Lance Armstrong is a case in point.1 The seven-time winner of the Tour de France is a cancer survivor who inspired millions suffering from the disease and created a foundation to help those in need. He also used performance-enhancing drugs and brazenly lied about doing so for over a decade. Armstrong now faces widespread disgrace—stripped of his Tour de France titles, forced out of the charitable foundation he created, dropped by his corporate sponsors, and given a lifetime ban from the sport he loved. His is a cautionary tale of the risks faced by those who strive for greatness and, in so doing, lose the ability to accurately see themselves and the consequences of their actions. Armstrong's story also teaches us the risk that leaders take when they surround themselves with those who tell them only what they want to hear.

Armstrong viewed his deceptions as minor failings in relation to the good he was doing by inspiring cancer victims through his story of recovery and achievement. He was also proud of the important services offered to survivors by his Livestrong Foundation. He didn't see himself as cheating but simply “leveling the playing field” in a highly competitive sport where the vast majority of riders were doping. He was cocky and relentless—methodical in pursuing what he wanted in every aspect of his life. Working to avoid detection for using illegal drugs was simply one more challenge for a man who had proven his ability to be the master of his own fate. This became part of what he described as his “narrative,” which he felt he needed to sustain for a host of personal, professional, and financial reasons. He was willing to do what was necessary, including ruining his detractors, to protect his image and the brand he had created. He described those who were skeptical of his achievements as people who “don't believe in miracles.”

A number of people knew about Armstrong's doping (fellow riders, assistants, doctors, friends, spouses, and most likely team managers). Armstrong still believed, in an age of constant media scrutiny, that they would remain silent or that he could refute any damaging information they might reveal. His entourage included those with an unquestioning loyalty to him and his pursuit of greatness. Armstrong's need to have people around him to provide psychological support is not surprising. High achievers often want people around them who believe in them and, in so doing, sustain their motivation and confidence. Armstrong, however, took this need to an extreme level. Members of his team were required to reinforce his narrative even if it meant engaging in or condoning illegal acts. Those who didn't play by his rules or found fault with him were banished from his team and, in some cases, the racing community. As a result, he had no one who would forcefully challenge him—no manager, coach, agent, lawyer, or spouse who was strong enough to influence him—strong enough to say, “You can't do that.”

Armstrong, looking back after his legacy unraveled, believes that he was consumed by what he calls “the ride”—both in the desire to keeping winning and in the worldwide fame that followed. While he now takes accountability for his actions, Armstrong suggests that he is not the only one to be seduced by the potentially corrupting influence of power and wealth. On his downfall, he noted:

My ruthless desire to win at all costs served me well on the bike but … is a flaw. That desire, that attitude, that arrogance. … All the fault and all the blame … falls on me. But behind that picture and behind that story is momentum. Whether it's fans or whether it's the media, it just gets going. And I lost myself in all of that. I'm sure there would be other people that couldn't handle it, but I certainly couldn't handle it, and I was used to controlling everything in my life.2

Lance Armstrong is now experiencing the backlash of a public that feels betrayed after his decade of deceit. However, the factors that drove him to be the best in his sport are the same qualities that drove him to distort reality and rationalize his fraudulent behavior. In other words, the “good” and the “bad” Armstrong arose from the same source. This doesn't absolve him of his misdeeds, or suggest that all high achievers succumb to unethical behavior. It does suggest that reaching his level of accomplishment is fraught with risks and requires awareness of the traps that await those on that path. There is a well-known study that asked elite athletes if they would take a drug that guaranteed them a gold medal in the Olympics but would kill them within five years. More than 50 percent of these world-class athletes answered yes. When nonathletes were asked the same question, less than 1 percent answered yes.3 High achievers, in sports and beyond, are frequently driven by a singular focus and an associated lack of perspective—which can be their defining strength and most significant weakness. Lance Armstrong is clearly an extreme case, and I am not suggesting that most achievers act in an analogous manner. Great achievers, however, carry with them the potential for equally great acts of self-delusion—for having weaknesses and threats that they don't see or that they rationalize as being unimportant in comparison to the goals they are pursuing. Armstrong's story illustrates the danger of getting caught up in “the ride” and surrounding yourself with a cadre of people who either don't see or don't challenge your self-destructive thinking and behavior.

BLINDSPOTS THAT CAN DERAIL YOU

This chapter focuses on the common blindspots I have seen in my work with leaders. In total, I highlight twenty blindspots worthy of your attention as you examine your own beliefs and behaviors. Several caveats are in order before we get to common areas of blindness holding leaders back. First, I am seeking to identify not the most common leader weaknesses, but rather those areas in which leaders lack awareness of their weaknesses. In these cases, what the leader believes is different from the reality of what is occurring. Second, the importance of each type of blindspot varies in relation to the company in which a leader operates. One firm's culture may penalize certain blindspots more than others. Acting in an arrogant manner can be a career derailer in some firms, while in other firms it is viewed as a necessary leadership attribute. Third, the totality of a leader's capabilities affects the impact of particular blindspots. That is, blindspots are relative to a leader's overall strengths and weaknesses. Some leaders get the big things right and, in so doing, may mitigate the impact of their leadership flaws, which may look negligible in comparison. On the other extreme, a leader who is already facing criticism will most likely be viewed more harshly for certain blindspots because they become one more reason to doubt his or her ability to lead. Fourth, being aware of a blindspot is no guarantee of success. Many factors influence a leader's success and failure, with self-awareness being but one of the many necessary attributes. A leader who lacks necessary skills will not succeed even if he or she is the most self-aware person you know. Finally, you may have only one or two of the following blindspots, or none at all. You also may have blindspots that I have not mentioned but deserve further examination. My intent in this chapter is to provoke your thinking—you will need to judge whether the following apply to you.

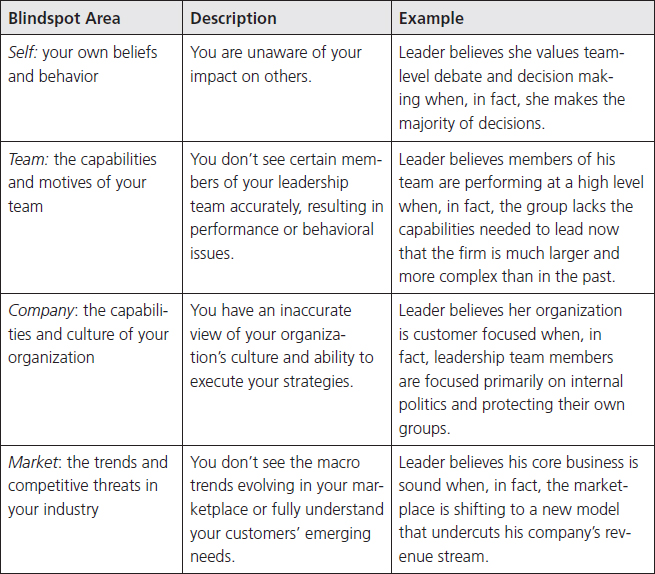

As mentioned in Chapter Two, blindspots occur in four areas, as shown in the “Types of Blindness” table. One benefit of looking at blindspots as operating on multiple levels is that it helps you avoid the tendency to think of them only in terms of a leader's self-concept and impact on others. While this is an important area, the other areas (team, company, and markets) are also important and, in some situations, more critical to the success of a leader and his or her firm. Consider the leadership team members who are concerned that their leader is too blunt, even punishing, in how he deals with them and the next level of management in their company. The leader doesn't see that his style is intimidating people and the consequences in their reluctance to be open with him. While this is indeed a blindspot, it pales in importance when compared to the larger challenge facing the company in regard to its expansion into global markets. In particular, the firm's investment in these markets is being mismanaged because the members of the leadership group have no experience in foreign markets. As a team, however, they incorrectly believe they have the background and knowledge needed to make high-quality decisions in this area. That is the blindspot which demands a leader's attention in that company.

Types of Blindness

Twenty Common Leadership Blindspots

Self

1. Overestimating your strategic capabilities

2. Valuing being right over being effective

3. Failing to balance the what with the how

4. Not seeing your impact on others

5. Believing the rules don't apply to you

6. Thinking the present is the past

Team

7. Failing to focus on the vital few

8. Taking for granted your team model

9. Overrating the talent on your team

10. Avoiding the tough conversations

11. Trusting the wrong individuals

12. Not developing real successors

Company

13. Failing to capture hearts and minds

14. Losing touch with your shop floor

15. Treating information and opinion as fact

16. Misreading the political landscape

17. Putting personal ambition before the company

Markets

18. Clinging to the status quo

19. Underestimating your competitors

20. Being overly optimistic

BLINDSPOTS ABOUT YOURSELF

Blindspot 1: Overestimating Your Strategic Capabilities

Leader Belief

I have developed an effective strategy for driving our future growth. We understand the shifts occurring in our market and have made the tough choices by investing in the areas that have the greatest growth potential. The strategy is supported by my leadership team and clearly communicated within our organization.

Common Reality

Many leaders are better at managing operations than thinking strategically. Even more problematic is that they don't see this gap, which, in some cases, becomes evident only when they are promoted into more senior roles that put a premium on identifying and acting on new growth opportunities. They spend most of their time on operational issues, resolving near-term challenges. In more extreme cases, leaders get lost in the operational details and do not have a broad strategic view for the business.

Illustrative Case

The leader of a sales group in a large pharmaceutical firm had built a highly effective sales force. Over the years, he increased the size of the group and trained his team to be highly effective in their interactions with physicians. The issue was that the industry was changing, with access to physicians becoming more restrictive. His company was also facing pressure on its margins due to price controls. As a result, new approaches to selling were needed, including an innovative use of technology to reach and influence those making buying decisions. The problem was that the sales leader knew only a traditional approach to selling—which he had perfected over decades of customer experience. He talked about the need for new strategies but managed primarily with the goal of achieving his group's near-term financial targets.

Blindspot 2: Valuing Being Right over Being Effective

Leader Belief

I am open to information and recommendations from a variety of sources, even when others hold views that are contrary to what I believe. I surface and listen to a range of viewpoints, working in a highly collaborative manner with members of my leadership team and peers. While I am confident in my own leadership judgment, I believe in the merits of making team decisions when necessary in dealing with the critical challenges we face.

The leader believes he or she is smarter than others and discounts their recommendations on issues both great and small. When given a choice between being right and being effective, the leader's insistence is on being right. He or she regularly interrupts people and focuses on finding fault in what they are proposing. Focused on action, the leader doesn't fully explore options or risks before moving forward. The leader is also defensive when others surface concerns or even question his or her plan of action. As a result, team members will not challenge the leader on important issues. Their attitude is, “Why bother voicing my views, and risk being wrong or alienating my boss, when it will have no impact on the outcome?”

Illustrative Case

The CEO of a technology firm wanted to pursue a new opportunity in an area in which his firm had not excelled in the past. To that end, he struck a deal with a small start-up company with the intent of leveraging its technology to create a new and innovative product. Members of the CEO's team advised against the acquisition because the technology was still evolving and there were questions regarding the ability of the acquired firm to take the product to the next level of development. The CEO didn't have a great deal of respect for his own team members, most of whom were his peers before he was promoted to CEO. They were, to his mind, competent but not on par with himself in regard to intellect or strategic vision. He pushed forward with the acquisition. All the team members knew that they now needed to fall in line. They concealed their ongoing reservations about the acquisition and worked hard to make it a success. However, their initial concerns proved to be correct, as the technology failed to develop in a manner that would meet customer needs. The CEO, eager to show results, wouldn't revise his launch timeline to allow for necessary improvements. The product was launched but failed to meet sales projections. After three years of effort, and significant financial losses, the product was killed. It was a black eye for the CEO and his company, suggesting to the firm's board and Wall Street that the firm would have difficulty growing beyond its base business.

Blindspot 3: Failing to Balance the What with the How

Leader Belief

I place great emphasis on delivering results. I also insist, however, that we operate in the right way.4 I believe how we go about our work is as important as what we achieve. Our core values and practices are central to our identity as a company, and I don't tolerate people who operate outside the lines.

Common Reality

There are two types of blindspots in this area. The first error occurs when a leader places excessive emphasis on results and doesn't see that he or she is creating a win-at-all-costs mentality within the organization. This view can become so extreme that the leader neglects, or turns a blind eye to, the means people use to deliver results. In some cases, this results in ethical violations or destructive behaviors such as people competing with each other to achieve individual goals in a manner that harms the larger enterprise. The second, and opposite, type of error occurs when a leader focuses primarily on the way people work together but doesn't place enough emphasis on delivering results. Not enough emphasis is placed on delivering the hard results that customers and shareholders expect.

Illustrative Cases

What over how. The leader of a regional commercial group was known for delivering on his financial targets, which was important because his region was the largest revenue producer in his firm. He delivered for three years in a row and then began to struggle. The pattern in the group was to “fight fires” and find a way to deliver on the numbers at the end of each quarter. The leader focused almost exclusively on the sales numbers and put constant pressure on his people to deliver on quarterly targets. He would become angry when they fell short and berate underperformers in team meetings and in private. His view was, “They don't get what I am telling them, and I end up needing to push them and their groups to deliver.” Yet, he would not make changes in the staffing of his team to address what he saw as shortcomings in leadership. Instead, he had a habit of verbally berating people for poor performance and then coming back later and apologizing to them. The problem was that the business had grown in size and complexity, and gaps in the talent on his team were increasingly a problem. His group's management processes were also in need of improvement in crucial areas (such as financial reporting and analysis). The leader didn't see these more systemic issues and simply believed that his people needed to “up their game.” He became more and more punishing as the results continued to decline.

How over what. The leader of an advertising group had been successful because of his ability to attract and retain top talent. He also took pride in practicing what he viewed as a collaborative approach that fully leveraged the talent on his team. He looked for consensus whenever possible and took the time needed to reach a group decision. The downside of his approach was that decisions were taking too long in some cases and team members were becoming frustrated with the amount of debate needed to move forward. His leadership style also had the effect of promoting compromise solutions, in order to gain agreement among members on contentious issues. This did not necessarily produce the best solutions. For example, the group developed a marketing and branding campaign for its agency that was developed from input from everyone on the group's leadership team. The result was a product that everyone supported but that lacked the edge needed to be effective.

Blindspot 4: Not Seeing Your Impact on Others

Leader Belief

I understand how my behavior is viewed by others. As a result, there are few if any surprises when people give me feedback. In many cases, I have taken their input and modified my behavior as needed to be more effective. When I don't change, it is because my approach is what the business needs (even when people may not like it).

Common Reality

The leader has an imperfect, even flawed, understanding of his or her impact on others.5 This oversight is often combined with a tendency to think that others are like the leader (in what motivates them, how they make decisions, how they respond to adversity, and so forth).

Illustrative Case

A leader was newly promoted to the senior role in the finance group of a large manufacturing company. He was smart and able to get things done. However, some of his peers viewed him as dishevelled and prone to making rambling comments in team meetings. His peers were concerned that he now represented the company in important forums such as earnings calls and board presentations. Some questioned if he had the gravitas needed to be an effective chief financial officer. He was frustrated when the issue was brought to his attention. He prided himself on putting “substance over style” and thought the feedback said more about others’ values than what was needed in his role. He noted, “We have too many people in this company who care more about how they look than how they perform. I am proud to say that I am not one of them.” I suggested that he solicit additional input from people he respected. He decided to talk with an informal mentor, an individual he knew from the past and who had become the CFO in another company. His mentor told him that his role required that he influence people who didn't know him and that they would judge him on how he presented himself and his ideas.

Blindspot 5: Believing the Rules Don't Apply to You

Leader Belief

I would never do anything that would damage my reputation or that of our company. The rewards and perks I receive are fair, given the central role I have played in growing the company. In fact, I hold myself to a higher standard than others.

Common Reality

Some leaders let the power and status that come with their position result in a sense of entitlement. As a result, they bend or break the rules. In more extreme cases, they violate company norms (extravagant expenditures …), policies (falsifying expense reports …), or even laws (trading stock on inside information …).

Illustrative Case

John Thain, when he was CEO of Merrill Lynch, was among the highest-paid executives in the world. The year before his company was bought by Bank of America, he made $83 million in compensation. Thain also had a reputation for spending lavishly on company perks. In one highly visible example, he spent $1.2 million of corporate funds to renovate his office, including a reported $131,000 for area rugs, $68,000 for an antique credenza, $87,000 for two guest chairs, $35,115 for a gold-plated commode, and $1,100 for a wastebasket.6 This was done when Merrill had just entered a difficult financial period, posting multibillion-dollar losses. Thain had not broken company policy but realized his actions looked extravagant given the financial challenges facing his company and the country in total. He subsequently apologized for his lapse of judgment and reimbursed the company in full for the costs. He compounded his problems by authorizing huge bonuses for his team just prior to the deal with Bank of America being finalized. Again, there was public outcry about the money the government was infusing into failing financial institutions at the same time when some the industry's leaders were acting in ways that were viewed by most as excessively greedy.

Blindspot 6: Thinking the Present Is the Past

Leader Belief

I am confident in my abilities, given my past successes. I also learn from my failures and those of others. As a result, I am able to assess new situations and determine what is needed, modifying my approach to the challenges we face. I realize that what worked for me earlier in my career may not work as I encounter new challenges.

Common Reality

New challenges are viewed as being similar to past challenges and addressed as such, applying proven methods and behaviors in a manner that does not always fit the need. In particular, the leader is unable to identify the situations that require a new approach, one that breaks from his or her past practices. In more extreme cases, emerging threats are not recognized because they don't fit the way a leader thinks or the approaches he or she favors. The leader's view is, “I have risen to my current position using an approach that works for me. My track record is one of delivering results. The company thinks I have the right stuff or I wouldn't have been promoted. Why should I change now?”

Illustrative Case

A new CEO moved into the role focusing on financial results and operational details, just as he had earlier in his career. He didn't believe that he needed to work in a more expansive leadership manner, particularly in regard to building relationships with the firm's external stakeholders (regulators, financial analysts, industry groups, media, and so forth). Instead of seeing himself as a CEO, he continued to operate like a chief operating officer, but now with more authority. His implicit COO leadership model, based on what had worked for him in the past, influenced the areas in which he spent his time, the priorities he set for the organization, the metrics he used to assess performance, and the solutions being advanced.

BLINDSPOTS ABOUT YOUR TEAM

Blindspot 7: Failing to Focus on the Vital Few

Leader Belief

In my leadership team, we spend the majority of our time on the key issues and risks facing our organization—the vital few issues that will determine our future success or failure. We take on these tough issues, and we deal with conflict in an open and constructive manner to reach the best solutions.

Common Reality

The majority of the leadership team's time is spent on less important issues that are typically administrative or operational. The most critical issues facing the team are not on the team's agenda or are addressed in a superficial manner. The leader's team is spread too thin to do the work needed on the truly critical issues. The team also backs away from conflict and avoids making risky decisions. As a result, the team meetings are often polite affairs, with the toughest issues being sidestepped (or dealt with only outside of meetings).

Illustrative Case

A leadership team met once a month for an all-day session that covered a range of topics from progress on new product introductions to softer issues such as the results on the firm's employee climate survey. Each month, the leader would ask for input on what should be on the agenda, but few would respond. Those who did would propose reviewing areas related to initiatives originating in their own groups. The communications group, for instance, wanted to review a new employee website they were building. There were no standing items on the agenda, such as a review of the firm's progress on its key imperatives. In addition, there was a lack of clarity regarding the purpose of each agenda topic (for instance, information sharing, problem solving, or decision making). The result was a meeting that covered too many topics and did not allow time for in-depth discussion on the vital few issues.

Blindspot 8: Taking for Granted Your Team Model

Leader Belief

The approach I use with my team fits the needs of my organization. I seek to take advantage of the strengths of each individual and the team in total. Overall, we operate in an effective manner and add real value to the business.

Common Reality

The leader uses an approach to the team that fits his or her personal preferences—independent of what the business needs or what the team needs. This results in not fully understanding or managing the downsides of the team model in use. For example, a leader likes being the hub of all decision making and thus works on a one-off basis with each team member. Or the leader wants to retain decision-making authority but doesn't understand that this is creating a bottleneck in the organization. In these situations, the team is a team in name only in that it has no common tasks to perform. It is a collection of people who work individually to provide input for the senior leader's decision-making process.

Illustrative Case

A leader wanted to be inclusive in her management approach. As a result, she had twenty people in her leadership group (which included all her direct reports and the functional leaders who reported in through their own lines of authority but provided support to her group). Her team would come together once a month to review key issues and opportunities. However, it was almost impossible to make a decision with such a large number of people around the table. Meetings turned into a series of debates with few clear outcomes. When pushed to modify the design of her team, she resisted because she liked people feeling engaged and involved in key decisions. Her view was, “I want everyone reporting to me to be involved in our decision making. I know it can be inefficient but the benefit is greater than the cost.” As a result, her team meetings were largely unproductive and resulted in frustrating many of the most talented team members, who saw the need for a more productive approach.

Blindspot 9: Overrating the Talent on Your Team

Leader Belief

My team is strong and deserves credit for bringing the company to where it is today. I know each member well and understand how he or she can best contribute to the business, including his or her strengths and weaknesses. We work well together as a group and are loyal to each other. In total, I have the talent I need to take us to the next level as a firm.

Common Reality

The leader overestimates the strength of his or her team, including particular members who are protected by the leader. The team doesn't have the talent needed to compete given the challenges facing the firm today and in the future. In addition, little effort is made to actively develop those whose capabilities are deficient.

Illustrative Case

A business unit leader had not delivered on his financial targets for several years. This leader was frustrated with his team but believed they could be coached to higher levels of performance. The reality was that several members of his team had strong technical skills but lacked the leadership capabilities needed to deliver and grow their businesses. The leader refused to see this and instead sought to provide the necessary coaching to those in need. He believed he could develop his underperforming managers when others had failed. His coaching had some impact, but the problems with two key team members persisted and the firm's performance didn't improve.

Blindspot 10: Avoiding the Tough Conversations

Leader Belief

I monitor the performance of each group within my organization as well as that of individual team members. Those who are underperforming are given honest feedback as well as necessary support to address gaps in their performance. I am fair with people but tough if they underperform.

Common Reality

The leader doesn't like dealing with people or organizational issues. Difficult conversations are avoided, or the message is delivered in such a subtle manner that its impact is minimized. The underperforming members of the team are retained in positions for which they are a poor fit. The higher-performing team members are frustrated by being forced to carry those who are not delivering on their commitments.

Illustrative Case

The head of a business unit in a biotech consulting group was frustrated because her unit had performed above requirements and yet the company, in total, had underperformed. The issue was that the head of another, much larger, business unit had consistently failed to meet his performance targets. She believed the CEO of the firm favored the head of the underperforming unit, as both were founding members of the company. The head of the high-performing business unit, frustrated with a culture that didn't hold everyone equally accountable, decided to accept an offer from a competitor. The CEO met with the departing executive to discuss her reasons for moving on. She indicated that she was frustrated by the firm's unwillingness to deal with chronic underperformance. She told him that the final blow came when she was asked to cut the size of her group to make up for the failures of others.

Blindspot 11: Trusting the Wrong Individuals

Leader Belief

I am a good judge of people and can accurately assess others’ capabilities and motives. I am also open to input if my judgments about others are wrong, and will change my views as needed when presented with new information.

Common Reality

The leader creates an inner circle of confidants, a few of whom may not be operating in an open and trustworthy manner with their peers. Their primary interest is in sustaining their own power by protecting their access to and influence over the senior leader. The leader is not open to negative feedback about those in his or her inner circle, and supports them even when they are damaging his or her credibility.

Illustrative Case

A new executive vice president of an insurance company had made a number of changes in her leadership team. In particular, she had appointed a new head of human resources for her group. The HR leader soon alienated a number of the key members of the leadership team. He was seen as being divisive and untrustworthy in how he used information to buttress his own status in the firm and gain influence over the EVP. More generally, he saw his mandate as one of upgrading the talent in the organization and soon became the power behind the throne in forcing personnel changes within the leadership team and at the next level of management. A spirit of distrust permeated the leadership team. The executive vice president, however, saw the HR leader as doing the tough work that needed to be done and viewed him as her closest confidant. By the time the EVP realized her mistake, it was too late. The CEO intervened and removed her for a number of failures, one of which was the damage she and her HR leader had done to the culture of the group she was leading.

Blindspot 12: Not Developing Real Successors

Leader Belief

There are a number of potential successors for my position and the other key roles at the top of the company. I am working hard to develop the most talented individuals in my team and at the next level of management. A significant portion of my time is spent ensuring that we have the talent we need to compete both today and in the future.

Common Reality

The leader has only a superficial commitment to identifying and developing potential successors for the top position. The succession pool is weak across the board, including a lack of talent in key commercial and functional areas. Little effort is made to identify or take risks on high-potential people and groom them for future positions. Key developmental positions are filled by those who are competent but lack the raw talent needed to move up to higher levels of authority.

Illustrative Case

The succession race at an information technology firm was among three executives who each believed he or she should move into the top position when the current CEO retired. Each, however, was flawed in a different way. One of the candidates had recently come into the industry and lacked a deep understanding of market dynamics. The second was indecisive and had difficulty making tough decisions in a timely manner. The third was lacking in strategic thinking capabilities. In total, the flaws in each were significant, and yet the CEO and board believed they had the talent pool they needed. No effort was made to identify potential successors at the next level or groom them as potential dark horse candidates. There was also no effort made to look at external candidates and compare them to the three internal executives in the succession race.

BLINDSPOTS ABOUT YOUR COMPANY

Blindspot 13: Failing to Capture Hearts and Minds

Leader Belief

I have communicated a clear direction and set of priorities for my firm. People are excited, and we have the support of those at the lower levels who must execute our plan. I have clarified my expectations and effectively communicated our targets and plan of action.

Common Reality

People in the organization, and even some members of a leader's own team, are unclear about the direction of the firm. For example, they can't name the top three priorities of the company. The leader fails to understand the need to actively sell his or her plans within the company and to other key stakeholders such as board members.

Illustrative Case

A business technology leader developed a bold new strategy for his region in Asia, working with a handful of people who were closest to him over a period of six months. He then communicated the strategy in a kickoff meeting for his regional functional staff, and assumed that his team would then take ownership for cascading the strategy within their respective countries. Six months later, there was widespread confusion about the strategy and how it would be executed. On being told of the confusion, the leader was frustrated with his team and couldn't comprehend why people didn't understand the direction he had set. A second problem was that some of his peers in headquarters didn't have a grasp of what he was implementing in his region because he didn't take time to update them on his strategy. One of his key peers, someone who provided support for regional initiatives, noted, “I am embarrassed to say but I don't know the details of his strategic plan. I have seen it discussed only in the leadership team and at a high level. In our decentralized structure, he is responsible for his strategy and both of us are at fault for not reaching out to each other.”

Blindspot 14: Losing Touch with Your Shop Floor

Leader Belief

I am in regular contact with customers and have a good sense of how they view our firm. I am also aware of necessary operational details within my organization—knowing what is working well and what is not.

Common Reality

Many leaders lose touch with their customers and frontline colleagues. The majority of their time is spent in headquarters meeting with a small group of senior-level colleagues. Their perceptions of customer needs and operational realities are based on assumptions and outdated information. This tendency to become detached from the business is made worse by a desire to avoid getting into “the weeds” and micromanaging, which some leaders take to mean that they should stay out of the details of the business.

Illustrative Case

A CEO prided himself on being aware of the broader social issues that affected his industry. He also enjoyed working with government leaders on matters of public policy. He wasn't as interested in the internal operational details of his business and delegated these tasks to others. The problem was that the people he selected to perform these tasks were incapable of making the changes needed for the firm to execute at a high level. He also surrounded himself with an entourage who served as a buffer between him and those running the business units, who wanted direct access to the CEO. This CEO's lack of awareness of what was occurring in these groups, and the lack of necessary progress, meant that he was vulnerable both in regard to the firm's performance and his board's perception that he was out of touch with what was occurring in his own firm.

Blindspot 15: Treating Information and Opinion as Fact

Leader Belief

We have an open culture and information comes to me in an accurate and timely manner. We trust each other, sharing information openly and engaging in direct discussions about the problems we face.

Common Reality

Information is often distorted or filtered as it moves up the organization's hierarchy. People are less open and less likely to bring issues to the leader as they seek to protect their own reputations and the reputations of their functions or groups. The leader underestimates how much power dynamics can distort the timing and accuracy of the information he or she receives. In addition, leaders often hear what others believe they want to hear, versus what individuals truly believe (out of deference to the leader's authority or desire to avoid taking a stance that could be proven wrong).

Illustrative Case

The leader of a regional energy company was responsible for building new power plants. Problems arose in one of the key projects with quality standards (which resulted in delays in completing the plant). The head of the project didn't come forward with this issue until the relationship with the vendor building the facility had reached a breaking point. The senior leader was furious and wondered why the project leader didn't come to him earlier when the problems first surfaced. He said, “I could have helped resolve the issues they had but now it is a major problem. I was told that things were under control until this week.” What the leader didn't see was that some of his team members were intimidated by him to the point of being afraid to come forward with issues. They wanted to fix problems on their own before they reached a breaking point. The firm also had an engineering culture in which people prided themselves on solving problems and didn't want to bring problems forward for fear of appearing weak. As a result, project problems were not surfaced until late in the game, resulting in additional risks to the firm and the careers of those involved.

Blindspot 16: Misreading the Political Landscape

Leader Belief

I have positive relationships with members of my leadership team. I also work well with others such as board members and external groups such as the media. When we have issues, we resolve them in a productive manner.

Common Reality

The leader has failed to develop close working partnerships with some key individuals and groups, either within his or her own organization or with external partners or stakeholders. Moreover, the leader doesn't see existing problems in these relationships, often thinking they are better than is actually the case. By the time the leader realizes the depth of the problems, it is often too late. When the issue is brought to the leader's attention, he or she will say, “I hate politics”—not understanding that politics involves influencing, with integrity, those who have an impact on the success of the leader's business.

Illustrative Case

The CEO of a technology firm was brilliant and, by nature, optimistic about his firm's future prospects. He would make statements to the press and analysts regarding the potential of products in his firm's product pipeline. He didn't see a downside to being positive. He also liked the attention he received in the press when making bold predictions about future products. He was warned, however, by his firm's chairman to “tone it down” because the backlash would be severe if the firm didn't deliver on the CEO's public pronouncements. It was also evident to those who knew the chairman that he wanted some of the publicity that was being lavished on the CEO, whom he saw as a self-promoting, even narcissistic, individual. The CEO took the chairman's input as a minor point and not a mandate to change his behavior in dealing with the media or Wall Street. A second issue for the CEO was that he didn't have the talent on his team needed to solve complex technical problems and ensure a robust product pipeline that met shareholder expectations. The CEO, again wanting to be the center of attention, hired people less capable than himself. His team would tell him that they could deliver on his aggressive commitments but then fail to do so. Over time, the products promoted by the CEO arrived late to market and delivered less revenue than expected. The CEO was eventually removed from his role by the firm's board, which was prompted by the chairman's belief that the CEO's leadership style was hurting the company.

Blindspot 17: Putting Personal Ambition Before the Company

Leader Belief

I act in the best interests of my firm and push for what we need to do to improve as a company. I am open and honest with others about my motives and point of view. Overall, no one can question my integrity.

Common Reality

Some leaders allow their personal ambition and need for recognition to take priority over the needs of their company. They are committed to the company's success when it furthers their own success. A few go even further and violate ethical principles and company policies to achieve their goals.7

Illustrative Case

An executive in a large information technology firm cultivated a close working relationship with the CEO and worked tirelessly to meet his own needs. He built coalitions with peers who would support his initiatives and ignored or blocked those who opposed him. His direct reports were given little visibility, and he regularly took credit for their work. He withheld information from peers as he believed it enhanced his own power; he also undermined those he viewed as competitors through subtle but pointed comments about their weaknesses. He did all of this with a pleasant personality and a highly professional image. He believed he was acting in the best interests of his company.

BLINDSPOTS ABOUT YOUR MARKETS

Blindspot 18: Clinging to the Status Quo

Leader Belief

I understand the macro trends in my industry and both the opportunities and threats we face. My team is adapting to changes and innovating at a rate that will sustain our growth. We appreciate what we do well but are not bound by the status quo.

Common Reality

The leader, as well as his or her team, is out of touch with how the marketplace is evolving and the need to innovate at a faster rate. Most members of the leadership team rationalize keeping the current business model, and proposed changes to it are delayed or rejected. The primary concern is protecting the current revenue streams and not making any changes that would threaten near-term performance.

Illustrative Case

A technology firm had a track record of growing at double-digit rates for over a decade, leading the industry segment in which it competes. The firm had been held up as a model of how to act in an entrepreneurial manner. However, the firm's dominant business segment was beginning to see a downward turn in demand. The pundits argued that the new growth in the industry was moving toward IT consulting and support—and away from hardware, which they said would show no growth in the next five-year period. The CEO of the firm held quarterly meetings with his senor leadership cadre and claimed that the predictions of others were mistaken. He stated that he knew better than the pundits where the industry was headed and that his team would prove the critics wrong. As a result, the CEO didn't take bold steps to reduce his firm's cost structure in its base business or to move aggressively, through acquisitions or internal investments, into newer, higher-growth areas. As the firm's key financial metrics declined quarter after quarter, the CEO made the same “stay the course” statements.

Blindspot 19: Underestimating Your Competitors

Leader Belief

I understand the strengths and weakness of our competitors, both those we face off against today and those that may emerge in the next few years. We spend time scouting our competitors and push ourselves to recognize what they do better than we do. This allows us to close a performance gap when needed and learn from their successes.

Common Reality

The leader and his or her team focus more on internal processes and practices than on external competitors. There is a widespread view that success is a given and that there is no need to fear others. When competitors are considered, they are often dismissed as posing little threat, with their products and services viewed as being inferior. The future plans of competitors are largely ignored even when their actions will affect the success of the leader's strategies.8 Competitors may, in many cases, launch a similar product or a lower-cost version, but these potential factors are dismissed as afterthoughts, as most of the leader's effort is focused internally.9 In addition, performance metrics or the way they are applied may distort the performance of the firm in the marketplace in relation to the threat posed by existing and emerging competitors. It is common, for instance, for a firm to measure year-over-year revenue growth but not compare these results to the growth rates of competitors.

Illustrative Case

Steve Ballmer, CEO of Microsoft, is well known for his competitive drive. He regularly takes the stage at company and industry meetings and works himself into an energetic frenzy extolling the virtues of his company and its products. The problem he faces is that too many of his firm's products are uncompetitive when up against the offerings of world-class firms such as Apple, Google, and Samsung. Nonetheless, Ballmer is prone to demeaning Microsoft's competitors and their products. For example, when Apple introduced its smartphone, he commented, “No chance the iPhone is going to get any significant market share,” and later said, “You don't need to be a computer scientist to use a Windows phone and you do to use an Android phone. I can't get excited about Android.” The latter comment was made when Android held 68 percent of the smartphone market, compared to a 3 percent share for Microsoft. Ballmer also had comments to make about his competition in the rapidly emerging tablet market, noting, “I don't think anyone has done a product that I see customers wanting.” His statement was made after Apple had sold over 32 million tablets following the launch of the iPad, creating a new market segment in which Microsoft held only a 1 percent share. While Ballmer finds fault with his competitors, they somehow find ways to develop markets that Microsoft misses, including those for search tools and online advertising (Google), smartphones (Apple, Google, and Samsung), tablets (Apple), social networking (Facebook), mobile music (Apple), and e-readers (Amazon). One of Microsoft's former managers noted, “They [Microsoft] used to point their fingers at IBM and laugh. Now they have become the thing they despised.”10

Blindspot 20: Being Overly Optimistic

Leader Belief

We have a tremendous pipeline of new products and effective growth strategies. Our ability to innovate is among the best in the industry, and we are acquiring firms that can expand our revenue base. We have a clear plan of action, and I strongly believe we will execute at the highest level. The problems we face are minor obstacles. That said, we don't take for granted our future success.

Common Reality

Leaders often overestimate their own abilities and the ability of their firms to avoid problems and risks.11 At a personal level, they may take more credit for successes than is warranted and less responsibility for past mistakes. On an organizational level, they may underestimate the challenges in executing their strategies. As a result, they set unrealistic targets and fail to allocate the time and resources needed to achieve success on particular projects and for the company in total.12

Illustrative Case

Looking to capture new revenue opportunities, an aerospace supply company embarked on an aggressive campaign to acquire firms with products that expanded the firm's product portfolio. The acquired firms would be strategic in helping to protect the company's core business while adding new market segments with higher growth opportunities. The concern was that acquired firms often failed to deliver on their business plans after the acquisition. Some of the problem was due to the way the new firms were integrated into the parent firm, resulting in disruptions in customer relationships and existing management processes. The more significant issue, however, was that the acquisition proposals were too aggressive in projecting future revenues. In essence, the business development staff promoting the deal internally used highly optimistic scenarios in order to sell their deals. Those who raised concerns were seen as being “negative” and focused only on “saying no”—and, in so doing, not taking the risks required to promote growth. Once an acquisition was finalized, those running the new business inherited unrealistic plans that in many cases could not be achieved.

OBTAINING FURTHER BLINDSPOT FEEDBACK

In the last chapter, I suggest several approaches for assessing your blindspots. You can gain additional insight by considering the twenty common blindspots in this chapter. This can be done by giving the worksheet (“Common Leadership Blindspots: Feedback Worksheet”) in Resource C to a trusted confidant and asking him or her to identify your “top three blindspots.” You then want to have an informal discussion with this individual, probing for more detail as needed, including specific examples of your blindspots and recommendations for addressing them.