Chapter 3

Black Market Peso Exchange

Colombia's Black Market Peso Exchange (BMPE) is an example of a regional black market financial system based on the misuse of international trade. Its original purpose was to obtain restricted hard currency (U.S. dollars) so Colombian businessmen could import goods (primarily from the United States) for resale and offer them at very competitive prices. Over the years, there were disastrous consequences. Inside Colombia, the BMPE harmed Colombian businesses that played by the rules. The BMPE facilitated trading inefficiencies and inequalities; it also circumvented needed revenue streams for the government. And with the expansion of the Colombian-based drug cartels, the BMPE became a key technique to launder staggering amounts of drug money. Today, the BMPE is one of the largest money laundering methodologies in the United States. And BMPE-like systems are found in various areas around the world.

The BMPE is an example of what is sometimes called an informal value transfer system. Other labels include informal banking, underground banking, parallel banking, and some are known as alternative remittance systems. Occasionally, these regional underground financial schemes are simply lumped together and erroneously labeled hawala. (hawala is explained in Chapter 4.)

The above financial systems—and others like them—are regional and ethnic based. I want to emphasize that I am not using “ethnic” in a pejorative sense. On the contrary, the systems are highly developed, sophisticated, and generally very efficient. Many have existed for hundreds of years—long before the advent of modern “Western” banking. Today they are often used by various immigrant groups as a low-cost, indigenous alternative to modern banking.

Many of the underground financial systems such as the BMPE, fei-chien, and hawala operate in a manner where the goods move and the money remains in place. Moreover, the importance of these systems as they relate to this book is that they all have a common denominator (i.e., historically and culturally they all use trade as a method of transferring value or balancing the books between brokers). This process of countervaluation will be described in Chapter 4.

Although the BMPE is not generally considered an alternative remittance system used by immigrants (such as hawala), it is based on the misuse of trade goods. Similar systems are found elsewhere, so familiarization with the scheme is essential to understanding TBML.

Background of the BMPE

The BMPE originated in Colombia years before the drug cartels appropriated it for their purposes. Similar to other money laundering methodologies, tax and tariff avoidance and exchange rate restrictions were the catalysts for an informal value transfer system that evolved into a very effective scheme to wash illicit funds.

Beginning in 1967, Colombia enacted regulations that strictly prohibited citizens' access to foreign exchange. Merchants who wanted to import U.S. trade goods through legitimate banking channels had to pay stiff surcharges above the official exchange rate. The Colombian peso was not free-floating. The government restrictions forced Colombian importers to utilize government-licensed institutions to obtain financing based on the peso. In addition to reporting the details of these transactions to the Ministry of Finance, the banks involved also charged stiff premiums for their services on top of the government's sales taxes and other fees. To avoid these steep add-on costs, importers often turned to underground peso brokers, from whom they could buy U.S. dollars on the black market for less than the official exchange rate to finance their trade, all the while sidestepping government oversight.2

By the 1980s, the underground peso situation was taking on a new dimension. As U.S. cities found themselves awash in Colombian cocaine, narco-traffickers and cartels were faced with a logistical problem—namely, how to launder and repatriate the tons of U.S. currency they had accumulated in North America as a result of drug sales. Meanwhile, black market peso dealers needed more and more U.S. dollars to sell to Colombian importers for the purchase of consumer goods, electronics, cigarettes, whiskey, machinery, gold, and so forth. Supply met demand in the form of the BMPE.3

By 2004, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) declared that the BMPE was responsible for laundering nearly $5 billion worth of drug money annually.4 Although recent efforts to control the BMPE by the Colombian and U.S. governments have been somewhat successful, the money laundering methodology still exists between the two countries. An official Colombian estimate is that approximately 45 percent of the country's imported consumer goods are facilitated via the BMPE.5

A Typical BMPE Value Transfer Scheme

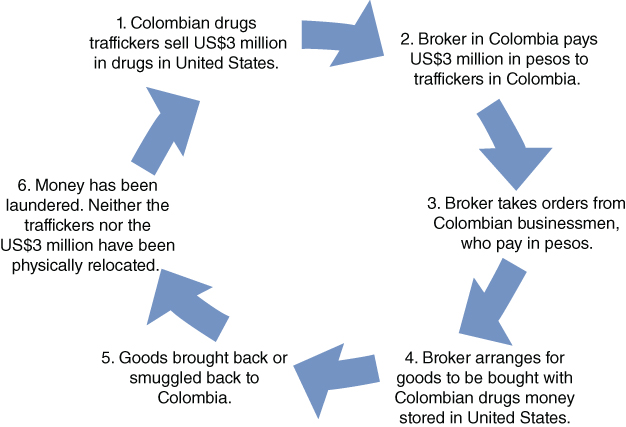

The BMPE cycle begins with drug sales. For example, consider a Colombian drug cartel that has sold $3 million of cocaine in the United States. A representative of the cartel sells these accumulated dollars to a Colombian peso broker at a large discount. In the cartel's view, this discount is an acceptable price of doing business and the cost of laundering its illicit proceeds.

Despite being sold to a Colombian broker, the actual U.S. dollars remain in the United States, where the broker will shortly make use of them. In the meantime, the broker pays the cartel with the $3 million (less fees) worth of clean Colombian pesos, which he has previously purchased at a discount from Colombian businesses that participate in the BMPE. The cartel is now out of the picture, having successfully sold its drug dollars in the United States and having obtained pesos in return.

To complete the BMPE cycle, the peso broker must take two more steps. First, he directs his representatives in the United States to place the purchased drug dollars into U.S. financial institutions, using a variety of techniques designed to avoid arousing suspicion or triggering the financial intelligence reporting (see Figure 3.1 and box, “How Peso Exchangers Place Dollars into the U.S. Financial System”). Second, he takes orders from Colombian businesses for U.S. trade goods, arranging for their purchase using the laundered drug money he owns in the United States. American manufacturers and distributors, knowingly or unknowingly, accept payment in drug dollars and export these goods to Colombia. The broker has now laundered the $3 million in drug money he purchased from the drug cartel. Moreover, the new pesos he receives from the Colombian businesses will allow him to conduct future transactions with the cartels.

Figure 3.1 The BMPE cycle6

Source: Cassara and Jorisch, On the Trail of Terror Finance, p. 81.

Each part of the BMPE process moves the money one more step away from narcotics. This sometimes makes it difficult for law enforcement to establish criminal knowledge and intent at later stages of the process.

Although foreign narcotics cartels, organized crime, and overseas businesses are the main players in the BMPE, U.S. companies must take some responsibility for the problem. Unquestioning corporate acceptance of orders for trade goods from questionable sources is a form of willful blindness. For example, in 1997, a Colombian businesswoman cooperated with federal agents and—in disguise—testified before Congress. She stated, “As a money broker, I arranged payments to many large U.S. and international companies on behalf of Colombian importers. These companies were paid with U.S. currency generated by narcotics trafficking. They may not have been aware of the source of the money. However, they accepted payments from me without ever questioning who I was, or the source of the money.”7

In an undercover pickup operation in the Miami area run by the Tri-County Task Force that culminated in 2011, tens of millions of drug-tainted dollars were laundered in a BMPE scheme centered on computer stores, cell phone outlets, and electronic game distributors. The scheme operated for a number of years and moved drug money out of the United States and into Mexico, Colombia, and other drug-producing countries via trade. The owners of the businesses turned a collective blind eye and professed no knowledge of the narco-money link. “It defies logic and credibility,” said Donald Semesky, a former IRS criminal agent with knowledge of the operation. “They don't want to know where the money came from. What they are saying is, ‘I didn't see the drugs. Why should I not be able to sell my wares?’”8

This attitude and method of business has direct impact on compliance officers in financial institutions and demonstrates the importance of knowing your customer. See Chapter 10 for red-flag indicators.

Of course, in the Colombian BMPE, it is not just the proceeds of drugs that get laundered but also illicit funds from corruption, weapons trafficking, prostitution, illegal gold mining, and other illegal activities. And the infusion of so much illegal money into Colombia's 2013 $330 billion economy can inflate economic growth numbers by several basis points. According to Luis Edmundo Suarez, head of Colombia's financial intelligence unit (FIU)—the UIAF, “It creates suffering, distorts the economy and alters reference prices.”9 National tax agency head Juan Ortega and some economists feel that the laundered proceeds due to TBML's fake or overstated sales distort a range of official data from inflation to exports and imports. Erroneous data have a ripple effect on everything from government budgets to social programs. Moreover, in Colombia often times the laundered goods are sold at below-market prices. According to Ortega, “For a poor country, the social impact [of unfair competition] is brutal.” “It limits growth and destroys opportunity for legitimate business.”10

According to experienced BMPE industry workers in Colombia, evasion of customs charges is frequently facilitated by the complicity of corrupt customs authorities.11 In Colombia—as well as other countries struggling with forms of TBML—the pernicious effects of corruption not only enable TBML but also cost the government much-needed revenue and exacerbate social and cultural ethics and values.

Expansion of the BMPE to Mexico and Venezuela

Today—decades after the BMPE was established, and despite the lifting of many of the above-described official Colombian currency controls—narco-traffickers continue to avail themselves of the same underground system, as do many legitimate businesses. In Mexico, Venezuela, and other Latin American countries, organized crime has learned to read from the same BMPE playbook. For example, in June 2010, the Mexican government announced regulations limiting deposits of U.S. cash into Mexican banks.12 (Subsequently, in June 2014 the government revised the U.S. dollar restrictions so as to ease the impact on legitimate businesses. The impact of the revision is to be determined.)13 The regulations were later expanded to include purchases of large-ticket goods such as expensive cars, jewelry, and homes, as well as cash deposits made at exchange houses (casas de cambio) and brokerages (casas de bolsa). The restrictions were put in place primarily to combat the smuggling of illicit bulk cash into Mexico. Yet following the rule of unattended consequences, using variations of the BMPE, narco-trafficking organizations in Mexico have been able to skirt Mexican government limits on the use of how much money Mexicans can deposit.

A number of law-enforcement cases have shed light on the ways the BMPE has been adapted by Mexican narcotics-trafficking organizations. One of the first investigations focusing on TBML between Mexico and the U.S. centered on Blanca Cazares, the alleged queen of money laundering for the Sinaloa cartel. She was indicted in 2008 in Los Angeles for “processing illicit proceeds.” One of her techniques was to use the illicit funds from U.S. narcotics sales to import textiles from Asia into the Los Angeles area and then export them to Mexico.14 The U.S. Department of the Treasury's Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) designated Cazares and 19 companies and 22 individuals in Mexico that were part of her financial network as specially designated narcotics traffickers subject to economic sanctions pursuant to the Foreign Narcotics Kingpin Designation Act.15

In 2014, Operation Fashion Police rocked the Los Angeles garment district. A Los Angeles–based maternity clothes wholesaler allegedly received drug proceeds. In the manner described in the BMPE cycle, the dirty dollars were used to pay for product from other nearby garment shops for export orders to Mexico.

One of the clothing exporters allegedly mixed customs fraud into the BMPE conspiracy. “Made in China” labels were removed from thousands of imported garments. (The ruse was very similar to an investigation I worked in the Middle East in the 1990s, described in Chapter 2.) In the Los Angeles case, one of the suspects was paid 50 to 75 cents for each of the altered garments. The fraud saved the co-conspirators from paying taxes on the “Made in China” imports because on paper they appeared to be “American-made,” and exempt from customs duties under the North American Free Trade Act (NAFTA).17

More than $90 million was seized. It was the biggest one-day seizure of cash in the United States.18 The large cash seizure demonstrated that the Mexican cartels had successfully adapted the Colombian BMPE methodology in such a way that bulk cash did not have to be smuggled into Mexico. The bulk cash—proceeds from narcotics trafficking, kidnapping, stolen cars, and other illegal activities—stays on the U.S. side of the border.

The collapse of the Venezuelan bolívar under the policies of former President Hugo Chavez and his successors has been striking. Since he took office 1999, the official cost of the dollar in bolívars has risen more than tenfold.19 And there is a striking imbalance between the official rate and the value of the dollar on the prolific Venezuelan black market. The black market rate factors in supply, demand, and inflation. The centralized government tries to hide both the weak currency and the endemic corruption by setting a fixed, artificial rate. Moreover, price and foreign exchange controls have proven to be a catalyst for corruption—the great facilitator of international money laundering.

In 2003, the government tried to stem capital flight by imposing stringent exchange controls. Ordinary Venezuelan citizens and businesses have faced limits on the amount of foreign currency they can acquire at the heavily subsidized official rate. These restrictions have contributed to depressed economic activity and shortages of consumer goods. To meet the rest of their foreign currency needs, many Venezuelans turned to the black market, where the bolívar has traded at a fraction of its official value.

The Venezuelan government responded to sharp declines in the price of the bolívar on the black market with a series of incremental official devaluations and ever-tighter controls. The adjustments made life slightly easier for the country's beleaguered exporters but did not assist importers or consumers, including those wishing to import popular U.S. goods. As a result, many consumer items practically disappeared from marketplaces. As the Venezuelan central bank became stingier in doling out dollars at the official rate, demand for greenbacks grew on the black market.

Overlapping Venezuela's serious economic downturn was a commensurate upturn in criminality, including narcotics trafficking and money laundering. According to the 2014 congressionally mandated International Narcotics Control Strategy Report (INCSR) Volume II on Money Laundering prepared by the U.S. State Department, Venezuela is a country of “primary concern.” The introduction to the Venezuela report notes the following: “Trade-based money laundering remains a prominent method for laundering regional narcotics proceeds. Converting narcotics-generated dollars into Venezuelan bolivars and then back into dollars is no longer attractive for money-laundering purposes given Venezuela's rampant inflation (approximately 50 percent in 2013) and the current bureaucratic challenges for converting bolivars into dollars.”22

The State Department also reports that some black market traders ship their goods through Venezuela's Margarita Island free port, one of three free trade zones/ports in the country. However, the use of free trade zones for TBML has become less attractive in recent years because the margins gained by laundering money through the government's currency control regime have reduced the incentive to use a free trade zone to avoid import duties.23

For example, there are reports that dozens of Venezuelan companies have conspired with Ecuadorian firms to carry out multimillion-dollar operations involving fictitious exports and phantom companies (as well as using bank accounts in Panama, the Bahamas, and Anguilla). The Venezuelan businesses involved made transfers to Ecuador in exchange for fake exports to Venezuela. Many of the cases concerned Venezuelan state contractors involved in construction or importing food. This gave them the justification needed to access dollars at preferential rates via Venezuela's Center for Foreign Trade, also known as Cencoex. Some payments were made in advance, before the merchandise even arrived in Venezuela; there were also Ecuadorian exports with inflated values; multiple invoices for the same shipments; and fictitious shipments of products that never actually made it to Venezuela.24

The malfunctioning currency system is the catalyst for various schemes used by importers to overinvoice the value of goods shipped into the country in order to obtain dollars provided by the government at artificially low prices. At times, the imports only occur on paper. The suspect importers pocket the fraudulently obtained dollars, bribe officials, and/or sell the scarce dollars for huge profits in the country's black market.

In just a few examples of wildly inflated invoices in Venezuela,26 weed whackers were imported at $12,300 each. Machinery was imported to kill and gut chickens. The invoice price was $1.8 million. Subsequent investigation disclosed the machinery was a heap of rusted scrap metal. A device was imported to remove kernels from ears of corn. The invoiced price presented to Venezuelan authorities was $477,750. The actual price was about $2,900.

Thus, international businesses (including in the United States) are approached by Venezuela black market currency brokers and their fronts with offers for the purchases of goods in demand in Venezuela. The money-laundering techniques involved are almost identical to those described in Chapter 2 and above, dealing with the Colombian and Mexican BMPE. Unfortunately, some businesses complete the transactions. They knowingly or unknowingly accept cash and other payments that are often comingled with illicit proceeds or are involved with various types of fraud. And despite the warning signs, financial institutions are often the intermediaries.

The China Connection

When U.S. government authorities became aware of the BMPE in the mid-1990s, the methodological model was Colombian peso brokers purchasing U.S. manufactured goods using laundered drug proceeds. This still occurs. But investigators have also found that similar black market exchange “shopping centers” are increasingly active in other countries. And there are signs that Chinese manufactured goods are becoming favored instruments in the BMPE and BMPE-like financial systems.

For example, between 2000 and 2008, bilateral trade between China and Mexico grew from less than $1 billion to approximately $18 billion.28 Although the exponential growth of legitimate Chinese trade has occurred in many areas of the world, there is some evidence that Mexican drug trafficking organizations using illicit proceeds are buying container loads of cheaply made Chinese goods. Using the technique of overinvoicing explained in Chapter 2, low-quality Chinese manufactured items are made to appear on paper as being worth significantly more. By means of the legitimate international financial system, Chinese goods are purchased in Mexico, the United States, Europe, Dubai, the Colon Free Trade Zone, Africa (see Chapter 5), and elsewhere. The purchase launders the illicit proceeds.

There is anecdotal evidence that sometimes cheaply manufactured Chinese goods are never actually claimed after arrival in the importing country.29 The purchase of the goods serves to launder the drug money. For professional money launderers, that is the price of doing business. Sometimes the end result is that the Chinese products in the unclaimed shipping containers eventually find their way onto the local economy's black market. There are also reports that small Chinese banks are involved with processing enormous numbers of payments for Mexico for trade goods that may or may not actually exist to facilitate the laundering of drug proceeds.30

Cheat Sheet

- The BMPE is an example of an informal value transfer system. It is also sometimes categorized as parallel banking or underground banking.

- The BMPE is a form of TBML and is one of the largest money laundering methodologies in the Western Hemisphere.

- Similar to other trade-based value transfer systems, it operates by transferring money without moving money.

- The BMPE originated in Colombia long before the proliferation of narcotics trafficking. The black market system was developed in order for Colombian businessmen to obtain access to scarce dollars.

- In the BMPE, a black market peso broker buys narcotics proceeds (generally in the United States) at a discount from a narcotics trafficking organization. Using a variety of techniques, the broker then arranges for the cash to be deposited, structured, or placed into financial institutions or money services businesses. The money is used to buy a variety of trade goods that are then exported to Colombia and other Latin American countries.

- The BMPE has expanded and is now frequently found in Mexico and Venezuela.

- In addition to the United States, trade goods used in the BMPE are often purchased from China, Europe, and other suppliers.

- Similar systems to the BMPE are found throughout the world.