Chapter 11

Speaking and Listening Critically: Effective Learning

In This Chapter

![]() Loving lectures and succeeding in seminars

Loving lectures and succeeding in seminars

![]() Taking effective notes

Taking effective notes

![]() Doodling for success

Doodling for success

The growth of knowledge depends entirely on disagreement.

—Karl Popper

Critical Thinking is an active, questioning activity that inevitably involves speaking and listening critically. In order to communicate your own ideas and views effectively, and to appreciate and analyse those of others, you need to interact with people, hearing what they're saying and responding clearly.

In this chapter I suggest ways to make lectures, seminars, discussions and meetings, all kinds of activity where speech predominates, more productive. I discuss the pros and cons of formal lectures versus less structured methods of learning.

Despite my reservations about lectures, I include some practical strategies for getting more out of seminars and lectures and ways to extend Critical Thinking from not only what you read and write but to what you hear and even what you say.

I show how note-taking and doodling can provide the crucial missing interactive element. And don't forget, as this chapter has a polemical edge you can practise your Critical Thinking skills by weighing up the arguments I present.

Getting the Most from Formal Talks

When you're reading or indeed when you are writing, you can at least take a little time to be properly analytical and organized. Not so when you are talking! Or indeed when you are trying to keep up with what someone else is saying. This section is all about how to get straight to the heart of issues in ‘real time’ — that is, how to keep up with live arguments and debates. In the academic context of seminars and lectures. It will give you some insights into how to deal more effectively with the ideas and information presented.

Whether you're a student or teacher, an employee or a boss, you will sometimes need both to take in detailed information delivered verbally, and to explain things on your own behalf to others — perhaps individually, perhaps in groups. Most people will have been brought up with really just one model of communication — the lecture style — the one which dominates education from age five onwards. And I mean onwards, because even PhD students spend most of their time passively taking in information delivered by specialists. However, formal lectures are a very inefficient way to convey information and ideas. In the world of business, the assumption is often that if someone has been paid to give a talk, then they better do just that — and share as much of their expertise as possible in the time available (and many professors seems to think the same way). When they're essentially delivering the kind of information that the listeners can read for themselves (and where the audience is earnestly trying to put down on paper the lecturer's words) the approach becomes pretty absurd.

Good lecturers are like actors on a stage, totally aware of their audience. I've known some lecturers who even managed to perform like standup comedians, which I know sounds rather frivolous, but a lot of information can be conveyed using humour. Don't underestimate it — For Dummies critics who think that books which adopt a light tone are less informative than the ones that just plod monotonously on are wrong!

Of course, multimedia tools can boost the formal talk's usefulness. But really, the only way to keep the attention of audience members is to have a genuine interaction between them and the speaker.

Teachers often complain that their students fail to remember what they've been taught from one week to another, that they forget what was in chapter one by the time they are at chapter three and so on. More sophisticated professors may bemoan the inability of students to transfer what they've studied from one context (or problem) to another.

Yet here's a paradoxical thing. Rote learning, that is passive learning, is inefficient learning, because the brain hates disassociated information. Facts and ideas are best digested when they can immediately be put to use, which is why a well-chosen question in a lecture can help listeners to sort out what they think and both organise and retain it better. It is this ability to sort information, to create mental links between different things already learned and, most of all, to have the kind of brain ready to see new links and possibilities that Critical Thinking encourages, and for very practical reasons. Plenty of, although, to be fair, certainly not all, research studies find that lots of high-achieving students who just soak up facts and figures on no matter what, and thus excel at exams are duffers when faced with real-life issues and problems in their working lives because they have not developed the more important ‘metaskills’ of actively processing information.

Hint: you might start with a question — but what would be a good one? Or you might start with a joke or personal story — but again, what sort of joke or story would fit the context?

Participating in Seminars and Small Groups

The latest research on teaching emphasises that the best teachers say the least — though you'd hardly know it: the model of a subject expert giving a lecture is pretty hard to uproot. Thank goodness for that alternative way of learning — seminars.

- Really do any specific preparation asked for — it's only polite!

- Make a list of questions that you might expect the seminar to help you answer.

- Clear your mind of other distractions — like when to do the shopping or who to ring up later.

- Be rested, and well fed!

- At the seminar, don't try to impress, just be ‘normal’.

- And, of course, listen closely and carefully to everyone else.

Honing your listening skills

In a lecture or formal talk, listening is difficult. How do you avoid dozing off? Does taking notes count as active listening if you aren't really following the thread? Well, maybe. The thing about lectures is that very, very little of what's said goes into your memory: certainly less than 10 per cent and maybe more like 0 per cent! (And that's garbled. . . .)

That's why listening skills come into their own during seminars, where (unlike most formal lectures) you're allowed to talk. In a successful seminar, everyone listens closely, responds thoughtfully, clarifies statements and justifies their thinking. In a formal lecture, you can't keep butting in with questions, but you can ask them just the same — privately, to yourself. You can jot down queries as they occur to you — and also answer them as a scribbled note, either positively, if the meeting later seems to meet the point and satisfy your doubt, or ‘negatively’, if you think you begin to see a weakness in the position being presented. Either way, you become more active in the otherwise rather passive lecture process.

Transferring skills to real-life problems

Much of education is about preparing for what comes next after education. It's about the extent to which what you learn can be applied — transferred later. Laszlo Bock, a high-up at Google, has some interesting insights on the importance of transferable skills, saying:

One of the things we've seen from all our data crunching is that G.P.A.s [Grade Point Average] are worthless as a criteria for hiring, and test scores are worthless — no correlation at all except for brand-new college grads, where there's a slight correlation. Google famously used to ask everyone for a transcript and G.P.A.s and test scores, but we don't anymore, unless you're just a few years out of school. We found that they don't predict anything.

—Laszlo Bock quoted in ‘Head-Hunting, Big Data May Not Be Such a Big Deal’, Adam Bryant, New York Times, 19 June 2013

Yes, he really does say ‘a criteria, (instead of criterion) but you should forgive him because this is good news for people (you can't see, but my hand's in the air!) who hate having to work out which funny diagram doesn't belong in a group of funny diagrams, or pointless maths puzzles.

Here's Laszlo again:

On the hiring side, we found that brainteasers are a complete waste of time. How many golf balls can you fit into an airplane? How many gas stations in Manhattan? A complete waste of time. They don't predict anything.

—Laszlo Bock quoted in ‘Head-Hunting, Big Data May Not Be Such a Big Deal’, Adam Bryant, New York Times, 19 June 2013

. . . when you ask somebody to speak to their own experience, and you drill into that, you get two kinds of information. One is you get to see how they actually interacted in a real-world situation, and the valuable ‘meta’ information you get about the candidate is a sense of what they consider to be difficult.

—Laszlo Bock quoted in ‘Head-Hunting, Big Data May Not Be Such a Big Deal’, Adam Bryant, New York Times, 19 June 2013

Students — everyone — need less drill and practice and more opportunities to discuss things in an open-ended way, as well as opportunities to practise and apply ideas on real problems.

Noting a Few Notes

More is not always better! I hope that anyone planning to do some Critical Thinking would immediately see that taking literal notes during a lecture or maybe a class is a pretty silly idea. (For tips on taking notes when reading, which is a very different matter, see Chapter 9.)

The obvious thing is for the lecturer or teacher to prepare the key points in advance, maybe in note form, and hand them out. Simple! So how come in some colleges you often find hundreds of students sitting in a hall scratching out identical notes while a professor recycles for the umpteenth time the core curriculum?

One claim often made for this tradition is that note-taking helps people to memorise information, maybe because handwriting uses a different part of the brain to that involved in listening. But if you think about it, this is a pretty feeble justification.

- Socrates: Favoured an interactive, debating style, in which he engaged people in conversation.

- Plato: Advocated a lecture-based approach to learning.

Engaging in debate: The Socratic approach

Socrates's educational ideas drew upon the practice of the sophists, who were an early kind of thinking-skills experts offering advice to the aspirational classes for a small fee. Their main role was to show private citizens how to win arguments in the public assembly, where all the decisions of the day were decided by a kind of mass vote, whether as politicians or as lawyers.

Listening to an expert: The Academic approach

No surprise then, that whereas Socrates seems to have never written any books, both Plato and his pupil, Aristotle, left behind comprehensive libraries of their ideas and research.

So both Plato and Socrates actually agree on learning needing to be active, rather than passive, even if Plato is heavily into delivering expert opinions too. Plato's dialogues are actually a radical kind of note-taking in themselves — the short plays are Plato's way of recording facts and views about his favorite great philosophers, with his personal insights added in.

Comparing the consequences for the note-taking process

Plato lived nearly 2,500 years ago, but his ideas have had a huge incluence over the form education and learning has takenn in universities and colleges ever since (take a look at the nearby sidebar ‘Socrates and Plato go to school’).

As a result, in modern universities students sit quietly through lectures or read set texts (books or handouts) in order to reduce them to notes; later they write essays. As you can see, Plato's Academic approach has won an almost total victory over that of his master, Socrates.

But in real-life situations where taking notes is a useful skill — perhaps during a meeting where new ideas are being generated or previously unappreciated differences of opinion (perspective) clarified — notes are definitely going to be a mix of fact and interpretation. Plus these days, unlike in the days of the Ancient Greeks, people have access to all the background facts — often very speedily too, via the Internet. For more locally specific information the lecturer really ought to copy and hand out the data. Either way, time spent, say, recording grape yields in Aquitaine, France, 1960–69, or titles of pop songs with numbers in them, is wasted time.

Smart note-taking, as opposed to the desperate and sometimes obligatory scramble to get everything down before the page changes — when a teacher lacking Critical Thinking skills is in charge — is all about selection, and selection is all about making judgements. Guess what: in many contexts, the decision about what's worth noting, or the reformulation of what's said, is highly subjective and very political.

Democratising the Learning Environment

Bias often operates in business meetings and in organisational structures — and can easily result in good ideas being lost. Awareness of, and paying attention to, the risk of all kinds of cognitive biases or dodgy mental shortcuts in meetings where decisions get made, is a pretty valuable Critical Thinking skill.

- Create the right atmosphere: How many times do meetings reach bad decisions because participants are unable or too fearful to contribute? Fear stalks the classroom much as it does the boardroom. Where a hierarchy exists, people such as teachers or CEOs can make an important contribution by demonstrating their willingness to be found wrong and to change their views on matters. The level of a discussion is raised by the participants’ courage to express their convictions, no matter how unusual they may be.

- Ensure a mix of views: In areas where controversy is part of the game, have two or three different sets of facts — different proposals, different expert witnesses. But this also means a mix of roles, of personality types (including some cautious people alongside some enthusiasts and definitely some outside-the-box thinkers — the people who tend to disagree with the majority). They may not be right but they ensure that the meeting hears a wider range of views. If you can't see anyone obviously like this, give someone the role and make it their job!

- Prepare the key facts and background: In a college context, this means homework! In a business context, it means due diligence, preparing briefing notes and background papers for all the participants to have and refer to. Most real-life decisions are based at some point on reference to factual data, and it makes sense to ensure that this material is as accurate, up-to-date and complete as possible.

- Get everyone involved: At the outset, ask everyone to write down their initial positions, or maybe use a white board to ask everyone for their ‘balance sheets’ of pros and cons. This process increases the likelihood that people actually consider changing their positions later!

Doodling to generate creativity

What did Einstein, Thomas Edison and Marie Curie have in common? Yes, they were all physicists, but the answer I'm looking for is that they were all inveterate doodlers!

Anyway, that's the claim of people like Sunni Brown, who has popularised the doodle in some bestselling books. In fact, she's a ‘visual-thinking skills’ expert, who runs workshops for businesses such as banks, retailers and television networks. What she says to the executives is that doodling:

- Boosts comprehension and recall

- Allows you to organise information in novel ways with increased clarity

- Doesn't require any skill at drawing.

(That's why those little For Dummies icons are more than text decorations.)

To be honest, doodling does require some drawing skills and that's why most people give it up (along with being told off repeatedly by teachers, of course). For most teachers, doodling is associated with not concentrating, and that's the mark of a duffer, not an innovator. But even teachers can't know everything.

And that's the key thing about doodling — it uses parts of the brain that you're not actually aware of. In fact, the word means ‘scribble absentmindedly’, which sounds bad until you appreciate how incredibly subtle the mind is. Language taps only a tiny proportion of the power of the human mind and, doodling can draw on some of the rest. That's why some of the researchers have advocated that doodling be recognised as a key element in education, up there in value with reading, writing and joining in group discussions!

So just for fun, grab a pen, use the margin of this book — and doodle about the value of doodling. I'll have a go too, and you can see my effort in the ‘answers’ at the end.

Answers to This Chapter

The great intro

Of course, there's no one answer to this, but here are some general points that may be of help to you in deciding how promising your idea really is.

Start with a personal story — yes, these can be powerful and grab attention. Sad but true, a ‘horror story’ about a bad presentation probably gets the most interest!

Joke — In fact, a horror story about a bad presentation is a kind of joke — but be careful with this approach. Maybe you will accidentally step on some toes with the professor in the corner of the room — or maybe you will make yourself sound conceited. Plus, as every stand-up knows, being half way through a joke that your audience finds unfunny is an uncomfortable place to be.

Ask a question — well, this is a pretty direct way to engage with an audience. You might say, for example, ‘How many people here have ever given a really duff presentation?’ Questions like this might at least grab attention! However, you need a good follow-up; this would be back to ‘telling a story’. The kind of question to avoid is the boring one. It's incredible how often the same question comes up over and over again. So don't start by asking ‘How many of you have had experience at giving a presentation?’

Doodling on doodling

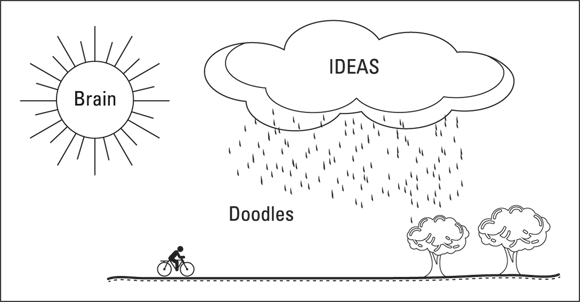

Figure 11-1: My doodle.

Okay, it's not great art. In fact, it's not art at all. But that's the point though — doodles aren't supposed to be. I let my hand do the thinking and it came up with this image that I can now see says that doodles are a way to make ideas come down out of the sky and maybe grow into useful things, like trees.

But the formal talk or lecture does have its role, which is when the talk goes beyond a written document. The most important way to achieve this goal is to be interactive and responsive.

But the formal talk or lecture does have its role, which is when the talk goes beyond a written document. The most important way to achieve this goal is to be interactive and responsive. Why do students do this? In fact, the fault may lie more with the teachers than the students. Most learning follows a hierarchical model where knowledge is delivered by an expert to students who're supposed to record it passively on paper and ideally commit it to memory later (certainly before the exam!).

Why do students do this? In fact, the fault may lie more with the teachers than the students. Most learning follows a hierarchical model where knowledge is delivered by an expert to students who're supposed to record it passively on paper and ideally commit it to memory later (certainly before the exam!). Suppose that you have to give a 5-minute presentation on the topic ‘Effective Communication’, in the context of leading a student seminar. Obviously, you'll need to practice what you preach! So what would be a nice entertaining way to start off the presentation?

Suppose that you have to give a 5-minute presentation on the topic ‘Effective Communication’, in the context of leading a student seminar. Obviously, you'll need to practice what you preach! So what would be a nice entertaining way to start off the presentation? A smart tip for making the most of academic seminars is to participate in the pre-seminar activities — nothing too racy mind, more like reading the set texts or researching the topic. Remember the Scout motto: be prepared! So how do you get the most out of a seminar or similar small group discussion? Of course, the short answer is to be prepared, but quite what preparation is, depends entirely on the context. However, some general advice I have for seminars would be:

A smart tip for making the most of academic seminars is to participate in the pre-seminar activities — nothing too racy mind, more like reading the set texts or researching the topic. Remember the Scout motto: be prepared! So how do you get the most out of a seminar or similar small group discussion? Of course, the short answer is to be prepared, but quite what preparation is, depends entirely on the context. However, some general advice I have for seminars would be: The Socratic technique was, naturally enough, to engage people in debate — a process he often categorises using military or sporting analogies. The idea is that people learn best how to win arguments by trying to win arguments with a master. When eventually they can hold their own, they've been trained. The Ancients saw reading and writing as secondary activities that weren't much use for honing these argumentative skills or for improving the reasoning that makes arguments persuasive.

The Socratic technique was, naturally enough, to engage people in debate — a process he often categorises using military or sporting analogies. The idea is that people learn best how to win arguments by trying to win arguments with a master. When eventually they can hold their own, they've been trained. The Ancients saw reading and writing as secondary activities that weren't much use for honing these argumentative skills or for improving the reasoning that makes arguments persuasive.