Chapter 5

Strategy and Capability

‘He who would learn to fly one day must first learn to stand and walk and run and climb and dance; one cannot fly into flying.’

Friedrich Nietzsche

On October 21, 1805, the British fleet met the French and Spanish fleet off the Cape of Trafalgar. The ships were similarly built and armed. The early nineteenth-century ship-of-the-line was a formidable war machine, consisting of 100,000 square feet of timber, 74 cannons (equivalent to the entire artillery force of most land armies), 600 to 700 men and boys. While they shared the same fighting platform, the British fleet was otherwise out-numbered, out-manned and out-gunned, with six fewer ships than the Franco-Spanish fleet, and considerably fewer soldiers. Yet, by the end of the day, the French and the Spanish had lost two thirds of their fleet, and suffered ten times as many casualties as the British. There are many historical reasons why this happened, but there are three that are of particular relevance to this book: strategy, capability and talent management.

From a talent perspective, the officer corps of the Spanish and French fleets was narrowly restricted to members of the aristocracy. In Bourbon France recruitment was limited to the elite trainee cadre of the Gardes de la Marine, educated on land in an essentially theoretical MBA-style curriculum. They studied hydrography and learnt how to fence, but regarded the practical skills involved in sailing a ship as well below their pay grade. Likewise, the captains of Spanish ships primarily regarded themselves as sea-bound, army officers (the mark of true nobility), delegating seamanship and the transportation of their infantry and artillerymen into position to a junior officer, or pilot. In contrast, British naval officers were recruited from a much broader range of social backgrounds, including the sons of merchants, lawyers and vicars (like Nelson). While influence and patronage were always a factor in securing promotion, experience and genuine ability remained the decisive factor. The test to become a junior officer in the British navy depended on having spent at least six years at sea, and the ability to pass a rigorous practical examination.

In Men of Honour (2005),1 his highly insightful book on the men who fought at Trafalgar, Adam Nicholson summarizes the difference between the British, French and Spanish officer corps as follows:

‘For an aristocrat, failure in battle does not erode his standing or his honour. He remains, as long as he has behaved with courage, the man he was born to be. For the younger son of the English gentry, or lawyer or merchant, as most British officers were, there is no such destined luxury. If he fails at sea, his standing is diminished; he has not won the prize money which will set him up at home; his name is not gilded with honour; he has failed in the same way that a failing entrepreneur has failed. To preserve his honour and his name, he needs to win. Victory is neither a luxury nor an ornament. It is a compulsion and a necessity.’

From a front-line perspective it can also be said that the training afforded the British able seaman and gun crews was far superior to their French and Spanish counterparts. From 1745 every ship in the British navy had been obliged to perform gunnery practice every day. The best captains chose to practise in bad weather, to ensure their seven-man gun crews could operate just as ably when the ship was pitching and rolling. These gun drills were timed and measured and rates of fire steadily improved. By the Battle of Trafalgar most British gun crews could manage a round every 90 seconds, three times fast than the average Spanish crew. As Ben Wilson explains in his book Empire of the Deep (2013):2

‘The foundation of British naval might was the discipline, order and teamwork shown by thousands of highly trained seamen. Speed of manoeuvre, rate of fire and determination in battle all depended on these qualities.’

The British Navy's success was founded on these differentiating talent capabilities, but the determining factor at Trafalgar was strategy and leadership. The most basic explanation of strategy is the application of strength against weakness, and in these terms Trafalgar was a strategic masterclass. In order to maximize his fleet's distinctive advantages in sailing ability and rate of fire, Nelson chose not to take the conventional course of fighting in parallel with the combined French and Spanish fleet. He divided his fleet into two columns and drove them into the enemy fleet at right angles. Furthermore, he trusted his captains to make their own decisions once the battle commenced. In breaking the coherence of the Franco-Spanish fleet Nelson also broke its chain of command. He made it more difficult for them to sail and manoeuvre, and he brought his highly trained gun crews into close quarters where their superior rate of fire could inflict most damage.

As Richard Rumelt points out in Good Strategy, Bad Strategy (2011), ‘Good strategy almost always looks this simple and obvious and does not take a thick deck of PowerPoint slides to explain’.3 Effective strategy identifies one or two critical challenges, the pivot points where strength meets weakness or opportunity, and then coordinates and focuses action and resources on them. Whether business strategy, HR strategy or employer brand strategy, the same principles apply.

While the main focus of this book is employer brand strategy, the principle of coordinated action is highly relevant to final success. Just as an employer brand should work within the brand hierarchy, it should also work within the strategic hierarchy. The employer brand strategy needs to be fit for purpose, and this purpose necessarily includes the organization's overall business strategy.

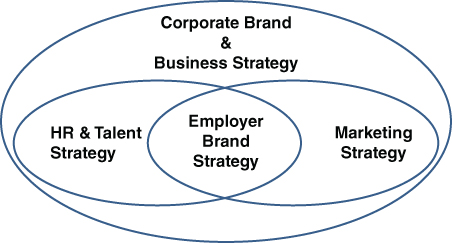

There are many ways of representing the potential layers within a corporate strategy, but I suggest the following as a simple point of reference for this book (Figure 5.1).

Figure 5.1 Integrated strategy model.

This representation places employer brand strategy mid-way between the people management strategy and the marketing strategy, and directly beneath the corporate/business strategy. This is because employer brand strategy needs to align with all three. It needs to support the kind of talent capabilities required for the organization to compete effectively. It needs to align with the way that HR and talent management operates within the organization. It also needs to reflect the corporate and customer brand promises and ambitions of the company. Ideally, line management, HR management and marketing management should be in complete alignment, but we live in an imperfect world. For this reason, employer brand strategy is often required to play a reconciliatory role between these different stakeholder groups to help maximize the effectiveness and coherence of all three.

CORPORATE STRATEGY

In a company operating a single business, this may double as the business strategy, but for more diverse ‘businesses’, the corporate strategy should determine the organization's overall scope and objectives. The key questions at this level are: ‘What do we believe in? (purpose and values) and what businesses should we be in?’ (business portfolio).

BUSINESS STRATEGY

The business strategy should determine where and how an organization can best compete in the marketplace. P&G's CEO, A.G. Lafley, suggests the two key business strategy questions are: ‘Where should we play? And how can we win?’4

Both questions require significant insight and foresight into the organization's current and potential capabilities in relation to customer needs and the competitive context. Answering the capability question and the competitive question are key to a successful strategy. In too many cases, business strategies appear to be no more than a wish-list of desired objectives, without a clear identification of the key challenges, or the choices made to overcome them.

The first major choice is whether the organization should compete on cost or differentiation. A cost-based strategy inevitably focuses the efforts of the company on operational efficiency, seeking to gain and sustain competitive advantage by offering the same products and services for less. A strategy based on differentiation takes the opposite course, focusing effort on innovation and added value, seeking competitive advantage by offering customers something they can't buy anywhere else. While there is always some interplay between these two approaches (differentiation still needs to be competitively priced), it's very difficult to follow both courses simultaneously. In most cases, you need to make a choice.

If your organization is taking the second course, which is overwhelmingly the favoured option among leading brand-focused companies, you need to be very clear about the resources and capabilities you require to build and sustain your competitive advantage.

Since the term was introduced to the business and HR lexicon in the 1990s there have been many different definitions of the term ‘capability’. For the sake of the arguments made in this book I suggest the following frame of reference (Table 5.1).5

Table 5.1 Organizational capabilities

| Resources Tangible and intangible organizational assets. |

Competences The skills and abilities by which resources are effectively deployed. |

|

| Threshold capabilities | Threshold resources Meeting operational requirements and customer expectations Tangible: the physical assets of the organization like buildings, people, technology and finance Intangible: Information, knowledge and reputation (Intellectual capital). |

Threshold competences Generic activities and processes within HR, marketing, finance, IT and other key functions needed to meet basic operational requirements and customer expectations. The most fundamental example is cost efficiency. |

| Capabilities for competitive advantage | Unique resources Underpinning competitive advantage because others find them more difficult to obtain or imitate (including a strongly differentiated brand reputation and culture). |

Core competences Differentiating activities and processes that deliver a unique value to the organization, business and customers. |

| Dynamic capabilities | Flexible resources Underpinning the organization's ability to change, for example liquid assets, or a flexible pool of part-time and temporary workers. |

Transformative competences Activities that enable the organization to learn, adapt and change. |

Note: Adapted from Johnson et al (2008) Exploring Corporate Strategy3

Maintaining competitive advantage relies on identifying capabilities that are both durable and difficult to copy. Sustainable advantage seldom rests in individual capabilities, but in how they combine together. Michael Porter calls this an ‘activity system’.6 He writes that ‘competitive strategy is about being different … [which] means deliberately choosing a different set of activities to deliver unique value’. In addition to being different from the activity systems of competitors, it's also important for these capabilities to mutually reinforce one another. The inter-linked complexity of these systems is often very difficult for competitors to copy. Over time, they tend to become embedded in the culture of an organization in ways that it is difficult for even its own managers to fully understand. This can become dangerous, because however important strategic capabilities may be at a particular time, they also need to be renewed and recreated in response to changing customer needs and market contexts. In the hyper-dynamic and competitive environments in which many organizations operate, this means that an absolutely key competence has become the ability to learn, adapt and change. This in turn means that organizations should be clear about which capabilities and activities are the most important in maintaining their current competitive advantage, as well as those which they may need to strengthen or acquire moving forwards.

In A.G. Lafley's book Playing to Win, he describes the five core capabilities that ‘set P&G apart’.

- Deep Consumer Understanding. This is the ability to truly know shoppers and end users. The goal is to uncover the unarticulated needs of consumers, to know consumers better than any competitors do, and to see opportunities before they are obvious to others.

- Innovation. Innovation is P&G's lifeblood. P&G seeks to translate deep understanding of consumer needs into new and continuously improved products. Innovation efforts may be applied to the product, to the packaging, to the way P&G serves its consumers and works with its trade customers, or even to its business models, core capabilities and management systems.

- Brand Building. Branding has long been one of P&G's strongest capabilities. By better defining and distilling a brand building heuristic, P&G can train and develop brand leaders and marketers in this discipline effectively and efficiently.

- Go-to-Market Ability. This capability concerns channel and consumer relationships. P&G thrives on reaching its customers and consumers at the right time, in the right place, in the right way. By investing in unique partnerships with retailers, P&G can create new and breakthrough go-to-market strategies that allow it to deliver more value to consumers in store and to retailers throughout the supply chain.

- Global Scale. P&G is a global, multi-category company. Rather than operate in distinct silos, its categories can increase the power of the whole by hiring together, learning together, buying together, researching and testing together, and going to market together.

Lafley stresses the importance of the system over the individual parts. ‘In isolation, each capability is strong, but insufficient to generate true competitive advantage over the long term. Rather the way all of them work together and reinforce each other is what generates our enduring advantage. That combination is hard for competitors to match.’ Most organizations don't do this. Rather they pursue multiple objectives that are unconnected with one another, or worse, that conflict with one another. Complex organizations tend to spread rather than concentrate resources in order to placate many different stakeholders. Focus reveals strategy and leadership at work.

HR STRATEGY

Many of the ways that HR supports the business relate to threshold competences. For the business to operate effectively employees need to be recruited, engaged, developed, deployed, performance managed and rewarded. HR plays a major role in ensuring the systems and processes are in place and operating as efficiently and effectively as possible. Establishing a professional HR management system within an organization is seldom an easy task, and in many cases the HR ‘strategy’ will simply be focused on implementing or incrementally upgrading these basic competences. As the business changes course, as it is frequently required to do, HR also plays a role in adjusting and re-aligning these HR processes and systems to fit with the latest requirements.

When developing an employer brand strategy it's essential to understand these go-forward HR plans and priorities as they can potentially have a significant impact on employee experience as well as organizational effectiveness. Typical priorities might include:

- Upgrading HR information systems.

- Moving towards a self-service model for basic HR transactions.

- Introducing a new performance management system.

- Improving access to training though e-learning.

- Implementing a new career-path model.

- Promoting career mobility through open job posting.

- Increasing bench-strength though more disciplined succession planning.

Every one of these steps is likely to improve operational effectiveness and impact on the performance of the business if implemented successfully. However, none of them in isolation is likely to provide or underpin a decisive competitive advantage. Given the speed of change there may be an argument to suggest that all you need to do to compete is adopt and adapt new people management processes and technologies before anyone else. The management guru, Peter Senge, famously claimed that the only sustainable competitive advantage is the ability to learn faster than your competition.7 However, there is a great danger that this constant round of change activity will be counterproductive. Firstly, it always takes time to absorb new approaches. Continuous change can result in a constant drag on the organization, undermining operational efficiency and organizational effectiveness rather than improving it. Secondly, not every new development in HR is going to work for every company. As JTI's global HR Director, Jorg Schappei, describes it:

‘There needs to be a good balance between best practice and best fit. There is no one size fits all. If P&G does certain things it might be considered best practice, but it might not fit every company. The culture may be different, the politics may be different and the leadership style may be different. Best practice is not always transferable. The HR world is full of buzz words. Every 6 months something new pops up, and I think many HR functions make the mistake of doing something new just for the sake of making change, to create the appearance that they are on top of things, and not behind the curve.’

HR is also criticized for its lack of coherence, and one of the major fault-lines runs straight down the middle of employer brand management. As Martin Moerle, the Global Head of Talent at UBS, puts it:

‘HR tends to be a collection of independent processes rather than an integrated suite of people management services. It's easier to run thing separately rather than manage a complex web of inter-dependencies, but this fragmentation is sub-optimal in terms of supporting business performance. One of the most significant divisions lies between those who bring people in and those who cultivate people once they've joined the organization. This is a missing link which the integrated talent approach might begin to close. Bringing these different elements together is vitally important if you want to build a strong employer brand.’

Finally, a long HR initiative wish-list will also distract the team from making more focused choices about the kind of capability-building actions the business needs to make to support a more differentiated market positioning and long term sustainable advantage. For this kind of game-changing capability, HR needs to apply itself to the more complex, organizational ‘activity-systems’ that support competences like:

- Market insight and foresight.

- Continuous improvement.

- Breakthrough innovation.

- Cross-functional collaboration.

- Speed and agility.

- Customer empathy and responsiveness.

These represent a different category of capability to the more process-specific competences relating to recruitment, development, performance management and reward. Firstly, they require a more systemic approach. In other words, if they are to be honed to a competitive edge, these capabilities may require changes to every aspect of one of the people management processes mentioned above. Secondly, this kind of distinctive capability generally requires trade-off choices to be made. You can improve the general efficiency and effectiveness of every HR process and it will generally support the business. However, past a certain threshold point, investment will need to follow the more specific ‘how to win’ plays the business is making. It may be possible over time to develop a portfolio of core competences that deliver unique competitive advantages, but it's virtually impossible to develop them all at once.

These questions and choices are critical in developing EVPs that are not only ‘fit for purpose’ in a general sense from a talent attraction and engagement perspective, but also fully aligned with the capability needs of the business. If the organization is driving for greater speed and agility (as Reuters were in their battle with Bloomberg at the beginning of the last decade) it makes sense for this strategic priority to be reflected in the ‘Living Fast’ employer brand positioning and pillars. Likewise, if breakthrough innovation is the lifeblood of the company, as it is for Philips, ‘Innovation and You’ makes for a perfect positioning.

TALENT STRATEGY

Over the last six years, CEOs have become increasingly worried about finding the right talent to drive future success. In the latest edition of PWC's Annual Global CEO Survey, 63% of participants expressed this concern (compared with 58% in 2013 and 53% in 2012), and 93% either expressed the need to change, or are currently changing their strategies for attracting and retaining talent.8 This reflects a growing realization that in today's knowledge and service driven economy, employees are increasingly the most critical corporate asset.

As Tom McCoy, the CEO of JTI, puts it:

‘Our employees play the big game, they are basically who we are. Our employees are the ones who most represent us out in society, they are the ones who apply the discipline required to deliver a quality product. Unless we attract the right kind of people, and get it right for our employees, living up to what we say we want to be, getting their buy-in, we can never get it right as a business.’

In this context, it is unsurprising that talent management has been increasingly recognized as one of the most vital components within the overall business strategy. Deloitte concludes from its Human Capital Trends Survey (2014) that top performing HR teams are currently the ones most focused on talent (particularly leadership, talent acquisition, engagement and analytics).9 There also clearly needs to be strong alignment between the employer brand strategy and the talent strategy. As David Henderson, Chief Talent Officer at Met Life, sees it:

‘The EVP needs to be interwoven into each strand of the talent management strategy – it sets out the philosophy and provides a lens through which specific initiatives can be viewed. The goal is to constantly reinforce the values and attributes of the EVP through the execution of the talent management strategy and in that sense you might even argue that EVP sits above the talent management strategy as a strategic driver.’

INCLUSIVE vs EXCLUSIVE TALENT MANAGEMENT

Talent strategy is variously defined in different organizations. In some it appears to be almost synonymous with HR strategy, in others it is more tightly restricted to the identification and development of the current and potential leadership population. The scope of ‘talent strategy’ within an organization tends to be closely linked to whether talent is defined in inclusive terms (every employee has talents) or more exclusively (the talented few that contribute greatest value to the business). You can argue the merits of both perspectives.

The inclusive talent perspective/talent management for all:

- Most employees have been through a selective hiring process to ensure they have the talent required to fulfil their role. Most employees, particularly those working for leading multinationals, are above average in terms of the general population and, in many cases, significantly above average.

- Every employee has ‘talents’ and the more these talents can be identified, developed and realized, the more employees will be able to contribute to the overall success of the organization.

- If everyone is recognized as having talent and potential, research suggests they are likely to perform better than if they are identified as second class citizens.

The exclusive talent perspective/talent management for the few:

- Top performing ‘talent’ within an organization contribute significantly more than average performers, and therefore deserve special attention.

- Top talent is also going to have greater opportunities outside the organization and therefore need priority treatment to ensure they are retained.

- Given that resources for development are always limited, it also makes sense to prioritize investment on top talent where it will deliver the highest return.

While these are generally seen as opposing approaches, there is no reason they cannot be applied simultaneously. There is surely a benefit in recognizing every employee has ‘talents’ that can be managed to maximize performance and developed to maximize potential. Likewise, it's equally important to recognize that some people will be more talented than others and require extra attention and investment as a result. From an employer brand perspective, an inclusive overall definition of talent provides greater scope for promising development opportunities for all, while still enabling more targeted investment and messaging for those regarded as ‘pivotal’ or ‘critical’ talent to business success. In contrast, the more exclusive (and divisive) the talent definition, the more limited you're likely to be in making EVP claims that applyto everyone.

BUY, BORROW OR BUILD?

Talent definitions aside, the second most important question from an employer brand perspective is whether the organization subscribes to a ‘build’, ‘buy’ or ‘borrow’ talent strategy. The ‘buy’ model puts a greater emphasis on hiring people with the right skills when you need them, rather than relying on internal development. This generally means hiring fewer recent graduates and more ‘experienced hires’. It also tends to lower levels of organizational identification and loyalty, and a correspondingly higher employee turnover rate.

The commercial argument made for a ‘buy’ strategy is:

- It reduces the spend required for training and development.

- It keeps the organization refreshed with ‘new blood’ and new ideas.

- It provides the organization with greater agility.

In some respects, the ‘borrow’ strategy is simply a more extreme form of this, where you ‘borrow’ talent (e.g. hire contingent labour, or partner with another company like an outsourcing provider to obtain the skills needed).

In contrast to ‘buy’ or ‘borrow’, the ‘build’ strategy puts greater emphasis on developing ‘home-grown’ talent. This generally means a more significant graduate programme, and a strong preference to promote from within. In many leading organizations, graduate hiring is also accompanied by a major investment in development and mobility, enabling new joiners to experience many different aspects of the organization, building a strong understanding of the business ‘as a whole’ and strong personal networks. BP, whose ‘Challenge Development Programme’ is widely recognized as one of the best graduate programmes around, is a strong believer in ‘build’ over ‘buy’. As Helmut Schuster, BP's Executive Vice President for HR, explained to me:

‘I think the whole switch from Company loyalty to employability is very misguided. I really believe that when you hire people directly from university they get a very good understanding of the business. They really understand the essence, the DNA of the organization. The problem is if you hire too many people in at a later stage they do not always fully understand the company and they do not always understand the unintended consequences of their decisions. That's why the build model complemented by targeted external hiring is much more powerful, but it also requires great consideration to make sure people do not become too insular, that they also get an external perspective. These are the risks you need to manage, but it's a risk I'd rather manage because it is easier to control.’

GLOBAL LOCAL STRATEGY

A major strategic challenge for most multinational businesses is striking the right balance between global control and local autonomy, which from an employer brand perspective translates into global consistency and local fit. Some international organizations are still operating a decentralized model, where talent related processes and practices remain highly localized. In this context, you may be developing an EVP for your local market or business unit with minimal interference (or support) from the centre. If this is the case, you can maximize your fit with local market needs, but it also makes sense for you to ‘steal with pride’ from other parts of the organization that may have already invested in creative ideas and assets that may be adapted to your needs at a far lower cost than if you act entirely independently.

Over the last decade, the more significant trend has been towards greater global standardization within HR and talent management, driven in part by efficiencies of scale (particularly in relation to new technology systems), but also a desire to establish more consistent global standards. This in turn has also been reflected in a heavy focus on global employer brand identities and campaign styles. If you're developing your employer strategy in this context, the focus generally needs to be on keeping things simple, easy to adopt, use and maintain. This context also requires a larger investment in training and monitoring, while local teams get used to working within the new brand framework.

Since most leading multinational companies have now developed a global employer brand, and the disciplines required to maintain a reasonable degree of consistency, their emphasis now appears to be shifting back to local fit. This does not mean a return to complete local brand autonomy, but more room to exercise local judgement and freedom within the global brand framework. This may mirror a similar shift in HR processes generally, with many multinational companies, having established common information systems and process frameworks, now placing more focus on local customization.10 This should represent a more ideal balance, maximizing the value of shared investments and coordinated brand building, while at the same time tailoring to local needs and preferences. If you're developing your employer brand strategy in this context, you will need to invest more in local validation and adaptation. You also need different skills and behaviours in your local teams, as creative imagination will become as important as brand discipline and control.

SUMMARY AND KEY CONCLUSIONS

- Business success depends on distinctive capabilities and a clear competitive strategy.

- The role of employer brand management is not just to attract and engage talented people, but to inject and reinforce the right kind of talent capabilities.

- The employer brands need to support the overall business strategy, and create a strong bridge between your HR/Talent Management and Marketing strategies.

- You need to clarify whether your organization is principally competing on cost or differentiation. Your life will be a lot more interesting if you're supporting the latter objective.

- While individual HR capabilities are important, superior and sustainable competitive advantage generally depends on the development of coherently designed and mutually supportive ‘activity systems’.

- You need to understand your HR forward plan to be able to identify where potential aspirational brand claims are most likely to be supported by future improvements in the employment offer and experience.

- You're more likely to make an effective impact on employment engagement and business performance with fewer and more focused people management initiatives than a constant influx of new HR tools and techniques.

- A generally inclusive approach to defining talent (talent management for all) need not negate your efforts to prioritize more exclusively defined talent groups. You can have it both ways.

- One of the most vital talent strategy inputs to your employer brand strategy is the emphasis the company is choosing to place on ‘buying’, ‘building’ or ‘borrowing talent’.

- The final context setter for your employer brand strategy is the relative balance and direction of global vs local control over people management and communication.