Chapter 20

Employer Brand Metrics

‘Not everything that can be counted counts, and not everything that counts can be counted.’

Albert Einstein

Forget that Great Barrier Reef job, the sexiest jobs in the twenty-first century will be in data science. This was the prediction made by Thomas Davenport and D.J. Patil in the Harvard Business Review.1 They should know. They're data scientists. They crunched the numbers and they came out sexy. There's been a lot of Big Data talk over the last couple of years. It's been heralded as a management revolution.2 The technology research house, Gartner, expects the market for Big Data and analytics to generate $3.7 trillion in products and services, and 4.4 million new jobs by 2015.3 That's a lot of sexy jobs, and filling those jobs is clearly going to need some brain power to be applied to talent analytics.

If Big Data is sparking a revolution in general management, then Predictive Analytics may well be the ‘next big thing’ in talent management.4 According to Thomas Davenport, it all started with baseball.5 If you've seen the film Moneyball then you'll know that the conventional approach to judging the future performance of a baseball player was based on assessing ‘the five talents’: how well you can catch, how fast you can throw, how fast you can run, how hard you can hit and how far you can spit. I'm not sure the last one is quite right, though it seems to be a widely shared skill among baseball players. The point is these qualities feel intuitively right, but they're factually wrong. At least, none of these factors turned out to be the most important predictor of future performance. When Billy Beane took on the failing Oaklands Athletics baseball team, he also took on an Ivy League data analyst, Peter Brand, to help him hire potential players that other teams had overlooked.6 He ignored the five talents and focused on the data, which led him to the conclusion that the number one predictor of future baseball performance was a player's On-Base Percentage (how often a batter reaches base excluding fielding team errors). During the 2002 season, with their new OBP selected hires in place, Oaklands Athletics went on to win a record-breaking 20 straight games in a row, competing on a par with teams paying out three times more in salary.

Google reached similar conclusions. It used to be the case that hiring at Google was a similarly intuitive process reliant on famously quirky brain teasers and many, many different points of view. It was not unusual in the past for a potential recruit to undergo interviews with over a dozen different people before a hiring decision was made. And of course, for a long period of time it was also known that nobody was hired without the nod from the Google founders, Sergei and Larry. This felt intuitively right, but then Google hired their own version of Peter Brand. Laszlo Bock joined Google in 2006 to set up a new function called ‘People Operations’. His mission was to ‘apply the same discipline and rigour to people operations that we use to manage Google's business operations’.7 The desire was to ensure that all people decisions were informed by data and analytics. When they looked at the hiring process, there were some unsettling surprises. As Laszlo commented in a recent New York Times interview: ‘We looked at tens of thousands of interviews, and everyone who had done the interviews and what they scored the candidate, and how that person ultimately performed in their job. We found zero relationship. It was a complete random mess.’ 8 The Google team also recognized that brainteasers didn't predict anything. The only purpose they appeared to serve was to make interviewers feel smart. Google's job candidate interview methods are now far more data-driven, with a heavy emphasis on structured behavioural interviews (where you ask people to speak of their own experience, rather than respond to more hypothetical questions). The company also conducts far fewer interviews per candidate, after discovering that four interviews were enough to gauge whether an interviewee is going to be a good fit for a position.9 These changes have been made out of necessity, not simply analytical virtue. Google now employs over 50,000 people around the world, and receives somewhere between 2 and 3 million applications a year, from which it makes thousands of new hires. Nevertheless, Google's data driven approach has begun to shake up the way HR thinks about talent metrics.

The use of measurement to determine the effectiveness of different employer brand marketing activities has been relatively piecemeal in most organizations. Only 25% of the participants in our employer brand practice benchmark survey claimed to be measuring the external impact of their employer brand activities. This reflects the generally poor state of talent analytics within most organizations. In Deloitte's Global Human Capital Trends survey (2014)10 Talent and HR Analytics were reported to be one of the most important trends in people management. It was also the trend which people felt organizations were least ready for. Among HR managers only 12% felt ‘ready’, 47% felt ‘somewhat ready’ and 41% felt ‘unready’. From a senior line management perspective this looks like wishful thinking. Among this group only 7% felt their organizations were ‘ready’ to use talent analytics, 35% felt ‘somewhat ready’ and 57% felt ‘unready’.

HR has always collected a lot of data, but has tended to be poor at analysing and applying it. One of the key reasons for this is the complexity of HR data. Bersin Deloitte's research on HR systems found that the average large company has more than ten different HR applications which generally makes data linkage a highly time consuming and expensive task. The second likely reason is expertise. Data analytics demands a very different skill set from conventional HR, and finding the right talent to perform the job is difficult. A recent survey involving 300 IT professionals revealed that 55% of data analytics projects are abandoned, and one of the most common reasons for failure was managers lacking the right expertise to ‘connect the dots’ and form appropriate insights.11

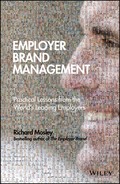

Among those attempting to measure the impact of their employer brand marketing in our benchmark practice survey, the most common metric (used by 83%) was benchmark rankings (Universum, ‘Great Places to Work’ etc.). Two-thirds used employee turnover as a key performance indicator, and around half used cost of recruitment, or quality of hire. The majority of participants recognized the need to improve their metrics and plan to do more. This reflects another global research study conducted by LinkedIn.12 They found that the use of data analytics in recruiting was increasing, but currently only a quarter of participating organizations claimed to be satisfied with their use of data to understand talent acquisition effectiveness and opportunities, with significant variation between different regions (Figure 20.1).

Figure 20.1 Effective use of talent acquisition data.

Source: LinkedIn Survey 2013

How well does your organization use data to understand talent acquisition effectiveness and opportunities? (% Positive responses)

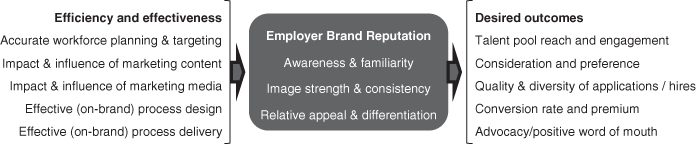

While the focus, as above, has largely been on talent acquisition metrics, diagnosing and tracking your employer brand health and marketing effectiveness requires a wider focus, including measures of internal brand perception and engagement. Ideally you should be capturing data at every stage in the talent lifecycle from identification of your potential talent pool through to fully productive employment (Figure 20.2).

Figure 20.2 Key stages in the talent lifecycle.

Through these key stages there are three major categories of measurement that you need to consider to fully evaluate the strength of your employer brand and the effectiveness of your talent and employer brand marketing activities.

- Brand Reputation and Experience. How are you perceived and experienced by your target audiences and current employees?

- Desired Behaviours and Outcomes. To what degree do current brand perceptions and experiences appear to be driving desired behaviours?

- Marketing Efficiency and Effectiveness. What is the relative cost and value of different communication content and media, and different talent practices in delivering desired results?

Most recruitment measurement approaches currently seek to understand the linkage between marketing media (source) and desired outcomes (applications and quality hires), but seldom integrate this with data relating to brand reputation and experience. Internally, most employee surveys measure the linkage between the overall employment experience and engagement, but seldom measure the impact of more specific brand associations. The following provides a more comprehensive framework of the metrics and linkages required for a more complete (and actionable) understanding of your employer brand (Table 20.1).

Table 20.1 Key Employer Brand Measures

| Process Efficiency and Effectiveness | Brand Reputation and Experience | Desired Behaviours and Outcomes | |

| External | Accurate workforce planning and targeting Impact of marketing content and media relative to cost Effective recruitment process design and delivery Applicant/candidate satisfaction with recruitment practices |

Brand awareness and familiarity Brand image strength and consistency Relative appeal and differentiation (Employer Brand Reputation) |

Talent pool reach and engagement Consideration and preference Quality and diversity of applications and hires Cost per hire/Time to hire Conversion rate and premium Positive word of mouth (likes/shares etc.) |

| Internal | New joiner satisfaction with on-boarding practices Impact of internal communication content and media relative to cost Effective HR process design and delivery Employee satisfaction with people management and communication practices |

Internal fulfilment of your employer brand promises (EVP Index) |

Talent bench strength Engagement and retention Performance Advocacy and referral |

EMPLOYER BRAND REPUTATION

External reputation represents a fundamental component of your employer brand equity (the inherent value of your brand). A clear and distinctive reputation represents the desired cumulative result of your past marketing efforts. Once established, it also casts a golden glow of trust and favourability across your future marketing activities. While some organizations enjoy high levels of global awareness and a fairly consistent reputation, it pays most to be far more targeted in their measurement of brand reputation. In other words, assessing what people know and think about your organization should always be carefully qualified by who you are choosing to ask.

Brand reputation can be a complicated and slippery concept to pin down. Employer brand reputation tends to vary significantly across different target audiences depending on people's level of familiarity with your brand and their personal perspective and preferences. It also has highly permeable boundaries overlapping considerably with your overall corporate reputation, perceptions of your product and service brands, industry reputation and perceptions of the company's country of origin. Nevertheless, by breaking the concept reputation down into its component parts, it is possible to deliver some very useful measures and analytics.

(a) Brand awareness and familiarity

What percentage of your target audience has heard of your organization and knows what your organization does?

It's important to distinguish between familiarity with your products or services, and a familiarity with the kind of employment opportunities you might offer. In many cases potential candidates may exclude themselves from considering your organization as a potential employer because they only associate you with the jobs they can see or imagine. People typically underestimate the range of positions available in support functions. For example, from L'Oréal to P&G, STEM graduates often fail to consider the range of scientific and engineering roles required to deliver familiar products and services. This is one of the reasons that a favourable impression of your brand may not equate with consideration of your company as a potential employer. It's also important to distinguish between perceived familiarity and accurate knowledge. People may hold a negative view of your organization because they have a misguided impression of what you or your industry does.

(b) Employer brand image

How strongly are your EVP pillars and other desired image associations perceived by your key target audiences?

To fully understand the vitality of your external employer brand image it is important to understand the strength, consistency and relative appeal of each image dimension and how it compares with your leading talent competitors.

(c) Image strength

Moderate strength of agreement scores often result from general ‘halo’ positivity if your corporate, customer or employer brand is generally well regarded. They are also more likely to result from general associations with your industry sector. To be sure your employer brand marketing efforts are getting your desired message across it is therefore important to put greater focus on the ‘top box’/‘Strongly agree’ scores.

(d) Consistency

If an organization has grown through acquisition or has operated a high degree of local autonomy, associations with the brand can vary significantly from place to place. In some cases this may remain part of the plan, but if there is a desire to establish a more consistent global brand it is important to track and measure these potential inconsistencies in order to target and rectify them. This need not conflict with efforts to tailor the EVP to local target groups. There may always be a benefit in highlighting some image attributes more than others to match local preferences; however, the primary image components of the brand should always be present and positive.

Another aspect of consistency that is important for you to consider is any potentially significant gaps between external perceptions (brand reputation) and internal perceptions (employment experience). Where external perceptions fall short of positive internal perceptions you can communicate these strengths with confidence. Where external perceptions are significantly more positive than internal perceptions, you clearly need to tread more carefully in making employer brand claims. These findings should also prompt action to address internal weaknesses that are likely to lead to post-hire disappointment and attrition.

(e) Attribute appeal

If the EVP has been developed effectively, the chosen pillars and communication themes should be appealing to your key target audiences. However, it is important to both validate and track the appeal of these image dimensions over time as they are subject to change. In addition to tracking the ongoing appeal of your chosen EVP attributes, it is also useful to keep an eye on other dimensions that you have chosen not to emphasize. It may be possible that the growing strength of appeal of a particular dimension among your target audience may prompt you to consider incorporating it into your EVP at some point, or including it in your messaging and content marketing to a particular target group.

(f) Competitor benchmarking

This will enable you to confirm and track your points of parity (POPs) and points of difference (PODs) over time. The competitive environment is constantly changing and it is vital to keep a weather eye on those areas where your relative advantage may be under threat. To preserve the vitality of your brand reputation you need to be continually strengthening and distinguishing your own offer to ensure it remains differentiated from your leading competitors. As discussed in Chapter 10, this requires a broad understanding of your relative standing in relation to general image dimensions like teamwork, innovation, autonomy and learning and career progression. However, it should also ideally include a more specific evaluation of the more specific points of difference you are communicating. This is more challenging from a research perspective as these are unlikely to be incorporated within syndicated research studies like Universum's global student survey, and will therefore require more tailored research.

Universum is the leading source of employer brand reputation data among students. They can provide company specific data relating to:

- Brand awareness

- Employer brand image (relative to key competitors)

- Drivers of employer attractiveness

- Awareness, consideration, preference and intention to apply.

This data can be tailored to the individual needs of the organization by country, competitive set and broad student target groupings (Business; Engineering; Natural Sciences and Humanities).

A number of companies, like P&G, make use of Universum to track their overall favourability and their relative standing among business and engineering students in their key markets around the world. Since they refreshed their EVP and employer brand marketing campaigns in 2008, P&G's global ranking among business students has steadily improved from 14th in 2007 to 6th in 2009, to 3rd in 2012.

(g) Tailored brand image surveys

Establishing your brand reputation among the wider target population is far more challenging. It may be possible for you to incorporate employer brand related questions into other forms of brand survey that your organization may conduct. It is now common for corporate image surveys to include a perspective on the company's reputation as an employer. Companies like McDonalds also use their customer satisfaction survey to track people's perceptions and consideration of the company as a potential employer.

(h) New joiner surveys

Represent one of the most under-used potential sources of employer brand image data. The disadvantage of this data collection method is that it will clearly not represent the broader potential target population, and there will inevitably be a positive bias. The advantage is that it should represent a highly distilled sample of the people you most want to hire. The questions you should be asking new hires are:

- What qualities did you first associate with our organization before you started looking for more information? (What does the analysis tell you about the relative strength of the EVP pillars in relation other image associations?)

- In what ways, if any, did your image of the organization change as you gathered more information? (Were EVP pillar associations strengthened?)

- Which other organizations did you consider joining? (Competitive set)

- Why did you choose to join our organization? (How important were the EVP pillars in making the decision to apply and join?)

DESIRED EXTERNAL BEHAVIOURS AND OUTCOMES

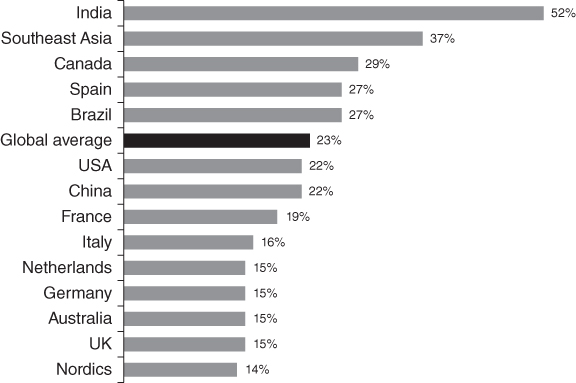

Having established measures for your employer brand reputation, it's important to determine what this image translates into in terms of desired outcomes and behaviours. Ideally, you should be able to identify a strong correlation between specific image improvements and higher levels of brand affinity, consideration and preference. If there appears to be a strong correlation between a particular brand image dimension and attraction within specific target groups, the employer brand team may consider amplifying the expression of this pillar in future recruitment communication (Figure 20.3).

Figure 20.3 Desired brand reputation and outcome metrics.

(a) Talent pool reach and engagement

Consideration and application are not the only measure of employer brand strength and recruitment marketing effectiveness. Organizations are increasingly taking a longer term view in building relationships with potential candidates. This may take the form of a proprietary talent database, or LinkedIn company profile pages and interest groups. It should be possible to create a measure of your talent pool quality by assessing the proportion of people within your identified pool who meet your overall target profile requirements for key roles.

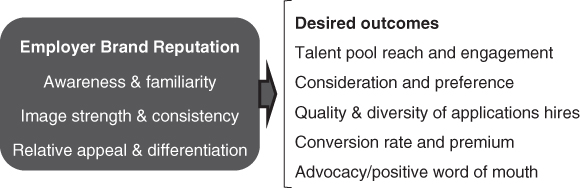

LinkedIn's Talent Brand Index tool can provide a useful measure of your current levels of ‘reach/familiarity’ and ‘engagement/active interest’ within LinkedIn's membership base (compared with your key competitors) (Figure 20.4).

Figure 20.4 LinkedIn's talent brand index.

This analysis should be combined with an assessment of other environmental factors affecting talent availability, particularly general levels of employment and recruitment activity (particularly among key competitors). When they are both high then talent will be less available and more expensive to recruit. Most governments provide data on levels of employment and unemployment. There are also a number of regular sources of hiring activity data including Manpower and LinkedIn.

(b) Consideration

What percentage of your target audience would consider you as a potential employer? If possible you should try and determine relative levels of consideration among active job seekers vs passive targets. High levels of consideration among active targets could be driven by the perception that you hire a lot of people rather than your relative merit as an employer. The true test of your employer brand equity is consideration among targets who are not currently active in seeking a job. Another good indicator is the proportion of target candidates who agree to a job opportunity conversation on the strength of your brand name.

(c) Preference

What percentage of your target audience rates your organization higher than your immediate talent competitors as a potential employer? While a high level of overall preference will no doubt be satisfying, the key question to ask is which image dimensions appear to be most important in driving this differentiation and preference? Once you've established this insight, you can then consciously feed it back into your marketing activities.

(d) Application volume, diversity and quality

Are you receiving the kind of applications you're looking for? The ultimate test of your employer brand reputation and marketing activity is their ability to generate the right volume of applications meeting your desired target profile, quality standards and diversity objectives. The ‘right’ volume means sufficient high quality applications to fill your position. Anything beyond this point results in greater time, cost and rejection, so make your KPI the optimum number not the absolute number.

(e) Quality of hire

Are you making the right hires? This measure should ideally be a natural output from the pre-hire selection process and post-hire performance management and retention data; however, only a minority of organizations appear to collect and analyse this vital information effectively. In a recent Staffing.org survey, C-level executives rated new hire quality as the most important HR performance metric out of 20 possible metrics; however, a variety of recent research surveys suggest that only between a quarter and a third of organizations track quality of hire.13

The typical components of a ‘quality of hire’ metric are:

- % Satisfying the needs and expectations of the hiring manager (HMS).

- % Meeting performance expectations within the first 12 months (PE).

- % Retained for a minimum of 12 months, or long enough to provide a return on performance, if this calculation exists (ER).

This can be translated into a quality of hire index, to judge the overall recruitment marketing effectiveness or the relative effectiveness of different channel and campaign content sources.

- Quality of Hire = %HMS + %PE + %ER

It should be noted that HMS and PE will always be subjective scores. In many organizations PE will also be rounded out over time if the company uses a distributed bell curve to rate performance (i.e. they use relative measures of performance not absolute/variable measures). Nevertheless, this calculation should still provide a useful measure of the relative contribution of different channel and content sources to the quality bench strength of the organization. To this you may also choose to measure and track whether your selection process is delivering an appropriate level of diversity among final hires.

(f) Conversion rate and conversion premium

What percentage of people accept your job offers, and at what conversion premium?

When talent markets get competitive, it is not unusual for some candidates to be receiving multiple offers, and the conversion rate (% increase in people's salary from their previous employer) can rise significantly. Your ability to convert offers into hires at reasonably low conversion rates is an important indication of the strength and value of your employer brand reputation.

(g) Positive word of mouth

How do you score in terms of positive social sentiment (likes, shares)? If your employer brand is of relevance and interest to people, they are more likely to participate in your content marketing activities and help to amplify your brand messages and reputation through sharing this content with their friends and professional contacts.

(h) Social listening

A number of companies now undertake research to analyse online mentions of their brand, what people are mostly talking about and whether their overall sentiment towards the brand is positive, negative or neutral. This can provide a useful indication of your social ‘brand footprint’ as it is sometimes called, but you need to bear in mind that most of the commentary generally comes from people within your organization rather than outsiders looking in. Some sites like Glassdoor's primary reason for existence is to facilitate this ‘insiders’ view'.

RELATIVE IMPACT OF RECRUITMENT MARKETING ACTIVITIES

The final set of metrics and analytics from an external employer brand perspective relate to the efficiency and effectiveness of your talent and recruitment marketing activities in driving your desired employer brand image and behavioural outcomes (Figure 20.5).

Figure 20.5 Recruitment marketing efficiency and effectiveness metrics.

(a) Target profile fit

How well are you defining the skills and abilities your organization requires to maximize performance, in broad terms and for key (‘pivotal’) positions and roles? In other words, are you targeting the right people? This is clearly a shared responsibility between HR and line management, and both sides should review the degree to which ‘quality of hire’ attrition and performance failings are due to poor target definition, rather than poor selection.

(b) Workforce planning accuracy

How well are you predicting the type and volume of talent you need? This can be measured more objectively by comparing advanced hiring estimates with actual hiring needs. The most important linkage in this case will be with your ‘time to hire’ and ‘time to fill’ metrics, since the better your advanced planning the more you should be able to minimize this performance downtime.

(c) Impact and influence of marketing content

How effective is your marketing in getting your message across and prompting desired behaviours? This can include measures relating to specific marketing content elements (individual adverts, social posts etc.) or combinations of content falling within a defined ‘campaign’. The most appropriate metrics for most individual content elements would be measures of engagement (comments, likes, shares, click-throughs etc.) but it may also be possible to measure direct impacts on the application rate if the execution includes this call to action. It's seldom possible to measure the impact of individual content elements on brand image, but it should be possible to do this for sustained forms of campaign activity, either though some form of tailored ad hoc survey or syndicated research, like Universum's Global Student Survey.

(d) Impact and influence of marketing media

Which of your media channels are delivering the greatest value at the lowest cost? (Table 20.2)

Table 20.2 Sources of Hire

| Total number of open positions? (including % new position vs. replacement hires?) | |||

| Posted within BU? | Posted across BUs? | Advertised externally? | |

| Filled within BU? | Filled across BU? | Filled within/across BU? | Filled externally? |

Hiring managers should ideally complete an ‘origin of hire’ record for every open position that has been filled. This would help to provide a more complete answer to the following key questions.

- How many open positions/job opportunities have been generated?

- How many of these open positions were the result of creating new roles or positions and how many were replacements?

- How many were advertised beyond the immediate business unit?

- How many were advertised externally? Of these, what proportion was filled internally?

- How many internal hires involved a move within the business unit or division and how many involved moves between business units or divisions?

- How many full-time hires were made from contract or contingent workers or interns?

Recruitment metrics have conventionally assumed that one channel can be identified as a dominant ‘source of hire’. As Gerry Crispin and Mark Mehler make clear in CareerXroads 2013 Source of Hire Survey, this form of measurement is becoming increasingly difficult. Their honest and constructive perspective on the subject is worth reading in full:

‘Today, the medium AND the message are blurred in ways we never imagined when we insisted that each hire be attributed to only one source. … It would be just as hard to imagine a hire that wasn't intertwined with multiple sources located at varying points on a stretched out recruiting supply chain that reaches from early education to talent community. Mapping how prospects navigate the early stages of the recruiting supply chain IS possible but not without significant changes in what employers currently require and accept from their technology partners.’

Rather than combining everything together into the over-simplistic term ‘source of hire’, organizations should aim to determine and differentiate between:

- Source of Awareness (Where did applicants become aware of the potential employment opportunities offered by your organization or a specific position?)

- Source of Influence (Which media or types of contact did they regard as primary and secondary sources of influence?)

- Source of Application (Which channel did they apply through?)

- (Segmented by applicant type: e.g. on-profile vs off-profile, subject to offer etc.)

To achieve this, organizations need to establish a system that is capable of recording, consolidating and validating the influence of data from multiple sources (e.g. ATS, Recruiter, IP measurement AND Self-Reports, developed with I/O expertise).

Unfortunately candidates tend to be a very unreliable source of data on their media influences. TMP Worldwide has conducted a considerable amount of research on this subject for many different clients, and has concluded in most cases that only a small minority of candidates can provide an accurate account of the media through which they have made an application when cross-checking against more objective sources of data.

Social media provide an important example of channels that may provide a strong source of influence but not register as prominently in terms of source of application. In the 2013 Career XRoads Survey respondents only attributed 2.9% of their hires directly to social media, for example; however, they also believed that social media influences, drives or combines with 7 out of 11 other sources: Referrals, Company Career Site, Job Boards, Direct Source, College, Temp-to-Hire and Career Fairs.

(e) Recruitment analytics

Given the increasingly complex nature of media interactions, it has become very difficult to conduct detailed and accurate analyses of the total marketing system; however, there are some broader areas in which a judgement of the relative cost and effectiveness of different recruitment marketing activities can be made. In recruitment as in many other areas of business it is tempting to focus on the more immediately tangible variables like cost and time rather than more complex (but ultimately more important) variables like quality of hire. Ideally you should attempt to link both types of measure to your most significant marketing decisions, so that for any major content investment or media spend, you can calculate:

- Cost per application and cost per hire.

- Time to hire and time to fill (plus the estimated cost involved in excessive position vacancy days, particularly in relation to key revenue generating positions).

- Quality of applicant and quality of hire.

In broad terms this should at least enable you to calculate the relative cost and quality of:

- Direct sourcing hires vs agency hires.

- Referral vs SEO vs Job-boards etc.

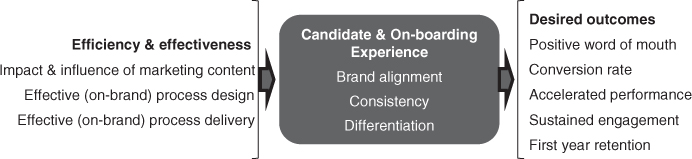

CANDIDATE MANAGEMENT AND ON-BOARDING METRICS

When it comes to talent, you cannot assume that successful applicants will necessarily take your offer of employment or, if they do, that they will stick around long enough to repay your investment in recruitment and induction. Conversion rates in some fast growing markets have been frustratingly low, even among well-known multinationals, as well qualified candidates weigh up several competing offers. Likewise, in markets all round the world there is an unfortunate tendency for employees to finish their first year at an employer far less engaged than they started it.

As discussed in Chapter 19, there are many steps you can take to ensure that you do convert the talent you want to hire and keep them engaged, but it's important to seek feedback from applicants, candidates and new joiners to ensure their experience is in line with what you intend (Figure 20.6).

Figure 20.6 Candidate experience and on-boarding metrics.

(a) Candidate experience

Companies should monitor candidates' experience of the application and selection process to ensure that it leaves a positive and professional impression. Ideally this should also include some form of image analysis to determine whether the process has reinforced the expectations of the employer brand communicated through the company's recruitment marketing. You should be aiming to leave unsuccessful candidates as positive about your employer brand as successful ones, and where suitably qualified ensure that they remain in your talent pool ready to take up more suitable positions if they arise in the future. Research suggests that the overwhelming majority of candidates reporting a positive candidate experience also claim that they would refer others to apply to the company. Given the ease with which people can now broadcast a dissatisfactory experience across their personal and professional networks, the potentially negative consequences to your employer brand are also significant. Despite the clear benefits of monitoring candidate experience, the evidence surprisingly suggests that this form of research is still only conducted in a minority of cases. Even among the 95 ‘forward-thinking’ US companies taking part in the 2013 Cande Awards survey, less than a third reported asking candidates for feedback, with only 15% percent doing so routinely.13

(b) On-boarding experience

As above, the basic tracking measures should include satisfaction with the on-boarding process and an evaluation of whether the experience reinforced desired impressions of the employer brand. Ideally, as discussed in Chapter 19, the feedback period should be extended to include the longer period of orientation that takes place over the first 3–6–12 months (depending on the importance and complexity of the role).

The three key outcome measures which should be used to determine the overall success of on-boarding and orientation are:

- Engagement. There is a tendency in many organizations for engagement levels to decline during the first year of employment. While it's understandable for the initial ‘honeymoon’ period to produce very high levels of engagement, the organization should keep track of the decay rate, and rectify sources of dissatisfaction.

- Retention. Attrition levels within the first 12 months can indicate a number of potential issues that may need to be addressed by the organization. These could include hiring people with the wrong cultural fit, significant gaps between employer brand expectations and the reality of employment, or a poor on-boarding process.

- Speed to Performance. While this can be difficult to measure, some organizations calculate how long it takes an employee to ‘get up to speed’ with their new job, and the time it takes to make a return on the investment involved in recruitment and on-boarding someone to a new position.

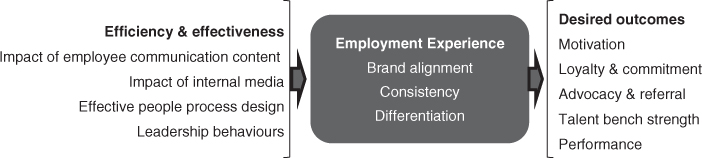

EMPLOYER BRAND EXPERIENCE

As Abraham Lincoln rightly pointed out, reputation is a shadow. The ultimate strength of an employer brand lies in the character of the organization. Marketing can amplify this character, but it can never replace it. For this reason the most essential and enduring measure of employer brand strength lies in the perception and experience of current employees, just as the health and vitality of a consumer brand ultimately depends on the consumer brand experience (Figure 20.8).

A number of leading companies have begun to measure the strength and consistency of their desired employer brand experience in the same way that companies measure the external strength of their desired brand image associations. Fortunately, it is easier to conduct this kind of research internally than externally. Most leading organizations conduct some form of employee engagement survey, and this provides a rich source of potential data for evaluating the current health and vitality of the employer brand, as well as the relative performance of priority EVP attributes in comparison to industry and high performance company norms. A similar form of benchmark measurement can also be undertaken through participation in ‘Best Employer’ surveys like those conducted by the Great Place to Work® Institute.

One of the most common approaches is to create an Employer Brand Experience Index or EVP Index. This involves adding a sub-set of questions to the overall engagement survey that specifically relate to the EVP pillars or explicit employer brand promises made by the organization. The most effective way of formulating this EVP index is to choose 2–3 questions describing the key dimensions of each pillar. Ideally, these questions should include 1–2 generic benchmark questions describing the general ‘territory’ in which the employer brand promise is made. This enables a comparison with other peer group companies to determine whether the organization's performance in relation to this dimension is distinctively strong in relation to comparative benchmarks. To this you can then add a further 1–2 more unique questions capturing the more distinctive or stretching aspects of the pillar.

The Index is simply made up of the aggregate scores from each set of pillar questions, providing one overall metric summarizing the current health and vitality of your employer brand from an employee experience perspective.

The questions below illustrate how the LEGO Group applied this thinking to calculating their EVP Index (Table 20.3).

Table 20.3 LEGO Group - EVP (People Promise) Index

| EVP Pillars | EVP Index Questions (BG = Benchmark Generic) (SD = Stretch Differentiator) |

| Purpose Driven | (BG) I am proud to tell other people where I work (SD) In my daily work, the LEGO mission strongly inspires me to do my best |

| Systematic Creativity | (BG) My present job offers me a chance to learn new skills and develop my talents (SD) In my daily work, I am highly inspired to use both my imagination and experience |

| Clutch Power | (BG) In the LEGO Group there is an environment of trust (SD) I feel part of a strong LEGO community, with an extraordinary bond among people working in the LEGO Group |

| Action Ability | (BG) My job makes the best use of my work related skills and abilities (SD) People working for the LEGO Group always take accountability and deliver what they promise |

DESIRED EMPLOYEE OUTCOME MEASURES

The term ‘employee engagement’ is the common collective term used to describe the range of employee-focused outcomes that a strong employer brand experience tends to drive within an organization. To this should be added relevant measures of employee performance, such as productivity, customer satisfaction and sales, and the overall bench strength of talent within the organization (Figure 20.7).

Figure 20.7 Employer brand experience metrics.

(a) Employee engagement

While the organizations that run employee surveys define employee engagement in a number of different ways, they tend to share a number of common components.

- Motivation. Do employees feel motivated to go the extra mile for the organization?

- Loyalty. Are employees committed to building their career with the organization?

- Advocacy. Would employees recommend the organization as a good place to work?

The most important measure from an external employer brand reputation and recruitment perspective is advocacy, since the preparedness of employees to communicate positively about their employer through social media and refer good candidates has increasingly become the bedrock of effective social marketing. The other common term used for this measure is the Net Promoter Score, which represents the net sum of positive employee advocates and negative detractors.

This Net Promoter Score needs to be kept in balance with employees' motivation to perform, as it is possible that the wrong kind of advocacy could also result from a comfortable but low performing work environment.

Some people have begun to question the inclusion of ‘loyalty’ in the definition of engagement, as it tends to be more influenced by the external context. Over recent years it could be argued that employees' intention to stay with their employers has been more influenced by the poor economic environment and a risk-adverse desire for stability, than heart-felt loyalty and commitment to their employer brand. Likewise, in fast growing emerging markets, engaged employees may still be highly vulnerable to the many alternative opportunities open to them elsewhere.

More recently, Towers Watson has introduced the concept of ‘sustainable engagement’, which includes measures of wellbeing. Given that employees can sometimes be too engaged, prone to over-work and burn-out, I believe this is a welcome addition to engagement thinking.

These engagement measures represent the desired behavioural outcomes of a strong employer brand, in the same way that application and positive word of mouth represent the desired outcomes of a strong employer brand reputation and effective recruitment marketing.

(b) Talent retention and bench-strength

Another key indicator of the success of your employer brand management efforts is your organization's ability to build and maintain a strong talent pipeline. You should be keeping a close eye on retention levels among your key job roles and high potential population as they are likely to be the most prone to competitive poaching.

(c) Performance

As demonstrated in the RBS cases study highlighted in Chapter 2, it is possible to analyse the linkage between your employer brand index, employee engagement and key performance metrics like customer satisfaction and sales. This is an extension of the ‘Service Profit Chain’ Model established by James Heskett and a number of other business academics from Harvard University in the 1990s. This should establish the same kind of performance linkage internally that quality of hire metrics establish for your recruitment marketing efforts externally.

(d) People management processes and practices

One of the most common and well established forms of talent analytics is engagement driver analysis. The majority of employee research agencies now provide this form of analysis as standard. In simple terms this enables you to identify which of your people management practices appears to be most important in driving employee motivation, advocacy and loyalty. This same analysis can be applied to evaluating the potential engagement value to be gained by improving the fulfilment of your employer brand promises.

ADVANCED ANALYTICS

Predictive analytics represents a more sophisticated approach to metrics, involving the use of statistics to better understand (and predict) the relationships between talent acquisition, management and performance. In a survey of 480 large organizations, Bersin Deloitte found that only 4% of had achieved the capability to perform ‘predictive workforce analytics’, and only 14% had conducted any significant ‘strategic analysis’ of employee data. The majority claimed to be far more operational, ad hoc and reactive in their reporting. However, the research suggested that the positive outcomes associated with taking a more advanced approach to talent analytics were significant. Those companies undertaking predictive and/or strategic analytics were also twice as likely to be delivering high impact recruiting solutions and two and a half times more likely to report healthy leadership pipelines.14

An advanced talent analytics dashboard for employer brand management should include the following key components (Figure 20.8).

Figure 20.8 Key metrics and linkages in the talent lifecycle.

You may be asking why so few companies have successfully applied advanced analytics to talent management and reaped the business benefits? According to the MIT Sloan Management Review and a survey among 300 IT professionals the answer is clear. It's because companies have failed to identify, attract and engage the right kind of analytical talent! I rest my case.15

SUMMARY AND KEY CONCLUSIONS

- The use of measurement to determine the effectiveness of different employer brand marketing activities has been relatively piecemeal in most organizations.

- The most common metrics used to measure employer brand marketing impact are employer league table rankings (Universum, ‘Great Places to Work’ etc.), employee turnover and cost per hire.

- Diagnosing and tracking your employer brand health and marketing effectiveness should extend beyond recruitment metrics to measures of internal brand perception and engagement.

- Organizations should ideally be capturing data at every stage in the talent lifecycle from identification of the potential talent pool through to fully productive employment.

- The three key categories of employer brand measurement are: brand reputation and experience; desired behaviours and outcomes; and marketing efficiency and effectiveness.

- External reputation represents a fundamental component of your employer brand equity (the inherent value of your brand). A clear and distinctive reputation represents the desired cumulative result of your past marketing efforts.

- Having established measures for your employer brand reputation it's important to determine what this image translates into in terms of desired outcomes and behaviours.

- It's important to seek feedback from applicants, candidates and new joiners to ensure their experience is in line with what you intend.

- Just as the health and vitality of a consumer brand ultimately depends on the consumer brand experience, the most essential and enduring measure of employer brand strength lies in the perception and experience of current employees.

- Predictive analytics, involving the use of statistics to better understand (and predict) the relationships between talent acquisition, management and performance, represents the next measurement frontier for many companies.