CHAPTER THIRTY-FOUR

THE FUTURE OF ORGANIZATION DEVELOPMENT IN A VUCA WORLD

Roland E. Livingston

“No man ever steps in the same river twice.”

—Heraclitus

“Nothing is permanent but change.”

—Heraclitus

Introduction

The fact of the matter is, organization development has been changing and evolving since its introduction in the 1940s. It is not the same river that it was, nor will it ever be so. Organization development has evolved from its roots in the 1940s and 1950s, through a period of foundational development in the 1960s and 1970s, through the emergence of new branches in the 1980s and 1990s, to the creation of new OD approaches and practices in the 2000s.

While the field of OD has been experiencing this evolution, organizations of all kinds have been evolving as well. Management and organizational theory have undergone a significant transformation. As changes have developed in technology, the global economy, and social structures and patterns since the mid-20th century, forward-thinking leaders in the corporate world have begun to realize that they must embrace a new paradigm. This new way includes management and operational structures that are flat, rather than hierarchical, and that are more responsive to the external environment, more flexible, and better prepared to give customers what they want. This is the environment in which organization development must remain relevant and viable and add value.

Bob Johansen, a sociologist with the Institute for the Future (IFTF), writes in his book Get There Early (Johansen, 2007) that “The external future forces . . . require a sense of urgency,” and that organizations need to reflect, tune, and design flexible approaches to deal with the future. Johansen indicates that we may never get to the end point to which we are moving. He states that “direction, not destination” sets us up for the future. He also says we are

- Moving toward everyday awareness of vulnerability and risk in both the developed and developing worlds;

- Moving toward an hourglass population distribution where old age is the new frontier, but the kids will be heard. The young “digital natives” . . . were born into and unconsciously bred for the emerging world of dilemmas and global connectivity;

- Moving toward deep diversity that is “beyond ethnicity,” in the workplace and in society. Diversity is a dilemma in itself, and it presents major challenges as well as exciting opportunities for innovation. Diversity is essential to creativity;

- Moving toward bottom-up everything, where people interact with the products and services they consume. New types of loosely connected teams will become the new basic organizational unit for innovation. Hierarchies will be important in some cases, but they will come and go in much more fluid ways;

- Moving toward continuous connectivity where network connections are always on. Online identities will become increasingly important as people learn to express themselves . . . and leaders learn to exert leadership . . . in new ways that are consistent with the new media while still linked to the old media;

- Moving toward a booming health economy in which health is an important filter for many purchasing decisions. Health values will be central as consumers become more health conscious; and

- Moving toward mainstream business strategies that include environmental stewardship combined with profitability—doing good while doing well. Environmental practices and sustainability strategies will become increasingly common and increasingly urgent. (pp. 25–27)

This is the emerging world into which OD practitioners and academicians must step in order to assist leaders and workers learn to deal with the new reality, a world characterized by volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity (VUCA). The volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity inherent in organizations today is the new normal. VUCA is changing not only how organizations do business, but also how organizational leaders and employees operate. The knowledge, skills, and abilities once needed are no longer sufficient. Today we need organizations that are more strategic and capable of using critical thinking skills to adapt to volatility and uncertainty.

VUCA Defined

The acronym VUCA was coined by the military in the late 1990s and accurately pegs what is happening in a rapidly changing and increasingly unstable world.

The “V” stands for volatility, the nature, speed, volume, and magnitude of a pattern of change that is non-predictable (Sullivan, 2012a). A study by the Boston Consulting Group (2013) found that one-half of the most turbulent financial quarters during the past thirty years have occurred since 2002. The study also concluded that financial turbulence has increased in intensity and persists longer than in the past (Sullivan, 2012b). Among the drivers of turbulence in businesses today are digitization, connectivity, trade liberalization, global competition, and business model innovation (Reeves & Love, 2012).

The “U” stands for uncertainty. Kinsinger and Walch (2012) called this the lack of predictability in issues and events. Such volatile times make it difficult, if not impossible, for leaders and others in organizations to use past issues and events as predictors of the future. Needless to say, this makes forecasting extremely difficult and decision making challenging (Sullivan, 2012a).

The “C” stands for complexity. There are often numerous and difficult to understand causes and mitigating factors (both inside and outside the organization) involved in any problem. This layer of complexity, on top of the turbulence of change and the absence of past predictors, adds to the difficulty of decision making. It also leads to confusion, which can cause ambiguity.

The “A” is for ambiguity, a lack of clarity about the meaning of an event (Caron, 2009) or, as Sullivan writes, the “causes and the ‘who, what, where, how, and why’ behind the things that are happening [that] are unclear and hard to ascertain” (2012a). A symptom of organizational ambiguity, according to Eric Kail (2010), is the frustration that results when compartmentalized accomplishments fail to add up to a comprehensive or enduring success.

The VUCA model describes the internal and external conditions affecting organizations today. With VUCA being the reality, it is clear that OD must help clients respond to it.

The Past

It is helpful to look at where the field is and how it got there. The workplace itself, according to Crandall and Wallace (1995), underwent two major shifts in the second half of the 20th century. Early in the century, the Industrial Revolution gave birth to the bureaucratic system that was favored from the 1950s until the 1980s. In this system, jobs were rigidly defined, rules and policies were strictly enforced, and a hierarchy of authority controlled all decisions. The bureaucratic design in organizations used many levels of managers, each of whom had dominion over a highly discrete division. Workers had strictly defined roles and assignments and performed tasks individually. This is the system in which OD had its birth.

In the first major shift, the bureaucratic system was replaced by the high-performance system. This approach, common since the 1980s, emphasized workers on teams that collectively were made responsible for a wide range of activities in business processes and were also expected to initiate improvements to the processes.

A second shift, to a virtual workplace, is currently underway. Whereas the high-performance system pushed the boundaries of the bureaucratic approach, the virtual workplace design dissolves the boundaries. In a virtual workplace, people do not always work in the same place or at the same time (Crandall & Wallace, 1995). Electronic modes of communication connect people who rarely come together in person as they perform various work tasks. The traditional concept of a “job” has vanished; organizational systems are now designed to be in tune with the capabilities of individual workers. Full-time employees use core competencies on a continuous basis, while part-time employees are used to add needed core competencies on a just-in-time basis; often, the virtual workplace relies on specialists who are used on an ad hoc basis (Crandall & Wallace, 1995).

Organizations have looked for ways to decrease layers of management and to streamline structure. Even after the economy improved, the new structure remained; business leaders realized that the leaner, flatter design allowed for quicker reactions to the business environment.

This flatter arrangement, which Lawler (1992) called a “high-involvement structure,” involves individuals throughout the organization in the information flow and decision-making capacities. This approach is consistent with Lewinian democratic principles and may be especially appropriate in an increasingly democratic world. It is also in line with the shift to the new knowledge-based economy, in which knowledge has a greater value than capital, equipment, natural resources, or land (Helgesen, 1999). Technology also supports a high-involvement approach to management. Flexible, organic, and interactive, today’s technology pushes information, and therefore power, to those on the front line and thereby facilitates the direct communication needed for decision making.

The Future

In 2012 the Institute for the Future (IFTF) reported that the economic disruptions seen in traditionally dynamic regions during the last decade reflect a pattern that is likely to continue, and may even spread. A combination of government fiscal constraints and technology-driven market developments continues to reshape the structure of economic systems. Open source protest movements, such as the Arab Spring in a number of North African nations and the emergence of the Occupy Wall Street protests in the United States, are likely to become more common. The digital revolution increasingly enables organizations to move straight to mobile communications that facilitate organizational and banking services. This will enable alternative growth and development paths and necessitate new approaches. In short the old rulebooks will no longer apply.

Individuals are faced with the need to adapt to many changes themselves. It is very difficult for many to say, “I work a 9 to 5 job.” Individuals must become comfortable with a 24/7 model. There is a lack of predictability about how work time is distributed. As people move from place to place, being comfortable with the uncomfortable will become more important.

In his book The World Is Flat, Thomas Friedman (2005) stated: “Whenever civilization has gone through one of these disruptive, dislocating technical revolutions—like Gutenberg’s introduction of the printing press—the whole world has changed in profound ways. But there is something different about the flattening of the world that is going to be qualitatively different from other such profound changes: the speed and breadth with which it is taking hold. . . . This flattening process is happening at warp speed and directly or indirectly touching a lot more people on the planet at once. The faster and broader this transition to a new era, the more likely is the potential of disruption.”

The challenge faced by the OD field is to help organizations navigate the complexity of a VUCA world. Organizations have to figure out how to be resilient and agile in the face of changing circumstances.

OD practitioners and academicians must adapt their practices in response. VUCA represents a continuation and speeding up of the transformation we are already undergoing. Today, change is the dominant theme. In the United States and many other countries, every week seems to bring another technological innovation; a continuous stream of new hardware and software makes communication faster, commercial trade easier, and information of all kinds more accessible. At the same time, significant changes are taking place in cultural, political, economic, scientific, and sociological institutions. We are in the midst of a great shift from an industrial economy to an economy based on information. People are living longer. National economies are becoming ever more interdependent, and increasing numbers of nations are active in a global market economy.

One might say that, by all accounts, the “new normal” for organizations of all kinds is real. The financial crisis of 2008–2009, for example, shattered many business models. Financial organizations, manufacturing organizations, and service organizations throughout the world were plunged into turbulent environments. At the same time, changes in technology moved forward. Social media now challenges, and has virtually supplanted, the mainstream media in delivering “news.”

VUCA is taxing leaders, who are finding their skills growing obsolete as quickly as their organizations change in this volatile, unpredictable landscape. Agility and adaptability are the most needed skills. As Horney, Pasmore, and O’Shea, authors of “Leadership Agility: A Business Imperative for a VUCA World,” note [to succeed], “leaders must make continuous shifts in people, process, technology, and structure. This requires flexibility and quickness in decision making” (Horney, Pasmore, & O’Shea, 2010).

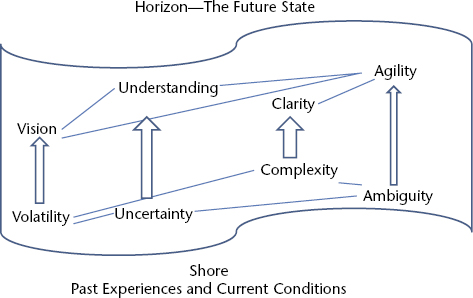

Organizations must figure out a way to change the acronym to represent Vision, Understanding, Clarity, and Agility. This flip in meaning was proposed by Bob Johansen of the Institute for the Future. Johansen said that the best leaders are characterized by what he calls VUCA Prime, those individuals who are able to use their leadership skills to help make sense of leadership in a VUCA world.

Moving to VUCA Prime

In the VUCA Prime world, volatility can be countered with vision, which is even more vital in turbulent times. Uncertainty can be countered with understanding, the ability to stop, look, and listen. Complexity can be countered with clarity, to make sense of chaos. Organizations that can quickly and clearly tune into all of the minutiae associated with chaos can make better, more informed decisions. Finally, ambiguity can be countered with agility, the ability to communicate across the organization and to move quickly to apply solutions (Kinsinger & Walch, 2012).

Figure 34.1 represents the river that OD practitioners and academicians must navigate, while assisting organizations and individuals make the crossing as well. As the figure shows, there is no clear passage from VUCA to VUCA Prime. Crossing successfully requires partnering with client systems in order to make sense of the new normal. The opportunity and the imperative for the OD field is to find one voice that describes what OD has to offer to organizations facing VUCA. The disparate OD organizations must find a way to speak clearly and convincingly, in terms that client systems can understand. VUCA must be a topic in the many OD programs offered at educational institutions across the globe. New entrants into the field must know both the history and values of organization development that the field is changing. In short, OD is also facing a new “normal.”

FIGURE 34.1. MOVING FROM VUCA TO VUCA PRIME

One company that has responded to the new normal is Unilever. In 2010, Unilever pledged to double the size of its business in the next ten years while reducing its environmental footprint and increasing its social impact (one of its subsidiaries is Ben & Jerry’s ice cream, known for its socially responsible business practices). Sustainability has become a central component of Unilever’s new business model, one that is based on VUCA principles. Keith Weed, chief marketing and communication officer for Unilever, told Forbes magazine’s Avi Dan:

“We look at the world through a lens, which we call VUCA. . . . So you can say that ‘it’s a very tough world,’ or you can say, ‘it’s a world that’s changing fast, and we can help consumers navigate through it. . . . The digital revolution, the shift in consumer spending, all this suggests that companies have to reinvent the way they do business.” (Dan, 2012)

In some respects, decision making today is not different from what it was when the field of organization development began. The field has developed over time, largely through the work of practitioners. Among the early practitioners were such individuals as Kurt Lewin, Richard Beckhard, David Bradford, and many others. The values of the field articulated by Margulies and Raia (1972) and subscribed to by most academicians and practitioners follow:

- Providing opportunities for people to function as human beings rather than as resources in the productive process;

- Providing opportunities for each organization member, as well as for the organization itself, to develop to his or her full potential;

- Seeking to increase the effectiveness of the organization in terms of all of its goals;

- Attempting to create an environment in which it is possible to find exciting and challenging work;

- Providing opportunities for people in organizations to influence the ways in which they relate to work, the organization, and the environment; and

- Treating each human being as a person with a complex set of needs, all of which are important in work and in life.

In the early years, educational institutions and the U.S. military used the new principles of OD. Academic programs were created to educate potential entrants into the field.

Reflections

So where does that leave the field of OD in the early 21st century?

Organization development has been defined by thought leaders in the field in a number of ways since its origin in the 1940s. According to Beckhard (1969), organization development is a planned, long-range change effort that utilizes behavioral science theory and research to develop key interventions that facilitate personal and organizational change.

French and Bell (1973) stated that OD was “a long-range effort to improve an organization problem-solving and renewal process, particularly in more effective and collaborative management or organizational culture—with special emphasis on culture of formal working—with the assistance of a change agent, or catalyst, and the use of the theory and technology of applied behavioral science, including action research (p. 15).” Inherent in this definition are several assumptions (Beckhard, 1969) concerning managerial values and the organization’s environment:

- Among the more important organizational goals are individual growth and development. Therefore, the organization strives to locate decision-making responsibilities as close to the source of information as possible and to give organizational members the opportunity for self-direction and self-control.

- Organizational members frequently engage in dysfunctional win-lose strategies. There is, however, the desire to establish more collaborative behaviors, characterized by trust, support, accurate communications, and joint problem solving.

- Personal feelings are legitimate indications of overall job satisfaction and need to be shared. Unspoken, these feelings can adversely affect the organizational climate and can result in interpersonal conflicts.

- Organizational members seek reference groups that, if used properly, can improve problem-solving effectiveness. Therefore, the organization wants to formalize these groups and to maximize their input.

- An organization is an open system, interdependent, with a constantly changing environment. Thus, to maintain/improve organizational performance, the organization must develop mechanisms for introspection, adaptation, and self-renewal.

- An organizational structure appropriate in the past may not be suitable for meeting present challenges.

In short, organization development impinges upon all aspects of organizational life—personal values, interpersonal and group relationships, management systems, and structures. None of this will change for the field in a VUCA world. What will change, in fact, must change, is the way the field looks at and defines planned, long-range change. As Heraclitus said, “Nothing is permanent but change.” And as Peter Vaill (1989) reminded us, the reality of organizational life is “permanent white water.”

Vaill wrote about the turbulence in organizations in Managing as a Performing Art (1989) and Learning as a Way of Being: Strategies for Survival in a World of Permanent White Water (1996). Among the challenges that Vaill described are many surprises, never-seen-before problems, and an unending and dizzying array of challenges and opportunities. “Permanent white water conditions raise the problem of recurrence,” along with the realization that “no number of anticipatory mechanisms can forestall the next surprising novel wave in the permanent white water” (1989, p. 1).

Organization development has been on notice for many years that the unpredictability of turbulent environments necessitates a cogent response. Now organizational contexts have been destabilized to the point that hardly anyone can assume that the basic structure or context will remain stable long enough to make a long-term course of action viable. And that’s the river into which OD must step to help organizations create a sustainable future.

In an article titled “Organization Development in the Future,” Halal (1974) stated that “predictions of the future are insightful, entertaining, and often hopelessly wrong. However, some extensions of present trends can be confidently made, especially if we restrict ourselves to the fairly near future” (p. 35). Some trends have been visible for some time, including larger organizations, flatter organization structures, more complex technology, and increased dispersion of organizations over wider geographic areas. The increasing size, complexity, and formality of organizations seem to exacerbate human and social problems. Because of these trends, it seems likely that OD will be needed in the future as much as it has been for the past seventy years.

The future of the field is closely connected to its response to VUCA. OD practitioners can help clients find an approach that embraces the underlying values and philosophy of organization development to deal with the VUCA environment.

But first, practitioners must acknowledge and reconcile the different approaches to OD. The current thinking tends to be based on the foundational pillars. Among those ideas is the belief that scientific positivism reveals a single transcendent truth that can be analyzed and changed using scientific methods. There is also the belief that small groups and organizations should continue to set and reinforce norms and attitudes regarding behavior.

Looking at what is driving the change produces a picture of the future. Terms we use today, such as agile, customer-driven, fast, flexible, global, networked, team, and knowledge-based, will be the drivers for the future workplace. New concepts will have a dramatic impact on how we work. Consider the following highly probable scenarios:

“Organizations of the future will be niche oriented, very lean organizations containing mainly those individuals who have the knowledge, skills, and ability required specifically for the organization’s niche. Other jobs not tied directly to the product or service will be outsourced. Traditional departments such as human resources, accounting, information technology, public relations, and logistics will no longer be part of a manufacturing company. Banks will only hire finance people; stores will only hire salespeople; trucking companies, only drivers; and airlines only pilots. Most if not all the support functions will be outsourced.” (Ingbretsen, 2013)

Small to mid-size organizations will be formed to provide services being outsourced by the niche-driven organizations. In many ways everyone benefits from this scenario. Outsourcing eliminates the challenge of recruiting, hiring, training, and retaining a large workforce not specifically dedicated to the product or service offered by the organization.

The new smaller, agile, and focused organizations will be a more acceptable fit for the sixty-five-million members of Generation Y as they assimilate into the workforce. Generation Y, also called Millennials or Echo Boomers, born between 1980 and 1995, see work through a very different set of lenses than do previous generations. Attempting to fit them into organizational boxes will not work. Organizations must provide challenging, fast-paced, and meaningful experiences for this new generation. This, too, is part of the new normal.

Consider also the emergence of social constructionist thinking that there is more than one truth and that multiple voices must be heard to discern what is or may be occurring within organizations. Some OD practitioners adhere to the belief that “multiple truths” can be discerned through such practices as appreciative inquiry, large systems change events, and other processes that “get all of the right voices in the room.”

The good news is that there continues to be a recognition of the basic humanistic values and philosophy promulgated by Abraham Maslow (hierarchy of needs), Douglas McGregor (theory X and theory Y), and Carl Rogers (the unconditional positive regard of each individual). The humanistic philosophy continues to be recognized in the democratic principles of Kurt Lewin (1948) and the client-centered process consulting action research approaches (Schein, 1969) of the 1960s and 1970s.

OD continues to be a powerful and institutionalized activity, and it significantly influences how organizations are managed (Kleiner, 1996). On the other hand, OD as a field continues to struggle with its own identity. It is often confused with change management and other forms of organizational change, its professional associations are grappling with their images, and many potential clients question the value of OD. The critical question posited by Worley and McCloskey (2006) in the first edition of this handbook was “What does the future of OD look like, and how will it get there?” The VUCA environment faced by organizations today makes this question even more critical.

Conclusion

VUCA presents a singular opportunity to engage organizations differently than has been done before. Because the need for adaptation is ever present because of permanent white water, the field has the opportunity to create an environment in which everyone participates in creating a culture of learners, and leaders and key decision-makers are not the only ones who set the course for the future.

Innovation and change processes often begin with a meeting. These meetings take place thousands of times each day across the globe. Leadership convenes a small group of people to help them determine the environment they need in order to become more successful. OD practitioners can be helpful in facilitating dialogue within and among the groups that carry this charter. This is an opportunity to bring many more people within an organization into such discussions.

The discussions often gravitate toward the transformative questions: What doors open for us if we make innovation a priority? What shape do our working lives take on with our co-workers and our customers as we engage with one another in more innovative ways? At some point, though, the group touches on the more sober subject of accountability: Who do we expect to participate in the process as it becomes more open and accessible? Should I make innovation and change part of my day job? Will the organization penalize me if I don’t participate? The subtext here is always “but I already have a day job with its own allotment of many sticks and few carrots.”

The volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity inherent in today’s world is the “new normal,” and it is profoundly changing how organizations of all kinds do business. It will also have a significant impact on how organization development practitioners interact with clients. The skills and abilities that were once needed to help organizations thrive are no longer sufficient. Today, more strategic, complex critical thinking skills are required, which means that OD practitioners must develop and display expert critical thinking skills in order to help client systems navigate in a VUCA world. Only by stepping into the river and engaging the current will we be able to counter volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity with vision, understanding, clarity, and agility.

References

Apollo Research Institute staff. (2012, March). The VUCA world: From building for strength to building for resiliency. Apollo Research Institute. Retrieved from http://apolloresearchinstitute.com/sites/default/files/future-of-work-report-the-vuca-world.pdf

Beckhard, R. (1969). Organization development: Strategies and models. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Boston Consulting Group. (2013). The most adaptive companies 2012. Bcg.perspectives. Retrieved from https://www.bcgperspectives.com/content/articles/corporate_strategy_portfolio_management_future_of_strategy_most_adaptive_companies_2012/.

Caron, D. (2009, February 8). It’s a VUCA world. CIPS. Retrieved from www.slideshare.net/dcaron/its-a-vuca-world-cips-cio-march-5–2009-draft

Crandall, N. F., & Wallace, M. J., Jr. (1995). Moving toward the virtual workplace. In H. Risher & C. Fay (Eds.), The performance imperative: Strategies for enhancing workforce effectiveness (pp. 99–120). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Dan, A.(2012, October 14). In a VUCA world, Unilever bets on “sustainable living” as a transformative business model. Forbes. Retrieved from www.forbes.com/sites/avidan/2012/10/14/in-a-vuca-world-unilever-bets-on-sustainable-living-as-a-transformative-business-model/

French, W. L., & Bell, C. (1973). Organization development: Behavioral science interventions for organization improvement. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Friedman, T. (2005). The world is flat. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

Halal, W. (1974, Spring). Organization development in the future. California Management Review, 16(3), 35–41.

Helgesen, S. (1999). Dissolving boundaries in the era of knowledge and custom work. In F. Hesselbein, M. Goldsmith, & I. Somerville (Eds.), Leading beyond the walls (pp. 49–56). San Francisco. CA: Jossey-Bass.

Horney, N., Pasmore, B., & O’Shea, T. (2010). Leadership agility: A business imperative for a VUCA world. People & Strategy, 33(4).

Ingbretsen, R. (2013). Organization development: The future workplace. Retrieved from www.ingbretsen.com/print.php?id=109

Johansen, B. (2007). Get there early. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler.

Kail, E. (2010, December 3). Leading effectively in a VUCA environment: C is for complexity. HBR Blog Network. Retrieved from http://blogs.hbr.org/frontline-leadership/2010/12/leading-effectively-in-a-vuca.html

Kail, E. (2011, January 6). Leading effectively in a VUCA environment: C is for complexity. HBR Blog Network. Retrieved from http://blogs.hbr.org/frontline-leadership/2011/01/leading-effectively-in-a-vuca-1.html

Kinsinger, P., & Walch, K. (2012, July 9). Living and leading in a VUCA world. Thunderbird University. Retrieved from http://knowledgenetwork.thunderbird.edu/research/2012/07/09/kinsinger-walch-vuca/

Kleiner, A. (1996). The age of heretics. New York: Doubleday.

Lawler, E. E., III. (1992). The ultimate advantage: Creating the high-involvement organization. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Lewin, K. (1948). Resolving social conflicts. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Margulies, N., & Raia, A. (1972). Organization development: Values, process, and technology. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Reeves, M., & Love, C. (2012, August 21). The most adaptive companies 2012. BCG Perspectives. Retrieved from www.bcgperspectives.com/content/articles/corporate_strategy_portfolio_management_future_of_strategy_most_adaptive_companies_2012/

Schein, E. H. (1969). Process consultation: Its role in organizational development. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Sullivan, J. (2012a). VUCA: The new normal for talent management and workforce planning. Ere.net. Retrieved from www.ere.net/2012/01/16/vuca-the-new-normal-for-talent-management-and-workforce-planning/

Sullivan, J. (2012b). Talent strategies for a turbulent VUCA world—shifting to an adaptive approach.Ere.net. Retrieved from www.ere.net/2012/10/22/talent-strategies-for-a-turbulent-VUCA-world-shifting-to-an-adaptive-approach/

Vaill, P. (1989). Managing as a performing art: New ideas for a world of chaotic change. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Vaill, P. (1996). Learning as a way of being: Strategies for survival in a world of permanent white water. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Worley, C. G., & McCloskey, A. (2006). A positive vision of OD’s future. In B. B. Jones & M. Brazzel (Eds.), The NTL handbook of organization development and change: Principles, practices, and perspectives. San Francisco, CA: Pfeiffer.