CHAPTER TWELVE

A FRAMEWORK FOR CHANGE

Capacity, Competency, and Capability

Brenda B. Jones

Change in itself is a profound reality. Most organizations realize that the fast, ever-increasing rate of change they’re currently experiencing is a critical part of today’s business environment. And a permanent one. Yet, creating and institutionalizing responses to this rate of change in a way that truly aligns an organization such that it can achieve its mission and compete in its environment is a constant dilemma. This seems true from across all organizations—for-profit and non-profit. Change is occurring throughout all aspects of the organization such as in management practices and processes. The truth is that too many companies are hard-pressed to leverage the opportunities and challenges of change (Jones, 1999).

General ambivalence exists regarding change in organizations, and seemingly a frustration that individuals are carrying. Even when individuals find some success with their personal change processes, their work in groups is less satisfying. In addition, the organization’s effort to structure itself, effectively define its culture, create new systems and processes, and utilize its people is less than adequate. This is true, even in those cases when a change strategy is accurately identified and supported. Too often, what is ultimately created does not necessarily enhance the organization’s ability to compete in the marketplace, reposition itself competitively, or invent the future.

Even in these times of major disasters, emerging conflicts, and greater uncertainty about the future, the human spirit continues to triumph and rise to meet the challenges of life. Having a clearer understanding of what needs to change and how change can occur is a growing realization that many tried-and-true methods of managing change are no longer effective and need to be more relevant for today’s world.

This chapter explores a framework that helps to diagnose, take action, and measure success at all levels of system—individual, group, and organization—in relation to the internal and external environment. The focus examines some elements of change that align with the needs of the change process and provide a useful understanding for learning, growth, development, change, and transformation.

Underlying Bases of Organization Development

Change management has been around for some time with primarily a mechanistic viewpoint. Organization development (OD) is grounded in the behavioral sciences with the premise of change primarily grounded in a humanistic perspective. Some of the characteristics of OD align with:

- An applied science—behavioral sciences address organizational issues providing insights into human behavior as it relates to the workforce; premises are developmental or based in action research to validate hypotheses.

- A value system—this brings about change in a predetermined direction and interprets increased concern with the human capital of the organization with an assumption that both the organization and the individual benefit.

- Optimistic—this is the innate potential of individuals to be productive, independent, and capable of contributing positively to the objectives of the organization.

- Oriented toward economic objectives—utilizing individual and group potential to achieve organizational goals and performance that can achieve strategic and financial success.

- Environment—internal and external climates provide opportunities for appropriate responses to conditions for an effective workforce and a competitive advantage.

- Use of groups—the functionality and effectiveness of groups increase to potential for carry out organizational goals.

- Participation—engagement of the workforce represents levels of involvement, commitment and passion about the work in the organization.

Viewing Change from a Systems Perspective

Organizations need to proactively respond to complex and turbulent challenges and opportunities. Complexity requires us to raise our individual levels of thinking, doing, and being and the levels of our collective relationships/social systems. Systems are the overlapping, reinforcing, and interrelated nature of the system’s components. A system exists in relation to its environment. The systems perspective is the process of taking into account all of the behaviors of a system as a whole in the context of its environment. Development or improvement is geared to benefit all parts of the system and each part is responsible for its respective function, position or structure.

A systems perspective to organizational change and effectiveness must include the development at multiple levels of the system—individuals, groups, and the organization separately and as a whole. It is in the level, the intersections of the levels, and the collectiveness of the levels that the most significant elements of change can occur. A change at one level of a system can affect either negatively or positively all other levels. To move in the direction of the change goals, each level of system is always operating in relations to each other and its environment. Characteristics of each level include:

- Organizations as dynamic entities are characterized by a shared mindset and the goal of pervasive change. They have on a large scale all of the qualities of the individual, including beliefs, ways of behaving, objectives, personality, and motivations. An organization operates with inputs, processes, responses/feedback and outputs. This model builds understanding of the overall effects of a change process.

- Groups function as independent entities or subsystems of the larger system. There are significant implications of groups that influence the behaviors of individuals. Members of the group will have their own truths and the group may not have the same truth at the same time. The common purpose, interdependent status, roles, relationships, norms, and values help the group function and are important to clarify and achieve the group’s outcomes.

- Individuals are single, separate organisms who can be both independent and a part of other systems. Individuals possess needs, motivations, and goals that must be met through work and life. The self in relation to its environment can regulate to maintain its own health and well being.

A Framework for Organization Development and Change: Three C’s

Successful change work can be improved with an examination of these concepts: capacity, competency, and capability. Figure 12.1 represents the independence of these concepts, which provides a unique point of view of a whole picture. Organizations consistently face an unprecedented rate of change in technology, their changing workforce, and competition in the global environment and the need becomes greater to attract, manage, develop, and lead the human capital of the organization with its complexities and growing demands. While capacity, competency, and capability are frequently used words, most often they are used interchangeably. In many situations, any one of the three words is used with the same meaning of another or to define the other words.

FIGURE 12.1. THE THREE C’S MODEL

The language used to talk about capacity, capability, and competency has overlapping and shared meanings, and this apparent sameness in meaning is misleading. Consequently, definitions are not as clear and it is most often in the push for clarity that change can occur. In the exploration of the meaning and differences among these words, an OD practitioner can lead the client to a review of unexamined areas in which lie the potential for new understandings, deeper insights about their meaning, and distinctive perspectives relevant to their change process. From these new perspectives emerge actions that result in organizational change and can produce a competitive advantage.

Capacity

Capacity is the overall framework of an organization that drives and creates its future. Capacity, as the container, gives the clearest focus and widest view of what is possible and the organization’s internal potential for success. The container would represent a boundary that is the basis for creating and defining the organization as an entity. The container holds the direction for the organization’s internal and external focus, short-term responses, long-term strategy, and deep meaning and understanding about the system itself. Ultimately, the organization identifies its capacity taking an inside looking out stance and is fully aware of the conditions that exit in its environment. Capacity can be described in part using the term “clock building” used by Collins and Porras (2002): “It is the importance of building an organization’s ‘core value system’ instead of relying on great product ideas, charismatic leaders, and paying too much attention to profit.” In assessing capacity, the organization sees the view of the boundaries that hold its regulations, technology, people, and culture, especially those values, beliefs, and assumptions that are the underpinnings of major change. Capacity identifies whether the organization can understand customers’ needs, build key business partnerships, create strategic infrastructures, and attract and retain the best people to its workforce. It also determines whether the organization has the tools to be effective in identifying and serving diversified, changing markets.

In understanding capacity, the broadest set of processes using internal and external factors must be considered to help define the best position for the organization to be successful. This positioning generates questions to be asked and in order to know the current state of the organization to more fully support its growth and sustain itself long term. Most CEOs want to optimize return on the organization’s resources to produce exceptional results and achieve profit and financial sustainability with the confidence of being competitive in the marketplace, providing a unique product, and having an effective organization. There is no doubt the questions are complex.

Capacity considers what the organization can live in or up to embodying the scale or scope of its collective value or worth, the fit to its real purpose, and its ability to have an impact in the world. Whether an organization focuses globally and/or locally, capacity defines a way to determine its outreach or boundaries of operating and describes the scale or scope of its direction, work, and action.

Questions to ask about capacity include:

- Do we understand our business environment and the marketplace in which we operate?

- Are we aware of the changing technological, political, economic, and socio-cultural and industry trends that have strategic implications for our business?

- Are we clear about our identity and brand?

- Are we clear about what we stand for—our mission and values?

Competency

Competency is a critical aspect of an organization’s strategy and success. Today there is even more emphasis on recruiting and hiring processes and practices matching the organizational needs and gaps with the right individual who has the right range of skills and talent. Components of competency are knowledge, skills, attributes, mindsets, and behaviors required to produce and improve organization’s competitive advantage and achieve its results. Each individual, group, and the organization itself have core sets of competencies that are significant assets to help the organization outperform competitors and leverage the strength of its workforce. Competencies can themselves be a major differentiator for an individual and organizations to be compared to others and be competitive in the marketplace.

Leaders and managers must identify and develop their talent to meet the constant need for new competencies and grow their organizations. Hiring talent is imperative in the changing demands of the 21st century workforce as organizations must continuously monitor both the internal and external environment, link strategic and operational change, and manage their human capital resources in a world that is changing at an increasingly rapid pace. There has to be a commitment to the utilization of a broader and more diverse range of talent. The complexities involved in new innovations, new markets, and social change efforts require levels of talent and other competencies to achieve major shifts in bringing products to market, as well as an increase in the speed of the change and the response and interest of the market to the product.

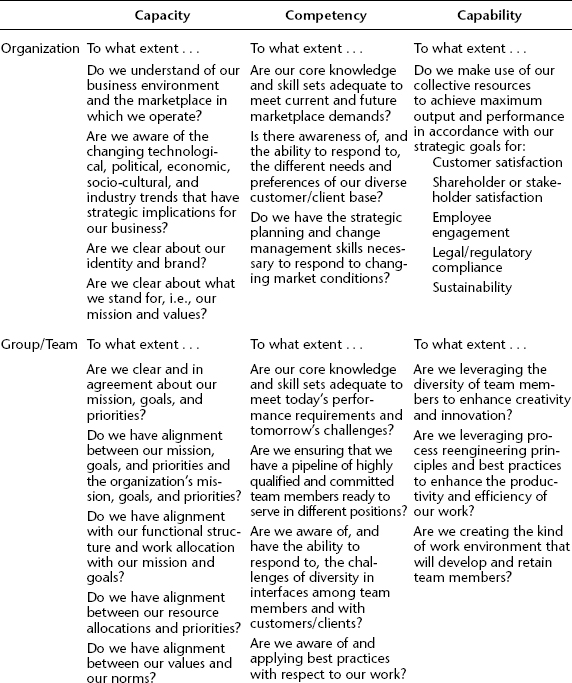

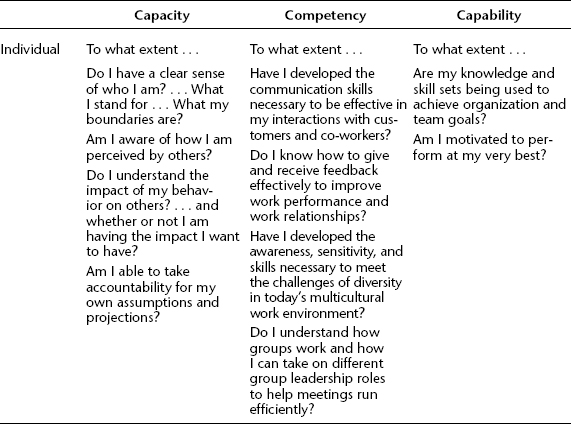

It is unlikely that an individual or organization can achieve success without having the right set or combination of competencies. Competency grows through experience and, to the extent the individual or organization learns and adapts and therefore can develop a broader range of competencies related to specialization, craftsmanship, expertise, and intelligence. To have a certain level of competence, there is a need to interpret a situation in its context and have a repertoire of possible actions. In most situations, the individual and organization have begun to draw from its capacities and define further its capabilities. Table 12.1 outlines the Three C’s Model across three levels of system.

TABLE 12.1. THREE C’S MODEL AND LEVELS OF SYSTEM

Questions to ask about competency include:

- Are our core knowledge and skill sets adequate to meet current and future marketplace demands?

- Is there awareness of, and the ability to respond to, the different needs and preferences of our diverse customer/client base?

- Do we have the strategic planning and change management skills necessary to respond to changing market conditions?

Capability

Capability embodies the uniqueness of an organization’s performance and what it is known for when it is at its best. It represents the execution of its internal processes and systems that addresses customers’ needs and is distinguishable with others in the marketplace. An organization leverages its resources through individuals, teams, groups, and work across boundaries in alliances, partnerships, and key relationships for successful outcomes that add value and achieve the organizational strategies and goals. Clear choices made in getting the most out of its core sets of competencies in the organization build capability.

In assessing capability, the organization maximizes the sum of the known and unknown, seen and unseen, intended and unintended factors driving it to its desired end results. Capability is seen when leaders lead with strategic intention and people feel personally connected to the organization with an investment in how performance affects the organization’s future. Every individual and group in the organization is focused on work that has impact on the collective achievement of organizational goals.

Capability capitalizes on answering the right questions and achieves concentrated and motivated results that allocate resources for quality that exceeds expectations, strengthens relationships and commitments with customers and employees, and builds a reputation for innovation in its ideas, products and services.

Questions to ask about capability include:

- Do we use our collective resources to achieve maximum output and performance in accordance with our strategic goals for:

- Customer satisfaction,

- Shareholder or stakeholder satisfaction,

- Employee engagement,

- Legal/regulatory compliance, and

- Sustainability.

- Are we clear about our uniqueness?

- Do we leverage opportunities for major impact?

- How does what we do and plan to do fit our requirements for the future?

The framework in Table 12.2 can help you look at the complexities, paradoxes, and choices in the process and to move from the present state to the desired state.

| Defining | Describing | |

|---|---|---|

| Capacity | Identity, Brand | Mission/Vision/ |

| What we stand for | Values | |

| Mindsets | ||

| Competency | Skills | Talent |

| Knowledge | Behaviors | |

| What we know/do? | Expertise | |

| Capability | What are we known for? | Org. Processes |

| How do we perform/function? | Use of Resources | |

| Uniqueness |

TABLE 12.2. WORKING WITH ORGANIZATIONAL CHANGE: DEFINING AND DESCRIBING

Meaning of This Framework

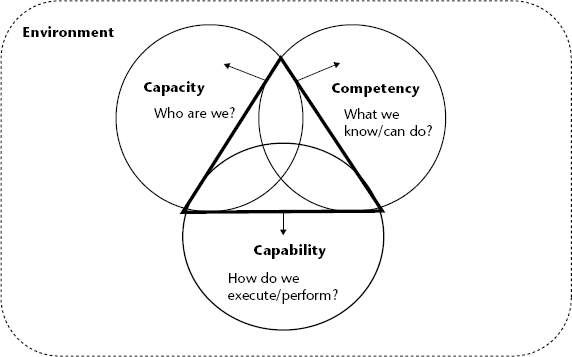

Capacity, capability, and competency are linked in linear, circular, and random ways to each other. In any given client system, any one of these three C’s can be a starting point for the organization in its pursuit of change. For many organizations, the starting C is based on the one that has the largest gap of what is missing or what is most needed to meet the internal and external conditions and demands. Each one of the C’s permeates the other two and in significant ways represents aspects and the essence of chaos and complexity—there always is connection, interdependence, and order, however difficult it is to detect. Greater understanding of the three C’s can be deciphered in the field that exists in the separate and overlapped areas of the model with a recognition that each C is embedded with multiple meanings (see Figure 12.2).

FIGURE 12.2. THE EMBEDDED THREE C’S MODEL

There is natural overlap in these concepts and, once the differentiation is understood, these overlapping areas contain potentially valuable new knowledge and perspectives on the organization. The outcome of a successful change process can be improved when the centering emphasis is on integrating the concepts of capacity, capability, and competency. Individual, group, and organization performance in each of these areas has to occur simultaneously. These concepts cannot be addressed singly or independently; to be successful they must be assessed, tracked, and measured concurrently.

In a complex, global environment, this is not news. Every change effort asks even more difficult questions than it answers. Consequently, meaningful and sustaining change cannot be anything but difficult to accomplish. One response to this dilemma is creating a deeper understanding of the concepts of capacity, capability, and competency and using them in an integrated way.

Successful change work demands an examination of each of these concepts as one unique, whole picture. These three concepts represent one source, among many useful models, for creating the kind of change that develops competitive advantage. When an organization effectively analyzes the external trends that impact it and its marketplace, it can construct strategies and actions based on this new knowledge. It is in these specific links to business efforts that more significant gains are accomplished.

This knowledge of the overlapping of capacity, competency and capability can produce the actions, both internal and external, that support creativity, innovation, and adaptability and differentiate itself and its product or service. With each level of system is a range of change from a lesser amount of change to a maximum effort from the change process, which creates the beginning of another process.

Organizations and individuals often use one of the three C’s to actualize the entire change process through that one area which eventually becomes inadequate. While working on one C is always producing development of the other two C’s, it may not be developed to the degree that is needed for the required success. There must be a context for the change and a direction even though the distinction is not as clear as one would expect. In this approach each C has to lead to a maximum effort and a commitment to ultimately integrating all three of the C’s for maximum results.

The Process of Transformation

Many interactions and, therefore, experiences of change, are transactional and incremental. To achieve transformation the dynamic of change increases with exchanges at a boundary and finding a new place well beyond where the effort started. Figure 12.3 shows the overlapping circles with triangle and arrows and the T, standing for transformation. Transformation is the highest level of integration with all three C’s, which brings about the emergence of a new state of being through a complete shift, even the death of the old state of being.

FIGURE 12.3. THE 3 C’S FRAMEWORK WITH OVERLAPPING TRIANGLE

Transformation is more than simply adding information into the container that already exists. Transformation is about changing the very form of the container—making it larger, more complex, and more able to deal with multiple demands and uncertainty. Transformation occurs, according to Kegan (1994), when you are newly able to step back and reflect on something and make decisions about it. Kegan says transformative learning happens when someone changes, “not just the way he behaves, not just the way he feels, but the way he knows—not just what he knows but the way he knows” (p. 17).

Schön (1973) indicates that the loss of the stable state means that our society and all of its institutions are in continuous processes of transformation. We cannot expect new stable states that will endure for our own lifetimes.

We must learn to understand, guide, influence, and manage these transformations. We must make the capacity for undertaking them integral to ourselves and to our institutions.

We must, in other words, become adept at learning. We must become able not only to transform our institutions, in response to changing situations and requirements, but we must invent and develop institutions which are “learning systems,” systems capable of bringing about their own continuing transformation.”

The task, which the loss of the stable state makes imperative, for the person, for our institutions, for our society as a whole, is to learn about learning.

- What is the nature of the process by which organizations, institutions, and societies transform themselves?

- What are the characteristics of effective learning systems?

- What are the forms and limits of knowledge that can operate within processes of social learning?

- What demands are made on a person who engages in this kind of learning?” (Schön, 1973, pp. 28–29)

Donald Schön argues that social systems must learn to become capable of transforming themselves without intolerable disruption. In this “dynamic conservatism” has an important place. “A learning system must be one in which dynamic conservatism operates at such a level and in such a way as to permit change of state without intolerable threat to the essential functions the system fulfils for the self. Our systems need to maintain their identity, and their ability to support the self-identity of those who belong to them, but they must at the same time be capable of transforming themselves” (Schön, 1973, p. 57).

The Three C’s Framework is applied to a case history summary description in Exhibit 12.1 and used for an analysis of the case history in Exhibit 12.2.

Learning and the Process of Change

The desire to learn is critical to the change process. Change is a difficult and energy-consuming process and cannot be sustained without sufficient internal motivation. When there is a genuine desire to learn new options, change begins, either consciously or unconsciously. Alternative ways of thinking and action are tested against experience, refined, and then adopted or rejected. The process of change involves destructuring (taking apart old forms, perspectives) being open to what is new, missing, or does not fit any longer, and then allowing the pieces to re-form themselves into a new whole. The general pattern is

- Action plan. New goals are set, and related behavior or procedures planned.

- Trial. Alternative behavior or procedures are tested for effectiveness.

- Feedback. Results of the new action or behavior are indicated by any obvious consequences and the honest reactions of a support system.

- Plan revision. Goals and actions are assessed according to their consequences and the feedback received is revised or replace by alternative plans. The cycle of testing and revising continues until feedback indicates that new behavior or procedures meet their goals. (Johnson, n.d.)

Learning is a restructuring process involving a choice between alternatives and/or dealing with multiple possibilities and polarities. It is the dynamics of the process through which one makes meaning of one’s experience. It is from the integration of many factors that something new emerges and we can say that learning and change have taken place. New attitudes and behaviors that survive the testing stage are stabilized through assimilation of personal value systems, relationships with others, and organization norms.

Internal Integration

New ways of thinking and acting will remain stable only if they are successfully integrated into the system of forces that determine an individual’s character and personality and the external environment:

- Value system. Attitudes or practices that are inconsistent with a person’s value system will soon be disconfirmed and rejected. A conscious effort must be made to identify and resolve value conflicts.

- Intellectual frameworks. If new ideas are to be viable conceptual tools they must be logically integrated with established theories.

- Personality. New behavior must be consistent with an individual’s personal style, or it will require too much emotional energy to maintain and will appear false.

The personal integration process is internal and largely unconscious. However, chances for stabilization of new behavior patterns are increased if the process is considered consciously and inconsistencies are brought to the surface and discussed with others. Successful integration of new ideas and practices enlarges an individual’s personal resource base, leading to increased competence and self-respect.

External Integration

Learning is a change in behavior as a result of one’s experience. Learning requires the individual or organization to utilize self-understanding as it interacts with the other and its environment. If new assumptions and behavior are to last, they must also be compatible with the external environment in which the system functions.

- Relationships and roles. Changed behavior disrupts the expectations of others and alters an individual’s “role” or position in the network of interrelationships of which he or she is a part.

- Organization norms, values, policies, and procedures. New attitudes and behavior are likely to be disconfirmed and abandoned sooner or later if they are in conflict with those of the organization. New practices must be integrated into organization procedures and confirmed by organizational policies if they are to remain stable. This integration factor is one of the most difficult to influence and also one of the most important if the change is to be reinforced. (Johnson, n.d.)

Success of the Change Framework

Capacity, competency, and capability form a framework that is both simple and complex. It is in the independent and interdependent development of these concepts bridging across a multitude of factors that bring about change and transformation for organization success. A total effort for change must be planned and implemented over a period of time that continues to provide stability for the organization to move forward. The organization will still encounter many changes with its strategy for growth and sustainability, if it is to be competitive and have an impact in the world. Support for the success of the three C’s includes:

- Leadership. An organization must have a high quality of leadership fully committed to its mission and its people with a collaborative leadership team. The leader needs an ability to deal with change and transformation effectively; understand the business, communicate a clear vision and strategy, and take responsibility for learning and growth.

- Internal and external organizational scan. A successful organization is aligned with its internal structure, people and processes, and its external climate consistently to best position itself for change. There must be a talented workforce and a developed performance oriented culture.

- Orientation for change. Change is embraced and welcomed by the total organization at all levels of system. Change is seen as a way to be relevant, innovative, and effective in the planning and implementation processes and in anticipating the future. There must be a greater openness for what one does not know, as opposed to what one knows, that improves the organization’s agility.

Conclusion

The planning, managing, facilitating, and implementing of change is an ongoing process. It is, by definition, the essence of the work of the field of organization development (OD) and, therefore, the OD practitioner. Change is an ever-evolving phenomenon and societal, economic, technological, climate, and global shifts are major factors influencing the change process. As an organization reaches one level of effectiveness, it encounters continuous experiences of emerging internal and external changes and continuously experiences internal and external changes. New challenges and opportunities must be anticipated, prepared for, and addressed at strategic and tactical levels.

While the concepts of capacity, capability, and competency are not new—individually and collectively—they are a bridge to the interpretation of the change process from a macro level to a micro level. Most great organizations that have longevity, strong brands, and a resilient market presence are adept in the three C’s and continually transform to meet the challenges of an ever-changing global marketplace. They are pathways from the strategic or tactical level to understanding the ways an organization can implement and support systemic change. For a consultant, these concepts make sense out of the complexities of change. The analysis and application of the three concepts will offer any organization an opportunity to broaden and strengthen both its strategy and implementation efforts in addressing current and future business challenges. Most importantly, because of the myriad changes in organizations, everyone is responsible for his or her role, responsibilities, and understanding of the complexities involved in managing him- or herself, time, resources, and day-to-day results. The overlaps and intersections of three C’s can provide new ways of working and giving attention relative to the change process and to our evolving organizations, society, and culture.

References

Bennis, W. G., Benne, K. D., & Chin, R. (Eds.) (1969). The planning of change. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Collins, J. C. (2001). Good to great: Why some companies make the leap and others don’t. New York: HarperCollins.

Collins, J. C., & Porras, J. I. (2002). Built to last: Successful habits of visionary company. New York: HarperCollins.

Ghitulesco, B. E. (2013, June). Making change happen: The impact of work context on adaptive and practice behaviors. Journal of Applied Behavioral Sciences, 49(2), 206–245.

Johnson, V. H. (n.d). Change process paper from presentation. Cleveland, OH: Gestalt Institute of Cleveland.

Jones, B. B. (1999). Capacity, competency and capability. OD Network Practitioner, Journal of the Organization Development Network, 31(1).

Kauffman, D. L. (1980). System one: An introduction to system thinking. Minneapolis, MN: Future System, Inc.

Kegan, R. (1994). In over our heads: The mental demands of modern life. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Kegan, R., & Lahey, L. L. (2001). How the way we talk can change the way we work. Seven languages for transformation. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Kotter, J. P. (2012). Leading change. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Review Press.

Lippitt, G. L. (1973). Visualizing change: Model building and the change process. Fairfax, VA: NTL Learning Resources.

Quinn, R. (1996). Deep change: Discovering the leader within. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Phyllis, J. A. (Producer) & Orion, T. (2003, January). Interplast [video]. Prepared as a basis for discussion. Retrieved from: http://csi.gsb.stanford.edu/interplast

Rush, H.M.F. (1969). Behavioral science: Concepts and management application. New York: National Industrial Conference Board.

Schein, E. H. (1993, Autumn). On dialogue, culture and organizational learning. Organizational Dynamics, 22(2), 40–51.

Schön, D. (1973). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Retrieved from http://infed.org/mobi/donald-schon-learning-reflection-change (p. 57).

Schön, D. (1973). Beyond the stable state. Public and private learning in a changing society. New York: W.W. Norton.

Tocquigny, R., & Butcher, A. (2012). When core values are strategic: How the basic values of Procter & Gamble transformed leadership at Fortune 500 companies. P & G Alumni Network, Inc. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: FT Press.

Ulrich, D., & Lake, D. (1990). Organization capability: Creating competitive advantage. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Ulrich, D., & Smallwood, N. (2004, June). Capitalizing on capabilities. Harvard Business Review.

Wheatley, M. J. ( 1992). Leadership and the new science: Discovering order in a chaotic world. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler.