Chapter 9

Monitoring Trade

Steps in the International Trade Process

An analyst or investigator charged with identifying TBML is fortunate to be assisted by a wide variety of data and documentation generated throughout the international trade process. (Underground informal value transfer systems are sometimes another story!) Trading parties generally follow identified, accepted, and almost sequential steps that create a data and paper trail that can be used in spotting suspicious behavior and anomalies.

As noted in the preface, this book will not delve into the intricacies of trade finance. This includes the issuance of letters of credit, lending to import–export companies, guarantees and pre-export financing, supporting companies in the process of collections, discounting drafts and acceptances, and offering services such as credit and other information on buyers.1

The following is a brief overview of a typical trade transaction so the reader can understand where information might be available and the kind of data that are generated for analysis. Of course, the trade process varies, depending on whether it is an arm's-length transaction (as discussed in Chapter 7), and whether they are engaged in an extra-business relationship, have completed previous transactions, or are involved with some sort of trade fraud or TBML conspiracy. The terminology and trading steps also vary somewhat by market. An explanation of additional terms commonly used in the trade process is found in the Glossary.

- Export promotion—Exporters often promote their goods through sales representatives, a variety of media, the web, communications systems, and trade exhibitions, both at home and abroad. Promotion can also take place through commercial officers assigned to embassies, chambers of commerce, trade associations, and other business organizations.

- Letter of inquiry—An interested importer sends a letter of inquiry to the exporter or to the exporter's representative that generally contains a request for a price quote, product specifications, quantity, availability, and delivery details including the destination port.

- Offer sheet—In response to the letter of inquiry, the exporter sends the importer an offer sheet containing the requested information and perhaps a sample product.

- Purchase order (P/O)—If the offer sheet is acceptable, the importer will place an order via a form or letter called a purchase order. It is sometimes called an order sheet.

- Invoice—The exporter prepares an invoice or a sales contract based on the information in the offer sheet and purchase order; details of the purchase contain the identifying information of the product, shipment date, transshipment details if any, inspection, packing and marking details, and cargo insurance. The sales contract is signed by both the exporter and the importer and each side maintains a copy.

- Payment—There are various ways for the importer to make payment. Letters of credit (L/Cs) are among the most secure instruments available. An L/C is a commitment by a bank on behalf of the buyer that payment will be made to the exporter provided that the terms and conditions on the purchase order and contract have been met. Generally, verification occurs through the presentation of all required documents. An L/C is useful when reliable credit information about a foreign buyer is difficult to obtain, but the exporter is satisfied with the creditworthiness of the importer's foreign bank. An L/C also protects the buyer since no payment obligation arises until the goods have been shipped or delivered as promised. Other payment options include cash-in-advance, documentary collections, and open account.

- Shipment process—After receiving LC confirmation, the exporter readies the goods for shipment and, if necessary, retains a shipping company or freight forwarder. A number of documents are prepared by those involved directly or indirectly in the transaction:

- Bill of lading—A document signed by a carrier (transporter of the goods) and issued to a consignor (the shipper of goods) that confirms the receipt of the goods for shipment to a specified destination and company or representative. A bill of lading is, in addition to a receipt for the delivery of goods, a contract for their transport and their document of title. The bill of lading describes the method of freight, states the name of the consignor and the provisions of the contract for shipment, and directs where and to whom the cargo is to be delivered. There are two basic types of bills of lading. A straight bill of lading is one in which the goods are consigned to a designated party. An order bill is one in which the goods are consigned to the order of a named party. This distinction is important in determining whether a bill of lading is negotiable (capable of transferring title to the goods covered under it by its delivery or endorsement). If the terms provide that the freight is to be delivered to the bearer of the bill, or to the order of the named party, the document of title is negotiable. In contrast, a straight bill is not negotiable.

- Shippers export declaration or (SED)—An SED is a document used in some jurisdictions when the value of the commodity requires an export license for shipment from the country of export to another country. In the United States, the SED is used for developing export statistics and for export control purposes. The SED imparts general information about a transaction, including the parties involved, the date of exportation of the shipment, consignees and agents for the shipment, classifications, weight, and the value of the goods. The SED is signed by the exporter or the authorized agent.

- Destination control statement—This document is required only by certain countries (including the United States) for the export of commodities such as munitions and sensitive technology that requires a license or a license exemption.

- Certificate of inspection—The certificate of inspection is prepared by the seller or an independent inspector designated by the buyer that is a statement providing evidence for the characteristics of the goods.

- Certificate of manufacture—This document is from the producer of the goods. It describes the goods, states that the production of the goods is complete, and that the goods are at the buyer's disposal.

- Insurance document—This certifies that the goods are insured for shipment.

- Export license—A document issued by a government agency authorizing the export of certain commodities to specified countries.

- Import license—A document issued by a government agency authorizing the import of certain commodities into the buyer's country.

- Clearance—After receiving the appropriate shipping documents listed above, the importer or consignee secures import clearance by customs in the destination port. The importer will later contact the shipping agent in the destination port to receive the goods.

- Delivery—The shipping agent surrenders the cargo/goods to the importer.

Information Sources

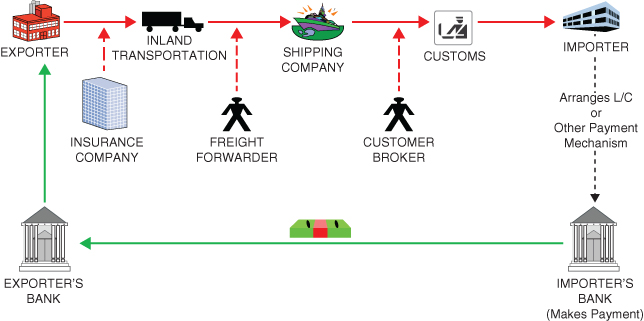

Much useful information and data are generated in the international trade process. In addition to the buyer (importer) and the seller (exporter), the reader can see in Figure 9.1 that there are additional players that can also be valuable information sources. Similar to assembling the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle, the analyst, investigator, or concerned compliance officer assembles as much information as possible to follow the value trail. The intelligence generated provides authorities data to monitor trade and to spot anomalies that could be indicative of customs fraud, TBML, value transfer, and/or underground finance.

Figure 9.1 Basic trade transaction

Over the course of my career, I found that there are four very broad categories of information that have proved particularly valuable in combating TBML. They are not found in isolation and often overlap. They are used both in examining the non-price characteristics of a transaction (such as investigator and analyst assessments and company know-your-customer policies) and in evaluating the more quantifiable elements and risk of a particular transaction.

- Human source information. As a former intelligence and law enforcement officer, I know firsthand that there is no substitute for human intelligence (humint) to provide inside information regarding a trade conspiracy. Human sources can provide tips that might point an investigator in the right direction, provide documents (officially or unofficially) that facilitate following a money and/or value trail, and perhaps explain the intricacies of the trade process, industry, and parties involved. The ideal is if the source has direct or personal access to a TBML conspiracy. Sources can be found both within and outside of the parties illustrated in Figure 9.1.

- Financial intelligence. Generally speaking, both the importer and the exporter work with a financial institution or institutions. Trade financing documents are produced. Banks and some involved money services businesses also generate financial intelligence. In TBML, the filing of suspicious activity reports (SARs), generally known outside the United States as suspicious transaction reports (STRs), can be very helpful. For example, according to Treasury's FinCEN, “over 17,000 SARs reporting potential TBML activity that occurred between January 2004 and May 2009 reported transactions that involved in the aggregate over $276 Billion.”2

FinCEN believes that SAR filings on suspected TBML are increasing.3 However, many financial institutions are just becoming aware of TBML in all of its varied forms, and they may see only a partial bit of information related to a suspect transaction.

As a former consumer of financial intelligence, I wholeheartedly concur with FinCEN's advice that “financial institutions check the appropriate box in the Suspicious Activity Information section of the SAR form and include the abbreviation “TBML” or “BMPE” (or any other identified TBML methodology) in the narrative portion of all relevant SARs filed. The narrative should also include an explanation of why the institution suspects, or has reason to suspect, that the customer is participating in such activity.”4

- Documents generated by the parties involved in the trade transactions. The parties involved in the international trade process generate paper or electronic documents. Some of the information is restricted, privileged, or available only through the use of a customs or criminal subpoena. However, quite a bit of data are now in the public domain.

In every country, concerned government agencies and departments also track trade. As noted earlier, this is done for a variety of reasons, including national security, revenue, the promotion of commerce, analysis, etc. Much of the data are in the public domain. In the United States, the Foreign Trade Division of the U.S. Census Bureau produces USA Trade Online (https://usatrade.census.gov/). A user can access “current and cumulative U.S. export and import data for over 9,000 export commodities and 17,000 import commodities.” The data are based on the Harmonized System (see below), and analytic programs allow customers the opportunity to create reports and charts detailing foreign trade variants including: port level detail, state exports and imports, balance of trade, method of transportation, and market level ranking.5

Commercial services also are available that allow inquiries from bank compliance officers and other interested parties into a particular commodity's generally accepted price. These services will provide an alert if the sales price represents a significant discrepancy off the global market price of similar goods.

- The Harmonized Commodity Description and Coding System. This is sometimes simply known simply as the Harmonized System, or HS. It was developed by the World Customs Organization (WCO). The HS comprises about 5,000 commodity groups, each identified by a common six-digit code. Countries are allowed to further define commodities at a more detailed level than six digits, but all general definitions must be within the six-digit framework. The HS is supported by well-defined rules to achieve uniform classification. The system is used by more than 200 countries as a basis for their customs tariffs.6 For purposes of monitoring trade, the data generated is useful for the kind of comparative analysis and the identification of trade anomalies discussed throughout this book.

The HS is also extensively used by governments, international organizations, and the private sector for many other purposes, such as determining trade policies, the monitoring of controlled goods, taxes, transport statistics, price monitoring, quota controls, and various types of research and analysis. The HS is thus a universal economic language. Indeed, more than 98 percent of the merchandise in international trade is classified in terms of the HS.7

In the United States, the Harmonized Tariff Schedule (HTS) was enacted by Congress and made effective on January 1, 1989. The HTS replaces the former Tariff Schedules of the United States. Export codes (which the United States calls Schedule B) are administered by the U.S. Census Bureau and Commerce Department and used to collect and publish U.S. export statistics. Import codes are administered by the U.S. International Trade Commission (USITC). However, only the Bureau of Customs and Border Protection (CBP) within DHS is authorized to interpret the HTS, to issue legally binding rulings on tariff classification of imports, and to administer customs laws.8

All U.S. imports and exports are documented on CBP form 7501 (Entry Summary) and U.S. Department of Commerce form 7525 (Shipper's Export Declaration—SED).

The HTS is based on the HS administered by the WCO. The 4- to 6-digit HS product categories are further subdivided into 8-digit rate lines unique to the United States that provide further specificity and 10-digit nonlegal statistical reporting categories. There is an HTS code number for every physical product traded from wheat to helicopter spare parts.

There are more HTS numbers than Schedule B export numbers. This reflects the greater amount of detail and scrutiny on products imported into the United States. Though matched at the 6-digit HS level, Schedule B and HTS codes for products may not be the same up to the 10-digit level. The government urges parties involved with filing import or export records to use the correct classification system, which can be easily found using online queries. U.S. HTS codes were revised in 2012. The next revision is scheduled for 2017.9

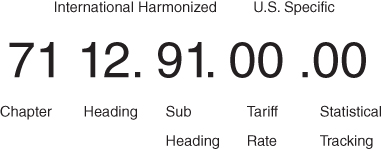

The codes are currently divided into 22 sections and 99 chapters. They begin with the least sophisticated trade goods such as animal and vegetable products. The codes reflect greater sophistication in the higher chapters covering such things as textiles, manufactured goods, computers, aircraft, and so on. A sample HTS code is reflected in Figure 9.2.

Figure 9.2 HTS sample code number for gold scrap

The gold scrap code is found in Section XIV of the HTS Code—Chapter 71: “Natural or Cultured Pearls, Precious or Semiprecious Stones, Precious Metals, Metals Clad With Precious Metal, and Articles Thereof; Imitation Jewelry; Coin.”

Description: “Gold waste and scrap, including metal clad with gold but excluding sweepings containing other precious metals.”

Note: In some instances, further specificity is detailed in the last four digits of the 10-digit code.

Using HTS data, it is fairly easy to monitor trade. For example, Table 9.1 tracks the top exports from the United States to Country X over a given period of time. The descriptions and terminology are taken directly from a computerized printout. The items are classified by HTS number, description, and value. While this type of macro data might be interesting if a specific type of import does not make market or economic sense, real analysis involves drilling down into the product categories to identify the parties involved and specific transactions. In this way, anomalies or suspicious transactions can often be identified and further action taken.

| HTS | Commodity Description | Value |

| 1001902055 | Wheat and Meslin, except Seed | $237,275,300 |

| 8703230321 | Passg Vehicle: Used; >1500<3000cc | $112,791,186 |

| 8803300050 | Air, Helicopter parts | $106,681,778 |

| 1005902030 | Yellow Dent Corn (Maize), U.S. | $83,389,530 |

| 8803300010 | Air, Helicopter parts, other; civil | $76,273,523 |

| 1006309020 | Rice, oth med gr sem/whol milld | $69,942,544 |

| 8802300070 | Milt Aircrft>2000<1500 kg | $66,238,000 |

| 4703210040 | Coniferous bleached woodpulp | $47.439,503 |

| 1001100090 | Wheat/meslin-durum wheat other | $42,752,470 |

| 1551521000 | Corn (Maize) | $42,543,754 |

| 8703240075 | Pas Vehc: New>3000cc, eng>6cyl | $34,194,965 |

| 8525203055 | Radio transceivers | $29,778,553 |

| 2403100060 | Smoking tobacco | $23,093,527 |

What about Weight Analysis?

Although most analysis of TBML focuses on price, unit analysis of weight can sometimes provide some interesting insights. For example, Dr. John Zdanowicz, an early pioneer in examining TBML, has studied the interquartile or the midrange statistical dispersion of weight characteristics of thousands of U.S. trade transactions. Table 9.2 lists a few examples of actual import weights. Dubious weight/unit anomalies are easily identified. Weight analysis can also be useful in determining possible threats.

| Country | Product | Weight |

| Egypt | Razors | 15 kg/unit |

| Indonesia | Coffee | 1.26 kg/kg |

| Germany | Sweaters | 57 kg/dozen |

| Malaysia | Briefcases | 98 kg/unit |

| Pakistan | Fabric | 2 kg/sq meter |

| Indonesia | Pillows | 55 kg/unit |

| Pakistan | Dish towels | 2 kg/unit |

Of course, similar to unit/price analysis, the possibility always exists that individual data were erroneous, inputted incorrectly, or reflected statistical outliers or deviations. With TBML, generally analysis is possible because data exists. If an anomaly or suspicion is discovered, it should be treated as a starting point or an indicator. Good decision making is about understanding the data; there is no substitute for investigation. And particularly with abnormal weights for shipments transiting sea, land, or airports, abnormal weights could well have smuggling or national security implications.

A striking example of how suspect weight can trigger an investigation occurred in Canada. A criminal organization prepared a relatively small shipment of scrap metal, but indicated that it weighed several hundred tons. As discussed in this book, fraudulent invoices, bills of lading, and other documents were prepared supporting the shipment. However, when the cargo was loaded onto the ship, an alert Canadian customs officer noticed that the hull of the ship was riding well above the water line. If the ship was actually carrying the weight indicated, the ship would have been low in the water. As a result of the observation, the cargo was examined and an investigation pursued. It was assumed that the inflated value of the invoice as supported by the fraudulent weight of the shipment would have been used to transfer illicit funds to Canada.12

The HS has revolutionized the tracking of trade. Unfortunately, many (primarily underdeveloped countries) customs services have lacked the wherewithal and expertise to take advantage of the data generated. The Automated System for Customs Data (ASYCUDA) is a computerized system designed by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) to administer a country's customs. Today, ASYCUDA is used in over 90 countries and territories.13 The goal was to construct an analytic system to assist customs authorities all over the world to automate and control their core processes and obtain timely, accurate, and valuable information. The software does not have a robust analytic component and is largely focused on automating basic transaction-processing systems involved with the day-to-day clearing of cargo. When applied to customs enforcement, it focuses largely on day-to-day interdiction—not the long-term patterns and trends generally associated with TBML.

Pioneering Analysis in TBML

In the early to mid-1990s, Senior Special Agent Lou Bock of the U.S. Customs Service became the “godfather” of TBML via his pioneering efforts to systematize the analysis of trade data to spot trade fraud, money laundering, and other financial crimes.

Lou was a former DEA inspector who had transferred to Customs. He had a rare combination of gifts that were enhanced by street-level investigative experience, coupled with his self-taught knowledge of computer programing. Lou was an incredibly bright, talented, and motivated agent. Despite a minuscule budget, working from Customs headquarters, Lou and a few colleagues tried to systematically examine trade data—specifically concentrating on spotting anomalies in trade transactions primarily using the HS and other data described above.14

With the help of Mark Laxer, a talented computer programmer, Lou was the driving force behind the creation of an innovative analytics program called the Numerically Integrated Profiling System (NIPS). Lou realized that most of his colleagues would accept only straightforward and user-friendly analysis—in other words, NIPS had to be “agent proof.” So he provided technically challenged analysts and investigators (like myself) a new type of tool that would process large amounts of data, analyze it, and point to promising targets of investigation. The end result was in a user-friendly format that included graphics and visuals.

NIPS revolutionized trade analysis for criminal investigators. It let Customs do in a matter of keystrokes what it used to take countless days of legwork and the manual review of paperwork to do—analyze massive amounts of data to look for patterns or anomalies. For the first time, NIPS routinely enabled 100-gigabyte searches of trade data—or the equivalent of manually scouring through roughly 30 million full, single-spaced pages!15

The data NIPS analyzed originated primarily from U.S. trade and financial data. At the time, much of the export data consisted of information compiled from outbound manifests that originated from commercial sources. Import data came primarily from Customs' Automated Commercial System (ACS) and import summary forms. On occasion, Lou was given access to limited foreign trade data from partner countries concerned about specific trade fraud allegations involving the United States.

NIPS used a drill-down method of analysis; the user would start with a general query such as “gold imports from the Dominican Republic.” The user would then follow up with a continuing series of narrowing queries until a likely target of investigation was reached. Using analytical parameters, later versions of NIPS could automatically spot trade anomalies and discrepancies in trade transactions such as overvaluation or undervaluation, suspicious quantities, and suspicious countries of origin. The queries also overlapped with other databases that tracked the movement of money and people into and out of the United States.

Lou built into NIPS questions that every analyst and investigator should ask: who, what, when, where? However, then as now, even if an anomaly or likely target is identified, it is still up to the street investigator to find the answers to the two other important questions: how and why?

Lou's pioneering work was buttressed by simultaneous work conducted by two academics from Florida International University. They entered U.S. Department of Commerce international trade statistics into a computer program in an attempt to find interesting international trade patterns, but in the process found glaring inconsistencies in the pricing of some of the trade transactions. Similar to Lou's analysis, the professors concluded that money launderers were hiding illicit proceeds and transferring illicit value in the enormous world of international trade.16

Trade Transparency Units (TTUs)

While Lou was busy in Customs headquarters developing NIPS, at the same time I was assigned overseas to the American Embassy in Rome helping our Italian counterparts battle organized crime (the Mafia) by examining the flow of dirty money moving between Italy and the United States. Since our Customs Attaché office in Rome had regional responsibilities, I frequently traveled to numerous countries in the Middle East, sub-Sahara Africa, and parts of Europe pursuing a wide variety of customs investigations.

Through investigations into international criminal conspiracies and the development of excellent reporting sources, I gained a unique overseas perspective. And wherever my travels and investigations took me, I always seemed to bump into the misuse of international trade. I became increasingly concerned with trade fraud's overlap with international money laundering and underground financial systems.

In documenting my source debriefs and observations about the overlap between trade and money laundering in reports and memoranda to headquarters, I began using the term trade-based money laundering, or TBML. I believe that was the first use of the term. I did not realize I was coining a now well-known description. I simply felt a new classification of money laundering was needed. At the time—prior to September 11—both the FATF and U.S. policymakers concentrated their efforts on money laundering primarily associated with the “War on Drugs” where large amounts of dirty money sloshed around through Western financial institutions. Value transfer via trade was almost completely off their radar screens.17 Because of my customs background and overseas vantage point, I felt strongly that we also needed to focus on a separate international money-laundering threat based on trade.

Lou's pioneering analytical work soon came to my attention. I became an early fan and supporter. Unfortunately, Lou's important work was handicapped by insufficient funding and the ebb and flow of high-level managerial support. In 1996, I departed Rome and transferred to FinCEN as the U.S. Customs liaison. I'm grateful for my experience at FinCEN because it allowed me to pursue my interest in international money laundering. I also gained additional exposure to the craft of analysis. Moreover, at the time, FinCEN management encouraged me to follow my interest in TBML, the misuse of the international gold trade, and study of underground financial systems. I took an active part in U.S. delegations to the FATF and I assisted in the growth of the Egmont Group of Financial Intelligence Units (FIUs), or foreign FinCENs.

During the period surrounding September 11, FinCEN management changed. The new management team insisted that similar to the dirty money battlefields in our War on Drugs, the new financial frontlines in the War on Terror Finance would evolve around the same kind of financial intelligence primarily produced by Western financial institutions. I doubted the efficacy of this approach. Moreover, I had severe philosophical and stylistic differences with the new FinCEN management team. I obtained a transfer to the Money Laundering Section of the Department of State's Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs (INL).

Shortly thereafter, I had the conversation with the Pakistani businessman I described in the Preface. His admonition that our enemies were laughing at us as they were transferring money and value right under our noses infuriated me. I subsequently discussed the issue with the head of the Indian customs service assigned to the Indian embassy in Washington D.C. We were mutually concerned about trade's link to underground finance and underground finance's link to terror. That evening, on a metro ride back home, I developed the concept and coined the term Trade Transparency Units, or TTUs.

It's a simple idea. Borrowing from the financial intelligence unit (FIU) model that examines suspicious financial transactions and other data, I suggested that the U.S. government examine the feasibility of establishing a prototype unit that collects and analyzes suspect trade data and then disseminates findings for appropriate enforcement action.

The objective was to establish a new investigative tool for customs and law enforcement that would facilitate trade transparency in order to attack entrenched forms of TBML, value transfer, customs fraud, and tax evasion. I hoped that it could also be a sorely needed “back door” into underground financial systems such as the BMPE and hawala that are being exploited by criminal organizations and terrorist adversaries. Coming from FinCEN, I hoped that one day there would be a worldwide TTU network that would be somewhat analogous to the Egmont Group of FIUs. (I also thought it important that we learn the lessons of the administrative and managerial mistakes of FinCEN and Egmont. The TTU network has to be enforcement oriented and directed.)

The wonderful thing about TTUs is that the data already exist. There is no need for vast new expenditures or to jump through labyrinths of bureaucratic hoops and approvals. As the reader has seen, every country already collects import and export data and often associated information. By comparing targeted trade transactions, it is a fairly straightforward analytical process to spot suspect trade anomalies. I knew the United States could simply build on Lou Bock's pioneering work. And I was confident that the concept would be attractive to other countries as well. Even for those that only paid lip service to fighting TBML and underground finance's link to terror, all governments are interested in combatting customs fraud and illicit value transfer because it robs them of needed revenue.

The State Department's Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs wholeheartedly endorsed the TTU initiative (and later provided funds to jumpstart the program in countries of concern). Likewise, the Department of Treasury provided crucial bureaucratic support. But the TTU initiative almost by definition dealt with trade and so had to be adopted and implemented by Customs. My former Customs colleagues, including Bock, fully supported and further developed the idea. I formally proposed the initiative in May 2003. (A copy of the original TTU proposal is included in Appendix B.) However, the suggestion overlapped with the creation of the new Department of Homeland Security and the dismemberment of Treasury Enforcement. It took a painfully long time for the government's stars to align and for sufficient resources to be devoted to finally initiate the TTU program.

The world's first TTU was established within ICE's headquarters. The NIPS program evolved into a specialized ICE computer system called the Data Analysis & Research for Trade Transparency System (DARTT). Containing both domestic and limited foreign trade data, the computer system allows users to see both sides of a trade transaction, achieving trade transparency. Other investigative and financial databases were added, giving the analyst and investigator a more complete picture of a possible criminal conspiracy. In short order, the TTU concept proved itself. Countries collaborated and made a number of successful cases.

By 2007, the U.S. government made trade transparency and TTU development part of its National Anti-Money Laundering Strategy Report. Signed by the Secretaries of Treasury and Homeland Security, and the Attorney General, the strategy committed the United States to “attack TBML at home and abroad.” Further, it promised, “Law enforcement will use all available means to identify and dismantle trade-based money laundering schemes. This strategy includes infiltrating criminal organizations to expose complex schemes from the inside, and deploying ICE-led Trade Transparency Units that facilitate the exchange and analysis of trade data among trading partners.”18

Over the last few years, the TTU has evolved into an ongoing national investigative program for HSI. The program is embedded within the National Targeting Center—Investigations. According to Hector X. Colon, the director of the TTU, “Co-locating the TTU with Customs and Border Protection's targeting teams has better equipped HSI and CBP to successfully target, investigate, and dismantle transnational criminal organizations involved in TBML.”19

The core component of the TTU initiative is the exchange of targeted trade data with foreign counterparts, which is generally facilitated by existing Customs Mutual Assistance Agreements or other similar information-sharing agreements. HSI/ICE is the only U.S. law enforcement agency capable of exchanging trade data with foreign governments to investigate international trade fraud and associated crimes.

By 2015, the HSI/TTU developed information-sharing partnerships with 11 foreign countries: Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Colombia, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Guatemala, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, and the Philippines.20 Many other countries have shown interest in participating. They recognize the value of sharing trade data with the United States and possibly other TTU partners and gaining the analytical tools and expertise to more effectively examine their own data. By combining international efforts, the analysts and investigators can effectively follow the money and value trails.

In any government program dealing with data and analytics, there are justified concerns about privacy and international information sharing. So it is important to understand that foreign government partners that have established TTUs enter into a negotiated Customs Mutual Assistance Agreement or other similar information sharing agreement with the United States. They are granted access to specific trade datasets to investigate trade transactions, conduct analysis, and generate reports in the HSI TTU trade data subsystem.

HSI has two versions of their analytic program FALCON-DARTTS: one for HSI's foreign partners with access only to trade data shared pursuant to international information sharing agreements, and another for HSI users, which contains appropriate data from TTU partners as well as financial data and other law enforcement data. Foreign users do not have access to the HSI TTU financial and law enforcement datasets. Foreign users can only access trade data related to their country and the related U.S. trade transactions, unless access to other partner countries' data is authorized via information sharing agreements. Moreover, depending on the agreement and specific investigation, the data are aggregated and specific identifiers removed.22

According to Colon, “Most countries do not have access to foreign trade data to compare imports and exports and many countries' Financial Intelligence Units (FIUs) lack access to trade data or the expertise in identifying anomalies in trade transactions. The analysis of the trade data exchanged with foreign partners is facilitated by FALCON-DARTTS, an investigative tool that allows investigators and analysts to generate leads and support investigations related to TBML, smuggling, commercial fraud, and other crimes within the jurisdiction of HSI and foreign customs organizations. FALCON-DARTTS analyzes trade and financial data to identify statistically anomalous transactions that may warrant investigation.23

The Application of Big Data and Analytics

Over the last 10 years, there has been an explosion of “big data” and analytics. Nobody knows how much data and information are out there, but former Google CEO Eric Schmidt has claimed that we now create an entire human history's worth of data every two days!24

Data alone are not that interesting. We need the knowledge that can be derived from the data. So we are fortunate that concurrent with the boom in data, both government and industry have pioneered exciting new analytic tools to systematically collect, harvest, mine, and examine data to uncover hidden insights, patterns, correlations, trends, and “intelligence.” Much of the exciting new technology and analysis can be employed to tackle trade transparency.

For example, data warehousing and retrieval are enhanced by cutting-edge technologies that search, mine, analyze, link, and detect anomalies, suspicious behaviors, and related or interconnected activities and people. Unstructured data sources can be automated, scanned, and aggregated. Fraud frameworks can be deployed to help concerned government and commercial entities detect suspicious activity and anomalies using scoring engines that can rate, with high degrees of statistical accuracy, behaviors that warrant further investigation while generating alerts when something of importance changes. Text analytics can work with both structured and free-form text and identify numbers, words, and specific form fields. Predictive analytics use elements involved in a successful case or investigation and overlay these elements on other datasets to detect previously unknown behaviors or activities, enhancing and expanding an investigator's knowledge, efforts, and productivity while more effectively deploying resources. Social network analytics help analysts and investigators detect and prevent suspect activity by going beyond individual transactions to analyze all related activities in various media and networks, uncovering previously unknown relationships. Visual analytics is a high-performance, in-memory solution for exploring massive amounts of data very quickly. It enables users to spot patterns, identify opportunities for further analysis, and convey visual results via online reports or the iPad.25

We have already seen that classifying and monitoring trade and associated international travel, finance, shipping, logistics, insurance data, and more generates tremendous information that can be applied to promote trade transparency. For example, web analytics and web crawling alone can search shipping companies and customs websites to review shipment details and compare them against their corresponding documentation. Advanced analytics can also be deployed to develop unit price analysis, unit weight analysis, shipment and route analysis, international trade and country profile analysis, and relationship analysis of trade partners and ports.26

Of course, there has also been a proliferation of classified data that could be better exploited to examine certain questionable aspects of trade.

I am technology challenged, but it appears to me that we have barely scratched the surface in applying analytics to the data that are currently available and could be made available. Discounting the unattainable, by using modern analytic tools to exploit a variety of relevant big data sets, I believe international trade transparency is theoretically achievable or certainly possible at a factor many times over what we have today.

Case Example: Operation Deluge

In 2006, the U.S. and Brazilian TTUs collaborated in Operation Deluge. The TTUs jointly targeted a scheme that had undervalued U.S. exports to Brazil to evade more than $200 million in Brazilian customs duties between 2001 and 2006.27 In a huge bust, 950 Brazilian federal police officers and 350 customs agents executed search warrants at 238 locations in various Brazilian states.28 They also executed 128 arrest warrants that netted both government officials and the directors and owners of several large Brazilian companies. Nine of the detainees were employees of Brazil's Internal Revenue Service.29 During the joint operation, U.S. ICE agents in Miami seized approximately $500,000 in goods slated for export to Brazil.30

The United States and Brazil accused the defendants of tax evasion, document fraud, public corruption, and the undervaluation of exports. The commodities included an assortment of goods including electronics and telecommunications equipment, orthopedic equipment, surgical gloves, fruits, plastic bottles, garments and textiles, batteries, vehicles, dietary supplements, and perfumes.31

According to Brazilian authorities, the leader of the ring was Marco Antonio Mansur. Mansur was arrested with his son—a co-conspirator—in their apartment in an upscale neighborhood of Sao Paulo. Mansur was a wealthy businessman who once lived in Paraguay.32 Police accused him of creating dozens of front companies to carry out his undervaluation scheme; the companies were registered in Uruguay, Panama, the British Virgin Islands, and Delaware.33