Chapter 11

EVP Development

‘Character is the tree, reputation is the shadow.’

Abraham Lincoln

Isaac Newton ushered in the rational enlightenment. He also believed in the philosopher's stone. He's best known for his science. He gave us laws of light and motion. He showed us how to predict the course of heavenly bodies, and explained the steady pull of gravity. As one biographer put it: ‘He made knowledge a thing of substance, quantitative and exact’.1 It was not until over 200 years after his death that a prominent economist, collecting and deciphering the apparently impenetrable trunks of manuscripts, also discovered Newton harboured a secret passion for alchemy. In complete contrast to his mechanistic theories and legacy, he also believed in the magical transformation of base metal into gold. As my previous boss and mentor, Mark Sherrington, pointed out, brand development is like alchemy.2 You need hard data and evidence, but you also need some magic to transform this base material into something that lifts the spirit and fires the imagination.

The principal role of the employee value proposition (EVP) is to provide a consistent platform for brand communication and experience management. In some cases an organization may choose to use an EVP to underpin a single communication campaign, but increasingly EVPs are designed to play a much wider role in providing brand integrity across all forms of brand communication and people management activities. In the global employer brand practice survey People in Business conducted in 2012, 60% of participants described employer brand development as a key component of their overall HR strategy, compared to 1 in 5 describing it solely in terms of resourcing.3.

As Simon Riis-Hanson, Senior Vice President of HR at the LEGO Group, puts it:

‘What our People Promise [EVP] has done is provide us with a compass that can guide us in multiple ways from our strategic direction to our everyday decision making and it is something you can see present all the way from our HR processes to the way we manage our value creation within the business to the way we communicate as leaders in the company every single day. You can find it has coloured everything we do as a company. It's been woven into the fabric of how we do things.’

Where an EVP is seen mainly as a platform for a recruitment campaign, it's generally sufficient to define the proposition in terms of a short paragraph which aims to capture the essence of the employment offer, and/or a number of core communication themes.

A typical example from the pharmaceutical distributor and healthcare information technology company, McKesson Healthcare, reads:

‘At McKesson, I not only connect with the organization's mission to advance healthcare, I am proud of the way our company conducts business–insisting on integrity and living by a set of values that guide our day-to-day activities. I join my colleagues in a concerted effort to improve lives by delivering high value to our customers, immersed in an environment that is challenging, engaging and entrepreneurial. My professional goals and personal fulfilment are more attainable because of McKesson's unquestioned leadership position, distinct tradition of performance and expansive scope.’

Written from the point of view of the candidate or employee, this kind of positioning statement is not designed to be used directly for advertising copy, but to define the desired response, and in doing so, provide a consistent point of reference for the development and articulation of all employment marketing communications.

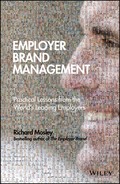

For the purposes of this chapter I am going to assume a wider remit for the EVP since this involves the greatest complexity and it's easier to pare back if the objectives are narrower. In this case, the most common practice is to define a number of EVP pillars, in addition to an overall positioning and proposition statement.

The core positioning can be defined as:

- The compelling essence or heart of your proposition.

- The one thing you most want to be famous for as an employer.

- The quality or idea you will build your employer brand story around.

The role of the pillars is to provide a consistent reference point and linking mechanism for:

- Building the employer brand image and reputation – the key qualities the organization wishes to be associated with as an employer.

- Defining the employment deal – the key benefits that employees can expect from employment with the organization, balanced with what is expected of them in return.

- Determining the key employer brand communication themes.

- Shaping the employer brand experience – the key priorities for people management policies and practices.

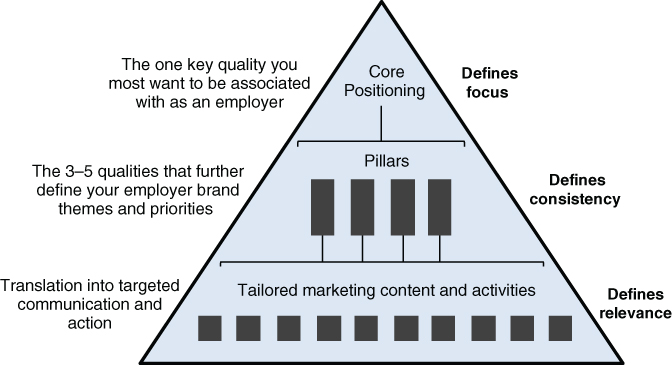

This platform (Figure 11.1) is not designed to replace other common formulations of the employment deal, like Total Reward policies, but to supplement them with a more focused list of key priorities. Towers Watson sees the portfolio of talent and compensation programmes that make up ‘Total Reward’ as playing a key role in supporting a company's EVP, as follows (Figure 11.2):

Figure 11.1 Key components of the employer brand platform.

Figure 11.2 Total Reward Model (Towers Watson).

Drawing on the experience of leading around 50 different EVP development projects over the last ten years, and less direct involvement in numerous others developed by People in Business and TMP Worldwide, I would recommend the following steps.

ESTABLISHING A STRONG FOUNDATION

(a) Selecting the right development team

The first fundamental lesson of effective employer brand development is that it pays to involve a wide range of stakeholders. The core development team, or steering group as it is sometimes called, should include representatives from HR, Talent Management and Resourcing, Marketing and Communications, and where possible, line management. The inclusion of line managers in the core team is qualified because it tends to be less related to their core function.Involvement in the process can generally be achieved through less time intensive stakeholder interviews, EVP development workshops, validation meetings and sign-off presentations.

Most of the EVP development projects we have been involved in have been led by HR with the support of the corporate brand team, marketing and communications, rather than the other way round. This makes sense from our perspective. While they tend to have less brand management experience, HR ultimately has accountability for most of the processes that shape the employer brand experience. Our benchmarking survey revealed that 60% of projects are sponsored by the most senior HR leader and 30% by the head of talent management or organizational development.4

In a global EVP development project, early regional representation is also a critical factor in both getting to the right proposition and ensuring local management acceptance. The recent global EVP development project for Santander was jointly led by managers from three of the countries within the group: Spain, Brazil and Argentina. This reflected the importance of these markets in terms of employee numbers, but also the leadership each of these respective countries had already demonstrated in people management and communication.

As Viviane De Paula, Santander's HR lead in Brazil explains:

‘Co-creation was a key success factor. Our global HR leadership team defined six key projects to take HR to the next level at Santander, but rather than assuming all of the new thinking would emerge from the centre, they looked at best practices globally, and chose three different centres to lead each one. For the employer brand development project this included Brazil, as we'd already conducted some advanced work in this area. It also included Argentina, where Santander has been recognized as Best Employer for many years, and our employee engagement practices are extremely good. Together, with Santander in Spain, we took the lead on developing the new global EVP, with input at various points from six of our other major markets. This ensured a more balanced global perspective throughout and a much higher level of local ownership and commitment to the final result.’

Sometimes it can be valuable to hold a number of different EVP development workshops in different markets and then bring all of the findings together in one final global workshop. Pepsico took this approach, running a workshop in Thailand with participants from their key emerging markets, India, China and Russia; a workshop in London, bringing together a number of their key European managers; and then finally a workshop in the USA, to pull it all together. Lafarge, the French building materials giant, adopted a similar approach conducting development workshops in their key emerging markets of China, India and Egypt before running a final global workshop with representation from a much wider range of markets in Paris.

(b) Consultation with executive management

If your objective is to develop an EVP that will not only shape your external reputation as an employer, but also shape the organization's overall approach to people management, it will require active commitment from the senior leadership team. Out of the 271 participants completing our benchmark practice survey, the vast majority (77%) claimed to have consulted with their executive management team.3 The first step is to clarify the leadership's organizational development and talent agenda. Unless they have already been explicitly defined, the key questions to address are:

- What organizational capabilities are perceived to be critical to the company's future success? (These might relate to general operational effectiveness, or potential areas of competitive differentiation.)

- What, if any, organizational changes are being planned to reinforce and build these capabilities? (These might include global expansion, re-branding, re-structuring, process re-engineering and/or the adoption of transformative technologies.)

- What aspirations do the leadership team share in relation to the culture and reputation of the organization? (These might include the shift towards a high performance culture or the desire to be recognized as the leading employer of choice in your industry sector.)

(c) Consultation with the HR leadership team

In addition to the questions above, which should be equally relevant and clear to the HR leadership team, it's important to establish the current HR priorities that exist within this broader organizational context.

- What talent challenges currently or potentially stand in the way of realizing desired organizational capabilities? (These might include attraction, engagement, development, succession planning, deployment and retention.)

- What changes or upgrades are being planned to HR policies and processes that need to be taken into consideration when developing the EVP? Of particular relevance are investments in HR technology, resourcing, on-boarding, performance management, learning and development, total reward and talent management, as these may provide important additional benefits to current and potential employees, as well as potential opportunities for the employer brand team to embed new ways of thinking.

(d) Consultation with the brand team

As outlined in Chapter 4, it's of vital importance to ensure the employer brand is effectively aligned with corporate and customer brands. It is therefore critical for the employer brand development team to either directly involve or consult with the relevant brand authorities within the organization to clarify both the parameters within which the employer brand needs to work and the opportunities for potential synergies and leverage.

- What is the current or planned customer brand proposition? Is it of particular importance to identify the brand personality and service style?

- What are the most important points of differentiation (for example, cost efficiency, speed, expertise, empathy, fun)?

(e) Agency support

At some point during this process of project activation and consultation, you need to establish what kind of external support you may need. Employer brand development could potentially benefit from a wide range of specialist skills, including internal and external research, proposition development, creative expression, recruitment communication and internal brand engagement.

The first question to ask is whether you need or can afford to invest in external agency support. Most leading employers contemplating a major employer brand development exercise choose to invest in external support for the following reasons:

- It provides specialist expertise and experience that may not currently exist within the organization (helping to avoid dangerous pitfalls, draw on best practice and both support and up-skill the company managers involved in the project).

- It helps provide the short term boost to internal resources often required to deliver an intensive project while maintaining ‘business as usual’.

The second question to consider is what kind of agency or agencies you most need.

Marketing and communication managers managing corporate and customer brands typically draw on a range of different agencies for support in relation to:

- Market research

- Product and service development

- Brand identity and design

- Advertising

- PR

- Direct marketing

- Digital/‘web’ development

- Internal marketing, communication and engagement.

The pattern is not so dissimilar within HR, though they tend to choose more specialized services for:

- Employee research

- Recruitment advertising/search and selection

- Employee communication

- Training

- Reward.

There are some advantages in approaching one of the agencies that is already being used by your marketing and communication teams for employer brand related creative development. They should already be familiar with the workings of the corporate and/or customer brand. They may be able to help in building a stronger bridge between the HR/Talent/Resourcing team and the Marketing/Communications team. There are also some potential disadvantages. The experience and expertise required for effective development in the employer brand marketing field is often quite different to that required for corporate and customer marketing, both conceptually and stylistically. Where the agency relationship is dominated by the needs of the corporate/customer brand, the employer brand can also end up being treated like a ‘poor relative’ and not receive the creative time, attention and quality resource required for success.

The alternative is to approach an agency with proven employer brand development and recruitment marketing credentials, the advantages of which are:

- Authority with senior managers (particularly if similar projects have been delivered successfully for companies that are admired within the leadership team).

- A deeper understanding of the EVP and wider employer brand strategy (there are clear benefits in developing this creative platform within the same agency that develops the underlying EVP).

- Specialist experience and expertise in identifying the kind of creative approaches that work in attracting and engaging talent (vs consumers and investors).

(f) Establishing the business case and securing leadership support

Having established the strategic context, the next step is to find the best way of supporting and, in some cases, constructively challenging the above agendas, through a draft employer brand plan and business case. As detailed in Chapter 2, this should clarify your development objectives, project scope, planned investment, required leadership support and expected return.

(g) Review your existing data and insights

Most organizations have a wide range of existing data points from which they can draw relevant employer brand insights. These might include:

- External reputation and attraction research

- Competitor analysis

- New joiner surveys

- Employee engagement surveys, exit surveys, and focus groups.

Once this data has been collected together, you should evaluate whether there are any important gaps to fill, before moving onto the proposition development work.

The biggest gap is often qualitative research data. While engagement survey data may give you an indication of your relative strengths and weaknesses from a people management perspective, it seldom provides the necessary cultural insight required to build a distinctive employer brand proposition. The key decision to make at this point is whether you invest in conducting explorative qualitative research in advance to feed your proposition development, or after, to validate, refine and tailor your EVP to local audiences. If you have a large research budget you may be able to do both, but in most cases you need to make a choice. The advantage of exploratory focus group research is that it provides a richer and more stimulating source of insight for EVP development than simply working with the numbers. The advantage of creating a draft EVP first and then testing it is that you get a much more focused feel for what will work at the local level (including potential creative options as well as pillars). Where budget is limited we have generally found the former approach works better when you're more focused on creating a purely communications driven solution, and the latter approach is more effective when you're attempting to develop a more integrated solution.

(h) Building an insight platform

Once you've collected your data, it's important to identify the key insights and translate them into a format that's easy for people to digest. Table 11.1 provides a potential structure for this high level review.

Table 11.1 Employer brand insight platform

| Employer brand objectives | What are we trying to achieve? (scope/scale) What are the brand parameters? (corporate brand/core values) What are our priorities? (attraction/engagement/retention) |

| Key target audiences | Who do we most want our employer brand to appeal to? How much variation do we need to account for among target groups? |

| Current external reputation | How familiar are people with our organization? How are we currently seen in terms of image and reputation? How accurate are these perceptions? What is our relative position to key talent competitors? How (if at all) are we perceived to be different? |

| Current employee experience | What are our current levels of employee engagement and advocacy? How are we rated as an employer by our current employees? How do our scores compare with key talent competitors? How much variation is there between different parts of the business? |

| Attraction and engagementdrivers | What most attracts our target audiences to a new employer? What are the key factors driving employee engagement and retention? |

| Organizational capability needs | What key capabilities does the organization need to reinforce and build? What other aspirations do leadership have for our employer brand? |

EVP DEVELOPMENT WORKSHOPS

EVP development benefits from specialist expertise and experience, but it generally works best as a collective exercise. There are two key reasons for this. The first is that strong EVPs need to balance a number of different perspectives, and this is more effectively accomplished when there are a diverse range of people involved rather than a narrow functional perspective. The second important reason is that the ultimate success of the exercise relies on the understanding and commitment of a wide range of different stakeholders. Since brand development is something that few people outside the marketing department may have been involved in, it's very beneficial for key stakeholders from a number of different functions and positions to be directly involved in co-creating the EVP. This helps them to reach a far better understanding of the brand development process, and as a co-creator of the EVP they are also far more likely to champion the end result.

My recommendation would be to position the workshop as a brain-storming exercise, exploring the research findings, generating options, with the aim of reaching an 80% solution rather than a complete final conclusion. Ideally, by the end of the workshop, you should have identified a shortlist of potential EVP ingredients supported by key insights; the ‘give and the get’ of the implied employment deal; key areas of current strength and future stretch; points of parity and difference with your leading talent competitors; your desired brand personality; and a number of potential core positioning options.

I suggest a full day for this kind of workshop, and if there are a large number of people from different markets a second day may also be required to reach an effective conclusion. We generally structure our workshop around the following key elements.

(a) Employer brand briefing

This is designed to provide everyone with a thorough understanding of the context, objectives and scope for both the overall brand development exercise and the workshop itself.

It's also important to ensure everyone understands the framework you're working within. This should include:

- Key terms of reference (e.g. the difference between an employer brand (reputation/how you're seen) and an Employee Value Proposition (promise/how you'd like to be seen).

- Clarity on the brand hierarchy (e.g. the relationship between the corporate, customer and employer brand, and if relevant, the relationship between the group employer brand and subsidiary company brands).

- The employer brand model (e.g. core positioning and pillars).

- Employer brand activation (e.g. the scope of likely activity once the EVP has been defined, including creative development, validation, internal and external communication, and alignment of people management touch-points).

While much of this material can be delivered in advance as a pre-briefing, a top-line run through is generally useful to make absolutely sure everyone is ‘on the same page’ and has the opportunity to raise any questions or concerns.

(b) The insight platform

The next step is to share the top-line results from the various avenues of research and analysis that have been pursued in advance of the workshop. This would typically include:

- The core target profile (and key talent segments) that need to be considered.

- The business context (including desired capabilities).

- External reputation and attraction drivers (including key perception gaps).

- Employee engagement and retention drivers (including external benchmarks).

- Competitive analysis.

It helps to think of this material as ‘stimulus’ for idea generation, rather than an information download. Don't drown people in data. Highlight the key insights and challenges. Make it as visual as possible. Use ‘personas’ to present your target groups rather than bullet point lists of character traits. Use infographics to present key facts. Use quotations from the research to illustrate key points. Show how your competitors are advertising themselves. Ask participants to share their stories and personal perspectives. Mix up the presentation with exercises and discussions to ensure participants have time to interrogate and digest what's being presented. Make sure people are jotting down their thoughts and ideas. If you get it right, it shouldn't feel like work.

(c) Potential EVP ingredients

The output from the insight session should be the identification of a broad range of potential ingredients for the EVP. To provide some structure to this exercise it is generally useful to provide a framework of categories or territories (as per the positioning wheel introduced in the previous chapter) into which these ingredients can be posted. While some people might view this as limiting people's thinking, the alternative perspective is that too many exercises of this nature spend too much time identifying the same broadly generic ingredients (purpose, teamwork, empowerment, development etc.), and too little time going the extra mile to sharpen and differentiate their positioning within these broad categories. With this framework in place it makes it easier to tease out and identify a more specific range of attributes within each broad category, illustrated as follows:

Territory: Learning and Development

- Potential attributes/claims:

- World-class training facilities

- Management coaching ‘ethos’

- Anytime/anywhere access to learning

- Learning through stretch challenges

- Etc.

(d) The give–get challenge

The most effective EVPs clarify not only what employees can expect from the employer, but also what is expected from employees in return. In other words it's not just simply a one-way promise, but a two-way, ‘give and get’ deal. This helps to ground the EVP in the reality of the business and working experience. If the major priority for the organization is quality, customer focus or enterprise-wide collaboration then it's as important to reflect these desired capabilities in the EVP ‘mix’ as it is to reflect the needs and aspirations of potential candidates. It generally helps to think of this as a mix and match exercise. Some potential pillars may be entirely driven by business needs, some entirely by target talent needs, and others may provide an even balance between both. For example:

- Work–life balance tends to be more give than get from an organizational perspective. It should be seen as an important means of achieving more sustainable levels of performance, but in practice it is often seen as a necessary cost to engage and retain employees.

- High performance tends to be more get than give from an organizational perspective. It doesn't generally appear among employee attraction or engagement drivers but is often a key focus of what is demanded of employees.

- Empowerment tends to be a more evenly balanced deal. The organization ‘gives’ more scope for personal initiative (which most employees would see as a benefit), but in turn they expect to get a high level of accountability from employees to deliver on their performance objectives.

One of the important decisions to make in light of the research results is to decide on striking the right balance in this ‘give and get’ deal. Where the supply of talent exceeds demand, as it has done in many markets during the economic downturn, then you can afford to up-weight the ‘get’ side of the deal. If, on the other hand, the demand for talent outstrips the supply, you will need to up-weight what the organization needs to ‘give’ to attract and retain the people it needs.

(e) The strength–stretch challenge

The most effective EVPs combine credible ‘here and now’ strengths solidly grounded in the current employment experience and more ‘future focused’ stretch aspirations, underpinned by tangible leadership commitments and planned investment. Playing to current strengths builds credibility, which provides the essential underpinning to any brand. Playing to future aspirations builds brand vitality, which is also critical in maintaining a brand's forward momentum and competitive edge.

A useful way of approaching this exercise is to determine where the workshop participants think the list of potential EVP ingredients should be placed along the following strength–stretch spectrum (Figure 11.3). This provides a great opportunity to get the truth on the table, as it can be surprising how many potential attributes end up in the wishful-thinking red zone after this type of exercise.

Figure 11.3 Strength and stretch.

Note that the shared aspiration rating combines two dimensions: consistency and forward momentum. If you are describing the company at its best, then credibility is based on what your organization is capable of, but this can ultimately lead to frustration and disengagement unless it is also accompanied by a strong future commitment to delivering this positive experience more consistently around the whole organization.

As with the give–get mix, the organizational context is important in striking the right strength–stretch balance. If your organization is going through a period of positive and relatively rapid transformation, you can afford to up-weight the aspirational. If your organization is retrenching, then you should up-weight the solidly credible. You need to be very honest with yourselves when it comes to organizational change. The two biggest white lies in change management, from an employee perspective are:

- This is a merger of equals (as opposed to a take-over).

- Down-sizing represents a bright new start (as opposed to a necessary evil).

Whatever you'd like employees to believe, they will see the truth. My favourite example of this was a company suffering the need for significant cut-backs in headcount. They branded this change programme ‘Genesis’, which they hoped would strike the right upbeat note. Their employees took this and re-spun it, referring to the programme among themselves as ‘Exodus’.

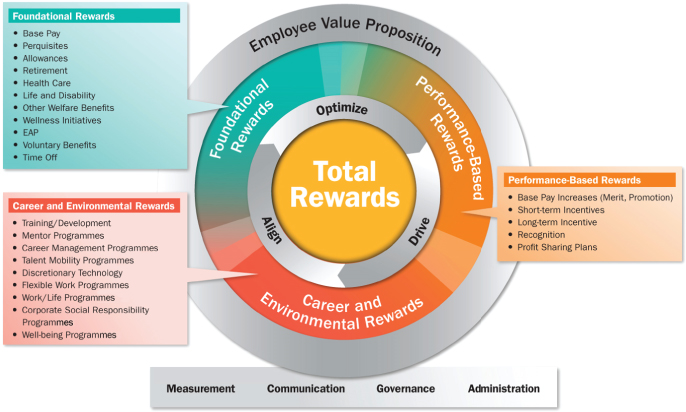

(f) The POP–POD challenge

Once you've narrowed down the territories you want to focus on for your EVP, the next step is to identify your ‘Points of Parity’ (POP) and ‘Points of Difference’ (POD). POPs refer to any attributes you've identified as potentially important and necessary for your EVP that are likely to be the same or similar to your main competitors. A POD is an attribute you believe to provide differentiation and potential competitive advantage. This could be because it's different in kind. This means you're applying a different approach to a certain aspect of people management than your main peer group competitors. An example of this would be P&G's ‘Build from Within’ philosophy, where the company hires the majority of its new recruits as graduates and develops the vast majority of its employees and leaders from within the organization. Alternatively, it could be that you're different by degree. This means you're applying a similar people management strategy to others, but your research indicates that you're delivering much more effectively than your competitors. An example of this would be Santander's professional development, an area in which the Company rates significantly higher than both its immediate financial services competitors and more general high performance company norms.

You should note that this isn't just finding another form of words to describe the same thing. First, you need to ask yourself whether your organization offers and delivers something different in terms of the employee experience and end benefit. If it does, then the next step is to find the right words to capture this point of difference. The following companies all stress the importance of innovation within their organizations, but they deliver innovation in quite different ways. The LEGO Group describes its combination of imaginative play and practical application as ‘Systematic Creativity’. The term used for innovation at Disney is ‘Imagineering’. Channel 4's recipe for creativity (until recently) was simply called ‘Making Trouble’ (Figure 11.4).

Figure 11.4 Pillar differentiation.

A good reference point for this way of thinking is coffee. Why settle for a plain coffee when you can have an Americano, Espresso, Cappuccino, Cortado, Flat White, French Press, Latte, Macchiato, Mocha or Ristretto? Coffee has become the modern equivalent of Eskimo snow because it has become a major part of our day. Like work. With this in mind, you shouldn't serve up the distinctive flavour of work your company offers in the same dull generic way we used to serve up coffee.

The balance challenge in this case is the trade-off between distinctive positioning and immediate comprehensibility. By its very nature a distinctive positioning generally requires more explanation, whereas a generic positioning tends to be more immediately understandable. Since innovation is a common word, it's easy to communicate. ‘Systematic creativity’ and ‘Imagineering’ require more effort to communicate and to understand. The more people you consult with, the more likely your finely tuned and distinctive positioning will be rounded down to a more generic positioning, unless you work hard to explain the rationale. Another classic example of this is the LEGO Group's use of the term ‘Clutch Power’ to describes the organization's distinctive approach to ‘teamwork’. When we started working with the LEGO Group on their EVP, we observed that a distinctive cultural trait of the company was employees' immediate ability to connect, disconnect and reconnect with different working groups. It struck us that this capability was similar in many respects to the ability of LEGO bricks to snap together tightly while also being easy to separate. The unique LEGO Group term for this is ‘clutch power’, and while it would be unfamiliar to outsiders it provided a uniquely meaningful term for the LEGO Group to use internally.

(g) The global–local challenge

The most effective EVPs and messaging platforms balance global consistency with local relevance. Your core pillars should work everywhere, but that doesn't necessarily mean they will be played out in the same way, or that they cover the complete spectrum of things you may need to communicate at the local level. In the EVP development workshop you should discuss whether the core areas you are focusing on are translatable to local markets, and the degree of flexibility you plan to allow in terms of local adaptation. This point is picked up in greater detail in the following chapters on creative development and local validation and adaptation.

(h) The short-list

Addressing the previous four challenges should enable you to refine your initial list of potential EVP ingredients to a short-list of 4–6 core pillars, each containing a cluster of more specific attribute claims and reasons to believe. This is more likely to be an 80% solution than a complete masterpiece. Stopping short of a more complete solution at this stage is an advantage not a failure. To get to the next level you need to test and validate your thinking with a wider audience. Presenting your EVP as ‘work in progress’ at this stage will help people to feel that they are participating in the development of the final EVP rather than just passing comment on someone else's work. This is covered in greater detail in the following chapter.

(i) The core positioning

The purpose of a core positioning is to highlight one overall characteristic that you most want people to associate with your organization as an employer. This single-mindedness is valuable from a brand communication perspective. It's generally easier to establish one major brand association in everyone's minds than lots of little ones. This doesn't mean you can't communicate a range of different messages to different target audiences. It means that alongside these more specific and localized messages there is one overall theme that provides global consistency.

The starting point should be the corporate brand positioning. If the corporate positioning translates well into the employment space it makes a lot of sense to maintain the same positioning in your employer brand marketing. At the heart of Microsoft's corporate brand is the core purpose: ‘To help people and businesses throughout the world realize their full potential.’ This core positioning also works extremely well from the perspective of its employer brand positioning. You should note that this does not necessarily mean that it has to be communicated in the same way. Microsoft uses a number of different campaign headlines to get this core positioning across. On Microsoft's career sites it uses the line: ‘Come as you are, do what you love’, which sums up the message that whatever the experiences, skills and passions you bring to the company, you can take them further with the resources of Microsoft behind you. In their UK graduate campaign, they convey a similar thought through the line ‘What makes you, makes Microsoft’. Coca-Cola Hellenic's ‘Passion for Excellence’, discussed in Chapter 5, provides a further example of using the same positioning for the corporate and employer brand, although in this case it was the employer brand positioning that preceded the corporate positioning. Other good examples include GE's ‘Imagination at Work’, Ericsson's ‘Taking you Forwards’ and Grant Thornton's ‘An Instinct for Growth’.

You may find, however, that your corporate brand positioning works well for customers, but may be rather less attractive from an employment perspective. A good example of this is Citibank's former advertising line: ‘Citi never sleeps’. Great for customers, not so good for employees.

Alternatively, you may find that your corporate positioning provides a good starting point, but you need to refine and sharpen the positioning to make it more relevant and compelling to current and potential employees. Deutsche Bank provides a good example of this. The corporate positioning, ‘Passion to Perform’ clearly sets the tone for the employer brand, but the employer brand positioning ‘Agile Minds’ delivers a more specific message about ‘how’ Deutsche Bank performs, through the mental agility and quick thinking of its people. P&G's longstanding employer brand focus on serving up a rich flow of stimulating challenges (‘A New Challenge Everyday’) has performed a similar role in bringing greater personal relevance to the P&G's overall corporate positioning ‘Touching Lives, Improving Life’.

You may also decide that a core positioning is not necessary. Some companies, like McDonalds, define their EVP in terms of a number of equally weighted pillars, without highlighting one overall characteristic. This provides local countries with more flexibility in choosing how to position themselves in local markets, which fits the devolved and franchised nature of the business.

Given your organizational context, your approach to core positioning may be pretty clear. If it's not then it's recommended that you decide on a number of potential options and test them alongside the EVP pillars among your target audiences, before making a final decision.

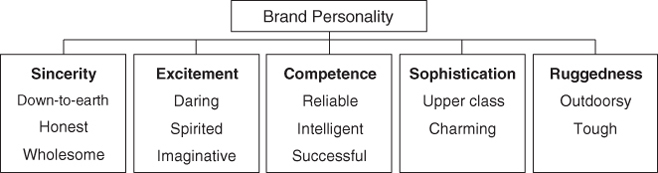

(j) Brand personality

Brand personality relates to the human characteristics or traits you'd like to be attributed to the brand. While the EVP pillars determine what you want to communicate, the brand personality should provide guidance on how you communicate. As for the core positioning, the corporate brand (or customer brand if more appropriate) should provide the starting point for this discussion. If a number of desired personality traits have already been defined, you should try and work within them as it's important that the personality you communicate through your employer brand marketing doesn't conflict with other forms of brand communication. You may, however, decide to up-weight certain of these characteristics, and down-weight others to match an employee audience. Brand personality in the corporate context is sometimes geared to what investors and regulators may be looking for in a brand: competence rather than excitement. If this is the case you may need to mix in a little more emotion to ensure the organization doesn't come across as too ‘corporate’ or ‘stuffy’, particularly among Gen Y talent.

If you have more free reign, then Jennifer Aaker's brand personality map may be useful in providing a starting point for discussion (Figure 11.5).

Figure 11.5 Brand personality dimensions.

Source: Aaker. J (1997) Dimensions of brand personality

WRITING YOUR EVP

It's unwise to try and copy-write EVP statements in the EVP development workshop. While the ‘work-out’ team should be well placed to identify the most promising ingredients, describing the key components of the EVP is an exercise that is better suited to an individual or Lennon and McCartney style duo. As for the selection of the EVP ingredients, there is another balance to strike in describing the elements within your EVP. The primary purpose of the EVP is to define the key components of your employment offer. It should be seen as the foundation for good communication rather than an exercise in creative expression. If there's more sizzle than steak – it sounds good, but lacks substance – then it's not going to provide a very effective brand platform. On the other hand, an EVP description seldom works effectively as a plain list of factual claims. The snow in Antarctica is too dry to make snowballs, which isn't much fun. If your EVP is too dry to get across the spirit of the organization, it's equally unlikely to create much excitement. You therefore need some alchemy to translate what makes sense from a rational point of view, into something that also feels right, something that captures the essence and not just the dimensions of the employment offer.

In order to clarify the ‘deal’ relating to each pillar, you can also seek to define the ‘give’ and ‘get’ components of each pillar. The following is an example taken from the LEGO Group's EVP pillar, ‘Systematic Creativity’ (Table 11.3).

Table 11.3 The LEGO Group – ‘Give and Get’

| Systematic Creativity (Pillar) Our ability to combine disciplined thinking with playful learning and creativity in our everyday work is essential to the ongoing success of the LEGO Group and its people. We strive to ensure our people enjoy plentiful opportunities to exercise their constructive imagination, continually improving the way we go about our business, and realizing their own personal potential through continuous learning and development. |

|

| GIVE • Ability to contribute fresh thinking • An everyday approach to work that will stretch your thinking and imagination. • Frequent learning and development opportunities. |

GET • Fresh/flexible thinking and openness to change • Continuous improvement • Preparedness to take on tough challenges |

Underpinning each component of the EVP should be a number of current ‘reasons to believe’ and, where possible, ‘momentum builders’, that is actions planned in the near to medium term that will further reinforce the brand claims. For example, when GSK developed their global EVP in 2011, one of their pillars, ‘Sense of Purpose’, was supported as follows in Table 11.4.

Table 11.4 GSK's reasons to believe and momentum builders

| GSK – Sense of Purpose – (Pillar) We all contribute to make lives better across the world |

| Reasons to believe: • GSK's PULSE Volunteer Partnership Programme provides an opportunity for high-performing employees to volunteer their professional expertise towards sustainable change in the areas of healthcare, education and the environment. • Orange Day has enabled thousands of employees to take one day fully paid to volunteer for a chosen community project, organization or cause which they support. • GSK employees who have pledged their time, effort and regular commitment to a cause, are invited to apply for financial grants through our Making A Difference (MAD) programme in the UK and the GSK Investment in Volunteer Excellence (GIVE) in the US. • GSK and Save the Children have developed a long-term strategic partnership combining expertise, resources and influence to help save one million children's lives. This provides GSK employees with an opportunity to unite through volunteering and fundraising with the aim of raising £1 million a year, which GSK will match. Momentum builders: • Incorporating exposure to patients/consumers into new manager induction programme. • Globalizing R&D Focus on the Patient Programme, which aims to inspire deeper commitment and understanding in GSK employees about the urgency of our work to deliver better medicines to patients. • Increasing employee awareness of the NGOs and charities supported by GSK. |

SUMMARY AND KEY CONCLUSIONS

- EVP development is like alchemy. You need hard data and evidence, but you also need some magic to transform these base materials into something that lifts the spirit and fires the imagination.

- Some companies use an EVP to underpin a communication campaign, but the EVP is increasingly regarded as a more strategic platform for a much wider range of employer brand communication and experience.

- If the desire is to create a more integrated brand platform, then it is essential to include a mix of HR, marketing, communications and line managers in the development team.

- The key components of a typical EVP, defining the core areas of employer brand consistency, are the brand positioning, personality and pillars.

- It is increasingly common to describe the pillars of the EVP in terms of both the ‘give’ and ‘get’ of the employment deal, not simply a unidirectional set of employee promises.

- The most effective EVPs include a healthy balance of current strengths and future aspirational stretch. For stretch claims to be credible, they need to be underpinned by clear and tangible leadership commitment and investment.

- It's often relatively straightforward to identify general themes and territories for your EVP pillars (teamwork, innovation, career progression etc.). The more challenging task is to determine the distinctive way in which your organization can position itself within each of these territories.

- The art in writing an effective EVP is to balance clear definition of the brand elements while also conveying the right feeling, spirit and culture of the organization.

- To support each of your claims, it is important to identify current ‘reasons to believe’ and future ‘momentum builders’ (the steps being taken to reinforce the brand claim moving forwards).

- Most leading employers redevelop or refresh their EVPs every 4–5 years.