Chapter 18

Managing the Brand Experience

‘Communicate your beliefs at all times, and if necessary use words.’

Attributed to St. Francis of Assisi

When Pope Francis took office in 2013 he traded in his courtesy Mercedes for a Ford Focus. He was not the first Pope to underline the Catholic Church's commitment to the poor, but he has done more than most to demonstrate his beliefs through his actions. Alongside his rejection of executive class cars, he also passed over the regal papal apartments in favour of a boarding house which he shares with 50 other priests. He rejected the fur-trimmed velvet capes that popes have worn since the Renaissance and decided that plain back shoes were more to his liking than Benedict's red papal slippers. He broke with the papal Holy Week tradition of celebrating the evening Mass at a Rome basilica, choosing instead to perform the service at a small chapel in a juvenile detention centre, where he washed and kissed the feet of 12 young offenders.1 He hasn't just preached humility, he has practised it, and in leading by example he has revitalized the purpose and reputation of the world's oldest multinational. There was a reason that Jorge Mario Bergoglio took the name Francis. He believed in St. Francis of Assisi's concern for the poor, and he shared his belief in actions before words. The ‘Francis Effect’ is reshaping expectations of what it is to be a Catholic priest, and in turn it is beginning to reshape people's experience of the Catholic Church.

THE CUSTOMER BRAND EXPERIENCE

Delivering a reliably positive experience has always been a central concern of brand management. In the mid-1880s, before the term was invented, one of the first great brand pioneers, William Lever, founded his fortune on his consistently reliable and ‘sweet-smelling’ Sunlight Soap, in a market regularly tainted by inferior and unreliable product. His advertising was imaginative, but it was the brand experience and ‘word of mouth’ that ultimately secured his success. In the early 1900s, retail pioneers like Gordon Selfridge were similarly clear about delivering a consistently distinctive customer experience. The man who first coined the phrase: ‘the customer is always right’2 described his original vision for his new department store, Selfridges, as ‘delighting them with an unrivalled shopping experience’ (which included such innovations as in-store coffee shops) and training his staff in the ‘Selfridges Way’ to ensure a distinctively consistent level of customer service.3

While attempts to manage the total customer experience were present among both product and service brand pioneers, the systematic approach to brand management first introduced by P&G in the 1930s has mostly been dominated by fast moving consumer goods. While the value of reputation, differentiation and consistency have always been appreciated by the service sector, it is only within the last 20 years that brand management has been as systematically and rigorously applied to service brands.4 One reason for the service sector's relatively late adoption of a fully rounded approach to brand management is the level of complexity involved.5 While there are clearly exceptions to the rule (the NASA Space Shuttle, the Ikea ‘flat-pack’), product brand experiences tend to be a lot simpler than service experiences, and therefore that much easier to manage.

From the perspective of the service provider this complexity has two principal dimensions: operational complexity and interpersonal complexity. The first dimension relates to the number of component parts brought together under the same brand name, in terms of the number of different services offered, the number of steps in a typical service transaction or the number and/or complexity of products offered in relation the service. The second dimension relates to the potential complexity of the personal interactions between customer and provider, either in terms of the number of different people involved in the service transaction or the depth of knowledge or quality of relationship required to deliver the service effectively.

To illustrate the potential complexity from a customer perspective, your customer experience of a mobile phone operator is likely to involve an interaction with the retail store personnel advising you on which handset and tariff would best suit your needs; your ability to pick up a regular signal; your experience of the additional service features offered by the provider in addition to regular telephony; and your interaction with customer service centre employees when you have a query or problem to solve. Despite the (hopefully) straightforward personal interactions involved, the total service experience involves many different component parts and therefore presents significant challenges to delivering a consistent, on-brand experience.

Where service companies are generally more confident (and more focused) is in managing the operational complexities. Repetitive operational tasks are the most conducive to training by rote, automation, measurement and quality control. The interpersonal complexities involved in delivering a consistent customer experience have always been more difficult to manage, and in many service businesses receive far less attention. As Colin Shaw pointed out in his study of service organizations: ‘In our experience organisations are obsessed with the physical aspects of the customer experience. They have meeting after meeting about the delivery timescales, lead times, range of products, the time it takes to answer a phone call’, but spend relatively little time trying to understand the emotional dimensions of the service experience, which are far more dependent on interpersonal interaction.6

You would think from service providers' focus on operational consistency that this was the most important dimension in driving customer satisfaction. Operational consistency is clearly vital in avoiding customer dissatisfaction. If something doesn't work, it doesn't matter how engaging the interpersonal experience is, you're not going to deliver satisfaction. But if the ambition is higher, and the organization is striving to achieve customer delight, loyalty and advocacy, most research suggests that the balance of attention needs to shift to the interpersonal dimension of customer service.

THE EMPLOYEE'S ROLE IN DELIVERING THE BRAND EXPERIENCE

There is significant evidence to suggest that interpersonal factors are often more important than operational factors, and that engaged and satisfied employees are more likely to deliver a consistently positive service experience.7–9 The evidence would also suggest that employees are increasingly key in developing sustainable service brand differentiation, not only through the development of a consistently positive service attitude, but through the emotional values that tend to be evoked by a particularly distinctive style of service. It is generally agreed that these intangible brand characteristics are far more difficult for competitors to copy than the operational components of a service brand experience.10 If you study the most successful service brands the most obvious point of similarity is the stress they place on the role their people play in delivering a distinctive brand experience. In his study of the ‘Starbucks Experience’, Joseph Michelli commented:

‘While seemingly endless details go into producing the emotional bond that loyal Starbucks customers feel, often the most important aspect of this bond is the personal investment of Starbucks partners [employees]’.11

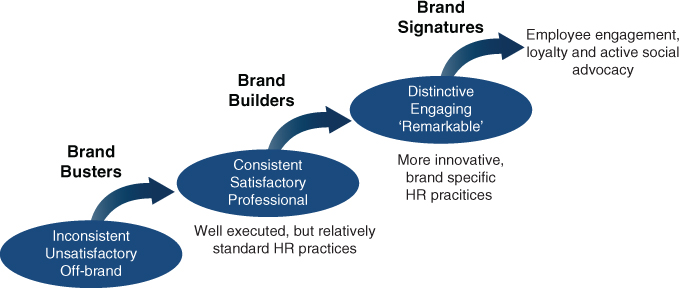

Sean Smith, the author of Managing the Customer Experience, identifies three levels of customer experience, with the ultimate goal of delivering a differentiated brand experience that is not simply reliably good in delivering against service expectations, but distinctively great in delivering unique customer value (Figure 18.1).12

Figure 18.1 Customer brand experience levels.

Source: Adapted from Shaun Smith, Smith & Co.

While these examples are derived from consumer-oriented service brands, the central role of people in delivering a positive customer experience is equally true of those businesses where interpersonal complexity comes as standard. In professional services (accountancy, law, fund management, medicine, IT services and management consultancy) the value of the business largely depends on the knowledge and expertise of its people, and the ability of its people to inter-relate successfully with customers (and each other).13 Until relatively recently, most professional service firms competed on the basis of the quality of specialist knowledge and technical expertise provided by their employees. The top law firms paid more to secure the employment of top lawyers, which in turn enabled them to compete for the most high quality work and charge the richest fees. It's a deceptively simple operating model. However, from the customer perspective it has been prone to suffering the same flaws as the operationally fixated model that dominates much of the consumer service sector, in that it focuses on the more functional, rational and controllable dimensions of the service at the expense of the more intangible and emotional interpersonal dimensions. Does this matter in professional services? It has long been the conventional wisdom that business-to-business interactions tend to be more functional and rational than consumer service encounters, but recent studies suggest that the most important attributes in driving preference are not technical expertise but the interpersonal qualities of trust and commitment.14 In Marketing the Professional Services Firm, Laurie Young recently concluded that the day-to-day client-facing activities of employees ‘are probably the most influential aspects of building a professional services brand’.15

In many consumer-oriented services, where the typical service interaction is relatively simple and easy to predict, it's often managed as though it were a straightforward extension of the operating manual. This is most evident in the behaviour of telephone service centres where there is an obvious script. How often have you heard the phrase: ‘Is there anything else I can help you with?’ when the ‘operator’ hasn't even dealt with the original reason for your call? This is altogether the wrong kind of consistency when it comes to the service experience, since authenticity is very important to brands and attempts to over-control the service encounter with ‘fake’/scripted behaviour often backfires both functionally (through lack of responsiveness) and emotionally (through lack of genuine personality).

In many cases, companies try and impose ‘tight’ controls over what their employees say and do during the service encounter16 but have a relatively ‘loose’ understanding of the brand promise. In contrast, many of the most celebrated service companies take the opposite approach. They ensure people have a clear understanding of the brand promise, and then encourage employees to act naturally.

Pret a Manger CEO, Andrew Rolfe, claims the only guidelines they give people on customer service are: ‘to greet the customers when they arrive; look them in the eye when you put the money in their hand; make sure you say something when they leave; but more than anything else, be yourself’.12

In this type of customer service organization, there is less emphasis on controlling the specifics of the service interaction and more emphasis on the cultural context within which interpersonal interactions take place. If culture can be described as a ‘collective programming of the mind’ that reinforces ‘patterned ways of thinking, feeling and reacting’17 then marketing has continued to evolve techniques for programming the way people within the organization think, feel and react towards customers and the brand.

INTERNAL MARKETING

The task of ensuring employees understand the brand promise and their part in delivering an on-brand customer experience has generally been described as internal marketing. Internal marketing (IM) lacks a widely accepted definition, however the most consistent theme has been motivating customer focus. A recent IM literature review presented three definitions (between 1989 and 2000) variously describing the primary objective of IM18 as:

- instilling ‘service-mindedness and customer-oriented behaviours’;19;

- focusing ‘staff attention on the internal activities that need to be changed in order to enhance marketplace performance’20 and

- ‘creating motivated and customer-oriented employees’.21

This orientation continues to be echoed in Kotler's most recent Principles of Marketing with the objective of internal marketing defined as: ‘to train and effectively motivate customer-contact employees … to provide customer satisfaction’.4

This ‘outside-in’ approach to internal marketing focuses on communicating the customer brand promise and the attitudes and behaviours expected from employees to deliver on that promise. While it is clearly important for employees to understand their role in delivering the customer brand promise,22 the result can often be short-lived if employees feel they are no more than a ‘channel to market’. If the brand values on which the service experience is founded are not experienced by the employees in their interactions with the organization, the desired behaviours will ultimately feel superficial, ‘a show put on for customers’ rather than the natural extension of a deeply rooted brand ethos.

INTERNAL BRANDING

Over the last 10 years there has been a shift in emphasis from internal marketing to internal branding, which takes more of an ‘inside-out’, value-based approach. Internal branding seeks to develop and reinforce a common value-based ethos, typically attached to some form of corporate mission or vision. The roots of this approach can partly be traced to the resource based view of strategy,23 though the more evident driver in terms of widespread readership was the highly influential ‘Built to Last’ study which sought to demonstrate that companies with consistent, distinctive and deeply held values tended to outperform those companies with a less clear and articulated ethos.24. In contrast to Porter's outside-in approach to differentiation,25 the resource based view of strategy suggests the distinctive cultural characteristics and capabilities of the organization are the only sustainable route to competitive advantage in that everything else is open to inspection and copying.26

In practice, the execution of internal branding has run along very similar lines to the communication-led engagement programmes typical of internal marketing, the main difference being a less narrowly defined focus on the customer brand experience in favour of a broader range of brand-led corporate goals and objectives.

While ‘living the brand’ is often the stated desire of these internal branding programmes, their focus on communication-led, marketing methods (however involving or experiential) has been prone to the same failings of conventional internal marketing. As many commentators have pointed out, it is very difficult to change an organization's culture. As Amazon's founder, Jeff Bezos, asserts: ‘One of things you find in companies is that once a culture is formed it takes nuclear weaponry to change it’.27 You cannot assert your way to a new culture, no more can you assert your way to a strong brand, it needs to be consistently and continuously shaped and managed.

One of the most powerful factors in shaping an organization's culture is the consistent alignment of leadership behaviours with their stated brand beliefs, and recent studies have highlighted the need to move beyond the tendency of many organizations to focus on the star qualities of their CEO towards a more pervasive brand of leadership.28 While this represents an interesting step forwards in conceptualizing the relationship between leadership style and the brand, it does not take into account the wide range of other factors that need to be addressed in shaping the employee experience, which often lie in the domain of Human Resources.

In the internal marketing and branding literature it has long been recognized that HR plays a potentially important role in embedding the desired brand ethos and culture, however their role has often been restricted to communication support, rather than playing a more strategic role in shaping people management practices to reflect the desired brand experience. As Martin and Beaumont state in their review of the relationship between branding and people management:

‘[Marketing] literature is rooted in the belief that communications are the main source and solution for all organisational problems. It tends to restrict the role of HR to communicating brand values, rather than being the source of such values and the driver of key aspects of strategy.’29

In turn this may have contributed to a general HR reluctance to participate more fully in brand-led initiatives, because it has perceived them to be more concerned with spin than substance.

As stated, the inherent weakness of internal marketing, internal branding and, more recently, employer branding has been the over-emphasis placed on communicating brand promises at the expense of longer term management of the employee experience. This is now being addressed through an adoption of the same thinking that has driven recent developments in management of the customer brand experience, namely if you want to deliver a consistent on-brand service experience, it's not just a question of managing your communication channels, you need to manage every significant operational and interpersonal ‘touch-point’ with the customer.

MANAGING THE EMPLOYEE'S BRAND EXPERIENCE

While the employee experience is far more complex than any service experience, there is a recognition that organizations would benefit from adopting a similar approach. People management involves a wide range of ritualized processes and HR ‘products’ which can be described as employee touch-points. The term ‘customer corridor’, used to describe a relatively predictable sequence of experiential ‘touch-points’, can equally be applied to recruitment, orientation and people management processes. Likewise, core values and competencies can be seen as a framework for governing the everyday experience of employees through the communication and behaviour of their immediate line managers and corporate leaders (Figure 18.2).

Figure 18.2 Employer brand experience touch-points.

As for the customer experience, being consistent is good, but being both consistent and distinctive is even better. If you want to deliver a distinctive customer brand experience, and that experience depends heavily on interpersonal interactions, then you need to ensure your employer brand attracts the right kind of people30 and your employer brand management reinforces the right kind of culture (from the customer-facing front-line to the deepest recesses of every support function).

To ensure your culture is aligned with the desired customer brand experience, it clearly helps to have a distinctive ‘brand of leadership’, but it is equally important to ensure that your people processes are also distinctively in-tune with your brand ethos. These ‘signature’ employer brand experiences31 will help to engender a distinctive brand attitude, generate distinctive brand behaviours and ultimately reinforce the kind of distinctive customer service style that will add value to the customer experience and differentiate an organization from its competitors (Figure 18.3).

Figure 18.3 Employer brand experience levels.

‘Touch-Point Planning’ involves reviewing the current alignment of people management practices with the EVP, setting priorities to turn employer brand busters into brand builders and identifying opportunities to reinforce or develop new brand signatures. Brand busting experiences result from either poor process design or poor execution. In small to medium sized companies, a strong leadership presence and tightly-knit culture can sometimes deliver a consistently positive employment experience with very few formal people management processes. In larger companies, an absence of well-designed and executed process almost inevitably leads to significant inconsistencies.

One of the greatest disadvantages in large-scale organizations is complexity. One of the greatest potential advantages of scale is the ability to buy or build superior systems and processes and apply them consistently to everyone's benefit. The key qualifiers are empathetic design, training and communication. Empathetic design moulds systems and processes to people's behaviours, rather than imposing more arbitrary rules and pathways that may look good on the drawing board, but feel strange to the end user.32 Apple's products are so intuitively easy to use because they follow similar principles. There is also a tendency for systems and processes to be over-engineered by ‘specialists’, increasing complexity and control at the expense of simplicity and empowerment. From an employee perspective, processes often feel like they have been designed to limit what people can do and check what they've done rather than enabling them to do more. Even where processes have been designed with the end user firmly in mind, the right kind of communication and training is also critical to the user experience. Customers are unlikely to adopt a new service unless they are clear about the intended benefits and clear about how the service works. It's no different for employees. Communicating the features of a new process will not get you very far unless you're also clear about why there is value in adopting the process and spend time demonstrating how to use it effectively. A well-designed people management process will often become a brand buster simply because insufficient time and investment has been applied to the how and the why.

BRAND SIGNATURES

If your organization has successfully addressed these challenges, and has a consistently positive and professional approach to the people management process, the next level to aspire to from an employer brand perspective is the development of ‘signature’ experiences.

‘A signature experience is a visible, distinctive element of an organization's overall employee experience. In and of itself, it creates value for the firm, but it also serves as a powerful and constant symbol of the organization's culture and values.’31

These signatures can define processes that are so central to the organization that they could be seen by many as defining its core ethos, like ‘Kaizen’, Toyota's continuous improvement process, or GE's lean-thinking ‘Work-Out’. In other cases it simply represents a distinctive aspect of the business, like IBM's online collaboration ‘Jam’ sessions. Some companies seem to be naturally drawn to creating ‘signatures’. While Google's success as an employer can be partly explained by its phenomenal success as a business, its distinctive approach to people management has undoubtedly made a significant contribution to its long reign at the top of every world lists of best places to work. Who hasn't heard of ‘20% time’? This is the term used to describe Google's encouragement of software engineers to spend one day a week on a personal passion project, unconnected with their ‘regular’ work. There is of course, the ‘pets at work’ policy, the 24-7 gourmet food, and the famously fun working environments (slides, ski-lift meeting rooms etc.). This may sound like the recipe for every tech start-up, but there are important cultural differences between the leading Silicon Valley players that are reflected in their choice of brand signatures.

Apple is far less laid-back than Google. There is no 20% time. There are no evident work–life balance policies. It's clear that Apple demands extreme dedication and hard work. As their career site states:

‘A job at Apple is one that requires a lot of you, but it's also one that rewards bright, original thinking and hard work. None of us here at Apple would have it any other way.’

Apple's people management policies are designed to reinforce self-reliance. It underplays the notion of career paths to encourage people to actively seek out their own information and contacts about opportunities around the company. Apple also spends a great deal less on benefits than its immediate competitors. After researching the company's approach to talent management Dr John Sullivan concluded ‘Apple's offerings are Spartan when compared to Google, Facebook and Microsoft’.33 Another signature difference is Apple's 10:3:1 approach to innovation. This involves up to ten teams working in isolation from each other on the same product area. Then following a formal peer review, the resulting product ‘mock-ups’ are pared down to three, and then down to one. Unlike most other companies, Apple makes a virtue of silos and secrecy to eliminate any threat of group-think. You can't argue with their success.34

Facebook's approach is almost the exact opposite to Apple. ‘Being open’ is a core feature of Facebook's EVP and belief system, and this means doing everything possible to encourage openness and collaboration between its employees. This includes standing desks that help to create a much more open working environment (in addition to healthy posture). It means providing new joiners with complete access to Facebook's computer code. It also informs two of their signature innovation processes. ‘Hackathons’ involve eight-hour, all-night, sessions with large groups of employees brainstorming new product concepts. Facebook also runs ‘Project Mayhem’ events, which are longer 27-hour sessions, focusing on mobile product ideas, which generally require more planning time.35

TOUCH-POINT PLANNING

While many of these processes have been driven from a business perspective, with a very definite commercial outcome in mind, the same kind of thinking can be applied to most people management processes, with the dual objective of increasing performance and reinforcing a distinctive cultural identity and EVP. We have conducted this kind of ‘touch-point’ planning session with a wide range of leading companies, including E.ON, Lafarge, The LEGO Group, JTI, Novartis, Santander and Unilever. Touch-point planning involves four key stages: review, prioritize, design and deliver.

(a) Conducting a touch-point review

Once you have defined your EVP, the first step is to conduct a review of current people management processes and practices to identify current brand busters, builders and signatures. This should not be restricted to processes that fall within the governance of HR, but include everything that may have a significant effect on the internal employer brand experience, including employee communication, facilities management and the working environment. This will be more manageable if you start with a relatively broad framework. Santander used the following categories in their recent touch-point planning review (Table 18.1).

Table 18.1 Employer Brand Management touch-points (Santander)

| Recruitment & Orientation | Employee Communication | Performance Management | Learning & Development | Reward & Recognition | Facilities & Environment |

| Recruitment Marketing | Top-Down Communication | Performance Reviews | Professional Development | Compensation | Workplace Design |

| Candidate Management | Bottom-up Communication | Feedback & Coaching | Personal Development | Flexible Benefits | Social/Recreational Facilities |

| Onboarding & Orientation | Lateral/Social Communication | Flexibility & Work-Life Balance | Leadership Development | Recognition Schemes | Workplace Technology |

The ideal approach would be to conduct some customized research into employees' perceptions of these different aspects of the employment experience. This might take the form of focus groups with key employee segments or a more extensive quantitative survey. New joiner surveys and employee engagement research may provide some useful insights, but these methodologies often fail to provide the kind of granular information required to diagnose satisfaction with specific people management processes, and very seldom provide the kind of information required to diagnose alignment with an EVP. Even where this level of detailed research is unavailable, we have found that the HR leadership team, HR ‘Centres of Excellence’ and other relevant functional heads generally have a good enough understanding to conduct a top-line review of people management performance and alignment. For each of the areas under review, it's important to rate the brand consistency and alignment of both the process design (how things are supposed to work) and practices (how they actually work). We have found that colour coding each touch-point category according to its buster/builder/signature status provides a useful visual summary of the overall results of this exercise. Many companies use a traffic light system, with green designating on-brand, orange designating room for improvement and red designating an urgent need to redress.

(b) Touch-point prioritization

Once this ‘big picture’ review has been conducted, it makes it far easier to see what needs to be done to bring the employment experience into alignment with the Employee Value Proposition. The most obvious place to start is an assessment of current HR priorities in light of your touch-point analysis. If the EVP has been developed with this forward plan in mind then there should be a reasonable match between areas of recognizable stretch and HR improvements that are already underway or in the HR pipeline. The next step is to identify the gaps.

- What must you do to address remaining and significant brand busters? If there are key areas of the employment experience in conflict with your brand promises it doesn't matter how well you are delivering in other areas, the brand will always be compromised.

- What should you do to exploit the most immediate opportunities to strengthen the brand through more effective people management or create more signature brand experiences?

- What could you do given the right resources and budget to deliver further improvements over time?

(c) Touch-point design

Having established your priorities, the next step is to address the changes that may need to be made to re-design people processes and practices. This may involve re-designing the process itself, or if the shortfall in employee experience relates to the consistency or style of implementation you may need to re-design and/or re-invest in training and communication.

While your facilities management can fall within this process framework, shaping the overall design of the working environment is generally a much bigger question. For organizations considering the right kind of architectural design for a new build, or re-configuring the workplace design of an existing building, the EVP should be a conscious point of reference. In most leading companies there is now a very conscious desire to reflect the brand values within the design of the workplace, and you can find many excellent examples of this in the book I Wish I Worked There! by Kursty Groves.36

Signature experiences demonstrate the points of difference (PODs) that you should have already identified during the EVP development process. The experience may be ‘different by degree’ in terms of the amount of emphasis or investment dedicated to the underlying process or practice. For example, you may have a career path model that is similar to other companies, but you may have made a greater investment than your leading talent competitors in the kind of software that enables employees to map out different career options and training requirements. Alternatively, it could be ‘different in kind’, which means it includes elements that are relatively unique to your organization. These need not require large investments. One of my favourite examples of this ‘difference in kind’ was a practice designed by one of the Virgin companies to re-hire talent that had recently left to join other employers.

SUMMARY AND KEY CONCLUSIONS

- Delivering a consistent and distinctive brand experience has always been a central concern of brand management.

- The ultimate goal is to deliver a differentiated brand experience that is not simply reliably good at delivering against service expectations, but distinctively great at delivering unique customer value.

- If you want to deliver a consistent on-brand service experience, it's not just a question of managing your communication channels, you need to manage every significant operational and interpersonal ‘touch-point’ with the customer.

- There is significant evidence to suggest that interpersonal factors are often more important than operational factors and that engaged and satisfied employees are more likely to deliver a consistently positive service experience.

- Internal marketing focuses on communicating the customer brand promise to employees, and the attitudes and behaviours expected of them to deliver on that promise.

- If the brand values on which the service experience is founded are not experienced by the employees in their interactions with the organization, the desired behaviours will ultimately feel superficial rather than the natural extension of a deeply rooted brand ethos.

- This has led a number of leading organizations to adopt the same kind of touch-point approach to managing the employee experience as companies apply to managing the customer brand experience.

- As for the customer experience, being consistent in delivering your employer brand experience is good, but consistent and distinctive is better.

- Touch-point planning involves reviewing the current alignment of people management practices with the EVP, setting priorities to turn unsatisfactory ‘brand busters’ into positive ‘brand builders’ and consistent brand builders into distinctive ‘brand signatures’.

- Signature brand experiences may be ‘different by degree’, in terms of the amount of emphasis or investment dedicated to the underlying process or practice, or ‘different in kind’, which means it includes elements that are relatively unique to your organization.